Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PerformanceappraisalTaeheeKim ROPPA2014

Uploaded by

NeelampariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PerformanceappraisalTaeheeKim ROPPA2014

Uploaded by

NeelampariCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/276270443

Public Employees and Performance Appraisal A Study of

Antecedents to Employees’ Perception of the Process

Article in Review of Public Personnel Administration · October 2014

DOI: 10.1177/0734371X14549673

CITATIONS READS

47 4,048

2 authors:

Taehee Kim Marc Holzer

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

2 PUBLICATIONS 59 CITATIONS 264 PUBLICATIONS 2,705 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Global E-Governance Survey 2018 View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Marc Holzer on 20 October 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

549673

research-article2014

ROPXXX10.1177/0734371X14549673Review of Public Personnel AdministrationKim and Holzer

Article

Review of Public Personnel Administration

1–26

Public Employees and © The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

Performance Appraisal: A sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0734371X14549673

Study of Antecedents to rop.sagepub.com

Employees’ Perception of the

Process

Taehee Kim1 and Marc Holzer2

Abstract

There is considerable agreement that organizations can benefit from using performance

appraisal. Nevertheless, some studies find that both supervisors and employees

have negative reactions to the process. This article addresses this contradiction by

emphasizing the importance of cognitive aspects of performance appraisal. Without

understanding individual employees’ reactions to performance appraisal and its

supportive organizational context, it is less likely for performance appraisal to

be used for its original objective, which is performance improvement. Given the

importance of employee acceptance of a performance measurement system, this

article attempts to identify key factors which can heighten employee acceptance of

performance appraisal using data from the 2005 Merit Principles Survey. The findings

indicate that the developmental use of performance appraisal, employee participation

in performance standard setting, the quality of the relationship they have with their

supervisors, and employee perceived empowerment are positively associated with

employee acceptance of performance appraisal.

Keywords

employee attitudes, behavior, motivation, Federal government HRM, workplace

environment/culture, job analysis/evaluation, organizational behavior/development

1University of Hawaii, Honolulu, USA

2Rutgers University–Newark, NJ, USA

Corresponding Author:

Taehee Kim, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2424 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Email: tkim3@hawaii.edu

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

2 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Introduction

Performance appraisal is an important management tool for measuring employee job

performance, clarifying personnel decisions such as promotion, demotion, or reten-

tion, as well as helping develop employee capacity through providing feedback or

training. It also contributes to advancing supervisor–employee understanding and

reinforces organizational values (Daley, 1992; Murphy & Cleveland, 1991). Moreover,

effective performance appraisal is believed to motivate employees to strive for perfor-

mance improvement by linking appraisals to performance-contingent rewards (Perry,

Petrakis, & Miller, 1989). In spite of considerable agreement that organizations can

benefit from using performance appraisal, when it comes to its practice, its theorized

benefits appear to remain under-fulfilled in some cases. Some studies found that nei-

ther supervisors nor employees support using it (Berman, Bowman, West, & Van Wart,

2006; Deming, 1986; Kim & Rubianty, 2011; Nigro, 1981). Especially in the public

sector, anecdotal observations and survey findings indicate that the extrinsic compo-

nent embedded in performance appraisal may cause a crowding out effect on employee

motivation, resulting in perceived stress, demotivation, or even burnout (Kellough &

Nigro, 2002; Pearce & Perry, 1983). In addition, further evidence shows decreasing

confidence in the efficacy, integrity, and fairness of public performance appraisal

(Gaertner & Gaertner, 1985; Kellough & Nigro, 2002; Pearce & Perry, 1983). For

example, Kunreuther (2009) explains the prevalent negative attitudes toward perfor-

mance appraisal among federal employees. In his survey, some employees expressed

concerns that their performance has not been fairly rated, whereas some supervisory-

level employees perceive providing performance feedback as conflicting with other

duties, and is therefore a distasteful chore. Moreover, the majority of the employees in

this survey also believe that there is a quota system for performance ratings.

Despite such problems and challenges, and given the lack of alternatives, the effec-

tive use of performance appraisals and their implementation remains a challenging

task for public managers (Berman et al., 2006; Deming, 1986; Kim & Rubianty, 2011;

Nigro, 1981; Wright, 2004). How can we make it work, given its practical flaws and

difficulties?

In an effort to perfect the appraisal process and maximize its benefits, a large litera-

ture has emerged on performance appraisal, most of which has centered on designing

better performance appraisal techniques or instruments, that is, focusing on its psycho-

metric issues such as the lack of a fair and objective appraisal instrument, the issue of

measurement (e.g., rating error, rating leniency), and appraisal frequency (Korsgaard

& Roberson, 1995; Landy & Farr, 1980; Murphy & Cleveland, 1991, 1995). This has

resulted in many studies and some progress. As Kikoski (1998) noted, however, it

seems that, “The delivery of the performance appraisal still tends to be resisted” (p.

302). One limitation of that research is that they did not consider the importance of the

cognitive aspects of performance appraisal, while overemphasizing the system design

(Cawley, Keeping, & Levy, 1998; Murphy & Cleveland, 1995). As Daley (1992)

points out, no matter how well a performance system is designed, it will become use-

less if there is a lack of employee acceptance of the performance appraisal system, or

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 3

if they do not see it as useful or valid. Levy and Williams (2004) also note, “Good

psychometrics cannot make up for negative perceptions on the part of those involved

in the system” (p. 890). Without understanding individual employee reactions to per-

formance appraisal, and its supportive organizational context, it is less likely for per-

formance appraisal to be used for its original objective, which is performance

improvement. In addition, the negative perceptions of employees toward performance

management cause resistance to it, leading to job-related stress, burnout, and even

underperformance (Gabris & Ihrke, 2000).

In this regard, a growing number of studies have started to examine employee reactions

to performance appraisal as one effort to address its cognitive aspects (Gabris & Ihrke,

2000; Roberts, 2003), but studies that empirically examine this issue, and consider its con-

text, are less frequent and therefore need more exploration (Levy & Williams, 2004).

In light of this gap in the literature, the purpose of this research is to build a case for

recognizing the importance of employee behavior, especially their acceptance of per-

formance appraisal. More specifically, this article aims to empirically examine under

which contextual circumstances employee acceptance of performance measurement

may be heightened using data from the Merit Principles Survey 2005. Building on

organizational justice theories (Gabris & Ihrke’s, 2000; Greenberg, 1986a, 1986b),

this study measured the extent to which employees accept the performance appraisal

process using two constructs—procedural justice and distributional justice. Procedural

justice (process) is operationalized as the extent to which employees believe that their

job performance is fairly assessed and their supervisor has the capacity to assess their

performance in a fair and valid manner. Distributional justice (outcomes) is operation-

alized as the extent to which employees believe that the rewards they received from

the organization is related to their performance inputs and the extent to which employ-

ees believe that their work outcomes, such as rewards and recognition, are fair (Fields,

2002; Niehoff & Moorman, 1993). Among two major functions of performance

appraisal—evaluation and development (Meyer, Kay, & French, 1965; Moussavi &

Ashbaugh, 1995)—this article suggests that the developmental use of performance

appraisal contributes to heightening employee acceptance of the process. This article

also suggests that the trusting relationships between supervisors as raters and employ-

ees as ratees, and employee perceived empowerment, matter for fostering employee

acceptance. This study contributes to the current literature on performance appraisal

by advancing our understanding of the process, refining related theories on perfor-

mance appraisal, and capitalizing on public employee perceptions and perspectives.

