Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Suicide Ideation and Attempts in A Pediatric Emergency Department Before and During COVID-19

Uploaded by

mikoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Suicide Ideation and Attempts in A Pediatric Emergency Department Before and During COVID-19

Uploaded by

mikoCopyright:

Available Formats

Suicide Ideation and Attempts in

a Pediatric Emergency Department

Before and During COVID-19

Ryan M. Hill, PhD,a Katrina Rufino, PhD,b,c Sherin Kurian, MD,d Johanna Saxena, BS, BA,d Kirti Saxena, MD,d Laurel Williams, DOd

Elevated rates of mental health concerns have been identified during the

OBJECTIVES: abstract

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In this study, we sought to evaluate whether

youth reported a greater frequency of suicide-related behaviors during the 2020 COVID-19

pandemic as compared with 2019. We hypothesized that rates of suicide-related behaviors

would be elevated between the months of March and July 2020 as compared with 2019,

corresponding to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS: Routine

suicide-risk screening was completed with youth aged 11 to 21 in a pediatric

emergency department. Electronic health records data for suicide-risk screens completed

between January and July 2019 and January and July 2020 were evaluated. A total of 9092

completed screens were examined (mean age 14.72 years, 47.7% Hispanic and/or Latinx,

26.7% non-Hispanic white, 18.7% non-Hispanic Black).

RESULTS: Rates of positive suicide-risk screen results from January to July 2020 were compared

with corresponding rates from January to July 2019. Results indicated a significantly higher

rate of suicide ideation in March and July 2020 and higher rates of suicide attempts in

February, March, April, and July 2020 as compared with the same months in 2019.

CONCLUSIONS: Rates of suicide ideation and attempts were higher during some months of 2020 as

compared with 2019 but were not universally higher across this period. Months with

significantly higher rates of suicide-related behaviors appear to correspond to times when

COVID-19–related stressors and community responses were heightened, indicating that youth

experienced elevated distress during these periods.

Departments of aPediatrics and dPsychiatry, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; bDepartment of Social WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Despite prominent

Sciences, University of Houston–Downtown, Houston, Texas; and cThe Menninger Clinic, Houston, Texas attention to the potential mental health consequences

of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related

Dr Hill conceptualized and conducted the analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the

manuscript; Drs Kurian, K. Saxena, Rufino, and Williams and Ms J. Saxena reviewed and revised the

stressors, to date, few data have revealed increased

manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be rates of suicide-related behaviors among youth during

accountable for all aspects of the work. the COVID-19 pandemic.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-029280 WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: In this study, we identified

Accepted for publication Dec 10, 2020 increased rates of youth suicide ideation and suicide

attempts during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 as

Address correspondence to Ryan M. Hill, PhD, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine,

6701 Fannin St, Suite B.19810, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail: ryan.hill@bcm.edu

compared with 2019. Increases in suicide ideation and

suicide attempts appear to correspond to times of

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). increased COVID-19–related concerns.

Copyright © 2021 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to To cite: Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, et al. Suicide Ideation

this article to disclose. and Attempts in a Pediatric Emergency Department

Before and During COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):

FUNDING: No external funding. e2020029280

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

PEDIATRICS Volume 147, number 3, March 2021:e2020029280 ARTICLE

Suicide is the second leading cause of discharge. This research was

death among children and approved by the appropriate

adolescents aged 10 to 17 years in institutional review board.

the United States, and suicide rates

In the current study, we examine data

have increased in the age group over

from January to July 2019 and

the past 20 years.1 These statistics

January to July 2020. A total of 18 247

coincide with recent literature that

youth aged 11 to 21 years were seen

revealed a 92% increase in annual

FIGURE 1 in the ED, of whom 12 827 completed

emergency department (ED) visits for

Patients screened in the pediatric ED, January the suicide-risk screen (Fig 1).

