Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0003-3219 (2004) 074 0361 Cotcba 2 0 Co 2

Uploaded by

Andrea Cárdenas SandovalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

0003-3219 (2004) 074 0361 Cotcba 2 0 Co 2

Uploaded by

Andrea Cárdenas SandovalCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Correlation of the Cranial Base Angle and Its Components

with Other Dental/Skeletal Variables and Treatment Time

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article-pdf/74/3/361/1372815/0003-3219(2004)074_0361_cotcba_2_0_co_2.pdf by Colombia user on 09 March 2021

Louis M. Andria, DDS, MS, FICDa; Luis P. Leite, DDS, MSb; Tracie M. Prevatte, BSc;

Lydia B. King, MPHd

Abstract: Many authors have studied the correlation of cranial base flexure and the degree of mandibular

prognathism and classification of malocclusion. This indicates that the cranial base flexure may or may

not have an effect on the degree of mandibular prognathism and classification of malocclusion. This study

evaluates the correlation of the pretreatment cranial base angle and its component parts to other dental and

skeletal cephalometric variables as well as treatment time. The sample consisted of 99 Angle Class II and

Class I malocclusions treated in the mixed dentition with cervical headgear and incisor bite plane. Thirty

of the patients required full appliance treatment. Treatment duration averaged 4.3 years (SD, 1.5 years).

Only the starting cephalograms were used to acquire linear, proportional, and angular cranial base dimen-

sions using Ba-S-N (total cranial base), Ba-S/FH (posterior cranial base), and SN/FH (anterior cranial

base). Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were computed and used to assess the association

of the following skeletal and dental variables: N-Pg/FH, MP/FH, Y-axis/FH, U1/L1, L1/MP, A-NPg mm,

A-Perp, B-Perp, and treatment time with the cranial base measurements. Significance was determined only

when the confidence level was P , .05. Although there was no significant correlation of BaSN or SN/FH

with NPg, the angular BaS/FH, linear BaS mm, and proportional length of BaS %BaN were all statistically

negatively correlated to the facial angle. This indicates that the posterior cranial base leg is the controlling

factor in relating the cranial base to mandibular prognathism. (Angle Orthod 2004;74:361–366.)

Key Words: Cranial base; Mandibular protrusion; Correlation coefficients; Posterior cranial base leg;

Treatment time

INTRODUCTION terior leg that extends from the sella turcica (S) to the fron-

tal-nasal suture (N). The mandible is attached to the pos-

There is an abundance of contradictory literature relating terior leg extending from the sella turcica (S) to the anterior

the cranial base flexure to the classification of malocclusion border of the foramen magnum, defined as basion (Ba).

and the degree of mandibular prognathism. One group con- Therefore, geometric logic would dictate that any change

tends that the cranial base flexure has no effect on the class in flexure could affect the relationships of the maxilla and

of malocclusion or mandibular prognathism,1–11 whereas mandible and influence the type of malocclusion.

others contend that the cranial base flexure is a factor.12–28 This investigation tests several null hypotheses on the

The cranial base consists of two legs. For cephalometric effect of the cranial base angle on skeletal profile and dental

measurement purposes, the maxilla is attached to the an- relationship.

• The cranial base angle (BaSN) and its component parts

a

Adjunct Associate Professor, Pediatric Dentistry/Orthodontics, (BaS/FH and SN/FH) will have no effect on the maxilla

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC. and mandible positions in the profile.

b

Associate Professor, Pediatric Dentistry/Orthodontics, Medical

• The cranial base angle and its component parts will have

University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

c

Dental Student, College of Dentistry, Medical University of South no influence on the alveolar positions in the profile.

Carolina, Charleston, SC. • The cranial base angle and its component parts will have

d

Graduate Resident, College of Medicine Biometry and Epidemi- an effect on incisor relationships.

ology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC. • The cranial base angle and its component parts will have

Corresponding author: Louis M. Andria, DDS, MS, FICD, Pedi-

no relationship to the length of treatment time.

atric Dentistry/Orthodontics, Medical University of South Carolina,

25 Bee Street, PO Box 250126, Charleston, SC 29425

(e-mail: louandria@nuvox.net). MATERIALS AND METHODS

Accepted: July 2003. Submitted: June 2003. Pretreatment cephalometric records of 99 Angle Class II

q 2004 by The EH Angle Education and Research Foundation, Inc. and Class I male and female patients were selected at ran-

