Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brand Communication & New Media: CHAPTER 7

Brand Communication & New Media: CHAPTER 7

Uploaded by

Sofia Biagi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views4 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views4 pagesBrand Communication & New Media: CHAPTER 7

Brand Communication & New Media: CHAPTER 7

Uploaded by

Sofia BiagiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

CHAPTER 7

APPROACHES TO DATA ANALYSIS, INTERPRETATION AND THEORY BUILDING FOR

SCHOLARY RESEARCH

Gathering and using qualitative data are deeply intertwined. From the moment you start collecting

qualitative data, you can (and should) begin the process of analysing it. Analysis involves looking for

patterns. Looking for patterns within and across individual elements of data as you collect data is vital

because it will influence how your research project unfolds. The patterns you see may suggest new

questions, bodies of literature to read and ways to use data you are collecting.

Theory means a system of ideas or statements explaining some phenomenon . Theory building means

identifying new concepts, constructs or processes that help us understand something about the

phenomenon; identifying new variants in a phenomenon and the factors that help understand and

explain them; identify exception that delineate when an existing theory is relevant and challenging the

adequacy of existing theory.

ANALYSING DATA

The fundamental step in your data analysis is coding. Coding means discerning small elements in your

data that can retain meaning if lifted out of context. Codes are concepts and these concepts vary in their

concreteness/ abstractness as well as in their emic/etic nature. Another way of describing coding is

reducing data into meaningful segments and assigning names to those segments.

It is critical to immerse yourself in the entire dataset so that you are familiar with the context before you

start to code

Emic= it draws directly on language used by the people being studied

Etic code= language ad concepts that are not necessarily those of people we study but that seem

appropriate to us within our scholarly field of interest.

Codes can be assigned to individual words, sentences, paragraphs or chunks of text of varying

lengths. Multiple codes can be applied to the same text.

Coding is iterative. The process typically involves generating an initial set of codes within a dataset. As

codes emerge you have to go back recode material that ou considered previously. The next step is

examine the set of codes to see which can be collapsed into slightly more abstract categories or

expanded into finer codes.

Tips:

1. Be alert to metaphors. They can help you figure out how people are making sense of their own

reality

2. Look for indicators of strong emotions. They provide simple clues as to what is important to

those who have produced whatever text you’re analysing

3. Listen (watch out). For phrases you have heard in other contexts that seem to be “imported”

into the context you are studying, like the phrase “scarce resource”.

4. Identify categories of actors who matter in the context you are studying. Thinking about

this may lead you to identify other categories of actors, or to code the types of inter-

dependencies that may exist or may be perceived as causing conflict between your actors in your

context.

5. Notice the kind of actions that are taken or contemplated.

Being alert to actions that are commonly taken or contemplated can also sensitise you to actions

that are rare or that are considered illegitimate.

6. Consider motive that lie behind the production of the text you are coding.

7. Probe for contradictions.

Contradictions may be found between seemingly incompatible elements of the text you are

coding, or portions of the text ay contradict assumptions you had made prior t starting the

research.

Coding puzzles like this can help you think out what other data you might need to collect to solve the

puzzle, and might open up new research questions for consideration.

The initial and ongoing coding can be influenced both y the data itself and by:

your initial research purpose or research question

prior literature relevant to your research question; and

the qualitative research tradition in which you are working

One of the best reasons for letting research questions influence the codes you consider is that it helps

you to know of your questions can or cannot be addressed through the data you have collected.

PRIOR LITERATURE AND CODING.

Looking at literature that relates to your research question before, during, and after data collection.

Looking to the prior literature for codes obviously opens you up to the potential pitfall of “force-fitting”

data. Further, there is the risk that seeing tings through the filters of prior research will blind you to

original codes and ultimately original insights. However, the risks associated with not knowing

what’s in the prior literature far outweigh any benefit you might have from ignoring it. You risk “

reinventing the wheel “. Further, you risk not seeing how your work can extend or even challenge

assumptions that have been made in prior literature.

INTERPRETATION AND THEORY BUILDING.

The emphasis shifts from identifying patterns in the data to attempting to find meaning in the patterns.

We have to keep in mind that even though we present analysis, interpretation and theory building as a

linear process, in practice you may expand codes, contract them, and revise them as interpretation and

theory building progress. You may also tack back and forth between the data, the codes, the literature

and your emerging theory. And you may also have eureka moments along the way when minor

epiphanies send you back to revamp your coding and test an emerging interpretation.

