Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antipsikotik Vs Behaviour Therapy Pada Pasien Psikotik

Uploaded by

Dewi NofiantiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antipsikotik Vs Behaviour Therapy Pada Pasien Psikotik

Uploaded by

Dewi NofiantiCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Antipsychotic drugs versus cognitive behavioural therapy

versus a combination of both in people with psychosis:

a randomised controlled pilot and feasibility study

Anthony P Morrison, Heather Law, Lucy Carter, Rachel Sellers, Richard Emsley, Melissa Pyle, Paul French, David Shiers, Alison R Yung,

Elizabeth K Murphy, Natasha Holden, Ann Steele, Samantha E Bowe, Jasper Palmier-Claus, Victoria Brooks, Rory Byrne, Linda Davies,

Peter M Haddad

Summary

Background Little evidence is available for head-to-head comparisons of psychosocial interventions and pharmacological Lancet Psychiatry 2018

interventions in psychosis. We aimed to establish whether a randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural Published Online

therapy (CBT) versus antipsychotic drugs versus a combination of both would be feasible in people with psychosis. March 28, 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S2215-0366(18)30096-8

Methods We did a single-site, single-blind pilot randomised controlled trial in people with psychosis who used services

See Online/Comment

in National Health Service trusts across Greater Manchester, UK. Eligible participants were aged 16 years or older; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

met ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder, or met the entry criteria for an S2215-0366(18)30123-8

early intervention for psychosis service; were in contact with mental health services, under the care of a consultant Division of Psychology and

psychiatrist; scored at least 4 on delusions or hallucinations items, or at least 5 on suspiciousness, persecution, or Mental Health

grandiosity items on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); had capacity to consent; and were help- (Prof A P Morrison ClinPsyD,

H Law PhD, L Carter PhD,

seeking. Participants were assigned (1:1:1) to antipsychotics, CBT, or antipsychotics plus CBT. Randomisation was R Sellers PhD, M Pyle PhD,

done via a secure web-based randomisation system (Sealed Envelope), with randomised permuted blocks of 4 and 6, Prof P French PhD,

stratified by gender and first episode status. CBT incorporated up to 26 sessions over 6 months plus up to four booster D Shiers MBChB,

sessions. Choice and dose of antipsychotic were at the discretion of the treating consultant. Participants were followed Prof A R Yung PhD,

J Palmier-Claus PhD, R Byrne PhD,

up for 1 year. The primary outcome was feasibility (ie, data about recruitment, retention, and acceptability), and the Prof P M Haddad MD), Division

primary efficacy outcome was the PANSS total score (assessed at baseline, 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks). Non-neurological of Population Health, Health

side-effects were assessed systemically with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale. Primary Services Research and Primary

analyses were done by intention to treat; safety analyses were done on an as-treated basis. The study was prospectively Care (Prof R Emsley PhD,

Prof L Davies PhD), and

registered with ISRCTN, number ISRCTN06022197. Manchester Academic Health

Science Centre Clinical Trials

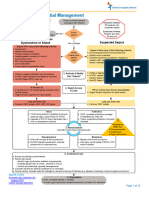

Findings Of 138 patients referred to the study, 75 were recruited and randomly assigned—26 to CBT, 24 to Unit (Prof R Emsley), University

of Manchester, Manchester

antipsychotics, and 25 to antipsychotics plus CBT. Attrition was low, and retention high, with only four withdrawals

Academic Health Science

across all groups. 40 (78%) of 51 participants allocated to CBT attended six or more sessions. Of the 49 participants Centre, Manchester, UK; and

randomised to antipsychotics, 11 (22%) were not prescribed a regular antipsychotic. Median duration of total Greater Manchester Mental

antipsychotic treatment was 44·5 weeks (IQR 26–51). PANSS total score was significantly reduced in the combined Health NHS Foundation Trust,

Manchester, UK

intervention group compared with the CBT group (–5·65 [95% CI –10·37 to –0·93]; p=0·019). PANSS total scores did

(Prof A P Morrison, H Law,

not differ significantly between the combined group and the antipsychotics group (–4·52 [95% CI –9·30 to 0·26]; L Carter, R Sellers, M Pyle,

p=0·064) or between the antipsychotics and CBT groups (–1·13 [95% CI –5·81 to 3·55]; p=0·637). Significantly fewer P French, D Shiers, Prof A R Yung,

side-effects, as measured with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale, were noted in the CBT E K Murphy ClinPsyD,

N Holden DClinPsy, A Steele PhD,

group than in the antipsychotics (3·22 [95% CI 0·58 to 5·87]; p=0·017) or antipsychotics plus CBT (3·99 [95% CI

S E Bowe DClinPsy,

1·36 to 6·64]; p=0·003) groups. Only one serious adverse event was thought to be related to the trial (an overdose of J Palmier-Claus, V Brooks RMN,

three paracetamol tablets in the CBT group). R Byrne, Prof P M Haddad)

Correspondence to:

Interpretation A head-to-head clinical trial of CBT versus antipsychotics versus the combination of the two is feasible Dr Tony Morrison, Psychosis

Research Unit, Greater

and safe in people with first-episode psychosis.

