Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Impact of Dreams of The Deceased On Bereavement: A Survey of Hospice Caregivers

Uploaded by

areesha naseerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Impact of Dreams of The Deceased On Bereavement: A Survey of Hospice Caregivers

Uploaded by

areesha naseerCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/235756432

The Impact of Dreams of the Deceased on Bereavement: A Survey of Hospice

Caregivers

Article in The American journal of hospice & palliative care · February 2013

DOI: 10.1177/1049909113479201 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

14 983

6 authors, including:

Scott T Wright Pei C Grant

University at Albany, The State University of New York Hospice & Palliative Care Buffalo

16 PUBLICATIONS 116 CITATIONS 35 PUBLICATIONS 317 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Scott T Wright on 04 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

American Journal of Hospice and Palliative

Medicine

http://ajh.sagepub.com/

The Impact of Dreams of the Deceased on Bereavement: A Survey of Hospice Caregivers

Scott T. Wright, Christopher W. Kerr, Nicole M. Doroszczuk, Sarah M. Kuszczak, Pei C. Hang and Debra L. Luczkiewicz

AM J HOSP PALLIAT CARE published online 28 February 2013

DOI: 10.1177/1049909113479201

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ajh.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/02/26/1049909113479201

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ajh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ajh.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Feb 28, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

Counseling/Pastoral Care

American Journal of Hospice

& Palliative Medicine®

The Impact of Dreams of the 00(0) 1-7

ª The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permission:

Deceased on Bereavement: A sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1049909113479201

Survey of Hospice Caregivers ajhpm.sagepub.com

Scott T. Wright, BA1, Christopher W. Kerr, MD, PhD1,

Nicole M. Doroszczuk, LMSW1, Sarah M. Kuszczak, BS1,

Pei C. Hang, PhD1, and Debra L. Luczkiewicz, MD1

Abstract

Many recently bereaved persons experience vivid and deeply meaningful dreams featuring the presence of the deceased that may

reflect and impact the process of mourning. The present study surveyed 278 bereaved persons regarding their own perspective of

the relationship between dreams and the mourning process. Fifty eight percent of respondents reported dreams of their deceased

loved ones, with varying levels of frequency. Most participants reported that their dreams were either pleasant or both pleasant

and disturbing, and few reported purely disturbing dreams. Prevalent dream themes included pleasant past memories or

experiences, the deceased free of illness, memories of the deceased’s illness or time of death, the deceased in the afterlife

appearing comfortable and at peace, and the deceased communicating a message. These themes overlap significantly with previous

models of bereavement dream content. Sixty percent of participants felt that their dreams impacted their bereavement process.

Specific effects of the dreams on bereavement processes included increased acceptance of the loved one’s death, comfort,

spirituality, sadness, and quality of life, among others. These results support the theory that dreams of the deceased are highly

prevalent among and often deeply meaningful for the bereaved. While many counselors are uncomfortable working with dreams in

psychotherapy, the present study demonstrates their therapeutic relevance to the bereaved population and emphasizes the

importance for grief counselors to increase their awareness, knowledge, and skills with regards to working with dreams.

Keywords

bereavement, dreams, tasks of mourning, hospice, grief, counseling, dreams of the deceased

Introduction deceased, and dreams in which the deceased communicates a

message to the dreamer. The variation between these models

The death of a loved one is among the most painful events a

may reflect the nature of dreams themselves, which are inher-

person can endure and one that almost all experience during ently as unique and diverse as those who dream them. These

their lifetime. The grief that follows is marked by challenges

models are also typically based on small samples using quali-

in adjustment extending across emotional, cognitive, physiolo-

tative methodologies, and there are limited quantitative studies

gical, social, and spiritual domains.1 The myriad of changes

pertaining to bereavement dreams. The literature suggests that

experienced during bereavement may also include vivid, mean-

bereavement dreams typically feature the presence of the

ingful dreams that often feature the deceased and reflect the

deceased, are highly vivid and emotionally laden, and represent

grieving process.1-4

a source of meaning for the bereaved.

Several surveys have provided evidence that dreams of

Given the prevalence and emotional poignancy of dreams of

deceased loved ones are highly prevalent among the the deceased, these dreams are likely related to the process of

bereaved.5-7 Although bereavement dreams usually include the

mourning. Worden identified four Tasks of Mourning, which

presence of the deceased, there is substantial variability in their

emotional tone and context. Several theorists have made efforts

to identify the archetypal categories of bereavement dreams,

with varying levels of overlap.2,3,8-10 These models diverge

1

Center for Hospice & Palliative Care, Cheektowaga, NY, USA

substantially with regard to dream content, yet all feature

Corresponding Author:

themes of reunion and separation. Among the most frequently Christopher W. Kerr, MD, PhD, Center for Hospice & Palliative Care, 225

cited content themes are the deceased still living and interact- Como Park Boulevard, Cheektowaga, NY 14227, USA.

ing with the dreamer, the dreamer reliving the death of the Email: ckerr@palliativecare.org

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

2 American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine® 00(0)

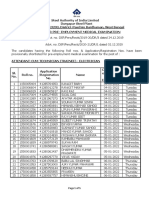

Table 1. Demographic Information of Survey Participants. Methods

Characteristic N ¼ 278 M % SD Participants

Age Participants were selected from a database of primary care-

Participants 63.37 13.77 givers of patients who died between March 2011 and July

Deceased Patients 79.00 12.66 2012 while under the care of a comprehensive hospice pro-

Gender

gram. Sixteen hundred caregivers who had indicated a willing-

Male 75 – 27 –

Female 203 – 73 – ness to be contacted after the death of their loved ones were

Ethnicity randomly selected from this database and mailed a survey

Caucasian 261 – 94.0 – package. The survey response rate was 17.4%; 279 caregivers

African American 9 – 3.2 – returned a response, and 1 response from a minor was removed,

Native American 2 – 0.7 – for a total of 278 participants.