361 Angle Orthodontist, Vol 74, No 3, 2004

362 ANDRIA, LEITE, PREVATTE, KING

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article-pdf/74/3/361/1372815/0003-3219(2004)074_0361_cotcba_2_0_co_2.pdf by Colombia user on 09 March 2021

FIGURE 3. Cranial base and middle-face depth.

alies, significant facial asymmetries, or congenitally miss-

ing teeth; and (3) records for each patient included dental

FIGURE 1. Cephalometric landmarks. casts, facial photographs, full mouth, or panoramic radio-

graphs and lateral cephalometric head films. Pretreatment

starting records were selected for the study. Each starting

cephalometric head film was traced, and both midline and

bilateral images were traced. All bilateral images were bi-

sected and thereafter treated as midline structures inasmuch

as the cranial base is a midline structure. Linear measure-

ments were read to the nearest 0.05 mm, and all angular

measurements were read with a standard protractor to the

nearest 0.058. A right-angle coordinate system, as described

by Coben,29 was used to determine proportions relative to

total cranial base length. The presence of clinical treatment

folders enabled the inclusion of treatment time. The mean

treatment time was 4.3 years with a standard deviation 1.5

years.

Pearson product moment correlation coefficients and P

values were computed for each of the cranial base mea-

surements Ba-S-N (total cranial base), Ba-S/FH (posterior

cranial base), and SN/FH (anterior cranial base) with the

following variables: N-Pg, MP/FH, Y-axis/FH, U1/L1, L1/

MP, A-NPg mm, A-Perp, B-Perp, BaS %BaN, and treat-

ment time. Significance was determined only when the con-

FIGURE 2. Cephalometric planes.

fidence level was P , .05.

Cephalometric landmarks and measurements

dom from the files from one of the author’s private practice

and donated to the Pediatric Dentistry/Orthodontic Depart- The landmarks and planes used are presented in Figures

ment at the Medical University of South Carolina. There 1 and 2. Linear measurements were acquired by projecting

were 34 males and 65 females, and the mean age of the cranial landmarks at right angles to Frankfort horizontal

patients was 9.7 years with a standard deviation of two (Figure 3). A right-angle coordinate system was used to

years. All patients were treated in the mixed dentition, with determine proportional data.29 The position of the alveolar

30 requiring fixed-appliance therapy. The criteria used in bases were determined by relating A to the facial plane and

selection were as follows: (1) lateral cephalometric head points A and B as perpendicular to Frankfort horizontal and

films were of excellent quality with clearly visible cepha- recording the linear distance from the facial plane (A and

lometric landmarks; (2) no patients had congenital anom- B perpendicular). The legs of the cranial base angle and

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 74, No 3, 2004

CORRELATION OF THE CRANIAL BASE AND TREATMENT TIME 363

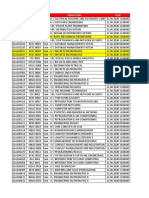

TABLE 1. Correlation of Cranial Base Angle with Other Cephalo- TABLE 3. Correlation of Anterior Cranial Base Angle with Other

metric Variables Cephalometric Variables

Correlation Correlation

Variable Coefficient P Variable Coefficient P

BaSN with BaS/FH .917715 ,.0001* SN/FH with facial angle .181484 ..05

BaSN with SN/FH .643815 ,.0001* SN/FH with mandibular plane 2.090229 ..05

BaSN with facial angle 2.166264 ..05 SN/FH with Y-axis 2.27219 .0064*

..05

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article-pdf/74/3/361/1372815/0003-3219(2004)074_0361_cotcba_2_0_co_2.pdf by Colombia user on 09 March 2021

BaSN with mandibular plane .016222 SN/FH with interincisal angle .047725 .05

BaSN with Y-axis 2.017093 ..05 SN/FH with lower incisor to MP 2.063338 ..05

BaSN with interincisal angle 2.087958 ..05 SN/FH with A-NPg 2.101069 ..05

BaSN with lower incisor to MP .114729 ..05 SN/FH with A-Perp .082349 ..05

BaSN with A-NPg .032453 ..05 SN/FH with B-Perp .095109 ..05

BaSN with A-Perp 2.073202 ..05 SN/FH with BaS %BaN .251986 .02552*

BaSN with B-Perp 2.169722 ..05 SN/FH with treatment time 2.103519 ..05

BaSN with BaS %BaN .799225 ,.0001*

* Statistically significant.

