Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Challenges To Online Medical Education During The COVID-19 Pandemic

Uploaded by

Zeeshan KhanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Challenges To Online Medical Education During The COVID-19 Pandemic

Uploaded by

Zeeshan KhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Original

Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.8966

Challenges to Online Medical Education

During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Mohammad H. Rajab 1 , Abdalla M. Gazal 2 , Khaled Alkattan 2

1. Epidemiology and Public Health, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, SAU 2. Internal Medicine, Alfaisal

University, Riyadh, SAU

Corresponding author: Mohammad H. Rajab, mhrajab@yahoo.com

Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has impacted all aspects of our lives,

including education and the economy, as we know it. Governments have issued stay-at-home

directives, and as a result, colleges and universities have been shut down across the world.

Hence, online classes have become a key component in the continuity of education. The

present study aimed to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online education at

the College of Medicine (COM) of Alfaisal University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Between March

and April 2020, we emailed a survey to 1,289 students and faculty members of the COM. We

obtained 208 responses (16.1%); 54.8% of the respondents were females, and 66.8% were

medical students; 14.9% were master’s students, and 18.3% were faculty. Among the

respondents, 41.8% reported having little or no online teaching/learning experience before the

pandemic, and 62.5% preferred blending online and face-to-face instruction. The reported

challenges to online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic included issues related

to communication (59%), student assessment (57.5%), use of technology tools (56.5%), online

experience (55%), pandemic-related anxiety or stress (48%), time management (35%), and

technophobia (17%). Despite these challenges, most of the respondents (70.7%) believed that

the COVID-19 pandemic has boosted their confidence in the effectiveness of online medical

education. Consequently, 76% of participants intended to integrate the online expertise

garnered during the pandemic into their practice. In short, the modern study demonstrated a

largely positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online medical education.

Categories: Medical Education, Public Health, Epidemiology/Public Health

Keywords: coronavirus pandemic, covid-19, alfaisal university, online medical education, face-to-face-

instruction

Introduction

A growing number of colleges and universities have been implementing a transition from

Received 06/12/2020

traditional face-to-face teaching methods to online teaching or a combination of online and

Review began 06/25/2020

Review ended 06/26/2020 traditional teaching (blending) [1]. The blended method of teaching involves replacing part of

Published 07/02/2020 the face-to-face interaction with online instruction [2]. As online education continues to grow,

a study in the United States has reported that many educators are just beginning to transform

© Copyright 2020

Rajab et al. This is an open access their face-to-face teaching to an online environment [3].

article distributed under the terms of

the Creative Commons Attribution

Currently, the world is responding to a pandemic of contagious respiratory disease caused by a

License CC-BY 4.0., which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and

novel coronavirus, named COVID-19 [4]. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization

reproduction in any medium, provided declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, i.e., the worldwide spread of a new disease [5,6].

the original author and source are The subsequent implementation of social distancing (i.e., increasing the physical space

credited. between people) during the COVID-19 pandemic has forced colleges and universities to empty

How to cite this article

Rajab M H, Gazal A M, Alkattan K (July 02, 2020) Challenges to Online Medical Education During the

COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966

their classrooms and keep the students away from the institutions [7]. Consequently, there has

been a general shift from traditional face-to-face instruction to online teaching [8]. Most

institutions, including Alfaisal University, have switched to distance learning in the simplest

and most convenient ways possible, including conferencing platforms, email, and phone [8].

There have been two main reported predictions about the potential impact of COVID-19

pandemic on online education. Some experts have predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic

would adversely impact online education for several reasons [7]. Firstly, they felt that the

transition to online education can be challenging, even when the transitioning process is given

enough time [9]. Besides, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is not a single part of the

economy that has been unaffected. As a result, college students have become financially

vulnerable [10]. Some of the students are worried that they will no longer be able to afford

college after the pandemic. Also, being confined at home, some of the faculty and students

have been busy trying to manage their children, other elders, or siblings in the house who are

also not in school [10].

Challenges to online education reported in the medical literature so far include issues relating

to time management, use of technology tools, students’ assessment, communication, and the

lack of in-person interaction [9,11]. Besides, online education may not be equitable in terms of

access and the quality of teaching [10]. Some students do not have access to laptops, or high-

speed internet at home. Also, older internet users benefit the least from online education for

reasons such as technophobia [12]. Many teachers themselves are technophobic, i.e., they are

worried or not confident enough about dealing with computer hardware and software in their

classrooms [13]. Challenges to the online environment during an emergency may delay the

adoption of technology-enabled education [14].