Middle Eastern 2 – 0.7 – The mean age of the respondents was 63.37 years with a

Asian 1 – 0.4 –

range of 23 to 93 years. The mean age of the deceased at the

Multiracial 1 – 0.4 –

Relationship of Deceased to Participant time of death was 79.00 years, with a range of 35 to 101 years.

Spouse 117 – 42.1 – Almost all participants were Caucasian, and most were female.

Mother 99 – 35.6 – The majority of participants had recently lost a spouse or a

Father 26 – 9.4 – mother. Respondents had known their loved ones for an

Grandmother 7 – 2.5 – average of 51.85 years, with a range of 2 to 90 years. Table 1

Sibling 7 – 2.5 – displays more detailed demographic information.

Other 7 – 2.5 –

Friend 6 – 2.2 –

Aunt/Uncle 5 – 1.8 – Materials

Cousin 1 – 0.5 –

A 20-item survey was designed including questions regarding

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. basic demographics, the quality of the respondent’s relation-

ship to the deceased (eg, ‘‘How would you describe your rela-

formulate the process of bereavement in terms of tasks to be tionship with your loved one?’’), dream content and frequency

actively achieved, rather than stages to be passively experi- (eg, ‘‘Following the loss of your loved one, have you experi-

enced. The four tasks are (1) to accept the reality of the loss; enced dreams of him or her?’’), and the impact of dreams on

(2) to process the pain of grief; (3) to adjust to a world in which the bereavement process (eg, ‘‘Do you perceive dreaming of

the deceased is missing; and (4) to emotionally relocate the your loved one to have impacted your emotions in your

deceased and move on with life. He further suggested that the bereavement?’’). All survey questions were closed-ended but

dreams of the bereaved reflect their process of mourning and included spaces for open-ended descriptions of dreams and

that dream content can be correlated with the task of mourning their impact on bereavement.

they are working on at a given time.1 Various researchers have

applied this model to conceptualize bereavement dreams and to Procedures

reinforce the theory that dreams of the bereaved reflect the

mourning process.3,8,11 For example, a person struggling to After potential participants were identified, they were mailed a

process the reality of their loss (task 1) might dream that the letter describing the study and inviting them to participate

deceased is still alive, while a person working to move on with along with the survey and a preaddressed stamped return envel-

their life (task 4) might dream that their loved one appears and ope. The letter accompanying the survey explained that the par-

gives them permission to move on. Worden’s theory1 is consis- ticipants should only return the survey if they consented to

tent with dream content research, which suggests that dreams participate and to allow the use of their de-identified informa-

usually reflect the content and conflict of our waking lives.12 tion in publishable research. Respondents were also invited to

Despite this consonance between grief theory and dream request additional support through our hospice bereavement

research, there is a paucity of quantitative data on the relationship team, if they so wished.

between dreams of the deceased and the process of bereavement.

The present study was designed with the aim of learning from the Results

bereaved themselves, with the following four specific goals: (1)

assess the relative prevalence of dreams of the deceased among Prevalence of Dreams of the Deceased

bereaved family members whose loved ones died while under Dreams of the deceased were common; of 278 respondents,

hospice care; (2) explore the differences between those who 57.9% (n ¼ 161) reported dreaming of their deceased loved

reported dreaming of the deceased and those who did not; (3) ones. Those who dreamed about a loved one did so with vary-

quantify the content of dreams of the recently bereaved; and (4) ing frequency: daily (7.5%, n ¼ 12), weekly (23.6%, n ¼ 38),

assess the perceived impact of the dreams of the bereaved on their monthly (15.5%, n ¼ 25), less than monthly (26.7%, n ¼ 43),

emotional adjustment and cognitions related to their loss. and other (25.5%, n ¼ 41).

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

Wright et al 3

represented visually in Figure 2. Many respondents described

the content of their dreams in vivid detail, and Table 2 lists

examples for each category represented in the data.

Impact of Dreams on Bereavement

Most respondents who dreamed of the deceased felt that this

experience impacted the emotions related to their bereavement

process (60.2%, n ¼ 97). Respondents also assessed the impact

of their dreams on specific bereavement processes (increased,

decreased, no effect).The majority of respondents rated their

dreams as having no effect on 9 of the 12 processes. However,

many also reported an increase in certain emotions and atti-

tudes (eg, acceptance of death, comfort, spirituality, sadness,

quality of life). Figure 3 summarizes the reported impact of

dreams on grief responses of the bereaved.

