Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Personal View: Anita Thapar, Miriam Cooper, Michael Rutter Frcpsych

Personal View: Anita Thapar, Miriam Cooper, Michael Rutter Frcpsych

Uploaded by

Raul Morales VillegasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Personal View: Anita Thapar, Miriam Cooper, Michael Rutter Frcpsych

Personal View: Anita Thapar, Miriam Cooper, Michael Rutter Frcpsych

Uploaded by

Raul Morales VillegasCopyright:

Available Formats

Personal View

Neurodevelopmental disorders

Anita Thapar, Miriam Cooper, Michael Rutter FRCPsych

Neurodevelopmental disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder, Lancet Psychiatry 2016

although most commonly considered in childhood, can be lifelong conditions. In this Personal View that is shaped by Published Online

clinical experience and research, we adopt a conceptual approach. First, we discuss what disorders are December 12, 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

neurodevelopmental and why such a grouping is useful. We conclude that both distinction and grouping are helpful

S2215-0366(16)30376-5

and that it is important to take into account the strong overlap across neurodevelopmental disorders. Then we

Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

highlight some challenges in bridging research and clinical practice. We discuss the complexity of clinical phenotypes Section, Division of

and the importance of the social context. We also argue the importance of viewing neurodevelopmental disorders as Psychological Medicine and

traits but highlight that this is not the only approach to use. Finally, we consider developmental change across the Clinical Neurosciences;

MRC Centre for

life-span. Overall, we argue strongly for a flexible approach in clinical practice that takes into consideration the high

Neuropsychiatric Genetics and

level of heterogeneity and overlap in neurodevelopmental disorders and for research to link more closely to what is Genomics, Cardiff University

observed in real-life practice. School of Medicine, Cathays,

Cardiff, UK

(Prof A Thapar FRCPsych,

Introduction schizophrenia after puberty. These disorders are also

M Cooper MRCPsych); and MRC

Neurodevelopmental disorders are complex conditions characterised by prominent early onset neurocognitive SGDP Centre, Institute of

that are not straightforward to conceptualise. In this deficits and they more commonly affect male individuals.5 Psychiatry, Psychology and

Personal View, we discuss some key issues for clinicians Although highly heritable,6 neurodevelopmental disorders Neuroscience, King’s College,

London, UK

and scientists to consider. Our views have been shaped are typically multi-factorial in origin; single major causes

(Prof M Rutter FRCPsych)

by clinical practice and research, and the intention of this are rare (eg, fetal alcohol syndrome, genetic syndromes)

Correspondence to:

article is to offer our perspective on neurodevelopmental and such forms of disorder are classified elsewhere.2 Prof Anita Thapar, Child

disorders. Finally, the level of overlap between these disorders & Adolescent Psychiatry Section,

The term neurodevelopmental has been applied to a very and their constituent symptom dimensions is high. Division of Psychological

Medicine and Clinical

broad group of disabilities involving some form of This further supports the rationale for considering Neurosciences; MRC Centre for

disruption to brain development. This definition groups them together. As is true of all classification systems Neuropsychiatric Genetics and

together a very wide range of neurological and psychiatric and diagnostic groupings, neurodevelopmental disorders Genomics, Cardiff University

problems that are clinically and causally disparate; for are highly heterogeneous in terms of their clinical School of Medicine, Hadyn Ellis

Building, Maindy Road, Cathays,

example, rare genetic syndromes, cerebral palsy, congenital characteristics, causes, treatment responses, and outcomes; Cardiff CF24 4HQ, UK

neural anomalies, schizophrenia, autism, attention deficit there is no specific clinical or biological characteristic that thapar@cardiff.ac.uk

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and epilepsy. In our view,

although it is important to recognise the importance of

early and lifelong developmental processes for health Key research questions

problems, an overly broad approach to grouping • Using longitudinal patient and population-based cohort

neurodevelopmental disorders becomes unhelpful.1,2 designs, what potentially modifiable factors optimise

In this Personal View, we adopt the approach of DSM-53 neurodevelopmental outcomes? Test causal effects

that groups ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual through different research approaches

disability, communication disorders, specific learning (eg, quasi-experimental and animal studies).

disorders, and motor disorders (eg, developmental • How does multi-morbidity affect neurodevelopmental

coordination disorder and tic disorders) as neuro- outcomes and the threshold for treatment

developmental disorders. Although we are not enthusiastic (eg, longitudinal observational studies, treatment trials of

about all aspects of DSM-5, as discussed previously,4 this complex disorders)?

approach to grouping neurodevelopmental disorders is a • What is the natural history of neurodevelopmental

useful one for various reasons.2 disorders in the general population across ages (eg, via

longitudinal population cohort designs)?

Why group neurodevelopmental disorders? • How does social context (within and across countries)

One of the key defining characteristics of these neuro- contribute to neurodevelopmental disorder associated

developmental disorders is that they typically onset in impairments? For example, do longer-term outcomes

childhood, before puberty. They are also distinguished (eg, employment, criminal behaviour) and impairments

from many neuropsychiatric disorders by their clinical differ across time and populations? This could be achieved

course: despite being subject to maturational changes, by investigating outcomes in low-income and

neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD, autism middle-income countries versus high-income countries.

spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and learning • Can we identify neurodevelopmental disorder subtypes

and communication disorders tend to show a steady course that are clinically useful and that might transcend

rather than the remitting and relapsing pattern diagnostic boundaries and predict functional outcomes?

that commonly characterises mood disorders and

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5 1

Personal View

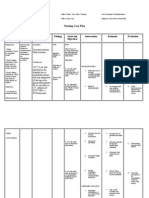

Domains of difficulties that could

can help ensure assessment and intervention across all

Examples of agencies that might

affect children with neuro- be involved in addressing these neurodevelopmental domains and explicitly recognise the

developmental disorders difficulties during assessment, overlaps. The same argument could apply to research that

treatment, and follow-up

typically focuses on single diagnostic problems.

Emotional Mental health

Behavioural Mental health, social care, voluntary Why it is important to retain diagnostic

Social / family adversity and stress sector

Social care, voluntary sector, primary distinctions

care Although grouping of neurodevelopmental disorders is

Scholastic / learning Educational sector useful, it remains necessary to recognise important

Communication Speech and language therapy

Motor Physiotherapy, occupational therapy

distinctions between the different subtypes. For example,

Physical health Paediatrics, physiotherapy, the different effects of medication show that despite

occupational therapy overlaps, neurodevelopmental disorders are not biologically

or clinically identical sets of problems. Although stimulant

Co isord

ID

medication9 and atomoxetine10 alleviate symptoms of

m er

d

m s

un

ADHD and atypical antipsychotics can reduce severe tics,11

ica

tio

none of these medications affect core features of the

n

ASD ADHD other neurodevelopmental disorders. Distinct diagnostic

categories also provide a means for clinicians to readily

communicate patients’ difficulties with each other and with

M isord

rd g

ot e

so in

d

s

di arn

or rs

er

the patients themselves. Thus, there is a clear rationale to

Le

retain the practice of distinguishing these disorders as well

as grouping them.