In contrast, other commentators have predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic would have a

positive impact that will lead to wider acceptance of online and technology-enabled education

[8]. Even before COVID-19, there was already a high growth and adoption of education

technology [1,3]. Advocates of this viewpoint believe that online education is as effective as

traditional classroom education [15]. Moreover, switching over to online instruction during an

emergency acts as a reset button to the ailing traditional educational system [10]. The

transition to online education requires the faculty’s support in the universities planning such a

transition. Of note, 80% of institutions surveyed in a study conducted in the United States

confirmed that faculty members are being offered some support for their online courses [16].

The present study aimed to determine and analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

online education at the College of Medicine (COM) of Alfaisal University in Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia.

Materials And Methods

This study was sponsored by Alfaisal University and conducted with the approval of the

university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB-20027). This was a cross-sectional study and was

conducted from March through May 2020. Located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Alfaisal University

is a private, nonprofit, research-based university with five affiliated colleges and over 3,000

students from over 40 nations [17]. The COM offers Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of

Surgery (MBBS) program, and several master’s degree programs, including a Master of Public

Health (MPH) degree program [17].

The study investigators developed a self-administered online questionnaire using Google

Forms® (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA). The survey contained an introductory paragraph

that informed participants of the study’s aims, the confidentiality of their responses, and the

freedom to decline to answer any question or to withdraw from the study altogether. The

questionnaire comprised a combination of closed- and open-ended questions. The closed-

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 2 of 11

ended questions included inquiries into participants’ demographics and their experiences

before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Open-ended questions were designed to elicit

descriptive feedback in the participants’ own words instead of simple “yes” or “no” answers. As

a part of the questionnaire validation process, we invited four faculty members and two

students to pilot-test the initial survey draft. The survey was modified based on their feedback.

To launch the survey, we sent an introductory email to members of the target population,

which consisted of faculty and students of the COM. The initial email informed the target

population of the study’s aims and solicited their participation. Next, the survey’s web link was

sent to the target population using the institutional email system. Subsequently, two follow-up

email reminders were sent to the same groups. We excluded from participation faculty and

students who had participated in the pilot-test of the study questionnaire.

The present study targeted students and faculty who belonged to different generations. The

generations were classified as follows based on the year of their birth: Baby Boomers (1946-

1964), Generation X (1965-1980), the Millennials or Generation Y (1981-1996), and Generation

Z or Post-Millennials (1997-2012) [18]. Baseline and outcome characteristics were summarized

using descriptive statistics, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 208 individuals responded to the survey: 38 (18.3%) faculty, 31 (14.9%) master’s

students, and 139 (66.8%) medical students. The response rates were approximately 53.5%,

62.0%, and 11.9% for faculty, master’s students, and medical students, respectively. Of the

respondents, 114 (54.8%) were females, 125 (60.1%) were born between 1997-2012 (Generation

Z or Post-Millennials), and 66 (31.7%) were born between 1981-1996 (Generation Y or

Millennials). The characteristics of the study respondents are depicted in Table 1.

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 3 of 11

Characteristics N (%)

Gender

Female 114 (54.8)

Male 94 (45.2)

Year of birth

1946-1964 (Baby Boomers) 8 (3.9)

1965-1980 (Generation X) 9 (4.3)

1981-1996 (Generation Y or Millennials) 66 (31.7)

1997-2012 (Generation Z or Post-Millennials) 125 (60.1)

Position

Faculty 38 (18.3)

Master's students 31 (14.9)

Medical students 139 (66.8)

TABLE 1: Characteristics of the study respondents (N = 208)

Among the respondents, 130 (62.5%) preferred combining online with traditional face-to-face

instruction, 53 (25.5%) preferred traditional face-to-face instruction, and only 25 (12.0%)

preferred online instruction alone. The acceptance of blending online and face-to-face

instruction has been growing in the academic community [2]. Participants’ teaching/learning

preferences before the COVID-19 pandemic are presented in Table 2.

Preferences N (%)

Combining online with face-to-face instruction 130 (62.5)

Face-to-face instruction 53 (25.5)

Online instruction 25 (12.0)

TABLE 2: Teaching/learning preferences before the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

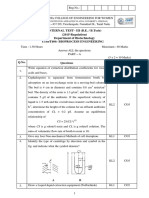

When asked to describe their online teaching/learning experience before the pandemic, 57.9%

of the faculty, 42% of master’s students, and 37.4% of medical students reported having little or

no experience. Online teaching/learning experience before the COVID-19 pandemic by position

is presented in Figure 1.

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 4 of 11

FIGURE 1: Online learning/teaching experience before the

COVID-19 pandemic by position

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

The reported challenges to online education during the COVID-19 pandemic at this institution

included issues regarding in-person communication (59%), student assessment (57.5%), use of

technology tools (56.5%), experience in online education (55.0%), pandemic-related anxiety

and stress (48%), learning curve (35.5%), time management (35.0%), students' evaluations of

faculty (24.0%), and technophobia (17.0%). Challenges to online education during the COVID-

19 pandemic are presented in Table 3.

