Professional Documents

Culture Documents

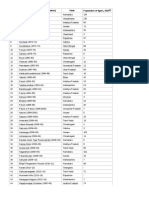

Oyce Acobs: Selected Bibliography G 1959 - D / J 1999

Uploaded by

boban.ilicgmx.atOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oyce Acobs: Selected Bibliography G 1959 - D / J 1999

Uploaded by

boban.ilicgmx.atCopyright:

Available Formats

Iconography of Deities and Demons: Electronic Pre-Publication 1/2

Last Revision: 20 November 2006

Mithra The Persians certainly did conceive of

their gods in anthropomorphic form (BOYCE

Iranian god, →DDD. Mithra is an 1982a: 179; comprehensively JACOBS 2001:

ancient Aryan deity first documented with 84-86). Although no Persian cult images

the Indo-Aryans dispersal into Anatolia in (agalmata) were known to Herodotus

connection with the “Aryan migrations” (Historiae 1.131), they might well have

(Mitanni contract of Shuppiluliuma I [c. existed (see GARRISON 2000: 143 with n.

1335-1320]: Mi-it-ra-). The god is also 64). We cannot therefore exclude a priori

mentioned in the Veda (Mitrá-); the Avesta the possibility of a pictorial representation

(Miṯra-), where a single Yašt (no. 10) is of pre-Hellenistic M. However, while there

dedicated to him; and in OP inscriptions can be no doubt about M.’s relative

(Miṯ/tra-) (MAYRHOFER 1978). The wide importance in Iranian religion since the 2nd

diffusion of theophoric names compounded mill. and a particular development of the

with M. in pre-Achaemenid and Achae- god toward solar qualities during the late

menid times west of the central Iranian salt Achaemenid period, pictorial representa-

deserts (MAYRHOFER 1973: 8.1138-8.1150, tions of the god predating the Hellenistic

8.1167-8.1169; SCHMITT 1978: 395-455, period have not yet been identified as such

esp. 415-426; ZADOK 2002: 129) leaves no in Western Asia. Tentative identifications of

doubt that M. was venerated in Persia long the four-winged divine being (→Auramaz-

before the 4th cent., when the god is first da) as M. (e.g., UEHLINGER 1999: 178) can

mentioned in Achaemenid royal inscriptions hardly be substantiated, nor do later

from the reign of Artaxerxes II (404-359; representations of M. such as those

KENT 1950: 154f A2Sa 4f; A2Sd 4; A2Ha 5f; preserved in Roman mithraea (cf. JACOBS

A2Hb) and Artaxerxes III (358-338; KENT 1999 with extensive referencing) provide

1950: 156 A3Pa 25). any clues as to how M. was conceived in the

Basing themselves mainly on the Achaemenid and earlier periods.

references to M., as well as to →Anahita, in

Selected Bibliography

the Achaemenid inscriptions, scholars have GERSHEVITCH 1959 • DRIJVERS /DE JONG 1999

speculated about radical changes in

religious politics during the time of Bruno Jacobs

Artaxerxes II. Those changes have been

associated either with a cultic reorientation

initiated by the king within the Achaemenid

royal house (BOYCE 1982a: 1004), or a

“pagan counter-revolution,” rooted in pre-

Zoroastrian concepts, against the mono-

theistic tendencies of Zoroastrianism (thus,

e.g., HINZ 1961: 160f; cf. GERSHEVITCH

1959: 19f; MALANDRA 1983: 4, 24f). These

hypotheses rest, however, on highly

problematic assumptions regarding the

aniconic and/or monotheistic nature of

Persian religion prior to Artaxerxes II (cf.

→Anahita). The mention of M. in late

Achaemenid royal inscriptions merely

testifies to his relatively important position

in the Persian pantheon (cf. also Duris of

Samos, ap. Athen. X 45, 434 e-f; Strabo,

Geographia XI 14, 9), and to the preference

for this god on the part of those kings in

whose inscriptions he is mentioned.