Some reported that their dreams helped them accept the

death of a loved one. For example, one participant wrote ‘‘[the

dream] put my mind at peace about my brother’s death. I miss

him very much but I know he is in God’s hands and happy.’’

Others described how their dreams helped them to retain a

connection with the deceased: ‘‘I feel closer to mom than at the

Figure 1. Proportions of pleasant and disturbing dreams of the time of her death. At the time I felt cut off. Now feel as if I was

deceased. reconnected in at least a small way.’’ Some explained how their

dreams intensified their feelings of sadness: ‘‘My sister and I

Comparison of Dreamers and Nondreamers cared for our mother around the clock. The dreams just make

me sadder and I miss her when I wake up.’’

Respondents who dreamed of the deceased (mean [M] ¼ 61.21

years of age, standard deviation [SD] ¼ 14.12) were on average

younger than those that did not dream (M ¼ 66.00 years of age, Discussion

SD ¼ 12.76), t(271) ¼ 2.87, P < .01. The loved ones of those that

The current study presents data from a retrospective survey

dreamed (M ¼ 77.19 years of age, SD ¼ 12.85) were also sig-

designed to assess bereavement dreams with respect to preva-

nificantly younger than those loved ones of those that did not

lence, content, and subjective meaning from the perspective of

dream (M ¼ 81.63 years of age, SD ¼ 11.75), t(270) ¼ 2.90,

the bereaved themselves. In the present study, nearly 58% of the

P < .01. Those that dreamed also knew their loved ones (M ¼

bereaved hospice caregivers reported dreaming of the deceased,

50.24 years known, SD ¼ 13.20) for a significantly shorter

which is consistent with other reported prevalence rates that

period of time compared to those that did not dream (M ¼

range between 26% and 90%.5-7 With respect to dream content,

53.92 years known, SD ¼ 15.29), t(262) ¼ 2.09, P < .05. Of

the results of the current study validated aspects of existing mod-

those respondents that did not dream, 52.2% (n ¼ 59) indicated

els of bereavement dreams.2,3,8-10 Commonly reported dream

they would like to dream of their deceased loved ones.

content included dreams in which the deceased was alive, in

health, during illness, in the afterlife, and communicating a mes-

sage to the dreamer. Several previously described dream cate-

Content of Dreams of the Deceased gories were not reported in the current study (eg, deadly

Most respondents reported that their dreams were pleasant (n ¼ invitation or telephone-call dreams4), possibly due to limitations

89), with many also describing both pleasant and disturbing of the survey questions. However, the content of dreams may

dreams (n ¼ 50). A minority experienced only disturbing vary or depend on variables such as length of bereavement,

dreams (n ¼ 11) or dreams not falling into these categories phase of the grief process, nature of the death (eg, violent, peace-

(n ¼ 10). Figure 1 illustrates the relative proportions of partici- ful) as well as the relationship of the dreamer to the deceased.8 A

pants who rated their dreams pleasant or disturbing. definitive categorization of bereavement dream content may

Most respondents who dreamed of the deceased reported therefore prove to be difficult, if not impossible

that their dreams featured pleasant past memories or experi- The current results support the hypothesis that dreams of the

ences (n ¼ 105). Other prominent categories included the bereaved have an inherent therapeutic or healing quality and serve

deceased free of illness (n ¼ 65), memories of the deceased’s to maintain a connection with the deceased during the bereave-

illness or time of death (n ¼ 56), the deceased in the afterlife ment process. The emotional tone of bereavement dreams was

appearing comfortable and at peace (n ¼ 43), and the deceased expressed as pleasant or both pleasant and disturbing, while few

communicating a message (n ¼ 41). Content data are reported purely distressing dreams. The type of bereavement

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

4 American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine® 00(0)

Figure 2. Dreams of the deceased content categories by prevalence.

a

Table 2. Examples of Dream Content Categories.

Dream Content Category Example

Pleasant Memories ‘‘I find the dreams comforting – they are always of pleasant memories. I am sad to wake to reality, but the

memories override the sadness.’’

Deceased Free of Illness ‘‘I occasionally dream of my sister. She is younger with long hair - not the way she looked at her death.’’

Deceased during illness ‘‘In my dreams I see him lying there in the last few minutes of his life’’

Comfortable in the afterlife ‘‘She was in a group of three or four people and just smiled at me. She didn’t say anything, but she looked

healthy and at peace.’’

Communicating a message ‘‘My mother speaks to me while I dream. She tells me things about situations in my life and how to handle

them. I get to hold my mother in my dreams and get to feel her warmth and love.’’

Other ‘‘I dreamed of the deceased, but he didn’t know that he was deceased, and I had to tell him.’’

With other deceased loved ones ‘‘Our daughter Jane had a dream of her [deceased] mother walking on the beach shore holding the hand of a

small boy named Eric. We had previously lost a baby and named him Eric, who had died before Jane was

born. Eric was to be our last of three children, but when he died we had Jane.’’

Unresolved issues ‘‘The fact the times my mother was in my dreams and never spoke made me feel sadder. I just wanted her to

talk to me—maybe try to let me know I didn’t let her down.’’