LOOKING FOR VARIATION

You can start to look for variation in your data. What we mean is seeking differences between one

group and another in terms of the codes you associate with them. Where you look for variation depends

on project. If you have collected interview data from a group of individuals, you might think about

salient sociological or demographic characteristics that differ between them, such as social class age,

age, or gender, and see whether the codes that occur in data collected differ between those in one

category versus another. If you are conducting a multi-sited inquiry whether the codes you associate

with data collected from one local differ from those you have associated with data collected from

another.

LOOKING FOR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CODES: ELEMENTS OF PHENOMENA,

PROCESSES, AND OUTCOMES.

The process of grouping lower order codes into higher order codes entails looking for relationships

between codes. But you can push further by considering how higher order codes elate to one another in

meaningful ways. In addition we have to distinguish between open coding and axial coding. When they

use the term axal coding, they mean looking in the data for concepts or constructs that would be related

to the central phenomenon or construct under investigation. This is useful advice even if you are not

“doing” grounded theory. Generally speaking there are three ways that codes you have identified ca

relate to one another. First, codes can be related to one another because they comprise distinct

dimensions of the same construct , or distinct elements of the same phenomenon if you prefer such

terminology. Second, they can be related to one another as steps, stages, phases or elements in a process.

Third, they can be related to one another in an explanatory fashion: that is, they can be linked based on

the premise that some codes can be interpreted as helping to understand why a focal phenomenon exists

or has particular characteristics, while others are seen as being explained by, or being a consequence of

or response to that focal phenomenon.

Elements of phenomena.

Ts identification of the dimensions of the experience of desires constitutes a clarification of the nature of

desire as a phenomenon or construct: “mapping” a construct, is particularly valuable when constructs

have a “ analytical generalisability”

Processes

Processes theories provide explanations in terms of the sequence of events leading to an outcome.

Temporal ordering in central to process theories.

Understanding conditions that give rise to a phenomenon or the consequences precipitated by a

phenomenon.

These kinds of theories are essentially variance theories, in that they help us understand the conditions

under which a phenomenon will/will not occur or the consequences that are likely to come about when a

phenomenon occurs versus when it does not. It is important to stress that when qualitative researchers

develop such explanatory theories by looking at relationship between coded categories of data, they

pretty consistently make it clear that they are not suggesting that human behaviour can ever be wholly

predicted or fully shaped by a finite set of factors.

DRAWING ON PRE-EXISTING THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES.

Increasingly qualitative scholars are turning to pre-existing theory to help them develop their own

unique conceptual insights into the things they study. When we use the term ”pre existing theoretical

perspective” we do not simply mean “the prior literature”. Rather, we refer to a set of concepts or a

more fully developed theory that has been advanced by earlier scholars to explain a range of

phenomena. The first theoretical perspective is the semiotic square, which is a mean of analysing paired

concepts in a system of thought or language. Furthermore, Greimas proposed that concepts might relate

to one another not just as binary opposites, but in a range of other ways.

For example, Rob used a semiotic square to help him address questions about how cultural and social

conditions form into ideologies and how these ideologies influence consumers’ thoughts, narratives, and

actions regarding technology. Inf fact, has been discovered that using the semiotic square in the context

of his study allowed him to see relationships between seemingly disparate ideological elements, and to

look how paradoxical ideological elements interact to inform how consumers think about and use

technology. Another pre-existing theoretical perspective that has proven useful for many consumers

researchers comes from the work of Pierre Bourdieu. He provided “thinking tools”-> conceptual terms

which frame his approach to understanding society, and specific practices and fields of practice within

larger societies. Finally, we focus on another concept, the habitus, that is a set of “taken-for-granted

tastes, skills, styles and habits acquired through early socialisation and subsequent education.