In the course of the Achaemenid period

M. became increasingly associated with the

sun god (→Solar deities), with whom he

was finally identified (Strabo, Geographia

XV 3, 13; Curtius Rufus, Historiae

Alexandri Magni Macedonis IV 13, 12;

Plutrach, Vita Artaxerxis 30, 7-8; JACOBS

1991: 55-57; on the disputed mention of M.

in Herodotus, Historiae 1.131 cf.

NAGEL/JACOBS 1984: 369f; EDWARDS

1990; CORSTEN 1991).

IDD website: http://www.religionswissenschaft.unizh.ch/idd

Iconography of Deities and Demons: Electronic Pre-Publication 2/2

Last Revision: 20 November 2006

Bibliography

BOYCE M., 1982a, Art. Anāhīd. I. Ardwīsūr Anāhīd, in: YARSHATER E., ed., Encyclopaedia Iranica, London, 1:1003-1005.

CORSTEN Th., 1991, Herodot I-131 und die Einführung des Anahita-Kultes in Lydien: IrAnt 26,163-180.

DDD = VAN DER TOORN K./BECKING B./VAN DER HORST P.W., eds., 21999, Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Bible,

Leiden/Bosten/Köln.

DRIJVERS H.J.W./DE JONG A.F., 1995, Art. Mithras, in: DDD, 1083-1089.

EDWARDS M. J., 1990, Herodotus and Mithras: Histories I.131: AJPh 111,1-4.

GARRISON M.B., 2000, Achaemenid Iconography as Evidenced by Glyptic Art: Subject Matter, Social Function, Audience and

Diffusion, in: UEHLINGER C., ed., Images as Mass Media. Sources for the Cultural History of the Near East and the Eastern

Mediterranean (Ist Millennium BCE) (OBO 175), Fribourg Switzerland/Göttingen, 115-163.

GERSHEVITCH I., 1959, The Avestan Hymn to Mithra, Cambridge.

HINZ W., 1961, Zarathustra, Stuttgart.

JACOBS B., 1999, Die Herkunft und Entstehung der römischen Mithrasmysterien. Überlegungen zur Rolle des Stifters und zu den

astronomischen Hintergründen der Kultlegende (Xenia 43), Konstanz.

— 2001, Kultbilder und Gottesvorstellung bei den Persern. Zu Herodot, Historiae 1.131 und Clemens Alexandrinus,

Protrepticus 5.65.3, in: Bakır T. et al., eds., Achaemenid Anatolia. Proceedings of the First International Symposium on

Anatolia in the Achaemenid Period, Bandırma 15-18 August 1997 (PIHANS 92), Leiden, 83-90.

KENT R.G., 1950, Old Persian. Grammar, Texts, Lexicon (AOS 33), New Haven, CT.

LECOQ P., 1997, Les inscriptions de la Perse achéménide. Traduit du vieux perse, de l’élamite, du babylonien et de l’araméen, Paris.

MALANDRA W.W., 1983, An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion. Readings from the Avesta and the Achaemenid Inscriptions

(Minnesota Publications in Humanities 2), Minneapolis, MN.

MAYRHOFER M., 1973, Onomastica Persepolitana. Das altiranische Namengut der Persepolis-Täfelchen (Veröffentlichung der

Iranischen Kommission 1; Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse.

Sitzungsberichte 286), Wien.

— 1978, Die bisher vorgeschlagenen Etymologien und die ältesten Bezeugungen des Mithra-Namens: AcIr 17,317-325.

NAGEL W./JACOBS B., 1984, Königsgötter und Sonnengottheit bei altiranischen Dynastien: IrAnt 29,337-391.

SCHMITT R., 1978, Die theophoren Eigennamen mit altiranisch MIΘRA-: AcIr 17,395-455.

