Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PIIS2215036618300968

Uploaded by

zuhrul_baladCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PIIS2215036618300968

Uploaded by

zuhrul_baladCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Antipsychotic drugs versus cognitive behavioural therapy

versus a combination of both in people with psychosis:

a randomised controlled pilot and feasibility study

Anthony P Morrison, Heather Law, Lucy Carter, Rachel Sellers, Richard Emsley, Melissa Pyle, Paul French, David Shiers, Alison R Yung,

Elizabeth K Murphy, Natasha Holden, Ann Steele, Samantha E Bowe, Jasper Palmier-Claus, Victoria Brooks, Rory Byrne, Linda Davies,

Peter M Haddad

Summary

Background Little evidence is available for head-to-head comparisons of psychosocial interventions and pharmacological Lancet Psychiatry 2018;

interventions in psychosis. We aimed to establish whether a randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural 5: 411–23

therapy (CBT) versus antipsychotic drugs versus a combination of both would be feasible in people with psychosis. Published Online

March 28, 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

Methods We did a single-site, single-blind pilot randomised controlled trial in people with psychosis who used S2215-0366(18)30096-8

services in National Health Service trusts across Greater Manchester, UK. Eligible participants were aged 16 years or See Comment page 381

older; met ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder, or met the entry criteria Division of Psychology and

for an early intervention for psychosis service; were in contact with mental health services, under the care of a Mental Health

consultant psychiatrist; scored at least 4 on delusions or hallucinations items, or at least 5 on suspiciousness, (Prof A P Morrison ClinPsyD,

persecution, or grandiosity items on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); had capacity to consent; H Law PhD, L Carter PhD,

R Sellers PhD, M Pyle PhD,

and were help-seeking. Participants were assigned (1:1:1) to antipsychotics, CBT, or antipsychotics plus CBT. Prof P French PhD,

Randomisation was done via a secure web-based randomisation system (Sealed Envelope), with randomised D Shiers MBChB,

permuted blocks of 4 and 6, stratified by gender and first episode status. CBT incorporated up to 26 sessions over Prof A R Yung PhD,

6 months plus up to four booster sessions. Choice and dose of antipsychotic were at the discretion of the treating J Palmier-Claus PhD, R Byrne PhD,

Prof P M Haddad MD), Division

consultant. Participants were followed up for 1 year. The primary outcome was feasibility (ie, data about recruitment, of Population Health, Health

retention, and acceptability), and the primary efficacy outcome was the PANSS total score (assessed at baseline, Services Research and Primary

6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks). Non-neurological side-effects were assessed systemically with the Antipsychotic Non- Care (Prof R Emsley PhD,

Prof L Davies PhD), and

neurological Side Effects Rating Scale. Primary analyses were done by intention to treat; safety analyses were done

Manchester Academic Health

on an as-treated basis. The study was prospectively registered with ISRCTN, number ISRCTN06022197. Science Centre Clinical Trials

Unit (Prof R Emsley), University

Findings Of 138 patients referred to the study, 75 were recruited and randomly assigned—26 to CBT, 24 to of Manchester, Manchester

Academic Health Science

antipsychotics, and 25 to antipsychotics plus CBT. Attrition was low, and retention high, with only four withdrawals

Centre, Manchester, UK; and

across all groups. 40 (78%) of 51 participants allocated to CBT attended six or more sessions. Of the 49 participants Greater Manchester Mental

randomised to antipsychotics, 11 (22%) were not prescribed a regular antipsychotic. Median duration of total Health NHS Foundation Trust,

antipsychotic treatment was 44·5 weeks (IQR 26–51). PANSS total score was significantly reduced in the combined Manchester, UK

(Prof A P Morrison, H Law,

intervention group compared with the CBT group (–5·65 [95% CI –10·37 to –0·93]; p=0·019). PANSS total scores did

L Carter, R Sellers, M Pyle,

not differ significantly between the combined group and the antipsychotics group (–4·52 [95% CI –9·30 to 0·26]; P French, D Shiers, Prof A R Yung,

p=0·064) or between the antipsychotics and CBT groups (–1·13 [95% CI –5·81 to 3·55]; p=0·637). Significantly fewer E K Murphy ClinPsyD,

side-effects, as measured with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale, were noted in the CBT N Holden DClinPsy, A Steele PhD,

S E Bowe DClinPsy,

group than in the antipsychotics (3·22 [95% CI 0·58 to 5·87]; p=0·017) or antipsychotics plus CBT (3·99 [95% CI

J Palmier-Claus, V Brooks RMN,

1·36 to 6·64]; p=0·003) groups. Only one serious adverse event was thought to be related to the trial (an overdose of R Byrne, Prof P M Haddad)

three paracetamol tablets in the CBT group). Correspondence to:

Dr Tony Morrison, Psychosis

Interpretation A head-to-head clinical trial of CBT versus antipsychotics versus the combination of the two is feasible Research Unit, Greater

Manchester Mental Health NHS

and safe in people with first-episode psychosis.

Foundation Trust, Manchester,

M25 3BL, UK

Funding National Institute for Health Research. tony.morrison@gmmh.nhs.uk

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction or other psychoses.1 Many clinical guidelines, therefore,

Schizophrenia and psychosis are associated with sub suggest that people with psychosis should be offered

stantial personal, social, and economic costs. High- both antipsychotics and CBT (as well as family

quality evidence from clinical trials shows that both interventions) and should be involved in collaborative

antipsychotics and cognitive behavioural (CBT) therapy decisions about treatment options.1 However, neither

can be helpful to adults with diagnoses of schizophrenia antipsychotics nor CBT are effective for everyone, and

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 411

Articles

Research in context

Evidence before this study randomly assigned to psychological treatment or

We searched PubMed with the terms “schizophrenia”, pharmacological treatment, or both, is possible. Our findings

“psychosis”, “psychological therapy”, “psychosocial suggest that antipsychotics, CBT, and the combination of the

intervention”, “CBT”, “antipsychotic” and “neuroleptic” for two are acceptable, safe, and helpful treatments for people

articles published in any language up to Jan 30, 2018. with early psychosis, but could have different cost–benefit

Although several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have profiles.

shown robust evidence that antipsychotics are superior to

Implications of all the available evidence

placebo and that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for

Our preliminary findings seem consistent with guidelines

psychosis in addition to antipsychotics is superior to

that recommend informed choices and shared decision

treatment as usual, we identified no randomised controlled

making about treatment options for early psychosis on the

trials in which a head-to-head comparison of CBT and

basis of cost–benefit profiles. An adequately powered efficacy

antipsychotics was done. A 2012 Cochrane review concluded

and effectiveness trial is now needed to test hypotheses

that no usable data were available to establish the relative

about superiority (eg, antipsychotics plus CBT vs

efficacy of antipsychotic medication and psychosocial

antipsychotics alone or CBT alone) and non-inferiority

interventions in early episode psychosis.

(eg, antipsychotics vs CBT).

Added value of this study

Our pilot and feasibility trial showed that a methodologically

rigorous clinical trial in which participants with psychosis are

the individual cost–benefit ratios of such treatments concern, in view of the increased cardiovascular mortality

(ie, the balance between efficacy and adverse effects) vary in people with psychosis compared with the general

substantially, both between and within individuals. population.10 Adverse effects of CBT in psychosis have

Meta-analyses2–4 of randomised controlled trials of CBT, not been well studied.2 Potential side-effects, such as

added to antipsychotics, for psychosis have shown effect stigma and deterioration of mental state,11 were not

sizes for both total symptoms and positive symptoms in detected in clinical trials of CBT for people with psychotic

the small-to-moderate range (generally 0·3–0·4 relative experiences. Rather, CBT resulted in significant

to treatment as usual, although the effect size is smaller reductions in the frequency of these side-effects.12,13

when lower quality trials are excluded). Meta-analyses5,6 However, CBT delivered in the context of a poor

of antipsychotics compared with placebo also show therapeutic relationship could be harmful.14

moderate benefits in terms of total and positive Whereas most evidence for the efficacy of CBT for

symptoms. The most comprehensive meta-analysis7 in psychosis is from randomised controlled trials in which

chronic schizophrenia showed a standardised effect size CBT was provided as an adjunct to antipsychotics

for total symptoms of 0·47 (95% CI 0·42–0·51). Although (ie, a combination of both vs antipsychotics alone),

CBT and antipsychotics are better than comparators preliminary evidence suggests that CBT might be helpful

(treatment as usual and placebo, respectively), the for people with psychosis who are not taking anti

proportion of individuals who achieve a clinically psychotics.13 No data for the relative head-to-head efficacy

meaningful benefit is moderate. For example, a meta- or acceptability of CBT and antipsychotics in schizo

analysis7 showed that 51% of multi-episode patients had phrenia are available. We investigated the feasibility of

at least a minimal response (≥20% reduction in doing a three-group randomised controlled trial of CBT,

symptoms as measured on the Positive and Negative antipsychotics, and a combination of CBT and anti

Syndrome Scale [PANSS] or Brief Psychiatric Rating psychotics in people with psychosis.