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 5 of 11

Challenges N (%)**

Communication 118 (59.0)

Student assessment 115 (57.5)

Use of technology tools (access to hardware and software) 113 (56.5)

Experience in online teaching/learning 110 (55.0)

Mental health (stress, anxiety) 96 (48.0)

Learning curve (adapting to unfamiliar technology) 71 (35.5)

Time management 70 (35.0)

Students' evaluations of faculty 48 (24.0)

Technophobia 34 (17.0)

Other 9 (4.5)

TABLE 3: Challenges to online education during the COVID-19 pandemic (N = 200)*

*Eight responses were missing; **Check all that apply

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

The main question in the present study was about assessing the impact of the shift to online

education during the pandemic. Remarkably, 70.7% of the study respondents reported

increased confidence in the effectiveness of online teaching and learning during the first few

weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, 78.9% of faculty, 77.4% of master's students,

and 66.9% of medical students reported a positive view of the pandemic's impact. The attitudes

toward the impact of the shift to online education during the COVID-19 pandemic by position

are presented in Figure 2. Most respondents (76%) intended to integrate online expertise

gained during the COVID-19 pandemic into their teaching/learning strategies. The views on

willingness to integrate online expertise garnered during the COVID-19 pandemic into practice

are presented in Table 4.

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 6 of 11

FIGURE 2: Impact of the shift to online education during the

COVID-19 pandemic by position

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

Views N (%)

Agree 158 (76.0)

Disagree 31 (14.9)

No opinion 19 (9.1)

TABLE 4: Willingness to integrate online expertise garnered during the COVID-19

pandemic into practice

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

The study survey also solicited participants’ feedback regarding their experience in online

education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the comments were in support of either

online or blended instruction. Interestingly, most of the faculty were in favor of switching to

online teaching. A participant commented that the conditions created by the COVID-19

pandemic proved the effectiveness of online learning. Others reported additional advantages to

online learning during the pandemic, including the promotion of self-discipline and

responsibility.

Similarly, master’s and medical students gave positive feedback regarding online teaching and

even suggested a post-pandemic blended strategy. They believed that online instruction is

superior to face-to-face instruction. However, some medical students reported negative

experiences with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. They believed that online

education is not suitable for medical students. Others said that online teaching requires

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 7 of 11

extensive training and cannot be adopted over a short period.

Discussion

We are currently going through an unprecedented academic crisis. COVID-19 has shaken the

foundation of our society. Universities and colleges worldwide have been closed, and online

education has suddenly become an academic norm. Under these circumstances, educators and

students may find the rapid transition to online instruction distracting and frustrating. Based

on previous experiences, experts have predicted that it might take 5-10 years to recover from

this pandemic [10].

A reasonable number of faculty, master’s students, and medical students responded to our

survey during a healthcare crisis. Faculty and students participated in this timely study to

ensure that their voices are heard. A recent study has revealed that medical students are

interested in being part of the decision-making process relating to issues that may impact their

education [11]. Thus, it is prudent to engage faculty and students in the process of revamping

education for a challenging time. Nonetheless, the low response rate of the medical students

was anticipated since medical students were stressed out trying to adapt to new ways of

learning in the middle of a pandemic.

Most of the study respondents belonged to the Millennial or Post-Millennial generations. Both

generations are social-media savvy; social media is their primary source of communication

[18]. This fact may partly explain the acceptance of online teaching and learning by most study

respondents. Moreover, most of the present study respondents preferred combining online with

face-to-face instruction. Similarly, previous studies have reported that hybrid learning is

becoming more accepted among academic communities because it combines “the best of both

worlds” [1]. However, the effectiveness of hybrid learning depends on several factors, mainly

adequate faculty training and institutional support [19].

In the present study, the primary challenge to online education at COM as reported by the

respondents was related to communication. Faculty and students have quickly learned

that clear and concise feedback is essential when switching over to a virtual environment

during a healthcare crisis. This opportunity to improve ways of communication between faculty

and students during COVID-19 could enhance communication in traditional face-to-face

courses as well. Other challenges were related to student’s online assessment, access to

computer hardware or software, and other technical barriers, the scarcity of experience with

online education, pandemic-related anxiety, and technophobia. These challenges were akin to

those faced in the transition to online education during non-emergency situations [11,13,9]. In

the present study of highly educated subjects, technophobia was the least reported challenge.

Technophobia, the fear of using technological tools like computers, was correlated with users’

education [12]. Identifying these challenges may assist in recognizing online teaching and

learning practices that can enhance classes even when we return to conventional face-to-face

instruction.

