Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Maia Et Al. 2011 Xenodon Neuwiedi Diet

Uploaded by

Thiago Maia CarneiroCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Maia Et Al. 2011 Xenodon Neuwiedi Diet

Uploaded by

Thiago Maia CarneiroCopyright:

Available Formats

Natural History Notes 447

Of particular interest is the position of the snake along the

PHOTO BY M. Wachlevski

stick (Fig. 1). It was motionless and oriented head-down in a

position similar to that often described as ambush posture for

some arboreal snake species (e.g., Corallus spp., Henderson

2002. Neotropical Treeboas. Krieger Publ. Co., Malabar, Florida.

197 pp.). The snake was found after several hours of rain beside

a dry riverbed and we suspect that it was using the stick perch

as a vantage point from which to scan for snails and slugs mov-

ing in the damp leaf litter below. Preliminary data from a feeding

behavior study led by CMS support this hypothesis in that cap-

tive T. philippii often use visual cues to initially locate and follow

molluscan prey.

We thank J. A. Campbell for assistance, and G. N. Weather-

man for assistance with field work. The National Science Foun-

dation (DEB-0613802) provided financial support.

COLEMAN M. SHEEHY III (e-mail: cmsheehy@uta.edu), JEFFREY W.

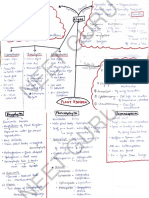

STREICHER, CHRISTIAN L. COX, and JACOBO REYES-VELASCO, Amphib- Fig. 1. An adult female Xenodon neuwiedii found preying on a Rhi-

ian and Reptile Diversity Research Center, Department of Biology, Univer- nella abei in the Parque Estadual da Serra do Tabuleiro, Brazil.

sity of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, Texas 76019, USA.

Holos, Ribeirão Preto; Sazima and Haddad 1992. In Morellato

TROPIDONOPHIS DORIAE (Barred Keelback). ENDOPARA- [ed.], História Natural da Serra do Japi: Ecologia e Preservação

SITES. Tropidonophis doriae is known from Indonesia (Irian, de uma Área Florestal no Sudeste do Brasil, pp. 212–236. FAPESP,

Java, Aru Islands) and Papua New Guinea (Malnate and Under- Campinas). However, anurans belonging to other families (Hy-

wood 1988. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia 140:59–201). It is a lidae, Leptodactylidae, and Cyclorhamphidae) and even lizards

terrestrial, nocturnal predator that eats frogs and fish (Malnate (Enyalius sp.) are occasionally consumed (Hartmann et al. 2009.

and Underwood, op. cit). To our knowledge there are no reports Biota Neotrop. 9:173–184; Marques and Sazima, op. cit.). Rhinel-

of helminths for T. doriae. The purpose of this note is to estab- la abei is a frog distributed in the southern Atlantic Rainforest

lish an initial helminth list for T. doriae. Two T. doriae from the from Paraná state to southern Santa Catarina state and northern

herpetology collection of the Bishop Museum (BPBM), Hono- areas of Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil (Baldissera Jr. et al. 2004.

lulu, HI, USA each had nematodes protruding from a slit in their Arq. Mus. Nac., Rio de Janeiro 62[3]:255–282). Here we report the

body walls (BPBM 31526, SVL = 254 mm; BPBM 31527, SVL = predation of the frog R. abei by the snake X. neuwiedii.

327 mm). Both snakes were collected on 3 April 2007 in Madang On 16 January 2009, in the Parque Estadual da Serra do Tabu-

Province, Wanang, Papua New Guinea (5.232118°S, 145.18068°E; leiro, Santo Amaro da Imperatriz municipality, Santa Catarina

datum: WGS84; elev. 600 m). Nematodes were removed, cleared state, Brazil (27.7427°S, 48.8075°W, datum: SAD 69), an adult fe-

in glycerol, placed on glass slides, coverslipped, studied under male X. neuwiedii (SVL = 489 mm; tail length = 113 mm; 59.5 g),

a compound microscope and identified as Tanqua anomala was found at 1015 h on leaf litter in an area of dense ombrophi-

