Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mediators and Mediation Strategies in International Relations

Uploaded by

Nithya GaneshOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mediators and Mediation Strategies in International Relations

Uploaded by

Nithya GaneshCopyright:

Available Formats

In Theory

Mediators and Mediation Strategies

in International Relations

Jacob Bercovitch

Conflict is an inescapable aspect of all interactions. This is true of interpersonal

interactions, as it is of intergroup or international interactions. Given the poten-

tiality of omnipresem com'~ct, a limited range of widely accepted conflict-

handling procedures in the international environment, and the unwelcome real-

ity of destructive conflict, it is hardly surprising that so many individuals, bod-

ies or oganizations that have significant influence and standing in. the global

community may be keen to do something to facilitate peaceful interactions.

What they can best do is offer their mediation services.1 Mediation is, after

all, a low-cost and flexible approach, a n approach that may be adopted legiti-

mately and creatively by private citizens, international organizations, and any

other actor whose behavior affects the dynamic, multi-level process that con-

stimtes international relations (as opposed to internationalpolitics). 2 The suc-

cessful application of mediation requires experience, professionalism, and

judgment of the Sort all international actors possess. Although it is a serious

and time-consttming undertaking, mediation rarely does more harm than good,

and more often than not it helps the cause of constructive conflict manage-

ment, as well as, let us not forget, the interests of the mediator.

In an environment lacking a centralized authorit3~, the range of poss~le

mediators is immense. In a way, any actor in the global environment may become

a formal or informal mediator. To make some sense of the bewildering range

of possible mediators and their behavior, I suggest that they are all encompassed

within any one of the following three categories of actors in international rela-

tions: individuals, states, and institutions and organizations.3 Following is a

description of the characteristics of each category of mediators.

I n d i v i d u a l s . The traditional image of International mediation, one nur-

tured by the media and popular accounts, is that of a single, usually- high-ranking,

J a c o b B e r c o v i t c h is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Canterbury in Christ-

church, New Zealand, He and Jeffrey Z. Rubin ate the editors of a forthcoming new book called

Mediation in International Relations (London: Macmillan and New York: St. Martin's Press).

0748-4526/92/0400-009956.50/0 © 1992 PlenumPublishingCorporation Negotiation Journal April 1992 99

individual, shuttling from one place to another trying to search for understand-

ing, restore communication between hostile parties, or help settle their con-

flict. This image is only partly accurate. The individual mediator w h o engages

in such behavior is normally an official representing his or her government

in a series of formal interactions with high-level officials from the disputing

countries. The interactions may be of an individual kind (as most political inter-

actions ultimately are), but we must not lose sight o f the fact that most o f these

individuals represent larger constituencies, n o r should we attempt to explain

complex political p h e n o m e n a in terms of the one easily visible component,

namely, the individual. For example, w h e n President Carter brought Prime

Minister Begin and President Sadat to Camp David, much face-to-face interac-

tion occurred, but no one could possibly describe the whole experience as

individual mediation. The three leaders were there as representatives of their

respective countries, with a highly developed sense of the consequences and

constraints o f representation.

By individual mediation I mean a process that is carried o n by individuals

w h o do not ft~lll an official, representative traction. Individual mediators may

differ with respect to the nature and level o f their capabilities and resources;

their ability to perform the tasks required; as well as their knowledge, skills,

experience, and other attributes. They may also hold different beliefs, values,

and attitudes. These qualities affect both the objectives they may seek and their

range of strategies in mediation. The strategies and mediation o f individuals

are more directly related to their capabilities and subjective experiences than

to the external and contextual stimuli that may impinge on them. Individual

mediation can, therefore, exhibit greater flexibility and experimentation than

mediation by political incumbents.

Individual mediation may be carried o n informally or formally. Informal

mediation refers to the efforts o f practitioners w h o have a long-standing

experience of, and a deep commitment to, international conflict resolution (e.g.,

the Quakers), or knowledgeable scholars whose background, attitudes, and

behavior may enable disputants to engage in productive conflict management

(e.g., the efforts of scholars such as Burton, Doob, and Kelman). 4 Such

individuals approach an international dispute as private citizens only, not as

official representatives, and their efforts are designed to utilize their compe-

tence, credibility, and experience to create contexts and occasions in which

communication may be facilitated and in which a better understanding o f a

conflict may be gained.

Formal mediation, o n the other hand, takes place w h e n a political incum-

bent, a government representative, or a high-level decision maker acts in an

individual capacity to mediate a dispute between the official representatives

of other groups or states. It invariably occurs within a formal structure (e.g.,

conference, political forum, or other official arena) and is less flexible than infor-

mal mediation. Formal mediation combines role and individual variables and

is thus less susceptible to the impact of personality characteristics. Its loss o f

flexibility, however, is more than matched by its immediacy o f access to high-

level and influential decision makers. Formal mediation usually takes place in

the diplomatic arena, within a structure that emphasizes f o r m , established proce-

dures, and roles. Its r a ~ e o f strategies may be m u c h more limited than that

o f informal mediation, but it does more directly affect political outcomes.

100 Jacob Bercovitch International Relations

States. Individual mediation, although significant, is not all that c o m m o n

in international relations. Most mediation activity is carried o n by states (or

to be more accurate, their representatives) and international or regional organi-

zations.