Distressed in afterlife ‘‘I dreamed that he was very stressed and then became peaceful and went home with God.’’

a

No details were shared for the Memories of End-of-Life Services category.

dream most commonly associated with pleasant content involved the bereavement process. In this study, most respondents noted

reliving pleasant past memories of the deceased. that dreams of the deceased carried emotional significance to

their process of bereavement.

This finding has clear implications for bereavement coun-

Impact on Bereavement and Implications for Counselors seling. As suggested by Worden, dreams of the bereaved hold

Previous studies have not asked the bereaved for their perspec- therapeutic value in assisting to understand the individual’s

tives on the relationship between dreams of the deceased and process of mourning through the identification of mourning

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

Wright et al 5

rates of therapeutic benefit with respect to achieving insight,

understanding, and ability to take actionable steps and were

more likely to have a greater number of positive dreams after

treatment.15 Two small qualitative studies have found prelimi-

nary support for the use of dreams in group counseling with

bereaved parents.16,17 Discussing dreams was found to assist

group participants in processing the emotions related to the loss

of their child. These studies suggest that dreams, especially

troubling ones, may warrant special attention in bereavement

counseling.

Despite the apparent usefulness of working with dreams in

therapy, relatively few therapists are comfortable using them,18

possibly due to misconceptions and negative connotations. For

example, many therapists assume that dream work is inherently

unscientific and inextricably associated with psychoanalysis.12

However, some researchers postulate that dream work is con-

sistent with an empirically based cognitive paradigm. Hess11

developed a new theoretical foundation for using dreams in

counseling with the bereaved by synthesizing the Tasks of

Mourning model with Hill’s Cognitive-Experiential Model of

Dream Interpretation,12 which is based on the principles of cog-

nitive psychology. This empirically supported theory of dream

work suggests that dreams are the consequence of the mind’s

attempts to integrate discrepant waking experiences into preex-

isting cognitive schemata. The 3 stages of dream work under

this model are (1) exploration, in which the therapist assists the

client in identifying the significance of dream symbols through

an associational process, (2) insight, in which the client is

encouraged to link these symbols to waking thoughts, feelings,

and experiences to develop a collaborative interpretation of the

dream, and (3) action, in which the client is encouraged to take

concrete steps based on the interpretation. Hess provides exam-

ples of how all 3 stages in the cognitive–experiential model can

be applied to a dream associated with any of Worden’s four

Tasks of Mourning.11

We did not assess the tasks or stages of mourning, but it is

interesting to examine how dreams reported in our survey can

be accounted for by each task. Some examples follow, using

the framework established by Hess in her application of Hill’s

Figure 3. Impact of dreams of the deceased on bereavement

processes. model. It is important to note that according to this model, no

dream can be interpreted in isolation from the dreamer. Thus,

the following examples are not intended to model the process

tasks, including tasks that represent challenges and hence areas of interpretation.

for therapeutic focus.1 Dreams may facilitate new insights and One participant wrote:

provide a ‘‘safe place’’ in which the dreamer identifies links

between waking events, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors—a I’m searching for mom in my dream but I cannot seem to find

process that mirrors that of psychotherapy.13 her. When I awaken I realize it is a dream.

Although the use of dream work in counseling may be as old

as the field itself, the body of evidence supporting the efficacy This dream may reflect the dreamer’s struggle to accept the

of this therapeutic tool has grown in recent decades.11,14 There reality of their loss (task 1) and their mind’s attempt to integrate

are also limited yet promising reports on the therapeutic value this highly discrepant experience into cognitive schemata. The

of dream work in bereavement therapy specifically. Hill et al repeated jarring experience of awakening to find that the

conducted a study of dream interpretation with 14 participants deceased is, in fact, no longer present can force the dreamer

who had recently lost a loved one and were reporting troubling to slowly accept the finality of what has occurred. A bereave-

dreams. When compared to supportive therapy alone, clients ment counselor’s task in working with someone at this point in

whose therapy focused on troubling dreams reported higher the process might involve using the dreams to promote insight

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

6 American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine® 00(0)

into the reality of the situation and to assist them in processing deceased but rather about reinvesting one’s energy in new

the implications and ramifications of that reality. relationships and life experiences.

Another participant noted:

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

When I awaken from my dreams of mom I find myself crying

uncontrollably. Mom was my life. Losing her has affected me There are several limitations to this study. In spite of the overall

as far as my life seems so empty at times. At times the pain high survey completion rates, many respondents did not com-

is unbearable. plete the section indicating the impact of their dreams on grief

responses (34%-39% of participants left various parts of this

Here, it seems that the dreamer has accepted the fact that section blank). It is possible that these respondents did not feel

her mother is not returning and is experiencing the incredible that they could identify the impact of their dreams with that

pain associated with grief (task 2). For a counselor presented degree of specificity. In fact, most who did complete this sec-

with this client, dreams may serve as means for facilitating tion reported that their dreams had ‘‘no effect’’ on the specific

expression of feelings, exploring the sources and meaning emotions related to bereavement. This reflects a stark contrast

of pain, and facilitating a discussion of coping skills to the 60% who indicated a general impact of their dreams on

development. their bereavement. A second limitation was that the current sur-

A third participant described her dreams of her mother: vey instrument did not include all dream content categories as

suggested by other researchers. This limited our ability to

I have had dreams of my mother on special occasions (eg, assess the relative validity of these models. A third limitation

mother’s day, birthday, etc) and her indirectly relaying a was that date of death information was not included in the

message to me and helping me in life generally. survey, preventing analyses between elapsed time, content, and

impact on bereavement. Furthermore, cross-cultural analysis

This series of dreams may reflect the dreamer’s process of was prevented by the sample’s cultural homogeneity.