BaSN with treatment time 2.181916 ..05

* Statistically significant.

TABLE 4. Correlation of Posterior Cranial Base Linear Length with

Other Cephalometric Variables

TABLE 2. Correlation of Posterior Cranial Base Angle with Other Correlation

Cephalometric Variables Variable Coefficient P

Correlation BaS mm with BaSN .748958 ,.0001*

Variable Coefficient P BaS mm with BaS/FH .827113 ,.0001*

BaS/FH with facial angle 2.30349 .0023* BaS mm with SN/FH .206977 .0039*

BaS/FH with mandibular plane .073017 ..05 BaS mm with facial angle 2.28054 .0052*

BaS/FH with Y-axis .122036 ..05 BaS mm with MP/FH .105706 ..05

BaS/FH with interincisal angle 2.132781 ..05 BaS mm with Y-axis .173118 ..05

BaS/FH with lower incisor to MP .169976 ..05 BaS mm with U1/L1 2.19377 ..05

BaS/FH with A-NPg .095684 ..05 BaS mm with lower incisor to MP 2.241258 .0172*

BaS/FH with A-Perp 2.13402 ..05 BaS mm with A-NPg .162245 ..05

BaS/FH with B-Perp 2.263645 .0084* BaS mm with A-Perp 2.11799 ..05

BaS/FH with BaS %BaN .867678 ,.0001* BaS mm with B-Perp 2.23399 .019*

BaS/FH with treatment time 2.175447 ..05 BaS mm with treatment time 2.25442 .011*

* Statistically significant. * Statistically significant.

TABLE 5. Correlation of Proportional Cranial Base Length with

facial and mandibular plane angles were related to the Other Cephalometric Variables

Frankfort horizontal. Correlation

Variable Coefficient P

RESULTS

BaS %BaN with facial angle 2.23095 .0192*

Table 1 indicates that the only significant correlation BaS %BaN with mandibular plane .108482 ..05

BaS %BaN with Y-axis .167436 ..05

found with the cranial base angle was the positive corre-

BaS %BaN with interincisal angle 2.26593 .0078*

lation with its two legs and with the proportional length of BaS %BaN with lower incisor to MP .254832 .0109*

the posterior cranial base. In contrast, Table 2 illustrates that BaS %BaN with A-NPg .147829 ..05

the posterior leg had a significant negative correlation with BaS %BaN with A-Perp 2.03689 ..05

the facial angle and B perpendicular and of course a posi- BaS %BaN with B-Perp 2.20278 .0441*

BaS %BaN with BaS/FH .867678 ,.0001*

tive correlation with its proportional linear length to total

BaS %BaN with SN/FH .251986 .0255*

cranial base length. Table 3 indicates that the anterior leg BaS %BaN with treatment time 2.22796 .0297*

only has a significant negative correlation to the Y-axis and

* Statistically significant.

a significant positive correlation to the linear proportional

length of the posterior leg to the total cranial base length.

The linear length of the posterior leg of the cranial base indicated by the lower incisor angulation to the mandibular

had a significant positive correlation with cranial base an- plane and to the mandibular alveolar position in the profile

gle; the posterior cranial base angle to Frankfort horizontal, as well as to the treatment time.

the anterior cranial base angle to Frankfort horizontal, and Table 5 shows whether a difference existed between the

the facial angle are given in Table 4. Although there was proportional lengths of the posterior leg compared with the

no correlation to the maxilla’s position in the profile or in actual linear lengths. A striking contrast existed, with a pos-

the interincisal angle, a significant negative correlation was itive correlation of the proportional length of BaS to the

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 74, No 3, 2004

364 ANDRIA, LEITE, PREVATTE, KING

lower incisor inclination, indicative of an increase in the

incisor angles. An apparent clashing existed with the neg-

ative correlation of the lower incisor inclination on the

mandibular plane to the linear length of BaS, showing a

decrease in the angle. A larger proportional length may be

the result of a longer posterior cranial base to a shorter total

cranial base length as demonstrated by the significant pos-

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article-pdf/74/3/361/1372815/0003-3219(2004)074_0361_cotcba_2_0_co_2.pdf by Colombia user on 09 March 2021

itive correlation of BaSN to SN/FH. A positive correlation

would reduce the length of both the anterior and total cra-

nial base lengths and thereby proportionally increase the

posterior cranial base length. Both the linear and propor-

tional lengths had the same statistically significant negative

correlation to the facial angle, B perpendicular, and treat-

ment time. Both had similar positive significant correlations

to BaS/FH, SN/FH, and BaSN.