As a political actor, the state is one o f the most successful and enduring

forms o f social and political organization. As an organization, the state offers

a measure of political and economic security and in return expects the unquali-

fied allegiance of the people. Today, some 180 sovereign and legally equal states

- - but with different capabilities, regime-structures and interests - - interact in

the international arena. They pursue resources, markets, and influence. Often,

they get into conflicts with other states that are pursuing similar objectives.5

W h e n this happens, representatives of states get together in any of the myriad

of international forums to articulate their concerns and search for a settlement

m through mediation or other means.

Notwithstanding the increase in, and importance accorded to, v~trious trans-

national entities (e.g., multinational corporations, international organizations),

states are still widely regarded as the most significant actors in international

politics. The m o d e r n diplomatic system evolved around the state, and m a n y

o f the rudimentary norms and traditions o f behavior that are current in inter-

national relations pertain to states only. The vibrant patterns o f interplay and

shifting relationships that make up the international arena are dominated by

h o w states perceive events, evaluate them, and respond to them. One o f the

events to which states may have to respond is whether or not to accept or offer

mediation.

When a state is invited to mediate a dispute, or initiates such mediation

itself, it normally engages the services of one o f its top decision makers. Figtmes

such as Dr. Henry Kissinger, President Carter, Secretary o f State Baker, or Lord

Carrington fulfill a mediatory role, in the full glare o f the international media,

as salient representatives o f their countries. The activities o f these individuals

depend o n (a) the position they hold in their o w n country; (b) the leeway given

to them in determining policies; and (c) the different resottrces, capabilities,

and political orientations o f their countries.

Looking at differences between states, it is possible to draw distinctions

between aligned states and nonaligned states, democratic states and non-

democratic states, or economically developed and underdeveloped states. In

addition, it is also possible to focus on the p o w e r distinction between small

states and great powers and evaluate its significance for mediation. By using

the terms small states and large states, I do not mean to refer to the size o f

the state, per se, but to its "weight" in the international system. 6 Large states

are those states whose "weight" and resources significantly surpass those of

other states, and small states are those whose "weight" and resources are sig-

nificandy below those of other actors in the international system.

Representatives o f all states interact formally in the various international

policy-making bodies. But trying to penetrate b e y o n d the myth o f formal

representation and legal equality, it is legitimate to w o n d e r to what extent d o

tremendous differences in the level o f resources impinge o n the m a n n e r and

m e t h o d o f mediation, or indeed the choice o f disputes? Are such differences

significant, or ate they cancelled out by the formal context? I believe these differ-

ences are crucial to mediation success and should be examined in greater detail.

Negotiation Journal April 1992 101

We cannot assume that mediation by small states resembles, in every aspect,

the mediation efforts o f a large state.

Institutions a n d Organizations. The complexity o f the international

environment is such that states and nations can no longer facilitate the pursuit

o f human interests, nor satisfy their demands for an ever-increasing range o f

services. Consequently, we have witnessed a p h e n o m e n a l growth in the num-

ber o f international, transnational, and other nonstate actors, all of w h o m affect

issues of war and peace, knowledge and responsibility, and environment and

survival. These functional systems of activities or organizations have become,

in some cases, more important providers of services than states. They have also

become, in the m o d e r n international system, active participants in the search

for institutions and proposals conducive to peace. We would expect such organi-

zations to play their full part in the mediation of international disputes.

Three kinds o f organizations - - regional, international, and transnational

- - are important to our understanding o f international politics. Regional and

international organizations represent local or global collect_ions o f states sig-

nifying their intention to fulfill the obligations o f membership as set forth in

their formal treaty. Transnationat organizations represent individuals across

countries w h o have similar feelings, cognitions, knowledge, skills, or interests

w h o meet together o n a regular basis to promote the special interests o f their

members. Whereas regional and international organizations are "governmen-

tal" in origin, imbued with political purposes, and largely staffed by official

representatives, transnational organizations are "nongovernmental" in origin,

and insofar that they are not really "public" organizations, they can afford to

be more creative and less inhibited in the policy positions they advocate than

international organizations.

Regional, international and transnational organizations e m b o d y many o f

the elements c o m m o n l y associated with impartiality. They are also usually-

entrusted with the task of mediating disputes between members. Such bodies

may appear, o n the face of it, to be ideal mediators. In reality, alas, their role

and performance are circumscribed by the lack of an adequate resource base.

Mediation requires resources which regional, international, or transnational

organizations do not always possess.

Strategies and Behavior in International Mediation

With so many political actors capable o f initiating and conducting international

mediation, h o w can we even begin to make sense of the wide range o f media-

tion behavior and the many strategies that may be adopted? Is not the variabil-

ity o f actors - - from individuals to large states n and behavior too great to

permit any useful analysis? It may seem so intuitively, but it is not so in reality.

Proliferation of actors need not obscure the essence of international mediation.

We can have c o m m o n standards, build o n our existing knowledge, and develop

a model that accounts for the ways different mediators operate and explains

the reasons for such differences.