Manchester Mental Health NHS

Foundation Trust, Manchester,

Funding National Institute for Health Research. M25 3BL, UK

tony.morrison@gmmh.nhs.uk

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction or other psychoses.1 Many clinical guidelines, therefore,

Schizophrenia and psychosis are associated with sub suggest that people with psychosis should be offered

stantial personal, social, and economic costs. High- both antipsychotics and CBT (as well as family

quality evidence from clinical trials shows that both interventions) and should be involved in collaborative

antipsychotics and cognitive behavioural (CBT) therapy decisions about treatment options.1 However, neither

can be helpful to adults with diagnoses of schizophrenia antipsychotics nor CBT are effective for everyone, and

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8 1

Articles

Research in context

Evidence before this study randomly assigned to psychological treatment or

We searched PubMed with the terms “schizophrenia”, pharmacological treatment, or both, is possible. Our findings

“psychosis”, “psychological therapy”, “psychosocial suggest that antipsychotics, CBT, and the combination of the

intervention”, “CBT”, “antipsychotic” and “neuroleptic” for two are acceptable, safe, and helpful treatments for people

articles published in any language up to Jan 30, 2018. with early psychosis, but could have different cost–benefit

Although several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have profiles.

shown robust evidence that antipsychotics are superior to

Implications of all the available evidence

placebo and that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for

Our preliminary findings seem consistent with guidelines

psychosis in addition to antipsychotics is superior to

that recommend informed choices and shared decision

treatment as usual, we identified no randomised controlled

making about treatment options for early psychosis on the

trials in which a head-to-head comparison of CBT and

basis of cost–benefit profiles. An adequately powered efficacy

antipsychotics was done. A 2012 Cochrane review concluded

and effectiveness trial is now needed to test hypotheses

that no usable data were available to establish the relative

about superiority (eg, antipsychotics plus CBT vs

efficacy of antipsychotic medication and psychosocial

antipsychotics alone or CBT alone) and non-inferiority

interventions in early episode psychosis.

(eg, antipsychotics vs CBT).

Added value of this study

Our pilot and feasibility trial showed that a methodologically

rigorous clinical trial in which participants with psychosis are

the individual cost–benefit ratios of such treatments concern, in view of the increased cardiovascular mortality

(ie, the balance between efficacy and adverse effects) vary in people with psychosis compared with the general

substantially, both between and within individuals. population.10 Adverse effects of CBT in psychosis have

Meta-analyses2–4 of randomised controlled trials of CBT, not been well studied.2 Potential side-effects, such as

added to antipsychotics, for psychosis have shown effect stigma and deterioration of mental state,11 were not

sizes for both total symptoms and positive symptoms in detected in clinical trials of CBT for people with psychotic

the small-to-moderate range (generally 0·3–0·4 relative to experiences. Rather, CBT resulted in significant

treatment as usual, although the effect size is smaller reductions in the frequency of these side-effects.12,13

when lower quality trials are excluded). Meta-analyses5,6 of However, CBT delivered in the context of a poor

antipsychotics compared with placebo also show therapeutic relationship could be harmful.14

moderate benefits in terms of total and positive Whereas most evidence for the efficacy of CBT for

symptoms. The most comprehensive meta-analysis7 in psychosis is from randomised controlled trials in which

chronic schizophrenia showed a standardised effect size CBT was provided as an adjunct to antipsychotics

for total symptoms of 0·47 (95% CI 0·42–0·51). Although (ie, a combination of both vs antipsychotics alone),

CBT and antipsychotics are better than comparators preliminary evidence suggests that CBT might be helpful

(treatment as usual and placebo, respectively), the for people with psychosis who are not taking anti

proportion of individuals who achieve a clinically psychotics.13 No data for the relative head-to-head efficacy

meaningful benefit is moderate. For example, a meta- or acceptability of CBT and antipsychotics in schizo

analysis7 showed that 51% of multi-episode patients had phrenia are available. We investigated the feasibility of

at least a minimal response (≥20% reduction in symptoms doing a three-group randomised controlled trial of CBT,

as measured on the Positive and Negative Syndrome antipsychotics, and a combination of CBT and anti

Scale [PANSS] or Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale), and psychotics in people with psychosis.

23% had a good response (≥50% reduction in symptoms),

to antipsychotics. By comparison, in first-episode Methods

psychosis, 81% of patients had at least a minimal Study design and participants

response, and 52% had a good response, to antipsychotics.8 We did a single-blind, randomised, controlled pragmatic

The authors of a meta-analysis2 claim that conclusions pilot and feasibility trial between April 1, 2014, and

about the efficacy of CBT have been exaggerated, given June 30, 2017 in four specialist mental health National

that most large, robust trials have not shown significant Health Service trusts in Greater Manchester, UK. Eligible

effects at end of treatment, and that effect sizes are participants were aged 16 years or older; met ICD-10

reduced overall if only studies of high quality are included criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or

in meta-analyses. delusional disorder, or met the entry criteria for an

Antipsychotics are associated with a wide range of early intervention for psychosis service (operationally

adverse effects.5,9 Metabolic effects are of particular defined with the PANSS), because most individuals with

2 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8

Articles

first-episode psychosis will receive care from specialist practice, and thus there were no restrictions on the

teams, as recommended by National Institute for Health antipsychotics that could be selected or their doses.

and Care Excellence guidelines; were in contact with Clinicians could switch antipsychotics and adjust doses

mental health services, under the care of a consultant as clinically indicated, but were encouraged to continue

psychiatrist; scored at least 4 on the PANSS delusions or antipsychotic treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks,

hallucinations items, or at least 5 on suspiciousness, and preferably for at least 26 weeks. Participants

persecution, or grandiosity items; and had to have the allocated to the combined treatment group were offered

capacity to consent and also had to be help-seeking. CBT and antipsychotic medications as described for the

