Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Location Choice in Minority Group Suburbanization: The Case of Metropolitan Chicago

Uploaded by

aurennosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Location Choice in Minority Group Suburbanization: The Case of Metropolitan Chicago

Uploaded by

aurennosCopyright:

Available Formats

May 2019

Research Article

Location Choice in Minority Group Suburbanization: The Case of

Metropolitan Chicago

John F. McDonald*

University of Illinois at Chicago Emeritus

And Temple University

Abstract

This paper is a study of suburbanization of African-Americans and Hispanics in

metropolitan Chicago. There are at least three different types of suburbs; satellite cities

with their own employment bases, spillover suburbs adjacent to the central city, and

newer commuter suburbs attractive to middle-class households. The study includes data

on five satellite cities and 109 spillover and other of suburbs in Cook, DuPage, Kane,

Lake, McHenry, and Will Counties in metropolitan Chicago. African-American

suburbanization was concentrated in spillover suburbs and the suburbs of southern Cook

County – locations that already had substantial African-American populations. However,

nearly all of the suburbs had an increase in African-American population. The

suburbanization of Hispanics reflects the much larger growth of this group. From 1990

to 2010 the satellite cities and the suburbs generally more than doubled in their

percentages of Hispanic population. Suburbs with lower income levels in 1990 tended to

attract more Hispanics.

Keywords: Minority groups, Suburbanization, Metropolitan Chicago

*John F. McDonald is Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Illinois at

Chicago, Gerald W. Fogelson Distinguished Chair in Real Estate Emeritus, Roosevelt

University, and Adjunct Professor of Economics, Temple University. Address is 1512

Spruce St., Philadelphia, PA 19102. Email: mcdonald@uic.edu. The author thanks the

editor for his assistance and the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

1. Minority Group Suburbanization

Almost fifty years ago Anthony Downs (1973) argued that America should be “opening

up the suburbs” of the major metropolitan areas. It so happens that the suburbs have been

opened up to a considerable degree, but not in the manner Downs advocated. His idea

was to enable minority groups (mainly African Americans at that time) to move to

suburbs – where employment growth was and is taking place – and to do so while

avoiding leaving behind increasingly impoverished neighborhoods in the inner city. A

sizable body of research, including a study of metro Chicago by McDonald (2018),

shows that suburbanization of minority groups did mean that several inner-city

neighborhoods were left behind with high (over 40%) poverty rates. The growth of

minority populations in the suburbs in recent decades is attracting a great deal of

attention.

The purpose of this paper is to add to research on the topic by dividing suburbs into three

categories; older satellite cities, spillover suburbs adjacent to the central city, and newer

commuter suburbs. The paper concentrates on these types of suburbs to determine which

characteristics are related to increases in the African-American and Hispanic populations.

The focus is on the nature of the suburbs, and not so much on the characteristics of the

minority populations that moved in. A large sociological literature exists on minority

communities in the suburbs – whether they are segmented from or assimilated into the

majority population, whether certain suburbs become minority enclaves, and whether

some suburbs are “melting pots.” This study touches on some of these topics in that

some Chicago suburbs clearly are minority enclaves, while many others contain only

small numbers of African-Americans and Hispanics that suggest some form of

assimilation.

The small group of studies cited here is intended to be a fair representation of the recent

research on the topic. William H. Frey is a leading researcher of this topic, and his report

for 1990 to 2010 (2011) shows that, for the 100 largest metropolitan areas, in 2010 a

majority of African-American, Hispanic, and Asian residents live in the suburbs outside

the primary city. The share of Hispanics living in the suburbs increased from 47% to

59% from 1990 to 2010; the increase for Asians was 54% to 62%, and for African

Americans the increase was from 37% in 1990 to 51% in 2010. Frey’s tabulations

include an adjustment for the fact that some metro areas have more than one “primary”

city (e.g., the primary cities for Washington, DC include Washington DC, Arlington, VA,

and Alexandria, VA).

Douglas Massey is a leader among researchers who study the trends in segregation in

central cities and suburbs. A recent study by Massey and Tannen (2018) finds that levels

of segregation are lower in the suburbs than in central cities, but the segregation of

African Americans, while declining, remains high in both types of locations. Hispanics

have been able to use economic advancement to enter suburbs with low levels of

segregation, but such has not generally been true for African Americans.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Researchers have sought to identify the reasons for this sizable shift of minority

populations to the suburbs. The basic finding is that suburbanization patterns are quite

different for poor minorities compared to middle-class minorities. Johnson (2014)

identifies three types of majority African-American suburbs; decaying, spillover suburbs

adjacent to the central city, traditional middle-income dormitory suburbs, and upscale

suburbs populated by African-American professionals. Some spillover suburbs have

poverty levels almost as great at the central city. Hanlon and Vicino (2007) and Hanlon

(2010) have studied inner-ring suburbs and classify them as stable, declining, or in crisis.

These studies do not include trends in minority group suburbanization. Researchers have

sought to identify additional reasons for this sizable shift of minority populations to the

suburbs. Housing supply is one factor that has been identified. Howell and Timberlake

(2014) found that lower-income African Americans and Hispanics are attracted by the

availability of affordable suburban housing, including subsidized rental housing. The

trend in employment location is another focus of this work. For example, Raphael and

Stoll (2010) found that, among the 50 largest metro areas from 1990 to 2006-07, those

with greater employment decentralization experienced greater population

suburbanization, but not among the poor. And, Somashekhar (2013) finds that, from

1990 to 2010 in the 55 largest metro areas, minority economic status is no better in the

suburbs than in the central city, with the exception of particular minority suburban

locations. This pattern is seen largely as replicating the pattern in central cities.

These studies raise questions and provide suggestions for additional research. First, not

all suburbs are created equal. Some “suburbs” may in fact be cities in their own right

with their own economic bases. Some of these may be adjacent to the primary central

city (Newark, Gary, Camden, East St. Louis, etc.), while others may be satellite cities that

have been absorbed into the expanding large metro area such as Waukegan, Elgin,

Aurora, and Joliet in the Chicago metropolitan area. As Johnson noted, some suburbs are

“spillover” cases that resemble residential areas of the central city. And then there are

what most people likely consider to be suburbs – residential communities dating from

after World War II and which may, or may not, contain a recent suburban employment

center, such as those first identified for metro Chicago by McDonald (1987).2 A more

complete understanding of minority suburbanization should recognize these distinctions.

Second, given these different types of suburbs, which type accounts for the most of the

minority suburbanization? For example, if “suburbanization” means that minorities are

choosing older satellite cities, they may be choosing smaller, segregated central cities.

Or, if spillover suburbs dominate the picture, then one might question whether that is

“suburbanization” at all. Rather, the spillover case may be an extension of the

segregation pattern similar to minority households, some with rising incomes, seeking

better housing within the confines of the central city. In essence, it is suggested here that

a more nuanced understanding of minority suburbanization requires a closer look at the

changing residential spatial patterns in the various types of suburbs.

To repeat, the purpose of this study is to determine which suburban municipalities have

been selected by African-American and Hispanic households in metropolitan Chicago.

What are the characteristics of the municipalities that have attracted these two largest

minority groups? In short, what is the nature of minority suburbanization? The growth

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

of suburban minority group populations has been substantial in metropolitan Chicago,

especially since 1990. McDonald (2018) is a study of that suburban growth since 1970,

and shows that a majority of the Hispanic population in the metro area resides in the

suburbs (60 percent in 2010) and nearly half of African Americans (45 percent) were

suburbanites as of that year as well. However, that study did not focus on the specific

location choices of these groups in the suburbs.

2. Origins of African-American Suburbanization

African Americans have been present in some municipalities in the metro area outside the

city of Chicago for many years. This section briefly recounts that history, with a focus on

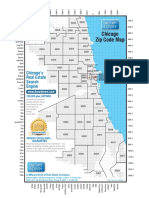

the situation as of 1960. Figure 1 is a map of metropolitan Chicago.