Figure 1: Assessment and management of neurodevelopmental

problems—the potential for fragmentation of services

ID=intellectual disability. ASD=autism spectrum disorder. ADHD=attention Are neurodevelopmental disorders more than

deficit hyperactivity disorder. their defining symptoms?

Tradition has influenced the defining features of many

clearly distinguishes this grouping from other neuro- neurodevelopmental disorders and some of the decisions

psychiatric disorders. For example, tic disorders do not for inclusion might be considered arbitrary. Phenotypically,

tend to show a steady course and ADHD can remit in neurodevelopmental disorders are more than a defining

some. Schizophrenia and early onset conduct disorder are set of symptoms and extend beyond the boundaries of

commonly characterised by early cognitive and develop- a neurodevelopmental group. Indeed, Kanner, in his

mental impairments but are grouped separately in DSM-5, 1969 article on differential diagnosis,12 highlighted the

which has been discussed elsewhere.2 tendency to pigeonhole patients into a category rather

Nevertheless, the early age of onset and high level of than really understand them—“that children had not read

overlap means that grouping neurodevelopmental the right books” when it came to diagnosis. If we take

disorders in this way is also clinically useful. Assessment ADHD as an example, relevant, common ADHD profiles

and treatment for children with these disorders requires (figure 2) include not only its defining symptoms

specialists from a range of disciplines (eg, child (hyperactive-impulsiveness, inattention) and features of

psychiatrist, psychologist, paediatrician, speech and other neurodevelopmental disorders but also additional

language therapist, and occupational therapist) and cognitive deficits such as impaired working memory and

agencies (eg, health care and education), and treatment planning.13,14 Equally, emotional features including mood

can be fragmented (figure 1). To provide one example, in lability and irritability used to be considered an integral

the UK a child typically requires assessment for ADHD in aspect of ADHD15 but would now be considered as part of

a child mental health or paediatric service; co-occurring a co-occurring disorder (eg, anxiety, depression, or

reading disability is the domain of education services, oppositional defiant disorder). The overlap of ADHD with

motor coordination problems need to be assessed by conduct problems is also prominent.16 Some of these

an occupational therapist, and language or social symptom profiles will be recognised as an additional

communication difficulties are the specialist domain of diagnosis. However, if symptoms do not achieve the

speech and language therapists. Many of these threshold for a diagnosis, they will not be captured for the

professionals are based in different services and local purpose of either research or clinical practice, yet will be

assessment and treatment provision are often organised an important source of heterogeneity; the clinical

around a single diagnosis (eg, ADHD7 or autism spectrum implications of sub-threshold symptoms will be discussed

disorder8) in a number of countries. If co-occurrence of later in this Personal View.

neurodevelopmental disorders is the rule rather than the The same tradition has influenced diagnostic exclusion

exception in clinical practice,2 then grouping professional criteria. For example, it has long been appreciated that the

expertise, services and resources for children with these autistic spectrum includes children with intellectual

problems as part of a neurodevelopmental hub of expertise disability, but in the case of ADHD, the absence of

2 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5

Personal View

intellectual disability was highlighted as important.17 psychosocial adversity. In a UK population-based study,25

However, this assumption is now recognised to be invalid, the total childhood burden of neurodevelopmental

and the practice of failing to diagnose ADHD in the and conduct problems predicted a persistent ADHD

presence of intellectual disabilityis starting to change.18,19 symptom trajectory to adolescence.

The finding that those exposed to early, severe privation Other evidence indicates that different symptom profiles

display features of so-called quasi-autism20 shows how show specificity in relation to the type of later

disorders can present in an unusual fashion in an psychopathology and functional outcome.26,27 For example,

atypical social context. This highlights the importance of in a Swedish study of multiple neurodevelopmental

why assessments of phenomenology need to extend problems,28 childhood ADHD predicted adolescent

beyond core diagnostic criteria—and the constraints of a antisocial behaviour and impaired functioning inde-

structured interview—and why assessing social risk pendent of other neurodevelopmental problems.

matters. However, in clinical settings, assessments will A systematic review29 of longitudinal autism spectrum

typically extend beyond diagnostic items and most disorder studies has highlighted that child intellectual

clinicians would accept the importance of assessing ability (measured by IQ) and early language ability appear

social context and taking into account an individual’s to be the strongest predictors of outcome. The degree to

current resources (eg, cognitive ability, quality which later functional and psychiatric outcomes of

of parenting, income) and demands (eg, classroom neurodevelopmental disorders are predicted by specific

environment), and their level of functioning to devise a symptom profiles or the total burden of problems needs

comprehensive management plan. further investigation, as do the biological and social

Gaps between research and clinical practice need to be mechanisms that explain variation in outcomes.

bridged. Our view is that observation and clinical insights Longitudinal studies that span from childhood to

remain valuable for informing research questions. Also, adulthood are required to address such questions.

research participants need to be characterised beyond

a single core diagnosis; for example by assessing participants Multi-morbidity in clinical practice

across dimensions of symptoms, functioning, and social The concept of multi-morbidity acknowledges the clinical For more on Multi-morbidity

factors beyond the primary diagnosis. A shared measurement importance of multiple problems in a single individual. see https://www.nice.org.uk/

guidance/indevelopment/gid-

toolkit used by different health-care professionals and Multi-morbidity is commonly defined as the presence of cgwave0704

researchers might be helpful in this context. two or more chronic conditions in the same individual

and is now a major concern in general medicine and

Why are profiles beyond core diagnostic features primary care because of growing recognition that multi-

relevant? morbidity is common and has important clinical and

First, for clinicians, different problem areas could require service implications.30

different evidence-based treatments that would not be Fragmented service provision is one problem for

captured by treatment guidelines for a single neuro- patients with multi-morbidity. Clinical pathways that

developmental disorder; for example cognitive behavioural focus explicitly on the diagnostic process of one condition

strategies for anxiety21 and parenting interventions for alone could be missing salient features of other disorders.

behaviour problems.22 Secondly, an individual’s symptom Another is that assessment and treatment guidelines,

profile across multiple dimensions can provide a useful including those relevant for ADHD and autism spectrum

prognostic index. Co-occurrence rates of problems and disorder,7,8 typically focus on a single disorder, yet

disorders are higher in clinics—so called Berkson’s bias— treatment needs and prognosis might be altered in the

which is unsurprising given that those with problems in presence of other disorders.

multiple disorder domains are more severely impaired

than those with problems in fewer domains.23 Neurodevelopmental problems Cognitive impairments