Exclusion criteria were receipt of antipsychotic monotherapy groups.

medication or structured CBT with a qualified therapist Clinicians could prescribe drugs other than anti

within the past 3 months, moderate-to-severe learning psychotics, including antidepressants, anxiolytics, and

disabilities, organic impairment, a score of 5 or more on hypnotics, for all participants. Participants were offered

the PANSS conceptual disorganisation item, and a monitoring assessments at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks,

primary diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependence; and 52 weeks. At each assessment, we measured weight,

patients who were an immediate risk to themselves or blood pressure, HbA1c concentrations, fasting glucose

others, and those who did not speak English were also concentrations, and fasting lipids (ie, total cholesterol,

excluded. The PANSS was administered by a research LDL, HDL, triglycerides and prolactin concentrations).

assistant in the participant’s home or a suitable clinical To allay concerns about the safety of withholding

service to establish eligibility, which was confirmed by a antipsychotics medication in the CBT group, trial

qualified clinician. Our trial protocol was approved by the procedures included monitoring for deterioration. Any

National Research Ethics Service of the UK’s National participant randomly assigned to either CBT alone or

Health Service (14/NW/0041). All participants provided antipsychotics alone could be moved to the combined

written informed consent.

138 people screened for eligibility

Randomisation and masking

Participants were recruited via care coordinators,

consultant psychiatrists, and other mental health staff 63 not eligible

within participating mental health National Health 36 did not meet inclusion criteria

22 declined to participate

Service trusts. Eligible participants were then randomly 5 had other reasons

assigned (1:1:1) to antipsychotics, CBT, or antipsychotics

plus CBT via a secure web-based randomisation system

(Sealed Envelope) operated by the trial administrator. We 75 randomly assigned

used randomised permuted blocks of 4 and 6, stratified

by gender and first episode status. Randomisation at the

individual level was independent and concealed, with all 26 allocated to cognitive 24 allocated to antipsychotics 25 allocated to cognitive

assessors masked to group allocation. Allocation was behavioural therapy behavioural therapy and

subsequently made known to the trial manager, trial antipsychotics

administrator, and therapists. Participants and their care

team were informed of the allocation by letter. 20 completed 6-week assessment 22 completed 6-week assessment 20 completed 6-week assessment

6 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 4 missed the assessment

Procedures 1 withdrew 1 withdrew

Participants allocated to CBT were offered up to

26 sessions of therapy based on a specific cognitive 23 completed 12-week 22 completed 12-week 20 completed 12-week

model15 during a 6-month treatment window. Up to assessment assessment assessment

3 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 4 missed the assessment

four optional booster sessions were available during 1 withdrew 1 withdrew

the subsequent 6 months. Therapy was individualised

and problem focused. Permissible interventions were

described in the manualised treatment protocol.16 Therapy 22 completed 24-week 22 completed 24-week 20 completed 24-week

assessment assessment assessment

sessions were usually offered weekly and delivered by 3 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment

appropriately qualified psychological therapists. Fidelity 1 withdrew 1 withdrew 2 withdrew

to protocol was ensured by weekly supervision and

regular rating of recorded sessions with the Cognitive

21 completed 52-week 22 completed 52-week 20 completed 52-week

Therapy Scale–Revised.17 assessment assessment assessment

Participants allocated to antipsychotics were pre 4 missed the assessment 1 missed the assessment 3 missed the assessment

scribed medication by their responsible psychiatrist. 1 withdrew 1 withdrew 2 withdrew

Treatment was begun as soon as possible after

randomisation. Prescribing mirrored standard clinical Figure: Trial profile

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8 3

Articles

treatment group if deterioration in mental state led to

Antipsychotics (n=24) CBT (n=26) Antipsychotics plus

CBT (n=25) involuntary hospitalisation, or if there was a greater

than 25% deterioration in PANSS scores at the 6-week

Age, years 23·21 (4·97) 23·19 (6·32) 24·44 (6·86)

assessment or a greater than 12·5% deterioration in

Sex

PANSS scores at the 12-week assessment.

Male 13 (54%) 16 (62%) 14 (56%)

Female 11 (46%) 10 (38%) 11 (44%)

Outcomes

First-episode psychosis: 24:0 24:2 25:0

multiple episode

The primary outcome was feasibility, which was

psychosis operationalised in terms of referral rates, recruitment,

Duration of untreated 37·33 (44·41) 44·48 (52·30) 39·43 (35·76) retention or attrition, acceptability of treatment,

psychosis, weeks attendance at sessions, adherence to homework, and

PANSS compliance with medication. The primary effectiveness

Total 70·17 (10·12) 70·50 (8·12) 70·76 (8·45) outcome was total score on PANSS18—a 30-item,

Positive 23·04 (4·60) 23·15 (4·63) 21·92 (3·63) semi-structured interview assessing dimensions of

Negative 16·17 (5·72) 15·50 (4·10) 15·24 (5·17) psychosis symptoms rated on a seven-point scale

Disorganised 16·25 (2·60) 17·15 (3·65) 17·8 (4·27) between 1 (absent) and 7 (severe)—which was assessed at

Excitement 18·25 (4·35) 17·85 (3·86) 17·4 (4·14) baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 52 weeks.