Scale), and 23% had a good response (≥50% reduction in

symptoms), to antipsychotics. By comparison, in first- Methods

episode psychosis, 81% of patients had at least a minimal Study design and participants

response, and 52% had a good response, to We did a single-blind, randomised, controlled pragmatic

antipsychotics.8 The authors of a meta-analysis2 claim pilot and feasibility trial between April 1, 2014, and

that conclusions about the efficacy of CBT have been June 30, 2017 in four specialist mental health National

exaggerated, given that most large, robust trials have not Health Service trusts in Greater Manchester, UK.

shown significant effects at end of treatment, and that Eligible participants were aged 16 years or older; met

effect sizes are reduced overall if only studies of high ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective

quality are included in meta-analyses. disorder, or delusional disorder, or met the entry criteria

Antipsychotics are associated with a wide range of for an early intervention for psychosis service

adverse effects.5,9 Metabolic effects are of particular (operationally defined with the PANSS), because most

412 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018

Articles

individuals with first-episode psychosis will receive care Treatment was begun as soon as possible after

from specialist teams, as recommended by National randomisation. Prescribing mirrored standard clinical

Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines; practice, and thus there were no restrictions on the

were in contact with mental health services, under the antipsychotics that could be selected or their doses.

care of a consultant psychiatrist; scored at least 4 on the Clinicians could switch antipsychotics and adjust doses

PANSS delusions or hallucinations items, or at as clinically indicated, but were encouraged to continue

least 5 on suspiciousness, persecution, or grandiosity antipsychotic treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks,

items; and had to have the capacity to consent and also and preferably for at least 26 weeks. Participants

had to be help-seeking. allocated to the combined treatment group were offered

Exclusion criteria were receipt of antipsychotic CBT and antipsychotic medications as described for the

medication or structured CBT with a qualified therapist monotherapy groups.

within the past 3 months, moderate-to-severe learning Clinicians could prescribe drugs other than anti

disabilities, organic impairment, a score of 5 or more on psychotics, including antidepressants, anxiolytics, and

the PANSS conceptual disorganisation item, and a hypnotics, for all participants. Participants were offered

primary diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependence; monitoring assessments at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks,

patients who were an immediate risk to themselves or and 52 weeks. At each assessment, we measured

others, and those who did not speak English were also weight, blood pressure, HbA1c concentrations, fasting

excluded. The PANSS was administered by a research glucose concentrations, and fasting lipids (ie, total

assistant in the participant’s home or a suitable clinical cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides and prolactin

service to establish eligibility, which was confirmed by a concentrations). To allay concerns about the safety of

qualified clinician. Our trial protocol was approved by the withholding antipsychotics medication in the CBT

National Research Ethics Service of the UK’s National group, trial procedures included monitoring for

Health Service (14/NW/0041). All participants provided

written informed consent.

138 people screened for eligibility

Randomisation and masking

Participants were recruited via care coordinators, 63 not eligible

consultant psychiatrists, and other mental health staff 36 did not meet inclusion criteria

22 declined to participate

within participating mental health National Health 5 had other reasons

Service trusts. Eligible participants were then randomly

assigned (1:1:1) to antipsychotics, CBT, or antipsychotics

plus CBT via a secure web-based randomisation system 75 randomly assigned

(Sealed Envelope) operated by the trial administrator.

We used randomised permuted blocks of 4 and 6,

stratified by gender and first episode status. 26 allocated to cognitive 24 allocated to antipsychotics 25 allocated to cognitive

Randomisation at the individual level was independent behavioural therapy behavioural therapy and

and concealed, with all assessors masked to group antipsychotics

allocation. Allocation was subsequently made known to

the trial manager, trial administrator, and therapists. 20 completed 6-week assessment 22 completed 6-week assessment 20 completed 6-week assessment

Participants and their care team were informed of the 6 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 4 missed the assessment

allocation by letter. 1 withdrew 1 withdrew

Procedures 23 completed 12-week 22 completed 12-week 20 completed 12-week

Participants allocated to CBT were offered up to assessment assessment assessment

3 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 4 missed the assessment

26 sessions of therapy based on a specific cognitive 1 withdrew 1 withdrew

model15 during a 6-month treatment window. Up to

four optional booster sessions were available during

the subsequent 6 months. Therapy was individualised 22 completed 24-week 22 completed 24-week 20 completed 24-week

assessment assessment assessment

and problem focused. Permissible interventions were 3 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment

described in the manualised treatment protocol.16 1 withdrew 1 withdrew 2 withdrew

Therapy sessions were usually offered weekly and

delivered by appropriately qualified psychological

21 completed 52-week 22 completed 52-week 20 completed 52-week

therapists. Fidelity to protocol was ensured by weekly assessment assessment assessment

supervision and regular rating of recorded sessions 4 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 3 missed the assessment

with the Cognitive Therapy Scale–Revised.17 1 withdrew 1 withdrew 2 withdrew

Participants allocated to antipsychotics were pre

scribed medication by their responsible psychiatrist. Figure: Trial profile

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 413

Articles

remained in the trial, and the assessment schedule was

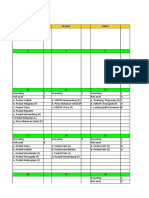

Antipsychotics (n=24) CBT (n=26) Antipsychotics plus

CBT (n=25) maintained. Participants were also given the option to

move into the combined treatment group if deterioration

Age, years 23·21 (4·97) 23·19 (6·32) 24·44 (6·86)

in mental state led to involuntary hospitalisation, or if

Sex

there was a greater than 25% deterioration in PANSS

Male 13 (54%) 16 (62%) 14 (56%)

scores at the 6-week assessment or a greater than

Female 11 (46%) 10 (38%) 11 (44%)

12·5% deterioration in PANSS scores at the 12-week

First-episode psychosis: 24:0 24:2 25:0

multiple episode

assessment.

psychosis

Duration of untreated 37·33 (44·41) 44·48 (52·30) 39·43 (35·76) Outcomes

psychosis, weeks The primary outcome was feasibility, which was

PANSS operationalised in terms of referral rates, recruitment,

Total 70·17 (10·12) 70·50 (8·12) 70·76 (8·45) retention or attrition, acceptability of treatment,

Positive 23·04 (4·60) 23·15 (4·63) 21·92 (3·63) attendance at sessions, adherence to homework, and

Negative 16·17 (5·72) 15·50 (4·10) 15·24 (5·17) compliance with medication. The primary effectiveness

Disorganised 16·25 (2·60) 17·15 (3·65) 17·8 (4·27) outcome was total score on PANSS18—a 30-item,

Excitement 18·25 (4·35) 17·85 (3·86) 17·4 (4·14) semi-structured interview assessing dimensions of

Emotional Distress 25·46 (5·00) 25·31 (3·83) 26·28 (3·47) psychosis symptoms rated on a seven-point scale

Questionnaire about 38·71 (9·23) 40·13 (9·33)* 41·8 (11·79) between 1 (absent) and 7 (severe)—which was assessed

Process of Recovery at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 52 weeks.

HADS† Secondary clinical outcomes were depression and

Total 41·05 (5·49) 37·54 (5·42) 36·36 (6·76) anxiety (assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and

Anxiety 21·96 (2·62) 20·50 (3·32) 19·36 (3·89) Depression Scale19), quality of life (assessed with

Depression 19·05 (4·87) 17·38 (3·32) 17·28 (5·55) the WHO Quality of Life20), social functioning

WHO quality of life score‡ 67·03 (14·99) 68·66 (13·41) 70·18 (15·41) (assessed with the Personal and Social Performance

Personal and Social 52·67 (13·83) 57·38 (12·04) 58·16 (11·1) scale21), user-defined recovery (measured with the

Performance Scale Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery22), and

CGI results on the Clinical Global Impressions of symptom

Participant version 4·91 (0·97)§ 4·42 (0·99) 4·38 (1·54) severity and improvement scale.23 Instruments were

Clinician version 4·13 (0·74) 4·08 (0·63) 4·04 (0·68) administered by research assistants trained in their use

ANNSERS to achieve a good level of inter-rater reliability (intraclass

Number of side-effects 9·96 (4·72), 24 8·88 (3·77), 26 9·16 (4·69), 25 correlation coefficient 0·902).

