Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Measuring The Vocabulary Knowledge of Second Language Learners

Uploaded by

Chưa Đặt TênOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Measuring The Vocabulary Knowledge of Second Language Learners

Uploaded by

Chưa Đặt TênCopyright:

Available Formats

Measuring the Vocabulary Knowledge of Second Langauge

Learners

John Read

Victoria University of Wellington

New Zealand

Abstract

There is renewed recognition these days of the importance of

vocabulary knoweldge for second language learners. This means that

it is often necessary to find out, for diagnostic and for research pur-

poses, how many words are known by particular learners. In order to

measure vocabulary size, we need to deal with three methodological

problems: defining what a word is; selecting a suitable sample of

words for testing; and determining the criterion for knowing a word.

A first attempt to produce a diagnostic test of this kind for EAP

learners is represented by the Vocabulary Levels Test, which uses a

matching format to measure knowledge of words at five frequency

levels. The development of the test is outlined, followed by an

analysis of the results obtained from a group of learners at Victoria

University. Another approach, the checklist, is proposed as an alter-

native testing format. The literature on the checklist is reviewed, with

particular reference to methods of controlling for the tendency of

learners to overrate their knowledge of the words.

Vocabulary is a component of language proficiency that has received

comparativerly little attention in language testing since the general move

towards more integrative formats. The testing of word knowledge was a

core element of the discrete-point philosophy but with changing ideas

about the concept of language test validity it has tended to be neglected

in favour of higher level skills and processes, so that vocabulary is seen as

just one of the numerous elements that contribute to the learner’s overall

performance in the second language. However there seems to be a grow-

ing recognition of the importance of vocabulary and the need for more

systematic vocabulary development for second language learners, many

of whom are severely hampered in reading comprehension and other

skills by a simple lack of word knowledge. Since the standard types of in-

tegrative tests do not provide a direct assessment of this knowledge in a

form that is useful for diagnostic purposes, there is a need to develop

tests to determine whether specific learners have achieved a mastery of

vocabulary that is sufficient for their needs and, if they have not, what

can be done pedagogically to help them.

Interests in vocabulary testing can have both a practical and a more

theoretical focus. On the practical side, at the English Language Institute

12

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

in Wellington we have traditionally placed great emphasis on the acquisi-

tion of vocabulary in our English proficiency course for foreign students

from Asia and elsewhere who are preparing to study in New Zealand uni-

versities. This emphasis derives in part from the results of studies by Bar-

nard (1961) in India and Quinn (1968) in Indonesia, which both provided

evidence of the low level of English vocabulary knowledge among

university students in Asia, even after extensive study of English at the

secondary level. Quinn found, for example, that the average university

entrant in his sample had a vocabulary of 1,000 words after six years of

study, which represented a learning rate of little more than one word for

each class hour of English instruction. Such limited vocabularies were

clearly inadequate to meet the demands of English-medium university

studies. The Institute has thus given a high priority to intensive vocabu-

lary learning in its proficiency course and has developed a variety of

teaching resources for this purpose, including in particular the commer-

cially published workbooks by Barnard (1971-75), who pioneered the

work in this area. In this context, there is a particular need for diagnostic

testing to asseses the vocabulary knowledge of specific learners in order

to assist in making placement decisions and in designing effective pro-

grammes of vocabulary development for the various groups on the

course. On a more theoretical level, we are investigating the effectiveness

of various types of vocabulary test as tools in ongoing research studies on

vocabulary size, the nature of vocabulary knowledge and the role of

vocabulary in reading comprehension.

Some Methodological Issues

The basic question in a diagnosis of a learner’s vocabulary know-

ledge is simply: how many words does the learner know? The question is

easy to frame but rather more difficult to answer. Since comparatively

little work has been done in this area with second language learners, we

need to turn to the literature on the vocabularies of native speakers in

order to clarify the issues involved.

There has been a great deal of research on vocabulary size, extending

back to the end of the last century, and learned speculation on the sub-

ject goes back much further. The research has been beset by methodolo-

gical problems, which are discussed in detail elsewhere (see, e.g. Lorge &

Chall, 1963; Anderson & Freebody, 1981). In summary, the three main

issues are as follows:

i What is a word?

ii How should a sample of words be selected?

iii What is the criterion for knowing a word?

13

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

Let us now consider each of these in turn, as they relate to assessing

the vocabulary knowledge of learners studying English for academic pur-

poses.

i What is a word?