suicide ideation and attempts for

to July 2019 and January to July 2020. Participants had a mean age of

children without a statistically

14.52 years (SD = 2.22; with 88.8%

significant increase in overall ED

aged 11–17 years). Respondents self-

visits.2 Additionally, youth suicide- The goal of the current study was to

identified as follows: 59.0% female (n

related behaviors result in 4 to 5 ED examine rates of suicide ideation and

= 7570) and 41.0% male (n = 5257),

visits per year for every 1000 youth attempts reported during routine

47.5% Hispanic and/or Latinx (n =

aged 15 to 19 years,3 costing an suicide-risk screening in a pediatric

6091), 26.8% non-Hispanic white (n

estimated $15.5 billion annually.4 ED. We report changes in rates of

= 3433), 19.1% non-Hispanic Black or

positive suicide-risk screen results

In multiple reports, elevated rates of African American (n = 2455), 2.6%

and compare rates of positive screen

mental health concerns have been non-Hispanic Asian (n = 338), 0.1%

results from January to July 2020

identified during the coronavirus American Indian or Alaskan native (n

with those from the same period in

disease 2019 (COVID-19) = 16), 0.1% native Hawaiian or Pacific

2019. Potential demographic

pandemic.5–7 In a recent study of US Islander (n = 12), and 1.2%

differences are evaluated to

adults, .40% of respondents multiracial (n = 153). Demographic

determine if specific demographic

reported adverse mental health or data were unavailable for 2.6% of the

groups were disproportionately

increased substance use in June respondents (n = 329). Overall, 3.5%

impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic

2020.8 Furthermore, research reveals (n = 454) of participants reported

with respect to suicide-related

that participants in shelter-in-place or a chief complaint of suicidal thoughts

behaviors.

lockdown because of COVID-19 or behaviors at the time of their visit.

experienced increasing rates of

suicide ideation as months passed, METHODS Measures

whereas participants not under these The 7-item screening version of the

COVID-19 restrictions did not.9 Participants and Procedures C-SSRS was used to screen for suicide

Consequently, experts in the field Data were drawn from the electronic risk.20 The C-SSRS uses the Columbia

have published resources to inform health record of a large pediatric ED Classification Algorithm of Suicide

treating suicide using the in a major metropolitan area in Texas. Assessment for categorizing suicide-

Collaborative Assessment and Youth aged 11 and older who related phenomena.21 The C-SSRS has

Management of Suicidality,10 and presented to the ED within any of excellent documented reliability and

safety planning11 during the COVID- three connected pediatric hospitals predictive validity in both youth and

19 pandemic. Among adolescents, for any presenting complaint were adults.19–22 Youth were asked to

greater levels of negative COVID-19 asked to complete the screening complete 2 items assessing passive

experiences were associated with version of the Columbia-Suicide and active suicide ideation in the

increased depressive symptoms and Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)19 via previous month. If active suicide

anxiety.12 However, although many an electronic tablet. Exclusion criteria ideation was present, 3 additional

have speculated about the impacts of included the following: patient or items were presented, further

the COVID-19 pandemic on youth and legal guardian refusal, unresponsive assessing the severity of suicide

adults,13,14 empirical data revealing on arrival due to medical condition, ideation (method, intent, and plan).

elevated rates of mental health or intellectual disability that All youth also responded to a single

concerns during this period have precluded the ability to read and item assessing lifetime suicide

been provided in few studies.15,16 In respond to the questions. All positive attempt history. If a positive suicide

fact, authors of recent studies have suicide-risk screen results were attempt history was noted, youth

reported that the rates of death by addressed via standard hospital were also asked to identify whether

suicide in children and adults have protocols, including an assessment of any suicide attempt had occurred

not changed since the onset of the suicide risk and appropriate safety within the previous 3 months. All

pandemic.17,18 steps to ameliorate suicide risk before items are asked by using “yes” and