Total 13·92 (7·05), 24 12·12 (6·55), 26 12·28 (6·61), 25 Service use, diagnosis, and antipsychotic prescribing

Cholesterol were recorded via review of case notes. Duration of

Total (mmol/L) 4·54 (0·91), 20 4·08 (0·82), 15 4·45 (0·93), 16 antipsychotic treatment for each participant was

HDL (mmol/L) 1·34 (0·35), 20 1·13 (0·30), 15 1·38 (0·40), 15 based on all regular antipsychotics prescribed and

Total/HDL 3·57 (0·94), 20 3·5 (0·86), 15 3·35 (0·93), 15 was not restricted to the primary antipsychotic

LDL (mmol/L) 2·58 (0·78), 15 2·33 (0·67), 12 2·46 (0·68), 14 (ie, the antipsychotics prescribed for the longest during

Triglycerides (mmol/L) 1·15 (0·39), 16 1·27 (0·64), 12 1·12 (0·45), 14 the study). Non-neurological side-effects were assessed

Prolactin (mU/L) 183·06 (89·71), 17 187·07 (63·33), 15 198·5 (81·78), 14 systemically with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological

Glucose (mmol/L) 6·27 (6·96), 18 5·32 (2·41), 15 4·14 (0·55), 15 Side Effects Rating Scale.24 At 6 months, we obtained

self-report data for antipsychotic adherence in the past

Data are mean (SD); mean (SD), number of observations; or n (%), unless otherwise specified. CBT=cognitive month on a visual analogue scale. At the 52-week visit,

behavioural therapy. PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

CGI=Clinical Global Impressions of Symptom Severity and Improvement Scale. ANNSERS= Antipsychotic we surveyed participants’ opinions on their preferences

Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale. *n=25. †n=23 in the antipyschotics group and 24 in the CBT group. and views of measures used in the study to inform

‡n=25 in the CBT group and 24 in the antipsychotics plus CBT group. §n=22. choice of measures for a definitive trial.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics After the original ethical approval for the trial in

February, 2014, a substantial protocol amendment was

made (and approved on July 7, 2014): the lower age limit

deterioration. Any participant randomly assigned to was changed from 18 years to 16 years, being an

either CBT alone or antipsychotics alone could be inpatient was removed as an exclusion criterion, posing

moved to the combined treatment group if their mental an immediate risk to self or others was introduced as

state declined during the trial (this procedure was an exclusion criterion, and the randomisation

detailed in the standard operating procedures for the timeframe was amended from 2 working days to

study and was presented to the Research Ethics 5 working days. Other minor amendments included the

Committee and clinicians who referred to the study). addition of service user and clinician surveys to gather

Participants who experienced such deterioration information about the feasibility of recruitment. We had

414 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018

Articles

originally proposed that the recruitment window would

Randomly assigned treatment group Total

be variable, with participants recruited in the first

22 months receiving a full 6 months’ follow up and Antipsychotics CBT Antipsychotics

(n=24) (n=26) plus CBT (n=25)

participants recruited thereafter offered assessments up

to the end of treatment. However, we agreed a no-cost Treatment received

extension with the funder, and were thus able to Antipsychotics 15 2 4 21

complete 12-month follow-up visits for all participants. CBT 0 15 5 20

We also originally proposed that economic analyses Antipsychotics 1 6 14 21

plus CBT

would explore the costs of health and social care and

Neither 8 3 2 13

quality-adjusted life years from a broadly societal

perspective. However, the EQ5D was erroneously CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy.

omitted from our assessment battery, meaning that such

Table 2: Participants’ randomly assigned treatment vs treatment received

analyses were not possible.

Statistical analysis referral to recruitment rate was roughly 2:1, with only

The sample size was based on recommendations for 22 (16%) of 138 referred patients declining to participate.

obtaining reliable sample size estimates in pilot and 73 patients were experiencing first-episode psychosis

feasibility studies,25 which suggested that 75 patients and recruited from early-intervention services; the other

would be needed (ie, 25 in each group), with the aim of two patients had multiple previous episodes and were

achieving usable data for 60 participants across the recruited from community mental health services. Most

three groups, allowing for a dropout rate of 20%.26 participants did not have diagnoses in their medical

Primary analysis was by intention to treat. We fitted records at baseline. The most common entry was first-

random intercept models with summed scores as episode psychosis, and the most common formal ICD-

dependent variables, allowing for attrition and the 10 diagnosis was F29 unspecified non-organic psychosis.

variable follow-up times introduced by trial design. Participants from ten of the 22 participating clinical

Covariates were sex, age, time, and the baseline value of teams (appendix) were randomly assigned. Retention

the relevant outcome measure (first episode status, as a was reasonable, with only four withdrawals and low

stratification factor, should have been included, but attrition, which were balanced across the groups

because only two participants were not having their first (figure). Nine (12%) partial blind breaks (ie, only one

episode of psychosis, age was a more appropriate treatment was revealed) and five (7%) full blind breaks

covariate). The use of these models allowed for analysis (ie, actual randomly assigned group was revealed) were

of all available data, on the assumption that data were reported by research assistants. Four of the full blind

missing at random,27 conditional upon covariates. All breaks were in the antipsychotic arm, and one was in

treatment effects reported are estimates of the effects the combined arm. Only 3 (1%) of 256 follow-up

common to all follow-up times (essentially, repeated assessments were done by an unmasked assessor (the

measures ANCOVAs). Because safety and unwanted blind was broken during the assessment). All three of

effects should be analysed on the basis of the most these assessments were then scored by a masked rater,

accurate information, these results are reported with an and consensus was reached on ratings. Thus, no

as-treated rather than an intention-to-treat approach. As- assessments were done without rater masking

treated was defined with our predefined minimum Participants who were assigned to CBT (either mono

dose criteria for antipsychotics (ie, at least 6 weeks at therapy or in the combined group) received a mean of

a therapeutic dose) and CBT (at least six sessions). 14·39 sessions (SD 9·12; range 0–26) within 6 months,

We used Stata (version 14.2) for all analyses. This with each session lasting around an hour (additional

trial was prospectively registered with ISRCTN booster sessions were also offered as appropriate).

(number ISRCTN06022197). 40 (78%) of 51 participants attended six or more sessions,

and only one participant (2%) attended no sessions.

Role of the funding source Homework compliance was good for both participants

The funder had no role in study design; data collection, and therapists: 404 (73%) of 557 participant between-

analysis, or interpretation; or writing of the Article. The session tasks and 396 (89%) of 445 therapist between-

corresponding author and RE had access to all study session tasks were completed.

data, and the corresponding author had final Of the 49 participants assigned to antipsychotics

responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. (either alone or in combination with CBT), 11 (22%) were

not prescribed a regular antipsychotic for various

Results reasons, including five participants who declined to

Between May 1, 2014 and Aug 30, 2016, we recruited take an antipsychotic despite consenting to enter the

75 participants, 26 to CBT, 24 to antipsychotics, and trial. The primary antipsychotics prescribed most

25 to antipsychotics plus CBT (figure; table 1). The frequently were aripiprazole (n=14), olanzapine (n=10),

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 415

Articles

Antipsychotics CBT (n=26) Antipsychotics plus Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

(n=24) CBT (n=25)

CBT vs antipsychotics CBT vs antipsychotics Antipsychotics vs

plus CBT antipsychotics plus CBT

Total ·· ·· ·· –1·13 (2·39; –5·81 to –5·65 (2·41; –10·37 to –4·52 (2·44; –9·30 to

3·55); 0·637 –0·93); 0·019 0·26); 0·064

Week 0 70·13 (10·11), 24 70·35 (8·03), 26 70·76 (8·46), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 64·05 (11·39), 22 64·85 (7·85), 20 64·70 (9·74), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 60·81 (16·52), 21 63·74 (7·73), 23 58·40 (14·51), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 61·09 (14·44), 22 60·50 (8·74), 22 53·77 (12·54), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 56·77 (14·10), 22 58·14 (11·68), 21 57·40 (13·58), 20 ·· ·· ··

Positive ·· ·· ·· –1·16 (1·14; –3·40 to –2·02 (1·15; –4·27 to –0·86 (1·17; –3·15 to

1·09); 0·312 0·24); 0·080 1·43); 0·462

Week 0 23·04 (4·60), 24 23·15 (4·63), 26 21·92 (3·63), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 19·36 (5·44), 22 21·00 (4·38), 20 20·10 (4·41), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 19·19 (7·72), 21 21·00 (4·72), 23 17·40 (5·65), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 17·81 (6·85), 21 18·18 (4·81), 22 15·23 (5·31), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 18·18 (6·52), 22 17·90 (5·92), 21 16·80 (6·05), 20 ·· ·· ··

Negative ·· ·· ·· –1·25 (0·78; –2·78 to –2·31 (0·79; –3·85 to –1·06 (0·79; –2·61,

0·28); 0·110 –0·77); 0·003 0·49); 0·178

Week 0 16·17 (5·72), 24 15·50 (4·10), 26 15·24 (5·17), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 14·64 (5·06), 22 15·05 (3·52), 20 13·90 (4·85), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 14·00 (4·32), 21 14·83 (3·10), 23 13·00 (5·23), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 14·14 (5·47), 22 14·91 (4·72), 22 12·41 (4·60), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 12·73 (4·58), 22 14·62 (4·52), 21 12·80 (3·68), 20 ·· ·· ··