All international mediators operate within a system o f exchange and

influence. The parameters o f that system can be identified as the communica-

tion, experience, and expectations set by the disputing parties and by the

resources and interests o f the mediators. The interplay among these parameters

determines the nature and effectiveness o f mediation. Whatever else they do,

102 Jacob Bercovitch International Relations

mediators - - be the3~ individuals, states, or institutions - - h o p e to influence,

change, or m o d i f y o n e or m o r e o f these parameters. This is at the " h e a r t " o f

international mediation. This is the aspect of mediation w e must discern ff w e

are to improve the p e r f o r m a n c e and effectiveness of mediation.

Normally, we suggest a n u m b e r o f roles to describe what mediators do

and h o w they go about achieving their objective. Mediators' roles m a y be charac-

terized in a n u m b e r of ways, Jeffrey Rubin (1981: 3-43), for instance, offers a

comprehensive set of dichotomous roles and distinguishes b e t w e e n formal vs.

informal roles, individual vs. representative roles, invited vs. noninvited role,

advisory vs. directive roles, content vs. process roles, p e r m a n e n t vs. temporary

roles, and conflict resolution vs. conflict prevention roles. Stulberg (1981: 85-117),

writing in a more traditional vein, lists the following potential roles for a medi-

ator: a catalyst; an educator; a translator; a resource-expander; a bearer o f bad

news; an agent o f reality; and a scapegoat. Susskind and Crttickshank (1987),

w h o s e conception of mediation is that o f "assisted negotiation," introduce a

dynamic element into the discussion by identifying a n u m b e r o f other roles

(e.g., representation, inventing options, monitoring) and relating these to the

various stages of negotiation. Each role has its place in the lifecycle of a conflict.

Discussing mediator behavior in terms of preordained roles does not really

take us very far in our quest for a better understanding of h o w different inter-

national mediators behave and w h i c h factors shape theft behavior. Mediators'

roles, w h e n placed o n a spectrum ranging f r o m passive (e.g., facilitation) to

active (e.g., p r o m o t i o n of settlement ideas) involvement, can be seen only in

static and typological terms. In reality, mediators a d o p t one or m o r e roles and,

if necessary, change these in the course o f mediation. Gulliver (1979: 2 2 0 ) p u t s

it very well w h e n he states that "it is necessary to avoid an assumption of the

role o f the mediator, w h e t h e r in description or prescription. Dogmatic asser-

tions o f that kind, unfortunately not u n c o m m o n , are misleading and stultify

careful analysis."

The enactment o f a particular role or a set o f roles, and the a d o p t i o n o f

a passive or active srance~ does not so m u c h d e p e n d o n the mediator's deter-

m i n e d adherence to a prescribed notion o f "a r o l e " but o n the context of the

dispute and the interests and resources o f the mediator. This is as true o f inter-

personal mediation as it is of international mediation.

Role classification provides one dimension along which mediation behavior

can be categorized. The notion of mediation strategies offers another dimen-

sion. A mediation strategy is defined by Kolb (1983: 249) as "an overall plan,

approach or m e t h o d a mediator has for resolving a d i s p u t e . . . i t is the way the

mediator intends to manage the case, the parties, and the issue." H o w can we

identify the m o s t important strategies, and h o w do mediators choose a partic-

ular strategy?

A great deal has b e e n written about the strategies and tactics o f media-

tion. Mediation strategies have traditionally b e e n viewed as either content or

process strategies (see Bartunek, Benton, and Keys, 1975: 532-557). Content

strategies are designed to change the substantive content of the dispute (through

the use o f such. tactics as offering suggestions, encouraging concessionmaldng,

hlaposing deadlines, etc.), and process strategies are designed to affect the per-

ceptual dimension o f the dispute (by educating the parties, offering facilities

for Better communication, etc.). The distinction b e t w e e n content a n d process

Negotiation Journal April 1992 103

strategies corresponds roughly to Kochan and Jick's (1978: 209-238) distinc-

tion between contingent and noncontingent strategies.

Other ways of categorizing mediator strategies include Kolb's (1983a) deal-

making strategies (affecting the substance of a dispute) and orchestration strate-

gies (managing the interaction) and Stein's (1985: 331-347) incremental (seg-

menting a dispute into smaller issues) vs. comprehensive strategies (dealing with

all aspects of a dispute). Carnevale (1986: 41-56; 1986a: 251-269) suggests that

mediators may choose from among four fundamental strategies: integration

(searching for c o m m o n ground), pressing (reducing range of available alterna-

tives), compensation (enhancing attractiveness of some alternatives), and inac-

tion (which, in effect, means no mediation). Kressel (1972), in one of the most

widely used typologies, presents three general mediation strategies: reflexive

(discovering issues, facilitating better interactions), nondirective (producing a

favorable climate for mediation), and directive (promoting specific outcomes).

Touval and Zartman's (1985: 7-20; Zartman and Touval, 1985: 27-46) three-

fold classification of mediation strategies offers, I believe, the best taxonomy

for the student of international mediation. The principal strategies they iden-

tifT are: communication-facilitation; formulation; and maniptflation. The use

of these strategies, in the process of transforming a dyad into a triad, is designed

to change, affect, or modify aspects of the dispute or the nature of interaction

between the parties. Different international mediators rely on different strate-

gies in different disputes. Mediators tend to adapt their strategy to the nature

of the dispute and to their own resources.