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

2 HILL et al

“no” response options. Screens were 1.45 times higher in July 2020 Hispanic and/or Latinx, with non-

provided in both English and Spanish. compared with July 2019. Hispanic white as the reference

group. The first step of the model

For recent suicide attempts, x2

Data Analyses contained year and race and ethnicity

difference tests identified significant

Data were evaluated by using SPSS as predictors of the likelihood of

differences in the rate of suicide

version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM recent suicide ideation. The overall

attempts in February, March, April,

Corporation). Data were first cleaned model was statistically significant (x23

and July 2020 compared with those

to remove cases that did not meet = 23.48; P , .001; Nagelkerke R2 =

same months in 2019. The odds of

inclusion criteria or those with 0.005). Both variables were

a recent suicide attempt were 1.58,

missing data on the C-SSRS screen. A statistically significant predictors,

2.34, 1.75, and 1.77 times higher in

search for duplicate patients in any indicating that recent suicide ideation

February, March, April, and July 2020

given month was conducted, and was more frequent in 2020 and less

compared with those same months in

none were identified. Suicide-risk frequent among Hispanic and/or

2019, respectively. Figure 2 reveals

screens were then scored according Latinx youth (as compared with non-

rates of positive screen results by

to two algorithms: Recent suicide Hispanic white youth). In the second

month and year.

ideation was defined as a positive step, the interaction term was added

(“yes”) response to any of the items Demographic Characteristics to the model. This second step was

assessing past-month suicide Associated With Positive Screen not a statistical improvement in the

ideation. Recent suicide attempt was Results model (x22 = 1.40; P = .50), and the

defined as a positive (“yes”) response interaction between year and race

To evaluate whether specific

to item 7, which assessed suicide and ethnicity was not statistically

demographic subgroups were

attempts in the previous 3 months. significant, indicating that no racial or

disproportionately impacted, two

Descriptive statistics were calculated, ethnic group reported a greater

logistic regression models were

followed by a series of x2 difference increase in the likelihood of recent

examined to evaluate the effects of

tests to examine the difference in suicide ideation from 2019 to 2020. A

sex and race and/or ethnicity on the

rates of suicide ideation and attempts similar pattern of results was found

likelihood of a positive suicide-risk

in the months pre- and post-COVID- for both sex and race and ethnicity

screen result. Results are presented

19. Finally, binary logistic regressions when recent suicide attempt was the

in Table 2. Data for March to July

were used to examine demographic outcome variable (Table 2).

were evaluated in a single model,

differences associated with positive with any recent suicide ideation as

screen results. Because of the the outcome. For sex, the first step of DISCUSSION

exploratory nature of the study, the model contained year and sex as

power analyses were not conducted. In this study, we evaluated whether

predictors of the likelihood of recent

rates of youth suicide-related

suicide ideation. The overall model

behaviors have been elevated during

was statistically significant (x22 =

RESULTS the COVID-19 pandemic by examining

155.22; P , .001; Nagelkerke R2 =

rates of positive results on suicide-

Prevalence of Suicide-Related 0.029). Both variables were

risk screens administered as routine

Behaviors, 2019–2020 statistically significant predictors,

screening in a pediatric ED.

indicating that recent suicide ideation

Across the entire study period, 15.8% Comparison of the rate of suicide

was more frequent in 2020 and

(n = 2033) reported past-month screen results positive for recent

among female participants. In the

suicide ideation, and 4.3% (n = 554) suicide ideation revealed significantly

second step, the interaction term was

reported a recent suicide attempt increased rates of ideation in March

added to the model. This second step

(past 3 months). Rates of screen and July 2020 as compared with

was not a statistical improvement in

results positive for recent suicide screening rates in March and July

the model (x21 = 0.76; P = .38), and the

ideation and suicide attempts by 2019. Similarly, screen results

interaction between year and sex was

month and year are reported in positive for recent suicide attempts

not statistically significant, indicating

Table 1. The x2 difference tests were higher in February, March, April,

that neither sex reported a greater

identified significant differences in and July 2020 than in those same

increase in the likelihood of recent

the rate of recent suicide ideation in months in 2019. Of note, the number

suicide ideation from 2019 to 2020.