The first problem is simply to define what a word is. For instance,

are depend, depends, depended and depending to be classified as one

word or four? And how about dependent, dependant, dependence and

dependency? That is, one has to decide whether a ’word’ is an individual

word form or a word family (or lemma) consisting of a base form together

with the inflected and derived forms that share the same meaning. In-

cluding all such forms as separate words will clearly increase the estimate

of vocabulary size, whereas a more conservative approach results in a

substantially lower figure. The latter approach seems more realistic, even

though it requires a careful definition of criteria for grouping words into

families and even then involves some difficult problems of classification

(see Nagy & Anderson, 1984, for a useful discussion of this issue). For

practical purposes, then, we assume that word forms can be classified into

lemmas, which can be represented in a vocabulary test by a base word.

Thus, we take it that in most cases, if one knows the base word, little if

any additional learning is required in order to understand its various in-

flectional and derived forms.

ii How should sample of words be selected?

a

Since we cannot usually test all of the words that a learner may

know, it is necessary to find some basis for selecting a representative

sample of words to be used in making the estimate of vocabulary size. In

studies of native speakers, dictionaries have been most commonly used

for this purpose but the result is that estimates vary widely depending on .

the size of the particular dictionary chosen and the method of sampling

that was followed. An alternative approach involves sampling words

progressively from the higher to lower levels of a word frequency count.

This has not proved very successful with native speakers, because of the

limited coverage of the existing frequency counts and the fact that native

speakers know many words that do not find their way into such counts.

However, this approach is more appropriate with second language

learners, especially those in EFL countries with little or no exposure to

municative needs are also typically more limited. For many groups of

learners, especially those in EFL countries wtih little or no exposure to

the language outside the classroom, the General Service List (West, 195 3)

represents a fairly complete sampling frame of the words they are likely

to know, even after several years of study. And in fact a number of ESL

vocabulary studies (e.g. Barnard, 1961; Quinn, 1968; Harlech-Jones,

1983) have used the list for this purpose.

14

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

Beyond the minimum vocabulary of the General Service List, it is

necessary to take account of the needs and interests of specific groups of

learners in planning for vocabulary teaching and testing. Our particular

concern here is with the vocabulary of English for academic study at the

tertiary level. The task is to identify and teach the set of words (often

referred to as ’subtechnical’ vocabulary) that occur frequently in acade-

mic study at the tertiary level. The task is to identify and teach the set of

words (often referred to as ’subtechnical’ vocabulary) that occur fre-

quently in academic discourse across various disciplines. Knwoledge of

the meanings of these words is normally assumed by lecturers and authors

in a particular academic field and among other things this vocabulary has

a crucial role in defining the technical terms of each field of study.

A number of specialized word lists for academic English have been

produced. Typically these are based on a count of words occurring in

university textbooks and other academic writing material, taking into ac-

count the range of disciplines in which the words are found as well as the

number of occurrences. The list is compiled by excluding both high fre-

quency general words (such as those in the General Service List) and low

frequency, narrow range words which consist largely of technical termin-

ology. The most comprehensive work along these lines is that of Barnard,

who has not only prepared two 1,000-word lists (in Nation, 1986) but

also written a series of widely used workbooks (Barnard, 1971-75) to

help students to learn the words. Other similar, though shorter lists were

compiled by Campion and Elley (1971) and Praninskas (1972). Two

more scholars, Lynn (1973) and Ghadessy (1979) adopted a different ap-

proach, by scanning student copies of textbooks to identify and count

words that were frequently annotated with a mother-tongue translation

or some other explanation. These words turned out to be very much the

same ones that were included in the other lists. As Lynn (1973:26) noted

specifically, it was the general academic words, rather than technical

terms, that appeared to be the most difficult for the students.

Xue and Nation (1984) combined the lists of Campion and Elley,

Praninskas, Lynn and Ghadessy into a single University Word List, which

shares much in common with the Barnard lists but has the advantage of

being derived from a broader range of frequency counts. The list is ac-

companied by sublists which classify the words according to frequency

and semantic criteria and also include common derivatives of the base

forms.