The specific behavioral tactics these strategies may lead to are as follows:

Communication-Facilitation

• make contact with parties

• gain the trust and confidence of the parties

• arrange for interactions between the parties

• identify issues and interests

• clarify situation

• avoid taking sides

• develop a rapport with parties

• supply missing information

• develop a framework for understanding

• encourage meaningful communication

• offer positive evaluations

• allow the interests of all parties to be discussed

Formulation

• choose meetings site

• control pace and formafity of meetings

• control physical environment

• establish protocol

• suggest procedures

• highlight c o m m o n interests

• reduce tensions

• control timing

• deal with simple issues first

• structure agenda

• keep parties at the table

104 Jacob Bercovitch International Relations

® help parties save face

* keep process focused o n issues

Manipulation

* change parties' expectations

* take responsibility for concessions

* make substantive suggestions and proposals

® make parties aware of costs o f nonagreement

® supply and filter information

® suggest concessions parties can make

® help negotiators to undo a commitment

® reward party concessions

® help devise a framework for acceptable outcome

* change expectations

* press the parties to show flexibility

® promise resources or threaten withdrawal

® offer to verify compliance with agreement

H o w do international mediators decide which specific tactics to utilize?

H o w do they determine which strategy to articulate? To answer such questions

one must recognize the fact that mediators cannot choose any strategy they

wish, irrespective o f circumstances. International mediators function within a

system that is composed, as Wall (1981: 157-180) so convincingly demonstrates,

o f the disputing parties, their relationship, the mediator, a number o f concerned

audiences or constituencies, and other factors such as societal norms, political

institutions, and economic pressures. The relationships within that system are

relationships of exchange and influence: Each actor has interests and expecta-

tions, each acxor possesses resources, and each expects to receive some rewards

the mediator as well as the disputing parties. We can, if we so desire, focus

o n one aspect of the relationship (say the behavior o f a mediator) and prescribe

a wide variety o f innovative methods o f mediation and advise their applicabil-

ity to all kinds o f international disputes. Unless we take into account the con-

text of the dispute and the resources o f a mediator, such prescn'ptions will

amount to little more than wishful thinking.

For international mediation to be effective, it must reflect as well as affect

the wider conflict system. This is one reason w h y different mediators use differ-

ent approaches and emphasize different aspects. It is as simplistic as it is errone-

ous to regard mediation outcomes as being totally related to mediation processes

only. Processes and procedures, strategies and tactics are deduced from the broad

context in which a mediator operates. Mediation must not be analyzed or under-

stood in terms o f a simple cause-and-effect model in which a particular stt'ategy

invariably produces a desired outcome.

Mediation, in general, and international mediation, in particular, are not

merely driven by some exogenous input that can be applied uniformly and

indiscriminately to all disputes. Nor is mediation merely a set of rules, the rigid

pursuit o f which can affect or influence the parties. The relationship between

a mediator and the ,disputing parties is reciprocal. Exchange and influence in

mediation are thus bidirectional, not unidirectional.

The strategies and behavior o f international mediators are so very differ-

ent not merely because o f actor differences, but because o f differences in the

nature and context o f a dispute and the characteristics o f the parties involved.

Negotiation Journal April 1992 105

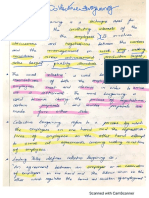

FIGURE 1

A F r a m e w o r k f o r the Analysis

o f Mediation Strategy and B e h a v i o r

Current Conditions Consequent

Antecedent Conditions (Mediation strategy & Conditions

(Prior to mediation) behavior) (Post-mediation)

Mediation

Identity & outcomes:

Nature of rank of (1) subjective

dispute mediator

(2) objective

i

Outcome

Mediation

Nature of strategy &

issues behavior

Process

Nature of

parties

Nature of

relationship

t

Context

1

~)6 jacob Bercovitch International 2~elatiom

To be effective, mediation strategy and behavior must match and reflect these

factors. The process (of mediation) and context (of a dispute) are closely inter-

related. The context factors influencing the choice and diversity o f mediators'

strategy and behavior can be placed in a general framework that organizes the

dimensions and processes of mediation into temporal sequences that depict

the interplay among prior conditions that are antecedent to mediation, the actual

process o f mediation, and subsequent outcomes.7

The structure and diversity of mediation in international relations may be

explained, in part, by the influence of different contexts. However, it is also

affected by the resources mediators can bring to bear o n the situation. An inter-

national mediator, whether an individual, a state, or an organization, is, after

all, an element that purports to influence, change, or affect a conflict system

that comprises an agent of influence (i.e., a mediator), the intended targets of

influence (i.e., the disputing parties), and the means of influence (i.e., media-

tor's resources), s To exert any influence at all, to change or affect aspects o f

an international dispute requires the possession or control of some valued

resources. What are these resources and to what extent do they determine medi-

ation behavior?

The control and possession of resources is a major determinant o f a medi-

ator's power to achieve a favourable outcome or other desired objectives.

Without resources, one cannot achieve any objective. In the context of a volun-

tary relationship such as mediation, these resources may take the form of oppor-

tunities, acts, and objects that can be used to effect a change in the behavior

or perceptions o f the disputing parties. Such resources may include money,

status, expertise, access, and prestige. The specific resources utilized in a par-

ticular instance depend u p o n the nature o f the mediator and the social context

o f mediation. Whichever form these resources take, and however they are

exploited, their use will affect mediation strategy and behavior as well as the

course and likely outcomes of mediation.