In addition to the selection of appropriate treatments, eg, social communication, language, eg, executive function, response

motor difficulties inhibition

the outcomes must be considered. What sorts of

co-occurring problems are associated with a poorer

outcome? One possibility is that it is the consequence of Core ADHD symptoms that contribute

to primary diagnosis

the total burden of childhood problems regardless of the Hyperactivity

nature of psychopathology. Copeland and colleagues24 Impulsiveness

Inattention

addressed this using the Great Smoky Mountains

longitudinal study. These investigators found that the

cumulative childhood burden of psychopathology was Emotional Behavioural

eg, emotional lability, irritability, anxiety eg, aggression, headstrong/hurtful

the best predictor of adult health (eg, addictions, links with later depression links with later antisocial behaviour

suicidality, serious physical illness), legal outcomes

(eg, criminal act), financial problems (eg, unable to keep Figure 2: Common clinical profiles associated with ADHD: where disaggregating a single diagnosis can be helpful

a job), and social outcomes (eg, no social support), even The necessity of simultaneous interventions for the total profile of difficulties that accompany the primary diagnosis,

allowing for adult psychopathology and childhood even if these do not reach the required threshold for a so-called comorbid diagnosis, needs scientific assessment.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5 3

Personal View

How might treatment be affected? First, the threshold Where does the cutoff point on a dimension lie?

for treating one condition might be altered by the This question is not straightforward to address because it

presence of other conditions (eg, in the presence of depends on what the cutoff point is required for.

certain conditions including renal disease and diabetes, In general for child psychopathology, sub-threshold

the threshold for treating hypertension is lower).31 diagnoses (insufficient symptoms to make a diagnosis

Second, the effectiveness of a recommended treatment but some evidence of impairment) are common, and are

for the primary condition might be moderated by the clinically important in terms of predicting poorer adult

presence of other conditions. This has not been widely mental health and functional outcomes.24 However,

investigated for child psychopathology although there expanding diagnoses is unhelpful because there are

are some exceptions.21,32 For example, in the case potential social, psychological, and health risks,44 as well

of ADHD, behavioural interventions appear to be as benefits of applying a diagnostic label and providing

especially helpful for those with anxiety,32 and although treatments. For example, NICE guidance for ADHD7

stimulants reduce ADHD symptoms in those with applies a lower threshold for psychosocial intervention

intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder, than for medication and recommends a step-wise

medication is less well-tolerated in these groups of treatment approach,14 but that does not deal with the

patients.18,33 At present, we have limited evidence on public health issue of sub-threshold cases of any

how clinical management might be altered in neurodevelopmental disorder.

the context of neurodevelopmental multi-morbidity;

for example, should the threshold for providing What is the dimension?

intervention for communication impairments or autism Another question is, how should one define the

spectrum disorder be lowered in the presence of underlying dimension given that a diagnosis is more

ADHD? Typically, the diagnostic process is hierarchical than just one trait? For example, ADHD symptom scores

and parsimonious and sometimes that is helpful are highly correlated with many other traits, so a diagnosis

because it simplifies the key issues and can help focus of ADHD might not even be best conceptualised as lying

on the predominant features. However, it is being at the extreme of a single measured ADHD trait (ie, total

increasingly recognised that the use of a hierarchical ADHD symptom count) but rather as being underpinned

approach and exclusion criteria can be problematic by multiple trait and disorder liabilities.45,46

because important features beyond the diagnosis of Alternatives to a traditional categorical diagnostic

primary interest might not be assessed and treated, or approach are being considered in the context of research.

For more on the Research considered in research studies. For example, prior to The Research Domain Criteria (R-DoC) project is one

Domain Criteria project see DSM-5, ADHD could not be diagnosed in the presence such research framework proposed by the NIMH.47 This

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/

of autism spectrum disorder.34 This has meant that project has been proposed as a means of investigating

research-priorities/rdoc/

constructs/rdoc-matrix.shtml many research studies did not assess both phenotypes mental disorders by conceptualising them as dimensional

or excluded those with both conditions until this notion constructs (eg, negative valence systems), which transcend

began to be challenged.35 Future intervention and diagnostic categories and integrate information across

outcome research on individuals with multiple multiple measurement levels (eg, genes, molecules, cells,

neurodevelopmental problems would be helpful in circuits, and self-reports). Although a dimensional

addressing this knowledge gap. framework is to be welcomed, and will be helpful for

some types of research (eg, bridging basic science and

Neurodevelopmental disorders conceptualised human cognitive and imaging research),48 as yet we do not

as traits have reliable methods for assessing many of the suggested

There is strong research evidence that favours the R-DoC dimensions and we also do not know how they

consideration of some neurodevelopmental disorders map onto complex, clinically relevant problems. It is

and diagnoses as lying at the extremes of important that this gap is spanned if research is going to

dimensions.14,36,37 For example, ADHD defined as a trait, inform clinical practice and clinical observations are to

typically using total symptom scores, behaves inform basic research.

dimensionally in terms of its association with adverse

outcomes38—there is no clearcut threshold beyond Consideration of developmental change and

which adverse outcomes emerge. Also, the same a life-span approach

genetic and early environmental risk factors that are Symptom decline but persistence to adult life

associated with a diagnosis of ADHD or autism Neurodevelopmental disorders are subject to matur-

spectrum disorder predict trait levels in the general ational change.2 Many child neurodevelopmental

population.39–43 However, categorical conceptualisation disorders typically improve with age and were previously

can be helpful for some purposes;4 for example, when considered to be childhood-limited problems. However,

dichotomous and potentially risky clinical decisions, follow-up studies show that although outcomes are

such as whether to prescribe medication to a child or variable, for many individuals, neurodevelopmental

not, have to be made. problems and diagnosis persist into adult life.1,29,49–52

4 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5

Personal View

Reported estimates of diagnostic persistence rates vary longitudinal characterisation of neurodevelopmental

widely and tend to be higher in patient samples than in disorder phenotypes across ages in unselected

population-based cohorts.53 For example, if we take the populations to examine patterns of onset, desistence, and

example of ADHD, one meta-analysis49 suggested a persistence across the lifespan. One challenge for such

15% ADHD diagnostic persistence rate to adult life. developmentally informative research is that both

Autism spectrum disorder, language impairments,54 and researchers and clinicians use different measures after

literacy-related difficulties55 also commonly persist in age 16–18 years and informants typically change from

many patients. Some core symptoms, for example ADHD- parent reporting during childhood to self-reporting in

related hyperactive-impulsiveness56 and autism spectrum adult life. One approach that might help bridge this gap

disorder-related behaviours29 decline considerably with between childhood and adult life is to encourage research

age. In recognition of this finding, the required number of investigations (and clinical services) that focus on

ADHD symptoms for a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD has transition ages (eg, ages 15–25 years).

been adjusted for adolescents and adults. However,

there are few service provisions for neurodevelopmental How clinicians and researchers might proceed

disorders in adult life.57,58 Adopt a conceptual approach

Our main conclusion is that regardless of what framework

Change in predominant manifestation is used for conceptualising neurodevelopmental or

Change does not simply involve a decline in core psychiatric disorders, there are problems if clinicians and

symptoms, since the predominant clinical manifestations researchers apply them rigidly without thought or critical

are also subject to change and new co-occurring problems, reflection; for example by counting up items generated by

such as substance misuse, can emerge.59 For example, a structured interview or generating a score (eg, ADI and

many patients who do not meet full diagnostic criteria for ADOS generated diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder).