Emotional Distress 25·46 (5·00) 25·31 (3·83) 26·28 (3·47) Secondary clinical outcomes were depression and anxiety

Questionnaire about 38·71 (9·23) 40·13 (9·33)* 41·8 (11·79) (assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression

Process of Recovery Scale19), quality of life (assessed with the WHO Quality of

HADS† Life20), social functioning (assessed with the Personal and

Total 41·05 (5·49) 37·54 (5·42) 36·36 (6·76) Social Performance scale21), user-defined recovery

Anxiety 21·96 (2·62) 20·50 (3·32) 19·36 (3·89) (measured with the Questionnaire about the Process of

Depression 19·05 (4·87) 17·38 (3·32) 17·28 (5·55) Recovery22), and results on the Clinical Global

WHO quality of life score‡ 67·03 (14·99) 68·66 (13·41) 70·18 (15·41) Impressions of symptom severity and improvement

Personal and Social 52·67 (13·83) 57·38 (12·04) 58·16 (11·1) scale.23 Instruments were administered by research

Performance Scale assistants trained in their use to achieve a good level

CGI of inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation

Participant version 4·91 (0·97)§ 4·42 (0·99) 4·38 (1·54) coefficient 0·902).

Clinician version 4·13 (0·74) 4·08 (0·63) 4·04 (0·68) Service use, diagnosis, and antipsychotic prescribing

ANNSERS were recorded via review of case notes. Duration of

Number of side-effects 9·96 (4·72), 24 8·88 (3·77), 26 9·16 (4·69), 25 antipsychotic treatment for each participant was based on

Total 13·92 (7·05), 24 12·12 (6·55), 26 12·28 (6·61), 25 all regular antipsychotics prescribed and was not restricted

Cholesterol to the primary antipsychotic (ie, the antipsychotics

Total (mmol/L) 4·54 (0·91), 20 4·08 (0·82), 15 4·45 (0·93), 16 prescribed for the longest during the study). Non-

HDL (mmol/L) 1·34 (0·35), 20 1·13 (0·30), 15 1·38 (0·40), 15 neurological side-effects were assessed systemically with

Total/HDL 3·57 (0·94), 20 3·5 (0·86), 15 3·35 (0·93), 15 the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating

LDL (mmol/L) 2·58 (0·78), 15 2·33 (0·67), 12 2·46 (0·68), 14 Scale.24 At 6 months, we obtained self-report data for

Triglycerides (mmol/L) 1·15 (0·39), 16 1·27 (0·64), 12 1·12 (0·45), 14 antipsychotic adherence in the past month on a visual

Prolactin (mU/L) 183·06 (89·71), 17 187·07 (63·33), 15 198·5 (81·78), 14 analogue scale. At the 52-week visit, we surveyed

Glucose (mmol/L) 6·27 (6·96), 18 5·32 (2·41), 15 4·14 (0·55), 15 participants’ opinions on their preferences and views of

measures used in the study to inform choice of measures

Data are mean (SD); mean (SD), number of observations; or n (%), unless otherwise specified. CBT=cognitive for a definitive trial.

behavioural therapy. PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

CGI=Clinical Global Impressions of Symptom Severity and Improvement Scale. ANNSERS= Antipsychotic After the original ethical approval for the trial in

Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale. *n=25. †n=23 in the antipyschotics group and 24 in the CBT group. February, 2014, a substantial protocol amendment was

‡n=25 in the CBT group and 24 in the antipsychotics plus CBT group. §n=22. made (and approved on July 7, 2014): the lower age limit

Table 1: Baseline characteristics was changed from 18 years to 16 years, being an inpatient

was removed as an exclusion criterion, posing an

immediate risk to self or others was introduced as an

treatment group if their mental state declined during exclusion criterion, and the randomisation timeframe

the trial (this procedure was detailed in the standard was amended from 2 working days to 5 working days.

operating procedures for the study and was presented to Other minor amendments included the addition of

the Research Ethics Committee and clinicians who service user and clinician surveys to gather information

referred to the study). Participants who experienced about the feasibility of recruitment. We had originally

such deterioration remained in the trial, and the proposed that the recruitment window would be variable,

assessment schedule was maintained. Participants were with participants recruited in the first 22 months

also given the option to move into the combined receiving a full 6 months’ follow up and participants

4 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8

Articles

recruited thereafter offered assessments up to the end of

Randomly assigned treatment group Total

treatment. However, we agreed a no-cost extension with

the funder, and were thus able to complete 12-month Antipsychotics CBT Antipsychotics

(n=24) (n=26) plus CBT (n=25)

follow-up visits for all participants. We also originally

proposed that economic analyses would explore the costs Treatment received

of health and social care and quality-adjusted life years Antipsychotics 15 2 4 21

from a broadly societal perspective. However, the EQ5D CBT 0 15 5 20

was erroneously omitted from our assessment battery, Antipsychotics 1 6 14 21

plus CBT

meaning that such analyses were not possible.

Neither 8 3 2 13

Statistical analysis CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy.

The sample size was based on recommendations for

Table 2: Participants’ randomly assigned treatment vs treatment received

obtaining reliable sample size estimates in pilot and

feasibility studies,25 which suggested that 75 patients

would be needed (ie, 25 in each group), with the aim of had multiple previous episodes and were recruited from

achieving usable data for 60 participants across the community mental health services. Most participants did

three groups, allowing for a dropout rate of 20%.26 not have diagnoses in their medical records at baseline.

