Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Attitudes Towards English in Norway: A Corpus-Based Study of Attitudinal Expressions in Newspaper Discourse

Uploaded by

Hayacinth EvansOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Attitudes Towards English in Norway: A Corpus-Based Study of Attitudinal Expressions in Newspaper Discourse

Uploaded by

Hayacinth EvansCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/286358492

Attitudes towards English in Norway: A corpus-based study of attitudinal

expressions in newspaper discourse

Article in Multilingua · June 2014

DOI: 10.1515/multi-2014-0014

CITATIONS READS

10 792

1 author:

Anne-Line Graedler

14 PUBLICATIONS 47 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

English in Europe View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Anne-Line Graedler on 04 October 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Multilingua 2014; 33(3–4): 291–312

Anne-Line Graedler

Attitudes towards English in Norway:

A corpus-based study of attitudinal

expressions in newspaper discourse

Abstract: This article explores some dimensions of how the role of the English

language in Norway has been discursively constructed in newspapers during

recent years, based on the analysis of data from the five-year period 2008–

2012. The analysis is conducted using a specialised corpus containing 3,743

newspaper articles which were subjected to corpus-based macro-analyses and

techniques, as well as manual micro-level analyses and categorisation. The

main focus of the analysis is on the manifestation of attitudes through various

ways of expression, such as the occurrence of lexical sequences and conceptual

metaphors related to language. The results show that even though positive

perceptions of English were quite frequent in the data, the main part consisted

of expressions where English is seen in a negative light. Hence, a fairly negative

attitude towards the role of English is predominant, as illustrated by the most

frequent conceptual metaphor, language is an invading force, where En-

glish is at war with and seen as representing a threat to the Norwegian lan-

guage.

Keywords: language attitudes, English, Norwegian, newspaper discourse, cor-

pus analysis

DOI 10.1515/multi-2014-0014

1 Introduction

This article explores some dimensions of how the role of the English language

in Norway has been discursively constructed in newspapers during recent

years, using corpus-based methods as a point of departure. The study is based

on the analysis of data from the period 2008–2012, extracted from the media

archive ATEKST (2013). The main focus of the analysis is on the manifestation

Anne-Line Graedler, Hedmark University College, Norway, E-mail: anneline.graedler@hihm.no

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

292 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

of attitudes through various means of expression, such as the occurrence of

lexical sequences and conceptual metaphors related to language.

First, some background information is presented with respect to the situa-

tion of English in Norway today, and the linguistic climate. Then there follows

an account of the data and methods applied in the study. The findings and

results are presented and discussed, and then used as a basis for the identifica-

tion of attitudinal tendencies in the material.

2 Background: English in Norway

Norway has two official languages, Norwegian and Sami, of which Norwegian

is dominant, and the first language of the majority of the population. In addi-

tion to the official languages, Norwegian sign language and several other na-

tional minority languages are recognised in present-day Norway, alongside new

immigrants’ languages. The English language has been present to some extent

since the technical and industrial revolution, when it was used in connection

with maritime life and trade with English-speaking nations. However, until the

mid-20th century only a small part of the population were exposed to and profi-

cient in English. Since World War II exposure to the English language has

steadily increased through various channels such as education, travel and

tourism, television, movies and popular music, magazines and books, and the

Internet.

English was introduced in some schools as early as the 1860s, but did

not become a compulsory subject in the public school system until the 1960s.

Traditionally, it has been considered a foreign language, but the most recent

national curriculum (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training 2006)

implicitly challenges the traditional categories by presenting a new three-way

distinction between the students’ first language, English, and all other foreign

languages. English is now introduced to pupils at a pre-literate stage, and liter-

acy in English develops alongside the development of literacy in the pupils’

first language. Recent surveys rank Norway among the top nations with the

highest English proficiency level (e.g., EF Education 2012), but it does not have

any official status.

From the earliest contact, English loanwords have found their way into the

Norwegian vocabulary. The bulk of loanwords have come after the Second

World War, and several studies have attempted to measure the impact of En-

glish on Norwegian (see Graedler 2012). One of the most recent studies was part

of the inter-Nordic umbrella project Modern import words in the languages in

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 293

the Nordic countries (MIN), and it measured the frequency of English loanwords

in newspaper texts from the year 2000. The Norwegian texts in the project

contained 88 loanwords per 10,000 words of running text (Selback 2007: 61),

a higher frequency than in any of the other Nordic language communities

(Graedler and Kvaran 2010: 34).

Another result of influence is so-called domain loss (Haberland 2005),

where the use of English has become so dominant in certain areas or usage

domains that Norwegian has been said to lose its status, such as in academic

prose (see Soler-Carbonell this issue; Kuteeva and McGrath this issue), pop

music lyrics and lifestyle advertising. At present, this aspect of English influ-

ence is the main concern among Norwegian language policy makers:

Previously the concern was focused on English loanwords. An intermediate form is code-

switching, longer elements of English expressions in Norwegian, typical of youth lan-

guage. These can be omens, but domain loss, a full transition to English within a linguis-

tic domain of usage or function, is what represents the great danger to the Norwegian

language today. (Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs 2008a; my translation)

3 The linguistic climate

Linguistic climate is a concept that frequently occurs in discussions of public

attitudes and political discourse concerning language policy and change in the

Nordic countries (e.g., Venås 1986; Omdal 1999; Thøgersen 2004; Duncker

2009). The concept is usually associated with situational factors related to lan-

guage use and its social position, but often lacks a clear and consistent defini-

tion. As Omdal (1999: 5) points out, deciding which factors are perceived as

most important for the linguistic climate among language users represents a

challenge. In one of the research reports from the MIN project (mentioned

above), the concept is construed as encompassing both language-related and

more general ideological identities related to politics, individualism, etc., and

social factors like gender, income level or place of origin. Further, the linguistic

climate is viewed as a set of “pre-packed opinions” which have crystallised and

which one can be for or against (Kristiansen and Vikør 2006: 214).

In what follows, two interrelated facets of the more general linguistic cli-

mate have been chosen as an interpretative backdrop for the data in the study:

official language policy on the one hand, and linguistic awareness in the popu-

lation on the other.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

294 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

3.1 Official language policy

Language policy is connected to the establishment and maintenance of lan-

guage standards, which may be seen as ideological processes that affect lan-

guage users’ perception of language and normative or prescriptive practices

(Woolard 1998: 21; Milroy and Milroy 1999). This may indirectly affect the way

language users perceive, for instance, English lexical elements in Norwegian.

Features of language contact are often linked with a purist approach to

language. Linguistic purism covers a range of aspects, and with regard to Nor-

wegian, socio-historical changes are considered to have affected the develop-

ment of both formal aspects of the language (morphological and derivational

standards, vocabulary choice, etc.) and language users’ implicit and explicit

assumptions about language in general (Brunstad 2001: 413; Vikør 2010: 20–

23). When the Norwegian language developed into a discrete – standardised –

entity after a long period of Danish rule (1380–1814), it was codified in two

closely related written varieties which received equal official status in 1885,

Bokmål and Nynorsk (see, e.g., Vikør 2001). The Nynorsk community has tradi-

tionally been considered the more purist and less willing to accept words of

foreign origin, since it was based on a nationalist ideology that in principle

excluded any foreign lexical elements (Vikør 2010: 22–23). However, the main

advocate for the precursor of Bokmål in the nineteenth century, Knud Knudsen,

also promoted strong purist views. As mentioned in Section 2, the main focus

of present-day Norwegian language policy in relation to foreign language influ-

ence is expressed through the term domain loss, something that may appear to

be a shift in perspective from a purist ideology to a more knowledge-based

approach to linguistic change (Salö 2013).