Disorganised ·· ·· ·· –0·19 (0·77; –1·69 to –0·85 (0·77; –2·36 to –0·66 (0·80; –2·22 to

1·32); 0·809 0·66); 0·273 0·90); 0·408

Week 0 16·25 (2·59), 24 17·15 (3·65), 26 17·80 (4·27), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 15·77 (3·18), 22 16·8 (2·91), 20 17·50 (4·01), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 15·19 (4·96), 21 16·39 (3·37), 23 16·25 (4·10), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 15·10 (3·86), 21 15·50 (3·53), 22 14·50 (3·78), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 14·82 (3·67), 22 15·67 (3·73), 21 15·80 (4·25), 20 ·· ·· ··

Excitement ·· ·· ·· –0·45 (0·75; –1·91 to –0·80 (0·75; –2·27 to –0·35 (0·76; –1·84 to

1·02); 0·549 0·67); 0·286 1·13); 0·641

Week 0 18·25 (4·35), 24 17·85 (3·86), 26 17·4 (4·14), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 15·95 (4·09), 22 15·90 (3·93), 20 15·75 (4·05), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 15·52 (4·77), 21 15·52 (3·16), 23 14·35 (4·97), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 14·77 (3·37), 22 14·45 (3·40), 22 12·86 (4·36), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 13·41 (4·07), 22 13·62 (2·89), 21 13·80 (4·26), 20 ·· ·· ··

Emotional ·· ·· ·· 0·0 (1·11; –2·17 to –1·93 (1·12; –4·12 to –1·93 (1·13; –4·15 to

distress 2·18); 0·999 0·26); 0·084 0·29); 0·088

Week 0 25·46 (5·00), 24 25·31 (3·83), 26 26·28 (3·47), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 22·55 (5·21), 22 21·50 (4·27), 20 23·10 (3·93), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 21·38 (6·91), 21 22·48 (4·31), 23 19·60 (5·74), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 21·55 (5·75), 22 20·95 (3·70), 22 17·50 (5·49), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 19·86 (6·12), 22 19·10 (5·49), 21 20·10 (5·08), 20 ·· ·· ··

Data are mean (SD), number of observations, unless otherwise specified. The effects are common to all follow-up times and are analysed by intention to treat. CBT=cognitive

behavioural therapy.

Table 3: Outcomes on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

and quetiapine (n=10), as chosen by the treating antipsychotic for 6 weeks or more (duration was not

psychiatrist in the participants’ clinical care team captured for one participant). The median duration of

(appendix). 12 (32%) of the 38 participants treated with total antipsychotic treatment was 44·5 weeks (IQR 26–51;

antipsychotics switched antipsychotics at least once. range 2–52). 28 (78%) of 36 participants with accurate

34 (92%) of 37 participants who commenced anti- duration data were taking antipsychotic medication at

psychotic treatment were prescribed their primary the end of the study.

416 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018

Articles

Antipsychotics (n=24) CBT (n=26) Combination (n=25) Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

CBT vs CBT vs antipsychotics Antipsychotics vs

antipsychotics plus CBT antipsychotics plus CBT

QPR ·· ·· ·· –0·93 (2·97; –6·76 4·01 (3·14; –2·15 4·94 (3·05; –1·03 to

to 4·90); 0·754 to 10·17); 0·202 10·91); 0·105

Week 0 38·71 (9·23), 24 40·13 (9·33), 25 41·8 (11·79), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 44·86 (14·99), 22 47·81 (8·86), 21 52 (14·05), 18 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 48·55 (14·73), 22 51·62 (9·25), 21 49·88 (11·04), 17 ·· ·· ··

HADS

Total ·· ·· ·· –0·60 (1·98; –4·48 –2·93 (2·03; –6·90 –2·32 (1·99; –6·22

to 3·27); 0·761 to 1·04); 0·148 to 1·56); 0·241

Week 0 41·05 (5·49), 23 37·54 (5·42), 24 36·36 (6·76), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 35·55 (7·69), 22 35·36 (12·61), 22 30·37 (9·28), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 34·27 (9·08), 22 32·14 (6·96), 21 30·35 (6·98), 17 ·· ·· ··

Anxiety ·· ·· ·· 0·62 (1·28; –1·89 –1·34 (1·32; –3·92 to –1·96 (1·30; –4·50

to 3·14); 0·627 1·25); 0·310 to 0·58); 0·131

Week 0 21·96 (2·62), 23 20·5 (3·32), 24 19·36 (3·89), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 19·36 (4·51), 22 19·18 (10·80), 22 15·65 (5·98), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 18·73 (5·03), 22 17·29 (4·64), 21 15·67 (4·89), 18 ·· ·· ··

Depression ·· ·· ·· –0·14 (1·20; –2·49 –1·60 (1·27; –4·08 to –1·46 (1·20; to –3·82

to 2·20); 0·905 0·88); 0·206 to 0·90); 0·226

Week 0 19·05 (4·87), 23 17·38 (3·32), 24 17·28 (5·55), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 16·27 (5·84), 22 15·18 (3·81), 22 13·42 (5·83), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 14·91 (5·52), 22 14·05 (4·2), 21 14·94 (5·36), 17 ·· ·· ··

WHO quality of ·· ·· ·· 0·62 (3·20; –5·65 5·82 (3·37; –0·78 5·21 (3·39; –1·43

life score to 6·88); 0·847 to 12·42); 0·084 to 11·84); 0·124

Week 0 67·03 (14·99), 24 68·66 (13·41), 25 70·18 (15·41), 24 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 72·5 (19·84), 22 76·78 (14·79), 18 77·82 (14·06), 17 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 77·29 (21·31), 21 79·29 (16·59), 21 85·83 (17·59), 18 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 79·15 (20·95), 20 79·10 (14·03), 21 89·06 (18·87), 18 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 81·36 (20·02), 22 83·81 (15·23), 21 82·93 (19·17), 15 ·· ·· ··

PSP ·· ·· ·· 3·18 (4·18; –5·02 2·17 (4·27; –6·19 –1·01 (4·24; –9·32 to

to 11·38); 0·448 to 10·53); 0·611 7·30); 0·812

Week 0 52·67 (13·83), 24 57·38 (12·04), 26 58·16 (11·1), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 63·95 (18·53), 22 60·05 (10·51), 22 62·48 (17·47), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 60·45 (17·61), 22 60·95 (12·93), 21 61 (16·47), 20 ·· ·· ··

CGI

Clinician ·· ·· ·· –0·16 (0·28; –0·70 –0·64 (0·29; 1·20 –0·48 (0·28; –1·03 to

to 0·38); 0·569 to –0·08); 0·026 0·07); 0·087

Week 0 4·13 (0·74), 24 4·08 (0·63), 26 4·04 (0·68), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 3·32 (1·17), 22 3·45 (0·91), 22 2·86 (1·06), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 3·23 (1·11), 22 3·38 (1·07), 21 3·00 (1·08), 20 ·· ·· ··

Patients ·· ·· ·· 0·35 (0·41; –0·44 –0·29 (0·42; 1·11 –0·65 (0·42; –1·46

to 1·15); 0·385 to 0·52); 0·482 to 0·17); 0·119

Week 0 4·91 (0·97), 22 4·42 (0·99), 26 4·38 (1·54), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 4·33 (1·56), 21 3·71 (1·23), 21 3·20 (1·54), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 3·91 (1·48), 22 3·50 (1·50), 20 3·94 (1·59), 18 ·· ·· ··

Clinician – ·· ·· ·· 0·05 (0·31; –0·56 –0·53 (0·32; –1·16 to –0·58 (0·31; –1·19 to

improvement to 0·65); 0·876 0·10); 0·097 0·03); 0·064

Week 0 ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ··

Week 24 2·95 (1·21), 22 2·78 (1·23), 22 2·14 (0·91), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 2·45 (1·06), 22 2·50 (1·00), 20 2·25 (1·12), 20 ·· ·· ··

Data are mean (SD), number of observations, unless otherwise specified. The effects are common to all follow-up times and are analysed by intention to treat. CBT=cognitive

behavioural therapy. QPR=Questionnaire about Process of Recovery. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PSP=Personal and Social Performance Scale. CGI=Clinical Global

Impressions of Symptom Severity and Improvement Scale.

Table 4: Secondary outcomes

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 417

Articles

very similar across all groups at 12 months (table 5). In

Deterioration Improvement

the as-treated analysis, few deteriorations were noted

>25% >50% >25% >50% in any groups at both 6 months and 12 months (table 5).