ADHD or autism spectrum disorder in adult life have Thresholds for defining disorders, ie, the number of

sub-threshold persistence of core symptoms and a required symptoms, are arbitrary. Failing to recognising

broader range of cognitive, psychiatric (eg, mood disorder comorbidities or symptoms beyond the primary diagnosis

or substance misuse), and functional impairments of interest is another risk. Historically, such an approach

such as difficulties with employment or social has caused problems (for example, comorbid ADHD and

relationships.53,59,60 At present, there is very little known autism spectrum disorder being disallowed by DSM and

about potentially modifiable factors (eg, prenatal and ICD) for researchers and clinical practitioners. For

early life environmental enrichment and social example, a child might not meet the exact symptom cutoff

influences) that optimise neurodevelopmental outcomes for a diagnosis of ADHD but if they fall just below the

and these factors are an important area for future diagnostic threshold and symptoms are interfering with

research. Longitudinal observational designs will remain function, then behavioural and social approaches typically

important but other methods will then be required to test used for ADHD might be helpful.

causal hypotheses as discussed elsewhere.61 It is also important to adopt a developmental view

across the life-span; this requires longitudinal research

A life-course view approaches that bridge child and adult life and a clinical

Until recently, adult symptoms of neurodevelopmental perspective that goes beyond current presenting

disorders were assumed by most clinicians to be problems. The clinician is required to weigh up

a continuation from childhood-onset problems. An multiple factors when assessing patients, planning

intriguing finding from the Dunedin longitudinal cohort intervention, and predicting outcomes.65 Individuals

study53 challenges this assumption in relation to ADHD. with the same diagnosis might require different types

Moffitt and colleagues53 found that most cases of adult of intervention depending on co-occurring symptoms,

ADHD at age 38 years were not preceded by a childhood age, social context.

diagnosis. This finding has been replicated in

two independent adolescent or young adult samples.62,63 Consider complexity versus reductionism

The later-onset ADHD symptoms were not entirely We conclude that it is clinically helpful and scientifically

explained by concurrent or earlier comorbidities. This justified to group neurodevelopmental disorders but also

phenomenon cannot be explained satisfactorily by sub- necessary to retain diagnostic distinctions. Of course, we

threshold cases. The findings raise the question of what recognise there is enormous heterogeneity in symptoms,

this adult ADHD phenotype is. Is it the manifestation of outcome, and treatment response across all neuro-

symptoms suppressed earlier in life because of early developmental and psychiatric disorders and there are no

protective factors, or does it represent a different disorder clearcut boundaries between different disorders or

altogether with a different pathogenesis, akin to juvenile- between different groups of disorders. The strong overlap

onset and maturity-onset diabetes? These findings have and lack of distinction between disorders does not mean it

important implications for adult mental health services is necessarily helpful to completely dispense with

and for future research.64 There is a need for detailed diagnostic boundaries or groupings. Most clinicians will

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5 5

Personal View

Panel: Conceptualising neurodevelopmental disorders: Search strategy and selection criteria

a summary

This article is a Personal View and not a review; the authors

• Group and distinguish neurodevelopmental disorders identified papers according to their relevance to the

• Disaggregate beyond core diagnostic symptoms conceptual issues being discussed. Papers published were first

• Consider overall burden of psychopathology and identified by searches of PubMed from Jan 1, 2010 to

multi-morbidity March 31, 2016 using the search terms “ADHD”, “autism”,

• Consider importance of social context (demands, “ASD”, “communication”, “language“, “reading”, “spelling”,

resources, and risks) “tics”, “child”, “adult”, “longitudinal”, “comorbidity”,

• Take into account developmental change across the “multimorbidity”, “genetic”, “prenatal”, “aetiology”. Only

lifespan and maturational influences articles published in English were included. Reviews on

• Note that traits and categorical diagnoses are both useful neurodevelopmental disorders, book chapters, and NICE

• Note that it is unhelpful to dispense with diagnoses or guidelines published between Jan 1, 2012 and March 31, 2016

rigidly adhere to them and some older articles were also examined. Systematic

reviews on ADHD and autism are published elsewhere.

recognise that neurodevelopmental disorders are more

than a set of diagnostic criteria, and that multiple validity and value of diagnosis and on lumping together

impairments or multi-morbidity are the rule rather than versus splitting different forms of psychopathology in

exception. However, research funders, service funding addition to concerns and apologies about relying on

and planning, local assessment policies, and national reported symptoms. This is not helpful for practitioners

guidelines are not necessarily as flexible. Interventions are and patients.

not identical for different types of problems, so it is For current purposes they are reasonably reliable, useful

important that research captures these complex phenotype for communication and attempting to standardise

patterns and associated subthreshold symptoms, and treatment approaches, provided they are used sensibly as a

considers the social context and developmental factors framework (panel), rather than as fundamental truths; and

that are important in both research and clinical practice. they should not be used as the sole means of determining

This is achievable, and there are many examples of such patient care. For researchers, it is premature, in our view,

research, some of which we have already discussed.24,66 to dispense with diagnoses, but equally we need to

Complexity is the nature of clinical problems, so empirically and critically assess the value of alternatives.

perhaps it is better to acknowledge this complexity and Contributors

incorporate this into research designs if the gaps between AT and MC undertook the literature search. AT drafted the initial

neuroscience, mental health research, and real-life manuscript with MR. AT, MC, and MR contributed to revisions and the

final submitted draft.

clinical practice are ever to be bridged. Clinicians need to

apply clinical judgement as well as evidence and Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

guidelines, and researchers need to engage directly with

clinicians so that research is clinically meaningful. Acknowledgments

The authors’ research is funded by the MRC, ESRC, and Wellcome Trust.

We are grateful to Lucy Riglin, Stephan Collishaw and Kate Langley for

A neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosis is inadequate their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

as a means of rationing References

In our view, as patient expectations grow and resources 1 Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and

diminish,67 clinicians are being called on to make discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult

life. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47: 276–95.

decisions that affect resource allocation for a patient. It is 2 Thapar A, Rutter M. Neurodevelopmental disorders. In: Thapar A,

not reasonable for services or agencies to allocate Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling M, Taylor EA, eds. Rutter’s

intervention and support purely on the basis of a yes or Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 6th edn. Oxford: John Wiley

& Sons Limited, 2015: 31–40.

no diagnosis, including ones made after lengthy, 3 APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

protracted, and expensive assessments (eg, educational 5th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

support to be linked to a diagnosis of autism spectrum 4 Rutter M. Research review: child psychiatric diagnosis and

disorder). That is because an individual’s needs are not classification: concepts, findings, challenges and potential.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011; 52: 647–60.

best captured by diagnosis alone. Systematic and 5 Rutter M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Using sex differences in

validated methods for assessing the needs of children psychopathology to study causal mechanisms: unifying issues and

and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders beyond research strategies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003; 44: 1092–115.