UEHLINGER CH., 1999, ‘Powerful Persianisms’ in Glyptic Iconography of Persian Period Palestine, in: BECKING B./KORPEL M., eds.,

The Crisis of Israelite Religion, Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-exilic Times (Oudtestamentische

Studien 42), Leiden/Boston/Köln, 134-180.

ZADOK R., 2002, The Ethno-Linguistic Character of Northwestern Iran and Kurdistan in the Neo-Assyrian Period: Iran 40,89-151.

IDD website: http://www.religionswissenschaft.unizh.ch/idd

You might also like

- Egyptian Civilization Its Sumerian Origin and Real ChronologyFrom EverandEgyptian Civilization Its Sumerian Origin and Real ChronologyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- E Idd AnahitaDocument3 pagesE Idd AnahitaHolbenilordNo ratings yet

- 'Archaic Greece and The Veda' by N. KazanasDocument27 pages'Archaic Greece and The Veda' by N. KazanasSrini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- 86.henkelman - Pantheon and Practice of WorshipDocument39 pages86.henkelman - Pantheon and Practice of WorshipAmir Ardalan EmamiNo ratings yet

- 2aryan Pandavas 08589173-Asko-Parpola-Pandaih-and-Sita-On-the-Historical-Background-on-the-Sanskrit-Epics PDFDocument9 pages2aryan Pandavas 08589173-Asko-Parpola-Pandaih-and-Sita-On-the-Historical-Background-on-the-Sanskrit-Epics PDFsergio_hofmann9837No ratings yet

- Arimaspians and Cyclopes The Mythos ofDocument55 pagesArimaspians and Cyclopes The Mythos ofGosciwit MalinowskiNo ratings yet

- Aphrodite Ourania of the Bosporus: The Great Goddess of a Frontier PantheonDocument19 pagesAphrodite Ourania of the Bosporus: The Great Goddess of a Frontier PantheonbenjoliciousNo ratings yet

- Indic Ideas in The Graeco-Roman World, by Subhash KakDocument14 pagesIndic Ideas in The Graeco-Roman World, by Subhash KakCaitra13No ratings yet

- Akhenaten Surya and Rgveda Article by Subhash Kak PDFDocument34 pagesAkhenaten Surya and Rgveda Article by Subhash Kak PDFsoulsplashNo ratings yet

- Proto Paris and Proto Achilles ... 1Document3 pagesProto Paris and Proto Achilles ... 1Stavros GirgenisNo ratings yet

- From Lunar Nodes To Eclipse Dragons TheDocument30 pagesFrom Lunar Nodes To Eclipse Dragons ThecamilaNo ratings yet

- The Achaemenid Kings and The Worship of Ahura Mazda - Proto-ZoroasDocument8 pagesThe Achaemenid Kings and The Worship of Ahura Mazda - Proto-Zoroasinvince2No ratings yet

- Egyptian Concepts and Practices in the Old TestamentDocument15 pagesEgyptian Concepts and Practices in the Old TestamentOrockjoNo ratings yet

- Mithra in Roman OrientDocument19 pagesMithra in Roman OrientIsrael CamposNo ratings yet

- Yehoshua Frenkel The Turks of The EurasiDocument35 pagesYehoshua Frenkel The Turks of The EurasiAtif BeigNo ratings yet

- Greek Buddhism Early Religious ContactsDocument52 pagesGreek Buddhism Early Religious ContactsFriedrich NitschieNo ratings yet

- Introduction To World LiteratureDocument6 pagesIntroduction To World LiteratureMyk PagsanjanNo ratings yet

- DOCUMENT A brief note on the circumcised Odomantes in Aristophanes' comedyDocument4 pagesDOCUMENT A brief note on the circumcised Odomantes in Aristophanes' comedyStefan StaretuNo ratings yet

- Rigveda Timeline DebateDocument23 pagesRigveda Timeline Debatekumbla_maheshNo ratings yet

- Bhandarkar Oriental Research InstituteDocument29 pagesBhandarkar Oriental Research InstituteCecilie RamazanovaNo ratings yet

