Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Night Nasser Nationalised The Suez Canal

Uploaded by

Nick Soulas0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views10 pagesOriginal Title

The Night Nasser Nationalised the Suez Canal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views10 pagesThe Night Nasser Nationalised The Suez Canal

Uploaded by

Nick SoulasCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

The night Nasser

nationalised the

Suez canal

BY JEAN LACOUTURE & SIMONE LACOUTURE

A LMOST seve

n in the evening, and

night is slowly falling

over Alexandria’s vast

Mohammed Ali Square,

where a well-behaved

crowd is hemmed in by

police cordons. A

pleasant breeze is

blowing, raising the

spirits of all gathered

here, especially as we

have just endured one

of the hottest weeks on

record. We are standing

on a balcony where

President Gamal Abdel

Nasser will soon deliver

a speech. It’s only 20

metres from where

Muhammad Abed al-

Latif, a member of the

Muslim Brotherhood,

fired eight shots at

Nasser (as “an agent of

Anglo-American

imperialism”) two years

before.

The Egyptian president

appears, walks past us

and climbs to the

rostrum. Apparently

unconcerned by any

memory of the attack,

Nasser smiles a little.

He takes the

microphone and begins

to address the crowd.

This is not the sort of

speech people are used

to. What are we to make

of his popular, even

vulgar, baladi tone?

The crowd hangs on his

every word, every

nuance. His up-beat

tone wins them over.

We came here

expecting a monologue

with tragic overtones;

instead we are getting

comic relief.

“Now I just want to

mention the problems

I’ve had with the

American diplomatic

corps.” Nasser, usually

austere, adopts the

mocking tone of

Egypt’s satirical

songwriters and the

language of the poor.

The crowd bursts out

laughing.

“A US diplomat told me

this: if

Mr Allen (1) delivers a

State Department

message to you about

Czech arms sales (2),

you’ve got to send him

packing. But if he

returns to the US

without relaying the

message, Mr Dulles will

send Mr Allen

packing.” Nasser is

acting, relishing his role

as the cunning

Goha (3) battling

foreign behemoths.

Surprised by this style,

some Egyptian

journalists are

murmuring “kuwais

awi” (very good) under

their breath. This timid,

self-conscious man has

finally discovered how

to speak to the people

— with humour. Waves

of laughter, not angry

cries, well up from the

darkness of the square.

Nasser’s tone starts to

change as he outlines

the troubles he has had

with Eugene Black, the

World Bank

president (4). He makes

a bizarre observation:

“Mr Black reminded me

of Ferdinand de Lesseps

[the Frenchman who

designed the Suez

Canal].” Nasser

pronounces the surname

as a hiss.

The speech reaches a

crescendo. Bitter,

vicious and furious,

Nasser rails against “the

imperialists who have

mortgaged our future”.

At first the crowd reacts

tentatively, expecting

Nasser to end his anti-

US diatribe by

announcing pro-Soviet

action. So why has he

invoked de Lesseps?

“We will reclaim the

profits that this

imperialist company —

this state-within-a-state

—made while we were

starving to death.”

People on the official

platform and down

below are applauding

rapturously; they are

stunned and bewildered.

“I would like to

announce that the

Official Gazette is at

this very moment

publishing a statute

nationalising the Suez

Canal Company. At this

very moment

government agents are

taking possession of the

Company’s offices!”

People around us and in

the vast darkness below

react fervently.

Journalists once

sceptical of Nasser’s

regime stand on their

chairs and shout. Nasser

is suddenly overcome

by uncontrollable

laughter; his

announcement is so

shocking, his audacity

incredible. He goes on:

“The Suez Canal will

pay for the Aswan dam

project. Four years ago,

King Farouk fled this

country from this spot.

Tonight I am wresting

control of the Company

on behalf of the

Egyptian people.

Tonight the Suez Canal

will be managed by

Egyptians!” Nasser’s

words and laughter are

drowned by a

groundswell of cheering

and yelling. He drags

himself away from the

rostrum; the few foreign

observers look on in

amazement. Never has a

man thrown himself

into so risky a mission

with such delight.

Thirty minutes earlier,

Egyptian radio had

broadcast that sentence:

“Mr Black reminded me

of Ferdinand de

Lesseps.” Army units

responded to the pre-

arranged signal and

occupied the Suez

Canal Company’s

headquarters in Cairo

and offices in Ismailia,

Port Said, Port Tewfik

and Suez. The military

operation had an almost

un-Egyptian precision.

Mr Ménessier, the

Company’s senior

administrative officer,

was an “honoured

guest” at the Ismailia

governor’s office,

where he listened to the

broadcast of Nasser’s

announcement. Ecstatic

residents of Alexandria

ran along the corniche

as trucks with

loudspeakers drove

around blaring the

speech. The British

warship Jamaica,

moored in Alexandria’s

harbour as part of a

courtesy visit,

dampened the

enthusiasm of some

residents. “It’s a

courageous step, but

God help us all,” said a

friend.

We witnessed the

frenzy in Cairo two

days later when Egypt’s

hero returned. What a

contrast between the

formerly timid

technocrat and the man

who now stood above

the cheering crowd,

waving his arms as if

shipwrecked in a sea of

rapturous people: he

was like a boxing

champion returning in

triumph to his

childhood home. We

heard the same

comments everywhere,

from poor cafés to

middle-class salons:

“Nasser did it! He beat

countries that tried to

destroy him. Egypt has

waited a long time for

this! We must show our

support!”