The following section reviews the previous literature on this issue, followed by

research hypotheses drawn from the literature. This article then concludes with impli-

cations and possible future research directions.

Theories and Hypotheses

Performance appraisal refers to evaluation by public managers of their subordinates’

job performance with the aim of managing and improving individual performance

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

4 Review of Public Personnel Administration

(Daley, 1992; Fletcher, 2001; Levy & Williams, 2004; Murphy & Cleveland, 1991).

Performance appraisal can provide either positive outcomes or negative outcomes to

organizational members who are involved in the process, and those outcomes influ-

ence members’ willingness to become further involved with the system (Carroll &

Schneier, 1982). The outcomes can be perceived as either positive or negative depend-

ing on the extent to which performance appraisal serves participating members’ pur-

poses and needs. Previous studies have called more attention to appraisal format,

focusing on psychometric and accuracy issues related to performance appraisal, while

less attention has been paid to the attitudes of job incumbents toward performance

appraisal and its supporting organizational contexts. However, designing and improv-

ing the process alone is not sufficient for it to be effective considering the lack of

understanding on the part of researchers with regard to employee attitudes toward

performance appraisal and the context where such appraisal takes place (Murphy &

Cleveland, 1995).

A handful of studies have begun to emphasize that organizational members’ accep-

tance of performance measurement efforts (both supervisors or subordinates) is criti-

cal to the overall success of performance management and its effectiveness, because

their attitudes affect their behaviors (Kim & Rubianty, 2011; Roberts, 1994; Roberts &

Pavlak, 1996). This is because, as Lawler (1967) noted, “Attitudes toward the equity

and acceptability of a rating system then are functions not only of the system itself but

also of organizational and individual characteristics” (p. 379). In particular, he sug-

gested that among individual and organizational characteristics, individual employees’

feedback-seeking behavior and participatory management style contributes to height-

ening members’ acceptability of performance appraisal. He asserts that when employ-

ees’ need for feedback is strong, and managers are willing to involve employees in the

decision-making process, the acceptability of performance appraisal among job

incumbents will be greater (Dickinson, 1993; Lawler, 1967). In other words, even

though we may be able to design a technically sound and accurate performance

appraisal system, without employee acceptance of performance appraisal, its quality

and its overall success can be compromised (Cardy & Dobbins, 1994; Hedge &

Borman, 1995; Keeping & Levy, 2000; Murphy & Cleveland, 1995). Others also sug-

gest that the reasons for managers’ or employees’ resistance to a performance appraisal

should be identified and reduced to maximize the effectiveness of performance

appraisal (Carroll & Schneier, 1982; Lovrich, 1987). Murphy and Cleveland (1995)

also make a strong statement that, “An employee’s reaction to performance measure-

ment is one of the neglected criteria that might be critical in evaluating the success of

an appraisal system” (p. 310). Roberts (1994) explained possible consequences of

unaccepted performance measurement efforts:

If employees are hostile and reject the system, the raters may be unwilling or unable to

effectively implement performance appraisal due to the costs attached to employee

resistance. Raters that lack motivation to effectively implement the process will meet

only the minimum requirements, and with performance appraisal, the minimum is rarely

sufficient. (p. 526)

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 5

He pointed out that this lack of motivation may bring rating errors, ambiguity in

performance feedback, and lack of use of performance appraisal information. Roberts

and Pavlak’s (1996) study provides supporting evidence that, in a survey of personnel

managers in 314 municipalities, about 89 respondents recognized the importance of

employee acceptance of performance appraisal for its success. The findings of their

study suggest agreement on interpreting performance information pertaining to super-

visors and employees, support of employee growth, the employee–supervisor relation-

ship, and the supervisor’s commitment, are preconditions for acceptance. Cardy and

Dobbins (1994) also suggested that when employees perceive a performance appraisal

process as unfair, unsatisfying, and/or inequitable, it may fail to achieve its outcomes.

Thus, it seems that there is a general consensus among performance appraisal research-

ers and practitioners that employee acceptance of a performance appraisal system is

important (Cardy & Dobbins, 1994; Lawler, 1967; Murphy & Cleveland, 1991; Hedge

& Teachout, 2000).

When applied to the performance appraisal context, employee acceptance of the

process means that they agree to undertake appraisal because they perceive or believe

the process to be fair, valid, and beneficial. Carroll and Schneier (1982) suggested that

what accounts for the level of acceptance of the appraisal process by organizational

members is employee belief that their performance is assessed in a fair, valid, and

accurate manner.

Taking this into account, Murphy and Cleveland (1995) proposed that acceptance

of performance appraisal by organizational members is a function of its process and

outcomes. The process refers to the extent to which employees perceive that the per-

formance rating reflects their true performance or contribution to their organization,

and also the extent to which employees perceive their supervisors make an informed

decision based on the information derived from the performance appraisals. In other

words, it is all about whether employees believe the appraisal process is valid or fair.

The outcomes of performance appraisal from the perspective of employees are fair

recognition or reward for their good performance from the organization they are work-

ing for, and motivation to improve their performance (Mayer & Davis, 1999; Roberson

& Stewart, 2006). It is not necessarily asking whether the merit pay system exists or

not. It is more about whether good performance by employees is recognized by the

agency or by the supervisors. In other words, perceptions of fairness and justice make

employees perceive performance appraisal as legitimate and necessary for their jobs

and performance improvement (Cawley et al., 1998). Greenberg (1986a, 1986b) also

proposed that employee acceptance of performance appraisal can be determined by the

extent to which employees perceive that their performance was fairly assessed and

linked to rewards by using the concepts of procedural and distributive justice.

Procedural justice refers to whether the performance appraisal is perceived as proce-

durally fair and valid, whereas distributive justice refers to whether the amount of

rewards for good performance is equitable (Gabris & Ihrke, 2000; Greenberg, 1986a ).

Gabris and Ihrke (2000) noted, “Central to employees’ acceptance of performance

appraisal is whether the system deployed is seen as procedurally fair and valid to

recipient employees” (p. 42). Reinke (2003) also defined employees’ acceptance of

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

6 Review of Public Personnel Administration

performance appraisal as “the extent to which the employee believes the process ade-

quately evaluates his or her performance and rewards good performance” (p. 29).

In this article, following the definition suggested by Murphy and Cleveland (1995),

Gabris and Ihrke (2001), and Reinke (2003), performance appraisal acceptability is

defined as employee perceived procedural and distributional justice related to the per-

formance appraisal process.1 The next section proposes key organizational factors that

help foster employee acceptance of a performance appraisal system using various

theoretical lenses.

Fostering Employee Acceptance: Purpose and Relational

Exchange

There are two major purposes of performance appraisal—evaluation and development

(Meyer et al., 1965; Moussavi & Ashbaugh, 1995). Evaluation is used for making

decisions on pay increases, promotions, transfers, and so on, whereas development is

for providing feedback aimed at coaching and developing employee capacity. In the

same vein, Reinke (2003) distinguished two major purposes of performance appraisal

as developmental approaches (development) and summative approaches (evaluation).