- Haldi and Mithra Mher PDFDocument11 pagesHaldi and Mithra Mher PDFAlireza EsfandiarNo ratings yet

- The Micro and Macro Worlds 2Document19 pagesThe Micro and Macro Worlds 2udayNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian OnomasticsDocument11 pagesAncient Egyptian Onomasticsboschdvd8122100% (3)

- Hancock Parmer Central Asia Before Russian Dominion 2022Document13 pagesHancock Parmer Central Asia Before Russian Dominion 2022Reem ZeyadNo ratings yet

- Mithraism A Religion For The Ancient MedesDocument19 pagesMithraism A Religion For The Ancient MedesAnitaVasilkova100% (1)

- Proceedings of The 3rd EC of Iranian StudiesDocument7 pagesProceedings of The 3rd EC of Iranian StudiesDonna HallNo ratings yet

- El's Abode - Mythological Traditions Related To Mount Hermon and To The Mountains of Armenia by Edward LipinskiDocument58 pagesEl's Abode - Mythological Traditions Related To Mount Hermon and To The Mountains of Armenia by Edward LipinskiSheni Ogunmola100% (1)

- Assyrians or Arameans JM FieyDocument13 pagesAssyrians or Arameans JM FieyZakka LabibNo ratings yet

- HTTP://WWW Scribd com/doc/79678937/Vedic-PhysicsDocument34 pagesHTTP://WWW Scribd com/doc/79678937/Vedic-PhysicsSinanvMangadNo ratings yet

- A Hypothesis About Some So Called PosthuDocument5 pagesA Hypothesis About Some So Called PosthuHabid KhanNo ratings yet

- Mycenaean Thrace A Theme To Be ContinuedDocument13 pagesMycenaean Thrace A Theme To Be ContinuedIvaylo KaradzhinovNo ratings yet

- Eastern Asia Minor and The Caucasus in Ancient MythologiesDocument24 pagesEastern Asia Minor and The Caucasus in Ancient MythologiesRobert G. Bedrosian100% (1)

- Rosicrucian Digest 2007Document60 pagesRosicrucian Digest 2007mprussoNo ratings yet

- PALAIMA Ilios Tros & TlosDocument12 pagesPALAIMA Ilios Tros & Tlosmegasthenis1No ratings yet

- The Planetary Deities in Buddhist FuneraDocument19 pagesThe Planetary Deities in Buddhist FuneraShim JaekwanNo ratings yet

- The Eponymous Officials of Greek Cities: I (R. Sherk)Document42 pagesThe Eponymous Officials of Greek Cities: I (R. Sherk)ΕΣΤΙΤΙΣΣΙΩΝΤΙΣΙΣNo ratings yet

- ALPHABETS - OtDocument19 pagesALPHABETS - OtRavindran GanapathiNo ratings yet

- Cultural Choices and Political Identities in Second Century Portrait StatuesDocument51 pagesCultural Choices and Political Identities in Second Century Portrait StatuesMilos HajdukovicNo ratings yet

- The Debated Historicity of Hezekiah's Reform in The Light of Historical and Archaeological ResearchDocument18 pagesThe Debated Historicity of Hezekiah's Reform in The Light of Historical and Archaeological ResearchWilian CardosoNo ratings yet

- Kushite IndiansDocument832 pagesKushite IndiansAsarNo ratings yet

- Annus, Amar (2012) - Descent Into The Netherworld HellDocument3 pagesAnnus, Amar (2012) - Descent Into The Netherworld HellKay BarnesNo ratings yet

- Achaemenid Kings and The Cult of AMazdaDocument7 pagesAchaemenid Kings and The Cult of AMazdaIsrael CamposNo ratings yet

- Anthony_Brown_2017_The dogs of war a Bronze Age initiationDocument15 pagesAnthony_Brown_2017_The dogs of war a Bronze Age initiationdaniyal.zhanabayevNo ratings yet