Recognition and acceptance of linguistic diversity is another aspect of Nor-

wegian language policy that might affect language attitudes and potentially

generate “enormous societal tolerance for linguistic diversity” in the language

community (Trudgill 2002: 31). No official norm for spoken Norwegian exists,

and local dialects have a high status and are promoted and used in most as-

pects of society. In addition, until recently both of the official written standards

contained a wide variety of optional forms related to orthography and inflec-

tional endings (Language Council of Norway 2012).

3.2 Linguistic awareness

The notion of linguistic climate has also been related to language users’ aware-

ness or consciousness of language (referred to in what follows as linguistic

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 295

awareness) as a result of historical, socio-cultural and sociolinguistic factors.

This form of awareness can cover a wide range of aspects, such as “language

purism, pro-neologism, pro-dialect sentiments, anti-English sentiments, etc.”

(Thøgersen 2004: 24–25). The Norwegian language community has been de-

scribed as linguistically aware partly as a result of the socio-historical develop-

ment of Norwegian. According to Thøgersen, in the Nordic region, language

communities’ linguistic awareness correlates with purism towards English in

the sense that language users who are more aware of their own use of language

and of official language policy also tend to favour their “language of identity”

and avoid foreign influence (cf. Gnutzmann et al this issue). Thøgersen cites

Lund’s (1986: 35) ranking of the Nordic countries according to their linguistic

awareness: the Faroes – Norway – Swedish-Finland – Finland – Sweden –

Denmark (Thøgersen 2004: 25). In this context, Norway tends towards the more

linguistically aware end of the scale, and, as a consequence, is more purist and

less accepting of foreign linguistic influence.

4 Language attitudes

As indicated in the title, this study attempts to disclose underlying attitudes

based on language data from newspapers. Attitudes are commonly defined as

people’s positive or negative opinions or feelings about something and will

here be related to the expression of perceptions of the English language in a

Norwegian linguistic context, and of the role of English in Norwegian language

society.

Attitudes can be both explicit and implicit, as illustrated by two of the sub-

projects in the Nordic MIN project (mentioned above), one of which was a

survey investigation where language users express their attitudes towards En-

glish through an opinion poll (Kristiansen and Vikør 2006), while the other

was a matched-guise test attempting to expose the informants’ subconscious

attitudes (Kristiansen 2006). Interestingly, these two projects produced conflict-

ing results: “Norway and Swedish-speaking Finland change from being the

champions of consciously expressed English-negativity into the most English-

positive of the communities in the subconscious condition” (Kristiansen 2010:

86). This apparent contradiction between implicit and explicit attitudes among

Norwegian language users provides an interesting setting for the present study,

which will supplement the MIN project results with data based on public ex-

pressions related to English.

From a research point of view, newspapers represent an important channel

for linguistic exploration (Crystal 2003: 3; Andersen and Hofland 2012). They

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

296 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

also contribute to making issues of language and language use visible in the

public sphere and are presumed to play a substantial role in the expression

and mediation of a society’s language attitudes (Blommaert and Verschueren

1998; Duncker 2009). Although general views and conceptions are conveyed

by journalists (and editors), Norwegian newspapers are traditionally seen as

mediators of public opinion, in addition to being open to readers’ contributions

in the form of letters to the editor and feature articles. The number of different

Norwegian print media and the rate of readership are both relatively high, and

around 550–600 copies are sold per 1,000 inhabitants (Østbye 2010). Therefore,

a newspaper corpus was chosen as the basis for uncovering attitudes towards

the English language.

5 Methods

In accordance with principles for corpus research as a form of cyclical proce-

dure (Biber 1993; Baker et al. 2008), a pilot project was carried out in order to

identify relevant points of interest and adjust research parameters according to

the practical limitations of the material. A ten-year period (2001–2010) was cho-

sen as the observation period for the pilot study, and after searches based on

various query terms, a limited selection of articles was extracted for more in-

depth analysis of the expression of attitudes. The findings in the pilot study

confirmed that the corpus linguistic approach was an effective method for ex-

tracting relevant data and identifying key lexical expressions and categories

that are used in texts dealing with the topic in question. The study also gave

clear indications that a sifting of the material to create an even more focused

corpus would produce clearer and more relevant results.

5.1 Data collection

The data used in this research are a corpus of newspaper articles collected from

the media archive ATEKST, which at the beginning of 2013 comprised more

than 300 million articles and has a growth of approximately 80,000 articles per

day (Magne Eggen, personal communication, March 8, 2013). The media archive

includes most of the Norwegian newspapers with the largest circulation, and

both national and regional newspapers of different political leanings. However,

very few of the smaller local newspapers have been present in the archive until

recent years. Several previous studies indicate that attitudes towards English

differ somewhat depending upon sociolinguistic factors related to urban/rural

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 297

Table 1: Newspapers included in the study.

Newspaper Circulation 2011 Newspaper type

Aftenposten 235,795 national

VG 211,588

Dagbladet 98,989

Dagens Næringsliv 82,595

Morgenbladet 26,365

Vårt Land 24,448

Klassekampen 15,390

Nationen 12,824

Bergens Tidende 79,467 regional

Adresseavisen 71,657

StavangerAftenblad 63,283

Fædrelandsvennen 36,604

Nordlys 23,627

Romerikes Blad 31,897 local

Byavisa Tønsberg 28,000

Trønder-Avisa 21,975

Agderposten 21,262

Harstad Tidende 11,587

iTromsø 8,304

Altaposten 4,923

Fanaposten 4,681

Brønnøysunds Avis 3,955

Eikerbladet 2,792

Bygdebladet 2,691

life and central/peripheral regions (Ljung 1985; Selback and Kristiansen 2006).

Hence, the wide variety of local newspapers in Norway might represent atti-

tudes and opinions that are less frequently expressed in the larger national

newspapers. The data were therefore drawn from eight national, five regional

and eleven local newspapers published during the five-year period 2008–2012

(Table 1). In contrast, a study of images of English in the French press (Deneire

2012) concludes that “[l]anguage questions are heavily present in the national

press but not in the regional press”, which may reflect the variety in press

culture in different parts of Europe (see, e.g., Elvestad and Blekesaune 2008).

5.2 Compilation of a sub-corpus

While some searches were possible using the ATEKST interface, a sub-corpus

was compiled for further investigation, using specific query terms based on the

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

298 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

Table 2: Size of the sub-corpus.

No. of articles No. of words

National newspapers 2,062 2,732,675

Regional newspapers 1,156 1,289,716

Local newspapers 525 767,560

Total 3,743 4,789,951

results of the pilot study. The compilation of a representative and reliable cor-

pus from a large and varied amount of text requires carefully considered criteria

for text extraction and will in any case result in a “trade-off ... between a corpus

that can be deemed incomplete, and one which contains noise (i.e. irrelevant

texts)” (Gabrielatos 2007: 6).

For the extraction of texts that deal with the role of English in Norway, the

obvious query term is engelsk* (‘English’), which returned 64,831 hits (i.e. arti-

cles) from the newspapers chosen. In the process of narrowing down the mate-

rial, norsk* (‘Norwegian’) was used as another query term, since the relevant

texts tend to deal with the relationship between the two languages. Both en-

gelsk* and norsk*, however, are slightly problematic in this respect since they

function as adjectives merely referring to nationality (and other things, such as

the dog breed English Setter), in addition to adjectival and nominal reference

to the languages. For this reason, the query term språk (‘language’) was added

to increase the relevance. Lastly, a decision was made to remove a batch of

irrelevant texts by excluding 5,458 of the articles containing the word fotball*

(‘football’). The final search string: engelsk* norsk* AND (språk OR sprog) AND-

NOT fotball* resulted in a total of 3,743 articles, with a distribution as shown

in Table 2.