During the current healthcare crisis, when the COM faculty and students are faced with the

uncertainties regarding remote instruction, close to half of the respondents stated they felt a

level of anxiety about how well the semester would go. They reported reaching out to their

campus colleagues, administrators, librarians, and information technology (IT) personnel to

assist in the transition to online education. Besides, faculty members also reported the need to

re-examine their teaching practices. Study respondents also emphasized the need to draw on

research to guide the institution and the academic community in times of healthcare crisis,

especially at a research-based institution like the Alfaisal University.

Despite these challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a positive impact on the faculty and

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 8 of 11

students’ acceptance of online education. Specifically, 67% of the medical students reported a

positive impact of the pandemic on online learning. In a recent survey of more than 400 college

students whose schools had recently switched over to online education due to the COVID-19

pandemic, 60% of students reported being somewhat prepared for the switch [20]. Also, most of

the study participants envisioned integrating expertise garnered during the pandemic into their

future teaching/learning strategies. However, integrating the skills required for online teaching

into practice requires adequate faculty professional development [10].

Most of the faculty feedback supported online teaching; good teaching is good teaching,

whether it is face-to-face or in a virtual environment. Some of the faculty were satisfied with

online teaching despite using teaching methods they had never tried before. Other faculty

commented that the COVID-19 pandemic proved the efficacy of online education. Other

comments praised the support from the institution during the pandemic, especially regarding

making resources available and real-time support services using multiple channels of

communication.

However, the students’ comments varied. Some students praised blended education since it

removed some of the traditional teaching barriers that do not work for all students. Schools can

tailor the learning experience for each student with access to current technologies and the

availability of resources. Students also believed that the quality of instruction has not suffered

in the shift to an online environment. Others reported that the first few online sessions were

problematic. Faculty and students had to adjust to the online environment. Other students

were unhappy with the online learning experience. They wanted to return to conventional face-

to-face education right after the pandemic.

The study had several limitations. We conducted the study during the first phase of the COVID-

19 pandemic at a private institution where most students are financially secure. Besides, the

study did not gather information about the needs of students with disabilities during the

transition to online courses. Moreover, we did not record students’ grade point average (GPA),

as the GPA might have been a modifier of responses. Finally, there are many online universities,

but we typically do not value their degrees as highly as those provided by brick-and-mortar

universities. Hence, medical faculty and students tend to support the blended experience to a

much greater extent than an entirely online one. Consequently, the study may have limited

generalizability [21]. Despite these limitations, we believe the study provides relevant insights

into the challenges facing online medical education in a time of healthcare crisis.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that there has been a positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online

medical education at Alfaisal University. Challenges brought about by the pandemic included

those related to communication, student assessment, use of technology tools, online

experience, pandemic-related anxiety or stress, time management, and technophobia. Despite

these challenges, the experience respondents have had during the first few weeks of the

pandemic has increased their confidence in the effectiveness of online medical education.

While pandemics have historically created challenges, identifying these challenges is the first

step in converting them into opportunities. One of the chief opportunities is to engage medical

students and faculty in transforming the current pandemic-imposed remote medical education

into an evidence-based paradigm. However, the study poses more questions than answers. For

example, has the conventional medical education, as we know it, changed forever, and is online

learning the future of medical education?

Additional Information

Disclosures

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 9 of 11

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Alfaisal University

Institutional Review Board issued approval IRB-20027. This study was approved by the Alfaisal

University Institutional Review Board with the approval number IRB-20027. Animal subjects:

All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue. Conflicts

of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the

following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was

received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors

have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three

years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other

relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that

could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Orlearns M: Cases on Critical And Qualitative Perspectives in Online Higher Education .

DeMarco A, Wolfe K (ed): IGI Global, Hershey, PA; 2014.

2. Edginton A, Holbrook J: A blended learning approach to teaching basic pharmacokinetics and

the significance of face-to-face interaction. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010, 74:88. 10.5688/aj740588

3. Hixon E, Buckenmeyer J, Barczyk C, Feldman L, Zamojski H: Beyond the early adopters of

online instruction: motivating the reluctant majority. Internet High Educ. 2012, 15:102-107.

10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.005

4. CDC: coronavirus (COVID-19) . (2020). Accessed: April 15, 2020:

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

5. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 . (2020).

Accessed: March 22, 2020: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-

opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-....

6. WHO: what is a pandemic? . (2010). Accessed: March 11, 2020:

https://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/frequently_asked_questions/pandemic/en/.

7. 'Panic-gogy': teaching online classes during the coronavirus pandemic . (2020). Accessed:

March 20, 2020: https://www.npr.org/2020/03/19/817885991/panic-gogy-teaching-online-

classes-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic.