- Valeria Fol - Rock-Cut MonumentsDocument10 pagesValeria Fol - Rock-Cut MonumentsAdriano PiantellaNo ratings yet

- Hesiod Theogony and Works and DaysDocument19 pagesHesiod Theogony and Works and DaysPhil Suarez50% (6)

- Ancient Egyptian Women Held Priestly RolesDocument24 pagesAncient Egyptian Women Held Priestly RolesNourhanMagdyNo ratings yet

- Abgar Legend: Text and Iconography Part IDocument76 pagesAbgar Legend: Text and Iconography Part ILoznjakovic NebojsaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To World LiteratureDocument6 pagesIntroduction To World LiteratureMyk PagsanjanNo ratings yet

- Kernos 772Document18 pagesKernos 772vladan stojiljkovicNo ratings yet

- TammuzDocument1 pageTammuzErimar CruzNo ratings yet

- Comparative Notes On Hurro-Urartian, Northern Caucasian and Indo-EuropeanDocument116 pagesComparative Notes On Hurro-Urartian, Northern Caucasian and Indo-Europeanfcrevatin100% (1)

- Jasink Marino - The West Anatolian Origins of The Que Kingdom DynastyDocument20 pagesJasink Marino - The West Anatolian Origins of The Que Kingdom DynastyjohnkalespiNo ratings yet

- Literature: The Truth in LiteratureDocument3 pagesLiterature: The Truth in LiteraturePrecious Amethyst BelloNo ratings yet

- A "Hyksos Connection" Thoughts On The Date of Dispatch of Some of The Middle Kingdom Objects Found in The Northern LevantDocument21 pagesA "Hyksos Connection" Thoughts On The Date of Dispatch of Some of The Middle Kingdom Objects Found in The Northern LevantSongNo ratings yet

- Astronomical Date of The Early Bronze Beginning in The Biblical Creation and Cain-Abel StoriesDocument3 pagesAstronomical Date of The Early Bronze Beginning in The Biblical Creation and Cain-Abel StoriesborimoriNo ratings yet

- The Rose in Ancient Greek CultureDocument83 pagesThe Rose in Ancient Greek CulturekfrydasNo ratings yet

- Project Muse 26954-987877Document21 pagesProject Muse 26954-987877Ramdane Ait YahiaNo ratings yet

- Greek Mythology OriginsDocument15 pagesGreek Mythology OriginsJean Ng100% (1)

- The Alexiad - An Insight into the Life and Reign of Emperor Alexius IDocument11 pagesThe Alexiad - An Insight into the Life and Reign of Emperor Alexius Iboban.ilicgmx.atNo ratings yet

- Discover the world's books through Google Book SearchDocument634 pagesDiscover the world's books through Google Book Searchboban.ilicgmx.atNo ratings yet

- PSB 14 Eusebiu de Cezareea II Viata SF ConstantinDocument295 pagesPSB 14 Eusebiu de Cezareea II Viata SF ConstantinGheorgheNo ratings yet

- Google Book Search ProjectDocument955 pagesGoogle Book Search Projectboban.ilicgmx.atNo ratings yet

- Google Book Search ProjectDocument955 pagesGoogle Book Search Projectboban.ilicgmx.atNo ratings yet

- Si No. Tiger Reserve (Year of Creation) State Population of Tigers, 2014Document2 pagesSi No. Tiger Reserve (Year of Creation) State Population of Tigers, 2014shrekNo ratings yet

- Vol 8 Issue 2 - May 23-29, 2015Document32 pagesVol 8 Issue 2 - May 23-29, 2015Thesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- Chart of The Three Modes (Gunas) of NatureDocument6 pagesChart of The Three Modes (Gunas) of NaturecvdevolNo ratings yet

- Arjun Resume1Document3 pagesArjun Resume1Garunendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Indian Technical Arbitrators DirectoryDocument94 pagesIndian Technical Arbitrators DirectoryMichael GloverNo ratings yet

