0% found this document useful (0 votes)

113 views9 pagesCIR Vs Next Mobile

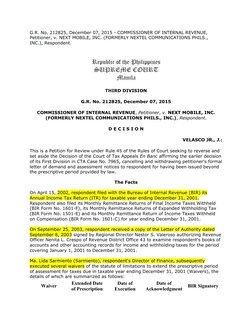

The document discusses a petition by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue seeking to reverse a decision by the Court of Tax Appeals that cancelled tax assessments against Next Mobile, Inc. for being issued beyond the three-year statute of limitations; the Court of Tax Appeals affirmed the cancellation, finding that waivers signed to extend the limitations period were invalid and that there was no evidence of fraudulent tax filings.

Uploaded by

Joshua Erik MadriaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

113 views9 pagesCIR Vs Next Mobile

The document discusses a petition by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue seeking to reverse a decision by the Court of Tax Appeals that cancelled tax assessments against Next Mobile, Inc. for being issued beyond the three-year statute of limitations; the Court of Tax Appeals affirmed the cancellation, finding that waivers signed to extend the limitations period were invalid and that there was no evidence of fraudulent tax filings.

Uploaded by

Joshua Erik MadriaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

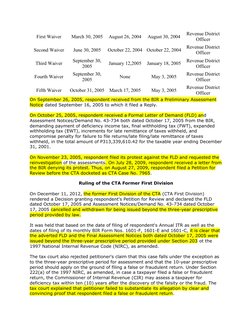

- Case Overview and Background: Discusses the case background, summarizing the key events and actions taken regarding BIR and tax waivers.

- Points of Contention: Details the issues in the case including the validity of waivers and procedural errors.

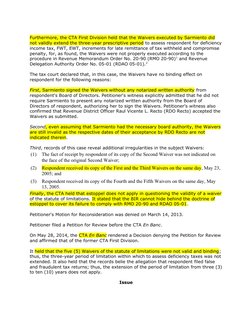

- Our Ruling: Presents the Supreme Court's ruling on the validity of waivers and outlines the legal reasoning.

- Case Analysis and Fault Allocation: Analyzes fault and discusses the implications and liabilities, attributing responsibilities to parties involved.

- Conclusion and Order: Concludes the case with the final decision and orders granted by the Court.