DISCUSSION

Frankfort horizontal was selected as the reference plane

in describing the anterior and posterior cranial bases be-

cause of the close physiologic relation between the ear and

the eye as represented by the cephalometric landmarks po-

rion and orbital.30 The variation of the Frankfort plane has

been shown to vary around zero degrees and represents a

horizontal to the earth’s surface.31 The semicircular canals

in the ear and the orbital size change little at an early age

with the downward movement of the maxilla compensated

by deposition on the orbital floor.32 The sense of balance is

intimately related to sight. One only has to observe any

individual attempting to maintain their equilibrium with

their eyes closed. Any change in this relationship during

growth would have adverse effects.

It is wrong to equate the variation of the cranial base FIGURE 4. (A) Cranial base angle. (B) Cranial base angle can be

altered by posterior flexion. (C) Cranial base angle can be altered

angle only to Basion because two legs are present and three

by changes in anterior height. Each variation can affect the mandib-

points of reference (any of which can vary horizontally or ular relation to other facial structures.

vertically) are necessary in the formation of an angle (Fig-

ure 4). The back leg (BaS) of the cranial base angle (BaSN)

may be tipped anteriorly or posteriorly, whereas the front opposite,12–28 where only the total cranial base angle was

leg (SN) may also be tipped up or down anteriorly by a evaluated.

variation in either S or N vertically. Furthermore, variable The statistically negative correlation of SN/FH to the Y-

lengths may compensate for any cranial deflection, eg, an axis implies that a larger anterior cranial base angle would

acute posterior leg that places the mandible forward can produce a more acute Y-axis. The Y-axis has been used as

have this action negated by a long posterior leg that places an indicator of both horizontal and vertical mandibular de-

both Basion and the mandible posteriorly and vice versa. velopment. Yet, no statistical significance is seen when SN/

Initial evaluation of the cranial base angle may be in FH is related to either the facial angle or the mandibular

agreement with previous studies that indicated that the de- plane (Table 3). An additional factor that cannot be ignored

gree of flexure has no effect on the class of malocclusion.1–11 is the position of sella turcica. A lower sella would increase

In contrast the statistically significant negative correlation the anterior cranial base angle and simultaneously reduce

of the posterior cranial base angle to both the facial angle the Y-axis. Once again finding an answer appears to pro-

and B perpendicular would imply that as the angle in- duce another question. The answer may be the statistically

creased, both the skeletal and alveolar components of the significant positive correlation of SN/FH to the proportional

mandible would be located more posteriorly in the face, as length of the posterior cranial base. This corroborates the

seen in the typical Class II division 1 patient. This may suggestion of a lower position of sella. A lower sella would

explain the contrasting findings of the studies indicating the produce a larger cranial base angle, and Table 1 demon-

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 74, No 3, 2004

CORRELATION OF THE CRANIAL BASE AND TREATMENT TIME 365

strates a statistically positive correlation of BaSN to the ment time. The proportional length differed from the linear

proportional length of BaS, whereas a higher nasion would only with an additional negative correlation of the interin-

have no effect on the effective length of BaS. cisal angle and a positive correlation of the lower incisors

The additional factor of linear and proportional lengths angle on the mandibular plane. As the proportional length

of the posterior cranial base may compensate for angular increased, the interincisal angle decreased, whereas the low-

variations. Both the total cranial base and posterior cranial er incisor became more upright to the mandibular plane.

base angles may well be within a one standard deviation

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article-pdf/74/3/361/1372815/0003-3219(2004)074_0361_cotcba_2_0_co_2.pdf by Colombia user on 09 March 2021

range, but the linear and proportional dimensions may vary. REFERENCES

Because the glenoid fossa is located in the posterior cranial

base, an elongated cranial base would bring the glenoid 1. Wilhelm BM, Beck MF, Lidral AC, Vig KWL. A comparison of

fossa back12,22 and the mandible with it. Tables 2 and 4 have cranial base growth in Class I and Class II skeletal patterns. Am

J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:401–405.

almost identical negative significant correlations relating 2. Rothstein T, Phan XL. Dental and facial characteristics and

both the angular and linear posterior cranial base values to growth of females and males with Class II Division 1 malocclu-

the facial angle and the B perpendicular. sion between the ages of 10 and 14 (revisted). Part II. Antero-

The significant negative correlations to treatment time posterior and vertical circumpubertal growth. Am J Orthod Den-

and insignificance with the angular values found in both the tofacial Orthop. 2001;120:542–555.