Mediators' resources constitute the basis required for exercising "leverage,"

or any other type of influence. Using the conceptualization of social influence

proposed originally by French and Raven (1959: 150-167), and modified by

Raven (1990: 493-520) more than 30 years later, six types of resources, or "bases

of p o w e r " may be identified. These are: reward, coercion, referent, legitimacy,

expertise, and information. Reward resources are based o n the mediator's abil-

ity to offer the parties tangible benefits and promises o f approval. Coercive

resources depend on various kinds of mediator's threats (e.g., the threat to with-

draw mediation or make public the recalcitrance of one or both parties). Referent

resources stem from a sense of mutual identity between a mediator and the

disputing parties and the desire to see things similarly. Legitimacy resources

are related the parties' internalized values that a mediator has a right and an

obligation (by virtue of occupying an office or a position) to change or influence

a dispute. Resources o f expertise depend on the disputants' belief that a medi-

ator does have superior knowledge and ability (because o f experience, train-

ing, or reputation) and really knows what is best. And informational resources

are based o n the mediator's ability to uncover and transmit valued information

that may lead to a change in some aspects o f the dispute.

This six-fold conception of resources provides the link among the media-

tor, the disputing parties, and the process o f mediation. If mediators wish to

Negotiation Journal April 1992 107

influence a dispute, they have to rely o n their resources to induce a change

in motivation, perception or behavior. One of m y central assumptions here is

that the choice o f resources, and thereby strategies, in mediation is not ran-

dom. Different mediators possess different resources and make use of t h e m in

different disputes. The possession and control of resources is in m a n y ways

the ticket to a specific f o r m of international mediation.

The motivation to change or influence and the expectation of goal-

achievement are the very reasons w h y so m a n y international actors are keen

to mediate. These actors rely o n different resources. Individual mediators, pos-

sessing only referent, legitimacy, and informational resources, show a strong

tendency to use communication-facilitative strategies. Institutions and organi-

zations are endowed with resources of legitimacy and expertise, and their medi-

ation strategies are mostly of the communicational and procedural kind. And

states, with so m a n y resources at their disposal, can use commtmicational,

procedural, and manipulative strategies. If mediation is about changing or

influencing a dispute or the disputants - - which, of course, it is - - then the

possession and use of different resources can be postulated to account for differ-

ences in mediation behavior.

We are often told that, to be successful, a mediator must take into account

the parties' needs, interests, and capabilities. To gain a better understanding of

mediation, we must k n o w something about the context of interactions, and

the needs, interests, and capabilities of the mediator. Shifting the focus from

the disputants to the mediator may seem a pretty obvious point, but it is,

nonetheless, one we have neglected for far too long.

Evaluating International Mediation

All international mediators, using their skills and resources, try to change or

influence the nature o f the parties' interactions, aspects of its context, and

the likely range o f outcomes. But h o w can the activities a n d contributions

o f so m a n y different mediators be assessed? H o w can the i m p a c t o f a partic-

ular mediation be evaluated? If mediation is ultimately about changing, affect-

ing, or influencing the nature of a dispute or the w a y the parties interact,

can such change even be discerned? Furthermore, if change has b e e n effected,

a n d a satisfactory o u t c o m e o f sorts has b e e n achieved, can this be attributed

to the w i s d o m and e x p e r i e n c e o f a mediator? And conversely, if the disput-

ing parties s h o w no change whatsoever, should this b e described as media-

tion failure? Evaluating the consequences of mediation and attributing success

or failure to one element, out of several interdependent elements, in a volun-

tary system o f interactions, poses serious c o n c e p t u a l and m e t h o d o l o g i c a l

problems.

As international mediation is not uniform, it seems futile to draw up one

set o f criteria to cover the varied objectives of all mediators. Individual media-

tots, for instance, may emphasize commtmicational-facilitative strategies, be more

concerned with the quality of interaction, and seek to be instrumental in creating

a better environment for negotiations. Mediating states, on the other hand, m a y

well seek to effect a change in the behavior of the parties and contribute toward

an appropriate settlement of the dispute. Such different objectives cannot be

easily a c c o m m o d a t e d within a single perspective. To answer the question

w h e t h e r or not mediation works, we need to k n o w something about the goals

lOB Jacob Bercovitch International Relations

of mediation. This is w h y I suggest the n e e d for two broad evaluative criteria,

subjective and objective, to assess the contribution and consequences of inter-

national mediation.

Subjective criteria - - and I use the term subjective because these criteria

can not usually be assessed empirically - - refer to the parties', or the media-

tor's, perception that the goals of mediation were achieved or that a desired

change took place. The goals o f mediation or the desired change pertain to

either the process of interaction or its outcome. Using this perspective, w e can

evaluate mediation as being successful w h e n the parties express satisfaction with

the process or o u t c o m e o f mediation, w h i c h they have perceived to be fair,

efficient, or effective.

Parties' satisfaction with mediation is generally high (see Latour and others,

1976: 319-356), but its precise meaning, let alone its measurement, is unclear.