For our purposes the academic word lists together with the Gene-

-

ral Service List form an inventory of high frequency words that com-

-

monly occur in academic English and account for a high proportion of

15

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

the words in any particular academic text. These are the words that re-

quire individual attention from teachers and learners in an EAP profi-

ciency course. The lists also constitute a satisfactory sampling frame for

diagnostic testing aimed at evaluating the adequacy of the learner’s voca-

bulary knowledge for undertaking academic study.

iii What is the criterion for knowing a word?

Once a sample of words has been selected, it is necessary to deter-

mine whether each word is known or not by means of some kind of test.

In studies of vocabulary size, the criterion for knowing the word has

been quite liberal, since the researcher has had to survey a large number

of words in the time available for testing. Thus the most commonly used

test formats have been the following:

-

checklists (or yes/no tests), in which the learners are presented with a

list of words and simply asked to tick the ones that they know

-

multiple choice items of various kinds

-

matching of words with their definitions.

All of these formats can be criticized as inadequate indicators of whether

the word is really known. The checklist does not require the learners to

provide any independent evidence that they know the words they have

ticked. The other two formats, multiple choice and matching, do require

the learners to associate each word with a suitable definition or synonym,

but this is only one aspect of vocabulary knowledge. We have to recognize

that words can have several meanings and, conversely, a person’s know-

ledge of a word may be partial rather than complete. Writers such as

Cronbach (1942) and Richards (1976) have identified numerous aspects

of knowing a word, such as its various meanings, its appropriate use, its

relative frequency, its syntactic properties, its connections and its links

with other words in semantic networks. From this perspective, a single

multiple choice or matching item is scarcely an adequate basis for deter-

mining whether someone knows a word and, if so, how well it is known.

However, it is useful here to distinguish between breadth and depth

of vocabulary knowledge. In setting out to estimate the size of a learner’s

vocabulary, we are focusing on breadth of knowledge: how many of the

words in a large sample are &dquo;known&dquo;, in some sense? For this purpose, a

simple -

albeit crude measure is necessary in order to cover all the

-

words in the sample within a reasonable period of time. But for other

purposes, particularly achievement testing, we need to concentrate more

on depth of knowledge: how well are smaller sets of key vocabulary items

known? The problem is that we currently lack procedures for measuring

the depth of vocabulary knowledge of second language learners. This is

16

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

an area in which research is only just beginning (see Read, 1987) and is

beyond the scope of this article. ,

These, then, are the issues that need to be resolved in assessing the

vocabulary knowledge of second language learners. In the rest of this

article, we will first look at a particular test that was designed for this

purpose using a matching format, and then go on to discuss the possibility

of using the checklist procedure as an alternative format.

A Matching Test of Vocabulary Levels

A first attempt to undertake diagnostic testing of vocabulary knowl-

edge along the lines outlined above is represented by the Vocabulary

Level Test (Nation, 1983). This instrument was designed to assess knowl-

edge of both general and academic vocabulary; therefore it includes

samples of words at five frequency levels: 2,000 words, 3,000 words,

5,000 words, the university word level (above 5,000 words) and 10,000

words. Words were selected on the basis of the frequency data in Thorn-

dike and Lorge (1944), with cross-checking against the General Several

List (for the 2,000-word level) and Kucera and Francis (1967). The one

exception was the university word level, for which the specialized count

of Campion and Elley (1971) was used. (This list excluded the first 5,000

words of Thorndike and Lorge). The test employs word-definition

matching format although, in a reversal of the standard practice, the

testees are required to match the words to the definitions. That is, the

definitions are the test items rather than the words. At each of the five

levels, there are 36 words and 18 definitions, in groups of six and three

respectively, as in the example below:

This slightly unconventional format was developed with the aim of

having an efficient testing procedure that involved as little reading as

possible and minimized the chances of guessing correctly. It was consi-

dered that, although there were only 18 words for each level, in fact 36

words would be tested because the testees’ natural test-taking strategy

would be to check each word against the definitions given in order to

make the correct matches. This was only partly confirmed by observa-

17

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

tion of individual testees as they took the test during the tryout phase.

The testees did adopt that strategy but only in sections of the test that

they found difficult; with easy items they focused directly on the correct

words and largely ignored the distractors.

All the words in each group are the same part of speech, in order to

avoid giving any clue as to meaning based on form. On the other hand,

apart from the correct matches, care was taken not to group together

words and definitions that were related in meaning. The test is designed

as a broad measure of word knowledge and it was not intended to require

the testees to differentiate between semantically related words or to show

an awareness of shades of meaning.