3. Sandham A, Cheng L. Cranial base and Cleft lip and palate. Angle

linear and proportional posterior cranial base lengths could Orthod. 1988;58:163–168.

be indicative that the linear factors are more influential than 4. Renfroe EW. A study of the facial patterns associated with Class

the angular in predicting the length of treatment time. Ap- I, Class II division 1 and Angle Class I, Class II division 2 mal-

parently treatment time will be reduced when the linear and occlusions. Angle Orthod. 1948;18:12–15.

proportional lengths of the posterior leg are longer. An ob- 5. Guyer EC, Ellis EE, McNamara JA, Behrents RG. Components

of class III malocclusion in juveniles and adolescents. Angle Or-

tuse posterior cranial base angle may, on occasion, have a thod. 1986;56:7–30.

short linear or proportional length, thereby reducing the sig- 6. Battagel JM. The aetiology of Class III malocclusion examined

nificance level of the angular variable. A shorter posterior by tensor analysis. Br J Orthod. 1993;20:283–296.

length in an obtuse posterior cranial base angle would place 7. Varella J. Longitudinal assessment of Class II occlusal and skel-

the glenoid fossa and the condyle at a higher level, possibly etal development in the deciduous dentition. Eur J Orthod. 1993;

15:345.

increasing the mandibular plane angle. This would be ac- 8. Varella J. Early development traits in Class II malocclusion. Acta

companied by a greater vertical component to mandibular Odontol Scand. 1998;56:375–377.

growth and a lesser horizontal component, thereby increas- 9. Dhopatkar A, Bhatia S, Rock P. An investigation into the rela-

ing the treatment time for Class II correction. tionship between the cranial base angle and malocclusion. Angle

Future studies will include any changes that may have Orthod. 2002;72:456–463.

10. Klocke A, Nanda RS, Kahl-Nieke B. Role of cranial base flexure

occurred at the conclusion of treatment and a minimum of in developing sagittal jaw discrepancies. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

two years after removal of all retainers. A possible increase Orthop. 2002;122:386–391.

in the sample size may enable an evaluation of the con- 11. Lewis AB, Roche AF, Wagner B. Pubertal spurts in cranial base

stancy of the saddle angle,33 sex differences,34 sex differ- and mandible: comparisons between individuals. Angle Orthod.

ences during pubescence,35,36 and cranial variation after 1985;55:17–30.

12. Bjork A. Cranial base development. Am J Orthod. 1955;41:198–

treatment and after retention. 225.

13. Hopkin GB, Houston WJB, James GA. The cranial base as an

CONCLUSIONS etiologic factor in malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 1968;38:250–255.

14. Kerr WJS, Hirst D. Craniofacial characteristics of subjects with

The cranial base or saddle angle by itself does not appear normal and post normal occlusions—a longitudinal study. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;92:207–212.

to have any statistical significance to the position of the 15. Kerr WJS, Adams CP. Cranial base and jaw relationships. Am J

chin in the profile, the incisor relationships, the alveolar Anthrop. 1988;77:213–220.

points A and B, or the length of treatment time. The an- 16. Bacon W, Eiller V, Hildwein M, Dubois G. The cranial base in

terior cranial base does not appear to have any statistically subjects with dental and skeletal class II. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:

significant relationship to the position of the chin in the 224–228.

17. Dibetts JMH. Morphological association between the Angle clas-

profile, the mandibular alveolar component, the incisor re-

ses. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:111–118.

lationships, or the length of treatment time. 18. Bacetti T, Antonini A. Glenoid fossa position in different facial

In contrast, the posterior cranial base angle has a statis- types; a cephalometric study. Br J Orthod. 1997;24:55–59.

tically significant negative correlation to both the skeletal 19. Singh GD, McNamara JA, Lozanoff S. Finite element analysis of

facial angle and the alveolar point reflecting a more pos- the cranial base in subjects with class III malocclusion. Br J Or-

thod. 1997;24:103–112.

terior skeletal and alveolar position of the mandible. The

20. Anderson D, Popovich F. Lower cranial base height versus cranial

linear length of BaS demonstrated statistically negative cor- facial dimensions in Angle Class II malocclusions. Angle Orthod.

relations to the facial angle, the alveolar point B, the lower 1983;53:253–260.

incisors angulation on the mandibular plane, and the treat- 21. Anderson D, Popovich F. Relation of cranial base flexure to cra-

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 74, No 3, 2004

366 ANDRIA, LEITE, PREVATTE, KING

nial form and mandibular position. Am J Phys Anthrop. 1983;61: 28. Bjork A. The nature of facial prognathism and its relation to

181–187. normal occlusion of the teeth. Am J Orthod. 1951;37:106–124.