adjustment to life without her mother (task 3), which includes Future research could solicit more open-ended information

the realization that her mother is no longer around to give regarding the impact of bereavement dreams on the process

advice or to assist her. This represents what Worden termed of mourning over time by inquiring about elapsed time since

an external adjustment, involving a change in one’s functioning death, expanding dream categories, and assessing the respon-

in the world. He also identified internal and spiritual adjust- dents’ current tasks of mourning as described by Worden.1

ments, relating to one’s sense of self and assumptive world- Because this study was retrospective, its results are subject to

view, respectively.1 A counselor working with this client recall bias on the part of participants who may only have

might make use of dreams in exploring the ways these changes remembered or reported their most striking and memorable

are reflected through dream symbolism. One possible insight dreams. Future research could utilize dream diaries to facilitate

gained from these ‘‘advice’’ dreams in particular might be the dream recall and a prospective design to capture dreams as they

realization that the dreamer possesses the necessary strength occur. Further research may also be warranted to determine the

and wisdom to manage her life with in herself, as evidenced efficacy of bereavement therapy that includes dream work

by the helpful nature of these dream messages. based on the approach described by Hill12,19 and Hess.11

A fourth participant wrote:

Conclusions

I dreamed that my husband was there and I asked him to come

back, but he wouldn’t come back. He told me he was leaving This study achieved its four goals. First, the relative prevalence

me for someone else. I had this dream several times. Then, after of dreams of the deceased was found to be high among recently

I began dating someone I had the same dream, but at the end he bereaved hospice caregivers, congruent with earlier studies.

said he would come back, and I told him I didn’t want him back. Second, we found some small differences in age and length

He got into his truck and left. of relationship between those who dreamed of the deceased and

those who did not, suggesting that these variables might have a

This dream may reflect the entire process of working on the relationship to dreaming. Third, this study quantified major

tasks of grief beginning with the dreamer’s repeated attempts to dream content categories, providing validation for earlier mod-

bring her husband back into her life. The changed ending in the els. Finally, and most importantly, this study demonstrates that

final dream seems to reflect that the deceased’s role in the drea- many bereaved persons consider their dreams to be important

mer’s life has changed, and that she is moving on with her life features of their bereavement. This suggests that dreams

(task 4). The dreamer’s decision to date someone new is deserve increased clinical attention from counselors who work

reflected in her attitudinal shift in the dream. It is possible that with this population, in spite of the widespread reluctance of

such a dream may raise feelings of guilt in the dreamer, and one counselors in general to address dreams. Empirically validated

task for a grief counselor would be to assist her in understand- approaches to dream work such as the Cognitive–Experiential

ing the ways her relationship to the deceased has changed. As Model may prove a useful tool for bereavement counselors.

Worden suggests, this task is not about ‘‘forgetting’’ the Although working with dreams is clearly not a panacea for the

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

Wright et al 7

pain experienced by the recently bereaved, the present study 8. Garfield P. Dreams in bereavement. In: Barrett D, ed. Trauma and

provides initial justification for further inquiry into this dreams. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996:

approach. 186-211.

9. LoConto DG. Death and dreams: A sociological approach to

Acknowledgments grieving and identity. Omega: J Death Dying. 1998;37(3):

We would like to thank William D. Riemer for his technical assistance 171-185.

with developing a database for the study. 10. Belicki K, Gulko N, Ruzycki K, Aristotle J. Sixteen years of

dreams following spousal bereavement. Omega: J Death Dying.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests 2002;47(2):93-106.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to 11. Hess SA. Dreams of the bereaved. In: Hill CE, ed. Dream work in

the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. therapy: Facilitating exploration, insight, and action. Washing-

ton, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:169-185.

Funding 12. Hill CE. Working With Dreams in Psychotherapy. New York,

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

and/or publication of this article. 13. Hartmann E. Making connections in a safe place: Is dreaming

psychotherapy? Dreaming. 1995;5(4):213-228.

References 14. Pesant N, Zadra A. Working with dreams in therapy: what do we

1. Worden JW. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A handbook know and what should we do? Clinical psychology review. 2004;

for the mental health practitioner. 3rd ed. New York, NY: 24(5):489-512.

Springer Publishing Co; 2002. 15. Hill CE, Zack JS, Wonnell TL, et al. Structured brief therapy with

2. Barrett D. Through a glass darkly: Images of the dead in dreams. a focus on dreams or loss for clients with troubling dreams and

Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 1991;24(2):97-108. recent loss. J Couns Psychol. 2000;47(1):90-101.

3. Cookson K. Dreams and death: An exploration of the literature. 16. Begovac B, Begovac I. Dreams of deceased children and counter-

Omega: J Death Dying. 1990;21(4):259-281. transference in the group psychotherapy of bereaved mothers:

4. Garfield PL. The Dream Messenger: How Dreams of the Departed Clinical illustration. Death Stud. 2012;36(8):723-741.

Bring Healing Gifts. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1997. 17. Moss E. Working with dreams in a bereavement therapy group.