Reinke explained,

while the developmental approaches focus on enhancing employee performance by

identifying opportunities for employee growth and marshalling organizational resources

to support that growth, summative approaches are judgmental in nature and are explicitly

linked to extrinsic rewards such as promotions or pay. (p. 23)

Cognitive evaluation theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan, Mims, & Koestner, 1983)

explains that when external events, such as performance appraisal, provide informa-

tional feedback regarding employee competence and directions for the purpose of

increasing employee competence at their jobs, the intrinsic motivation of employees

can be enhanced. Adler and Borys (1996) provided a theoretical framework about

employee attitudes toward work formalization, and suggest that work practice can be

interpreted and perceived differently by employees (as either coercive or enabling),

depending on “ . . . the attributes of the type of formalization with which they are con-

fronted” (p. 66). They argued that when work practice focuses on managerial compli-

ance, which is characterized as “command and control centered,” employees will

experience it as coercive; however, when work practice is focused on guiding and

coaching employees, such as identifying their development needs so that they can

master their tasks, they will perceive it as enabling. Under the enabling formalization,

both employees and supervisors will view any deviance or problems derived as needs

for repair or opportunities for learning rather than as weaknesses or threats. Therefore,

when performance appraisal plays a role in providing employees with needed guid-

ance or coaching for improvement, positive attitudes toward performance appraisal by

employees are expected. This is consistent with the view of Wouters and Wilderon

(2008) that too much emphasis on the evaluation function of performance measure-

ment might crowd out the potential of its enabling function, and result in the

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 7

perception of performance measurement by employees as coercive and punitive.

However, employees can perceive the use of performance appraisal for a development

function as a constructive and enabling type of formalization.

Daley (1992) also noted that “developmental appraisal would go a great way in

driving out the fear engendered by the incorrect or abusive application of the judgmen-

tal appraisal” (p. 45). More interesting evidence is found in the study by Roberts

(1998). Two contrasting views are observed in his study : while one participant noted,

“Performance appraisal is a tool to intimidate and dominate employees” (p. 302), other

participants—who experience it as a system where employee input and participation is

encouraged—perceived it as helpful for their development. In addition, when perfor-

mance appraisal is mainly used for evaluation for personnel decisions such as promo-

tion, it is more likely to be subject to supervisor’s inter-personal relations or their

manipulations. Therefore, it is likely to be perceived as procedurally unfair by employ-

ees (Cardy & Dobbins, 1994). On the other hand, when performance appraisal has

developmental components, it is more about intra-personal comparisons (for develop-

ing an individual’s own actions or career plans) rather than inter-personal compari-

sons, resulting in a positive reaction by employees associated with performance

appraisal. Boswell and Boudreau (2000) empirically examined this issue in a survey

of employees of a production equipment facility, and find that employees are more

satisfied with performance appraisal when it is used for developmental purposes, such

as providing constructive suggestions and identifying training needs. Some studies

suggest that it should be viewed with caution, because when performance appraisal is

used to serve multiple purposes at the same time, it may result in more negative atti-

tudes and outcomes, such as inaccurate ratings and feedback (Boswell & Boudreau,

2002; Dorfman, Stephan, & Loveland, 1986; Murphy & Cleveland, 1995). However,

what is suggested in this article is the relative emphasis on developmental purpose

over evaluation purpose.

Despite the practical importance of the developmental use of performance appraisal,

most of previous studies have been conducted in the private sector setting, whereas

fewer empirical studies have been conducted in public sector organizations. The

developmental approach to performance appraisal may also shed light on research

about the relationship between pay-for-performance and public sector employee moti-

vation. Public service motivation literature argues that there can be a detrimental effect

of pay-for-performance on public sector employees who are more likely to be intrinsi-

cally motivated (Alonso & Lewis, 2001; Bright, 2005; Kellough & Lu, 1993; Pearce

& Perry, 1983; Perry & Wise, 1990). As Daley (1992) pointed out, developmental use

of performance appraisal can contribute to an employees’ intrinsic motivation because

it implies that the organization values the employees’ contribution; the organization

facilitates their intrinsic motivation by providing constructive feedback and making

their work interesting, even though “developmental opportunities may entail present

or potential extrinsic rewards” (p. 136). Moynihan (2008) also suggested the impor-

tance of having learning forums where organizational members can jointly examine

performance information through interactive dialogue and develop robust interpreta-

tions on performance feedback. Therefore, it is plausible to suggest that higher levels

of acceptance are anticipated when the appraisal system enhances motivation and

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

8 Review of Public Personnel Administration

development (Daley, 1992; Moussavi & Ashbaugh, 1995; Wouters & Wilderon, 2008).

Developmental use of performance appraisal is conceptualized as the extent to which

employees perceive performance appraisal plays a role in providing them with needed

guidance or coaching for performance improvement (Reinke, 2003).

Hypothesis 1a: When employees perceive performance appraisal is being used for

their development, they are more likely to have a higher acceptance of the proce-

dural fairness of the appraisal process.

Hypothesis 1b: When employees perceive performance appraisal is being used for

their development, they are more likely to have a higher acceptance of distribu-

tional fairness of the appraisal process.

The Leader–Member Exchange theory holds that the relationship between supervi-

sors and subordinates is a reciprocal social exchange process. Settoon, Bennett, and

Liden (1996) noted, “High-quality exchange relationships create obligations for

employees to reciprocate in positive, beneficial ways” (p. 219). As supervisor–

employee interaction occurs in the performance appraisal process, performance

appraisal should be affected by the quality of the supervisor–employee relationship.

When employees gain constructive performance feedback or identify areas of improve-

ment through extensive discussion with their supervisor in the performance appraisal

session, employees are more likely to reciprocate by expressing their commitment,

loyalty, and positive attitudes in return (Eisenberger, Fasolo, & Davis-LaMastro,

1990). Erdogan (2002) argued that, as performance appraisal involves ongoing inter-

action between supervisors and subordinates, the quality of the supervisor–subordi-

nate relationship affects how employees perceive procedural justice. Elicker, Levy,

and Hall (2006) conducted a survey of employees of a large petrochemical company

and found that employees who are in high-quality supervisor–employee relationships

respond favorably to performance appraisal. Reinke (2003) also suggested, based on

the results of the survey of 651 employees of a suburban county in Georgia, that the

trust between employees and supervisors is a strong predictor of their acceptance of

the process. Drawing on the studies of Leader–Member Exchange (Erdogan, 2002;

Liden & Graen, 1980; Settoon et al., 1996), the quality of supervisor–subordinate

relationship is defined as the degree of trust between supervisors and employees in

their interactions.

Hypothesis 2a: A high-quality supervisor–employee relationship is positively

associated with employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of its per-

ceived procedural fairness.

Hypothesis 2b: A high-quality supervisor–employee relationship is positively

associated with employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of its per-

ceived distributional fairness.

Participation in developing performance standards or performance goal setting can

positively affect employee acceptance of performance appraisal. Participation in the

appraisal process allows employees to voice concerns about its process or its outcome

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 9

without regard to its influence. Folger, Konovsky, and Cropanzano (1992) emphasized

that three principles must be followed in order for performance appraisal to be a fair

process: adequate notice, a fair hearing, and judgment based on evidence. They sug-

gested that by affording employees an opportunity for their inputs to be considered

when developing standards, their perceived procedural justice will be enhanced.