Intention-to-treat analysis Adverse effects (as measured by ANNSERS) were

24 weeks significantly less common in the CBT group than in

CBT 0 2 8 2 the antipsychotics (p=0·017) or the antipsychotics plus

Antipsychotics 0 1 5 3 CBT (p=0·003) groups (table 6). The difference in

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 0 11 7 adverse effects between the combined group and the

52 weeks antipsychotics group was not significant (table 6). In the

CBT 0 1 8 4 as-treated analysis, no hospital admissions were recorded

Antipsychotics 2 0 8 5 among those in the antipsychotics group or those who

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 0 7 6 received no interventions (appendix). Two participants in

As-treated analysis the CBT group (four admissions) and four people in the

24 weeks combined group were admitted to hospital (appendix).

CBT 0 1 8 3 Only three deteriorations were noted at 6 or 12 weeks in

Antipsychotics 0 1 3 2 monotherapy participants (two in the antipsychotics

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 1 9 4 group and one in the CBT group).

Neither 0 0 4 3

We recorded another ten potential serious adverse

52 weeks

events in nine participants (appendix). Only one of these

CBT 0 0 6 6

events was thought to be related to the trial (the overdose

of three paracetamol tablets in a participant in the CBT

Antipsychotics 2 0 6 0

group). Only three participants (two in the antipsychotics

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 1 8 4

group, one in the CBT group) met our deterioration

Neither 0 0 3 5

criteria at 6 or 12 weeks, which prompted an offer to

Data are n. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. move into the combined arm.

Table 5: Participants with improvements or deteriorations in total

scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale at 24 and 52 weeks Discussion

Our single-blind, randomised, controlled pragmatic

pilot and feasibility trial showed that a study comparing

Self-reported data for medication adherence were antipsychotics, CBT, and antipsychotics plus CBT is

available at 6 months for 42 (86%) of the 49 participants possible in people with psychosis. Our trial had low

(86%) assigned to antipsychotics. 29 participants (69%) attrition (<20% at each timepoint) that was balanced

reported that they were taking an antipsychotic at that across interventions, and only a small proportion of

timepoint, among whom mean adherence was participants received an intervention to which they were

77% (SD 29·19, range 0–100; on a scale on which not allocated. All three interventions were broadly safe

100% indicates they had taken every dose over the past and acceptable.

month). The mean baseline PANSS total score in the overall

The proportion of patients receiving allocated population was 70·4, which is similar to the baseline

interventions was similar across groups (table 2). PANSS score of 73·8 seen in the CAFÉ study,29 but lower

15 patients (58%) in the CBT group, 15 (63%) in the than the baseline score of 88·5 in EUFEST30 (CAFÉ and

antipsychotics group, and 14 (56%) in the combined EUFEST are large, 1-year randomised controlled trials of

group received the correct allocated intervention. antipsychotics in early psychosis). The mean changes in

Psychiatric symptoms were significantly reduced over PANSS total scores we noted from baseline to 52 weeks

time across all conditions (appendix). The PANSS total (antipsychotics 13·3, CBT 12·3, antipsychotics plus

score differed significantly between the combined group CBT 13·4) were all within the range of those noted with

and the CBT group (p=0·019), but not between the three antipsychotics in CAFÉ (olanzapine 18·4,

the combined group and the antipsychotics group quetiapine 15·6, risperidone 8·4), but lower than those

(p=0·064), or between the CBT group and the in EUFEST (changes of around 35 points with the five

antipsychotics group (p=0·637; table 3). Table 4 shows antipsychotics assessed). The mean PANSS reductions

results for secondary outcomes. PANSS analyses that we noted were less than the 15 points estimated to be

did not include age as a covariate had similar results to equivalent to a rating of minimal improvement on the

the primary analyses (appendix). Clinical Global Impressions scale,31 although the

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the numbers threshold for minimal improvement could be lower for

of participants in each group (completer-only patients with less severe symptoms at baseline.31 The

data—ie, observed cases) achieving 25% and reductions in our trial were larger than the minimal

50% improvements on adjusted PANSS total scores28 clinically important difference in PANSS total score

were highest in the combined arm at 6 months, and estimated to be associated with obtaining employment

418 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018

Articles

Antipsychotics CBT (n=20) Antipsychotics plus Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

(n=21) CBT (n=21)

CBT vs antipsychotics CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT Antipsychotics vs

antipsychotics plus CBT

ANNSERS

Number of side-effects ·· ·· ·· 3·22 (1·35; 0·58 to 5·87); 3·99 (1·35; 1·36 to 6·64); 0·78 (1·37; –1·91 to 3·47);

0·017 0·003 0·572

Week 0 8·52 (3·66), 21 8·55 (3·94), 20 10·33 (4·54), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 8·47 (5·62), 17 5·7 (3·23), 20 10·05 (5·35), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 9·06 (5·5), 16 4·74 (3·35), 19 10·42 (5·90), 19 ·· ·· ··

Total score ·· ·· ·· 5·12 (2·05; 1·11 to 9·14); 6·30 (2·03; 2·32 to 10·27); 1·17 (2·07; –2·89 to 5·24);

0·012 0·002 0·571

Week 0 11·57 (5·48), 21 11·7 (6·21), 20 13·62 (6·18), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 11·59 (8·40), 17 7·45 (4·99), 20 14·16 (8·42), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 12·94 (8·77), 16 6·21 (5·07), 19 13·79 (7·63), 19 ·· ·· ··

Cholesterol

HDL (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· 0·07 (0·09; –0·10 to 0·24); 0·09 (0·09; –0·09 to 0·26); 0·01 (0·08; –0·15 to 0·17);

0·389 0·346 0·893

Week 0 1·37 (0·35), 16 1·21 (0·32), 12 1·37 (0·41), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 1·37 (0·38), 14 1·21 (0·29), 9 1·54 (0·49), 15 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 1·15 (0·36), 8 1·36 (0·31), 6 1·24 (0·21), 7 ·· ·· ··

Total/HDL ratio ·· ·· ·· –0·08 (0·22; –0·50 to 0·35); 0·01 (0·24; –0·45 to 0·48); 0·09 (0·21; –0·33 to 0·51);

0·722 0·950 0·667

Week 0 3·4 (0·85), 16 3·58 (0·66), 12 3·06 (0·81), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 3·63 (1·25), 14 3·64 (0·44), 10 3·23 (0·65), 14 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 4·41 (2·11), 8 3·51 (0·53), 7 3·68 (1·05), 6 ·· ·· ··

LDL (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· –0·21 (0·28; –0·76 to 0·33); –0·15 (0·29; –0·72 to 0·42); 0·06 (0·26; –0·45 to 0·58);

0·449 0·615 0·809

Week 0 2·42 (0·79), 14 2·44 (0·58), 10 2·34 (0·72), 11 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 2·59 (0·72), 12 2·79 (0·92), 8 2·63 (0·74), 12 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 3·02 (0·84), 6 2·83 (0·59), 6 2·63 (0·90), 6 ·· ·· ··

Triglycerides (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· 0·08 (0·19; –0·29 to 0·45); –0·27 (0·20; –0·66 to 0·12); –0·35 (0·18; –0·71 to 0·00);

0·659 0·170 0·051

Week 0 1·23 (0·45), 14 1·16 (0·56), 10 1·15 (0·58), 11 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 1·45 (0·75), 12 1·4 (0·63), 8 1·11 (0·63), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 1·62 (1·11), 6 0·97 (0·28), 6 2·57 (4·08), 7 ·· ·· ··

Prolactin (mU/L) ·· ·· ·· 23·12 (26·73; –29·27 to –7·39 (29·00; –64·22 to –30·51 (28·28; –85·94 to

75·50); 0·387 49·44); 0·799 24·93); 0·281

Week 0 162·86 (98·96), 14 188·42 (72·73), 12 221·58 (74·14), 12 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 206·92 (83·76), 13 196·22 (83·08), 9 180 (73·90), 10 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 136·71 (53·84), 7 201·83 (93·32), 6 186·13 (88·69), 8 ·· ·· ··

Glucose (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· –0·56 (0·50; –1·53 to 0·42); –0·75 (0·52; –1·77 to 0·27); –0·19 (0·45; –1·07 to 0·68);

0·265 0·148 0·662

Week 0 6·6 (7·63), 15 5·04 (2·68), 12 4·72 (0·95), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 4·76 (1·10), 11 5·2 (1·72), 7 4·55 (0·55), 14 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 4·63 (0·65), 8 5·32 (1·81), 6 4·11 (0·76), 7 ·· ·· ··

Weight (kg) ·· ·· ·· 1·80 (1·40; –0·94 to 4·54); 3·70 (1·41; 0·93 to 6·47); 1·90 (1·36; –0·76 to 4·57);

0·198 0·009 0·162

0 75·91 (20·31), 21 73·62 (15·72), 18 70·93 (12·97), 21 ·· ·· ··

6 77·06 (18·20), 16 74·84 (17·27), 15 70·82 (13·56), 18 ·· ·· ··

12 72·87 (13·32), 16 73·58 (15·66), 19 73·86 (14·01), 19 ·· ·· ··

24 78·21 (17·38), 18 72·12 (15·14), 20 75·33 (13·59), 16 ·· ·· ··

52 74·87 (15·34), 16 75·71 (14·88), 15 75·22 (15·07), 18 ·· ·· ··

(Table 6 continues on next page)

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 419

Articles

Antipsychotics CBT (n=20) Antipsychotics plus Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

(n=21) CBT (n=21)

CBT vs antipsychotics CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT Antipsychotics vs

antipsychotics plus CBT

(Continued from previous page)

Systolic blood pressure ·· ·· ·· 1·36 (2·76; –4·06 to 6·78); 0·52 (2·83; –5·04 to 6·07); –0·84 (2·44; –5·61 to 3·93);

(mm Hg) 0·624 0·855 0·730

Week 0 124·12 (12·91), 20 124·05 (15·02), 14 118·98 (11·11), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 124·49 (16·53), 14 122·13 (10·16), 14 123·86 (14·13), 17 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 123·6 (13·28), 16 122·22 (10·67), 10 116·9 (8·47), 18 ·· ·· ··

Data are mean (SD), number of observations on an as-treated basis, unless otherwise specified. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. ANNSERS=Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale.