6 Lichtenstein P, Carlström E, Råstam M, Gillberg C, Anckarsäter H.

diagnosis are needed to avoid those with subthreshold The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related

symptomatology but substantial impairment missing neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. Am J Psychiatry 2010;

out on vital service provision. 167: 1357–63.

7 NICE. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and

So do we dispense with diagnosis? We think not. There management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. 2016.

are long-standing arguments in psychiatry disputing the https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg72 (accessed July 27, 2016).

6 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5

Personal View

8 NICE. Autism: guidance and guidelines. 2014. 30 Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg128 (accessed July 27, 2016). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care,

9 The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet

of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. 2012; 380: 37–43.

Multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. 31 NICE. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management, 2011.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56: 1073–86. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127 (accessed July 27, 2016).

10 Bushe CJ, Savill NC. Systematic review of atomoxetine data in 32 Ollendick TH, Jarrett MA, Grills-Taquechel AE, Hovey LD, Wolff JC.

childhood and adolescent attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder Comorbidity as a predictor and moderator of treatment outcome in

2009–2011: focus on clinical efficacy and safety. J Psychopharmacol youth with anxiety, affective, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder,

2014; 28: 204–11. and oppositional/conduct disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;

11 Leckman JF, Bloch MH. Tic disorders. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, 28: 1447–71.

Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor EA, eds. Rutter’s Child 33 Reichow B, Volkmar FR, Bloch MH. Systematic review and

and Adolescent Psychiatry, 6th edn. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons meta-analysis of pharmacological treatment of the symptoms of

Limited, 2015: 757–73. attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with pervasive

12 Kanner L. The children haven’t read those books, reflections on developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2013; 43: 2435–41.

differential diagnosis. Acta Paedopsychiatr 1969; 36: 2–11. 34 APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders,

13 Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. 4th edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/ 35 Rommelse NNJ, Altink ME, Fliers EA, et al. Comorbid problems in

hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry 2005; ADHD: degree of association, shared endophenotypes, and

57: 1336–46. formation of distinct subtypes. Implications for a future DSM.

14 Thapar A, Cooper M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet J Abnorm Child Psychol 2009; 37: 793–804.

2016; 387: 1240–50. 36 Norbury CF. Practitioner review: social (pragmatic) communication

15 Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E. Emotion dysregulation disorder conceptualization, evidence and clinical implications.

in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2014; J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014; 55: 204–16.

171: 276–93. 37 Rutter M. Changing concepts and findings on autism.

16 Thapar A, van den Bree M, Fowler T, Langley K, Whittinger N. J Autism Dev Disord 2013; 43: 1749–57.

Predictors of antisocial behaviour in children with attention deficit 38 Bussing R, Mason DM, Bell L, Porter P, Garvan C. Adolescent

hyperactivity disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 15: 118–25. outcomes of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a

17 Still G. Some abnormal psychical conditions in children: diverse community sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry

the Goulstonian lectures. Lancet 1902; 159: 1008–12. 2010; 49: 595–605.

18 Simonoff E, Taylor E, Baird G, et al. Randomized controlled 39 Levy F, Hay DA, McStephen M, Wood C, Waldman I.

double-blind trial of optimal dose methylphenidate in children and Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: a category or a continuum?

adolescents with severe attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and Genetic analysis of a large-scale twin study.

intellectual disability. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013; 54: 527–35. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36: 737–44.

19 Ahuja A, Martin J, Langley K, Thapar A. Intellectual disability in 40 Martin J, Hamshere ML, Stergiakouli E, O’Donovan MC, Thapar A.

children with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr 2013; Genetic risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder contributes

163: 890–95. to neurodevelopmental traits in the general population.

20 Kreppner JM, O’Connor TG, Rutter M. Can inattention/overactivity Biol Psychiatry 2014; 76: 664–71.

be an institutional deprivation syndrome? J Abnorm Child Psychol 41 Stergiakouli E, Martin J, Hamshere ML, et al. Shared genetic

2001; 29: 513–28. influences between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

21 Weisz JR, Ng MY, Lau N. Psychological interventions: overview and traits in children and clinical ADHD.

critical issues for the field. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015; 54: 322–27.

Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor EA, eds. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent 42 Robinson EB, St Pourcain B, Anttila V, et al. Genetic risk for autism

Psychiatry, 6th edn. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2015: 461–82. spectrum disorders and neuropsychiatric variation in the general

22 Scott S. Oppositional and conduct disorders. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, population. Nat Genet 2016; 48: 552–55.

Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor EA, eds. Rutter’s Child 43 Mandy W, Lai MC. Annual Research Review: the role of the

and Adolescent Psychiatry, 6th edn. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons environment in the developmental psychopathology of autism

Limited, 2015: 913–30. spectrum condition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016; 57: 271–92.

23 Caye A, Spadini AV, Karam RG, et al. Predictors of persistence of 44 Craddock N, Mynors-Wallis L. Psychiatric diagnosis: impersonal,

ADHD into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature and imperfect and important. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204: 93–95.

meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016; 25: 1151–59. 45 Martin J, Hamshere ML, Stergiakouli E, O’Donovan MC, Thapar A.

24 Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Adult functional Neurocognitive abilities in the general population and composite

outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems: genetic risk scores for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

a prospective, longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015; 56: 648–56.

72: 892–99. 46 Shaw P, Malek M, Watson B, Greenstein D, de Rossi P, Sharp W.

25 Riglin L, Collishaw S, Thapar AK, et al. Association of genetic risk Trajectories of cerebral cortical development in childhood and

variants with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder trajectories in adolescence and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

the general population. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; published online Biol Psychiatry 2013; 74: 599–606.

Nov 2. DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2817. 47 Cuthbert BN. Research domain criteria: toward future psychiatric

26 Cuffe SP, Visser SN, Holbrook JR, et al. ADHD and psychiatric nosologies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015; 17: 89–97.

comorbidity: functional outcomes in a school-based sample of 48 Pine DS. Editorial: lessons learned on the quest to understand

children. J Atten Disord 2015; published online Nov 25. developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;

DOI:10.1177/1087054715613437. 51: 533–34.

27 Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Attentional difficulties in 49 Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of

middle childhood and psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up

J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997; 38: 633–44. studies. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 159–65.

28 Norén Selinus E, Molero Y, Lichtenstein P, et al. Childhood 50 Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and

symptoms of ADHD overrule comorbidity in relation to correlates of adult attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder:

psychosocial outcome at age 15: a longitudinal study. PLoS One meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194: 204–11.