Roberts (2003) also asserted that by participating in performance appraisal goal

setting and standard development, perceived ownership of the performance appraisal

by employees is fostered, resulting in employee confidence in performance appraisal

and higher acceptance. He further noted that “[C]lear and specific standards of perfor-

mance are major elements of a valid and reliable performance appraisal system” (p.

91).

Daley (1992) contended that through participation, employees can address their

concerns and get a chance to clarify any misunderstandings. Cawley et al. (1998) fur-

ther contended that when participation in performance appraisal is “value expressive,”

meaning that employees perceive it as a chance to have a voice in the process without

regard to its final decisions or its effect on the outcomes, employees’ acceptability

becomes higher. Durant, Kramer, Perry, Mesch, and Paarlberg (2006) also suggest that

employee participation in joint-decision making is likely to contribute to affective

reactions by employees to the organization or to the decision-making process. By par-

ticipating in the performance appraisal process, employees can not only refute or chal-

lenge performance appraisal decisions that they disagree with but may also express

their concerns about decisions unfavorable to their status in an organization.

Participation in goal and standard setting implies that employees can influence the

performance appraisal process and the decisions made, and also share power with

supervisors. Allowing employees to engage in goal and performance standard setting

implies that supervisors and employees agree on the importance of collaborative

efforts to share knowledge about developing better measures, understanding the con-

texts, and solving emergent problems (deLancer Julnes, 2001). Employee participa-

tion in performance appraisal standard and goal setting is defined as the extent to

which employees have experiences in participating in their performance standards or

goals setting. We posit the following:

Hypothesis 3a: Employee participation in performance appraisal standard and goal

setting is positively associated with employee acceptance of performance appraisal

in terms of procedural justice.

Hypothesis 3b: Employee participation in performance appraisal standard and

goal setting is positively associated with employee acceptance of performance

appraisal in terms of distributional justice.

As Fernandez and Moldogaziev (2013) noted, when employees are granted

authority in regard to the work process, they are encouraged to come up with inno-

vative ideas without fear of punishment. Therefore, to have an honest and sincere

performance appraisal session between supervisors and employees, employees

should be empowered to modify or challenge their supervisor’s decision if it is not

based on what they consider to be correct information. Any bias in the decisions

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

10 Review of Public Personnel Administration

employees might observe as caused by a hierarchical relationship between these two

parties may affect their perceived procedural or distributional justice (Folger, 1987). In

addition, referent cognitions theory (Folger, 1987) explained that when employees

perceive that their outcomes could have been better, but their expected outcomes based

on the performance appraisal decisions are less than that, the difference will likely

make employees dissatisfied. However, when employees participate in the process,

and when employees are empowered to voice their concerns, their willingness to

accept the outcome will be increased because their input is considered in the process

(Potter, 2006). Carson, Cardy, and Dobbins (1991) asserted that when the evaluation

of their performance is perceived to be outside of their control, it may negatively affect

employee trust. Furthermore, there has been a similar consensus as to the positive

motivational effect of employee empowerment—that it is positively related to

employee motivation, commitment, perceptions of control, and other positive job atti-

tudes (Park & Rainey, 2008; Rainey, 2003). Instrumental theories of procedural justice

also suggest that when organizational members are given the opportunity to express

themselves in the process in an effort to control the outcomes, their expectation for

better outcomes will be enhanced and accordingly their perceptions of procedural jus-

tice will be enhanced as well because “it increase[s] the probability of either favorable

outcomes or equitable outcomes” (Lind, Kanfer, & Earley, 1990, p. 954). Therefore,

we hypothesize a positive relationship between employee empowerment and employee

acceptance of performance appraisal. In this article, following the study of Petter,

Byrnes, Choi, Fegan, and Miller (2002) and Kim and Rubianty (2011), employee per-

ceived empowerment is defined as the extent to which employees are allowed to voice

their concerns over the process and the degree to which they are involved in decision-

making processes.

Culbert and McDonough (1986, p. 182) suggested that “empowerment is the key to

understanding trust and trusting relationships in an organization.” In addition,

Dierendonck and Dijkstra (2012) noted “the extent to which [employees] feel empow-

ered at work affects the way they will be treated in return” (E. 14). When employees

are empowered in their jobs, they are more likely to view their leaders as fair and

trustworthy. In other words, when managers practice empowering leadership, it sig-

nals their trust in their employees. In return, employees may build trust in their man-

ager. Gomez and Rosen (2001) empirically prove the positive relationship between

employee perceptions of a high-quality relationship with their managers and their per-

ception of meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact, or in other words,

perceived empowerment.

Thus, it is plausible to assume that employee empowerment will directly and posi-

tively affect employee acceptance of the appraisal system, and also indirectly affect

employee acceptance of the appraisal process through positively influencing the qual-

ity of supervisor–employees relationships. Hence,

Hypothesis 4a: Employee perception of empowerment is positively associated with

employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of procedural justice, and

Hypothesis 4b: Employee perception of empowerment is positively associated with

employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of distributional justice.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 11

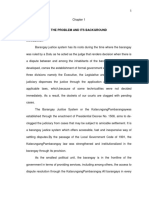

Purpose: Developmental

Use of Performance

Appraisal

Employees’ Acceptance

of Performance

Employees’ Participation in Appraisal

Performance Standard Procedural Justice

Setting

Distributional Justice

Supervisor-Subordinate

Relationship Quality

Perceived Empowerment

Figure 1. Conceptual framework: Antecedents to employees’ acceptance of performance

appraisal.

Hypothesis 5a: When employee perception of empowerment is higher, the rela-

tionship between quality of supervisor–employee relationship and employee accep-

tance of performance appraisal in terms of procedural justice will be greater, and

Hypothesis 5b: When employee perception of empowerment is higher, the rela-

tionship between quality of supervisor–employee relationship and employee accep-

tance of performance appraisal in terms of distributional justice will be greater.

Figure 1 provides an overview of these factors.

Data, Measures, and Methods

Our study used data from the 2005 Merit Principles Survey that was administered by

the U.S. Merit System Protection Board (MSPB). Among the randomly selected sam-

ple of 74,000 employees in 24 federal agencies, in total 36,926 full-time, permanent,

non-seasonal federal employees completed the survey and its response rate was 50%.

All the survey items are measured using 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from

strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Dependent Variable: Employees Acceptance of Performance Appraisal

System

Building on Gabris and Ihrke’s (2000) theoretical framework and measurement scales,

this article measures the extent to which employees accept performance appraisal sys-

tems using two constructs—procedural justice and distributional justice. As discussed

above, procedural justice deals with the process of performance appraisal, whereas

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

12 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Table 1. Principal Component Factor Analysis Results (Varimax Method): Dependent

Variables.

Items Factor 1 Factor 2

Procedural justice

I understand the basis for my recent performance rating. .8329 .1843

The standards used to appraise my performance are .8307 .2385

appropriate.

I understand what I must do to receive a high performance .8020 .2536

rating.

Objective measures are used to evaluate my performance. .7331 .3561

Distributional justice

Recognition and rewards are based on performance in my .4006 .6710

work unit.

I understand how my pay relates to my job performance. .3121 .5526

My organization takes steps to ensure that employees are .2232 .8485

appropriately paid and rewarded.