5. Kalish RA, Reynolds DK. Phenomenological reality and post- Int J Group Psychoth. 2002;52(2):151-170.

death contact. J Sci Study Relig. 1973;12(2):209-221. 18. Crook RE, Hill CE. Working with dreams in psychotherapy: The

6. Gerber I. Perspectives on Bereavement. New York: Arno Press; therapists’ perspective. Dreaming. 2003;13(2):83-93.

1979. 19. Hill CE. Dream Work in Therapy: Facilitating Exploration,

7. Klugman CM. Dead men talking: evidence of post death contact and Insight, and Action. Washington, DC: American Psychological

continuing bonds. Omega: J Death Dying. 2006;53(3):249-262. Association; 2004.

Downloaded from ajh.sagepub.com at University at Buffalo Libraries on March 1, 2013

View publication stats

You might also like

- End of Life DeamsDocument10 pagesEnd of Life DeamsMariangela GiulianeNo ratings yet

- The Hormesis Effect: The Miraculous Healing Power of Radioactive StonesFrom EverandThe Hormesis Effect: The Miraculous Healing Power of Radioactive StonesNo ratings yet

- Medicine American Journal of Hospice and PalliativeDocument9 pagesMedicine American Journal of Hospice and PalliativeLLloydNo ratings yet

- Sacred Dreams & Life Limiting Illness: A Depth Psychospiritual ApproachFrom EverandSacred Dreams & Life Limiting Illness: A Depth Psychospiritual ApproachNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Experiences of Transcendence of Patients With Advanced CancerDocument12 pagesSpiritual Experiences of Transcendence of Patients With Advanced CancertalleresclarabaffaNo ratings yet

- Dying Is A Transition 2012Document9 pagesDying Is A Transition 2012talleresclarabaffaNo ratings yet

- AM J HOSP PALLIAT CARE-2015-Coelho-1049909114565660Document8 pagesAM J HOSP PALLIAT CARE-2015-Coelho-1049909114565660Mayra Armani DelaliberaNo ratings yet

- Neuropalliative Care: A Guide to Improving the Lives of Patients and Families Affected by Neurologic DiseaseFrom EverandNeuropalliative Care: A Guide to Improving the Lives of Patients and Families Affected by Neurologic DiseaseClaire J. CreutzfeldtNo ratings yet

- Articol 1 ADocument12 pagesArticol 1 AClara Iulia BoncuNo ratings yet

- Mourning Protocol Details and The Cognitive Behavior Therapy Applicability AuthorsDocument13 pagesMourning Protocol Details and The Cognitive Behavior Therapy Applicability AuthorsGraziele ZwielewskiNo ratings yet

- Humanizing Addiction Practice: Blending Science and Personal TransformationFrom EverandHumanizing Addiction Practice: Blending Science and Personal TransformationNo ratings yet

- The Abrasive PatientDocument149 pagesThe Abrasive Patientmaruan_trascu5661No ratings yet

- Grief Following Miscarriage A Comprehensive Review of The LiteratureDocument14 pagesGrief Following Miscarriage A Comprehensive Review of The LiteratureAdiwisnuuNo ratings yet

- HEALING YOURSELF UNDERSTANDING HOW YOUR MIND CAN HEAL YOUR BODYFrom EverandHEALING YOURSELF UNDERSTANDING HOW YOUR MIND CAN HEAL YOUR BODYNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography On The Concept of GriefDocument4 pagesAnnotated Bibliography On The Concept of GriefKeyvoh KeymanNo ratings yet

- Dreams and Guided Imagery: Gifts for Transforming Illness and CrisisFrom EverandDreams and Guided Imagery: Gifts for Transforming Illness and CrisisNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review of Western Bereavement TheoryDocument6 pagesA Literature Review of Western Bereavement TheoryafmzndvyddcoioNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Five Stages of Grief - Class 6 DocumentDocument2 pagesBeyond The Five Stages of Grief - Class 6 DocumentoksanaNo ratings yet

- Journeys with the Black Dog: Inspirational Stories of Bringing Depression to HeelFrom EverandJourneys with the Black Dog: Inspirational Stories of Bringing Depression to HeelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Consciousness and Healing: The Dark Side of Consciousness and The Therapeutic RelationshipDocument12 pagesConsciousness and Healing: The Dark Side of Consciousness and The Therapeutic RelationshipluciantimofteNo ratings yet

- Messages from an Illness: Deepening Faith Through CancerFrom EverandMessages from an Illness: Deepening Faith Through CancerNo ratings yet

- Compare and ContrastDocument4 pagesCompare and ContrastKathy LeNo ratings yet

- My Imaginary Illness: A Journey into Uncertainty and Prejudice in Medical DiagnosisFrom EverandMy Imaginary Illness: A Journey into Uncertainty and Prejudice in Medical DiagnosisNo ratings yet

- Supporting Patients Who Are BereavedDocument5 pagesSupporting Patients Who Are BereavedVictoria AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Blume - When Therapists CryDocument245 pagesBlume - When Therapists CryPixie Willo100% (2)