5.3 Data analysis

The first steps of the sub-corpus processing involved macro-analyses and tech-

niques generating linguistic information and lexical patterns in the form of

concordance lists, word frequencies, collocates, clusters and keywords, by the

use of the program WordSmith Tools 6 (Scott 2013). The findings generated by

the corpus tools then underwent manual micro-level analyses and categorisa-

tion based on the content of the text extracts.

Although the extraction of relevant data is carried out using corpus analy-

sis tools, quantitative results have not been given particularly strong emphasis

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 299

in this study. Only some aspects of the multifaceted material are discussed and

analysed, and figures and percentages could easily change on the inclusion of

other aspects in the analysis. However, the attempt at identifying public atti-

tudes in the material makes the consideration of dominant tendencies a key

issue.

6 Findings

The following section presents some of the results from various forms of analy-

ses based on the newspaper corpus. Several aspects of the data have been

chosen for analysis, but special focus is devoted to two aspects, viz. co-textual

patterns and conceptual metaphors. The patterns that co-occur with the core

query term engelsk*, including verb constructions, adjectives, etc., give an indi-

cation of ways in which the English language is represented in the texts. The

metaphorical expressions that are used to describe the languages involved pro-

vide further documentation of underlying attitudes towards the role of English.

Before approaching these two focus areas, some other aspects of the corpus

texts will be discussed.

6.1 Newspaper focus on English during 2008–2012

One of the initial aims of this project was to determine to what extent Norwe-

gian newspapers devote space to the issues of English in Norway and English

influence on Norwegian. Based on previous research on the impact of English

(see Graedler 2012), a possible hypothesis would be that the focus on the En-

glish language in newspapers has increased. A frequency analysis of occurren-

ces of the query term engelsk* in the pilot project suggested that interest in the

topic had been fairly stable during the ten-year period 2001–2010, with some

variations that could be associated with identifiable external criteria such as

the launching of official language policy documents (Language Council of Nor-

way 2005; Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs 2008b). As shown in Figure

1, the number of hits of the query term engelsk* somewhat surprisingly de-

creased during the five-year period 2008–2012, which might indicate that inter-

est in the topic is on the wane.

However, since this probe includes uses of the word in all possible textual

contexts, the results in Figure 1 do not indicate very much about the actual

focus on the role of English during these years.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

300 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

Figure 1: Frequency of the query term engelsk*.

The application of the corpus concordancer (Scott 2013) returned a list of

11,745 occurrences of the query term engelsk*. A manual analysis of the con-

cordance list resulted in the deletion of a large number of occurrences, such as

texts containing descriptions of specific persons or countries, reports about

various aspects of English as a school subject, book and film reviews, articles

about translation and the international book market, about English word forms

and their etymology, etc. Only those occurrences were kept where the textual

context indicated relevant topics, either of the whole or parts of the text in

question. As a result of the removal of irrelevant articles, a specialised corpus

containing 3,014 occurrences remained for analysis.

6.2 Lexical characteristics of the chosen texts

The texts kept for further analysis all deal with some aspect of the role of

English in Norway. In order to detect specific lexical characteristics of these

texts, a keyword analysis was conducted using WordSmith 6. Keyword analyses

compare selected texts with a larger reference corpus and identify lexical items

that occur with a high frequency in the selected texts, compared to the refer-

ence corpus. In this study, the specialised corpus was compared to a reference

corpus consisting of all kinds of newspaper articles, downloaded from the same

source (ATEKST). Table 3 presents the words that occurred in the list of the 100

most frequent keywords from the specialised corpus, after the deletion of the

query terms (English, Norwegian, language) and a number of grammatical func-

tion words.1

As expected, some of the keywords are meta-linguistic terms that enable

the description and discussion of language (Category 1). Although most of them

1 All translations of the lexical data from the Norwegian newspaper corpus are mine.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 301

Table 3: Keyword categories.

1 Meta-linguistic terms word(s), the words, the word, expression, texts, loan-

word(s), dialect, communication, written language

2 Words related to the expression say(s), think (= be of the opinion), continual/

of opinions and attitudes incessant, adequate (of full value), think (= believe)

3 Words related to Norwegian the Language Council, the Language Council’s, the

language policy language policy report, language policy, domain

loss, personal names that reference various

language policy makers

4 Words related to language Nynorsk, the mother tongue, mother tongue, Bokmål,

standards and national identity the Bokmål, Norway (Nynorsk word form), foreign

language, Norwegians, internationalization, foreign,

Latin, German, English (English word form)

5 Words related to usage domains technical language, academia, trade and industry,

artists, teaching language, domain loss, subject(s)

6 Words related to the usage of sing, sings, students, the students, the usage,

English usage, use, uses, speak(s), write, example, teach/

learn, master(s), v.

are general and not very advanced, the specific term loanword indicates a form

of linguistic awareness where the standard national language is perceived as

an immutable structure that may be affected by vocabulary from other lan-

guages. The keywords in Category 2 are more specifically related to the expres-

sion of opinions and attitudes, and include some reporting verbs and qualita-

tive adjectives.

Furthermore, again not surprisingly, a number of the keywords are linked

to language policy documents or authorities (Category 3). Names have a ten-

dency to occur in keyword lists, and this list contains names of Language Coun-

cil directors as well as a minister who oversaw one of the recent national lan-

guage policy reports. The prominence of the term domain loss, like loanword,

may be seen as an indication of linguistic awareness, but is first and foremost

heavily associated with language policy documents, where this is one of the

focus areas (cf. the quote in Section 2).

The significance of the conception of language as a carrier of national iden-

tity is clearly visible in the keyword list. Category 4 contains several terms

denoting varieties of language standards (e.g. Bokmål, German) as well as ex-

pressions related to national identity (e.g. mother tongue, foreign language).

Finally, the keywords in Category 5 are related to usage domains that are

specifically associated with the use of English, which shows that discussions

tend to focus on those specific domains in particular. Category 6 consists of

several verbs and some other words related to the use of the English language:

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

302 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

singing, speaking, writing, mastering another language, or words that are associ-

ated with education (e.g., students, teach/learn). Although the keywords give

an indication of the focus areas in the selected texts, they do not signal any

specific language attitudinal tendencies on behalf of the newspaper writers.

6.3 Perceptions of the English language

In the pilot study, frequent word clusters reflected some information similar to

Category 6 in Table 3, about the usage of English, and a highly frequent two-

word string (... that English ...) indicated that a large part of the texts contained

allegations and claims about the English language. In the specialised corpus

for the main study, however, the ubiquity of the query terms made cluster

analysis more problematic and less informative because of the predominance

of clusters such as Norwegian and English or in English and. For this reason

analyses based on concordance lists were preferred in the pursuit of expres-

sions of language attitude.

The discursive patterns used in connection with engelsk* indicate a number

of underlying perceptions of the role of English. One type of example that may

serve as an illustration of this is the pattern in which the core word is followed

by a verbal construction. This results in statements of the kind displayed in

Table 4. The categories are ranked according to size; however, since not every

occurrence of the pattern displays evidence of perceptions of English, and sev-

eral examples are borderline cases, only an approximate percentage is included

in the table.

As Table 4 shows, the largest category (Category 1) contains statements

where English is described and perceived as an expanding language, often in

the process of taking over important usage domains in Norway, or even in

the entire world. Several of the statements contain predictions about future

developments, and most of these have a negative slant where English is fre-

quently seen as an invading force, for example, English has forced its way in

everywhere. Statements about the increasing use of English in various contexts

tend to be more neutrally expressed, for example, English will become a natural

second working language.

Another large category (Category 2) contains statements that mention spe-

cific usage areas where English is increasing or dominant, such as academia,

finance, the oil industry, culture and net-based communication. The same areas

tend to recur in many of the statements, and the focus is on English as a

language that takes over domains previously covered by Norwegian. Again, the

majority of the statements occur in negatively biased texts. In some cases the

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 303

Table 4: Categories based on the core word engelsk* + a verbal construction.