If I perform well, it is likely I will receive a cash award or pay .2170 .8231

increase.

distributional justice is about its outcomes. Procedural justice and distributional justice

are measured using survey items, adapted from the study of procedural and distribu-

tional justice (Gabris & Ihrke, 2000; Kim & Rubianty, 2011; Rubin, 2009; Rubin &

Kellough, 2012). Using principal components analysis with varimax rotation, eight

items were factor analyzed, and derived two factors—procedural justice and distribu-

tional justice. Procedural justice is measured using four items and its alpha score is

.8263, indicating high reliability, whereas distributional justice is measured using four

items and its alpha score is .7927, also indicating a high reliability (see Table 1).

Independent Variables

According to Daley (1992) and Murphy and Cleveland (1995), developmental use of

performance refers to employees’ perceived use of performance appraisal for provid-

ing constructive suggestions and identifying training needs. Building on their frame-

work, we measure developmental use of performance appraisal using five items,

including (a) I have sufficient opportunities (such as challenging assignments or proj-

ects) to earn a high performance rating; (b) My supervisor provides constructive feed-

back on my job performance; (c) Discussions with my supervisor about my performance

are worthwhile; (d) My supervisor provides coaching, training opportunities, or other

assistance to help me improve my skills and performance; and (e) My supervisor pro-

vides timely feedback on my job performance. All five items were loaded onto one

factor and its alpha score is .8846, indicating high reliability.

Leader–Member Exchange theory (Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Liden & Graen, 1980)

describes the quality of the supervisor–employee relationship as the degree of trust

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 13

between supervisors and employees in the interaction or perceived contribution of

each party to the exchange of mutual goals. Following this definition, the quality of the

supervisor–employee relationship in the appraisal process is measured using three

items, including (a) I trust my supervisor to fairly assess my performance and contri-

butions; (b) I trust my supervisor to clearly communicate conduct expectations; and

(c) My supervisor is held accountable for rating employee performance fairly and

accurately. All five items are adapted from Cho and Lee (2011) and Park (2012) and

are loaded onto one factor and its alpha score is .9196.

Also, adapted from Roberts (2003), employee participation in the development of

performance standards has been measured with a single questionnaire item: “I partici-

pate in setting standards and goals used to evaluate my job performance.” Employee

perceived empowerment is defined as “the degree to which employees can voice their

concerns over the process.” It is measured using three items drawn from Kim and

Rubianty (2011), including (a) “I am treated with respect at work,” (b) “I am able to

openly express concerns at work,” and (c) “My opinions count at work.” The reliabil-

ity of this scale is .9346.

The interaction term for the quality of the supervisor–employee relationship and

employee perceived empowerment is included after mean-centering these two con-

stituent variables to mitigate the potential problem of multicollinearity (Jaccard, Wan,

& Turrisi, 1990).

Control Variables

Employment attributes and demographic attributes are included as control variables

that may influence employee acceptance of performance appraisal. We have assumed

that there might be differences in employee acceptance, depending on their employ-

ment or demographic attributes. Employment attributes include workplace, supervi-

sory status, salary, tenure in federal government, tenure in the current agency,

education level, and union membership. Location is a dichotomous variable, where

1 indicates employees are working in headquarters and 0 indicates employees are

working in a field office. Supervisory status is also a dichotomous variable that cap-

tures whether the respondents have a position of supervisor or higher (=1) or not

(=0). Tiffin and McCormick (1962) noted that unionized employees are more likely

to have unfavorable attitudes toward merit ratings because the emphasis is placed

more on seniority than merit ratings, which may entail subjective judgment—espe-

cially when it is related to personnel decisions. Iverson (1996) also found that there

is a negative relationship between union membership and employee acceptance of

organizational change and employee commitment. To control its possible effect,

union membership is included using a survey item as a dichotomous variable where

1 indicates employees who pay union member membership dues and 0 indicates

employees who do not pay union membership dues. Demographic attributes include

gender (male = 1, female = 0), education, and age. Descriptive statistics are pre-

sented in the appendix.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

14 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Findings

A multiuple hierarchical regression was employed to examine the relationship between

three independent variables and the dependent variable. Model 1 tested the relation-

ship between the control variables and the dependent variable, whereas Models 2, 3,

and 4 tested the relationship between each independent variable and the dependent

variable. The last model examined the moderator relationship by regressing employee

acceptance of performance appraisal on the quality of the supervisor–employee rela-

tionship, employee participation in performance standard setting, employee perceived

empowerment, controls and the interaction term—which is denoted as the Quality of

Supervisor–Employee Relationship × Empowerment. The advantage of using a hierar-

chical linear regression is that the vulnerability of federal government data to a cluster-

ing effect can be addressed (Yang & Kassekert, 2010). Moreover, using a hierarchical

regression is advantageous to this study in that “the interactive effect of X1 × X2 on Y

is assessed only after the additive effects of XI and X2 have been partialed out” as

Friedrich (1982, p. 802) emphasizes. The results from the regression analyses are

reported in Tables 2 and 3 below. The variance inflation factor (VIF) test for multicol-

linearity in both models shows the average VIF value is less than 2.5, indicating that

there is not a severe problem of multicollinearity.2 The Breusch Pagan test indicated

the presence of heteroscedasticity, requiring the application of robust standard errors.

The findings indicate that all proposed hypotheses are supported when controlling for

employment and demographic attributes.

Developmental use of performance appraisal. The results show that, when controlling

for other factors, developmental use of performance appraisal is significantly and pos-

itively related to employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of both dis-

tributive and procedural justice with, and independent of, the moderating effect of

employee perceived empowerment. Developmental use of performance appraisal has

a positive and significant effect on both employees’ acceptance of performance

appraisal in procedural justice (β coefficient = .27, ***p < .01) and distributive justice

(coefficient = .26, ***p < .01), supporting Hypotheses 1a and 1b.

It seems reasonable to assume that, in a constructive organizational culture where

identifying training needs and development opportunities are valued, supervisors who

rate employee performance are more likely to follow fair procedures compared with a

culture wherein favoritism is prevalent (Erdogan, 2002). In other words, when perfor-

mance appraisal is used more for improving employee capacity building and achieve-

ment, it will positively affect employee intrinsic motivation and it will be perceived as

less threatening by employees (Cooke & Szumal, 1993; Erdogan, 2002). However,

even when performance appraisal is used for developmental purposes, employee

acceptance of performance appraisal regarding distributional justice can be low. This

is possible when employees overestimate their contributions to the organization or

when employees expect lower rewards compared with their efforts due to the resource

constraints of public organizations.

The positive relationship between developmental use of performance appraisal and

employee acceptance of procedural justice and distributional justice supports the

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 15

Table 2. Regression Results Predicting Employees’ Acceptance of Performance Appraisal:

Procedural Justice.