The largest group of African Americans as of 1960 was located in Gary and nearby East

Chicago in Lake County, Indiana. Gary was founded in 1906 by U.S. Steel, and the city

quickly became a center of heavy industry that attracted workers from many locations

including Eastern Europe and the American South. By 1930 the population of the city

was 100,400, including 18,000 African Americans (and 45,000 of Eastern European

stock). In 1960 Gary’s population had increased to 178,300, and as one result of the

Great Migration from the South, the African-American population had grown to 69,000.

In addition the adjacent municipality of East Chicago had its own industrial base and a

population of 57,700, of whom 13,800 were African Americans. Racial segregation

prevailed; African Americans confined to six out of 27 census tracts in Gary and two out

of six tracts in East Chicago. While Lake County, Indiana is often included in the

definition of the Chicago metropolitan area, it would seem that Gary is not a suburb of

Chicago, but rather can be counted as its own central city with its own industrial base.

Indeed, the 1960 Census considered Gary-Hammond-East Chicago in Indiana to be a

separate SMSA. Kitagawa and Taueber (1963, p. 212) noted that 86% of Gary residents

who worked were employed in Gary or East Chicago.

The Illinois portion of the Chicago metropolitan area includes five satellite cities that

were founded in the 19th century. These cities are located about 33-40 miles from

downtown Chicago at the junctions of the radial rail lines built in the mid 19th century

and the outer circumferential rail line built in 1890 (the Elgin, Joliet and Eastern). These

are sizable cities with downtowns and suburbs. Keating (2005) examined the early

history of these railroad age towns. This paper concentrates on the choice of newer

suburban locations, but these older cities are important parts of the story as well.

Table 1 displays the total and African-American populations of these five cities as of

1960, and includes some short comments about the history of each. All five had their

own industrial bases, and very few of the residents were employed in the city of Chicago.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Figure 1: Metropolitan Chicago with Place Names

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 1: Satellite Cities in 1960

City Total African- Comment County

Population American Distance

Population to CBD

Waukegan 55,700 4500 Own industrial base Lake

Great Lakes Naval Training Center 40 mi.

Early free Af. Amer. settlement north

Segregated housing

Elgin 49,400 1600 600 Af. Amer. in Elgin State Hospital, Kane

otherwise no segregation 39 mi.

Own industrial base wnw

Aurora 63,700 2200 Own industrial base, railroads DuPage

No segregation 39, west

Joliet 66,800 4600 Own industrial base, not highly Will

Segregated 38, wsw

Chicago 34,300 6500 Inland Steel plus other industry Cook

Heights Highly segregated 33, south

Another five municipalities in Illinois had at least 2000 African-American residents in

1960. Three of these are suburbs of the central city, one is near Chicago Heights, and the

other is a suburb of Waukegan. These are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Seven Municipalities with at Least 1000 African-American Residents in 1960

Municipality Total African- Comment County

Population American

Population

Evanston 79,300 9,100 Chicago suburb Cook, north

Harvey 29,100 2,000 Chicago suburb Cook, south

Markham 11,700 2,500 Near Chicago Hts. Cook, south

Maywood 27,300 5,200 Chicago suburb Cook, west

North Chicago 22,900 4,600 Suburb of Waukegan Lake, IL

In summary, a total of 118,500 African Americans resided in the five satellite cities in

Illinois plus Gary and adjacent East Chicago, and these other five municipalities listed in

Table 2; of these 16,300 resided in three towns that are suburbs of the city of Chicago.

Including Lake County, Indiana, a total of 977,300 African Americans lived in the

metropolitan area in 1960, of whom 812,600 (83.2%%) lived in the city of Chicago. Of

the remaining 164,700 residents, 118,500 lived in the clusters enumerated in this section.

The remaining 46,200 residents were scattered around the remaining areas of the

metropolitan Chicago, of whom 5,400 lived in suburban Cook County. These data for

1960 will serve as a baseline enumeration of African-American suburbanization.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

3. Minority Group Suburbanization in Metropolitan Chicago

The study area consists of the six counties in Illinois that make up the “traditional”

definition of the Chicago metro area – Cook (the central county), DuPage, Kane, Lake,

McHenry, and Will Counties. Data are displayed in Figures 2, 3, and 4. Lake County,

Indiana (Gary and its suburbs) is included in the table in the Appendix, but is not

included in the computations in this section. The suburban ring is defined as the five

counties, excluding Cook.

As shown in Figure 2, the population of the metropolitan area increased a substantial

12.2% from 1960 to 1970, but grew only by 4.0% from 1970 to 1990. McDonald (2015)

has called 1970-1990 the decades of urban crisis. Population growth resumed to 11.4%

from 1990 to 2000, but has since pulled back to 2.8% in the first decade of the new

century. Except for a 4.0% increase from 1990 to 2000, the population of the city of

Chicago has declined steadily since 1960. Much of that decline has occurred in the

predominantly African-American neighborhoods with a poverty rate of at least 30% at

some time during 1970 to 1990. There are 16 such community areas, and these account

for 65% of the population decline in the central city from 1960 to 2010. In 1960 these

areas accounted for 25.4% of the population of the city, but in 2010 contained only

12.8% of Chicagoans. Data for the 16 areas are in the table in the Appendix. McDonald

(2018) includes a detailed study of these 16 areas.

Figure 2: Population of Metropolitan Chicago

(Six Counties in Illinois: 1000s)

9000

8000

7000

6000 Metro

5000

Chicago

4000

Sub Cook

3000

Sub Ring

2000

1000

0

1960 1980 2000 2015

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Figure 3: African-American Population of Metropolitan Chicago

(Six Counties in Illinois: 1000s)

1600

1400

1200

1000 Metro

800 Chicago

600 Sub Cook

400 Sub Ring

200

0

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2015

Figure 4: Hispanic Population of Metropolitan Chicago

(Six Counties in Illinois: 1000s)

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200 Metro

1000 Chicago

800 Sub Cook

600 Sub Ring

400

200

0

1980 1990 2000 2010 2015

The basic pattern of African-American suburbanization is shown in Figure 3. The

African-American population of the city of Chicago peaked in 1980, and the peak for the

metropolitan area occurred in 2000. From 1960 to 1980 the story is one of rapid growth

in this population of 61.0% at the metropolitan level, 46.1% growth in the city of

Chicago, and 218.2% growth in the suburbs. This is a typical pattern in that rapid

population growth in the metropolitan area results in growth in the central city and very

rapid growth in the suburbs. The largest part of the suburban increase took place in the

Cook County suburbs (66.1% of the 168,000 increase).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

From 1980 to 2000 African-American population growth in the metropolitan area was

only 8.8%. The Great Migration of the African-American population from the South had

ended, and the city of Chicago saw a decline in this group of 11.3%. At the same time

the suburban African-American population doubled from 245,000 to 505,000. Suburban

Cook County captured 68.5% of the increase in the suburbs of 260,000 African

Americans.

The years after 2000 to 2015 produced a decline in the African-American population in

the metropolitan area of 8.2%. The decline in the central city accelerated to 22.2% (over

15 years), and the suburban population growth continued at a slower 21.2% over the 15

years. This outcome suggests that absence of African-American population growth in the

suburbs would require a much larger overall decline at the metropolitan level, an outcome

that would seem to be highly unlikely. The relatively modest suburban growth of

117,000 was divided into two parts, 80,000 in the Cook County suburbs and 37,000 in the

remainder of the suburbs (including the outer suburban ring counties), indicating that

African Americans who decide on a suburban residence are not seeking locations at

greater distance from the old central city.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the Hispanic population of the metropolitan area has more than

tripled since 1980. In 1980 that population was concentrated in the city of Chicago, but

the Hispanic neighborhoods in Chicago seem to have approached effective capacity in

2000. Since 1990 most of the Hispanic population growth has occurred in the suburbs,

both in suburban Cook County and in the rest of the suburban ring in Illinois.

From 1990 to 2010 the total population of the six-county metro area increased by 14.6%.