Parties in dispute may express satisfaction with mediation because (a) the process

of mediation allows them a final say over the outcome or because (b) of the

intrinsic nature of mediation services rendered. Here, again, we cannot disen-

tangle one set o f perceptions from another. Nor can we l~md any evidence to

suggest that the overall level of satisfaction with international mediation is strongly

associated with particular kinds of mediators or certain strategies of mediation.

Fairness, or parties' conceptions o f entitlements and distribution of

resources~ defines another criterion in the evaluation of mediation outcomes.

Fairness can be thought of in terms of the parties' expressions of c o n c e r n with

the process of mediation or its outcome.9 As a process, international media-

tion is likely to be seen as fair w h e n it is " o p e n to continuous modification

by the disputants", (Susskind and Cruikshank, 1987: 21) and w h e n the media-

tor treats both parties equally. A mediated o u t c o m e is seen as fair w h e n the

parties' expectations are met, or w h e n the allocation of scarce resources is con-

sistent with the principles of equality, equity, or need.

The third subjective criterion for assessing mediation outcomes is efficiency

the time mediation takes and the costs to those involved. International medi-

ation that emphasizes timeliness, minimizes costs, and produces outcomes that

ma~dmize the benefits each party experiences m a y very well be evaluated as

successfftl mediation. There is no doubt that some international mediators con-

sider efficiency of procedures to be their p a r a m o u n t objective.

The final subjective criterion is effectiveness - - a key attribute o f a g o o d

outcome. This refers to the implementability and p e r m a n e n c e of a setdement.

An effectively mediated o u t c o m e is a stable and realistic o u t c o m e and one that

offers opportunities to avoid similar disputes in the future. Clearly, effective-

ness is a significant criterion in determining the success or failure o f media-

tion, but like the other criteria, it can be discerned only in hindsight - - and

even then, only in a totally subjective manner. Evaluating international media-

tion in terms o f its quality or expectations takes us s o m e way, albeit along a

fairly problematic road, toward analyzing the success or failure of various medi-

ation efforts.

Objective criteria offer a totally different perspective for evaluating media-

tion outcomes. Objective criteria rely o n substantive indicators that m a y be

assessed empirically by an observer or any o f the participants in mediation.

Usually, such criteria involve notions o f change and judgments about the extent

o f change as evidence of the success or failure of mediation.

Negotiation Journal April 1992 109

Objective criteria permit us to examine the behavior of the parties u p o n

the termination of mediation and to determine the extem o f change t h a t had

taken place. Thus, we can assess a particular mediation effort as having failed

if the parties continue to interact in the same dysfunctional manner. We can

see mediation as partly successful if its efforts contribute to a cessation of vio-

lent behavior and the opening o f dialogue between the parties. And w h e n the

parties embrace a formal outcome that settles many o f the issues in dispute

and produces new and more productive interactions, we can evaluate media-

tion as having been successful.

Evaluating international mediation in terms of observed change in the par-

ties' behavior is a relatively straightforward task. Using an objective criterion

to define the success or failure of mediation facilitates comparative evaluations

and permits systematic empirical research. On the surface, it does not suffer

from the arbitrariness and methodological problems that beset subjective criteria.

We would, however, be unwise to rely solely on objective criteria. Differ-

ent mediators, and indeed different conflict parties, have different goals in mind

w h e n they enter conflict management. Changing behavior could well be only

one among a set o f goals. Some international mediators may focus on the con-

tent of interactions; others may focus o n its climat~ setting, and decision-making

norms. These cannot always be easily evaluated. Each mediation should,

perhaps, be evaluated in terms of the criteria that are significant to its o w n

efforts. The questions of whether mediations work and h o w best to evaluate

them can be answered only by collecting information and making judgments

in specific cases. There are just too many problems with these questions, and

it seems that on this issue, our theoretical ambitions must be tempered by the

constraints of a complex reality.

Conclusion

Mediation has been, and remains, one o f the most significant methods o f con-

flict management. Mediators have played an important role in the attempts to

settle interpersonal or other conflicts from earliest times. Nowhere was this

role more visible than in the international arena, where mediation became quite

indistinguishable from the evolving pattern of diplomacy and the codification

o f international norms. Increased utilization has resulted in a greater need to

understand the p h e n o m e n o n of international mediation. It was with this in

mind that this article addressed one or two broad questions concerning medi-

ators' identity and their choice o f strategy.

International mediators operate in a complex arena of interdependent rela-

tions. They enter that arena in order to influence, change, or modify some of

its aspects. This is w h y mediation takes place. The best way to understand the

objectives and performance o f mediation is to analyze the c o m m o n dimen-

sions o f any interaction - - namely, actors, interests, resources, and behavior.

Many actors may initiate mediation. These actors have different interests, they

possess different resources, and their behavior is affected by their interests and

resources. The structure o f international mediation, and its diversity, is largely

explained by reference to these f o u r dimensions.

Improvements in international mediation will not necessarily come about

by fbcusing o n one dimension oniy and devising new inputs to inject at all

societal levels. More likely, they will come about by recognizing, as Thucydides

1tO Jacob Bercovitch International Relations

did more than two thousand years ago, that political p h e n o m e n a are due to

the interplay of person and circumstance, Likewise, mediators must be evalu-

ated in their contexts - - the actor and the structure. We need to keep both

sides of tl~s equation in mind if we are to understand the structure and diver-

sity o f mediation in international relations.