Coefficients

Variables Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

Main variables

Developmental use .273*** .273*** .273*** (.01)

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) .189*** .189*** .189*** (.01)

Empowerment .117*** .117*** .117*** (.01)

Participation .294*** .294*** .294*** (.00)

Interaction effect

LMX × Empowerment .002 .002

Control variables

Location .040*** −.000 −.000 −.000 (.01)

Supervisory status .137*** −.020** −.020** −.020** (.01)

Union −.220*** .009 .009 .009 (.01)

Gender −.086*** −.082*** −.082*** −.082*** (.01)

Tenure in federal government −.004*** −.002** −.002** −.002** (.00)

Tenure in agency .003*** −.000 −.000 −.000 (.00)

Age −.001 .001 .001 .001 (.00)

Education −.027*** −.012*** −.012*** −.012*** (.00)

Salary .001*** .000 .000 .000 (.00)

Constant .088** −.915*** −.915*** −.915***

Observation 28,352 27,704 27,704 27,704

R2 .015 .591 .591 .591

Adjusted R2 .015 .591 .591 .591

Note. Steps 1 to 3 report results of OLS regression, whereas Step 4 reports robust regression results.

Robust standard errors are given in parentheses. OLS = ordinary least squares.

*p < .1. **p < .05. ***p < .01.

concept of enabling aspects of performance appraisal and its positive effect on

employee acceptability of performance appraisal (Adler & Borys, 1996; Daley,

1992). This finding is consistent with Boswell and Boudreau’s (2000) study of

employee reactions to performance appraisal at a production equipment facility. They

found that developmental performance appraisal is positively associated with

employee outcomes, such as commitment or their satisfaction with the appraisal pro-

cess. From the motivational perspective of employees, this finding is not surprising

because compared with judgmental approach, developmental approach is more about

enhancing employee motivation by adding value to them (Daley, 1992). The positive

relationship between developmental use of performance appraisal and employee

acceptance supports the concept of enabling aspect of performance appraisal and its

positive effect on employee acceptability of performance appraisal (Adler & Borys,

1996; Daley, 1992).

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

16 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Table 3. Regression Results Predicting Employees’ Acceptance of Performance Appraisal:

Distributive Justice.

Coefficients

Variables Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

Main variables

Developmental use .265*** .261*** .261*** (.01)

Leader-Member Exchange .144*** .157*** .157*** (.01)

Empowerment .223*** .236*** .236*** (.01)

Participation .123*** .121*** .121*** (.00)

Interaction effect

LMX × Empowerment .034*** .034*** (.00)

Control variables

Location .108*** .102*** .101*** .101*** (.01)

Supervisory status .226*** .089*** .0887*** .089*** (.01)

Union −.274*** −.085*** −.0851*** −.085*** (.01)

Gender −.027** −.035*** −.034*** −.034*** (.01)

Tenure in federal government .001* .005*** .005*** .005*** (.00)

Tenure in agency .004*** .000 .000 .000 (.00)

Age −.000 .002*** .002*** .002*** (.00)

Education .005 .017*** .016*** .016*** (.00)

Salary .002*** .002*** .002*** .002*** (.00)

Constant −.398*** −.815*** −.821*** −.821***

Observations 29,475 28,792 28,792 28,792

R2 .054 .469 .47 .47

Adjusted R2 .0539 .4683 .4699 .591

Note. Steps 1 to 3 report results of OLS regression, whereas Step 4 reports robust regression results.

Robust standard errors are given in parentheses. OLS = ordinary least squares.

*p < .1. **p < .05. ***p < .01.

Quality of supervisor–employee relationship. In both models, the quality of the supervi-

sor–employee relationship turns out to positively affect employee acceptance of per-

formance appraisal, supporting Hypotheses 2a and 2b. The results confirm the

previous argument that a high quality of supervisor–employee (rater–ratee) relation-

ship matters for positive reactions of employees to performance appraisal, including

their acceptability (Eisenberger et al., 1990; Elicker et al., 2006). As Erdogan (2002)

pointed out, if supervisors form high-quality relationships with their employees

based on factors related to employee work performance, within the context of an

interactive relationship with them, employee perceptions of procedural and distribu-

tional justice would increase. It is also consistent with Gabris and Ihrke’s (2000)

view that a low-quality supervisor–employee relationship is highly likely to be neg-

atively associated with a perceived lack of legitimacy of performance appraisal by

employees.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 17

Participation in performance standard setting. We expect that participation in perfor-

mance standard setting would be positively associated with employee acceptance of

performance appraisal. The results on Tables 2 and 3 attest this positive relationship at

the .01 level, in support of Hypotheses 3a and 3b. This result is consistent with Rob-

erts’s (2003) conclusion that employee participation in developing performance stan-

dards positively contributes to heightening employee acceptance of performance

appraisal. By affording an opportunity to have a voice in the appraisal process,

employees become more confident in the fairness of the appraisal process, resulting in

a cultivation of their acceptance of performance appraisal (Daley, 1992; Roberts,

2003).

Perceived empowerment. Although the importance of empowerment is widely acknowl-

edged, there is scant research that empirically examines the effect of empowerment on

attitudinal reaction of employees to performance appraisal, especially employee

acceptance of performance appraisal. Our results provide an interesting finding, in that

empowerment turns out to have a positive impact on employee acceptance of perfor-

mance appraisal in terms of distributive justice (β coefficient = .24, ***p < .01) and

procedural justice (β coefficient = .12, ***p < .01). It appears to have a stronger impact

on employee perceptions of distributive justice compared with its effect on procedural

justice. These results provide supporting evidence for instrumental theories of proce-

dural justice in that when employees are given opportunities to express their views or

concerns, they will believe that their voices can encourage management to make better

decisions and provide better outcomes.

This also may be supplementary evidence supporting “Referent Cognitions Theory”

(Folger, 1987). As empowered employees can rebut performance appraisal decisions

that they disagree with, or rebut decisions that are made based on the wrong informa-

tion, the difference between their expected outcome and the outcome they actually

receive can be reduced, resulting in employees’ perceived procedural justification.

Moreover, compared with work settings where evaluations of performance are beyond

employee control and passive acceptance of performance rating is required, when

employees are empowered to engage in the decision-making process, refute decisions,

and have a voice in the process, their perceived justice in the appraisal process is

enhanced.

Interaction of quality of supervisor–employee relationship and empowerment. Tables 2 and

3 show that the interaction effect of relationship quality of supervisor and employee—

and empowerment on employees’ acceptance of performance appraisal for distributive

justice—is significant at the β = .045, p < .01 level. The results provide partial support

for Hypothesis 5b. The interaction effect was expected to positively relate to employee

acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of procedural justice as well, but Hypoth-

esis 5a was not supported. However, small coefficient on the interaction term and little

change in adjusted R2 indicate that the moderating effect on employee acceptance of

performance appraisal is modest or unsubstantial, contrary to our expectations. To better

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

18 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Figure 2. Interaction effect of relationship quality and empowerment on employee’s

acceptance: Distributive justice.

examine the interaction effect, the marginal effect of the quality of the supervisor–

employee relationship (contingent on the perceived level of empowerment) is calcu-

lated and plotted when empowerment is equal to its mean value, which is its mean

value plus/minus one standard deviation (see Figure 2). The results show that the

effect of relationship quality between supervisor and employee on the acceptance of

the employee in terms of distributional justice depends on employee perceptions of

empowerment.3 In other words, when employees perceive they are empowered in their

work process, the effect of the quality of the relationship between supervisor and

employees on employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of distribu-

tional justice will be greater. Even when employees develop trusting relationships with

their supervisors, it does not necessarily mean that they trust in their supervisor’s

capacity to effectively supervise the appraisal process. In other words, unless their

supervisor exhibits the capacity to effectively supervise employees and effectively

assess their performance, employee views of performance appraisal remain negative.