Primary analysis was by intention to treat. We fitted The most common entry was first-episode psychosis, and

random intercept models with summed scores as the most common formal ICD-10 diagnosis was F29

dependent variables, allowing for attrition and the unspecified non-organic psychosis. Participants from ten

variable follow-up times introduced by trial design. of the 22 participating clinical teams (appendix) were

Covariates were sex, age, time, and the baseline value of randomly assigned. Retention was reasonable, with only

the relevant outcome measure (first episode status, as a four withdrawals and low attrition, which were balanced

stratification factor, should have been included, but across the groups (figure). Nine (12%) partial blind

because only two participants were not having their first breaks (ie, only one treatment was revealed) and

episode of psychosis, age was a more appropriate five (7%) full blind breaks (ie, actual randomly assigned

covariate). The use of these models allowed for analysis group was revealed) were reported by research assistants.

of all available data, on the assumption that data were Four of the full blind breaks were in the antipsychotic

missing at random,27 conditional upon covariates. All arm, and one was in the combined arm. Only 3 (1%) of

treatment effects reported are estimates of the effects 256 follow-up assessments were done by an unmasked

common to all follow-up times (essentially, repeated assessor (the blind was broken during the assessment).

measures ANCOVAs). Because safety and unwanted All three of these assessments were then scored by a

effects should be analysed on the basis of the most masked rater, and consensus was reached on ratings.

accurate information, these results are reported with an Thus, no assessments were done without rater masking

as-treated rather than an intention-to-treat approach. As- Participants who were assigned to CBT (either mono

treated was defined with our predefined minimum therapy or in the combined group) received a mean of

dose criteria for antipsychotics (ie, at least 6 weeks at 14·39 sessions (SD 9·12; range 0–26) within 6 months,

a therapeutic dose) and CBT (at least six sessions). with each session lasting around an hour (additional

We used Stata (version 14.2) for all analyses. This booster sessions were also offered as appropriate).

trial was prospectively registered with ISRCTN 40 (78%) of 51 participants attended six or more sessions,

(number ISRCTN06022197). and only one participant (2%) attended no sessions. Home

work com pliance was good for both participants and

Role of the funding source therapists: 404 (73%) of 557 participant between-session

The funder had no role in study design; data collection, tasks and 396 (89%) of 445 therapist between-session tasks

analysis, or interpretation; or writing of the Article. The were completed.

corresponding author and RE had access to all study data, Of the 49 participants assigned to antipsychotics (either

and the corresponding author had final responsibility for alone or in combination with CBT), 11 (22%) were not

the decision to submit for publication. prescribed a regular antipsychotic for various reasons,

including five participants who declined to take an

Results antipsychotic despite consenting to enter the trial. The

Between May 1, 2014 and Aug 30, 2016, we recruited primary antipsychotics prescribed most frequently were

75 participants, 26 to CBT, 24 to antipsychotics, and 25 to aripiprazole (n=14), olanzapine (n=10), and quetiapine

antipsychotics plus CBT (figure; table 1). The referral to (n=10), as chosen by the treating psychiatrist in the

recruitment rate was roughly 2:1, with only 22 (16%) of participants’ clinical care team (appendix). 12 (32%) of

138 referred patients declining to participate. 73 patients the 38 participants treated with antipsychotics switched

were experiencing first-episode psychosis and recruited antipsychotics at least once. 34 (92%) of 37 participants

from early-intervention services; the other two patients who commenced antipsychotic treatment were

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8 5

Articles

Antipsychotics CBT (n=26) Antipsychotics plus Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

(n=24) CBT (n=25)

CBT vs antipsychotics CBT vs antipsychotics Antipsychotics vs

plus CBT antipsychotics plus CBT

Total ·· ·· ·· –1·13 (2·39; –5·81 to –5·65 (2·41; –10·37 to –4·52 (2·44; –9·30 to

3·55); 0·637 –0·93); 0·019 0·26); 0·064

Week 0 70·13 (10·11), 24 70·35 (8·03), 26 70·76 (8·46), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 64·05 (11·39), 22 64·85 (7·85), 20 64·70 (9·74), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 60·81 (16·52), 21 63·74 (7·73), 23 58·40 (14·51), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 61·09 (14·44), 22 60·50 (8·74), 22 53·77 (12·54), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 56·77 (14·10), 22 58·14 (11·68), 21 57·40 (13·58), 20 ·· ·· ··

Positive ·· ·· ·· –1·16 (1·14; –3·40 to –2·02 (1·15; –4·27 to –0·86 (1·17; –3·15 to

1·09); 0·312 0·24); 0·080 1·43); 0·462

Week 0 23·04 (4·60), 24 23·15 (4·63), 26 21·92 (3·63), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 19·36 (5·44), 22 21·00 (4·38), 20 20·10 (4·41), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 19·19 (7·72), 21 21·00 (4·72), 23 17·40 (5·65), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 17·81 (6·85), 21 18·18 (4·81), 22 15·23 (5·31), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 18·18 (6·52), 22 17·90 (5·92), 21 16·80 (6·05), 20 ·· ·· ··

Negative ·· ·· ·· –1·25 (0·78; –2·78 to –2·31 (0·79; –3·85 to –1·06 (0·79; –2·61,