8. Will shift to remote teaching be boon or bane for online learning? . (2020). Accessed: March

19, 2020: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/03/18/most-

teaching-going-remote-will-help-or-hurt-onlin....

9. Esani M: Moving from face-to-face to online teaching . Clin Lab Sci. 2010, 23:187-190.

10.29074/ascls.23.3.187

10. How does the pandemic affect U.S. college students? Temple University, Philadelphia. CNN

interview. (2020). Accessed: April 2, 2020: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/amanpour-and-

company/video/how-does-pandemic-affect-low-income-students-nufk5j/.

11. Rajab MH, Gazal AM, Alkawi M, Kuhail K, Jabri F, Alshehri FA: Eligibility of medical students

to serve as principal investigator: an evidence-based approach. Cureus. 2020, 12:e7025.

10.7759/cureus.7025

12. Nimrod G: Technophobia among older Internet users. Educ Gerontol. 2018, 44:148-162.

10.1080/03601277.2018.1428145

13. Rosen LD, Weil MM: Computer availability, computer experience and technophobia among

public school teachers. Comput Hum Behav. 1995, 11:9-31. 10.1016/0747-5632(94)00018-D

14. Chiasson K, Terras K, Smart K: Faculty perceptions of moving a face-to-face course to online

instruction. J Coll Teach. 2015, 12:321. 10.19030/tlc.v12i3.9315

15. Embracing online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic . (2020). Accessed: April 22, 2020:

https://www.ecampusnews.com/2020/03/17/embracing-online-teaching-during-the-covid-

19-pandemic..

16. Lion RW, Stark G: A glance at institutional support for faculty teaching in an online learning

environment. EDUCAUSE Quarterly. 2010, 33:3.

17. Rajab MH: A Master of public health with a concentration in mass gatherings health . Cureus.

2019, 11:e5944. 10.7759/cureus.5944

18. Defining generations: where millennials end and Generation Z begins . (2019). Accessed:

March 18, 2020: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 10 of 11

and-generation-z-begins/ .

19. Comas-Quinn A: Learning to teach online or learning to become an online teacher: an

exploration of teachers’ experiences in a blended learning course. ReCALL. 2011, 23:218-232.

10.1017/S0958344011000152

20. Tackle challenges of online classes due to COVID-19 . (2020). Accessed: May 9, 2020:

https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/how-to-overcome-challenges-of-

online-classes-due-to-coronavirus.

21. Kukull WA, Ganguli M: Generalizability: the trees, the forest, and the low-hanging fruit .

Neurology. 2012, 78:1886-1891. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f812

2020 Rajab et al. Cureus 12(7): e8966. DOI 10.7759/cureus.8966 11 of 11

You might also like

- COVID-19: Impact on Education and BeyondFrom EverandCOVID-19: Impact on Education and BeyondNivedita Das KunduRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (5)

- 2 Adaptation and Perception Online TechnologyDocument4 pages2 Adaptation and Perception Online Technologyhamroprint1000No ratings yet

- Closure of Universities Due To Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) : Impact On Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic StaffDocument6 pagesClosure of Universities Due To Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) : Impact On Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staffhanifah ratna biranaNo ratings yet

- 3 Adaptation - To - Online - Technology - For - Learning - DurinDocument5 pages3 Adaptation - To - Online - Technology - For - Learning - Durinhamroprint1000No ratings yet

- During COVID-19 OnlineHigherEducationDocument7 pagesDuring COVID-19 OnlineHigherEducationAmmer Yaser MehetanNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Students' Perception and Satisfaction Regarding Online Learning System Amidst Covid-19 Pandemic in PakistanDocument7 pagesUndergraduate Students' Perception and Satisfaction Regarding Online Learning System Amidst Covid-19 Pandemic in Pakistanعمر أميرNo ratings yet

- The Experiences, Challenges, and Acceptance of E-Learning As A Tool For Teaching During The COVID-19 Pandemic Among University Medical StaffDocument12 pagesThe Experiences, Challenges, and Acceptance of E-Learning As A Tool For Teaching During The COVID-19 Pandemic Among University Medical Staffyoan corniusella dewiNo ratings yet

- I. Research TitleDocument10 pagesI. Research TitleSantiano ShaneNo ratings yet

- Pillos-Stem K (B)Document3 pagesPillos-Stem K (B)Christian Paul A. AsicoNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 13 02546 v2Document20 pagesSustainability 13 02546 v2Ajay LakshmananNo ratings yet

- Sahu 2020 Closure of Universities Due To CoroDocument5 pagesSahu 2020 Closure of Universities Due To CoroariefrafsanjaniNo ratings yet