The population increase of 1,057,000 is largely accounted for by the increase in the

Hispanic population of 957,000. The African-American population increased by only

3.6%, and actually declined by 5.3% from 2000 to 2010. As of 2010 the Hispanic

population outnumbered the African-American population by 21.5% (318,000). The

population of the city of Chicago was stable (down 3.2% from 1990 to 2010), but its

composition changed from 19.2% to 28.9% Hispanic. The total population of the suburbs

increased by 25.6%, and most of that increase stems from the increases in the Hispanic

populations (67.5% of the increase of 1,057,000). All of the suburban counties, including

suburban Cook County, registered large percentage increases in the African-American

and Hispanic populations. Indeed, the Hispanic populations of the five “collar” counties

(excluding suburban Cook) more than tripled. The Hispanic population of suburban

Cook increased by 307,000, and the other five counties had an increase of 406,000.

The big pictures for these two groups are sharply different. The African-American

population grew very little, and in net terms was moving out of the city of Chicago to the

suburbs. This population in the central city fell by 188,000 and grew by 240,000 in the

suburbs from 1990 to 2010. In contrast, the Hispanic population grew very rapidly. The

increase in the central city was 244,000, and was 713,000 in the suburbs. The central city

was one location choice for Hispanics, but it could not have contained most of the large

growth.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Data at the county level can provide more detail. Table 3 shows the total population and

the percentages of African-American and Hispanic population for 1990 and 2010. The

suburban areas closest to the city of Chicago are Suburban Cook, DuPage, and Lake

Counties. Kane, McHenry, and Will Counties are located at greater distances from the

central city. Two immediately obvious facts are: Percentage population growth was

much greater in the more remote counties, and the percentage of African-American and

Hispanic populations increased in every suburban county (except African-Americans in

Kane County). More detailed examination of Table 3 reveals that the more remote

counties had very small changes in the percentage of African-American population.

Indeed, Suburban Cook and DuPage are the only counties with an increase in percentage

in excess of 1.0%. While the other four counties did gain African-American residents,

they did so only roughly in step with their 1990 African-American population

percentages.

The pattern for the Hispanic population is quite different. The percentage Hispanic more

than doubled in every county. The total population of Kane County increased from

317,000 to 515,000 in twenty years, and the Hispanic population more than tripled from

44,000 to 158,000, but the percentage Hispanic increased only by a factor of 2.2. The

percentage “multiplier” effect for four other counties (Suburban Cook, DuPage, Lake,

and Will) varied from 2.6 to 3.0. McHenry County had a very small Hispanic population

of 6,000 in 1990, and this group increased to 35,000 in 2010 as the total population of the

county increased from 183,000 to 309,000 to produce a percentage “multiplier” of 3.45, a

misleading figure because of the small initial base.

Table 3 also contains data on private employment for the counties. The ratio of

population to employment shows clearly that the centers of employment are Suburban

Cook and DuPage Counties (although the ratio for Suburban Cook increased between

1990 and 2010). Kane, McHenry, and Will Counties have relatively high ratios of

population to employment; the “bedroom” counties. Lake County falls somewhere in

between with a population/employment in 2010 that is close to that for Suburban Cook.

In short, these data suggest that the rapid population growth rates in the three more

remote counties did not stem largely from movement to (private) employment.

In summary, the data at the county level show that increases in the African-American

population that caused the percentage of this group to increase was confined to the

suburban areas closest to the central city (Suburban Cook and DuPage Counties). On the

other hand, the percentage Hispanic more than doubled in every county area.

Employment data suggest (but does not prove) that rapid population growth in the three

more remote counties was not caused by movement to employment. The next section

examines these trends at the level of the municipality.

10

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 3: Population and Employment Data for Suburban Counties, 1990 and 2010

(Population and employment figures in 1000s)

Suburban DuPage Lake Kane McHenry Will

Cook

Population, 1990 2321 782 516 371 183 357

Percent Af.-Am. 9.7% 1.9% 6.5% 5.8% 0.2% 10.6%

Percent Hispanic 6.8% 4.5% 7.6% 13.9% 3.3% 5.6%

Population, 2010 2515 917 703 515 309 678

Percent Af.-Am. 15.1% 4.5% 6.7% 5.4% 1.0% 11.0%

Percent Hispanic 18.6% 13.3% 19.9% 30.7% 11.3% 15.6%

Pop. Increase 8.4% 17.3% 36.2% 62.5% 68.9% 89.9%

Employment

1990 1046 380 184 120 53 75

2010 993 485 258 156 75 155

Pop./Empl. Ratio

1990 2.22 2.06 2.80 3.09 3.45 4.76

2010 2.53 1.89 2.72 3.30 4.12 4.37

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census and Illinois Dept. of Employment Security.

4. Choice of Suburb by Minority Households: 1990-2010

It is well known that households that move are attracted to locations where similar people

live. It is expected that African-Americans follow African-Americans and Hispanics

follow Hispanics. But is that all there is? Are location choices influenced by other

factors? See Sampson (2012) and Greenlee (2019) for detailed studies of residential

mobility patterns in Chicago. Sampson calls his overall results for the city of Chicago of

the complex social process as “the enduring neighborhood effect.” Greenlee (2019)

provides an up-to-date survey of the literature on residential mobility, and identifies

income as an important factor influencing flows between neighborhoods in Cook County

(including the city of Chicago). However, he was not able to study the impact of race

because it is not included in the data source he employed. As shown below, the data for

the five satellite cities suggest some considerations such as the income level of the

destination and the availability of multi-family housing, and these variables are

examined.

This section is a more detailed study of the suburban location choices made by minority

households during 1990-2010. Data for the study consist of census data for 1990 and

2010 and data provided by Index Publishing Corporation (1996) on numerous features of

suburban municipalities in 1990. The features of the suburbs from these two sources

include:

- Census population; total, African-American, and Hispanic for 1990 and 2010,

11

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

- Census median age, median family income, median housing price, and

poverty rate for 1990,

- Percentage of multi-family housing units in 1990,

- Whether the municipality had regulations regarding mobile homes or house

trailers (including their prohibition) in 1990,

- Whether the municipality had a comprehensive plan in 1990, and

- Whether the municipality had an enterprise zone in 1990.

The study of individual municipalities is conducted for 1990 to 2010 on the grounds that

much of the baseline data are available for 1990 (and not before), and the crash of the

housing price bubble in 2009 and subsequent years may have created a factor that would

alter the earlier trends. Clearly the impact of the crash in the housing market and the

resulting foreclosures and lack of mortgage lending are topics in need of further research.

The data for 1990 were used in the earlier study by McDonald and McMillen (2004) to

determine which types of suburbs adopted what kind of development controls. At that

time all of the suburbs had a zoning ordinance. Development controls fall into three

categories; lower-class regulations (such as regulations regarding mobile homes), quality

regulations (such as a comprehensive plan), and policies to encourage growth (such as an

enterprise zone to encourage growth). The results of the study show that use of these

controls is related to the size, income (and poverty level), and size of minority

populations as one would expect. Larger suburbs have more regulations of all types, and

higher-income suburbs discourage growth and use regulations to promote quality and

prevent lower-class development. Lower-income suburbs and suburbs with larger

minority populations generally do the opposite.

The present study is based on the 109 suburbs with a population of at least 10,000 in

1990 located in suburban Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry, and Will Counties in

Illinois. (Some of the variables used in the study are not available for smaller suburbs.)

The empirical results are presented separately for suburban Cook and the other counties

because the results are different. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 4. The two

samples differ in four respects; Cook County suburbs have larger African-American

population percentages and lower median family incomes, and some have enterprise

zones (13 suburbs), are spillover suburbs (14), and are located at smaller distances from

the Chicago central business district (CBD). The population total for the 109 suburbs

plus the satellite cities constitute 77% of the total population of the suburbs in 1990.

12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 4: Descriptive Statistics for Suburbs in Metro Chicago (Population > 10,000)

Cook County Mean Std. Min. Max.