0·28); 0·110 –0·77); 0·003 0·49); 0·178

Week 0 16·17 (5·72), 24 15·50 (4·10), 26 15·24 (5·17), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 14·64 (5·06), 22 15·05 (3·52), 20 13·90 (4·85), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 14·00 (4·32), 21 14·83 (3·10), 23 13·00 (5·23), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 14·14 (5·47), 22 14·91 (4·72), 22 12·41 (4·60), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 12·73 (4·58), 22 14·62 (4·52), 21 12·80 (3·68), 20 ·· ·· ··

Disorganised ·· ·· ·· –0·19 (0·77; –1·69 to –0·85 (0·77; –2·36 to –0·66 (0·80; –2·22 to

1·32); 0·809 0·66); 0·273 0·90); 0·408

Week 0 16·25 (2·59), 24 17·15 (3·65), 26 17·80 (4·27), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 15·77 (3·18), 22 16·8 (2·91), 20 17·50 (4·01), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 15·19 (4·96), 21 16·39 (3·37), 23 16·25 (4·10), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 15·10 (3·86), 21 15·50 (3·53), 22 14·50 (3·78), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 14·82 (3·67), 22 15·67 (3·73), 21 15·80 (4·25), 20 ·· ·· ··

Excitement ·· ·· ·· –0·45 (0·75; –1·91 to –0·80 (0·75; –2·27 to –0·35 (0·76; –1·84 to

1·02); 0·549 0·67); 0·286 1·13); 0·641

Week 0 18·25 (4·35), 24 17·85 (3·86), 26 17·4 (4·14), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 15·95 (4·09), 22 15·90 (3·93), 20 15·75 (4·05), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 15·52 (4·77), 21 15·52 (3·16), 23 14·35 (4·97), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 14·77 (3·37), 22 14·45 (3·40), 22 12·86 (4·36), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 13·41 (4·07), 22 13·62 (2·89), 21 13·80 (4·26), 20 ·· ·· ··

Emotional ·· ·· ·· 0·0 (1·11; –2·17 to –1·93 (1·12; –4·12 to –1·93 (1·13; –4·15 to

distress 2·18); 0·999 0·26); 0·084 0·29); 0·088

Week 0 25·46 (5·00), 24 25·31 (3·83), 26 26·28 (3·47), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 22·55 (5·21), 22 21·50 (4·27), 20 23·10 (3·93), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 21·38 (6·91), 21 22·48 (4·31), 23 19·60 (5·74), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 21·55 (5·75), 22 20·95 (3·70), 22 17·50 (5·49), 22 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 19·86 (6·12), 22 19·10 (5·49), 21 20·10 (5·08), 20 ·· ·· ··

Data are mean (SD), number of observations, unless otherwise specified. The effects are common to all follow-up times and are analysed by intention to treat. CBT=cognitive

behavioural therapy.

Table 3: Outcomes on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

prescribed their primary antipsychotic for 6 weeks or Self-reported data for medication adherence were

more (duration was not captured for one participant). available at 6 months for 42 (86%) of the 49 participants

The median duration of total antipsychotic treatment (86%) assigned to antipsychotics. 29 participants (69%)

was 44·5 weeks (IQR 26–51; range 2–52). 28 (78%) of reported that they were taking an antipsychotic at that

36 participants with accurate duration data were taking timepoint, among whom mean adherence was

antipsychotic medication at the end of the study. 77% (SD 29·19, range 0–100; on a scale on which

6 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8

Articles

Antipsychotics (n=24) CBT (n=26) Combination (n=25) Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

CBT vs CBT vs antipsychotics Antipsychotics vs

antipsychotics plus CBT antipsychotics plus CBT

QPR ·· ·· ·· –0·93 (2·97; –6·76 4·01 (3·14; –2·15 4·94 (3·05; –1·03 to

to 4·90); 0·754 to 10·17); 0·202 10·91); 0·105

Week 0 38·71 (9·23), 24 40·13 (9·33), 25 41·8 (11·79), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 44·86 (14·99), 22 47·81 (8·86), 21 52 (14·05), 18 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 48·55 (14·73), 22 51·62 (9·25), 21 49·88 (11·04), 17 ·· ·· ··

HADS

Total ·· ·· ·· –0·60 (1·98; –4·48 –2·93 (2·03; –6·90 –2·32 (1·99; –6·22

to 3·27); 0·761 to 1·04); 0·148 to 1·56); 0·241

Week 0 41·05 (5·49), 23 37·54 (5·42), 24 36·36 (6·76), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 35·55 (7·69), 22 35·36 (12·61), 22 30·37 (9·28), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 34·27 (9·08), 22 32·14 (6·96), 21 30·35 (6·98), 17 ·· ·· ··

Anxiety ·· ·· ·· 0·62 (1·28; –1·89 –1·34 (1·32; –3·92 to –1·96 (1·30; –4·50

to 3·14); 0·627 1·25); 0·310 to 0·58); 0·131

Week 0 21·96 (2·62), 23 20·5 (3·32), 24 19·36 (3·89), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 19·36 (4·51), 22 19·18 (10·80), 22 15·65 (5·98), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 18·73 (5·03), 22 17·29 (4·64), 21 15·67 (4·89), 18 ·· ·· ··

Depression ·· ·· ·· –0·14 (1·20; –2·49 –1·60 (1·27; –4·08 to –1·46 (1·20; to –3·82

to 2·20); 0·905 0·88); 0·206 to 0·90); 0·226

Week 0 19·05 (4·87), 23 17·38 (3·32), 24 17·28 (5·55), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 16·27 (5·84), 22 15·18 (3·81), 22 13·42 (5·83), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 14·91 (5·52), 22 14·05 (4·2), 21 14·94 (5·36), 17 ·· ·· ··