(eight from BPBM 31526) and (six from BPBM 31527). Voucher lous forest ingesting an adult R. abei (SVL = 69.1 mm; 26.2 g; 44%

helminths were deposited in the United States National Para- of the snake’s mass). The frog was being ingested headfirst, ven-

site Collection (USNPC), Beltsville, Maryland, USA as USNPC tral side up, and was still alive (Fig. 1). Manipulation of the snake

(103501) and the Bishop Museum (BPBM) as (H423). Tanqua resulted in the release of the prey, which presented deep wounds

anomala is common in snakes from southeast and southern Asia in the abdominal region. Batracophagy seems to be the most fre-

(Baker 1987. Occas. Pap. Mem. Univ. Newfoundland 11:1–327; quent feeding habit of Xenodon (Marques et al. 2001. Serpentes

Sood 1999. Reptilian Nematodes from South Asia, International da Mata Atlântica. Guia Ilustrado para a Serra do Mar. Ribeirão

Book Distributors, Dehra Dun, India. 299 pp.). There is a record Preto, Editora Holos. 184 pp.) and some species have special-

of a larval T. anomala in Hoplobatrachus tigerinus (= Rana tig- ized skulls and dentition, facilitating the capture and ingestion

rina) in Baker (op. cit). As T. doriae feeds on frogs, frogs may act of frogs (Kardong 1979. Evolution 33:433–443). The wounds we

as paratenic (= transport hosts) for T. anomala. Tanqua anomala observed are evidence of the functionality of X. neuwiedii’s en-

in T. doriae is a new host record. Papua New Guinea is a new lo- larged posterior teeth, which allow perforation of the prey and

cality record. the consequent evacuation of air, which is accumulated in the

We thank Pumehana Imada (IBPBM) for facilitating our ex- toad’s body for defense (Amaral 1978. Serpentes do Brasil, Icono-

amination of T. doriae. grafia Colorida, 2a edição. Melhoramentos/EDUSP, São Paulo.

STEPHEN R. GOLDBERG, Whittier College, Department of Biology, PO 247 pp.).

Box 634, Whittier, California 90608, USA (e-mail: sgoldberg@whittier.edu); THIAGO MAIA (e-mail: thiagomaianc@gmail.com), MILENA

CHARLES R. BURSEY, Pennsylvania State University, Shenango Campus, WACHLEVSKI (e-mail: milenawm@yahoo.com), LUCIANA BARÇANTE (e-

Department of Biology, Sharon, Pennsylvania 16146, USA (e-mail: cxb13@ mail: lubarcante@hotmail.com), and CARLOS F. D. ROCHA (e-mail: cfdro-

psu.edu). cha@uerj.br), Departamento de Ecologia, Universidade do Estado do Rio

de Janeiro, Rua São Francisco Xavier 524, CEP 20550-013, Rio de Janeiro,

XENODON NEUWIEDII (False Lancehead). DIET. The dipsadid Brazil.

snake Xenodon neuwiedii has a diet composed predominantly

of anurans, especially those in the genus Rhinella (Marques and

Sazima 2004. In Marques and Duleba [eds.], Estação Ccológica

Juréia-Itatins: Ambiente Físico, Flora e Fauna, pp. 257–277.

Herpetological Review 42(3), 2011

You might also like

- NATURAL PREDATORDocument2 pagesNATURAL PREDATORlaspiur22blues7327No ratings yet

- Reproduction of Rough Coffee Snake and Diet of Patagonian RacerDocument2 pagesReproduction of Rough Coffee Snake and Diet of Patagonian RacerArco Iris CallejaNo ratings yet

- Morato Et Al Paleosuchus Trigonatus Diet Movements Herpetol. Bull. 2011Document2 pagesMorato Et Al Paleosuchus Trigonatus Diet Movements Herpetol. Bull. 2011Sérgio Augusto Abrahão MoratoNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument3 pages1 PBYeison Calizaya MeloNo ratings yet

- BothropsDocument3 pagesBothropsYostin AñinoNo ratings yet

- Morato - 2011 - Bothropoides Jararaca Prey - Herp - ReviewDocument2 pagesMorato - 2011 - Bothropoides Jararaca Prey - Herp - ReviewSérgio Augusto Abrahão MoratoNo ratings yet