The role of English Examples

1 as an expanding language English makes itself increasingly assertive

(≈ 23 %) English will become a first language

English pushes its way forward

2 as predominant in various English is young people’s net language

usage domains English is the international medical language these days

(≈ 19 %) English takes over vulnerable domains

3 as superior to Norwegian English is a much richer language than Norwegian

(≈ 16 %) English is more figurative than the Norwegian languages

4 as a world language English has become a universal language

(≈ 12 %) English is our days’ Latin

5 as a dominant language English is the number one language

(≈ 11 %) English is in a unique position

6 as a negative or English is the main threat to the Norwegian language

destructive force (≈ 8 %) English takes over and ruins other languages

7 as a natural language English is a language that feels natural

(≈ 7 %) English is not a problem

8 as an essential resource English will remain important

(≈ 4 %) English is an indispensable means of communication

role of the varieties of Norwegian is perceived as slightly different, as in exam-

ple (1). Here, the description of how English affects the two written standards

in different ways is used as a rationale for the persisting strength and useful-

ness of the minority standard Nynorsk:

(1) ... Bokmål is more exposed to anglicisation than Nynorsk ... The reason

is that English has become a working language primarily in areas that

used to belong to Bokmål, for instance trade and industry. Also, Nynorsk

has not been used much in research. So to all those who thought that

Nynorsk was on its way out: The position of Nynorsk is as strong as it

was thirty years ago, while the use of Bokmål decreases. (Berg 2008)

As shown in Category 4, many of the articles in the material describe English

as a world language, dominant in international communication, or as a lingua

franca on a par with or surpassing the previous role of Latin in academic cir-

cles. Category 5 contains more biased statements that focus on the omnipotence

of English, both globally and with particular focus on Norwegian users, for

example, English has been given an enormous influence on all groups of the

population. Again, the perception of English as a – mainly negative – dominant

force lies at the basis of several of these statements.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

304 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

A number of statements contain more specific descriptions of English as a

negative or destructive force (Category 6). English is characterised using adjec-

tives such as contagious, deceitful, forcible, frightening and undermining, and

personified as an enemy, a scoundrel and a troll. Verbs denoting various aspects

of damage and destruction are applied in these statements, for example, English

inflicts (fear), beats, threatens, takes over and ruins (languages), will destroy

and is about to kill (Norwegian). Several of these statements are undoubtedly

emphatic expressions of attitudes towards the role of English. However, on

closer inspection the more intense style of expression is often found in articles

with opposing or more nuanced attitudes, where word combinations like the

ones mentioned above are disregarded or disparaged, as in example (2):

(2) Many people will assume that the horrible English is the frightening

thing for Norwegian. But English in itself is not the problem ... (Hauglid

2010)

At the other end of the range are expressions that characterise English as an

essential resource in present-day Norway, and as a language that is practical,

obvious and an everyday language for Norwegian language users (Categories 7

and 8). Several of these expressions appear in articles about a new generation

of young fictional writers, and about Norwegian songwriters who write English

lyrics, and who convey a stronger sense of familiarity with English than Norwe-

gian, for example, English is the language I feel most at home with as a song-

writer.

The relatively large Category 3 contains expressions with an even more

positive attitudinal approach towards English as a superior language, especial-

ly in relation to Norwegian. There are more than twice as many statements here

as in the “opposing” category of English as a negative or destructive force

(Category 6). A range of characterising adjectives describe English not just as

generally very good (cool, great, fantastic, fun, interesting), but as qualitatively

superior in many ways (figurative, melodious, precise, rich, softer, sophisticated),

as more up to date (fashionable, hip, in, modern, trendy) and as a handy tool

for communication (easy, simple). Compared to the negative statements of En-

glish as a negative or destructive force, Category 3 lacks personifications of

English as a superior being, but includes some verbs that express the ways in

which English is superior to Norwegian, for example, English functions (better),

enables us (to communicate with more people), sounds (good/better/cooler than

Norwegian), etc. As is the case with the strong negative statements, some of

the positive expressions occur in articles where different attitudes are dis-

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 305

cussed, but most of them appear as direct reflections of the speaker or writer’s

attitude towards English (and Norwegian).

To sum up, the patterns in the material show both negative, positive and

more neutral perceptions of the English language. The largest category of state-

ments (Category 1) refer to English as an expanding force which dominates in

many fields, both related to usage domains and geographical areas. Some of

these statements do not contain particularly negative elements, but the catego-

ry as a whole has a distinct slant towards a negative perception of English,

and, in combination with the more pronounced Category 6, where English is

perceived as a negative and destructive force, count for more than half of the

total. However, a substantial number of statements (around one third) are not

particularly negative, and numerous statements can be placed at the opposite

end of the scale where English is perceived in a very positive way.

6.4 Conceptualization of language through metaphors

Conceptual metaphors are used to describe one conceptual domain in terms of

another conceptual domain (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Kövecses 2002) and pro-

vide another strategy for discovering underlying attitudes in discourse. Political

discourse is often about convincing others by appealing to their emotions,

which may be reflected in the use of conceptual metaphors. Metaphors can also

be used to simplify complex issues, since they tend to emphasise one aspect of

the situation, but may play down or hide others (Duncker 2009).

The material in the present study contains several conceptual metaphors

used to describe languages and relationships between them, as illustrated in

Table 5. Some of the metaphors relate to language in general, whereas others

are used to render concrete the specific nature of only one language (English

or Norwegian).

The anthropomorphic conceptualisation of language (language is a hu-

man being) is one of the fundamental ways of describing languages in the

Western world, and can be traced back to the beginning of recorded history

(Watts 2011: 12–13). In the present data the use of this metaphor contributes

towards clarifying the conflicts between English, which takes the role of an evil

and malignant human being, and Norwegian, which is conceived of as vulnera-

ble and wretched, a victim of various kinds of ill treatment. Another traditional

language metaphor is also from the organic source domain, language is a

plant (cf. Watts 2011: 15). The next metaphor in Table 5, language is a com-

modity, is the prototypical metaphor related to language contact situations,

where language is seen as a product that may be borrowed, imported and ex-

ported.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

306 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

Table 5: Conceptual metaphors.

Conceptual metaphor Examples

language is a human the fight for Norwegian as a living language

being they embrace the Norwegian language

Norwegian is being offended

English is the great scoundrel / has crawled ashore in Norway /

sneaks in through the back door

English words force their way in and strangle Norwegian words

English is about to kill Norwegian

If Norwegian is put in the grave ...

language is a plant [English is] gout weed in the garden. I want to weed it out

Norwegian dialects blossom in the young people’s SMS language

language is a English import words, English loanwords

commodity the most important import harbour for the English language

English has not been the sole exporter to Norwegian

language is water they open all dams for English loanwords

Norwegian is being watered down by English words

English pours in over the country

the Norwegian wave that rolls over the town

language is a fragile the Norwegian language must be reinforced / developed /

construction maintained / taken care of / tended / defended / treasured

language is an to litter our language with English words and expressions

environment tried to pollute our mother tongue

substantial linguistic pollution

language is an to raise barriers against English loanwords

invading force to protect the Norwegian language against English

the Norwegian language warriors

invasion of English into Norwegian

English gains ground in more and more areas, Norwegian loses

ground

Many languages suffer from linguistic occupation.