Sample (n=71) Dev.

Population 1990 28,191 16,813 11,000 76,520

Population 2010 30,038 18,732 10,950 83,890

Af.American pop. 1990 9.94% 19.54 0 83.30%

Af. American pop. 2010 18.16% 27.96 0.25% 93.07%

Hispanic pop. 1990 5.37% 6.38 0.80% 35.80%

Hispanic pop. 2010 16.24% 16.72 1.75% 85.55%

Other population, 1990 84.69% 20.24 10.7% 99.1%

Other population, 2010 65.60% 29.52 5.18% 97.52%

Median income $1990 50,433 16,904 26,530 155,100

Median housing price 1990 $125K $64K $50K $480K

Distance to CBD (mi) 20.19 6.85 10 34

Multi-family housing 1990 25.52% 13.23 3.0% 58.1%

Comprehensive plan 1990 86%

Enterprise zone 1990 17%

Mobile home regs. 1990 55%

Family poverty 1990 3.35% 3.36 0 23.0%

Spillover suburb 20%

Other Five Illinois Counties Mean Std. Min. Max.

Sample (n=38) Dev.

Population 1990 26,244 16245 11,710 100,400

Population 2010 32,808 21,527 13,140 141,900

Af. American pop. 1990 3.23% 6.52 0 33.40%

Af. American pop. 2010 4.96% 6.85 0.35% 30.27%

Hispanic pop. 1990 5.05% 5.64 0.60% 29.80%

Hispanic pop. 2010 15.67% 13.38 2.80% 51.09%

Other population, 1990 91.72% 9.15 52.70% 99.15%

Other population, 2010 79.37% 16.55 42.05 96.20%

Median income $1990 58,870 22,070 27,910 114,100

Median housing price 1990 $131K $60K $37K $391K

Distance to CBD (mi.) 36 19 14 86

Multi-family housing 1990* 27.92% 12.80 8.40 67.00

Comprehensive plan 1990* 97%

Enterprise zone 1990* 0

Mobile home regs. 1990* 53%

Family poverty 1990* 2.75% 2.59 1.00 12.00

* Sample of 32.

13

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Choice of Suburb by African-American Households

Let us examine first the record for the satellite cities in Illinois. African-American

suburbanization included the five satellite cities. Together these five cities in 1990 had a

population of 363,000, of whom 60,000 (16.5%) were African-American. In short, these

cities already had sizable minority populations in 1990. But as of 2010 these cities had

grown to a total population of 573,000. Aurora and Joliet are the two with the largest

population increases, primarily because they were able to annex territory as suburban

populations grew. The African-American population increased to 80,000 (up 33% over

1990). Table 4 shows that these cities had relatively low median family incomes

($31,500 to $41,200 and high percentages of multi-family housing in 1990 (37% to 50%)

compared to most newer suburbs. A sample of 109 suburban municipalities is employed

in the remaining sections of this paper, and for 1990 they have a mean median family

income of $53,400 and a mean for multi-family housing of 26%. The five satellite cities

also possess their own employment bases; figures for 1990 are shown in Table 5.

Minority households evidently were attracted to these older cities with their own

employment bases, sizable supplies of multi-family housing, and relatively low median

family income levels.

Table 5: African-American Population in Five Satellite Cities

Aurora Elgin Joliet Waukegan Chicago

Heights

1990 Population 105.9 77.0 76.8 69.7 34.0

(1000s)

1990 African-American 12.3 5.6 16.5 13.9 11.8

Population (1000s)

2010 Population 197.9 108.1 147.5 89.1 30.3

(1000s)

2010 African-American 20.3 8.0 23.6 16.2 12.4

Population (1000s)

1990 Median Family 39,941 41,190 37,198 34,316 31,534

Income ($)

1990 Percentage 43% 47% 39% 50% 37%

Multi-Family Housing

1990 Private Employment 39,600 34,100 40,200 22,800 16,563

Sources: US Bureau of the Census and Ill. Dept. of Employment Security (1990).

The 71 Cook County suburbs included in Table 4 contained 176,000 African-American

residents in 1990 and 298,000 in 2010, an increase of 122,000. The 14 spillover suburbs

and the other southern Cook County suburbs accounted for 96,000 of that increase (78%).

14

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

The other 40 suburbs had an increase of only 26,000, although 38 out of 40 did have an

increase in African-American residents. The total population of those 40 suburbs went

from 1.1% to 3.0% African American from 1990 to 2010, while the 31 spillover suburbs

and other southern Cook County suburbs increased from 19.9% to 30.7% African-

American. Additional tabulations of the data are in the appendix.

It is well known that many of the southern suburbs of Cook County had relatively low

housing prices. Those 24 suburbs had an average median housing price of only $90,500

in 1990 compared to $143,000 for the other 57 Cook County suburbs in the sample. So

the suburbs of southern Cook County had low housing prices and concentrations of

African-American residents in 1990. Are both factors important determinants of the

percentage of African-American residents in 2010? Or, is one more important than the

other? It turns out that the southern Cook location dominants the effect of low housing

prices.

Table 6:

Dependent Variable: Percentage Population African American: 2010

Variable Cook Cook Cook Cook Cook Other Other

County County County County County not Five Five

Spillovers Counties Counties

Constant 6.152 1.634 16.600 7.299 1.896 1.711 3.586

(3.06) (0.84) (3.71) (1.62) (1.26) (4.62) (3.47)

Af. American 1.209 1.077 1.116 1.042 1.098 1.004 0.971

Percent 1990 (13.12) (12.91) (11.69) (12.06) (11.43) (19.56) (18.48)

South Cook 17.246 15.681 7.519

(4.59) (4.38) (2.45)

Median House- -0.030

hold Income (1.93)

Median -0.076 -0.038

Housing Price (2.59) (1.39)

R square 0.714 0.792 0.740 0.798 0.786 0.914 0.922

R sq. adj. 0.710 0.786 0.732 0.789 0.779 0.912 0.918

Sample 71 71 71 71 57 38 38

Estimated equations for Cook County are displayed in Table 6. The first equation simply

makes the percentage of African-American population in 2010 in Cook County a function

of that percentage for 1990. The estimated equation says that a Cook County suburb

added 27.1% (6.2% plus 20.9%) to its African-American population percentage over the

twenty years. However, a look at the raw data shows that the bulk of the increase took

place in the 24 southern suburbs of the county. Recall that this part of the county already

had a large African-American population in 1990. The second equation includes a

dummy variable for the southern Cook County suburbs. The estimated equation says that

the 24 southern suburbs increased their percentage African-American populations by

17.2%, and that the other suburbs did not increase by a statistically amount. (The

15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

constant term of 1.63 is not statistically significantly different from zero, and 1.077 is not

statistically significantly different from 1.0.)

As noted above, the suburbs in southern Cook County had lower housing prices than

suburbs in the other parts of the county. The simple correlation between median housing

price and southern Cook is -0.39. The third column in Table 6 shows that, if the dummy

variable for southern Cook is not included in the model, median housing price does have

a statistically significant effect on percentage African-American in 2010. Note that the

R-square is greater for the model in column 2 with the southern Cook dummy. When

both median housing price and southern Cook are included in the model in column 4, the

median housing price variable loses its statistical significance and the dummy variable for

southern Cook maintains its high level of statistical significance. The tentative

conclusion from this evidence is that the effect of southern Cook County, with its

concentrations of African-American residents, is the more important variable compared

to housing prices in their impacts on percentage African-American residents in 2010.

Several other features of the suburbs were tested, and none were found to add to the

explanatory power of the second equation. These variables include median income,

poverty, multi-family housing, mobile home regulations, enterprise zone, median

population age, and distance to the Chicago CBD, and percentage Hispanic population in

1990.

Removal of the 14 spillover suburbs from the data results in a weaker impact of southern

suburbs.4 The fifth column shows that southern Cook County suburbs (not spillovers)

increased by 7.5%, while other suburbs (not spillovers) did not increase by a statistically

significant amount. And once again the additional variables listed in the previous

paragraph add nothing to the explanatory power of the estimated equation. These

spillover suburbs include relatively higher income Oak Park and Evanston, but as a group

they had a relatively low income of $41,600 in 1990.