March and July 2020 compared with of ED visits was substantially reduced

those same months in 2019. The odds In the second model, race and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

of recent suicide ideation were ethnicity was evaluated, categorized Consequently, direct comparison of

1.60 times higher in March 2020 as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic rates across years should be made

compared with March 2019 and Black or African American, and with caution.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

PEDIATRICS Volume 147, number 3, March 2021 3

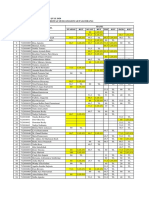

TABLE 1 Percentage of Screen Results Positive for Any Suicide-Related Behaviors and Recent Suicide Attempts

Month 2019, % (n) 2020, % (n) x2 (df) P Odds

Ratio

Recent suicide ideation

January 16.0 (92) 14.6 (143) 0.569 (1) .45 0.90

February 15.7 (188) 15.4 (152) 0.031 (1) .86 0.98

March 14.3 (189) 21.1 (167) 16.069 (1) ,.001 1.60

April 16.3 (213) 16.5 (82) 0.012 (1) .91 1.02

May 16.1 (200) 17.3 (106) 0.412 (1) .52 1.09

June 14.8 (146) 18.2 (131) 3.579 (1) .06 1.28

July 11.9 (106) 16.3 (118) 6.734 (1) .009 1.45

Recent suicide attempts

January 4.0 (22) 3.7 (36) 0.024 (1) .72 0.91

February 3.3 (40) 5.2 (51) 4.540 (1) 0.3 1.58

March 3.3 (43) 7.3 (58) 17.910 (1) ,.001 2.34

April 3.3 (43) 5.6 (28) 5.227 (1) .02 1.75

May 4.0 (50) 4.7 (29) 0.506 (1) .48 1.18

June 3.7 (37) 5.3 (38) 2.331 (1) .13 1.43

July 3.7 (33) 6.4 (46) 6.144 (1) .01 1.77

df, degree of freedom.

Rates of positive suicide-risk screen appears to have been an early as early outbreaks in some parts of

results were not uniformly higher increase in suicide-related behaviors the United States. However, in May

after the outbreak of the COVID-19 between February and April 2020. 2020, the state of Texas began to lift

pandemic in the United States in This time frame corresponds to the COVID-19 restrictions, which may

March 2020, as indicated by the lack onset of the pandemic in the United have also reduced fears and concerns

of statistically significant differences States, including initial stay-at-home regarding COVID-19, allowed youth to

in rates of positive screen results, orders and social distancing efforts resume interrupted schedules, and

particularly in May and June. There that went into effect in March as well increased social contacts and reduced

social isolation. In June, Texas saw

a resurgence of COVID-19 cases,23

which triggered the reintroduction of

COVID-19 restrictions across

a number of public sectors in early

July as well as renewed efforts to

increase social distancing. The data

indicate that at this same time, rates

of screen results positive for suicide-

related behaviors also increased.

Thus, a possible explanation of the

data is that the variability in the

statistical results appears to follow

the historical context of COVID-19

cases, particularly regarding the

general level of community fear or

isolation due to school cancellations

and social distancing efforts in the

region where data collection

occurred.

The results of this study should be

considered in the context of the study

limitations. Critically, we are unable

to make concrete causal influences

because historical factors other than

FIGURE 2 the COVID-19 pandemic occurred

A and B, Rates of screen results positive for suicide ideation (A) and attempt (B), January to July. between 2019 and 2020.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