- Philodryas Patagoniensis - Diet - Lopez (2003)Document2 pagesPhilodryas Patagoniensis - Diet - Lopez (2003)Danilo CapelaNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Prey Item For The Yellow Tail Cribo Drymarchon Corais Boie 1827, in The Brazilian SavannahDocument4 pagesAn Unusual Prey Item For The Yellow Tail Cribo Drymarchon Corais Boie 1827, in The Brazilian SavannahcomandocrawNo ratings yet

- Predation On Hypsiboas Bischoffi (Anura Hylidae) by Phoneutria Nigriventer (Araneae Ctenidae) in Southern BrazilDocument2 pagesPredation On Hypsiboas Bischoffi (Anura Hylidae) by Phoneutria Nigriventer (Araneae Ctenidae) in Southern BrazilNathalie FoersterNo ratings yet

- Sales Et Al 2010 - Cnemidophorus Ocellifer - CannibalismDocument2 pagesSales Et Al 2010 - Cnemidophorus Ocellifer - CannibalismRaul SalesNo ratings yet

- HR482NaturalHistory407 459Document53 pagesHR482NaturalHistory407 459dfdfNo ratings yet

- CONICET Digital Nro. ADocument1 pageCONICET Digital Nro. ADescargaryaNo ratings yet

- Martins Etal Final1Document3 pagesMartins Etal Final1Ana Karolina MorenoNo ratings yet

- Natural History Notes on Diet and Combat Behavior of SnakesDocument1 pageNatural History Notes on Diet and Combat Behavior of SnakesDanilo CapelaNo ratings yet

- CheckList Article 53857 en 1Document4 pagesCheckList Article 53857 en 1Jonathan DigmaNo ratings yet

- Hypsiboas Punctatus: Distribution Extension and Filling: Check List 2006Document2 pagesHypsiboas Punctatus: Distribution Extension and Filling: Check List 2006Sebas CirignoliNo ratings yet

- Tadpole, Oophagy, Advertisement Call, and Geographic Distribution of Aparasphenodon Arapapa Pimenta, Napoli and Haddad 2009 (Anura, Hylidae)Document6 pagesTadpole, Oophagy, Advertisement Call, and Geographic Distribution of Aparasphenodon Arapapa Pimenta, Napoli and Haddad 2009 (Anura, Hylidae)Guilherme SousaNo ratings yet

- Linares Et Al. 2016 - (First Report On Predation of Adult Anurans by Odonata Larvae)Document3 pagesLinares Et Al. 2016 - (First Report On Predation of Adult Anurans by Odonata Larvae)Antônio LinaresNo ratings yet

- Reptile Cleaning MutualismDocument3 pagesReptile Cleaning MutualismUber SchalkeNo ratings yet

- Distribution, Behavior, and Conservation Status of The Rufous Twistwing (Cnipodectes Superrufus)Document12 pagesDistribution, Behavior, and Conservation Status of The Rufous Twistwing (Cnipodectes Superrufus)api-19973082No ratings yet

- Guilherme - & - Dantas - 2008Document2 pagesGuilherme - & - Dantas - 2008api-19973082No ratings yet

- Rhinella Major Rhinella GR Margaritifera Food For SpidersDocument7 pagesRhinella Major Rhinella GR Margaritifera Food For SpidersPatrick SanchesNo ratings yet

- New Distributional Records of Amphibians in The Andes of EcuadorDocument2 pagesNew Distributional Records of Amphibians in The Andes of EcuadorOreomanesNo ratings yet

- NATURAL HISTORY NOTES: CROCODYLIAN PREYS ON PORCUPINEDocument26 pagesNATURAL HISTORY NOTES: CROCODYLIAN PREYS ON PORCUPINEArlene NavaNo ratings yet

- Helicop Angulatus PDFDocument2 pagesHelicop Angulatus PDFChantal AranNo ratings yet

- Helicops Leopardinus: Distribution Extension,: Notes On Geographic DistributionDocument2 pagesHelicops Leopardinus: Distribution Extension,: Notes On Geographic DistributionChantal AranNo ratings yet

- Daphnia Lumholtzi ZANATA Et Al 2003Document4 pagesDaphnia Lumholtzi ZANATA Et Al 2003Higor LessaNo ratings yet