*ANNSERS consists of 43 non-neurological side-effects, each rated as absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3), with a total possible score of 129.

Table 6: Secondary outcomes (adverse effects)

as an objective measure of functioning (8·3 points),32 hospital, whereas no patients in the antipsychotic group

and similar to the minimal clinically important were. Similarly, no serious adverse events were reported

difference associated with patient-rated improvement to the ethics committee for the antipsychotics group,

(11·2 points).33 We recorded improvement across compared with two for the CBT group and four for the

measures of symptoms and personal and social combined group (although only one was deemed

recovery, functioning, and quality of life, irrespective treatment related). There is increased opportunity for

of intervention. adverse events to be observed in the patients receiving

Antipsychotics plus CBT was significantly more CBT, because they had weekly contact with trial staff

efficacious than CBT alone (p=0·019), but the difference tasked with reporting adverse effects (the trial therapists).

between antipsychotics plus CBT and antipsychotics By contrast, patients in the antipsychotics group had

alone was not significant (p=0·06). However, because much less frequent contact with trial staff (the trial

this study was a pilot and feasibility trial, it was not research assistants).

powered to reliably detect differences between groups, The number of sessions attended and compliance

and any significant differences should be treated with with homework tasks suggests that CBT was delivered

caution. Efficacy did not differ significantly between the successfully to most participants, although competence

CBT group and the antipsychotic group, which is of CBT delivery and adherence to the treatment protocol

noteworthy given that CBT finished after 24 weeks was not monitored systematically. Antipsychotics were

whereas antipsychotic treatment could last 52 weeks selected on an individual basis, consistent with National

(median duration 44·5 weeks). The absence of any Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance. The

apparent differences between the three groups at four antipsychotics used most frequently in the study

6 weeks is also noteworthy (appendix), because 6 weeks (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone)

is a common length for drug trials. The number of are the four antipsychotics most commonly initiated in

participants with PANSS-rated deterioration was low routine clinical practice in first-episode services in

across all groups at each timepoint, with no suggestion the UK.34 Dose and duration of antipsychotic treatment

that CBT was worse than antipsychotics or combination were at the discretion of the treating clinician and

treatment. Only three early deteriorations (ie, at 6 or patient wishes. One patient’s primary antipsychotic was

12 weeks) were noted, two in the antipsychotics group promazine, which is approved to treat agitation but not

and one in the CBT group. psychosis; the low dose given was insufficient to be

Fewer side-effects were noted in the CBT group than regarded as an effective antipsychotic dose (appendix).

in the antipsychotic group or the combined intervention The mean modal doses of the other primary anti

group. However, this difference is more accounted for by psychotics prescribed were at the low end of the dose

reduction in side-effects over time in the CBT group ranges recommended to treat psychosis, which is

than by increases in side-effects in the antipsychotic and probably because participants were recruited almost

combined groups. This decrease in side-effects in the exclusively from early-intervention services. People with

CBT group could be related to many ANNSERS items first-episode psychosis respond to doses of antipsych

being non-specific (eg, sleep problems, memory and otics lower than those required for multi-episode

attention, loss of libido, loss of energy, and autonomic schizophrenia,29 and are more sensitive to side-effects

symptoms). Such symptoms could be symptoms of a than patients with multi-episode schizophrenia, which

psychotic disorder or a comorbid illness, or could be has led to guidelines recom mending low doses.35,36

antipsychotic side-effects. Some patients in the CBT Nevertheless, the doses of some of the antipsychotics,

group and the combined group were admitted to especially quetiapine, were lower than the corresponding

420 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018

Articles

doses used in the CAFÉ and EUFEST trials in first- Our study mostly involved participants who met

episode psychosis. In most cases in our study, when PANSS-defined criteria for acceptance into early-

duration of antipsychotic treatment was known, the intervention services, whereas EUFEST and CAFÉ only

primary antipsychotic was continued for 6 weeks or included participants with schizophrenia spectrum

longer, suggesting that treatment duration was sufficient diagnoses.

to establish effectiveness. 12 (32%) of the 38 participants Our sample was diagnostically heterogeneous:

who started antipsychotic treatment switched anti 73 participants were recruited from early-intervention

psychotic at least once, implying pers everance to services, which operationally define first-episode psych

identify an effective medication. Overall, use of osis with the PANSS. Therefore, our findings are

antipsychotics was pragmatic and broadly consistent generalisable to early-intervention services only, at least

with clinical practice in early-intervention services and in the UK, and should not be generalised to patients

treatment guidelines. with long-term schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses.

The study had several limitations. The pilot and The design of our study (ie, three active intervention

feasibility trial design and small sample size mean that arms), combined with the fact that most participants

caution should be used when interpreting the statistical received care from early-intervention services, means

tests and significance values. Although only 12% of that we cannot rule out the possibility that recorded

participants received an intervention they were not benefits could be attributable to generic factors such as

allocated to, a reasonable proportion did not take up the good care coordination, engagement, assertive outreach,

offer of allocated interventions, reflecting that in and crisis management, rather than the specific active

clinical practice many people do not comply with treatments. Failure to include the EQ5D means we could

medication regimens,34 and some do not engage with not examine quality-adjusted life-years and cost-

talking therapies. Such rates of non-adherence are effectiveness.

common in drug and psychological therapy trials. The main implication of this trial is that an adequately

Operationalisation of antipsychotic treatment in powered efficacy and effectiveness trial is needed to

terms of target doses, minimal duration of trials, and provide evidence about relative efficacy of antipsychotics

encouraging switching if treatment was unsatisfactory and CBT. In our trial, participants were almost

might have improved the efficacy of drug treatment, exclusively experiencing a first episode of psychosis, so

but higher doses might have led to more side-effects a definitive trial should target this population and

and greater dropout rates. In our trial, medication was recruit via early-intervention services (appendix). A trial

prescribed and dispensed in accordance with normal in people with multiple episode psychotic disorders

clinical practice, as opposed to delivery of medication to would probably not be feasible in generic community

patients and use of regular pill counts, both of which mental health teams, mostly because potential

might improve adherence. The absence of weight gain participants are already prescribed antipsychotics. At

in the antipsychotics group casts doubt on adherence. present, it seems reasonable to support people with

We did not have a standardised operating procedure for psychosis (who do not present immediate risk to

weight measurement that emphasised consistency themselves or others) to make informed choices as

of flooring, and many assessments were done in outlined in the National Institute for Health and Care

participants’ homes. Therefore, weight data could Excellence guidelines,1 which recommend advising

contain errors. Another limitation is that we did not people who want to try psychological interventions

systematically record use of other medications such as alone that such interventions are more effective when

antidepressants or anxiolytics, or measure substance delivered in conjunction with antipsychotic medication,

and alcohol use. but allowing them to try family intervention and CBT

Response rates on the PANSS and the degree of without antipsychotics while agreeing a time to review

improvement on the Clinical Global Impressions scale treatment options, including introduction of anti

were lower in our trial than in previous 52-week psychotics.

randomised controlled trials of antipsychotics in first- Contributors

episode psychosis.29,30 However, data analytic strategies All authors were involved in study design, management, and delivery,

and high attrition in these studies might have increased and contributed to drafting of this Article. APM was the chief

investigator, conceived the study, prepared the protocol, supervised

the risk of bias, which could inflate effects. In EUFEST,30 researchers, had overall responsibility for day-to-day running of the

for example, data obtained before treatment dis- study, interpreted data, led writing of the Article, and is the study

continuation were used in analysis of PANSS outcomes, guarantor. APM, PF, EKM, NH, AS, SEB, and JP-C prepared the

which was likely to have introduced bias given the high treatment protocol and trained and supervised the therapists.