4 HILL et al

TABLE 2 Demographic Characteristics Associated With Positive Screen Results

Predictor Recent Suicide Ideation Recent Suicide Attempt

B SE P x2 B SE P x2

Model 1

Block 1 x22 = 155.22, P , .001, R2 = 0.029 x22 = 77.79, P , .001, R2 = 0.028

Year 20.22 0.06 ,.001 — 20.51 0.10 ,.001 —

Sex (female) 0.72 0.06 ,.001 — 0.80 0.12 ,.001 —

Block 2 x21 = 0.76, P = .38, R2 = 0.029 x21 = 0.73, P = .39, R2 = 0.028

Year 20.14 0.11 .21 — 20.36 0.21 .08 —

Sex (female) 0.79 0.10 ,.001 — 0.91 0.18 ,.001 —

Sex (female) 3 year 20.11 0.14 .38 — 20.20 0.24 .39 —

Model 2

Block 1 x23 = 23.48, P , .001, R2 = 0.005 x23 = 43.46, P , .001, R2 = 0.017

Year 20.24 0.06 ,.001 — 20.57 0.11 ,.001 —

African American or Black 20.01 0.08 .93 — 0.09 0.14 .55 —

Hispanic 20.17 0.07 .01 — 20.38 0.13 .002 —

Block 2 x22 = 1.40, P = .50, R2 = 0.005 x22 = 1.54, P = .46, R2 = 0.018

Year 20.18 0.11 .10 — 20.74 0.19 ,.001 —

African American or Black 0.11 0.13 .42 — 0.02 0.20 .94 —

Hispanic 20.15 0.11 .17 — 20.54 0.18 .002 —

African American or Black 3 year 20.19 0.17 .26 — 0.14 0.29 .62 —

Hispanic 3 year 20.04 0.14 .80 — 0.31 0.25 .22 —

For race and/or ethnicity, the comparator is non-Hispanic white youth; for sex, the comparator is male sex. B, regression coefficient; —, not applicable.

Consequently, although the pattern of or screening programs. In particular, a pediatric ED during the

the data indicates a possible because results appeared to follow 2020 COVID-19 pandemic were

association between rates of positive localized patterns of COVID-19 statistically elevated compared

suicide-risk screen results and response, additional research is with the same period in the previous

COVID-19–related social and cultural needed to determine if these results year. These data indicate that the

changes, we were not able to evaluate replicate in other regions, where effects of the pandemic, broadly

the potential impacts of other localized COVID-19 response patterns defined, may be associated with

historical sociopolitical events. differed. increased rates of suicide ideation

Additionally, hospital pediatric ED Additional research is also needed to among youth aged 11 to 21. Future

patient volumes were reduced during evaluate unique risk and protective researchers should evaluate how

the COVID-19 pandemic, which may factors that may be associated with various social, emotion, behavioral,

have introduced bias into the sample, suicide risk in the context of a global and cultural factors may be

which we were unable to discern. pandemic.25 In the current study, we associated with increased rates of

Furthermore, data indicate that 40% were not able to evaluate individual suicide-related behavior during

of adolescents who are suicidal visit effects of pandemic-related fears or a global pandemic.

an ED in the year before their stresses, social distancing and other

deaths,24 indicating that patients in preventive measures (eg, cancelling ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

the ED constitute a high-risk in-person classes, distance learning,

population. Thus, the rates of suicide We acknowledge the efforts of Tarra

isolation from peers), and stay-at- Kerr and the nursing staff who

ideation and suicide attempts home or mask orders on suicide-

reported here may not be reflective of implemented the universal

related behaviors. In future efforts, suicide-risk screen. Without their

the true rates within the population. researchers should aim to evaluate

In addition, given the reduced rate of efforts, this work would not have

which aspects of the pandemic and been possible.

ED visits during the pandemic, it is pandemic responses have the greatest

possible that only patients with the impact on youth suicide-related

most severe cases came to the ED, behaviors to identify potential

resulting in elevated rates of suicide ABBREVIATIONS

avenues for countering the increased

ideation and attempt due to the suicide risk.26 COVID-19: coronavirus disease

increased overall severity of cases. 2019

Data are also drawn from a single C-SSRS: Columbia-Suicide Severity

hospital system and a single CONCLUSIONS

Rating Scale

screening methodology, and so results Rates of positive suicide-risk screen ED: emergency department

may not generalize to other regions results for youth seeking care in

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

PEDIATRICS Volume 147, number 3, March 2021 5

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and suicidal risk: the telepsychotherapy use 19. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al.