- A New Cretaceous Thyreophoran From Patagonia Supports A South American Lineage of Armoured DinosaursDocument12 pagesA New Cretaceous Thyreophoran From Patagonia Supports A South American Lineage of Armoured DinosaursDino ManiacNo ratings yet

- Organisms Diversity & Evolution: Systematic Revision of the Brown Vine SnakeDocument24 pagesOrganisms Diversity & Evolution: Systematic Revision of the Brown Vine SnakeRicardo SozaNo ratings yet

- Chavez Et Al 2010 CophosaurusDocument1 pageChavez Et Al 2010 CophosaurusJero ChávezNo ratings yet

- Check List: Bivalves and Gastropods of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, PhilippinesDocument12 pagesCheck List: Bivalves and Gastropods of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, PhilippinesMarc AlexandreNo ratings yet

- Snake Copulation Observation Provides Insights into Reproductive Behavior of Threatened West Indian SpeciesDocument2 pagesSnake Copulation Observation Provides Insights into Reproductive Behavior of Threatened West Indian Specieslaspiur22blues7327No ratings yet

- Supérvivencia y LogebidadDocument10 pagesSupérvivencia y LogebidadDaniel VargasNo ratings yet

- Dendropsophus Melanargyreus - Predation by Ancylometes Rufus - Moura & Azevedo (2011)Document3 pagesDendropsophus Melanargyreus - Predation by Ancylometes Rufus - Moura & Azevedo (2011)Mario MouraNo ratings yet

- HR Dec 2022 Full 150dpi NaturalHistoryNotes-42Document1 pageHR Dec 2022 Full 150dpi NaturalHistoryNotes-42Thairis Telli PimentelNo ratings yet

- Dendrelaphis Schokari (Schokar's Bronzeback) - PredationDocument31 pagesDendrelaphis Schokari (Schokar's Bronzeback) - PredationH.Krishantha Sameera de ZoysaNo ratings yet

- Laspiur & Acosta-LIOLAEMUS INACAYALI-Maximum Size-2008Document1 pageLaspiur & Acosta-LIOLAEMUS INACAYALI-Maximum Size-2008laspiursaurusNo ratings yet

- Predation of lizards by Attila spadiceus and Gekko horsfieldii by Sitta frontalisDocument2 pagesPredation of lizards by Attila spadiceus and Gekko horsfieldii by Sitta frontalisvanessa e bruno becaciciNo ratings yet

- Oxyrhopus Petola MatingDocument2 pagesOxyrhopus Petola MatingDaniel SimõesNo ratings yet

- Altitudinal Distribution of Skinks Along Cantubias Ridge of Mt. Pangasugan, Baybay, LeyteDocument20 pagesAltitudinal Distribution of Skinks Along Cantubias Ridge of Mt. Pangasugan, Baybay, LeyteLitlen DaparNo ratings yet

- HB11 - 2022 - 2 - Carvalho - Rhinella PredationDocument7 pagesHB11 - 2022 - 2 - Carvalho - Rhinella PredationWagner M. S. SampaioNo ratings yet

- Snake Death After Failed Lizard PredationDocument3 pagesSnake Death After Failed Lizard PredationAlexander RochaNo ratings yet

- Reproductive Biology of A Bromeligenous Frog Endemic To The Atlantic ForestDocument14 pagesReproductive Biology of A Bromeligenous Frog Endemic To The Atlantic ForestamandasantiagoNo ratings yet

- Lizards, Snakes, and Amphisbaenians From The Quaternary Sand Dunes of The Middle Rio Sao Francisco, Bahia, BrazilDocument12 pagesLizards, Snakes, and Amphisbaenians From The Quaternary Sand Dunes of The Middle Rio Sao Francisco, Bahia, Braziluseparadown downNo ratings yet

- Elephant Dung - EcosystemDocument2 pagesElephant Dung - EcosystemmeshikaNo ratings yet

- New Material of Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) From The Pleistocene of Southern BrazilDocument12 pagesNew Material of Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) From The Pleistocene of Southern BrazilCebolácio MenezesNo ratings yet

- Check List: New Locality Records of Rhagomys Longilingua Luna & Patterson, 2003 (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in PeruDocument7 pagesCheck List: New Locality Records of Rhagomys Longilingua Luna & Patterson, 2003 (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in PeruMiluska R. SànchezNo ratings yet