- The Integrated Self: A Holistic Approach to Spirituality and Mental Health PracticeFrom EverandThe Integrated Self: A Holistic Approach to Spirituality and Mental Health PracticeNo ratings yet

- Euthanasie Dissertation PhilosophieDocument5 pagesEuthanasie Dissertation PhilosophieWhereCanIFindSomeoneToWriteMyCollegePaperUK100% (1)

- Empowered Healing: Creating Quality of Life While Journeying With CancerFrom EverandEmpowered Healing: Creating Quality of Life While Journeying With CancerNo ratings yet

- Humor and OncologyDocument4 pagesHumor and OncologyNaomiFetty100% (1)

- The Delirium Symptom Interview An Interview For The Detection of Delirium Symptoms in HospitalizedPatientsDocument10 pagesThe Delirium Symptom Interview An Interview For The Detection of Delirium Symptoms in HospitalizedPatientsPiramaxNo ratings yet

- At the Time of Death: Symbols & Rituals for Caregivers & ChaplainsFrom EverandAt the Time of Death: Symbols & Rituals for Caregivers & ChaplainsNo ratings yet

- End of Life SwallowingDocument5 pagesEnd of Life SwallowingCamila Jaque RamosNo ratings yet

- Soul Service: A Hospice Guide to the Emotional and Spiritual Care for the DyingFrom EverandSoul Service: A Hospice Guide to the Emotional and Spiritual Care for the DyingNo ratings yet

- Unimaginable Storms A Search For Meaning in Psychosis by Steiner, John Williams, Paul Jackson, MurrayDocument256 pagesUnimaginable Storms A Search For Meaning in Psychosis by Steiner, John Williams, Paul Jackson, MurraySeán GallagherNo ratings yet

- Welcome to the Other Side!: Reclaiming Life After Surviving and Caregiving Through the Abyss of CancerFrom EverandWelcome to the Other Side!: Reclaiming Life After Surviving and Caregiving Through the Abyss of CancerNo ratings yet

- Potential Use of Ayahuasca in Grief TherapyDocument26 pagesPotential Use of Ayahuasca in Grief TherapyRafa ArzolaNo ratings yet

- Death Anxiety Od Brain Tumor PatientsDocument10 pagesDeath Anxiety Od Brain Tumor Patientsluxlelito97No ratings yet

- The Grief and Bereavement Experiences of Informal Caregivers: A Scoping Review of The North American LiteratureDocument17 pagesThe Grief and Bereavement Experiences of Informal Caregivers: A Scoping Review of The North American LiteratureSorina ElenaNo ratings yet

- Treating Adult Survivors of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Neglect PDFDocument328 pagesTreating Adult Survivors of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Neglect PDFNegura Giulia100% (19)

- Complicated Grief Therapy For Clinicians: An Evidence Based Protocol For Mental Health PracticeDocument9 pagesComplicated Grief Therapy For Clinicians: An Evidence Based Protocol For Mental Health Practice110780No ratings yet

- Cancer As A MetaphorDocument10 pagesCancer As A MetaphorVanessa SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Human Encounter With DeathDocument126 pagesThe Human Encounter With DeathSujan AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Bereavement in Adult LifeDocument9 pagesBereavement in Adult LifeAzhar MastermindNo ratings yet

- Taranslate PaliatifDocument5 pagesTaranslate PaliatiffitriNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Case StudyDocument10 pagesSchizophrenia Case StudyAnanya GulatiNo ratings yet

- Kubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf (Done)Document6 pagesKubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf (Done)Plugaru CarolinaNo ratings yet

- Psychology of Emotions, Motivations and Actions Psychology (0) - Libgen - LC 2Document141 pagesPsychology of Emotions, Motivations and Actions Psychology (0) - Libgen - LC 2ျပည္ စိုးNo ratings yet

- On Death and DyingDocument35 pagesOn Death and DyingShalini MittalNo ratings yet

- Nedostatak Uvida Kod Oboljelih Od Shizofrenije: Definicija, Etiološki Koncepti I Terapijske ImplikacijeDocument7 pagesNedostatak Uvida Kod Oboljelih Od Shizofrenije: Definicija, Etiološki Koncepti I Terapijske ImplikacijeZoran SvetozarevićNo ratings yet

- Paul J. Moon, PHD 2016Document4 pagesPaul J. Moon, PHD 2016Vania CasaresNo ratings yet

- Taranslate PaliatifDocument5 pagesTaranslate PaliatiffitriNo ratings yet

- Death Dying and BereavementDocument5 pagesDeath Dying and BereavementImmatureBastardNo ratings yet

- The Iconography of Mourning and Its Neural Correlates: A Functional Neuroimaging StudyDocument11 pagesThe Iconography of Mourning and Its Neural Correlates: A Functional Neuroimaging Studyareesha naseerNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Loss: Mental Health Consequences and Implications For Treatment and PreventionDocument7 pagesTraumatic Loss: Mental Health Consequences and Implications For Treatment and Preventionareesha naseerNo ratings yet