The test has proved to be a very useful tool for diagnostic purposes.

We have basic statistical data available from an administration of the test

during our three-month English Language Institute English Proficiency

Course (see Table 1). The test was given at the beginning of the course, to

assist with placement and course planning decisions, and again at the

end, in order to look at the stability of the instrument and the possibility

that it would reflect the effects of instruction. For both administrations,

the reliability coefficients were very satisfactory (0.94 and 0.91 respec-

tively) and there was a clear pattern of declining scores across frequency

levels from highest to lowest. However the means for the 5,000-word and

university levels were very close at the beginning of the course and in fact

their order was reversed in the second administration, for reasons that

will be discussed in a moment.

In order to provide more systematic evidence of the validity of the

division by levels, a Guttman Scalogram analysis (Hatch & Farhady,

1982) was undertaken on the two sets of scores. A score of 16 was taken

as the criterion for mastery of the vocabulary at a particular level. The

scaling statistics are given in Table 1. They show that in both cases the

scores were highly scalable. That is to say, a testee who achieved the

criterion score at a lower frequency level say, the 5,000-word level

- -

could normally be assumed to have mastered the vocabulary of higher

freauency levels 2,000 and 3,000 words - as well.

-

What is not so satisfactory from a theoretical standpoint is that there

are two different scales here, because the 5000-word and university-word

levels reverse their order from one administration to the other. There are

various possible explanations for this. First of all, the university level is

based on the specialized frequency count of Campion and Elley, whereas

the other four levels are all derived from the more general Thorndike and

Lorge count. This places the university level somewhat outside the se-

quence formed by the other levels.

18

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

Table 1. Results of the Vocabulary Level Test

(N=81) -

Secondly, the students taking the proficiency course are quite hetero-

geneous and the overall results mask some significant differences among

subgroups in the population. For instance, one group consists of teachers

of English from EFL countries in Asia and the South Pacific preparing

for a Diploma course in TESL during the following academic year. These

teachers tend to score higher at the 5-000-word level than the university

level, reflecting their familiarity with general English, including literary

19

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

works, and their relative lack of familiarity with academic or technical

registers. This was particularly evident at the beginning of the course but

was less noticeable at the end, presumably because of their exposure dur-

ing the course to academic writing and their study of the University

Word List.

On the other hand, another identifiable subgroup comprises a small

number of Latin American students who are native speakers of Spanish

or Portuguese. Unlike most of the English teachers, they are university

graduates coming to New Zealand for postgraduate studies in engineer-

ing or agriculture. The students almost all had substantially higher scores

at the university-word level than the 5000-word level. One way to explain

this is in terms of their academic background, even though it was not in

the medium of English. Another factor is that a high proportion of the

words at the university level are derived from Latin and are therefore likely

to have cognate forms in Spanish and Portuguese, with the result that

Latin American students would have a certain familiarity with them

without having learned them as English words.

A third reason for the shift in the order of levels from the first to

the second administration is that a great deal of attention is paid to aca-

demic vocabulary during the proficiency course. Almost all of the groups

work through two of the workbooks in the Advanced English Vocabulary

series (Barnard, 1971-75) and the University Word List is also used as the

basis for vocabulary learning activities. Thus, if the test is sensitive to the

effects of instruction during the course, one might expect a relatively

greater improvement in scores at the university word level than at the 5000

word level. There is some evidence from the pretest and posttest means

that this was the case.

An Alternative Measure: The Checklist

Although the Vocabulary Levels Test has proved to be a useful

diagnostic tool, we are aware of at least three possible shortcomings.

(a) It tests a very small sample of words at each level, even if we accept

that 36 words are tested rather than just 18.

(b) The matching format requires the testees to match the words with

dictionary-type definitions, which are sometimes awkwardly expressed

as the result of being written within a controlled vocabulary. Learners

may not make sense of words in quite the analytic fashion that a lexi-

cographer does.

(c) While the format was modified to reduce the role of memory and

test-taking strategy, there is still a question of the influence of the

format on testee performance.

20

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

Thus, as an alternative format, we can consider the checklist (also

called the yes/no method), which simply involves presenting learners

with a list of words and asking them to check (tick) each word that they

&dquo;know&dquo;. The exact nature of the task depends - more so than with

most other tests -

on the testees’ understanding of what they are being

asked to do, and therefore both the purpose of the test and the criterion

to be used in judging whether a word is known need to be carefully ex-

plained. As with any type of self-evaluation, it is not suitable for grading

or assessment purposes, but it has definite appeal as an instrument in

vocabulary research, especially since it is an economical way of surveying

knowledge of a large number of words.