- Jagadguru Swami Rambhadracharya - Ayodhya Verdict - WikipediaDocument25 pagesJagadguru Swami Rambhadracharya - Ayodhya Verdict - WikipediaShashanka PandaNo ratings yet

- Stories of Lord KrishnaDocument14 pagesStories of Lord KrishnaMadhumathi Vimal SudarsanNo ratings yet

- Theravada Mahayana BuddhismDocument4 pagesTheravada Mahayana BuddhismHan Sang KimNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Excel WorksheetDocument178 pagesNew Microsoft Office Excel WorksheetAnonymous 8bqKrdNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 1Document17 pages10 - Chapter 1AahahaNo ratings yet

- Identifying Types of Nouns Grammar ExerciseDocument5 pagesIdentifying Types of Nouns Grammar ExerciseAhmed AwanNo ratings yet

- Phytoconstituents, Traditional Medicinal Uses and Bioactivities of Tulsi (Ocimum Sanctum Linn.) : A ReviewDocument4 pagesPhytoconstituents, Traditional Medicinal Uses and Bioactivities of Tulsi (Ocimum Sanctum Linn.) : A ReviewCDB 1st Semester 2077No ratings yet

- Diana Paxson - UtgardDocument13 pagesDiana Paxson - UtgardPablo RunaNo ratings yet

- Attendance Sheet of B.tech 2022 BatchDocument11 pagesAttendance Sheet of B.tech 2022 BatchGAURAV CHHETRINo ratings yet

- A Sufi View of Rebirth - Bawa MuhaiyaddeenDocument11 pagesA Sufi View of Rebirth - Bawa MuhaiyaddeenmasudiqbalNo ratings yet

- Saravanan G HR ProfileDocument2 pagesSaravanan G HR ProfileSaravananGaneshanNo ratings yet

- Sociology and Anthropology Generic Course Syllabi II Sem 12-13-1Document13 pagesSociology and Anthropology Generic Course Syllabi II Sem 12-13-1Jaymar ReponteNo ratings yet

- Guntur Dist Energy Department ResultsDocument98 pagesGuntur Dist Energy Department ResultstejaNo ratings yet

- Kriya GitaDocument17 pagesKriya GitaTodd Wilder100% (4)

- Cir 2021524800Document13 pagesCir 2021524800Srishti GaurNo ratings yet

- Final Teams 2nd CRM 1st RoundDocument7 pagesFinal Teams 2nd CRM 1st RoundkirthikaNo ratings yet

- Ari Linzy - Soho Tantric Sex AdDocument4 pagesAri Linzy - Soho Tantric Sex AdExtortionLetterInfo.comNo ratings yet

- JammuandKashmir-AtaGlance 3Document3 pagesJammuandKashmir-AtaGlance 3rahul golaNo ratings yet

- Yoga Nidra 2018Document16 pagesYoga Nidra 2018Bhaskar PitlaNo ratings yet

- The Forty-Eight Vows of Amitabha BuddhaDocument18 pagesThe Forty-Eight Vows of Amitabha BuddhajamesNo ratings yet

- How MahaVastu Experts Suggest Fixing Home Energy Imbalances Without DemolitionDocument5 pagesHow MahaVastu Experts Suggest Fixing Home Energy Imbalances Without DemolitionAnonymous PGXdnFd0No ratings yet

- BDS 4th Year Aug - 2018 PDFDocument11 pagesBDS 4th Year Aug - 2018 PDFSumeet SodhiNo ratings yet

- Sil 2009Document10 pagesSil 2009Peabyru PuitãNo ratings yet

- Why Bilingual Dictionaries Are InsufficientDocument17 pagesWhy Bilingual Dictionaries Are Insufficientसु॰ओ॰क॰No ratings yet

- Teutonic Mythology - RydbergDocument392 pagesTeutonic Mythology - RydbergOl Reb100% (5)