A reviewer suggested that the statistical analysis could be supplemented by case studies

of individual suburbs. Dolton in the southern suburbs of Cook County is a good example

of a spillover suburb. Dolton is adjacent to the city of Chicago and its percentage

African-American went from 37.8% in 1990 to 90.4% in 2010. The population of the

town fell from 24,700 to 23,200 in these twenty years. The Hispanic population was not

a large part of the population; 4.4% in 1990 and 2.7% in 2010. The poverty rate was only

4.4% in 1990, but the median house value was quite low at $64,600. Private employment

in the town fell from 4287 in 1990 to 3231 in 2000 as jobs in manufacturing declined

from 1077 to 681, retail trade employment fell from 1443 to 643, and wholesale trade

jobs fell from 405 to 78. Employment gains were recorded in population-serving

services. The ratio of population to employment increased from 5.76 to 7.17. The

poverty rate for 2008-2012 from the American Community Survey was 16.7%, and most

recent figure for 2016 is 26.1%. In short, the spillover suburb of Dolton represents an

expansion into the suburbs of some of the urban problems of its very large neighbor, the

city of Chicago.

16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 6 also contains the estimated equations for the 38 suburbs in other five (“collar”)

counties. The sixth column shows that these suburbs replicated the 1990 percentage

African-American population plus 1.7%. The results for these counties differ from the

results for Cook County in that the median income level in the suburb of 1990 had a

statistically significant negative effect on the percentage African-American in 2010. The

effect is not large; a difference of median income of $33,000 was required to produce a

difference of 1.0% in African-American population in 2010. However, the median

income range in 1990 for these suburbs is quite large – from $26,000 to $155,000. Five

suburbs on the north shore of Lake Michigan had median incomes in excess of $100,000

in 1990. A difference of $70,000 (from $30,000 to $100,000) would have produced a

difference in African-American population of 2.1%. Other variables had no statistically

significant effect on percentage African-American in 2010. These include median

housing price, distance to the CBD, percentage multi-family housing, poverty level,

mobile home regulations, and median age of the population in the municipality.

The 38 suburbs in Table 6 contained 32,200 African Americans in 1990 and 50,400 in

2010. The total population of these 38 suburbs registered an increase in the African-

American population from 3.2% to 5.1% over the twenty years. All 38 suburbs had some

increase in the African-American population.

The overall conclusion for African-American suburbanization from 1990 to 2010 is that

the most popular choices were the spillover suburbs of southern Cook County and the

satellite cities (especially Aurora and Joliet). Nearly all of the suburbs with a population

of at least 10,000 (107 out of 109) had at least a small increase in African-American

residents.

Choice of Suburb by Hispanic Households

The satellite cities in Illinois all registered large increases in their Hispanic populations

from 1990 to 2010. Data are displayed in Table 7. The city of Aurora almost doubled in

population (from 106,000 to 198,000), and its Hispanic population increased from 24,000

to 82,000. Similarly, the city of Joliet almost doubled in population (77,000 to 147,500)

and registered an increase in its Hispanic population from 9,500 to 41,000. Elgin and

Waukegan had smaller, but still large, population increases, and tripled in Hispanic

population from around 15,000 to almost 48,000. The Hispanic population of these four

satellite cities increased 155,000, from 63,000 to 218,000. The city of Chicago Heights

lost population, but gained 5,300 Hispanic residents. However, as a group the four

satellite cities with large population increases had Hispanic population increases roughly

in line with the simple models in Table 8 below. The four cities began with a combined

population of 329,000 in 1990, of which 19.25% was Hispanic. These cities increased to

a combined population of 543,000 in 2010, with Hispanic population of 40.1%. In short,

the percentage Hispanic doubled, plus a little more.

17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 7:

Hispanic Population in Five Satellite Cities

Aurora Elgin Joliet Waukegan Chicago

Heights

1990 Population 105.9 77.0 76.8 69.7 34.0

(1000s)

1990 Hispanic 23.9 14.2 9.5 15.8 5.0

Population (1000s)

2010 Population 197.9 108.1 147.5 89.1 30.3

(1000s)

2010 Hispanic 81.8 47.2 41.1 47.6 10.3

Population (1000s)

1990 Median Family 39,941 41,190 37,198 34,316 31,534

Income ($)

1990 Percentage 43% 47% 39% 50% 37%

Multi-Family Housing

1990 Private Employment 39,600 34,100 40,200 22,800 16,563

Sources: US Bureau of the Census and Ill. Dept. of Employment Security (1993).

As noted above, in contrast to African Americans, the Hispanic population in both Cook

County and the other five Illinois counties show sizable increases from 1990 to 2010.

Table 4 shows that the mean values for percentage Hispanic increased from a little over

5% in 1990 to about 16% in 2010 in both areas – a tripling in twenty years. Models of

suburban choice are displayed in Table 8. The first column shows that the percentage

Hispanic for Cook County suburbs increased by a factor of 2.22 plus 4.2 percentage

points. The estimated equation in the second column adds a dummy variable for the

western suburbs of Cook County. The coefficient for this variable 5.7 shows that the

Hispanic population was attracted to a cluster of suburbs in the western Cook area. These

include Cicero, Berwyn, Melrose Park, and Westchester. Median housing price, median

income, multi-family housing, poverty rate, mobile home regulations, enterprise zone,

and distance to the CBD had no effect on the dependent variable. The percentage

African-American in the suburb in 1990 was tested and found to have a coefficient of

negative 0.079, but the t-value for the coefficient is only 1.48 (statistically significant at

only the 86% level).

There are seven suburbs that can be considered spillover suburbs for the Cook County

Hispanic population.5 These seven had a mean value of 12.5% Hispanic in 1990, and the

mean increased to 35.0% in 2010. In short, these seven had a tripling of the percentage

Hispanic. However, this increase is not out of line with the other suburbs that began with

a smaller percentage Hispanic base. According to the estimated equation in column 1 of

Table 8, a suburb that began with 12.5% Hispanic in 1990 would have had a 32%

Hispanic population in 2010. Inclusion of a dummy variable for the seven spillover

suburbs in the model yields no increase in explanatory power. Cicero was the suburb

with the largest Hispanic population in 1990 – 25,600. The population of Cicero

increased from 71,600 in 1990 to 83,800 in 2010, and the Hispanic population increased

18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

to 72,600. The increase from 35.8% to 86.5% is in line with the simple model in column

1 of Table 8 (multiply the 1990 percentage by 2.223 and add 4.23% to get 83.8%).

The results for the other five Illinois counties in column 3 of Table 8 indicate a finding

that is quite similar to the result for Cook County. Percentage Hispanic population in the

suburbs in these two counties increased by a factor of 2.05 plus 5.33 percentage points.

However, the results in column 4 are different from the Cook County results in column 2.

Median income is a statistically significant determinant of percentage Hispanic in 2010.

The effect of median income is -0.128 percent per $1000. This effect potentially is large

because median income varies by a sizable amount in these counties. Median income

varied from $28,000 to $114,000. A difference of $80,000 translates into a difference in

percentage Hispanic of 10.2 percentage points. Median housing price and the other

variables listed in Table 4 had no statistically significant impact on the percentage

Hispanic in 2010.

The empirical results for both Cook County and for the other five Illinois counties show

that the Hispanic population tended to be attracted to suburbs with Hispanic residents in

1990. A coefficient of 2.0 on percentage Hispanic in 1990 means that the Hispanic

population doubled, so the suburb with the larger percentage Hispanic in 1990 had the

larger absolute increase in that population for 2010. (In contrast, the coefficient of 1.0 for

percentage African-American in 1990 means that, unless some other factor is at work,

that percentage simply replicates itself in 2010.) Hispanics were attracted to a cluster of

suburbs in western Cook County. Suburbs in the other five Illinois counties with higher

incomes in 1990 had smaller increases in percentage Hispanic, but this effect is not

evident for Cook County.