22. Scott JH. Dento-Facial Development and Growth. Oxford: Per- 29. Coben SE. The integration of facial skeletal variants. Am J Or-

gamon Press; 1967. thod. 1955;41:407–434.

23. Rickets RM. Facial and dental changes during orthodontic treat- 30. Ricketts RM, Schullof RJ, Bahga L. Orientation-sella-nasion or

ment as analyzed from the temporomandibular joint. Am J Or- Frankfort horizontal. Am J Orthod. 1976;69:648–654.

thod. 1955;41:407–434. 31. Downs WB. Variations in facial relationships: their significance

24. Moss ML. Correlation of cranial base angulation with cephalic in treatment and prognosis. Am J Orthod. 1948;34:812–840.

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article-pdf/74/3/361/1372815/0003-3219(2004)074_0361_cotcba_2_0_co_2.pdf by Colombia user on 09 March 2021

malformations and growth disharmonies of dental interest. N Y 32. Enlow HE. Handbook of Facial Growth. Philadelphia, Pa: WB

State Dent J. 1955;24:452–454. Saunders Co; 1975.

25. James GA. Cephalometric analysis of 100 Class II div 1 maloc- 33. Lewis AB, Roche AF. Saddle angle: constancy or change? Angle

clusions with special reference to the cranial base. Dent Pract. Orthod. 1977;47:46–53.

1963;14:35–46. 34. Roche AF, Lewis AB. Sex differences in the elongation of the

26. Houston WJB. A cephalometric analysis of Angle Class II div 2 cranial base during pubescence. Angle Orthod. 1974;44:279–294.

malocclusion in mixed dentition. Dent Pract. 1967;17:372–376. 35. Lewis AB, Roche AF. Cranial base elongation in boys during

27. Kerr WJS, Hirst D. Craniofacial characteristics of subjects with pubescence. Angle Orthod. 1974;44:83–93.

normal and postnormal occlusions—a longitudinal study. Am J 36. Lewis AB, Roche AF. Cranial base elongation in girls during

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;92:207–212. pubescence. Angle Orthod. 1972;42:358–367.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 74, No 3, 2004

You might also like

- Slow Pal at Al ExpansionDocument6 pagesSlow Pal at Al ExpansionAndrea Cárdenas Sandoval100% (1)

- Occlusal Plane Alteration in Orthognathic Surgery - Wolford1993Document11 pagesOcclusal Plane Alteration in Orthognathic Surgery - Wolford1993Andrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Tooth MovementDocument10 pagesThree-Dimensional Evaluation of Tooth MovementAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3 AssesmentDocument6 pagesArticulo 3 AssesmentAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Articulo 2Document20 pagesArticulo 2Andrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Cjaa 028Document6 pagesCjaa 028Andrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Sarver Mission PossibleDocument13 pagesSarver Mission PossibleAndrea Cárdenas Sandoval100% (1)

- 2006, Huang, Evaluación de PICO Como Representación Del Conocimiento para Preguntas ClínicasDocument5 pages2006, Huang, Evaluación de PICO Como Representación Del Conocimiento para Preguntas ClínicasAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Articulo InformDocument9 pagesArticulo InformAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Orthognathic Surgery in COVID-19 Times, Is It Safe?Document4 pagesOrthognathic Surgery in COVID-19 Times, Is It Safe?Andrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Reliability of Natural Head Position in Orthodontic Diagnosis: A Cephalometric StudyDocument4 pagesReliability of Natural Head Position in Orthodontic Diagnosis: A Cephalometric StudyAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Basic and Advanced Operative Techniques in Orthognatic SurgeryDocument23 pagesBasic and Advanced Operative Techniques in Orthognatic SurgeryAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Assessment of Orthognathic Information ClinicDocument5 pagesIntroduction and Assessment of Orthognathic Information ClinicAndrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- O Dfen 2012153 P 302Document24 pagesO Dfen 2012153 P 302Andrea Cárdenas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Wps Gtaw Monel b127 b164Document2 pagesWps Gtaw Monel b127 b164Srinivasan Muruganantham67% (3)