Therefore, this positive interaction effect of empowerment and the quality of relation-

ship between employees and supervisors may imply that by being empowered,

employees can address their concerns regarding their supervisors’s appraisal perfor-

mance, such as the way the appraisal session was conducted or the way of supervising.

In this way, when empowered, the effect of the quality of the relationship between

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 19

supervisor and employees on employee acceptance of performance appraisal can be

maximized. The interaction effect on employee acceptance of performance appraisal

in terms of procedural justice was not significant but in the expected direction. Given

very little explanatory value that the interaction term added to the model, the relative

influence is difficult to predict but its positive effect that appears in the regression

results as well as the marginal plot provides partial support for the Hypothesis 5b.

Employment and demographic attributes. Employment and demographic attributes pro-

vide mixed findings. Employees who hold a supervisory or higher position, who have

stayed long in federal government, or who work at headquarters have higher accep-

tance of performance appraisal in terms of distributive justice. Age, education, and

salary are positively associated with employee acceptance of performance appraisal in

terms of distributive justice. On the other hand, employees who hold non-supervisory

positions, and those who hold union membership, have higher acceptance of perfor-

mance appraisal in terms of procedural justice. Union membership is positively related

to employee acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of procedural justice,

whereas it is negatively related to distributive justice, supporting previous research by

Tiffin and McCormick (1962). This finding is not surprising, as employees who have

union membership prefer to be rewarded based on their seniority rather than merit, and

therefore may have negative attitudes toward the distributional component of perfor-

mance appraisal. On the other hand, it appears that employees who have union mem-

bership are more likely to have higher acceptance of performance appraisal in terms of

procedural justice. It makes sense in that federal employees are not required to join a

union; that is, they voluntarily join unions, and by joining unions they might have

more procedural protections from organization.

Concluding Discussion

This study examined the factors that foster employee acceptance of performance

appraisal. It is important because when employees have limited buy-in to performance

appraisal, in terms of its purpose and its value, the performance appraisal system may

well be ineffective. The path to improving effectiveness, and gaining the support of

employees, is anchored in enhancing employee perceptions of the importance of the

appraisal process and its usefulness in developing their career building capacities.

Building on the theoretical frameworks of Greenberg (1986a, 1986b) and Gabris and

Ihrke (2000), employee acceptance of performance appraisal is operationalized in

terms of procedural justice and distributional justice in performance appraisal. The

empirical results of this study provide supporting evidence for the hypotheses in four

key areas. First, the developmental use of performance appraisal is found to positively

contribute to heightening employee acceptance of that process. As performance

appraisal contains extrinsic motivational components and is linked to extrinsic rewards

such as a promotion or salary increase, when it is used for public employees who are

more likely to be motivated by intrinsic factors, decreasing employee intrinsic motiva-

tion or a negative reaction from employees may be expected (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

20 Review of Public Personnel Administration

This finding, however, implies that the extrinsic components of performance appraisal

do not necessarily crowd out the intrinsic motivation of employees, and its relation-

ship can be changed depending on the relative difference of emphasis on development

over evaluation. This finding also implies that too much emphasis on evaluation at the

expense of development can demotivate employees. This brings more resistance to

performance appraisal, while more emphasis on development and learning can foster

employee acceptance of performance appraisal and increase their satisfaction with it.

Second, as performance appraisal occurs in a context where employees and super-

visors interact with each other, the quality of relationship between these two parties is

expected to be an important factor for fostering employee acceptance of performance

appraisal, and our findings support this relationship. No matter how valid and accurate

the performance standards are, the absence of employee trust in their performance

rater, that is, the supervisor, would negatively affect employee perceptions of perfor-

mance appraisal. A trustworthy relationship between the two parties (employee and

supervisor) is found to be positively associated with employee acceptance of perfor-

mance appraisal. In addition, employee participation in performance standard setting

is positively associated with employee acceptance. Finally, this study concludes that

employee perceived empowerment positively affects both employee acceptance and

the quality of the relationships they have with their supervisors, resulting in moderat-

ing the impact of quality of relationship on employee acceptance of performance

appraisal.

We believe this study offers a new perspective on how to make public employees

embrace performance appraisal or pay-for-performance systems by explaining how

employee acceptance of such appraisals can work in harmony with the intrinsic moti-

vation of public employees, and can provide supporting evidence for the effectiveness

of enabling formalization (Adler & Borys, 1996). This study also contributes to the

previous literature on both performance appraisal and employee acceptance of perfor-

mance appraisal by providing empirical evidence from a survey of federal employees.

In addition, focusing on employee cognitive reactions to public performance appraisal

as conducted in this study, in the public sector setting, complements the wealth of stud-

ies on the organizational level of performance measurement. This study sheds light on

the necessity of further study of these issues in this context.

This study has some limitations. As all the variables in this study use measures

from a self-administered survey, it should be noted that common-source bias exists in

this study. However, as indicated by other empirical studies using self-reported sur-

veys, such as the National Administrative Studies Project (NASP-II) and the Merit

Principles Survey, the existence of the common-source bias does not necessarily inval-

idate the findings; rather, it may marginally attenuate or inflate the relationship identi-

fied herein (Crampton & Wagner, 1994; Alonso & Lewis, 2001 ).

Another limitation is that our analysis is based on cross-sectional secondary data

that may limit our ability to make causal inference. This study does not consider the

years of performance appraisal experience employees have because it uses secondary

data that does not address this issue. It is possible to expect that longer experience

participating in a performance appraisal process may bring different attitudinal

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 21

reactions and acceptance levels. Future study should consider employing longitudinal

research design or incorporating time variables in the analysis.

Moreover, as this study deals with the human aspects of performance appraisal,

more precise analysis could have been conducted had the authors interviewed federal

employees regarding this issue. As Rubin (2011) noted, “Performance appraisal is a

key tool for assuring the accountability of public servants” (p. 24). Without addressing

employee acceptance of performance appraisal, it would be risky to blame the perfor-

mance appraisal process for its ineffectiveness in bringing about performance

improvement.

Last, even though employees are given opportunity to participate in their perfor-

mance standard setting, unless they understand how their work is related to achieving

agency goals, the true ownership of the agency’s goals and objectives cannot be made.

Also, the lack of clarity concern tasks or goal clarity on the part of employees may

harm their acceptance of performance appraisal. Future study can expand the current

understanding of employee acceptance of performance appraisal by incorporating

those two factors.

Appendix

Descriptive Statistics

Variable Observations M SD

Procedural justice 33,226 0.00 1.00

Distributive justice 33,900 −0.00 1.00

Developmental use of performance appraisal 32,955 0.00 1.00

Supervisor–employees relationship quality 33,020 −0.00 1.00

Empowerment 35,591 −0.00 1.00

Participation in performance standard setting 34,857 3.36 1.20

Location (head = 1, field = 0) 31,562 0.25 0.44

Supervisory status 32,058 0.60 0.49

Union membership 31,838 0.12 0.32

Gender 31,707 0.59 0.49

Tenure in federal government 31,825 19.68 9.79

Tenure in agency 31,917 16.18 9.60

Age 31,118 49.07 8.76

Education 31,730 2.94 1.28

Salary 31,266 84.09 41.75

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

22 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of

this article.