Prevention. WISQARSTM - web-based of CAMS. J Psychother Integr. 2020; The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating

injury statistics query and reporting 30(2):226–237 Scale: initial validity and internal

system. 2020. Available at: www.cdc. consistency findings from three

11. Pruitt LD, Mcintosh LS, Reger G. Suicide

gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. multisite studies with adolescents and

safety planning during a pandemic: the

Accessed August 20, 2020 adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):

implications of COVID-19 on coping with

2. Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B. 1266–1277

a crisis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;

Suicidal attempts and ideation among 50(3):741–749 20. Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley

children and adolescents in US B, Davies M. Columbia Classification

emergency departments, 2007–2015. 12. Standish K. A coming wave: suicide and Algorithm of Suicide Assessment

JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):598–600 gender after COVID-19 [published online (C-CASA): classification of suicidal

ahead of print July 20, 2020]. J Gend events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal

3. Ting SA, Sullivan AF, Boudreaux ED, Stud. doi:10.1080/

Miller I, Camargo CA Jr. Trends in US risk analysis of antidepressants.

09589236.2020.1796608 Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):

emergency department visits for

attempted suicide and self-inflicted 13. Silliman Cohen RI, Adlin Bosk E. 1035–1043

injury, 1993–2008. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Vulnerable youth and the COVID-19 21. Gipson PY, Agarwala P, Opperman KJ,

2012;34(5):557–565 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1): Horwitz A, King CA. Columbia-suicide

e20201306 severity rating scale: predictive validity

4. Shepard DS, Gurewich D, Lwin AK, Reed

GA Jr., Silverman MM. Suicide and 14. Alvis L, Douglas R, Shook N, Oosterhoff with adolescent psychiatric emergency

suicidal attempts in the United States: B. Associations between adolescents’ patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;

costs and policy implications. Suicide prosocial experiences and mental 31(2):88–94

Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(3):352–362 health during the COVID-19 pandemic 22. Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, King CA. Predicting

5. Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, et al. Mental health [preprint posted online May 7, 2020]. future suicide attempts among

problems and social media exposure PsyArXiv. doi:10.31234/osf.io/2s73n adolescent and emerging adult

during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 15. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental psychiatric emergency patients. J Clin

2020;15(4):e0231924 health: a review of the existing Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(5):

literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52: 751–761

6. Zhu S, Wu Y, Zhu CY, et al. The immediate

mental health impacts of the COVID-19 102066 23. Almukhtar S, Aufrichtig A, Barnard A,

pandemic among people with or 16. Jolly TS, Batchelder E, Baweja R. Mental et al. Texas coronavirus map and case

without quarantine managements. health crisis secondary to COVID-19- count. The New York Times. April 1,

Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:56–58 related stress: a case series from 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.

7. Mamun MA, Sakib N, Gozal D, et al. The a child and adolescent inpatient unit. com/interactive/2020/us/texas-

COVID-19 pandemic and serious Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. coronavirus-cases.html. Accessed

psychological consequences in 2020;22(5):20l02763 August 24, 2020

Bangladesh: a population-based 24. Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C,

17. Isumi A, Doi S, Yamaoka Y, Takahashi K,

nationwide study. J Affect Disord. 2021; et al. Health care contacts in the year

Fujiwara T. Do suicide rates in children

279:464–472 before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med.

and adolescents change during school

8. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. closure in Japan? The acute effect of 2014;29(6):870–877

Mental health, substance use, and the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on 25. Monteith LL, Holliday R, Brown TL,

suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 child and adolescent mental health. Brenner LA, Mohatt NV. Preventing

pandemic – United States, June 24–30, Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(pt 2):104680 suicide in rural communities during the

2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. COVID-19 pandemic [published online

2020;69(32):1049–1057 18. Leske S, Kolves K, Crompton D,

ahead of print April 13, 2020]. J Rural

Arensman E, de Leo D. Real-time suicide

9. Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Health. doi:10.1111/jrh.12448

mortality data from police reports in

Allbright MC, Dailey NS. Trends in Queensland, Australia, during the 26. Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, et al.

suicidal ideation over the first three COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted Factors associated with mental health

months of COVID-19 lockdowns. time-series analysis. [published disorders among university students in

Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113390 correction appears in Lancet France confined during the COVID-19

10. Jobes DA, Crumlish JA, Evans AD. The Psychiatry. 2021;8(1):e1]. Lancet pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):

COVID-19 pandemic and treating Psychiatry. 2021;8(1):58–63 e2025591

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

6 HILL et al

Suicide Ideation and Attempts in a Pediatric Emergency Department Before and

During COVID-19

Ryan M. Hill, Katrina Rufino, Sherin Kurian, Johanna Saxena, Kirti Saxena and

Laurel Williams

Pediatrics 2021;147;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280 originally published online December 16, 2020;

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/147/3/e2020029280

References This article cites 21 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/147/3/e2020029280#BI

BL

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Emergency Medicine

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/emergency_medicine_

sub

Psychiatry/Psychology

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psycholog

y_sub

Public Health

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/public_health_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

Suicide Ideation and Attempts in a Pediatric Emergency Department Before and

During COVID-19

Ryan M. Hill, Katrina Rufino, Sherin Kurian, Johanna Saxena, Kirti Saxena and

Laurel Williams

Pediatrics 2021;147;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280 originally published online December 16, 2020;

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/147/3/e2020029280

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2021

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on March 22, 2021

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Vijay Law Series List of Publications - 2014: SN Subject/Title Publisher Year IsbnDocument3 pagesVijay Law Series List of Publications - 2014: SN Subject/Title Publisher Year IsbnSabya Sachee Rai0% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Seventh Day Adventist Quiz by KnowingTheTimeDocument4 pagesSeventh Day Adventist Quiz by KnowingTheTimeMiiiTheart100% (3)

- BS Assignment Brief - Strategic Planning AssignmentDocument8 pagesBS Assignment Brief - Strategic Planning AssignmentParker Writing ServicesNo ratings yet

- A Study On Mistakes and Errors in Consecutive Interpretation From Vietnamese To English. Dang Huu Chinh. Qhf.1Document38 pagesA Study On Mistakes and Errors in Consecutive Interpretation From Vietnamese To English. Dang Huu Chinh. Qhf.1Kavic100% (2)

- Why Socioeconomic Status Affects The Health of ChildrenDocument4 pagesWhy Socioeconomic Status Affects The Health of ChildrenmikoNo ratings yet

- Delayed Antibiotic Prescription For Children With Respiratory Infections: A Randomized TrialDocument13 pagesDelayed Antibiotic Prescription For Children With Respiratory Infections: A Randomized TrialmikoNo ratings yet

- Hasil CBT Minor Periode Juli 2020Document3 pagesHasil CBT Minor Periode Juli 2020mikoNo ratings yet

- The Growth and Development Status of Homeless Children Entering Shelters in BostonDocument4 pagesThe Growth and Development Status of Homeless Children Entering Shelters in BostonmikoNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Severe Sars-Cov-2 Infection: BackgroundDocument14 pagesFactors Associated With Severe Sars-Cov-2 Infection: BackgroundmikoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument11 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- Drug Induced Anaphylaxis During General Anesthesia in 14 Tertiary Hospitals in Japan: A Retrospective, Multicenter, Observational StudyDocument7 pagesDrug Induced Anaphylaxis During General Anesthesia in 14 Tertiary Hospitals in Japan: A Retrospective, Multicenter, Observational StudymikoNo ratings yet

- Toatj 14 80 PDFDocument10 pagesToatj 14 80 PDFmikoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument7 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument11 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- Anesthetics and AnesthesiologyDocument8 pagesAnesthetics and AnesthesiologymikoNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Approach For Patient With Hereditary AngioedemaDocument3 pagesAnaesthetic Approach For Patient With Hereditary AngioedemamikoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 112Document4 pagesInternational Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 112mikoNo ratings yet

- PRM2017 1721460 PDFDocument6 pagesPRM2017 1721460 PDFmikoNo ratings yet

- Notes Structs Union EnumDocument7 pagesNotes Structs Union EnumMichael WellsNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection and Public Education EssayDocument6 pagesEqual Protection and Public Education EssayAccount YanguNo ratings yet