Norwegian language is a powerless victim

English is a part of a linguistic liberation

English is the main enemy / has forced its way in everywhere /

rules the world

One of the classical elements serves as another source domain in the data:

language is water. While often exemplified by highly frequent expressions

related to language fluency, the water metaphors in the present material are

much more dramatic, and describe language (usually English) as a large wave

or stream flowing in uncontrolled motion, resulting in flooding or even drown-

ing, and requiring damming to protect another language (usually Norwegian),

often conceptualised as pristine or fertile land.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 307

In the continuation of this, several metaphors describe Norwegian as a

fragile construction that needs to be maintained and protected from possible

damage caused by English. A similar metaphor is described by Duncker (2009:

76), language is a building, where language decay is seen as one of the main

results of language contact.

Another way of conceiving of the destruction of language is the metaphor

language is an environment (cf. Duncker 2009). From this point of view

language is seen as a pure ambience (Norwegian) which is polluted, contami-

nated and eventually broken down as a result of influence from another lan-

guage (English). In the 1990s this conceptual domain was exploited by the

Norwegian Language Council which launched the “Campaign for the Environ-

mental Protection of Language”, a metaphor that triggered reactions from sev-

eral linguists (e.g. Hovdhaugen 1990).

The main conceptual domain for metaphorical expressions of the relation-

ship between English and Norwegian is war: language is an invading force.

This metaphor has also been in use for a long time; after the second world war

influence from English received increasing attention in Norway, and during the

1960s, English influence was depicted as a linguistic “invasion” (Hellevik 1963:

9, 15). This relationship is also reflected in the expressions discussed in Section

6.3 above, where the perception of English as a negative or destructive force is

one of the distinct categories. This conceptual domain overlaps with the under-

lying domain language is a human being, since fighting and warfare is basi-

cally carried out by humans.

An interesting deviant example is English is a part of a linguistic liberation,

where the co-text is related to the introduction of English in Norwegian society

after the Second World War. The conclusion, however, clearly indicated by the

examples in Table 5, is that the conceptual metaphors in the newspaper texts

show a strong tendency to see English as a threat to Norwegian.

7 Conclusions

In this article, I have looked at the expression of attitudes towards English in

Norwegian society through examining discursive patterns in newspaper texts

that can be connected to language perception. One of the main inspirations for

this study was the diverging results of a previous investigation of Norwegian

attitudes towards English (the MIN project, see Kristiansen 2010), where explicit

and implicit attitudes appeared to be in conflict. The results of the present

study showed that while the core query term engelsk* occurs in many different

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

308 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

textual contexts, a substantial part of the sub-corpus compiled for the study

did indeed contain occurrences in discourse where the term reflects attitudes

towards the role of English.

In Section 3 the notion of linguistic climate, including official Norwegian

language policy, was introduced as potentially relevant for language users’ atti-

tudes towards English in present-day Norway. A keyword analysis of the sub-

corpus (Table 3) indicated that official language policy documents and state-

ments often set the lexical standard for the way this topic is dealt with in

newspaper articles. Other findings suggest that there may be a disjuncture be-

tween policy and practice, such as the categories in Table 4 where perceptions

of English as a superior language are expressed twice as often as the conflicting

perceptions of English as a negative force. But the main results from the analy-

sis show that a fairly negative attitude toward the role of English is predomi-

nant, which can be said to concur with both the main trend in official language

policy documents, and with the classification of Norwegian language users as

linguistically aware and therefore engaged in “protecting” their own language.

The most frequent conceptual metaphor in the material is language is an

invading force, where English is at war with Norwegian, and seen as repre-

senting a threat to the Norwegian language.

While the point of departure for the analysis is lexical items with explicit

subject-related content, the data may also be said to reflect some general ideo-

logical trends from a more overarching perspective. There are various manifes-

tations of attitudes that reflect linguistic conservatism and purism. One is the

perception of English as a destructive force that breaks down the Norwegian

language by causing (basically) lexical damage. Another is the metaphorical

discourse where English is seen as contaminating the pure Norwegian language

in various ways, both lexically and structurally, but also with respect to loss of

entire usage domains to English. Linguistic purism is inherently related to a

nationalist ideology, and foreign language sources are often perceived as a

social or political threat, in addition to the linguistic danger. Keeping the lan-

guage free of foreign elements may be seen as a way of maintaining and sup-

porting national identity.

The data do not contain much concrete evidence of English influence being

seen as a pluralistic phenomenon. Although most Norwegians see their country

as an egalitarian society with small social inequalities, even compared to other

Scandinavian countries, this does not seem to affect linguistic attitudes towards

English. However, there are many examples of positive attitudes towards En-

glish where it is perceived as a positive or superior linguistic resource. Here,

the underlying ideology of the discourse can be seen as related to English as a

world language with prestigious value. In this global perspective Norwegian

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 309

may be regarded as a small minority language located on the geographical

margin, on a par with vernacular languages with no communicative value out-

side the tribe.

While several different but interrelated ideological trends are detectable in

the data, the main trend is language endangerment, which is manifested as

concerns that Norwegian is being undermined or is on its way to becoming

extinct (see also Linn 2010). This ideological trend also to some extent perme-

ates the main aim of contemporary language policy, which is to secure the

position of Norwegian as a fully adequate means of communication in Norwe-

gian society (Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs 2008b). This policy state-

ment is connected both to the role of Norwegian in an increasingly globalised

world, and to the role that the English language plays in Norway as a result of

globalisation. As confirmed in the quote in Section 2, lexical borrowing in itself

was previously seen as a potential threat to the language from a language

political perspective. The concern that loanwords may affect the future of Nor-

wegian is still evident in some fairly recent official documents, where the in-

crease in the volume of loanwords is regarded as a warning sign of a potentially

negative development (e.g., Ministry of Labour and Government Administration

2003: 46; Language Council of Norway 2005: 14; Ministry of Culture and Church

Affairs 2008b: 94).

This study is by no means complete or conclusive, and opens up several

other approaches and research avenues within the same problem area and

based on the same data. Some further research is planned in order to uncover

potential variations in the source material, such as a comparison of attitudes

as expressed in different newspaper genres, specifically editorial versus inde-

pendent texts, including letters to the editor, which represent writers with dif-

ferent roles and objectives. Another approach would be a comparison of discur-

sive constructions among different newspaper types. The interest here could

potentially lie in the political affiliations of the newspapers, but may also be

related to the variation between national, regional and local newspapers.

An interesting question that has not been considered in this paper is wheth-

er there are differences between the attitudes expressed by users of the two

written standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk. The historical and sociolinguistic back-

ground of the two standards is somewhat different, and, as mentioned in Sec-

tion 3.1, Nynorsk tends to be associated with a more purist view of language.

The ideological focus may also be linked to the role of Nynorsk as a minority

standard with strong links to regional dialects and formal characteristics associ-

ated with specifically rural traditional forms.

Lastly, since this study is restricted to newspapers published in the written

format, a new large-scale search for the media expression of attitudes and lan-

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

310 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

guage ideology should include other forms such as audio-visual and net-based

media.

References

Andersen, Gisle & Knut Hofland. 2012. Building a large corpus based on newspapers from

the web. In Gisle Andersen (ed.), Exploring newspaper language: Using the web to

create and investigate a large corpus of modern Norwegian, 1–28. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

ATEKST. 2013. Retriever A/S. www.retriever.no (accessed 5 February 2013).

Baker, Paul, Costas Gabrielatos, Majid Khosravinik, Michał Krzyżanowski, Tony McEnery &

Ruth Wodak. 2008. A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse

analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers

in the UK press. Discourse and Society 19(3). 273–306.

Berg, Thomas. 2008. Kan norsk overleve? Det skal Trond Giske avgjøre før sommerferien

[Can Norwegian survive? Trond Giske will decide this before the summer vacation].

Morgenbladet, 18. April, p. 30.

Biber, Douglas. 1993. Representativeness in corpus design. Literary and Linguistic

Computing 8(4). 243–257.