- Complicated Grief and Post-Traumatic Growth in Traumatically Bereaved Siblings and Close FriendsDocument15 pagesComplicated Grief and Post-Traumatic Growth in Traumatically Bereaved Siblings and Close Friendsareesha naseerNo ratings yet

- John Bowlby TheoryDocument11 pagesJohn Bowlby Theoryareesha naseerNo ratings yet

- Positive Psy ArticleDocument10 pagesPositive Psy Articleareesha naseerNo ratings yet

- Psychophysiological Disorders: Bs 6A+B Urwah AliDocument29 pagesPsychophysiological Disorders: Bs 6A+B Urwah Aliareesha naseerNo ratings yet

- Current Status of Food Processing IndustryDocument19 pagesCurrent Status of Food Processing IndustryAmit Kumar90% (21)

- B1+ UNIT 1 Life Skills Video Teacher's NotesDocument1 pageB1+ UNIT 1 Life Skills Video Teacher's NotesXime OlariagaNo ratings yet

- MODULE 8: Settings, Processes, Methods, and Tools in Social WorkDocument4 pagesMODULE 8: Settings, Processes, Methods, and Tools in Social WorkAlexandra Nicole RugaNo ratings yet

- Water Is The Basic Necessity For The Functioning of All Life Forms That Exist On EarthDocument2 pagesWater Is The Basic Necessity For The Functioning of All Life Forms That Exist On EarthJust TineNo ratings yet

- Hortatory ExpositionDocument2 pagesHortatory ExpositionfazaNo ratings yet

- Legaspi, Ariel Rafael S. BS Nursing 2BDocument2 pagesLegaspi, Ariel Rafael S. BS Nursing 2BJohn MalonesNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - The Nature of Work EthicsDocument10 pagesModule 3 - The Nature of Work EthicsMaria Jasmin LoyolaNo ratings yet

- Group 8 Written OutputDocument11 pagesGroup 8 Written OutputCIARA JOI N ORPILLANo ratings yet

- 68-Article Text-261-1-10-20191204Document9 pages68-Article Text-261-1-10-20191204Andi Dwi Resti JuliastutiNo ratings yet

- Barangay Devepment PlanDocument21 pagesBarangay Devepment Planjeoffryabonitalla311No ratings yet

- Chi Bu Zo PreliminaryDocument8 pagesChi Bu Zo PreliminaryChinwuba Samuel EbukaNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mapeh 4 - Q3 - W3Document10 pagesDLL - Mapeh 4 - Q3 - W3Dianne Grace IncognitoNo ratings yet

- Exams UNAM PDFDocument105 pagesExams UNAM PDFHugoHdezNo ratings yet

- CHN1 Worksheet1Document5 pagesCHN1 Worksheet1Chariza MayNo ratings yet

- Solutions of Eco Therapy: General MetricsDocument3 pagesSolutions of Eco Therapy: General MetricsHaseem AjazNo ratings yet

- PB - 20-26 (F MEngoub) PDFDocument9 pagesPB - 20-26 (F MEngoub) PDFMarie Cris Gajete MadridNo ratings yet

- Lisid Tapongot ArticleDocument3 pagesLisid Tapongot Articlerandz c thinksNo ratings yet

- Plumbing Design and Estimate (Second Edition)Document175 pagesPlumbing Design and Estimate (Second Edition)Kellybert Fernandez100% (1)

- 12 Steps To Positive Team Conflict Resolution: Learning GuideDocument5 pages12 Steps To Positive Team Conflict Resolution: Learning GuideMin MinNo ratings yet

- Notice For PEMEDocument5 pagesNotice For PEMESwarnava LahaNo ratings yet

- Endometriosis The Pathophysiology As An Estrogen-Dependent DiseaseDocument7 pagesEndometriosis The Pathophysiology As An Estrogen-Dependent DiseaseHarrison BungasaluNo ratings yet

- CW2500 Part A - ISS 26052015Document10 pagesCW2500 Part A - ISS 26052015mitramgopalNo ratings yet

- 0811 Employee Involvement PDFDocument2 pages0811 Employee Involvement PDFFirman Suryadi RahmanNo ratings yet

- Adviser Action PlanDocument3 pagesAdviser Action PlanJezelle ManaloNo ratings yet

- Obat Tahap 3Document7 pagesObat Tahap 3kulanavhieaNo ratings yet

- The Velvet Rage - Overcoming The Pain of Growing Up Gay in A Straight Man's World - PDF RoomDocument248 pagesThe Velvet Rage - Overcoming The Pain of Growing Up Gay in A Straight Man's World - PDF RoomJasson Cerrato100% (3)

- Tooth Positions On Complete Dentures : David M. WattDocument14 pagesTooth Positions On Complete Dentures : David M. WattArun PrasadNo ratings yet

- The Wisdom To Know The Difference - ACT Manual For Substance UseDocument148 pagesThe Wisdom To Know The Difference - ACT Manual For Substance UseLaura Bauman100% (1)

- Assessment of The Urinary System: Chelsye Marviyouna Dearianto 1814201018Document19 pagesAssessment of The Urinary System: Chelsye Marviyouna Dearianto 1814201018Sinta WuLandariNo ratings yet

- Las 2.3 in Hope 4Document4 pagesLas 2.3 in Hope 4Benz Michael FameronNo ratings yet