- Online Learning Amongst University of Nairobi Undergraduate Students Amid Covid-19 Pandemic, KenyaDocument23 pagesOnline Learning Amongst University of Nairobi Undergraduate Students Amid Covid-19 Pandemic, KenyaGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Task 4 by AbimbolaDocument6 pagesTask 4 by AbimbolaMOHAMMED ALFATIHNo ratings yet

- Journal of Taibah University Medical SciencesDocument2 pagesJournal of Taibah University Medical Sciencesعمر أميرNo ratings yet

- Senior High School Faculty, Divine Word College of Legazpi, PhilippinesDocument8 pagesSenior High School Faculty, Divine Word College of Legazpi, PhilippinessilvacastilloangelieNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review of Effect of Online Classes On Mental Health This PandemicDocument14 pagesA Literature Review of Effect of Online Classes On Mental Health This PandemicDale Ros Collamat100% (1)

- Sahu PK 2000 Cureus PDFDocument7 pagesSahu PK 2000 Cureus PDFAnand AanuNo ratings yet

- E-LEARNING DURING CoVID-19A REVIEW OF LITERATUREDocument25 pagesE-LEARNING DURING CoVID-19A REVIEW OF LITERATUREbkt7No ratings yet

- Ubi20402 Draft Academic Essay Outline AssessmentDocument4 pagesUbi20402 Draft Academic Essay Outline AssessmentIda Sofya Shuhada Binti Ab.Rashid G20A0256No ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of The Benefits and Challenges of Mobile Learning During The COVID19 PandemicDocument14 pagesA Systematic Review of The Benefits and Challenges of Mobile Learning During The COVID19 PandemicCatur Haanii AlfathinNo ratings yet

- Pendidikan Kedokteran Di Masa Pnademi COVID-19Document9 pagesPendidikan Kedokteran Di Masa Pnademi COVID-19Aisyah FawNo ratings yet

- Pendidikan Kedokteran Di Masa Pandemi COVID-19 Dampak Pembelajaran Daring Bagi Mahasiswa Fakultas Kedokteran Angkatan 2017 UnsratDocument11 pagesPendidikan Kedokteran Di Masa Pandemi COVID-19 Dampak Pembelajaran Daring Bagi Mahasiswa Fakultas Kedokteran Angkatan 2017 UnsratAisyah FawNo ratings yet

- Repercussions of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Moroccan Medical Students EducationDocument3 pagesRepercussions of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Moroccan Medical Students EducationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Educational Research OpenDocument25 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Educational Research OpenRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Examining Learning Experience and Satisfaction of Accounting Students in Higher Education Before and Amid COVID-19Document12 pagesExamining Learning Experience and Satisfaction of Accounting Students in Higher Education Before and Amid COVID-19Angelica Mae MarquezNo ratings yet

- Effect of The Pandemic On The Knowledge and Skills of Level III Nursing Students of ADZUDocument20 pagesEffect of The Pandemic On The Knowledge and Skills of Level III Nursing Students of ADZUJosh MagistradoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1110016821007171 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S1110016821007171 MainPaula AdoraNo ratings yet

- New Covid FormatDocument30 pagesNew Covid Formatasmahdental1No ratings yet

- The Effect of Covid 19 Pandemic in The Learning of Bsit Student in Colegio de Montalban 2021Document3 pagesThe Effect of Covid 19 Pandemic in The Learning of Bsit Student in Colegio de Montalban 2021Ron AguilarNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities For Higher Education Amid The COVID19 PandemicDocument5 pagesChallenges and Opportunities For Higher Education Amid The COVID19 PandemicYou TubeNo ratings yet

- Online Teaching and Learning of Higher Education in India During COVID-19 Emergency LockdownDocument14 pagesOnline Teaching and Learning of Higher Education in India During COVID-19 Emergency LockdownManjunath PatelNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature 1Document3 pagesReview of Related Literature 1Joylene Dayao DayritNo ratings yet

- Cche 690 Staement PaperDocument9 pagesCche 690 Staement Paperapi-592697594No ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 10556 v2Document10 pagesIjerph 19 10556 v2franceseunyNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Students Readiness For E-Learning - Dehghan 2022 GOODDocument5 pagesAssessing The Students Readiness For E-Learning - Dehghan 2022 GOODDiah Royani MeisaniNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 2811Document7 pages2021 Article 2811Anggoro OctaNo ratings yet

- Introduction - Siska PebrianiDocument2 pagesIntroduction - Siska PebrianiYuan NaozomiNo ratings yet

- Online Learning Challenges and Coping Mechanisms of The Students in A Private Catholic InstitutionDocument16 pagesOnline Learning Challenges and Coping Mechanisms of The Students in A Private Catholic InstitutionPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- The Impact of COVID-19 On The Undergraduate Medical CurriculumDocument3 pagesThe Impact of COVID-19 On The Undergraduate Medical CurriculumMatta KongNo ratings yet