Blommaert, Jan & Jef Verschueren. 1998. The role of language in European nationalist

ideologies. In Bambi B. Schieffelin, Kathryn A. Woolard & Paul V. Kroskrity (eds.),

Language ideologies: Practice and theory, 189–201. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brunstad, Endre. 2001. Det reine språket. Om purisme på dansk, svensk, færøysk og norsk

[The pure language. On purism in Danish, Swedish, Faroese and Norwegian]. Bergen:

University of Bergen PhD dissertation.

Crystal, David. 2003. English as a global Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Deneire, Marc. 2012. Images of English in the French press. Conference presentation,

English in Europe: Debates and discourses, University of Sheffield.

www.englishineurope.postgrad.shef.ac.uk/resources/PRESENTATIONS/Images_of_

English_-DENEIRE.pdf (accessed 20 October 2012).

Duncker, Dorthe. 2009. Kan man tage temperaturen på et sprogligt klima? Nogle

sprogpolitiske tendenser i danske avismedier 1990–2007 [Can one measure the

temperature of a linguistic climate? Some language political tendencies in Danish

newspaper media]. Språk i Norden 2009. 71–84.

EF Education. 2012. EPI English Proficiency Index. EF Education First Ltd. www.ef.co.uk/epi/

(accessed 21 February 2013).

Elvestad, Eiri & Arild Blekesaune. 2008. Newspaper readers in Europe. A multilevel study of

individual and national differences. European Journal of Communication 23(4).

425–447.

Freake, Rachelle. 2012. A cross-linguistic corpus-assisted discourse study of language

ideologies in Canadian newspapers. Proceedings of the 2011 Corpus Linguistics

Conference, Birmingham University. www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-

artslaw/corpus/conference-archives/2011/Paper-17.pdf (accessed 6 October 2012).

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

DE GRUYTER MOUTON Attitudes towards English in Norway 311

Gabrielatos, Costas. 2007. Selecting query terms to build a specialized corpus from a

restricted-access database. ICAME Journal 31, 5-43.

Graedler, Anne-Line. 2012. The collection of anglicisms: Methodological issues in connection

with impact studies in Norway. In Cristiano Furiassi, Virginia Pulcini & Félix Rodríguez

González (eds.), The anglicization of European lexis, 91–109. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Graedler, Anne-Line & Guðrun Kvaran. 2010. Foreign influence on the written language in

the Nordic language communities. International Journal of the Sociology of Language

204. 31–42.

Haberland, Hartmut. 2005. Domains and domain loss. In Bent Preisler, Anne Fabricius,

Hartmut Haberland, Susanne Kjærbeck & Karen Risager (eds.), The consequences of

mobility: Linguistic and sociocultural contact zones, 227–237. Roskilde: Roskilde

University.

Hauglid, Espen. 2010. Tatt på ordet [Taken at their word]. Dagens Næringsliv, morning issue,

19. October, p. 58.

Hellevik, Alf. 1963. Lånord-problemet. To foredrag i norsk språknemnd [The loanword

problem. Two lectures at the Norwegian language board], (Norsk språknemnd

småskrifter 2). Oslo: Cappelen.

Hovdhaugen, Even. 1990. Lånord og myter [Loanwords and myths]. Språknytt 3. 5–6.

Kristiansen, Tore. 2010. Conscious and subconscious attitudes towards English influence in

the Nordic countries: Evidence for two levels of language ideology. International Journal

of the Sociology of Language 204. 59–95.

Kristiansen, Tore & Lars S. Vikør (eds.). 2006. Nordiske språkhaldningar. Ei meiningsmåling

[Nordic language attitudes: An opinion survey]. Oslo: Novus forlag.

Kristiansen, Tore (ed.). 2006. Nordiske sprogholdninger. En masketest [Nordic language

attitudes: A matched guise test]. Oslo: Novus forlag.

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2002. Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Language Council of Norway. 2005. Norsk i hundre! Norsk som nasjonalspråk i

globaliseringens tidsalder. Et forslag til strategi [One hundred years of Norwegian in

motion! Norwegian as a national language in the era of globalization: A strategy

proposal]. www.sprakrad.no/upload/9832/norsk_i_hundre.pdf (accessed 18 March

2013).

Language Council of Norway. 2012. Rettskrivning og ordlister [Orthography and glossaries].

www.sprakradet. no/Sprakhjelp/Rettskrivning_Ordboeker/ (accessed 6 March 2013).

Linn, Andrew R. 2010. Can parallelingualism save Norwegian from extinction? Multilingua

29(3/4). 289–305.

Ljung, Magnus. 1985. Lam anka – ett måste? En undersökning av engelskan i svenskan,

dess mottagande och spridning [Lame duck – a must? An investigation of English in

Swedish, its reception and spread]. EIS Report No. 8. Stockholm: University of

Stockholm.

Lund, Jørn. 1986. Det sprogsociologiske klima i de nordiske lande [The language-

sociological climate in the Nordic countries]. Språk i Norden 1986, 34–45.

Milroy, James & Lesley Milroy. 1999. Authority in language: Investigating Standard English,

3rd edn. London: Routledge.

Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs. 2008a. Mål og meining. Ein heilskapleg norsk

språkpolitikk, kortversjon [Language and meaning/language with a purpose. A

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

312 Anne-Line Graedler DE GRUYTER MOUTON

comprehensive Norwegian language policy. Short version]. www.regjeringen.no/upload/

KKD/Kultur/Sprakmelding_ kortversjon_feb2009.pdf (accessed 18 March 2013).

Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs. 2008b. Mål og meining. Ein heilskapleg norsk

språkpolitikk [Language and meaning/language with a purpose. A comprehensive

Norwegian language policy]. Report to the Storting No. 35, 2007–2008.

www.regjeringen.no/pages/2090873/PDFS/STM200720080035000DDDPDFS.pdf

(accessed 18 March 2013).

Ministry of Labour and Government Administration. 2003. Makt og demokrati. Sluttrapport

fra Makt- og demokratiutredningen [Power and democracy. End report from the Power

and democracy project], Official Norwegian Report (NOU) 2003:19. www.regjeringen.no/

Rpub/NOU/20032003/019/PDFS/NOU200320030019000DDDPDFS.pdf (accessed 25

May 2012).

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2006. The knowledge promotion. National

curriculum for knowledge promotion in primary and secondary education and training.

www.udir.no/Stottemeny/English/Curriculum-in-English/_english/Knowledge-

promotion---Kunnskapsloftet/ (accessed 18 March 2013).

Omdal, Helge. 1999. Språklig mangfold og språklig toleranse [Language variation and

language tolerance]. Språknytt 3/4, 4–11.

Østbye, Helge. 2010. Media landscape: Norway. Medianorway. www.ejc.net/media_

landscape/article/norway/ (accessed 15 October 2012).

Salö, Linus. 2013. Crossing discourses: Language ideology and shifting representations in

Sweden’s field of language planning. www.tilburguniversity.edu/upload/f0958fd4-cfb7-

4602-b5c4-2a4cc9e7cfc7_TPCS_61_Salo.pdf (accessed 26 August 2013).

Scott, Mike. 2013. WordSmith Tools version 6. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software.

Selback, Bente. 2007. Norsk [Norwegian]. In Bente Selback & Helge Sandøy (eds). 2007. Fire

dagar i nordiske aviser. Ei jamføring av påverknaden i ordforrådet i sju språksamfunn

[Four days in Nordic newspapers. A comparison of influence in the lexicon of seven

language communities], 49–66. Oslo: Novus.

Selback, Bente & Tore Kristiansen. 2006. Noreg [Norway]. In Tore Kristiansen (ed.), Nordiske

sprogholdninger. En masketest [Nordic language attitudes: A matched guise test],

65–82. Oslo: Novus.