- Bernardo - 2012 - Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Reserva BiológicaDocument9 pagesBernardo - 2012 - Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Reserva BiológicaIsla MarialvaNo ratings yet

- First Record of Stenochrus Portoricensis Chamberlin, 1922 (Arachnida: Schizomida: Hubbardiidae) For The Pernambuco State, BrazilDocument2 pagesFirst Record of Stenochrus Portoricensis Chamberlin, 1922 (Arachnida: Schizomida: Hubbardiidae) For The Pernambuco State, BrazilAndré LiraNo ratings yet

- A New Genus of Long-Horned CaddisflyDocument17 pagesA New Genus of Long-Horned CaddisflyCarli RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Dias Et Al - Trachycephalus NigromaculatusDocument2 pagesDias Et Al - Trachycephalus NigromaculatusIuri Ribeiro DiasNo ratings yet

- Airaldi Et Al 2009Document3 pagesAiraldi Et Al 2009Katia AWNo ratings yet

- New Sponge Species from Atlantic OceanDocument7 pagesNew Sponge Species from Atlantic OceanMara Paola DurangoNo ratings yet

- Amphibians and Reptiles of La Selva, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean Slope: A Comprehensive GuideFrom EverandAmphibians and Reptiles of La Selva, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean Slope: A Comprehensive GuideRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Revision of South American Freshwater Copepod GenusDocument22 pagesRevision of South American Freshwater Copepod GenuspcorgoNo ratings yet

- Shark Teeth From The Pirabas Formation LDocument10 pagesShark Teeth From The Pirabas Formation LGiovanni GalliNo ratings yet

- Comparative Morphometry and Biogeography of The Freshwater Turtles of Genus Pangshura Testudines Geoemydidae PangshuraDocument17 pagesComparative Morphometry and Biogeography of The Freshwater Turtles of Genus Pangshura Testudines Geoemydidae Pangshuranirupamabhol1980No ratings yet

- Currylowetal 2015bDocument4 pagesCurrylowetal 2015bvenicaveniceNo ratings yet

- Bones Paternes CaracaraDocument9 pagesBones Paternes Caracarasilviahfestamagica1No ratings yet

- The Fruit Fly Fauna (Diptera : Tephritidae : Dacinae) of Papua New Guinea, Indonesian Papua, Associated Islands and BougainvilleFrom EverandThe Fruit Fly Fauna (Diptera : Tephritidae : Dacinae) of Papua New Guinea, Indonesian Papua, Associated Islands and BougainvilleNo ratings yet