WHO quality of ·· ·· ·· 0·62 (3·20; –5·65 5·82 (3·37; –0·78 5·21 (3·39; –1·43

life score to 6·88); 0·847 to 12·42); 0·084 to 11·84); 0·124

Week 0 67·03 (14·99), 24 68·66 (13·41), 25 70·18 (15·41), 24 ·· ·· ··

Week 6 72·5 (19·84), 22 76·78 (14·79), 18 77·82 (14·06), 17 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 77·29 (21·31), 21 79·29 (16·59), 21 85·83 (17·59), 18 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 79·15 (20·95), 20 79·10 (14·03), 21 89·06 (18·87), 18 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 81·36 (20·02), 22 83·81 (15·23), 21 82·93 (19·17), 15 ·· ·· ··

PSP ·· ·· ·· 3·18 (4·18; –5·02 2·17 (4·27; –6·19 –1·01 (4·24; –9·32 to

to 11·38); 0·448 to 10·53); 0·611 7·30); 0·812

Week 0 52·67 (13·83), 24 57·38 (12·04), 26 58·16 (11·1), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 63·95 (18·53), 22 60·05 (10·51), 22 62·48 (17·47), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 60·45 (17·61), 22 60·95 (12·93), 21 61 (16·47), 20 ·· ·· ··

CGI

Clinician ·· ·· ·· –0·16 (0·28; –0·70 –0·64 (0·29; 1·20 –0·48 (0·28; –1·03 to

to 0·38); 0·569 to –0·08); 0·026 0·07); 0·087

Week 0 4·13 (0·74), 24 4·08 (0·63), 26 4·04 (0·68), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 3·32 (1·17), 22 3·45 (0·91), 22 2·86 (1·06), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 3·23 (1·11), 22 3·38 (1·07), 21 3·00 (1·08), 20 ·· ·· ··

Patients ·· ·· ·· 0·35 (0·41; –0·44 –0·29 (0·42; 1·11 –0·65 (0·42; –1·46

to 1·15); 0·385 to 0·52); 0·482 to 0·17); 0·119

Week 0 4·91 (0·97), 22 4·42 (0·99), 26 4·38 (1·54), 25 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 4·33 (1·56), 21 3·71 (1·23), 21 3·20 (1·54), 20 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 3·91 (1·48), 22 3·50 (1·50), 20 3·94 (1·59), 18 ·· ·· ··

Clinician – ·· ·· ·· 0·05 (0·31; –0·56 –0·53 (0·32; –1·16 to –0·58 (0·31; –1·19 to

improvement to 0·65); 0·876 0·10); 0·097 0·03); 0·064

Week 0 ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ··

Week 24 2·95 (1·21), 22 2·78 (1·23), 22 2·14 (0·91), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 2·45 (1·06), 22 2·50 (1·00), 20 2·25 (1·12), 20 ·· ·· ··

Data are mean (SD), number of observations, unless otherwise specified. The effects are common to all follow-up times and are analysed by intention to treat. CBT=cognitive

behavioural therapy. QPR=Questionnaire about Process of Recovery. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PSP=Personal and Social Performance Scale. CGI=Clinical Global

Impressions of Symptom Severity and Improvement Scale.

Table 4: Secondary outcomes

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8 7

Articles

(p=0·003) groups (table 6). The difference in adverse

Deterioration Improvement

effects between the combined group and the

>25% >50% >25% >50% antipsychotics group was not significant (table 6). In the

Intention-to-treat analysis as-treated analysis, no hospital admissions were recorded

24 weeks among those in the antipsychotics group or those who

CBT 0 2 8 2 received no interventions (appendix). Two participants in

Antipsychotics 0 1 5 3 the CBT group (four admissions) and four people in the

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 0 11 7 combined group were admitted to hospital (appendix).

52 weeks Only three deteriorations were noted at 6 or 12 weeks in

CBT 0 1 8 4 monotherapy participants (two in the antipsychotics

Antipsychotics 2 0 8 5 group and one in the CBT group).

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 0 7 6 We recorded another ten potential serious adverse

As-treated analysis events in nine participants (appendix). Only one of these

24 weeks events was thought to be related to the trial (the overdose

CBT 0 1 8 3 of three paracetamol tablets in a participant in the CBT

Antipsychotics 0 1 3 2 group). Only three participants (two in the antipsychotics

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 1 9 4 group, one in the CBT group) met our deterioration

Neither 0 0 4 3

criteria at 6 or 12 weeks, which prompted an offer to move

52 weeks

into the combined arm.

CBT 0 0 6 6

Antipsychotics 2 0 6 0

Discussion

Our single-blind, randomised, controlled pragmatic

Antipsychotics plus CBT 0 1 8 4

pilot and feasibility trial showed that a study comparing

Neither 0 0 3 5

antipsychotics, CBT, and antipsychotics plus CBT is

Data are n. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. possible in people with psychosis. Our trial had low

attrition (<20% at each timepoint) that was balanced

Table 5: Participants with improvements or deteriorations in total

scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale at 24 and 52 weeks across interventions, and only a small proportion of

participants received an intervention to which they were

not allocated. All three interventions were broadly safe

100% indicates they had taken every dose over the past and acceptable.

month). The mean baseline PANSS total score in the overall

The proportion of patients receiving allocated population was 70·4, which is similar to the baseline

interventions was similar across groups (table 2). PANSS score of 73·8 seen in the CAFÉ study,29 but lower