Thøgersen, Jacob. 2004. Attitudes towards the English influx in the Nordic countries:

A quantitative investigation. Nordic Journal of English Studies 3(2). 23–38.

Trudgill, Peter. 2002. Sociolinguistic variation and change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press.

Venås, Kjell. 1986. Tankar om det språksosiologiske klimaet i Norden [Reflections on the

language-sociological climate in the Nordic countries]. Språk i Norden 1986. 6–24.

Vikør, Lars Sigurdsson. 2001. The Nordic languages: Their status and interrelations. Oslo:

Novus.

Vikør, Lars Sigurdsson. 2010. Language purism in the Nordic countries. International Journal

of the Sociology of Language 204. 9–30.

Watts, Richard J. 2011. Language myths and the history of English. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Woolard, Kathryn A. 1998. Introduction: Language ideology as a field of inquiry. In Bambi B.

Schieffelin, Kathryn A. Woolard & Paul V. Kroskrity (eds.), Language ideologies: Practice

and theory, 3–47. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brought to you by | Hoegskolen i Hedmark

Authenticated | anneline.graedler@hihm.no author's copy

Download Date | 6/2/14 2:10 PM

View publication stats

You might also like

- English in The CommunityDocument13 pagesEnglish in The Communityharold castle100% (1)

- ICS253 161 1 Foundations Logic Proofs S 1 1 1 4 PIDocument75 pagesICS253 161 1 Foundations Logic Proofs S 1 1 1 4 PIDawod SalmanNo ratings yet

- What Is EnglishDocument17 pagesWhat Is EnglishKeerthikaa ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Rindal 2019 PHD Revisited Meaning in English1Document21 pagesRindal 2019 PHD Revisited Meaning in English1Maria Imaculata AmlokiNo ratings yet

- The Influence of English On The Languages in The Nordic CountriesDocument4 pagesThe Influence of English On The Languages in The Nordic CountriesCarlos WagnerNo ratings yet

- Vatty 2017 Learning English in Norway PreprintDocument5 pagesVatty 2017 Learning English in Norway PreprintAna Marie MestosamenteNo ratings yet

- Secondary School Students Perceptions of Language-Learning Experiences From Participation in Short Erasmus Mobilities With Non-Native Speakers of enDocument13 pagesSecondary School Students Perceptions of Language-Learning Experiences From Participation in Short Erasmus Mobilities With Non-Native Speakers of endanil10102018No ratings yet

- Global Englishes and Language Teaching A Review of Pedagogical ResearchDocument33 pagesGlobal Englishes and Language Teaching A Review of Pedagogical ResearchNga ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Iversen 2019cDocument18 pagesIversen 2019cmrsamodien123No ratings yet

- Hultgren 2016 Domain Loss Pre PrintDocument9 pagesHultgren 2016 Domain Loss Pre PrintDaria ProtopopescuNo ratings yet

- Llurda 2004 Non-Native Langauge Teachers and English As An International LanguageDocument11 pagesLlurda 2004 Non-Native Langauge Teachers and English As An International Languagegabar.coalNo ratings yet

- English As A Global Lingua Franca: Changing Language in Changing Global AcademiaDocument19 pagesEnglish As A Global Lingua Franca: Changing Language in Changing Global Academiajonathan robregadoNo ratings yet

- Reading 1Document23 pagesReading 1Kelly Zamira Durán PiñaNo ratings yet

- Lta 54 2Document141 pagesLta 54 2DrGeePeeNo ratings yet

- What Is Applied Linguistics and Its Areas?Document4 pagesWhat Is Applied Linguistics and Its Areas?Muhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- New Gaelic Speakers, New Gaels? Ideologies and Ethnolinguistic Continuity in Contemporary ScotlandDocument22 pagesNew Gaelic Speakers, New Gaels? Ideologies and Ethnolinguistic Continuity in Contemporary ScotlandNikoleNo ratings yet

- Eco Ling ArticleDocument13 pagesEco Ling ArticleAyesha Malik 1520-FSS/BSPSY/F20No ratings yet

- Young Language Learner (YLL) Research:: Ion Drew Angela HasselgreenDocument18 pagesYoung Language Learner (YLL) Research:: Ion Drew Angela Hasselgreennataly ceaNo ratings yet

- Language Policy in DenmarkDocument11 pagesLanguage Policy in DenmarkGALE GWEN JAVIERNo ratings yet

- Kristiansen and Sandoy, 1093, The Linguistic Consequences, IJSL 204Document7 pagesKristiansen and Sandoy, 1093, The Linguistic Consequences, IJSL 204Vamshi Krishna AllamuneniNo ratings yet

- Social Factors and Non-Native Attitudes Towards Varieties of Spoken English: A Japanese Case StudyDocument27 pagesSocial Factors and Non-Native Attitudes Towards Varieties of Spoken English: A Japanese Case StudyDale Joseph KiehlNo ratings yet

- Book The Consequences of Mobility Linguistic and Sociocultural Contact ZonesDocument289 pagesBook The Consequences of Mobility Linguistic and Sociocultural Contact ZonesQuentin Emmanuel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Englishisation' of Education Lanvers and Hultgren - 2018forewordDocument12 pagesEnglishisation' of Education Lanvers and Hultgren - 2018forewordMaría de los Ángeles Velilla SánchezNo ratings yet

- SPGSC Papere 170914Document8 pagesSPGSC Papere 170914Birdlinguist RHNo ratings yet

- Lamos, 6 MYKLEVOLDDocument16 pagesLamos, 6 MYKLEVOLD許智涵No ratings yet

- English As An International Language: Challenges and PossibilitiesDocument17 pagesEnglish As An International Language: Challenges and PossibilitiesLaura TudelaNo ratings yet

- John E. Joseph Language and Politics Edinburgh Textbooks in Applied Linguistics 2007 PDFDocument181 pagesJohn E. Joseph Language and Politics Edinburgh Textbooks in Applied Linguistics 2007 PDFUlwiee AgustinNo ratings yet

- SALÖ, L. (2015) The Linguistic Sense of Placement.Document25 pagesSALÖ, L. (2015) The Linguistic Sense of Placement.Celso juniorNo ratings yet

- Ej 1293060Document9 pagesEj 1293060kinzasaherNo ratings yet

- World Englishes ThesisDocument5 pagesWorld Englishes Thesisbsk89ztx100% (2)

- ELF eelt0667TESOLDocument14 pagesELF eelt0667TESOLPrzemek AmbroziakNo ratings yet

- Research MatrixDocument2 pagesResearch MatrixGALE GWEN JAVIERNo ratings yet

- Language Textbooks Windows To The WorldDocument15 pagesLanguage Textbooks Windows To The WorldMasoumeh RassouliNo ratings yet

- Teaching English Through Pedagogical Translanguaging by Jason Cenoz and Durk GorterDocument12 pagesTeaching English Through Pedagogical Translanguaging by Jason Cenoz and Durk GorterAngel AguirreNo ratings yet

- Teaching English Through Pedagogical TranslanguagingDocument12 pagesTeaching English Through Pedagogical TranslanguagingLaura de los SantosNo ratings yet

- +english Influence On The Scandinavian LanguagesDocument18 pages+english Influence On The Scandinavian Languagesmerve sultan vuralNo ratings yet

- Spain LlurdaMancho-Bars2021 - WorldEnglishesPedagogiesDocument17 pagesSpain LlurdaMancho-Bars2021 - WorldEnglishesPedagogiesRASHAALHANAFYNo ratings yet

- Non-Native-Speaker Teachers and English As An International LanguageDocument10 pagesNon-Native-Speaker Teachers and English As An International LanguageHeidar EbrahimiNo ratings yet