- Covid 19 Pandemic and Online Learning The Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument14 pagesCovid 19 Pandemic and Online Learning The Challenges and OpportunitiesSyed Shafqat Shah67% (3)

- From Lockdown' To Letdown: Students' Perception of E-Learning Amid The Covid-19 Outbreak Kriswanda KrishnapatriaDocument8 pagesFrom Lockdown' To Letdown: Students' Perception of E-Learning Amid The Covid-19 Outbreak Kriswanda Krishnapatriaenne zacariasNo ratings yet

- The Review of Related LiteratureDocument6 pagesThe Review of Related LiteratureIsellah EllenNo ratings yet

- Research PapersDocument14 pagesResearch PapersFrancine OardeNo ratings yet

- Distance Learning in Clinical MedicalDocument7 pagesDistance Learning in Clinical MedicalGeraldine Junchaya CastillaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic On The Academic Performance of Veterinary Medical StudentsDocument10 pagesThe Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic On The Academic Performance of Veterinary Medical StudentsRoan Matthew Javier OcampoNo ratings yet

- AbuTalib2021 Article AnalyticalStudyOnTheImpactOfTeDocument28 pagesAbuTalib2021 Article AnalyticalStudyOnTheImpactOfTenanthini kanasanNo ratings yet

- Written Task-Research ArticleDocument8 pagesWritten Task-Research ArticleMark ZalsosNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities For Higher Education Amid The COVID-19 Pandemic: The Philippine ContextDocument6 pagesChallenges and Opportunities For Higher Education Amid The COVID-19 Pandemic: The Philippine ContextMae Anne Yabut Roque-CunananNo ratings yet

- The Impact of CovidDocument8 pagesThe Impact of CovidMark ZalsosNo ratings yet

- Academic Experiences, Physical and Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic On Students and Lecturers in Health Care EducationDocument13 pagesAcademic Experiences, Physical and Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic On Students and Lecturers in Health Care Educationluis renzoNo ratings yet

- NURSING - Online Learning Methods During COVID-19 Pandemic On An Indonesian Nursing Student ExperienceDocument7 pagesNURSING - Online Learning Methods During COVID-19 Pandemic On An Indonesian Nursing Student Experiencenayla.vtcNo ratings yet

- A Study On Imapct of Covid 19 On Indian Education System - Neha Nupoor, Kaishlay Kumar & Dr. Sandeep KumarDocument11 pagesA Study On Imapct of Covid 19 On Indian Education System - Neha Nupoor, Kaishlay Kumar & Dr. Sandeep KumarStella StellaNo ratings yet

- Online Learning During The COVID-19 Pandemic and Academic Stress in University StudentsDocument9 pagesOnline Learning During The COVID-19 Pandemic and Academic Stress in University StudentsIntan Delia Puspita SariNo ratings yet

- 15-11-2022-1668515243-8-IJHSS-24. Sustainability of The Acceleration in Edtech Growth Post COVID - 1 - 1 - 1Document14 pages15-11-2022-1668515243-8-IJHSS-24. Sustainability of The Acceleration in Edtech Growth Post COVID - 1 - 1 - 1iaset123No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - 3Document30 pagesChapter 1 - 3ajani waleNo ratings yet

- Impact of Pandemic On STEM (: Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics)Document9 pagesImpact of Pandemic On STEM (: Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics)Charles Jandrei PereyraNo ratings yet

- Online Learning: A Panacea in The Time of COVID-19 Crisis: Shivangi DhawanDocument18 pagesOnline Learning: A Panacea in The Time of COVID-19 Crisis: Shivangi Dhawanjames chhetriNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proofs: Children and Youth Services ReviewDocument21 pagesJournal Pre-Proofs: Children and Youth Services Reviewhymen busterNo ratings yet

- (Coded) 15 Nursing Students - and Faculty Members - Perspectives About Online Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic A Qualitative StudyDocument7 pages(Coded) 15 Nursing Students - and Faculty Members - Perspectives About Online Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic A Qualitative StudyAngus LiuNo ratings yet