NOTES

This article is a revised version of Chapter One of the author's forthcoming book edited with

Jeffrey Z. Rubin, Mediation in International Relations (London: Macmillan and New York:

St• Martin's Press, 1992). Special thanks are due to Bill Breslin for his helpful comments and

suggestions.

1. On the range of providers of mediation services, see Kriesberg, 1991: 19-27.

2. The term relations is much broader than the term politics, which may be taken to apply

to official policy-making bodies only. We are interested here in the full range of interactions, not

merely official interactions. For a discussion of relations vs. politics, see Saunders, 1991: 41-69.

3. I am using the categories suggested, in a different context, by Waltz, 1959.

4. The efforts of these individuals have been the subject of a voluminous literature. Much

of it is summarized in Bercovitch, I984; Azar, 1990; Hill, 1982: 109-138; Kelman, 1972: 168-204;

and de Reuck, 1983: 27-36.

5. On the relation between states and conflict, see Rasler and Thompson, 1989.

6. Five factors can be identified as affecting the "weight" of a state: (a) population and terri-

tory; (b) military strength; (c) economic development; (d) level of industrialization; and (e) GNP

per capita.

7. This framework owes much to Drnckman's (1977) detailed analysis of negotiation. Also

see Bercovitch, 1984a: t25-144.

8. For a comprehensive review of this conception, see Tedeschi, Bonoma, and Scblenker,

1972: 346-418.

9. The discussion of procedural and outcome fairness owes much to Thibaut and Walker,

1975; and to Sheppard, 1984: 141-190.

REFERENCES

Azar, E. (1990). The management of protracted social conflict. Hampshire, England: Dartmouth.

B a r t u n e k , J., B e n t o n , A., and Keys, C. (1975). "Third party intervention and the bargaining

behavior of group representatives." Journal of Conflict Resolution 19: 532-557,

Bercovitch, J. (1984). Social conflict and third parties: Strategies of conflict resolution. Boul-

der, Colo.: "~'~stview Press.

. (1984a). "Problems and approaches in the study of bargaining and negotiation." Politi-

cal Science 36: 125-144.

Carnevale, P, J. (1986). "strategic choice in mediation." Negotiation Journal 2: 41-56.

• (1986a). "Mediating disputes and decisions in organizations, In Research on Negotiation

in Organizations (vol. 1), edited by R. Lewicki, B. Sheppard and M. Bazerman. Greenwich,

Conn.: JAI Press.

d e Reuck, A. ¥. S. (1983). 'A theory of conflict resolution by problem-solving:' In Man, Environ-

merit, Space and Time 3: 27-36.

D r t l c k m a ~ D, (1977). Negotiations: Social-psychologicalperspectives. London: Sage Publications.

French, J. R, and Raven, B. H. (1959). "The bases of social powers" In Studies in Social Power,

edited by D. Cartwright, Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Gulliver, P, H. (1979). Disputes and negotiations. New York: Academic Press.

Hill, B. J. (1982). 'Analysis of conflict resolution techniques." Journal of Conflict Resolution

26: 109-138.

K e i m a n , H. C. (t972). "The problem-solving workshop in conflict resolution" In Communica-

tion in internationalpolitics, edited by R.L. Merritt. Hobson, IU.: University of Illinois Press.

Kochan, T., and Jick, T. (1978), "The public sector mediation process: A theory and empirical

examination" Journal of Conflict Resolution 22: 209-238.

NegotiationJournal April 1992 111

Kolb, D. (1983). "Strategy and tactics of mediation." Human Relations 36: 247-268.

• (1983a). The mediators. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Kriesberg, L. (1991). "Fot~nal and quasi-mediators in international disputes: An exploratory anal-

ysis." Journal of Peace Research 28: 19-27.

Kressel, K. (1972). Labor mediation: An exploratory survey. New York: Association of Labor

Mediation Agencies.

Latour, S., et al. (1976), "Some determinants of preference for modes of conflict resolution."

Journal of Conflict Resolution 20: 319-356.

Rasler, K. A., and Thompson, W. R. (1989), War and state making. London: Unwin Hyman.

Raven, B. H. (1990). "Political applications and the psychology of interpersonal influence and

social power." Political Psychology I1: 493-520.

Rubin, J. Z. (1981). Dynamics of third party intervention: Kissinger in the Middle East. New

York: Praeger.

Saunders, H. (1991). "Officials and citizens in international relationships." In The Psychodynamics

of International Relationships, (~ol. 2), edited by V.D. Volkan, J.V. Montville, and D.A. Julius.

Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books.

Sheppard, 13. H. (1984). "Third party conflict intervention: A procedural framework:' In Research

in Organizational Behavior, (vol. 6), edited by B. Staw and L. Cummings. Greenwich, Conn.:

JAI Press.

Stein, J. G. (1985). "Structure, strategies and tactics of mediation: Kissinger and Carter in the

Middle East." Negotiation Journal 1: 331-347.

Stulberg, J. B. (1981). "The theory and practice of mediation: A reply to Professor Susskind"

Vermont Law Review 9: 85-117.

Susskind, L., and Cruickshank, J. (1987). Breaking the impasse. New York: Basic Books.