- Method Statement For Painting WorksDocument2 pagesMethod Statement For Painting Worksmustafa100% (3)

- Block-1 BLIS-03 Unit-2 PDFDocument15 pagesBlock-1 BLIS-03 Unit-2 PDFravinderreddynNo ratings yet

- Study Antimicrobial Activity of Lemon (Citrus Lemon L.) Peel ExtractDocument5 pagesStudy Antimicrobial Activity of Lemon (Citrus Lemon L.) Peel ExtractLoredana Veronica ZalischiNo ratings yet

- Sunfix Blue SPRDocument7 pagesSunfix Blue SPRDyeing 2 Wintex100% (2)

- Questionpaper Unit1WCH01 January2018 IAL Edexcel ChemistryDocument24 pagesQuestionpaper Unit1WCH01 January2018 IAL Edexcel Chemistryshawon.sbd06No ratings yet

- Origami Undergrad ThesisDocument63 pagesOrigami Undergrad ThesisEduardo MullerNo ratings yet

- NumerologieDocument22 pagesNumerologieJared Powell100% (1)

- WEG CTM Dwb400 10004024165 Installation Guide EnglishDocument1 pageWEG CTM Dwb400 10004024165 Installation Guide Englishjeffv65No ratings yet

- Tas 5731Document60 pagesTas 5731charly36No ratings yet

- Staff Code Subject Code Subject Data FromDocument36 pagesStaff Code Subject Code Subject Data FromPooja PathakNo ratings yet

- Time Series - Practical ExercisesDocument9 pagesTime Series - Practical ExercisesJobayer Islam TunanNo ratings yet

- Despiesse de Las Guallas D6H SERIE 3ZF06342Document4 pagesDespiesse de Las Guallas D6H SERIE 3ZF06342David manjarresNo ratings yet

- Msds - Lemon Detergent Acco BrandsDocument10 pagesMsds - Lemon Detergent Acco Brandsfitri widyaNo ratings yet

- API 571 Quick ReviewDocument32 pagesAPI 571 Quick ReviewMahmoud Hagag100% (1)

- A General Strategy For The Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based CompositesDocument8 pagesA General Strategy For The Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based CompositesCristian Gonzáles OlórteguiNo ratings yet

- ECE 374 - Part - 1c - S2017Document37 pagesECE 374 - Part - 1c - S2017Zakaria ElwalilyNo ratings yet

- A Review of Linear AlgebraDocument19 pagesA Review of Linear AlgebraOsman Abdul-MuminNo ratings yet

- Jerms B 2109 - 0BDocument10 pagesJerms B 2109 - 0BNothing is ImpossibleNo ratings yet

- Oertel - Extracts From The Jāiminīya-Brāhma A and Upanishad-Brāhma A, Parallel To Passages of TheDocument20 pagesOertel - Extracts From The Jāiminīya-Brāhma A and Upanishad-Brāhma A, Parallel To Passages of Thespongebob2812No ratings yet

- 18-039 Eia 07Document34 pages18-039 Eia 07sathishNo ratings yet

- Squares and Square Roots Chapter Class ViiiDocument24 pagesSquares and Square Roots Chapter Class ViiiManas Hooda100% (1)

- MC 1Document109 pagesMC 1ricogamingNo ratings yet

- Engineering Drawings and Plans: Engr. Rolly S. TambeDocument4 pagesEngineering Drawings and Plans: Engr. Rolly S. TambeFred Joseph G. AlacayanNo ratings yet

- FlazasulfuronDocument2 pagesFlazasulfuronFenologiaVinhaNo ratings yet

- Food ProductionDocument106 pagesFood ProductionAna Marie100% (1)

- Big Fat Lies - How The Diet Industry Is Making You Sick, Fat & PoorDocument212 pagesBig Fat Lies - How The Diet Industry Is Making You Sick, Fat & PoorangelobuffaloNo ratings yet

- Nanotechnology ApplicationsDocument11 pagesNanotechnology ApplicationsDivya DivyachilaNo ratings yet

- BFE II ScenariosDocument25 pagesBFE II Scenarioselmitxel100% (1)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science IiiDocument3 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Science Iiicharito riveraNo ratings yet