In conclusion, there are many other pre-existing theories that have been used by individual researchers

in our field. And often, researchers will use a lot of prior theories to inform their analysis and

interpretation.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Neuman, Lawrence W. - Basics of Social Research - Qualitative - Quantitative Approaches PDFDocument399 pagesNeuman, Lawrence W. - Basics of Social Research - Qualitative - Quantitative Approaches PDFS. M. Yusuf MallickNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- GBS 700 - RESEARCH METHODS Hand OutDocument98 pagesGBS 700 - RESEARCH METHODS Hand OutTamaraBookoo100% (1)

- Difference Between Theory and LawDocument17 pagesDifference Between Theory and Lawmira01No ratings yet

- Sociology A Brief Introduction Canadian Canadian 5th Edition Schaefer Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesSociology A Brief Introduction Canadian Canadian 5th Edition Schaefer Solutions ManualStevenMillersqpe100% (34)

- Scientific Method and AttitudeDocument34 pagesScientific Method and AttitudeJeda LandritoNo ratings yet

- AMethodof Phenomenological InterviewingDocument10 pagesAMethodof Phenomenological InterviewingJose Lester Correa DuriaNo ratings yet

- Unit One: IntroductionDocument24 pagesUnit One: IntroductionWondmageneUrgessaNo ratings yet

- 06 Hypothesis Testing For Two Population Parameter PDFDocument52 pages06 Hypothesis Testing For Two Population Parameter PDFAngela Erish CastroNo ratings yet

- MatthewBThompson Tangen McCarthy EvidenceForExpertiseInFingerprintIdentification AAFS2013 Abstract v03Document1 pageMatthewBThompson Tangen McCarthy EvidenceForExpertiseInFingerprintIdentification AAFS2013 Abstract v03MichelangeloNo ratings yet

- Perception of Students About School ClinicDocument12 pagesPerception of Students About School CliniczyikorjaNo ratings yet

- Meta AnalysisDocument22 pagesMeta AnalysisNuryasni Nuryasni100% (1)

- Exploring The Effects of Shared Leadership On Open Innovation in Vietnamese Manufacturing Enterprises: Examining The Mediating Influence of Strategic Consensus and Team PerformanceDocument17 pagesExploring The Effects of Shared Leadership On Open Innovation in Vietnamese Manufacturing Enterprises: Examining The Mediating Influence of Strategic Consensus and Team Performanceindex PubNo ratings yet

- Emp Moti Zuari CementDocument8 pagesEmp Moti Zuari CementMubeenNo ratings yet

- IEA RD Funds Call3 2023Document7 pagesIEA RD Funds Call3 2023ajeng wahyuniNo ratings yet

- Worksheet-Scientific-Method-Rocket PaperDocument5 pagesWorksheet-Scientific-Method-Rocket PaperMickaella MartirNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis and InterpretationDocument32 pagesData Analysis and InterpretationAbdullah RockNo ratings yet

- Prac ResearchDocument100 pagesPrac ResearchSynta Flux100% (1)

- Module 1 Intro To StatDocument27 pagesModule 1 Intro To StatMa. Lawrene T. BascoNo ratings yet

- BSOC 114 - 2023-24 - EnglishDocument4 pagesBSOC 114 - 2023-24 - Englishreenamary1103No ratings yet

- Module 1 (No Answer Key)Document18 pagesModule 1 (No Answer Key)Yna Foronda89% (9)

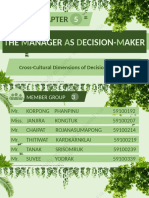

- Week 6 5 The Manager As Decision MakerDocument7 pagesWeek 6 5 The Manager As Decision MakerMari FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Project Guidelines From Mumbai University PDFDocument11 pagesProject Guidelines From Mumbai University PDFzafar mapkarNo ratings yet

- The VariableDocument3 pagesThe VariableYmme LouNo ratings yet

- PBS Band 5 Form 2 Chapter 9Document4 pagesPBS Band 5 Form 2 Chapter 9lccjane8504No ratings yet

- Learning Material - Developing and Using Rubrics - FinalDocument11 pagesLearning Material - Developing and Using Rubrics - FinalLeah Lorenzana Malabanan100% (1)

- Chapter 15 - Audit TheoryDocument45 pagesChapter 15 - Audit TheoryCristel TannaganNo ratings yet

- Unit 6Document18 pagesUnit 6WaseemNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - NHST and Assumptions TestingDocument50 pagesLecture 6 - NHST and Assumptions Testingthivyaashini SellaNo ratings yet

- Module 6 T TestDocument11 pagesModule 6 T TestRushyl Angela FaeldanNo ratings yet

- Scientific MethodDocument5 pagesScientific MethodBianca Charlysse HernandoNo ratings yet