Tedeschi, J. T., Bonoma, T. V., and Schlenker, B. R. (1972). "Influence, decision and compli-

ance." In The Social Influence Process, edited by J.T. Tedeschi. Chicago: Aldine.

Thibaut, J. W., and Walker, L. (1975), Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. New York:

John Wiley.

Touval, S., and Zartman, I. W., eds, (1985). International mediation in theory and practice.

Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

Wall, J. A. (1981)• "Mediation: An analysis, review and proposed research." Journal of Conflict

Resolution 25: 157-180.

Waltz, K. (1959). Man, the state and war. New York: Columbia University Press.

Zartman, I. W., and Touval, S. (1985), "International mediation: Conflict resolution and power

politics." Journal of Social Issues 41: 27-46.

112 Jacob Bercovitch International Relations

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Labour CompiledDocument127 pagesLabour CompiledNithya GaneshNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Q. Strike and Its Provisions: UNIT-4Document19 pagesQ. Strike and Its Provisions: UNIT-4Nithya GaneshNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Critical Legal Studies:: Jurisprudence Important QuestionsDocument60 pagesCritical Legal Studies:: Jurisprudence Important QuestionsNithya GaneshNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Collective Bargaining (Obj, FeaturesDocument11 pagesCollective Bargaining (Obj, FeaturesNithya GaneshNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Conflict CR in Encyclopedia of GSDocument6 pagesConflict CR in Encyclopedia of GSNithya GaneshNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Constitution AssignmentDocument12 pagesConstitution AssignmentNithya GaneshNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Contoh RPHDocument2 pagesContoh RPHAhmad FawwazNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- PDF Kajaria Report Final - CompressDocument40 pagesPDF Kajaria Report Final - CompressMd Borhan Uddin 2035097660No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- 8th Chemical Effects of Electric Current Solved QuestionsDocument3 pages8th Chemical Effects of Electric Current Solved QuestionsGururaj KulkarniNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Class NotesDocument610 pagesClass NotesNiraj KumarNo ratings yet

- Ooip Volume MbeDocument19 pagesOoip Volume Mbefoxnew11No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Gravitation PDFDocument42 pagesGravitation PDFcaiogabrielNo ratings yet

- 33198Document8 pages33198tatacpsNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Weekly Progress Report PDFDocument7 pagesWeekly Progress Report PDFHeak Hor50% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- SAES-L-610 PDF Download - Nonmetallic Piping in Oily Water Services - PDFYARDocument6 pagesSAES-L-610 PDF Download - Nonmetallic Piping in Oily Water Services - PDFYARZahidRafiqueNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Installing TrollStore - iOS Guide PDFDocument2 pagesInstalling TrollStore - iOS Guide PDFThanh NgoNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Henning ResumeDocument1 pageHenning Resumeapi-341110928No ratings yet

- ITS US Special Edition 2017-18 - Volume 14 Issue 10Document15 pagesITS US Special Edition 2017-18 - Volume 14 Issue 10Leo Club of University of MoratuwaNo ratings yet

- Question Bank 1st UnitDocument2 pagesQuestion Bank 1st UnitAlapati RajasekharNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Why Facts Don't Change Our MindsDocument13 pagesWhy Facts Don't Change Our MindsNadia Sei LaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1-02 Data Collection and Analysis STATDocument12 pagesLesson 1-02 Data Collection and Analysis STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Stem D Chapter 1 3 Group 6sf RTPDocument35 pagesStem D Chapter 1 3 Group 6sf RTPKrydztom UyNo ratings yet

- Term SymbolDocument20 pagesTerm SymbolRirin Zarlina100% (1)

- Owner's Manual Pulsar NS160Document52 pagesOwner's Manual Pulsar NS160arNo ratings yet

- Iso 3675 en PDFDocument6 pagesIso 3675 en PDFGery Arturo Perez AltamarNo ratings yet

- Courses Offered in Spring 2015Document3 pagesCourses Offered in Spring 2015Mohammed Afzal AsifNo ratings yet

- Why Are You Applying For Financial AidDocument2 pagesWhy Are You Applying For Financial AidqwertyNo ratings yet

- All About Immanuel KantDocument20 pagesAll About Immanuel KantSean ChoNo ratings yet

- Implementation LabDocument7 pagesImplementation LabDavid BenjamingNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Final CDP MuzaffarpurDocument224 pagesFinal CDP MuzaffarpurVivek Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Aras Jung Curriculum IndividualDocument72 pagesAras Jung Curriculum IndividualdianavaleriaalvarezNo ratings yet

- SSP700ADocument4 pagesSSP700AKanwar Bir SinghNo ratings yet

- Mathchapter 2Document12 pagesMathchapter 2gcu974No ratings yet

- Deiparine, Jr. vs. Court of Appeals, 221 SCRA 503, G.R. No. 96643 April 23, 1993Document9 pagesDeiparine, Jr. vs. Court of Appeals, 221 SCRA 503, G.R. No. 96643 April 23, 1993CherNo ratings yet

- Hot-Rolled Steel Beam Calculation To AISC 360-16Document2 pagesHot-Rolled Steel Beam Calculation To AISC 360-16vanda_686788867No ratings yet

- 15 TribonDocument10 pages15 Tribonlequanghung98No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)