Cicero is the iconic spillover suburb for Hispanics. It is located adjacent to the large

Hispanic area on the west side of the city of Chicago. As noted above, the population

increased from 71,600 in 1990 to 83,900 in 2010, and the percentage Hispanic increased

from 35.8% to 86.5%. With 72,600 residents, Cicero has by far the largest number of

Hispanics in the metro area outside the cities of Chicago and Aurora. The adjacent

suburb of Berwyn had 33,700 Hispanic residents as of 2010 (59.5%). The poverty rate in

Cicero was 11.0% in 1990, and it increased to 18.7% for 2008-2012. Changing

employment industry and location patterns were not kind to Cicero. The Cicero

Industrial District, which no longer exists, was once home to the Hawthorne Works of

Western Electric and home appliance firm Sunbeam. Total private employment fell from

19,700 in 1990 to 13,200 in 2010. The town registered a major losses of manufacturing

employment from 7900 to 2900 and wholesale trade jobs from 1440 to 660. These two

industries account for 89% of the employment decline. Cicero is literally an example of

spillover from the rapidly-growing Hispanic population next door in the city of Chicago.

McDonald (2018) reports that the nine community areas that make up the Hispanic area

on the southwest side of the central city increased in population from 121,000 in 1980 to

256,000 in 2010. Cicero, with its increase of 47,000 from 1990 to 2010, is a

straightforward extension of that population growth among Hispanics.

19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Palatine in the northwestern portion of Cook County is an example of a newer suburb that

is not near the central city. It can serve as a case study for both the African-American

and Hispanic groups in suburbs of this type. The population of Palatine increased

rapidly from 41,400 in 1990 to 68,600 in 2010, but the percentage of African-American

residents increased only slightly from 0.9% to 2.6% (from a headcount of 373 to 1798).

In contrast, the Hispanic population of Palatine increased from 3.7% in 1990 to 18.0% in

2010 (almost five times as large). Median income was $57,500 in 1990, which was

typical for a suburb in that vicinity, and the poverty rate was 2.0%. Private employment

in Palatine increased from 18,400 to 23,800 as 4400 jobs that were lost in manufacturing,

retailing, and wholesale trade were offset by gains in services. The ratio of population to

employment ratio increased from 2.25 to 2.88, and the poverty rate for 2008-2012 was

8.5%. But the location of Palatine in the northwestern suburbs of Cook County does

provide reasonable access to the suburban employment centers identified by McMillen

and McDonald (1998) of Schaumburg, Des Plaines, and O’Hare. These three subcenters

provided employment for 101,000 workers in 1990. Some of the Hispanic population

was able to move to Palatine and its general access to employment, but it also seems that

this group brought some poverty as well. However, only a few African-Americans were

able to move there..

Wheaton can be used as another example of a commuter suburb. Wheaton is located in

the center of DuPage County, and its origin dates back to the railroad age. Its population

was static; 53,760 in 1990 and 52,900 in 2010. The African-American population

increased from 1450 to 2320 (from 2.7% to 4.4%) over the twenty years – in line with the

general suburban increase of 1.7% in the five collar counties. The Hispanic population

also increased from 2.0% to 4.9% of the town’s population (from 1075 to 2620). The

percentage Hispanic increased by a factor of 2.45, which is smaller than the increase for

DuPage County as a whole of 2.95. One reason for its relatively low increase in

percentage Hispanic may be the employment figures. Private employment in Wheaton

declined from 18,500 to 15,600 from 1990 to 2010. The drop in employment is

accounted for entirely by the drop in manufacturing employment from 3700 to 430.

Wheaton did experience an increase in the poverty rate from 2.0% to 6.4% over the

twenty years. The employment decline in Wheaton may have accounted both for the

increase in poverty and the relatively small increase in the Hispanic population for a town

in DuPage County.

Naperville is located just to the East of Wheaton, but represents a very different story in

comparison. Miller (2013) calls Naperville a “boomburb” because of its rapid growth

after 1970. Naperville is part of what is called “Silicon Prairie” because of its high-tech

employment base. AT&T and Bell Labs have major research facilities in the suburb.

Population increased from 100,400 in 1990 to 141,900 in 2010 as the town was able to

annex territory. Employment in 1990 was 40,500, including 8100 retailing jobs and 7900

jobs in engineering, management, and related services. There were 60,000 jobs located

in Naperville in 2010, up 48.2% from 1990 (compared to population growth of 41.3%).

Those jobs included 9500 in professional, technical, and scientific services. Median

household income was $68,900 and house value was $176,000 in 1990. These figures

were exceeded in DuPage County only by Hinsdale, a small very high-income suburb

20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

(median income of $82,600). And the poverty rate was just 1.0%. The African-

American population in Naperville was 1900 in 1990 (1.9%), and increased to 6500 in

2010 (4.6%). The Hispanic population numbered 1800 in 1990 (1.8%), and also

increased in 2010 to 7600 (5.3%). The increase in the percentage Hispanic is in line with

the general tripling rule for 1990-2000. However, the increase of 2.7% in the African-

American percentage is a bit larger than the 1.7% typical for the collar counties.

Nevertheless, these minority groups were not very successful at joining “boomburb.”

The simple summary for the empirical study of the Hispanic population from 1990 to

2010 is that the percentage Hispanic population more than doubled. This equation works

for suburbs that began with small and large percentage Hispanic populations in 1990.

This rule even works for the rapidly-growing satellite cities. It says that Hispanics tended

to locate where there were already concentrations of Hispanic people. A more detailed

reading is that, in the other five Illinois counties, Hispanics tended to locate in suburbs

with lower median incomes in 1990. This point about incomes also applies to the

satellite cities, which were not places of high median incomes in 1990.

Table 8

Dependent Variable: Percentage Hispanic Population in 2010

Variable Cook Cook Other Other

County County Five Five

Counties Counties

Constant 4.238 2.724 5.331 13.810

(3.10) (1.90) (3.56) (3.78)

Hispanic 2.224 2.141 2.048 1.866

Percent 1990 (13.56) (13.24) (10.26) (9.34)

Western Cook 5.715

County (2.66)

Median Income -0.128

1990 (2.52)

R squared 0.727 0.753 0.745 0.827

R sq. adj. 0.723 0.744 0.738 0.809

Sample size 71 71 38 38

5. Choice of Suburbs by Whites and Other Groups

A reviewer suggested that this study should also include an examination of suburbs

chosen by whites and other groups. Whites make up the vast majority of the total of

these groups. In 2010 87% of these groups in Cook County were non-Hispanic whites,

and non-Hispanic whites were 90% of these groups in the other five counties. Asians are

the next-largest group and made up 6% of the six-county suburban population in 2010.

Asians are not highly segregated from the suburban white population. See McDonald

(2018) for an examination of suburbanization by Asians. These groups, including whites,

will be referred to in this section as “others.” Table 4 shows that, as the African-

21

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

American and Hispanic populations in the suburbs in the sample of 109 increased from

1990 to 2010, the mean percentage of whites and other groups declined in both the Cook

County suburbs and the suburbs of the other four Illinois counties. In Cook County the

decline is from a mean of 84.7% to 65.6%, and the other five counties experienced a

decline from a mean of 91.7% to 79.4%.

Models of the “other” percentages in the suburbs are shown in Table 9. The basic result

for Cook County suburbs in the first column of results is that suburbs had a decline in the

percentage of white and other population groups. The negative effect of a 36.4% loss is

offset by the effect of the existing percentage population in 1990 times 1.2. For example,

according to the equation a suburb that was 99% “other” in 1990 would have declined to

82.4% “other” in 2010. The inclusion of median income improves the explanatory power

of the model, as shown in the second column of results in Table 9. A suburb with a

median income of $100,000 and 85% “other” groups in 1990 is estimated not to have

experienced a decline in these groups. Also, the dummy variable for the southern

suburbs of Cook County attains marginal statistical significance. These suburbs were the

choice of many African-Americans, and tended to have the other groups move out (or not

choose to move there).