- Maia Et Al. 2011 Diet of The Lizard Ecpleopus GaudichaudiiDocument6 pagesMaia Et Al. 2011 Diet of The Lizard Ecpleopus GaudichaudiiThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Cox Et Al. 2004 - Amazon Forest Dieback Under Climate-Carbon Cycle Projections For The 21st CenturyDocument20 pagesCox Et Al. 2004 - Amazon Forest Dieback Under Climate-Carbon Cycle Projections For The 21st CenturyThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Cox Et Al. 2013 - Sensitivity of Tropical Carbon To Climate Change Constrained by Variability of CO2Document5 pagesCox Et Al. 2013 - Sensitivity of Tropical Carbon To Climate Change Constrained by Variability of CO2Thiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Fearnside 2001 - The Potential of Brazils Forest For Mitigating Global WrmingDocument18 pagesFearnside 2001 - The Potential of Brazils Forest For Mitigating Global WrmingThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Telles Et Al. 2012 - Anurans From The Restinga of The Parque Natural Municipal de GrumariDocument7 pagesTelles Et Al. 2012 - Anurans From The Restinga of The Parque Natural Municipal de GrumariThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2017 - Body Size, Wind Intensity and Thermal Sources of Liolaemus PDFDocument4 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2017 - Body Size, Wind Intensity and Thermal Sources of Liolaemus PDFThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Predation of Crossodactylus Gaucichaudii by Bothrops JararacussuDocument1 pageMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Predation of Crossodactylus Gaucichaudii by Bothrops JararacussuThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- High prevalence of chigger mites on coastal lizard populationsDocument7 pagesHigh prevalence of chigger mites on coastal lizard populationsThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- 2016 Book PhilosophyOfScienceForScientis PDFDocument263 pages2016 Book PhilosophyOfScienceForScientis PDFGkcukNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Thermoregulation and Daily Activity of Mabuya MacrorhynchaDocument5 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Thermoregulation and Daily Activity of Mabuya MacrorhynchaThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Defensive Behaviors of Tropidurus CatalanensisDocument4 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Defensive Behaviors of Tropidurus CatalanensisThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Helminth Infections in Sympatric Tropidurus Hispidus and T. Semitaeniatus PDFDocument8 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Helminth Infections in Sympatric Tropidurus Hispidus and T. Semitaeniatus PDFThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Cannibalism in Tropidurus HispidusDocument1 pageMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Cannibalism in Tropidurus HispidusThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- 850 NATURAL HISTORY NOTES ON KEYAUDIA GUADIACHAUDIIDocument1 page850 NATURAL HISTORY NOTES ON KEYAUDIA GUADIACHAUDIIThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Bone Deformities in Tropidurus CatalanensisDocument1 pageMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Bone Deformities in Tropidurus CatalanensisThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Diverging temporal and thermal niches favor syntopy of lizard speciesDocument14 pagesDiverging temporal and thermal niches favor syntopy of lizard speciesThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Biology of The Integument 1986Document870 pagesBiology of The Integument 1986Thiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Clutch and Egg Sizes of Tropidurus CatalanensisDocument2 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Clutch and Egg Sizes of Tropidurus CatalanensisThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro & Rocha 2020 - Cloacal Discharge in Tropidurus Hispidus and Tropidurus SemitaeniatusDocument2 pagesMaia-Carneiro & Rocha 2020 - Cloacal Discharge in Tropidurus Hispidus and Tropidurus SemitaeniatusThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro & Maia-Solidade 2020 - Climbing Behavior of Rhinella IctericaDocument3 pagesMaia-Carneiro & Maia-Solidade 2020 - Climbing Behavior of Rhinella IctericaThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Bone Deformities in Tropidurus CatalanensisDocument1 pageMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2020 - Bone Deformities in Tropidurus CatalanensisThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Thermoregulation and Daily Activity of Mabuya MacrorhynchaDocument5 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Thermoregulation and Daily Activity of Mabuya MacrorhynchaThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- 2 Chapin Principles of Terrestrial EcologyDocument537 pages2 Chapin Principles of Terrestrial EcologyValeriaAndrea100% (1)

- (Graduate Texts in Physics) Massimiliano Bonamente (Auth.) - Statistics and Analysis of Scientific Data-Springer-Verlag New York (2017)Document323 pages(Graduate Texts in Physics) Massimiliano Bonamente (Auth.) - Statistics and Analysis of Scientific Data-Springer-Verlag New York (2017)HernánQuiroz100% (1)

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2017 - Body Size, Wind Intensity and Thermal Sources of Liolaemus PDFDocument4 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2017 - Body Size, Wind Intensity and Thermal Sources of Liolaemus PDFThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Helminth Infections in Sympatric Tropidurus Hispidus and T. Semitaeniatus PDFDocument8 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2018 - Helminth Infections in Sympatric Tropidurus Hispidus and T. Semitaeniatus PDFThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- 2 Chapin Principles of Terrestrial EcologyDocument537 pages2 Chapin Principles of Terrestrial EcologyValeriaAndrea100% (1)

- Maia-Carneiro Et Al. 2017 - Trophic Niche of Tropidurus Lizards PDFDocument8 pagesMaia-Carneiro Et Al. 2017 - Trophic Niche of Tropidurus Lizards PDFThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Predation of Tropidurus lizard by snakeDocument4 pagesPredation of Tropidurus lizard by snakeThiago Maia CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Evolution of the Sporophyte – Telome TheoryDocument34 pagesEvolution of the Sporophyte – Telome Theoryjeline raniNo ratings yet

- Soal UKK B Inggris Kelas 7-1Document6 pagesSoal UKK B Inggris Kelas 7-1Alvania Diva KiranaNo ratings yet

- Informative Speech 1 - The Possible Dangers of GMO'sDocument4 pagesInformative Speech 1 - The Possible Dangers of GMO'schilliyimani100% (2)