A review of the literature on the checklist method reveals that it is

one of the oldest approaches to testing the vocabulary of native speakers:

Melka Teichroew (1982:7) traces it back as far as 1890. Early studies

investigated the validity of the procedure by correlating a checklist test

with other types of test such as multiple choice or matching. These

studies involved native-speaking school children and the findings were

variable. For example, Sims (1929) found that his checklist did not corre-

late well with three other tests and concluded that it was not measuring

knowledge of word meaning but simply familiarity with the words from

having frequently encountered them in reading and school work. On the

other hand, Tilley (1936) obtained a high correlation between a checklist

and a standardized multiple choice test in his investigation of the relative

difficulty of words for students at three different grade levels. The rela-

tionship was somewhat stronger for older and for more intelligent child-

ren.

One obvious problem in a checklist test is overrating the tendency -

of at least some students to tick words that they do not actually know -

and more recent studies have sought to control for this. As part of their

project to develop an academic vocabulary list based on a word frequency

count of university textbooks, Campion and Elley (1971) asked senior

high school students to rate each word according to whether they could

attribute a meaning to it if they encountered it in their reading. The per-

centage of positive responses was taken as an index of the familiarity of

the word for university-bound students. The ratings correlated reasonably

well (at 0.77) with the results of a word-definition matching test.

The innovative feature in Campion and Elley’s study was their

method of controlling for overrating. The subjects of this study were

divided into groups, which each rated a different subset of the words in

the list. However each sublist included a number of &dquo;anchor&dquo; words,

which were thus rated by all of the subjects. The mean ratings of the an-

chor words were calculated and these were used in a norm-referenced fas-

21

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

hion to evaluate the performance of the various groups. When a group

was found to have rated the anchor words significantly differently from

the overall means, the ratings of the words on its sublist were adjusted as

appropriate.

Another approach to this problem has been adopted by Anderson

and Freebody (1983). They prepared a vocabulary checklist containing a

high proportion (about 40 per cent) of &dquo;nonwords&dquo;, which were created

either by changing letters in real words (e.g. porfame from perfume) or

by forming novel base-and-affix combinations (e.g. observement). The

ticking of these nonwords was taken as evidence of a tendency to overrate

one’s knowledge of the real words, and a simple correction formula was

applied (similar to a correction for guessing) to adjust the scores accord-

ingly. The corrected scores were found to correlate much more highly

with the criterion -

the results of an interview procedure - than did

scores on a multiple choice test of the words. In a subsequent study on

learning words from context, Nagy, Herman and Anderson (1985) used a

similar checklist test as a measure of the subjects’ prior knowledge of the

target words. In this case complete nonwords such as felinder and werpet

were included in the checklist, in addition to the other two types, and it

was only this third category of nonwords that was used in making the

corrections of subjects’ scores.

Up until now there appears to have been little use made of the check-

list approach in studies of the vocabulary of second language learners,

but recently Meara and Jones (1987) used a checklist containing nonsense

words for an English vocabulary test designed as a possible placement

measure for adult ESL learners enrolling in Eurocentres in Britain. They

went one step further and programmed the test for administration on a

microcomputer. The computer selects items in descending order of fre-

quency from each thousand of the first 10,000 words of English, based

on the Thorndike and Lorge (1944) list, with nonsense words being in-

cluded at a rate of one to every two authentic words. The words are

presented one at a time on the screen and the learner simply presses a key

on the keyboard to indicate whether she or he knows the meaning of each

word. Meanwhile the computer progressively estimates the size of the

learner’s vocabulary making the appropriate correction for guessing,

-

where necessary -

and terminates the test when the upper limit of the

learner’s knowledge has been reached.

Since these researchers were primarily interested in the vocabulary

test as aplacement measure, they validated it by reference to the existing

Eurocentre placement test (consisting of grammar, listening and reading

subtests), rather than using another measure of vocabulary knowledge.