The basic estimated model for the other five counties in the fourth column of results in

Table 9 also shows that the tendency to have a decline in the “other” groups is partly

offset by the initial percentage of these groups. A suburb at the mean of 91.7% in 1990 is

estimated to have been 79.3% white and other groups in 2010. A suburb that was 99%

“other” in 1990 is estimated to have been 90.8% white and other in 2010. The addition

of median income in 1990 to the equation shows that suburbs with higher incomes had

smaller declines in the percentage the “other” groups. For example, a suburb with a

$100,000 median income and 91.7% “other” groups in 1990 is estimated to have been

87.0% “other” groups in 2010. As it turns out, the median house price for the suburb in

1990 is a slightly better predictor of percentage of white and other groups for 2010 than is

median income. The last column in Table 9 shows the result of replacing median income

with median house price. Suburbs with higher housing prices in 1990 tended to

experience smaller declines in the percentage of the white and other population groups.

As one would expect, median income and median house price are highly correlated

(simple correlation of 0.60).

The short summary for the white and other groups is that the general tendency for the

percentage to decline in the suburbs was partly offset by higher median income and/or, in

the case of the suburbs in the other four Illinois counties, partly offset by more expensive

houses. These positive effects for median income and median house price mirror their

negative effects for the percentages African-American and Hispanic shown in Tables 6

and 8 above.

22

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 9:

Dependent Variable: Percentage Population Other Than African-American or Hispanic

Cook Cook Cook

Other Other Other

County County County

Five Five Five

Counties Counties Counties

Constant -36.383 -45.830 -38.121 -65.468 -58.637 -57.274

(4.22) (5.36) (4.11) (4.82) (4.51) (4.46)

Percent Other 1.204 1.079 1.045 1.579 1.403 1.400

Population 1990 (12.15) (10.80) (10.50) (10.73) (9.04) (9.30)

Median Income 0.397 0.355 0.159

1990 (3.32) (2.97) (2.47)

South Cook -7.893

(1.95)

Median House 0.063

Price 1990 (2.74)

R-squared 0.682 0.726 0.741 0.762 0.797 0.804

Adj. R-sq. 0.677 0.718 0.729 0.755 0.785 0.792)

Sample Size 71 71 71 38 38 38

A reviewer suggested that it would be useful to know the conditions under which an

increase African-American and/or Hispanic populations would actually reduce the

number of the whites or other groups. The answer depends at least in part upon the

growth of the population in the suburb. Descriptive statistics for the total population

growth and population growth (or decline) of the “other” groups for the 109 suburbs are

shown in Table 10. Table 10 also includes descriptive statistics for the Hispanic

population in the suburbs in 1990.

Table 10: Descriptive Statistics for Population Changes: 1990-2010

Mean Std. Dev. Minimum Maximum Sample

Size

Total Population 1960 5258 -9718 27,160 71

Growth, Suburban Cook

“Other” Population -3634 7248 -37,230 14920 71

Growth, Suburban Cook

Hispanic Population, 1636 3143 98 25,630 71

Suburban Cook, 1990

Total Population 6563 8673 -2404 41,430 38

Growth, Five Counties

“Other” Population 2111 7155 -7039 31,050 38

Growth, Five Counties

On average the suburbs in Suburban Cook County lost 3634 “other” residents, while the

suburbs in the other five counties gained 2111 residents in the “other” groups.

23

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Furthermore, average population growth in the suburbs of the other five counties of 6563

far exceeds the average growth of 1960 for the Suburban Cook suburbs.

The model to be estimated simply relates the change in the “other” groups to the change

in the total population of the suburb. The results for the two groups of suburbs are shown

in Table 11. The results for Suburban Cook show that, if there is no total population

change, the suburb would lose 4389 “other” residents. The coefficient of total population

change of 0.385 means that total population growth of 11,400 would have been required

to maintain the population of the “other” groups. Recall that the mean total population

growth was 1960. Only 8 suburbs out of 71 did not lose “other” population. Those eight

include Lincolnwood and Western Springs in western Cook; Bartlett, Glenview, and

Palatine in northern Cook; and Matteson, Orland Park, and Tinley Park in southern Cook.

Note that, while the coefficient of the total population change variable is statistically

significantly greater than zero, the estimated equation has a low level of explanatory

power. Further examination of the data reveals that the presence of Hispanic population

in the suburb in 1990 is associated with the loss of “other” population in 2010. The

second column of results in Table 11 shows that by 2010 a suburb had gained 0.65

“other” persons for each increase in population headcount from 1990 to 2000, and had

lost 1.7 “other” persons per 1.0 Hispanic person in 1990. In other words, a suburb with

no Hispanic population in 1990 and no population growth from 1990 to 2000 would have

lost 2132 “other” population, and would have lost 1270 “other” population if population

growth had been the mean of 1960. However, a suburb with no population growth and

the mean number of Hispanic population in 1990 of 1636 would have experienced a loss

of other population of 4043. A suburb with the mean values for population growth of

1960 and mean Hispanic population of 1636 in 1990 is estimated to have lost 2773

“other” headcount.

In contrast, the results for the other five counties tell a different story. If there is no total

population growth in the suburb, it loses 2504 “other” residents. However, the mean for

total population growth is 6563. Total population growth of 3562 was needed to

maintain the level of the “other” population groups. Almost half (18) suburbs out of 38

lost “other” population. And the estimated equation has a high level of explanatory

power (R-squared of 0.727).

See Figure 4 for a map depicting population increase and loss by ethnic group for 2000 to

2010. White population increases took place near downtown Chicago and in the fringe

areas of the metropolitan area. The largest increases for the African-American

population are located in the north, northwest and southwest suburbs, and Hispanic

increases were in the central city, satellite cities, near west, and many other suburbs.

24

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Table 11: Population Growth of “Other” Population Groups

As a function of Total Population Growth in a Suburb: 1990-2010

Suburban Suburban Other Five

Cook County Cook County Counties

Constant -4389 -2132 -2504

(4.94) (3.27) (3.23)

Total Population 0.385 0.648 0.703

Change in Suburb (2.42 (5.79) (9.78)

Hispanic Population -1.695

in Suburb, 1990 (9.06)

R-squared 0.078 0.582 0.727

Adj. R-sq. 0.065 0.570 0.719

Sample Size 71 71 38

6. Conclusion

One overall conclusion is that both African-Americans and Hispanics during 1990 to

2010 tended to select suburbs containing residents of their own ethnic group, moderated

somewhat by the income level (or house price level) in the suburb as of 1990. The very

simple models of this type provide high levels of explanatory power for the percentages

of each minority group in suburbs in 2010. However, these two groups had very different

suburbanization experiences. The Hispanic population grew rapidly and its percentage in

a suburb approximately tripled from1990 to 2010. In contrast, the African-American

population grew slowly and tended to locate in spillover suburbs and other suburbs in

southern Cook County. Nevertheless, nearly all of the suburbs in the study experienced

an increase in both minority groups. The rest of the population (overwhelmingly whites)

had declining percentages in most suburbs over these twenty years. In suburbs with slow

(or negative) population growth, this meant that fewer numbers of whites and other

groups remained.

A related development is that the high-poverty African-American areas in the central city

lost more than half of their population. McDonald (2018) contains a detailed breakdown

of the high-poverty community areas in the city of Chicago from 1970 to 2010. In 1990

there were 11 community areas with a total population of 280,000 and poverty rates in

excess of 40% (average of 54%). In 2010 there were “only” six community areas

(population 113,000) with poverty rates in excess of 40%. The reasons for the decline in

concentrated poverty are another topic in need of further research.