Notes

1. Employee acceptability of the appraisal process is a concept that is very similar to that of

their satisfaction with the process. However, it should be distinguished from employee

acceptance of the process. Employee satisfaction with the process means that they are sat-

isfied with either the appraisal system or its ratings (Giles & Mossholder, 1990; Keeping

& Levy, 2000). Employee acceptability of the process goes beyond their satisfaction with

the process. It indicates the extent to which employees believe performance appraisal is a

valid and reliable process whose outcomes contribute to their job morale and performance,

which is more critical to the effectiveness of performance appraisal.

2. The variation inflation factors for all independent variables were less than 5.

3. When empowerment is high, the effect of relationship quality on employee acceptance

(distributional justice) is β = .472, p < .01, whereas when empowerment is low, the β is .37,

p < .01.

References

Adler, P. S., & Borys, B. (1996). Two types of bureaucracy: Enabling and coercive. Adminis-

trative Science Quarterly, 41, 61-89.

Alonso, P., & Lewis, G. B. (2001). Public service motivation and job performance evidence

from the federal sector. American Review of Public Administration, 31, 363-380.

Berman, E. M., Bowman, J., West, J., & Van Wart, M. R. (2006). Human resource management

in public service: Paradoxes, problems and processes (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Boswell, W. R., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). Employee satisfaction with performance appraisals

and appraisers: The role of perceived appraisal use. Human Resource Development Quar-

terly, 11, 283-299.

Boswell, W. R., & Boudreau, J. W. (2002). Separating the developmental and evaluative perfor-

mance appraisal uses. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16, 391-412.

Bright, L. (2005). Public employees with high levels of public service motivation who are they,

where are they, and what do they want? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 25,

138-154.

Cardy, R. L., & Dobbins, G. H. (1994). Performance appraisal: Alternative perspectives. Cin-

cinnati, OH: South-Western Publishing.

Carroll, S. J., & Schneier, C. E. (1982). Performance appraisal and review systems: The identi-

fication, measurement, and development of performance in organizations. Glenview, IL:

Scott Foresman.

Carson, K. P., Cardy, R. I., & Dobbins, G. H. (1991). Performance appraisal as effective mana-

gement or deadly management disease: Two initial empirical investigations. Group and

Organization Studies, 16, 143-159.

Cawley, B. D., Keeping, L. M., & Levy, P. E. (1998). Participation in the performance appraisal

process and employee reactions: A meta-analytic review of field investigations. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 83, 615-633.

Cho, Y. J., & Lee, J. W. (2011). Performance management and trust in supervisors. Review of

Public Personnel Administration, 32, 236-259.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

Kim and Holzer 23

Cooke, R. A., & Szumal, J. A. (1993). Measuring normative beliefs and shared behavioral ex-

pectations in organizations: The reliability and validity of the organizational culture inven-

tory. Psychological Reports, 72, 1299-1330.

Crampton, S. M., & Wagner, J. A. (1994). Percept-percept inflation in micro organizational

research: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79,

67-76.

Culbert, S. A., & McDonough, J. J. (1986). The politics of trust and organization empowerment.

Public Administration Quarterly, 10, 171-188.

Daley, D. M. (1992). Performance appraisal in the public sector: Techniques and applications.

Westport, CT: Quorum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human beha-

vior. New York, NY: Plenum.

deLancer Julnes, P. (2001). Does participation increase perceptions of usefulness? An evalua-

tion of a participatory approach to the development of performance measures. Public

Performance & Management Review, 24, 403-418.

Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Advanced Enginee-

ring Study.

Dickinson, T. L. (1993). Attitudes about performance appraisal. In Personnel selection and

ass-essment: Individual and organizational perspectives (pp. 141-161), Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A criti-

que and further development. Academy of Management Review, 11, 618-634.

Dierendonck, D., & Dijkstra, M. (2012). The role of the follower in the relationship between

empowering leadership and empowerment: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Applied

Social Psychology, 42(S1), E1-E20.

Dorfman, P. W., Stephan, W. G., & Loveland, J. (1986). Performance appraisal behaviors:

Supervisor perceptions and subordinate reactions. Personnel Psychology, 39, 579-597.

Durant, R. F., Kramer, R., Perry, J. L., Mesch, D., & Paarlberg, L. (2006). Motivating em-ploy-

ees in a new governance era: The performance paradigm revisited. Public Administration

Review, 66, 505-514.

Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organizational support

and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75,

51-59.

Elicker, J. D., Levy, P. E., & Hall, R. J. (2006). The role of leader-member exchange in the per-

formance appraisal process. Journal of Management, 32, 531-551.

Erdogan, B. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of justice perceptions in performance ap-

praisals. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 555-578.

Fernandez, S., & Moldogaziev, T. (2013). Using employee empowerment to encourage innova-

tive behavior in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory,

23, 155-187.

Fields, D. L. (2002). Taking the measure of work: A guide to validated scales for organizational

research and diagnosis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fletcher, C. (2001). Performance appraisal and management: The developing research agenda.

Journal of Occupational and organizational Psychology, 74(4), 473-487.

Folger, R. (1987). Distributive and procedural justice in the workplace. Social Justice Research,

1, 143-159.

Folger, R., Konovsky, M. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1992). A due process metaphor for perfor-

mance appraisal. Research in Organizational Behavior, 14, 129.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com at RUTGERS UNIV on January 18, 2015

24 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Friedrich, R. J. (1982). In defense of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations.

American Journal of Political Science, 26, 797-833.

Gabris, G. T., & Ihrke, D. M. (2000). Improving employee acceptance toward performance app-

raisal and merit pay systems: The role of leadership credibility. Review of Public Personnel

Administration, 20, 41-53.

Gaertner, K. N., & Gaertner, G. H. (1985). Performance-contingent pay for federal managers.

Administration & Society, 17, 7-20.

Giles, W. F., & Mossholder, K. W. (1990). Employee reactions to contextual and session com-

ponents of performance appraisal. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 371-377.

Gomez, C., & Rosen, B. (2001). The leader-member exchange as a link between managerial

trust and employee empowerment. Group Organization Management, 26, 53-69.

Greenberg, J. (1986a). Determinants of perceived fairness in performance evaluation. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 71, 340-342.

Greenberg, J. (1986b). The distributive justice of organizational performance evaluations. In

H.W. Bierhoff, R.L. Cohen, & J. Greenberg (Eds.), Justice in social relations (pp.337-352).

New York: Plenum Press .

Hedge, J. W., & Borman, W. C. (1995). Changing conceptions and practices in performance

appraisal. In A. Howard (Ed.), The changing nature of work (pp. 451-481). San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hedge, J. W., & Teachout, M. S. (2000). Exploring the concept of acceptability as a criterion for

evaluating performance. Group & Organization Management, 25, 22-44.

Iverson, R. D. (1996). Employee acceptance of organizational change: The role of organizatio-

nal commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 7, 122-149.

Jaccard, J., Wan, C. K., & Turrisi, R. (1990). The detection and interpretation of interaction

ef-fects between continuous variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behavioral

Research, 25, 467-478.

Keeping, L. M., & Levy, P. E. (2000). Performance appraisal reactions: Measurement, mode-

ling, and method bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 708-723.