22

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

However, one analysis of their results showed that. in general, the

learners knew progressively fewer of the words at each succeeding fre-

quency level. The regularity of the pattern differed considerably, though,

according to the L of the learners, from highly regular for the Japanese

to somewhat anomalous in the case of Romance language speakers, espe-

cially speakers of French. (This finding is interesting in view of the simi-

larly distinctive performance of the Spanish speakers on the ELI

Vocabulary Levels Test, as noted above.) Clearly, as the authors point

out, further research is needed to establish the reliability and validity of

the test as a measure of vocabulary knowledge and to account for the

variation in results according to the learner’s L 1.

There are practical limitations on the widespread use of this parti-

cular test, since it is administered individually by computer, but a pen-

and-paper version based on the same principles should not be difficult to

construct and would be a useful alternative to the Vocabulary Levels

Test.

A checklist test, then, has much to recommend it as a broad measure

of vocabulary knowledge, especially if it incorporates a correction proce-

dure for overrating. The simplicity of the test is a significant advantage.

As Anderson and Freebody note, &dquo;it strips away irrelevant task demands

that may make it difficult for young readers and poor readers to show

what they know&dquo; (1983:235). It does not require the kind of testwiseness

that influences performance in multiple choice or matching tests. A

related attraction is that a much larger number of words can be assessed

by the checklist in a given period of time, as compared to other types of

vocabulary test.

Conclusion

In this article, we have seen how it is possible to draw a stratified

sample of words from a general frequency list or from a more specialized

inventory such as the University Word List and then use the matching or

checklist format to estimate how many words in the total list the learner

knows. This is a valuable procedure for placement purposes and in voca-

bulary research. It should be emphasized again that we are concerned

here with the breadth of a learner’s knowledge of vocabulary and so the

tests that are used for this purpose do not address the issue of the depth

of knowledge: does the learner really know particular words and, if so,

how well? There are in fact complementary approaches to the study of

word knowledge, and we need more investigation of both with second

language learners in order to advance our understanding of the way in

which vocabulary knowledge is acquired and exploited.

23

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

Note

’This is a reworked version of a paper entitled "Some Issues in the

Testing of Vocabulary Knowledge", which was presented at LT + 25 : A

Language Testing Symposium in Honor of John B. Carroll and Robert

Lado, at Quiryat Anavim, Israel, 11-13 May 1986.

References

Anderson, R.C. and Freebody, P. 1981. Vocabulary knowledge. In

Guthrie, J.T., editor, Comprehension and teaching: research

reviews. Newark, Delaware: International Reading Association

1983. Reading comprehension and the assessment and acquisi-

tion of word knowledge. In Huston, B., editor, Advances in read-

ing/language research. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press.

Barnard, H. 1961. A test of P.U.C. students’ vocabulary in Cho-

tanagpur. Bulletin of the Central Institute of English 1:90-100.

1971-75. Advanced English vocabulary. Workbooks 1-3. Row-

ley, Massachusetts: Newbury House.

Campion, M.E. and Elley, W.B. 1971. An academic vocabulary list.

Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Cronbach, L.J. 1942. An analysis of techniques for diagnostic vocabulary

testing. Journal of Educational Research 36, 206-217.

Ghadessy, M. 1979. Frequency counts, word lists, and materials prepara-

tion : a new approach. English Teaching Forum 17, 24-27.

Harlech-Jones, B. 1983. ESL proficiency and a word frequency count.

English Language Teaching Journal 37, 62-70.

Hatch, E. and Farhady, H. 1982. Research design and statistics for applied

linguistics. Rowley, Massachusetts: Newbury House.

Kucera, H. and Francis, W.M. 1967. A computational analysis of present

day American English. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown Univer-

sity Press.

Lorge, I. and Chall, J. 1963. Estimating the size of vocabularies of child-

ren and adults: an analysis of methodological issues. Journal of Ex-

perimental Education 32, 147-57.

Lynn, R.W. 1973. Preparing word lists: a suggested method. RELC

Journal 4, 25-32.

Meara, P. and Jones, G. 1987. Tests of vocabulary size in English as a

foreign language. Polyglot 8:1, 1-40.

Melka Teichroew, F.J. 1982. Receptive versus productive vocabulary: a

survey. Interlanguage Studies Bulletin 6, 5-33.

24

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

Nagy, W.E. and Anderson, R.C. 1984. The number of words in printed

school English. Reading Research Quarterly 19, 304-330.

_, Herman, P.A. and Anderson, R.C. 1985. Learning words

from context. Reading Research Quarterly 20, 233-53.