- Johansson Kokkinakis Et Al 2012Document7 pagesJohansson Kokkinakis Et Al 2012minhhieu doanNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Content and Language Integrated LeaDocument26 pagesThe Effects of Content and Language Integrated LeaPaola Minutti ZanattaNo ratings yet

- Aiyre, J. 2012"I Don't Teach Language" The Linguistic Attitudes of Physics Lecturers in SwedenDocument17 pagesAiyre, J. 2012"I Don't Teach Language" The Linguistic Attitudes of Physics Lecturers in SwedenChristian XavierNo ratings yet

- Ecolinguistic Approach To Foreign Language Teaching On The Example of EnglishDocument12 pagesEcolinguistic Approach To Foreign Language Teaching On The Example of EnglishLộcNguyênTrầnNo ratings yet

- Own-Language Use in Language Teaching and LearningDocument38 pagesOwn-Language Use in Language Teaching and LearningAndriana Hamivka100% (2)

- PronunciationDocument31 pagesPronunciationduyentranNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877042814043213 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1877042814043213 MainarapniggNo ratings yet

- Swainston Kasstan 2023Document16 pagesSwainston Kasstan 2023Нурхан ИбрямовNo ratings yet

- E.S.P. As An Academic SubjectDocument9 pagesE.S.P. As An Academic SubjectKirti Bhushan KapilNo ratings yet

- Els 34Document5 pagesEls 34Adam Lawrence TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Cross-Language Effects in Bilingual Production and Comprehension Some Novel FindingsDocument4 pagesCross-Language Effects in Bilingual Production and Comprehension Some Novel FindingsPaula Manalo-SuliguinNo ratings yet

- Optional Courses HT11 Ver AugDocument10 pagesOptional Courses HT11 Ver AugAnnah OkothNo ratings yet

- What Is Applied LinguisticsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Applied Linguisticsmehdimajt100% (1)

- 32 Bfe 50 Cae 599 Be 722Document29 pages32 Bfe 50 Cae 599 Be 722DNo ratings yet

- Smit Dafouz IntroDocument26 pagesSmit Dafouz IntroKristina MacionienėNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 and 4Document8 pagesUnit 7 and 4aminulislamjoy365No ratings yet

- Airey, J. & Cedric Linder 2008 Bilingual Scientific Literacy The Use of English Inswedish University Science CoursesDocument18 pagesAirey, J. & Cedric Linder 2008 Bilingual Scientific Literacy The Use of English Inswedish University Science CoursesChristian XavierNo ratings yet

- Blommaert 2012 Sociolinguistics English Language StudiesDocument18 pagesBlommaert 2012 Sociolinguistics English Language Studiestinlamtsang1004No ratings yet

- Critical Perspective On Language Teaching MaterialsDocument188 pagesCritical Perspective On Language Teaching MaterialsLudmila AndreuNo ratings yet

- 12 - Translingual Entanglements - PENNYCOOK - 2020Document14 pages12 - Translingual Entanglements - PENNYCOOK - 2020Sílvia MônicaNo ratings yet

- Language Teaching 2023 Issue1Document165 pagesLanguage Teaching 2023 Issue1J MrNo ratings yet

- A Sociolinguistically Based Empirically ResearchedDocument22 pagesA Sociolinguistically Based Empirically ResearchedRodrigo DurbahnNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Researches On Nominalization by Linguistics SchoolsDocument11 pagesAn Analysis of Researches On Nominalization by Linguistics SchoolsHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Grammatical Metaphor in SFL A HistoriogrDocument34 pagesGrammatical Metaphor in SFL A HistoriogrHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- IJALEL Vol 5 No 5 2016Document272 pagesIJALEL Vol 5 No 5 2016Hayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Language Sciences: Bernd Heine, Gunther KaltenböckDocument16 pagesLanguage Sciences: Bernd Heine, Gunther KaltenböckHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Language Sciences: Ludger Van Dijk, Erik RietveldDocument14 pagesLanguage Sciences: Ludger Van Dijk, Erik RietveldHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Thesis Movie Transitivity AnalysisDocument47 pagesThesis Movie Transitivity AnalysisHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Postcolonial Feminism and Pakistani Fiction: An Appraisal of The Aesthetic Dimension To The African Philosophy of ClothDocument20 pagesPostcolonial Feminism and Pakistani Fiction: An Appraisal of The Aesthetic Dimension To The African Philosophy of ClothHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Thoughts To PonderDocument13 pagesThoughts To PonderHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Indeterminacy in Process Type ClassificaDocument19 pagesIndeterminacy in Process Type ClassificaHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Bapsi Sidhwa S An American Brat Becoming American But Not YetDocument15 pagesBapsi Sidhwa S An American Brat Becoming American But Not YetHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- The Heart Stomach and Backbone of Pakistan Lahore in Novels by Bapsi Sidhwa and Mohsin HamidDocument20 pagesThe Heart Stomach and Backbone of Pakistan Lahore in Novels by Bapsi Sidhwa and Mohsin HamidHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis BapsiDocument5 pagesData Analysis BapsiHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- A Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis of Qaisra Shahraz's The HolyDocument8 pagesA Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis of Qaisra Shahraz's The HolyHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of English Language and Literature: EmailDocument4 pagesResearch Journal of English Language and Literature: EmailHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- A Study of An American Brat Through SelfDocument25 pagesA Study of An American Brat Through SelfHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- ArtsDocument2 pagesArtsHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Lahiri On DiasporaDocument568 pagesLahiri On DiasporaHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Construal of Identity - JGSI 2021Document20 pagesConstrual of Identity - JGSI 2021Hayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Vocalizing The Concerns of South Asian WomenDocument15 pagesVocalizing The Concerns of South Asian WomenHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Politicising Feminist Discourse LazarusDocument2 pagesPoliticising Feminist Discourse LazarusHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Motivation in English As A Foreign LanguageDocument32 pagesMotivation in English As A Foreign LanguageHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- Communicative Styles, Rapport, and Student Engagement: An Online Peer Mentoring SchemeDocument31 pagesCommunicative Styles, Rapport, and Student Engagement: An Online Peer Mentoring SchemeHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- APA Literature ReviewDocument2 pagesAPA Literature ReviewHayacinth EvansNo ratings yet

- DIP Lab Manual No 01Document20 pagesDIP Lab Manual No 01myfirstNo ratings yet

- Kierkegaard (Concept of History)Document22 pagesKierkegaard (Concept of History)bliriusNo ratings yet

- Am Is Are Has Have 8030Document2 pagesAm Is Are Has Have 8030Daniela Andrea DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Pancha Ratra AgmamDocument5 pagesPancha Ratra AgmamRishikhantNo ratings yet

- Mahayana BuddhismDocument14 pagesMahayana Buddhismelie lucidoNo ratings yet

- Developing ParagraphDocument38 pagesDeveloping ParagraphNavnie0% (1)

- Burgundian LanguageDocument7 pagesBurgundian Languagetolib choriyevNo ratings yet

- BRD Reference 2.3.1Document10 pagesBRD Reference 2.3.1Mminu CharaniaNo ratings yet

- Poets' Choice Is Proud To Announce The Publication of PANDEMIE, New and Selected Poems by Richard Harteis With Dutch Translations and New Art by Tom VeysDocument2 pagesPoets' Choice Is Proud To Announce The Publication of PANDEMIE, New and Selected Poems by Richard Harteis With Dutch Translations and New Art by Tom VeysPR.comNo ratings yet

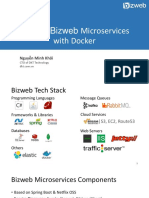

- Building Bizweb Microservices with Docker: Nguyễn Minh KhôiDocument25 pagesBuilding Bizweb Microservices with Docker: Nguyễn Minh KhôinguoinhenvnNo ratings yet