- Lesson 3: Flow of EnergyDocument3 pagesLesson 3: Flow of EnergyCanapi AmerahNo ratings yet

- Questions: Energy Flow PyramidsDocument3 pagesQuestions: Energy Flow PyramidsDaniela Duran100% (3)

- Cloning Human BeingsDocument310 pagesCloning Human BeingsThe Hastings CenterNo ratings yet

- Common Characteristics of Myxomycetes (Slime Molds)Document3 pagesCommon Characteristics of Myxomycetes (Slime Molds)Tài nguyễnNo ratings yet

- BryoDocument2 pagesBryoAnonymous RbkgTBn1K3No ratings yet

- 2013 249tr Epigenetic Differences After Prenatal Adversity The Dutch Hunger WinterDocument249 pages2013 249tr Epigenetic Differences After Prenatal Adversity The Dutch Hunger WinterNguyễn Tiến HồngNo ratings yet

- Differences between Virus, Viroid, Phytoplasma, Spiroplasma and Satellite ElementsDocument10 pagesDifferences between Virus, Viroid, Phytoplasma, Spiroplasma and Satellite ElementsMuhammad AzamNo ratings yet

- FOOD CHAINS AND FOOD WEBS EXPLAINEDDocument34 pagesFOOD CHAINS AND FOOD WEBS EXPLAINEDrevinrubyNo ratings yet

- Biology Project On AlgaeDocument19 pagesBiology Project On AlgaeKgp Nampoothiri100% (6)

- Characteristics of Living OrganismsDocument21 pagesCharacteristics of Living OrganismsSamaira JainNo ratings yet

- Teaworld - Kkhsou.in-Shade and Shade Management in Tea in NE IndiaDocument2 pagesTeaworld - Kkhsou.in-Shade and Shade Management in Tea in NE IndiaDebasish RazNo ratings yet

- Arthropod ClassificationDocument6 pagesArthropod ClassificationArmaan AliNo ratings yet

- Chromocult Coliform Agar - AOAC Cert 2022 PDFDocument5 pagesChromocult Coliform Agar - AOAC Cert 2022 PDFBurasras BurasrasNo ratings yet

- (Elephas Maximus) During The First Wet Season at TheDocument44 pages(Elephas Maximus) During The First Wet Season at TheAvinash Krishnan100% (1)

- Swarnamalini Kathirvel (U3193222) :::: Patient Age / Sex 24 Y / Female BranchDocument1 pageSwarnamalini Kathirvel (U3193222) :::: Patient Age / Sex 24 Y / Female BranchswarnamaliniNo ratings yet

- ScienceworldDocument3 pagesScienceworldapi-559454391No ratings yet

- Soal FormatifDocument3 pagesSoal FormatifNurul Hilda IlyasNo ratings yet

- The Last Tree On EarthDocument1 pageThe Last Tree On EarthJaycee Badiola BacoNo ratings yet

- Csi Africa: Tracking Ivory Poachers: Teacher Guide To ActivityDocument5 pagesCsi Africa: Tracking Ivory Poachers: Teacher Guide To Activitybunser animationNo ratings yet

- Plant Reproduction, Genetics, and DigestionDocument2 pagesPlant Reproduction, Genetics, and DigestionKint MackeyNo ratings yet

- Mapping of Significant Natural Resources: Category: Animals (Fauna)Document4 pagesMapping of Significant Natural Resources: Category: Animals (Fauna)Dei HernandezNo ratings yet

- Genetics Questions To PrepareDocument6 pagesGenetics Questions To PrepareJohn Osborne100% (1)

- Lorenzo's Oil Movie ReactionDocument4 pagesLorenzo's Oil Movie Reactionharley olzanskiNo ratings yet

- Algal BloomsDocument3 pagesAlgal BloomsAroma MangaoangNo ratings yet

- A.P. Biology Chapter 35 Test ReviewDocument8 pagesA.P. Biology Chapter 35 Test ReviewAJ JonesNo ratings yet

- Fungal Infections Explained: Types, Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentsDocument19 pagesFungal Infections Explained: Types, Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentsKasuganti koteshwar raoNo ratings yet

- S07 Genetic fragmentation and sexual reproduction in algaeDocument3 pagesS07 Genetic fragmentation and sexual reproduction in algaedamelo7932No ratings yet