Naton, I.S.P. 1983. Testing and teaching vocabulary. Guidelines 5, 12-25.

1986. Vocabulary lists: words, affixes and stems. Revised edi-

tion. Wellington, New Zealand: English Language Institute, Victo-

ria University.

Praninskas, J 1972. American university word list. London: Longman.

Quinn, G. 1968. The English vocabulary of some Indonesian university

entrants. Salatiga, Indonesia: IKIP Kristen Satya Watjana.

Read, J. 1987. Towards a deeper assessment of vocabulary knowledge.

Paper presented at the 8th World Congress of Applied Linguistics,

Sydney, Australia, 16-21 August.

Richards, J.C. 1976. The role of vocabulary teaching. TESOL Quarterly

10, 77-89.

Sims, V.M. 1929. The reliability and validity of four types of vocabulary

tests. Journal of Educational Research 20, 91-6.

Thorndike, E.L. and Lorge, I. 1944. The teacher’s word book of 30,000

words. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Tilley, H.C. 1936. A technique for determining the relative difficulty of

word meanings among elementary school children. Journal of Ex-

perimental Education 5, 61-4.

West, M. 1953. A general service list of English words. London: Long-

mans, Green.

Xue, Guo-yi and Nation, P. 1984. A university word list. Langauge

Learning and Communication 3, 215-29.

25

Downloaded from rel.sagepub.com at UNIV ALABAMA LIBRARY/SERIALS on December 19, 2014

You might also like

- Understanding The Seven Learning StylesDocument5 pagesUnderstanding The Seven Learning StylesChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- (123doc) - The-Impact-Of-Repetition-And-Recycling-On-Grade-11-Students-Vocabulary-Retention-In-Long-Hai-Phuoc-Tinh-High-SchoolDocument6 pages(123doc) - The-Impact-Of-Repetition-And-Recycling-On-Grade-11-Students-Vocabulary-Retention-In-Long-Hai-Phuoc-Tinh-High-SchoolChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Mass Communication and The Work ofDocument14 pagesRevisiting Mass Communication and The Work ofChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Works: - and What You Can Doto Improve YoursDocument8 pagesWorks: - and What You Can Doto Improve YoursChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Challenges For Methods of Teaching English Vocabulary To Non-Native StudentsDocument20 pagesChallenges For Methods of Teaching English Vocabulary To Non-Native StudentsChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- The Use of Non - Verbal Communication in The Teaching of English LanguageDocument7 pagesThe Use of Non - Verbal Communication in The Teaching of English LanguageChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Analysis For Language Course Design PDFDocument11 pagesAnalysis For Language Course Design PDFChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Applying Montessori Method To Improve EaDocument15 pagesApplying Montessori Method To Improve EaChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Final Report English Language Training 80465Document55 pagesFinal Report English Language Training 80465Chưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- The Utilization of Instructional Material and Nursery School Effectiveness in Ebira Land Chapter One Background To The StudyDocument40 pagesThe Utilization of Instructional Material and Nursery School Effectiveness in Ebira Land Chapter One Background To The StudyChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Môn Anh Văn-Khối 11: 1) A. noticed B. turned C. changed D. imagined 2) A. sneaky B. cream D. believeDocument5 pagesMôn Anh Văn-Khối 11: 1) A. noticed B. turned C. changed D. imagined 2) A. sneaky B. cream D. believeChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- The Dispute Over Defining CultureDocument25 pagesThe Dispute Over Defining CultureChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- De Cuong Tu Luan Tieng Anh 11 de Cuong Tu Luan Tieng Anh 11Document9 pagesDe Cuong Tu Luan Tieng Anh 11 de Cuong Tu Luan Tieng Anh 11Chưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Hands-On Activity - Week 6Document4 pagesHands-On Activity - Week 6Chưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Art Project Ideas Painting Projects For PDFDocument19 pagesArt Project Ideas Painting Projects For PDFChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Anh Van 11 Dap An - hk1Document92 pagesAnh Van 11 Dap An - hk1Chưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Instructional Materials: Presenter: Trinh Yen NhiDocument5 pagesInstructional Materials: Presenter: Trinh Yen NhiChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Eco3310.501.07f Taught by Ozge Ozden (Oxe024000)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Eco3310.501.07f Taught by Ozge Ozden (Oxe024000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Action Plan in Mathematics SY 2019-2020: Prepared By: Approved byDocument2 pagesAction Plan in Mathematics SY 2019-2020: Prepared By: Approved byAldrin Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Learning Competency:: Weekly Home Learning PlanDocument3 pagesLearning Competency:: Weekly Home Learning PlanJohn Caezar YatarNo ratings yet