Similar sentiments were

expressed by the

opposition, including

the nationalists of the

Wafd party, Muslim

Brotherhood

sympathisers and

landowners who had

been victims of

Nasser’s agrarian

reform. The Communist

party and friends were

delirious. The only

reservations were from

people over 50 who

followed the British

press and were troubled

by the intensity of

reactions in London.

But the people we

spoke to asked: “What

can you do about it?”

Were they anxious? It

seemed not.

JEAN LACOUTURE

Jean Lacouture is a

historian and author

most recently of ‘Gamal

Abdel Nasser’

(Bayard/BNF, Paris,

May 2005)

SIMONE LACOUTURE

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Innovation Power: How Technology Will Reshape GeopoliticsDocument216 pagesInnovation Power: How Technology Will Reshape GeopoliticsLê Tự Huy HoàngNo ratings yet

- (Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) Ranabir Samaddar (Auth.) - Karl Marx and The Postcolonial Age-Palgrave Macmillan (2018)Document328 pages(Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) Ranabir Samaddar (Auth.) - Karl Marx and The Postcolonial Age-Palgrave Macmillan (2018)JOSÉ MANUEL MEJÍA VILLENANo ratings yet

- Aznar vs. COMELEC DigestDocument1 pageAznar vs. COMELEC DigestChow Galan50% (2)

- Civic CenterDocument30 pagesCivic CenterKhea Micole May100% (3)

- David Wen-Wei Chang (Auth.) - China Under Deng Xiaoping - Political and Economic Reform-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1988)Document324 pagesDavid Wen-Wei Chang (Auth.) - China Under Deng Xiaoping - Political and Economic Reform-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1988)Alex SalaNo ratings yet

- Consti 2 Cases Jan 26, '18Document7 pagesConsti 2 Cases Jan 26, '18Rafael AdanNo ratings yet

- BT TACN Week 4Document4 pagesBT TACN Week 4Phương Anh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- INDIA Poltical Map PDFDocument1 pageINDIA Poltical Map PDFSamarth PradhanNo ratings yet

- WP31 0Document32 pagesWP31 0Archita JainNo ratings yet

- YoungScholars MPSDocument8 pagesYoungScholars MPSJelena CulibrkNo ratings yet

- Application For The Post of Assistant Engineer (Electrical) (Post Code:1/19)Document1 pageApplication For The Post of Assistant Engineer (Electrical) (Post Code:1/19)SAURAV ABHINo ratings yet

- Consortium of National Law Universities: Provisional 5th List - CLAT 2021 - PGDocument3 pagesConsortium of National Law Universities: Provisional 5th List - CLAT 2021 - PGLNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Shakespeare and RaceDocument12 pagesResearch Paper Shakespeare and Raceapi-397497836No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument265 pagesUntitledValeriaNo ratings yet

- Local Self GovernanceDocument155 pagesLocal Self GovernanceAshutosh Dubey AshuNo ratings yet

- August 2018 Pharmacist Licensure Examination: Seq. NODocument4 pagesAugust 2018 Pharmacist Licensure Examination: Seq. NOPRC BoardNo ratings yet

- Starkville Dispatch Eedition 3-8-20Document24 pagesStarkville Dispatch Eedition 3-8-20The DispatchNo ratings yet

- What Inspired The New England Confederation?Document11 pagesWhat Inspired The New England Confederation?Arsalan SheikhNo ratings yet

- Spomenici Su Proslost I Buducnost PolitDocument25 pagesSpomenici Su Proslost I Buducnost PolitFilip GalicNo ratings yet

- Second Home ComingDocument19 pagesSecond Home ComingKelly Jane ChuaNo ratings yet

- Pippa Norris - A Virtuous CircleDocument46 pagesPippa Norris - A Virtuous CircleMarina UrmanNo ratings yet

- Shaping The American Woman - Feminism and Advertising in The 1950Document13 pagesShaping The American Woman - Feminism and Advertising in The 1950Ninda Putri AristiaNo ratings yet

- Introduccion GREEN STEINDocument14 pagesIntroduccion GREEN STEINFrancoPaúlTafoyaGurtzNo ratings yet

- IV Classwise Students ListDocument8 pagesIV Classwise Students ListAjinkya MukhedkarNo ratings yet

- Elections ESL BritishDocument3 pagesElections ESL BritishRosana Andres DalenogareNo ratings yet

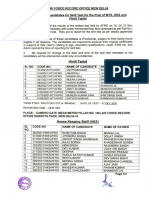

- Air Force Record Office New Delhi Short Listed Candidates For Skill Test For The Post of MTS. HKS and Hindi TypistDocument3 pagesAir Force Record Office New Delhi Short Listed Candidates For Skill Test For The Post of MTS. HKS and Hindi TypistSingh35No ratings yet

- From One Generation To The Next Armed SeDocument24 pagesFrom One Generation To The Next Armed SeAri El VoyagerNo ratings yet

- "Patriarchy:" Analysis: OppressionDocument21 pages"Patriarchy:" Analysis: OppressionMichi chenNo ratings yet

- El CondeDocument3 pagesEl CondeLalaineMackyNo ratings yet

- Imagining The Balkans Imagining The BalkDocument3 pagesImagining The Balkans Imagining The BalkBesnik EminiNo ratings yet