2015; 10: e0137475. 51 Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children

29 Magiati I, Tay XW, Howlin P. Cognitive, language, social and with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45: 212–29.

behavioural outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: 52 Anderson DK, Liang JW, Lord C. Predicting young adult outcome

a systematic review of longitudinal follow-up studies in adulthood. among more and less cognitively able individuals with autism

Clin Psychol Rev 2014; 34: 73–86. spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014; 55: 485–94.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5 7

Personal View

53 Moffitt TE, Houts R, Asherson P, et al. Is adult ADHD a 61 Thapar A, Rutter M. Using natural experiments and animal models

childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder? Evidence from a to study causal hypotheses in relation to child mental health

four-decade longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2015; problems. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling M,

172: 967–77. Taylor EA, eds. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 6th edn.

54 Whitehouse AJ, Line EA, Watt HJ, Bishop DV. Qualitative aspects of Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2015: 145–62.

developmental language impairment relate to language and literacy 62 Agnew-Blais JC, Polanczyk GV, Danese A, Wertz J, Moffitt TE,

outcome in adulthood. Int J Lang Commun Disord; 44: 489–510. Arseneault L. Evaluation of the persistence, remission, and

55 Maughan B, Messer J, Collishaw S, et al. Persistence of literacy emergence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young

problems: spelling in adolescence and at mid-life. adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73: 713–20.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009; 50: 893–901. 63 Caye A, Rocha TB, Anselmi L, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity

56 Pingault B, Viding E, Galéra C, et al. Genetic and environmental disorder trajectories from childhood to young adulthood: evidence

influences on the developmental course of attention-deficit/ from a birth cohort supporting a late-onset syndrome.

hyperactivity disorder symptoms from childhood to adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73: 705–12.

JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 651–58. 64 Faraone SV, Biederman J. Can attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

57 Hall CL, Newell K, Taylor J, Sayal K, Hollis C. Services for young onset occur in adulthood? JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73: 655–66.

people with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder transitioning 65 Leckman JF, Taylor E. Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic

from child to adult mental health services: a national survey of Formulation. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S,

mental health trusts in England. J Psychopharmacol 2015; 29: 39–42. Snowling MJ, Taylor EA, eds. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent

58 Swift KD, Sayal K, Hollis C. ADHD and transitions to adult mental Psychiatry, 6th edn. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2015:

health services: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev 2014; 403–18.

40: 775–86. 66 Kreppner JM, Rutter M, Beckett C, et al. Normality and impairment

59 Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MA, et al. Clinical and following profound early institutional deprivation: a longitudinal

functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity follow-up into early adolescence. Dev Psychol 2007; 43: 931–46.

disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 1295–303. 67 Ham C, Dixon A, Brooke B. Transforming the delivery of health

60 Whitehouse AJ, Watt HJ, Line EA, Bishop DV. Adult psychosocial and social care: the case for fundamental change. London:

outcomes of children with specific language impairment, pragmatic The King’s Fund, 2012.

language impairment and autism. Int J Lang Commun Disord;

44: 511–28.

8 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online Deceber 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5

You might also like

- Iq and AdaptativeDocument27 pagesIq and AdaptativeRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- PSY-Mood DisordersDocument185 pagesPSY-Mood DisordersDelaNo ratings yet

- Lai, M.-C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015) - Identifying The Lost Generation of Adults With Autism Spectrum ConditionsDocument15 pagesLai, M.-C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015) - Identifying The Lost Generation of Adults With Autism Spectrum ConditionsTomislav Cvrtnjak100% (1)

- Neuro Developmental Treatment (NDT) For Cerebral Palsy: - A Clinical StudyDocument2 pagesNeuro Developmental Treatment (NDT) For Cerebral Palsy: - A Clinical StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Public Health DirectoryDocument7 pagesPublic Health DirectoryAyobami OdewoleNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Psychiatric Comorbidities Recognition Management (Oxford Psychiatry Library Series) (David J. Castle, Peter F. Buckley Etc.) (Z-Library)Document156 pagesSchizophrenia and Psychiatric Comorbidities Recognition Management (Oxford Psychiatry Library Series) (David J. Castle, Peter F. Buckley Etc.) (Z-Library)Emier Zulhilmi100% (1)

- Vitals Chart - PedsCases Notes - 1 PDFDocument1 pageVitals Chart - PedsCases Notes - 1 PDFYousef Hassan BazarNo ratings yet

- Dr. Andrew Moulden Interview - What You Were Never Told About VaccinesDocument16 pagesDr. Andrew Moulden Interview - What You Were Never Told About VaccinesTiffany Torres100% (1)

- Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral PalsyDocument11 pagesEarly, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral PalsyRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Neurofeedback AdhdDocument8 pagesNeurofeedback AdhdAlbertoNo ratings yet

- Natural Hygiene Part 2 - The Miracle of FastingDocument3 pagesNatural Hygiene Part 2 - The Miracle of Fastingraweater75% (4)

- Grocery Cashiers: Serving Customers Shouldn't Hurt YouDocument8 pagesGrocery Cashiers: Serving Customers Shouldn't Hurt YouGS Lage GraphicsNo ratings yet

- Autism NeuroscienceDocument10 pagesAutism NeuroscienceAnonymous aCmwhRdNo ratings yet

- Nonepileptic Seizures Treatment Workshop Summary: ReviewDocument11 pagesNonepileptic Seizures Treatment Workshop Summary: ReviewEmmaNo ratings yet

- What Are Neurodevelopmental DisordersDocument6 pagesWhat Are Neurodevelopmental DisordersMario SalmanNo ratings yet

- 001 - Best of Neuroscience - V3Document35 pages001 - Best of Neuroscience - V3Vladan BajicNo ratings yet

- Rheumatology: Differential Diagnoses of ArthritisDocument3 pagesRheumatology: Differential Diagnoses of ArthritisSok-Moi Chok100% (1)

- Welcome Letter For FamiliesDocument3 pagesWelcome Letter For FamiliesChild and Family InstituteNo ratings yet

- Articulo 14Document3 pagesArticulo 14Vilma HernandezNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Mccutcheon 2019 SchizophreniaDocument10 pagesJamapsychiatry Mccutcheon 2019 Schizophreniavaleria.correa1No ratings yet

- Tuberosu SlerosisDocument13 pagesTuberosu SlerosisAbdul SadiqNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry 2019 3360Document10 pagesJamapsychiatry 2019 3360Furqan BansirNo ratings yet

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: BMJ (Online) September 2006Document7 pagesObsessive-Compulsive Disorder: BMJ (Online) September 2006adriantiariNo ratings yet

- Epigenetics and ADHDDocument26 pagesEpigenetics and ADHDJulius Cesar RomanNo ratings yet

- 668 FullDocument10 pages668 FullfranciscoNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder in ICD 11: A New Disorder or ODD With A Specifier For Chronic Irritability?Document2 pagesDisruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder in ICD 11: A New Disorder or ODD With A Specifier For Chronic Irritability?Rafael MartinsNo ratings yet