- Eei Technology Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesEei Technology Lesson Planapi-285995221100% (1)

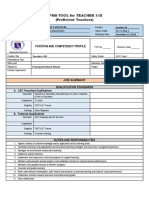

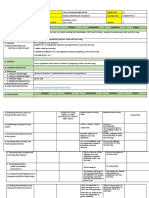

- Rpms Tool For Teacher I-Iii (Proficient Teachers) : Position and Competency ProfileDocument26 pagesRpms Tool For Teacher I-Iii (Proficient Teachers) : Position and Competency ProfileRheinjohn Aucasa Sampang100% (1)

- UOS Marking SchemeDocument7 pagesUOS Marking SchemeJoseph SelvarajNo ratings yet

- 1.4micrometer Screw GaugeDocument3 pages1.4micrometer Screw GaugeHusNa RadziNo ratings yet

- What's IQDocument11 pagesWhat's IQzoology qau100% (1)

- Understanding Why Creative and Critical Thinking Skills Are ImportantDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Why Creative and Critical Thinking Skills Are ImportantGlen Carlo B. RellosoNo ratings yet

- Cookery DLLDocument19 pagesCookery DLLChristina Manguiob Escasinas100% (1)

- Bett - Phase 5Document34 pagesBett - Phase 5Anuja DamleNo ratings yet

- B. SPT Memo TOR MAESDocument8 pagesB. SPT Memo TOR MAESEVA NOEMI ABAYONNo ratings yet

- Minutes of Lac SessionDocument1 pageMinutes of Lac SessionKsths Oplan OrasanNo ratings yet

- YOB Preschool ProposalDocument22 pagesYOB Preschool ProposalVinod Kumar Brain GuruNo ratings yet

- Community College DisadvantagesDocument1 pageCommunity College DisadvantagesRhelbamNo ratings yet

- Adult Learning Students Guidebook-1Document23 pagesAdult Learning Students Guidebook-1salmaNo ratings yet

- Humanities Abstracts: "Margaret C. Anderson's Little Review"Document22 pagesHumanities Abstracts: "Margaret C. Anderson's Little Review"franxyz14344No ratings yet

- Scaffolding Content and Language Demands For "Reclassified" StudentsDocument7 pagesScaffolding Content and Language Demands For "Reclassified" Studentsapi-506389013No ratings yet

- Revised Research CapstoneDocument51 pagesRevised Research CapstoneHaziel Joy GallegoNo ratings yet

- Writing Learning ObjectivesDocument2 pagesWriting Learning ObjectivesĐạt HuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - Day 4 I. Objectives: V Xkmhs4Qlj - S Tsyo4Z0EDocument8 pagesWeek 2 - Day 4 I. Objectives: V Xkmhs4Qlj - S Tsyo4Z0EBRIGIDA V.ADOPTANTENo ratings yet

- TG Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocument223 pagesTG Understanding Culture, Society and Politicsنجشو گحوش100% (7)

- Dressing UpDocument28 pagesDressing Uptutorial 001No ratings yet

- Detailed Science Lesson Plan 1Document2 pagesDetailed Science Lesson Plan 1Lorraine DonioNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Selection of MaterialsDocument6 pagesGuidelines For Selection of MaterialsAlfeo OriginalNo ratings yet

- DLL Abegail C. Estacio EditedDocument80 pagesDLL Abegail C. Estacio EditedAbegail Castaneda EstacioNo ratings yet

- User Manual On Ifps Usage and Byjus App UsageDocument120 pagesUser Manual On Ifps Usage and Byjus App UsageA PADMAJA JNTUK UCEVNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Girls InsideDocument16 pagesBeautiful Girls InsideEnglishUrduDiaryNo ratings yet

- CI 402 Class Simulation MLK Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesCI 402 Class Simulation MLK Lesson Plankklemm89No ratings yet

- Post Test Result Project Emtap 2.0Document19 pagesPost Test Result Project Emtap 2.0Gener Taña AntonioNo ratings yet