Downs (1973) admitted that his plan for “opening up the suburbs” would be very difficult

to implement, and almost 50 years of history have demonstrated that statement in

metropolitan Chicago. What conclusions can be reached now for making the suburbs

25

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

open wider to minority groups? First, the evidence from spillover suburbs is that many

African-Americans and Hispanics follow their own groups. This is not necessarily a bad

thing, but some of those spillover suburbs may not have the capacity to deliver high-

quality educational and other services. And they do not have the ability to attract

employment as well as other municipalities. What about Dolton, for example? Some of

the spillover suburbs need help from high-level, county and/or state, government. The

satellite cities in Illinois are doing pretty well, with the exception of Chicago Heights.

Chicago Heights seems to fall into the group of southern Cook County suburbs in need to

assistance from higher levels of government. Both Aurora and Joliet have large and

growing employment bases and are attracting minority residents, but more open housing

efforts for African-Americans seem to be in order (see Table 5).

What about the large number of newer suburbs not in southern Cook County? Some of

them have the ability to attract more employment (Naperville), while others do not

(Palatine, Wheaton). Most of them appear to have the ability to deliver good public

services, but most have only small numbers of African-American residents – and larger

numbers of Hispanic residents. Downs wanted to “open” these suburbs, and they are

more open now than they were. Can we just wait and hope that the emerging openness

will continue, or does society need to take further action? How about more housing

choice vouchers, with the stipulation that each suburb must have some vouchers to

distribute? Maybe we need to be reminded of the Oak Park Regional Housing Center, the

non-profit agency devoted to open housing in that suburb adjacent to the west side of the

city of Chicago since 1972. Carole Goodwin (1979) studied the Center, and its work has

been examined many times since. Oak Park has a stable African-American percentage of

about 20% (18% in 1990 and 21% in 2010). Can the Oak Park model work on a larger

scale? But, as a recent television series reported, the Oak Park school system has some

difficult challenges – but adequate resources at its disposal.

26

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Figure 4: Population Gains and Losses, 2000-2010

27

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Notes

1. Orfield and Luce (2013) classify suburbs as predominantly white, divers (20% to 60%

non-white) predominantly non-white (more than 60% nnm-white), and exurban. Non-

white includes African-Americans, Hispanics – and others. A recent study by Greenlee

(2019) of Cook County (the county in which the city of Chicago is located) classified

suburban census tracts as affluent, older, developing, or diversifying. His results for

residential mobility are somewhat similar to the findings in this study.

2. Daniel McMillen and John McDonald have done a series of studies on suburban

employment centers in metropolitan Chicago. See McMillen and McDonald (1998) for

the subcenters identified for 1990. Subcenters are classified based on age and

composition of employment as of 1980. These include old satellite cities, old industrial

suburbs, post-World War II industrial suburbs, new industrial and retail suburbs, edge

cities, and service and retail centers.

3. The largest clusters of African-Americans outside the southern suburbs of Cook

County are Bollingbrook (DuPage County with 6600 in 1990 and 14,700 in 2010), North

Chicago and Zion (adjacent to Waukegan in Lake County, with 16,200 in 1990 and

16,900 in 2010 together), Evanston (North Cook County, with 9100 in 1990 and 13,100

in 2010), Bellwood (Central Cook County, with 15,100 in 1990 and 14,200 in 2010),

Maywood (Central Cook County, with 23,700 in 1990 and 17,800 in 2010), and Oak Park

(Central Cook, with 9900 in 1990 and 11,000 in 2010). The four in Cook County are

spillover suburbs

4.. The spillover suburbs are Oak Park, Evanston, Forest Park, Maywood, Bellwood,

Skokie, Blue Island, Dolton, Harvey, Hazel Crest, Homewood, Riverdale, and South

Holland.

5. These are Cicero and Berwyn in Central Cook County, Evanston and Skokie and in

North Cook County, and Blue Island, Calumet City, and Harvey in South Cook County.

28

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Appendix

Data Sources

The paper relies primarily on data from the U.S. Bureau of the Census for 1990

and 2010. Some data for small suburbs with population under 10,000 are not available

for 1990, evidently because of small sample sizes for the long form. However, absence

of smaller suburbs from the data is not a serious limitation because, as noted above, the

total population for the satellite cities and the 109 suburbs used in the statistical tests

constituted 77% of the total suburban population in 1990. Census data for 1990 are

compiled by The Chicago Fact Book Consortium (1995). Employment data for counties

and municipalities are provided by the Illinois Department of Employment Security

(1990 and 2010). These data are for private employment covered by the State of Illinois

unemployment insurance system. The data from 2001 forward are posted on the IDES

web site under Where Workers Work. This convenient source of data down to the ZIP

Code level is not as readily available in some other metro areas around the nation. Data

on the municipal planning ordinances are provided in Index Publishing Co. (1996).

Additional tabulations of the sample of 109 suburbs are available upon request. Data for

Figures 2, 3, and 4 are shown below.

29

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

Population of Metropolitan Chicago: 1960-2015 (1000s)

Area 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2015**

(est.)

Metropolitan Area

Total 6222 6979 7108 7260 8087 8317 8400

African-American 890 1233 1433 1425 1559 1477 1432

Hispanic n.a.* n.a.* 584 838 1410 1795 1913

(Six counties in Illinois)

City of Chicago

Total 3550 3363 3005 2784 2896 2696 2723

African-American 813 1102 1188 1076 1054 888 820

Hispanic n.a. n.a. 422 535 754 779 790

16 high poverty areas*** 902 753 555 428 384 346 345

Suburban Cook County

Total 1580 2129 2249 2321 2481 2499 2516

African-American 48 79 158 225 336 378 406

Hispanic n.a. n.a. 68 159 318 466 522

Rest of Suburban Ring

Total 1092 1487 1854 2155 2710 3122 3111

African-American 29 52 87 124 169 211 206

Hispanic n.a. n.a. 94 144 338 550 601

Lake County, Indiana

Total 574 546 523 476 485 496 489

African-American 87 112 110 100 102 118 117

Hispanic n.a. n.a. 42 43 58 93 90

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census. Metropolitan area is Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake,

McHenry, and Will Counties in Illinois. Rest of Suburban Ring consists of DuPage,

Kane, Lake, McHenry, and Will Counties.

*Hispanic and Asian populations not enumerated consistently with later censuses.

**2015 estimates from American Community Survey for 2013-2017.

***Predominantly African American community areas with 30 percent poverty or higher

at some time from 1970 to 2000.

30

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572078

References

Chicago Fact Book Consortium. (1995). Local Community Fact Book: Chicago

Metropolitan Area 1990, Chicago. Academy Chicago Publishers for the Board of

Trustees, University of Illinois.

Downs, Anthony. (1973). Opening Up the Suburbs. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Frey, William H. (2011). Melting pot cities and suburbs: Racial and ethnic change in

metro America in the 2000s. Brookings Institution, Washington DC, May.

Goodwin, Carole. (1979). The Oak Part Strategy: Community Control of Racial Change,

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greenlee, Andrew. (2019). Assessing the intersection of neighborhood change and

residential mobility pathways for the Chicago metropolitan area. Housing Policy

Debate, 25(1), 186-212.

Hanlon, Bernadette, and Vicino, Thomas. (2007). The fate of inner suburbs: Evidence

from metropolitan Baltimore. Urban Geography, 28(3), 249-275.

Hanlon, Bernadette, (2010). Once the American Dream: Inner-Ring Suburbs of the

Metropolitan United States. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Howell, Aaron, and Timberlake, Jeffrey. (2014). Racial and ethnic trends in the

suburbanization of poverty in U.S. metropolitan areas, 1980-2010. Journal of

Urban Affairs, 36(1), 79-98.

Illinois Department of Employment Security. (1990 and 2010). Where Workers Work,

Chicago: IDES.

Index Publishing Co. (1996). Suburban Fact Book. Chicago, IL: Index Publishing Co.

Johnson, Kimberly. (2014). ‘Black’ suburbanization: American dream or the new

banlieue? Citiespapers, July.

Keating, Anne Durkin. (2005). Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kitagawa, Evelyn and Taeuber, Karl. (1963). Local Community Fact Book, Chicago