APM, HL, MP, and PMH trained the researchers in use of psychiatric

frequency of discontinuation (33–72%, depending on interviews, and supervised and monitored standards of psychiatric

the specific drug). CAFÉ had very high attrition at interviewing and assessment throughout the trial. APM, PF, ARY, and

52 weeks (67–73%, depending on drug), which probably PMH advised on diagnostic ratings and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

introduced bias.29 Response is also dependent on patient DS, ARY, and PMH advised on medical and pharmacological issues and

liaised with prescribers. HL was the trial manager, supervised and

and illness characteristics, which vary between studies.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 421

Articles

coordinated recruitment, contributed to training of research staff, and 10 Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, et al. Prevalence, incidence and

was responsible for staff management and overall study coordination. mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and

HL, LC, RS, and MP were responsible for maintaining reliability of specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of

assessment procedures and data collection. RE, the trial statistician, 3 211 768 patients and 113 383 368 controls. World Psychiatry 2017;

advised on randomisation and all statistical aspects of the trial, 16: 163–80.

developed the analysis plan, and did the statistical analyses. LD was the 11 Taylor M, Perera U. NICE CG178 psychosis and schizophrenia in

health economist. RB was a service user consultant involved in all adults: treatment and management—an evidence-based guideline?

Br J Psychiatry 2015; 206: 357–59.

aspects of the study.

12 Morrison AP, Birchwood M, Pyle M, et al. Impact of cognitive

Declaration of interests therapy on internalised stigma in people with at-risk mental states.

APM, PF, and SEB deliver training workshops and have written Br J Psychiatry 2013; 203: 140–45.

textbooks about CBT for psychosis, for which they receive fees. 13 Morrison AP, Turkington D, Pyle M, et al. Cognitive therapy for

All authors have done funded research on CBT for psychosis, and RE, people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders not taking

ARY, LD, and PMH have done funded research on antipsychotics. antipsychotic drugs: a single-blind randomised controlled trial.

APM, PF, EKM, NH, AS, SEB, JP-C, and VB deliver CBT in the Lancet 2014; 383: 1395–403.

National Health Service. DS is an expert adviser for the National 14 Goldsmith LP, Lewis SW, Dunn G, Bentall RP. Psychological

Institute of Health and Care Excellence Centre for Guidelines and a treatments for early psychosis can be beneficial or harmful,

board member of the National Collaborating Centre of Mental Health. depending on the therapeutic alliance: an instrumental variable

analysis. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 2365–73.

ARY has received honoraria from Janssen Cilag and Sunovion.

PMH has received honoraria for lecturing or consultancy work from 15 Morrison AP. The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis:

an integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions.

Allergan, Galen, Janssen, Lundbeck, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals,

Behav Cogn Psychother 2001; 29: 257–76.

Otsuka, Sunovion, and Teva, plus conference support from Janssen,

16 Morrison AP. A manualised treatment protocol to guide delivery

Lundbeck and Sunovion. All other authors declare no competing

of evidence-based cognitive therapy for people with distressing

interests.

psychosis: learning from clinical trials. Psychosis 2017;

Acknowledgments 9: 271–81.

This trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research 17 Blackburn IM, James I, Milne D, Baker CA, Standart S, Garland A.

(NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme The revised cognitive therapy scale (CTS-R): psychometric

(Grant Reference Number PB-PG- 1112-29057). The views expressed are properties. Behav Cogn Psychother 2001; 29: 431–46.

those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National 18 Kay S, Fiszbein A, Opler L. The positive and negative syndrome

Health Service, NIHR, the Department of Health, the National Institute scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13: 261–76.

for Health and Care Excellence, or the National Collaborating Centre 19 Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale.

for Mental Health. We thank the Psychosis Research Unit Service User Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983; 67: 361–70.

Reference Group for their contributions to study design and 20 WHO Quality of Life Group. The World Health Organization

development of study-related materials, the Greater Manchester quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general

Clinical Research Network for their support and assistance, and psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998; 46: 1569–85.

David Kingdon and John Norrie, the independent members of our trial 21 Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R.

steering and data monitoring committee. We also thank Elizabeth Pitt Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the

DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale

for acting as a service user consultant for the trial (because of

(SOFAS) to assess routine social funtioning.

unforeseen circumstances, she could not be contacted about this Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2000; 101: 323–29.

acknowledgment).

22 Law H, Neil ST, Dunn G, Morrison AP. Psychometric properties of

References the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR).

1 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and Schizophr Res 2014; 156: 184–89.

schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. London: 23 Guy W. Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville:

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014. US Department of Heath, Education, and Welfare Public Health

2 Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws KR. Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration,

Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: 1976.

systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential 24 Ohlsen R, Williamson R, Yusufi B, et al. Interrater reliability of

bias. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204: 20–29. the Antipsychotic Non-Neurological Side-Effects Rating Scale

3 Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy measured in patients treated with clozapine.

for schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological J Psychopharmacol 2008; 22: 323–29.

rigor. Schizophr Bull 2008; 34: 523–37. 25 Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size

4 Mehl S, Werner D, Lincoln TM. Does cognitive behavior therapy determination. Stat Med 1995; 14: 1933–40.

for psychosis (CBTp) show a sustainable effect on delusions? 26 Law H, Carter L, Sellers R, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial

A meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2015; 6: 1450. comparing antipsychotic medication, to cognitive behavioural

5 Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy therapy to a combination of both in people with psychosis:

and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: rationale, study design and baseline data of the COMPARE trial.

a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 382: 951–62. Psychosis 2017; 9: 193–204.

6 Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM. 27 Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data.

How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? London: John Wiley and Sons, 2002.

A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 28 Leucht S, Kissling W, Davis JM. The PANSS should be rescaled.

14: 429–47. Schizophr Bull 2010; 36: 461–62.

7 Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled 29 McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and

antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the

Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week

Am J Psychiatry 2017; 174: 927–42. comparison. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1050–60.

8 Zhu Y, Li C, Huhn M, Rothe P, et al. How well do patients with 30 Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. Effectiveness of

a first episode of schizophrenia respond to antipsychotics: antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and

a systematic review and meta-analysis. schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial.

Eur Neuropsychopharmacology 2017; 27: 835–44. Lancet 2008; 371: 1085–97.

9 Haddad P, Sharma S. Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics: 31 Leucht S, Kane JM, Etschel E, Kissling W, Hamann J, Engel RR.

differential risk and clinical implications. CNS Drugs 2007; Linking the PANSS, BPRS, and CGI: clinical implications.

21: 911–36. Neuropsychopharmacol 2006; 31: 2318–25.

422 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018

Articles

32 Thwin SS, Hermes E, Lew R, et al. Assessment of the minimum 35 Barnes TR. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological

clinically important difference in quality of life in schizophrenia treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British

measured by the Quality of Well-Being Scale and disease-specific Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2011;

measures. Psychiatry Res 2013; 209: 291–96. 25: 567–620.

33 Hermes EDA, Sokoloff DM, Stroup TS, Rosenheck RA. 36 Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F,

Minimum clinically important difference in the Positive Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic

And Negative Syndrome Scale using data from the CATIE dosing. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167: 686–93.

schizophrenia trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2012; 73: 526–32.

34 Whale R, Harris M, Kavanagh G, et al. Effectiveness of

antipsychotics used in first-episode psychosis: a naturalistic

cohort study. BJPsych Open 2016; 2: 323–29.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 5 May 2018 423

You might also like

- Antipsikotik Vs Behaviour Therapy Pada Pasien PsikotikDocument12 pagesAntipsikotik Vs Behaviour Therapy Pada Pasien PsikotikDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673613622461 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0140673613622461 MainFrancisco Javier RamosNo ratings yet

- Clinical Effectiveness and Acceptability of StructDocument10 pagesClinical Effectiveness and Acceptability of StructArthur AlvesNo ratings yet

- Background: Lancet Psychiatry 2017Document11 pagesBackground: Lancet Psychiatry 2017Manya DhuparNo ratings yet

- RCT - Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - 2017Document10 pagesRCT - Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - 2017RayssaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2215036616303789Document11 pagesPi Is 2215036616303789U of T MedicineNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Clozapine-Resistant Schizophrenia (FOCUS) : An Assessor-Blinded, Randomised Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesCognitive Behavioural Therapy in Clozapine-Resistant Schizophrenia (FOCUS) : An Assessor-Blinded, Randomised Controlled TrialRabiatul AdawiyahNo ratings yet

- Goldstein 2010Document10 pagesGoldstein 2010esckere papas fritasNo ratings yet

- Špela PDFDocument11 pagesŠpela PDFŠpela MiroševičNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Acute Stress DisorderDocument11 pagesTreatment of Acute Stress DisorderKusnanto Penasehat Kpb RyusakiNo ratings yet

- Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of 32 Oral Antipsychotics For The Acute Treatment of Adults With Multi-Episode Schizophrenia PDFDocument13 pagesComparative Efficacy and Tolerability of 32 Oral Antipsychotics For The Acute Treatment of Adults With Multi-Episode Schizophrenia PDFfrancesca_valdiviaNo ratings yet