- RRL Mental Health Adjustment and Perceived Academic Performance of Senior Highschool StudentsDocument22 pagesRRL Mental Health Adjustment and Perceived Academic Performance of Senior Highschool StudentsNur SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Project Zia SBDocument17 pagesProject Zia SBZeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document11 pagesAssignment 1Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Operation On FunctionsDocument45 pagesOperation On FunctionsZeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3Document10 pagesAssignment 3Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- English Assignment 2Document8 pagesEnglish Assignment 2Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Article Mazhar 07Document8 pagesArticle Mazhar 07Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Article Mazhar 20Document13 pagesArticle Mazhar 20Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- The Sudden Transition To Synchronized Online Learning During The COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study Exploring Medical Students ' PerspectivesDocument10 pagesThe Sudden Transition To Synchronized Online Learning During The COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study Exploring Medical Students ' PerspectivesZeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: Journal of Affective DisordersDocument27 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: Journal of Affective DisordersZeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Post-Covid-19 Education and Education Technology Solutionism': A Seller's MarketDocument16 pagesPost-Covid-19 Education and Education Technology Solutionism': A Seller's MarketZeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Artical Mazhar 6Document2 pagesArtical Mazhar 6Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Pandemic Designs For The Future: Perspectives of Technology Education Teachers During COVID-19Document13 pagesPandemic Designs For The Future: Perspectives of Technology Education Teachers During COVID-19Zeeshan KhanNo ratings yet

- Engineering Management (Final Exam)Document2 pagesEngineering Management (Final Exam)Efryl Ann de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- GR L-38338Document3 pagesGR L-38338James PerezNo ratings yet

- Sample Opposition To Motion To Strike Portions of Complaint in United States District CourtDocument2 pagesSample Opposition To Motion To Strike Portions of Complaint in United States District CourtStan Burman100% (1)

- Chapter 5Document3 pagesChapter 5Showki WaniNo ratings yet

- PC210 8M0Document8 pagesPC210 8M0Vamshidhar Reddy KundurNo ratings yet

- 90FF1DC58987 PDFDocument9 pages90FF1DC58987 PDFfanta tasfayeNo ratings yet

- CH 1 India Economy On The Eve of Independence QueDocument4 pagesCH 1 India Economy On The Eve of Independence QueDhruv SinghalNo ratings yet

- Reverse Engineering in Rapid PrototypeDocument15 pagesReverse Engineering in Rapid PrototypeChaubey Ajay67% (3)

- United Nations Economic and Social CouncilDocument3 pagesUnited Nations Economic and Social CouncilLuke SmithNo ratings yet

- TLE - IA - Carpentry Grades 7-10 CG 04.06.2014Document14 pagesTLE - IA - Carpentry Grades 7-10 CG 04.06.2014RickyJeciel100% (2)

- CDKR Web v0.2rcDocument3 pagesCDKR Web v0.2rcAGUSTIN SEVERINONo ratings yet

- Vinera Ewc1201Document16 pagesVinera Ewc1201josue1965No ratings yet

- Ts Us Global Products Accesories Supplies New Docs Accessories Supplies Catalog916cma - PDFDocument308 pagesTs Us Global Products Accesories Supplies New Docs Accessories Supplies Catalog916cma - PDFSRMPR CRMNo ratings yet

- My CoursesDocument108 pagesMy Coursesgyaniprasad49No ratings yet

- Rebar Coupler: Barlock S/CA-Series CouplersDocument1 pageRebar Coupler: Barlock S/CA-Series CouplersHamza AldaeefNo ratings yet

- Viceversa Tarot PDF 5Document1 pageViceversa Tarot PDF 5Kimberly Hill100% (1)

- SND Kod Dt2Document12 pagesSND Kod Dt2arturshenikNo ratings yet

- Datasheet Qsfp28 PAMDocument43 pagesDatasheet Qsfp28 PAMJonny TNo ratings yet

- A PDFDocument2 pagesA PDFKanimozhi CheranNo ratings yet

- BASUG School Fees For Indigene1Document3 pagesBASUG School Fees For Indigene1Ibrahim Aliyu GumelNo ratings yet

- Aluminum 3003-H112: Metal Nonferrous Metal Aluminum Alloy 3000 Series Aluminum AlloyDocument2 pagesAluminum 3003-H112: Metal Nonferrous Metal Aluminum Alloy 3000 Series Aluminum AlloyJoachim MausolfNo ratings yet

- 004-PA-16 Technosheet ICP2 LRDocument2 pages004-PA-16 Technosheet ICP2 LRHossam Mostafa100% (1)

- Aircraftdesigngroup PDFDocument1 pageAircraftdesigngroup PDFsugiNo ratings yet

- Peoria County Jail Booking Sheet For Oct. 7, 2016Document6 pagesPeoria County Jail Booking Sheet For Oct. 7, 2016Journal Star police documents50% (2)

- Labstan 1Document2 pagesLabstan 1Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Cryo EnginesDocument6 pagesCryo EnginesgdoninaNo ratings yet

- Supergrowth PDFDocument9 pagesSupergrowth PDFXavier Alexen AseronNo ratings yet

- Simoreg ErrorDocument30 pagesSimoreg Errorphth411No ratings yet

- Online EarningsDocument3 pagesOnline EarningsafzalalibahttiNo ratings yet

- Resume Jameel 22Document3 pagesResume Jameel 22sandeep sandyNo ratings yet