- A Research Presented To Alexander T. Adalia Asian College-Dumaguete CampusDocument58 pagesA Research Presented To Alexander T. Adalia Asian College-Dumaguete CampusAnn Michelle PateñoNo ratings yet

- Aleister Crowley Astrological Chart - A Service For Members of Our GroupDocument22 pagesAleister Crowley Astrological Chart - A Service For Members of Our GroupMysticalgod Uidet100% (3)

- Public Service: P2245m-PorkDocument3 pagesPublic Service: P2245m-PorkDaniela Ellang ManuelNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme Big Cat FactsDocument3 pagesMark Scheme Big Cat FactsHuyền MyNo ratings yet

- Fsi GreekBasicCourse Volume1 StudentTextDocument344 pagesFsi GreekBasicCourse Volume1 StudentTextbudapest1No ratings yet

- Individual Assignment: Prepared By: Tigist WoldesenbetDocument12 pagesIndividual Assignment: Prepared By: Tigist WoldesenbetRobel YacobNo ratings yet

- Boxnhl MBS (Design-D) Check SheetDocument13 pagesBoxnhl MBS (Design-D) Check SheetKumari SanayaNo ratings yet

- Blue Mountain Coffee Case (ADBUDG)Document16 pagesBlue Mountain Coffee Case (ADBUDG)Nuria Sánchez Celemín100% (1)

- Rules and IBA Suggestions On Disciplinary ProceedingsDocument16 pagesRules and IBA Suggestions On Disciplinary Proceedingshimadri_bhattacharje100% (1)

- Magtajas vs. PryceDocument3 pagesMagtajas vs. PryceRoyce PedemonteNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1Alyssa DuranoNo ratings yet

- Voucher-Zona Wifi-@@2000 - 3jam-Up-764-04.24.24Document10 pagesVoucher-Zona Wifi-@@2000 - 3jam-Up-764-04.24.24AminudinNo ratings yet

- Adjective Clauses: Relative Pronouns & Relative ClausesDocument4 pagesAdjective Clauses: Relative Pronouns & Relative ClausesJaypee MelendezNo ratings yet

- Ramin Shamshiri Risk Analysis Exam2 PDFDocument8 pagesRamin Shamshiri Risk Analysis Exam2 PDFRedmond R. ShamshiriNo ratings yet

- Razom For UkraineDocument16 pagesRazom For UkraineАняNo ratings yet

- Writing Ielts Tasks Andreea ReviewDocument18 pagesWriting Ielts Tasks Andreea ReviewRody BudeșNo ratings yet

- Travel Smart: Assignment 1: Project ProposalDocument14 pagesTravel Smart: Assignment 1: Project ProposalcattytomeNo ratings yet

- Contents:: Project ProgressDocument22 pagesContents:: Project ProgressJosé VicenteNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document16 pagesChapter 1MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Your ManDocument5 pagesYour ManPaulino JoaquimNo ratings yet

- Explicit and Implicit Grammar Teaching: Prepared By: Josephine Gesim & Jennifer MarcosDocument17 pagesExplicit and Implicit Grammar Teaching: Prepared By: Josephine Gesim & Jennifer MarcosJosephine GesimNo ratings yet

- Design & Evaluation in The Real World: Communicators & Advisory SystemsDocument13 pagesDesign & Evaluation in The Real World: Communicators & Advisory Systemsdivya kalyaniNo ratings yet

- MidtermDocument8 pagesMidtermBrian FrenchNo ratings yet

- Isolasi Dan Karakterisasi Runutan Senyawa Metabolit Sekunder Fraksi Etil Asetat Dari Umbi Binahong Cord F L A Steen S)Document12 pagesIsolasi Dan Karakterisasi Runutan Senyawa Metabolit Sekunder Fraksi Etil Asetat Dari Umbi Binahong Cord F L A Steen S)Fajar ManikNo ratings yet