- A Proposed Solution To Integrating Cognitive-Affective Neuroscience and Neuropsychiatry in Psychiatry Residency Training The Time Is NowDocument6 pagesA Proposed Solution To Integrating Cognitive-Affective Neuroscience and Neuropsychiatry in Psychiatry Residency Training The Time Is NowafpiovesanNo ratings yet

- Attention Defi Cit Hyperactivity Disorder: SeminarDocument11 pagesAttention Defi Cit Hyperactivity Disorder: SeminarCristinaNo ratings yet

- Neuromodulation For The Treatment of Prader-Willi Syndrome - A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesNeuromodulation For The Treatment of Prader-Willi Syndrome - A Systematic ReviewCristina Sánchez MoralesNo ratings yet

- Obsessive Compulsivedisorder (OCD) PracticalstrategiesDocument12 pagesObsessive Compulsivedisorder (OCD) PracticalstrategiesAF KoasNo ratings yet

- Refining Delirium: A Transtheoretical Model of Delirium Disorder With Preliminary Neurophysiologic SubtypesDocument12 pagesRefining Delirium: A Transtheoretical Model of Delirium Disorder With Preliminary Neurophysiologic SubtypesArsyaFirdausNo ratings yet

- Revisiting The Etiological Aspects of Dissociative Identity Disorder: A Biopsychosocial PerspectiveDocument10 pagesRevisiting The Etiological Aspects of Dissociative Identity Disorder: A Biopsychosocial Perspectivetitinmaulina06No ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Research: Xavier Benarous, Marie Raf Fin, Vladimir Ferra Fiat, Angèle Consoli, David CohenDocument12 pagesSchizophrenia Research: Xavier Benarous, Marie Raf Fin, Vladimir Ferra Fiat, Angèle Consoli, David CohenJorge SalazarNo ratings yet

- McCarthy CBMH 2020Document14 pagesMcCarthy CBMH 2020ArRa Za (Arra)No ratings yet

- Annett - Et - Al-2015-Pediatric - Blood - & - Cancer 2Document54 pagesAnnett - Et - Al-2015-Pediatric - Blood - & - Cancer 2KarolinaMaślakNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy: Nature Reviews Disease Primers January 2016Document25 pagesCerebral Palsy: Nature Reviews Disease Primers January 2016Firdaus BillyNo ratings yet

- Niemann 36Document20 pagesNiemann 36banitavlad5No ratings yet

- Conduct Disorders: European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry December 2012Document7 pagesConduct Disorders: European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry December 2012Akanksha SinghNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy: Nature Reviews Disease Primers January 2016Document25 pagesCerebral Palsy: Nature Reviews Disease Primers January 2016Zerry Reza SyahrulNo ratings yet

- Personal View: Graham Teasdale, Andrew Maas, Fiona Lecky, Geoff Rey Manley, Nino Stocchetti, Gordon MurrayDocument11 pagesPersonal View: Graham Teasdale, Andrew Maas, Fiona Lecky, Geoff Rey Manley, Nino Stocchetti, Gordon MurrayMariana PeredaNo ratings yet

- Conduct Disorders: European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry December 2012Document7 pagesConduct Disorders: European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry December 2012hopeIshanzaNo ratings yet

- Staging in Bipolar Disorder: From Theoretical Framework To Clinical UtilityDocument9 pagesStaging in Bipolar Disorder: From Theoretical Framework To Clinical UtilitySi Se Puede NomasfotomultasNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Neuropsychiatry: A Case-Based ApproachFrom EverandPediatric Neuropsychiatry: A Case-Based ApproachAaron J. HauptmanNo ratings yet

- Caspi Et Al The P Factor One General Psychopathology Factor in The Structure of PsychiatricDocument19 pagesCaspi Et Al The P Factor One General Psychopathology Factor in The Structure of PsychiatricAlejandro CaraveraNo ratings yet

- Early, Accurate Diagnosis of Cerebral PalsyDocument11 pagesEarly, Accurate Diagnosis of Cerebral PalsyAndrea PederziniNo ratings yet

- Model For Pediatric Neurocognitive Interventions - LimondDocument20 pagesModel For Pediatric Neurocognitive Interventions - LimondAdriana BritoNo ratings yet

- Paulea - Rowlandb.fergusona - Chelonisc.tannockd - Swansone.castellanos. ADHD Characteristics Interventions ModelsDocument21 pagesPaulea - Rowlandb.fergusona - Chelonisc.tannockd - Swansone.castellanos. ADHD Characteristics Interventions ModelsRute Almeida RomãoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673612612689 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0140673612612689 MainOana OrosNo ratings yet

- Classification of Mental Disorders: A Global Mental Health PerspectiveDocument4 pagesClassification of Mental Disorders: A Global Mental Health PerspectiveKabeloNo ratings yet

- Martian, Et Al., (2012) - Avances en Enfoques Multidisciplinarios y en Diversas Especies para El Examen de La Neurobiología de Los TrastoDocument12 pagesMartian, Et Al., (2012) - Avances en Enfoques Multidisciplinarios y en Diversas Especies para El Examen de La Neurobiología de Los TrastoGlo RisNo ratings yet

- Hackett 2014Document10 pagesHackett 2014Luisa BragançaNo ratings yet

- Different Subtypes of DyskineticDocument8 pagesDifferent Subtypes of DyskineticMariana CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Neuropsicologia en Cancer PediatricoDocument7 pagesNeuropsicologia en Cancer PediatricoNinaNo ratings yet

- The Schizophrenia Syndrome, Circa 2024Document28 pagesThe Schizophrenia Syndrome, Circa 2024Khaled AbdelNaserNo ratings yet

- An Update On Psychopharmacological TreatDocument15 pagesAn Update On Psychopharmacological Treatzakayahz3103No ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Stigma in Mental Health Professionals and Associated Factors A Systematic ReviewDocument1 pageSchizophrenia Stigma in Mental Health Professionals and Associated Factors A Systematic ReviewFrida Ximena Perez CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Mol Med Clin PsychDocument9 pagesMol Med Clin PsychalondraNo ratings yet

- Dissociative Identity Disorder: An Empirical OverviewDocument16 pagesDissociative Identity Disorder: An Empirical OverviewJosé Luis SHNo ratings yet

- Autism Pathogenesis 2Document18 pagesAutism Pathogenesis 2Prateek Kumar PandaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0149763417301732 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0149763417301732 MainAlkindoNo ratings yet

- Medical Comorbidities in Children and AdolescentsDocument12 pagesMedical Comorbidities in Children and AdolescentsSalud-psicología-psiquiatria DocenciaNo ratings yet

- McDiarmad Et Al (2017)Document20 pagesMcDiarmad Et Al (2017)jorge9000000No ratings yet

- Neuropsychological AssessmentDocument1 pageNeuropsychological AssessmentNavneet DhimanNo ratings yet

- Consensus: StatementDocument15 pagesConsensus: StatementPriscilla Gonzalez FernandoNo ratings yet

- Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging - Neuroimaging of The Child With Developmental DelayDocument18 pagesTopics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging - Neuroimaging of The Child With Developmental DelayJemima ChanNo ratings yet

- Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy Advances in Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument11 pagesEarly, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy Advances in Diagnosis and TreatmentMiguel Angel Rodriguez MartinezNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Professional Teachers On Padang Vocational School Students' Achievement - ScienceDirectDocument16 pagesThe Influence of Professional Teachers On Padang Vocational School Students' Achievement - ScienceDirectRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- From Digital Literacy To Digital Competence: The Teacher Digital Competency (TDC) Framework - SpringerLinkDocument66 pagesFrom Digital Literacy To Digital Competence: The Teacher Digital Competency (TDC) Framework - SpringerLinkRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Full Article: Collaborative Learning Practices: Teacher and Student Perceived Obstacles To Effective Student CollaborationDocument63 pagesFull Article: Collaborative Learning Practices: Teacher and Student Perceived Obstacles To Effective Student CollaborationRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Aligning Teacher Competence Frameworks To 21st Century Challenges: The Case For The European Digital Competence Framework For Educators (DDocument33 pagesAligning Teacher Competence Frameworks To 21st Century Challenges: The Case For The European Digital Competence Framework For Educators (DRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Intelligence Quotient (Iq) and Sex: Predictors of Academic Performance, Emotional State, Social Adaptability and Work AttitudeDocument14 pagesIntelligence Quotient (Iq) and Sex: Predictors of Academic Performance, Emotional State, Social Adaptability and Work AttitudeRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Adaptative and Social AbilityDocument10 pagesAdaptative and Social AbilityRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Michael Esterman2020Document13 pagesMichael Esterman2020Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- BMC Medical EducationDocument31 pagesBMC Medical EducationRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Opel 2020Document9 pagesOpel 2020Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Antoniou 2021Document15 pagesAntoniou 2021Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- UNF Digital Commons UNF Digital Commons: University of North Florida University of North FloridaDocument53 pagesUNF Digital Commons UNF Digital Commons: University of North Florida University of North FloridaRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Shuang 2021Document7 pagesShuang 2021Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Alvares 2019Document12 pagesAlvares 2019Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Validation of The NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery in Intellectual DisabilityDocument13 pagesValidation of The NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery in Intellectual DisabilityRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Changes in College Student Endorsement of ADHD Symptoms Across DSM EditionDocument12 pagesChanges in College Student Endorsement of ADHD Symptoms Across DSM EditionRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Neuropsychological Functioning Between Adults With Early-And Late-Onset DSM-5 ADHDDocument12 pagesComparison of Neuropsychological Functioning Between Adults With Early-And Late-Onset DSM-5 ADHDRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Tdah 4Document9 pagesTdah 4Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Tdah 3Document14 pagesTdah 3Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Pathogenic Yield of Genetic Testing in Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument11 pagesPathogenic Yield of Genetic Testing in Autism Spectrum DisorderRaul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- 10 1192@bjp 2020 152Document8 pages10 1192@bjp 2020 152Raul Morales VillegasNo ratings yet

- Safety and Activity of The Immune Modulator HE2000 On The Incidence of Tuberculosis and Other Opportunistic Infections in AIDS PatientsDocument3 pagesSafety and Activity of The Immune Modulator HE2000 On The Incidence of Tuberculosis and Other Opportunistic Infections in AIDS PatientsJosueNo ratings yet

- Sutures India Truseal Tissue Adhesive - Gloria Exports EnterpriseDocument4 pagesSutures India Truseal Tissue Adhesive - Gloria Exports EnterpriseJaviera FerradaNo ratings yet

- BronchiectasisDocument17 pagesBronchiectasisBharat GaikwadNo ratings yet

- Pin Infection Grading SystemDocument1 pagePin Infection Grading SystemAlok SinghNo ratings yet

- Efeito Da Informação Prévia Face-A-face Sobre A Ansiedade de Pacientes Submetidos À ExodontiaDocument12 pagesEfeito Da Informação Prévia Face-A-face Sobre A Ansiedade de Pacientes Submetidos À ExodontiaMylla FernandaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 Narayana Hrudayalaya Heart Hospital: Cardiac Care For The PoorDocument4 pagesCase Study 1 Narayana Hrudayalaya Heart Hospital: Cardiac Care For The PoorshwetaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan National Hepatitis Elimination Profile-FINALDocument12 pagesPakistan National Hepatitis Elimination Profile-FINALJawad NaqviNo ratings yet

- NCP AgnDocument2 pagesNCP AgnMichael Vincent DuroNo ratings yet

- Carillo vs. People G.R. No. 86890 FULL TEXTDocument8 pagesCarillo vs. People G.R. No. 86890 FULL TEXTJeng PionNo ratings yet

- Nclex TipsDocument1 pageNclex TipsMonika Mooney SwangerNo ratings yet

- Annexure B BDS Regulations 2022 3-6-2022Document349 pagesAnnexure B BDS Regulations 2022 3-6-2022Pramod JaliNo ratings yet

- SikaGrout 215 SDS en - MYDocument9 pagesSikaGrout 215 SDS en - MYMarhendraNo ratings yet

- AVPUDocument2 pagesAVPUAnissa Citra DewiNo ratings yet

- Aim 6 - Cycle 07 - Lesson 05 - TeachingDocument7 pagesAim 6 - Cycle 07 - Lesson 05 - TeachingMai UyênNo ratings yet

- Update On The Management of Overactive BladderDocument9 pagesUpdate On The Management of Overactive BladderMisna AriyahNo ratings yet

- 10 Squamouspapilloma-ReportoftwocasesDocument7 pages10 Squamouspapilloma-ReportoftwocasesAyik DarkerThan BlackNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training ActDocument22 pagesPalliative Care and Hospice Education and Training ActRuss Latino100% (1)

- A Review of Orthodontic Indices: DR Alka Gupta, DR Rabindra Man ShresthaDocument7 pagesA Review of Orthodontic Indices: DR Alka Gupta, DR Rabindra Man ShresthaJasmine PangNo ratings yet

- NHS-FPX6008 - Assessment 1-1Document6 pagesNHS-FPX6008 - Assessment 1-1RuthNo ratings yet

- HYPERTENSION INTERVENTION PLAN 1 FinalDocument6 pagesHYPERTENSION INTERVENTION PLAN 1 FinalKenrick Espiritu BajaoNo ratings yet

- Annual Medical Report FormDocument6 pagesAnnual Medical Report FormDarryl RoblesNo ratings yet

- Sepsis Syndromes in Adults: Epidemiology, Definitions, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and PrognosisDocument1 pageSepsis Syndromes in Adults: Epidemiology, Definitions, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and PrognosisFredghcNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation in Rheumatic DiseasesDocument5 pagesRehabilitation in Rheumatic DiseasesShahbaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Review of Immunology: ImmunityDocument8 pagesReview of Immunology: ImmunityChan SorianoNo ratings yet