- 2022 de VriesDocument8 pages2022 de Vriesmvillar15_247536468No ratings yet

- Comparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderDocument8 pagesComparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderAnanda Amanda cintaNo ratings yet

- Sustained Benefit of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Health Anxiety in Medical Patients (CHAMP) Over 8 Years A Randomised-Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesSustained Benefit of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Health Anxiety in Medical Patients (CHAMP) Over 8 Years A Randomised-Controlled TrialJan LAWNo ratings yet

- Paroxetine, Cognitive Therapy or Their Combination in The Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder With and Without Avoidant Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument11 pagesParoxetine, Cognitive Therapy or Their Combination in The Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder With and Without Avoidant Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical TrialAdm Foto MahniteseNo ratings yet

- Meta-Analysis of The Efficacy of Treatments For PTSDDocument10 pagesMeta-Analysis of The Efficacy of Treatments For PTSDJulianaNo ratings yet

- Jiwa 1Document9 pagesJiwa 1Hamidah S.No ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Stroup 2019 Oi 180113Document8 pagesJamapsychiatry Stroup 2019 Oi 180113opanocayNo ratings yet

- We Therell 2009Document10 pagesWe Therell 2009Oslo SaputraNo ratings yet

- Norton 2012Document12 pagesNorton 2012aaron.pozoNo ratings yet

- Edited By: Dr. Javaid Akhtar, MCPS, FCPS, Head Of: Search StrategyDocument3 pagesEdited By: Dr. Javaid Akhtar, MCPS, FCPS, Head Of: Search StrategyKaram Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Gloster Et Al., (2019)Document15 pagesGloster Et Al., (2019)Jonathan PitreNo ratings yet

- Bryant20et20al20 20additive20benefit20of20hypnosis20and20cbtDocument8 pagesBryant20et20al20 20additive20benefit20of20hypnosis20and20cbtita elizabethNo ratings yet

- On Predicting Improvement and Relapse in Generalized Anxiety Disorder Following PsychotherapyDocument19 pagesOn Predicting Improvement and Relapse in Generalized Anxiety Disorder Following PsychotherapyElizaIancuNo ratings yet

- Cuijpers Et Al., (2021)Document11 pagesCuijpers Et Al., (2021)Jonathan PitreNo ratings yet

- Artikel InternasionalDocument15 pagesArtikel InternasionalFitriatul MunawarohNo ratings yet

- Depression TreatmentDocument8 pagesDepression TreatmentAkshay HegdeNo ratings yet

- Rector Et Al-2019-British Journal of Clinical PsychologyDocument18 pagesRector Et Al-2019-British Journal of Clinical PsychologyJulia DGNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument11 pagesArticles: BackgroundNurul AhdiahNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavior Therapy Vs Exposure Therapy in The Treatment of PTSD in RefugeesDocument15 pagesCognitive-Behavior Therapy Vs Exposure Therapy in The Treatment of PTSD in RefugeesAna CristeaNo ratings yet

- TCC Con Fase de Continuación para DepresiónDocument15 pagesTCC Con Fase de Continuación para DepresiónGuillermo Van LooNo ratings yet

- Depresia CazDocument19 pagesDepresia CazBetu SasuNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Anxiety Disorders by Psychiatrists From The American Psychiatric Practice Research NetworkDocument6 pagesTreatment of Anxiety Disorders by Psychiatrists From The American Psychiatric Practice Research NetworkStephNo ratings yet

- Anti Dep and Alzheimers Lancet 2011Document9 pagesAnti Dep and Alzheimers Lancet 2011bcy123No ratings yet

- Effect of Group V Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy in Active-Duty Military Seeking Treatment For Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDocument9 pagesEffect of Group V Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy in Active-Duty Military Seeking Treatment For Posttraumatic Stress DisorderBrandon Gray100% (1)

- Internet-Versus Group-Administered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Panic Disorder in A Psychiatric Setting: A Randomised TrialDocument10 pagesInternet-Versus Group-Administered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Panic Disorder in A Psychiatric Setting: A Randomised TrialSophi RetnaningsihNo ratings yet

- Metaanalisis CBT Vs TauDocument14 pagesMetaanalisis CBT Vs TauIndrawaty SuhuyanliNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Videoconference-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adults With Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic and Meta-Analytic ReviewDocument16 pagesEffectiveness of Videoconference-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adults With Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic and Meta-Analytic ReviewlaiaNo ratings yet

- Evid Based Mental Health 2001 Therapeutics 82Document2 pagesEvid Based Mental Health 2001 Therapeutics 82Fernanda Avila CastroNo ratings yet

- Cannabis and ShizoDocument2 pagesCannabis and ShizoFarah MuthiaNo ratings yet

- Medicine: A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111Document34 pagesMedicine: A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111José Carlos Sánchez RamírezNo ratings yet

- Behavior TherapyDocument29 pagesBehavior TherapyKrisztina MkNo ratings yet

- Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Psychosis (Cacbtp) in PakistanDocument8 pagesPilot Randomised Controlled Trial of Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Psychosis (Cacbtp) in Pakistanzuhrul_baladNo ratings yet

- Patients SchizofreniaDocument3 pagesPatients SchizofreniaArinaDogaruNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Cognitive Therapy in Depressed PatientsDocument14 pagesA Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Cognitive Therapy in Depressed PatientsDragan DjundaNo ratings yet

- The Role of CBT in Relapse Prevention of SchizophreniaDocument2 pagesThe Role of CBT in Relapse Prevention of SchizophreniaKorn IbraNo ratings yet

- Birchwood 2014Document11 pagesBirchwood 2014Lisa MaghfirahNo ratings yet

- (Stanley) Joc90025 - 1460 - 1467Document8 pages(Stanley) Joc90025 - 1460 - 1467niia kurniiasihNo ratings yet

- And Behavioural Stress Management For Severe Health Anxiety: Internet-Delivered Exposure-Based Cognitive-Behavioural TherapyDocument9 pagesAnd Behavioural Stress Management For Severe Health Anxiety: Internet-Delivered Exposure-Based Cognitive-Behavioural TherapyRoxana MălinNo ratings yet

- J Eurpsy 2017 01 367Document2 pagesJ Eurpsy 2017 01 367Joan WuNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument14 pagesArticles: BackgroundCLO GENSANNo ratings yet

- Physical Exercise and iCBT in Treatment of DepressionDocument9 pagesPhysical Exercise and iCBT in Treatment of DepressionCarregan AlvarezNo ratings yet

- PIIS2215036623002584Document12 pagesPIIS2215036623002584Dr. Nivas SaminathanNo ratings yet

- Adherence With Psychotherapy and Treatment Outcomes With Psychogenic Nonepileptic SeizuresDocument6 pagesAdherence With Psychotherapy and Treatment Outcomes With Psychogenic Nonepileptic SeizuresNely M. RosyidiNo ratings yet

- D. Barlow - Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment For Panic Disorder Current StatusDocument16 pagesD. Barlow - Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment For Panic Disorder Current StatusArmando ValladaresNo ratings yet

- Depression and Anxiety - 2022 - Gutner - A Pilot Randomized Effectiveness Trial of The Unified Protocol in Trauma ExposedDocument11 pagesDepression and Anxiety - 2022 - Gutner - A Pilot Randomized Effectiveness Trial of The Unified Protocol in Trauma ExposedCristina Alarcón RuedaNo ratings yet

- Artículo Grupo 3Document11 pagesArtículo Grupo 3pepeluchovelezquezadaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy For Treatment Anxiety DisordersDocument10 pagesEfficacy For Treatment Anxiety DisordersAnderson GaldinoNo ratings yet

- A Study of Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patients PDFDocument34 pagesA Study of Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patients PDFIrdha Nasta KurniaNo ratings yet

- Your Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022From EverandYour Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022No ratings yet

- Indonesia Development Update A Year of Covid-19: A Long Road To Recovery and Acceleration of Indonesia's DevelopmentDocument19 pagesIndonesia Development Update A Year of Covid-19: A Long Road To Recovery and Acceleration of Indonesia's Developmentlee suk moNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) DiagnosisDocument6 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Diagnosiszuhrul_baladNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Sampaiojunior 2017 Oi 170097Document9 pagesJamapsychiatry Sampaiojunior 2017 Oi 170097zuhrul_balad100% (1)

- A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Lithium Plus Valproic Acid Versus Lithium Plus Carbamazepine in Young Patients With Type 1 Bipolar Disorder: The LICAVAL StudyDocument9 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Lithium Plus Valproic Acid Versus Lithium Plus Carbamazepine in Young Patients With Type 1 Bipolar Disorder: The LICAVAL Studyzuhrul_baladNo ratings yet

- Contact Tracing Assessment of COVID-19 Transmission DynamicsDocument8 pagesContact Tracing Assessment of COVID-19 Transmission Dynamicszuhrul_baladNo ratings yet