15 patients (58%) in the CBT group, 15 (63%) in the than the baseline score of 88·5 in EUFEST30 (CAFÉ and

antipsychotics group, and 14 (56%) in the combined EUFEST are large, 1-year randomised controlled trials of

group received the correct allocated intervention. antipsychotics in early psychosis). The mean changes in

Psychiatric symptoms were significantly reduced over PANSS total scores we noted from baseline to 52 weeks

time across all conditions (appendix). The PANSS total (antipsychotics 13·3, CBT 12·3, antipsychotics plus

score differed significantly between the combined group CBT 13·4) were all within the range of those noted with

and the CBT group (p=0·019), but not between the the three antipsychotics in CAFÉ (olanzapine 18·4,

combined group and the antipsychotics group quetiapine 15·6, risperidone 8·4), but lower than those

(p=0·064), or between the CBT group and the in EUFEST (changes of around 35 points with the five

antipsychotics group (p=0·637; table 3). Table 4 shows antipsychotics assessed). The mean PANSS reductions

results for secondary outcomes. PANSS analyses that we noted were less than the 15 points estimated to be

did not include age as a covariate had similar results to equivalent to a rating of minimal improvement on the

the primary analyses (appendix). Clinical Global Impressions scale,31 although the

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the numbers of threshold for minimal improvement could be lower for

participants in each group (completer-only data— patients with less severe symptoms at baseline.31 The

ie, observed cases) achieving 25% and 50% improvements reductions in our trial were larger than the minimal

on adjusted PANSS total scores28 were highest in the clinically important difference in PANSS total score

combined arm at 6 months, and very similar across all estimated to be associated with obtaining employment as

groups at 12 months (table 5). In the as-treated analysis, an objective measure of functioning (8·3 points),32 and

few deteriorations were noted in any groups at both similar to the minimal clinically important difference

6 months and 12 months (table 5). associated with patient-rated improvement (11·2 points).33

Adverse effects (as measured by ANNSERS) were We recorded improvement across measures of symptoms

significantly less common in the CBT group than in the and personal and social recovery, functioning, and quality

antipsychotics (p=0·017) or the antipsychotics plus CBT of life, irrespective of intervention.

8 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8

Articles

Antipsychotics CBT (n=20) Antipsychotics plus Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

(n=21) CBT (n=21)

CBT vs antipsychotics CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT Antipsychotics vs

antipsychotics plus CBT

ANNSERS

Number of side-effects ·· ·· ·· 3·22 (1·35; 0·58 to 5·87); 3·99 (1·35; 1·36 to 6·64); 0·78 (1·37; –1·91 to 3·47);

0·017 0·003 0·572

Week 0 8·52 (3·66), 21 8·55 (3·94), 20 10·33 (4·54), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 8·47 (5·62), 17 5·7 (3·23), 20 10·05 (5·35), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 9·06 (5·5), 16 4·74 (3·35), 19 10·42 (5·90), 19 ·· ·· ··

Total score ·· ·· ·· 5·12 (2·05; 1·11 to 9·14); 6·30 (2·03; 2·32 to 10·27); 1·17 (2·07; –2·89 to 5·24);

0·012 0·002 0·571

Week 0 11·57 (5·48), 21 11·7 (6·21), 20 13·62 (6·18), 21 ·· ·· ··

Week 24 11·59 (8·40), 17 7·45 (4·99), 20 14·16 (8·42), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 12·94 (8·77), 16 6·21 (5·07), 19 13·79 (7·63), 19 ·· ·· ··

Cholesterol

HDL (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· 0·07 (0·09; –0·10 to 0·24); 0·09 (0·09; –0·09 to 0·26); 0·01 (0·08; –0·15 to 0·17);

0·389 0·346 0·893

Week 0 1·37 (0·35), 16 1·21 (0·32), 12 1·37 (0·41), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 1·37 (0·38), 14 1·21 (0·29), 9 1·54 (0·49), 15 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 1·15 (0·36), 8 1·36 (0·31), 6 1·24 (0·21), 7 ·· ·· ··

Total/HDL ratio ·· ·· ·· –0·08 (0·22; –0·50 to 0·35); 0·01 (0·24; –0·45 to 0·48); 0·09 (0·21; –0·33 to 0·51);

0·722 0·950 0·667

Week 0 3·4 (0·85), 16 3·58 (0·66), 12 3·06 (0·81), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 3·63 (1·25), 14 3·64 (0·44), 10 3·23 (0·65), 14 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 4·41 (2·11), 8 3·51 (0·53), 7 3·68 (1·05), 6 ·· ·· ··

LDL (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· –0·21 (0·28; –0·76 to 0·33); –0·15 (0·29; –0·72 to 0·42); 0·06 (0·26; –0·45 to 0·58);

0·449 0·615 0·809

Week 0 2·42 (0·79), 14 2·44 (0·58), 10 2·34 (0·72), 11 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 2·59 (0·72), 12 2·79 (0·92), 8 2·63 (0·74), 12 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 3·02 (0·84), 6 2·83 (0·59), 6 2·63 (0·90), 6 ·· ·· ··

Triglycerides (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· 0·08 (0·19; –0·29 to 0·45); –0·27 (0·20; –0·66 to 0·12); –0·35 (0·18; –0·71 to 0·00);

0·659 0·170 0·051

Week 0 1·23 (0·45), 14 1·16 (0·56), 10 1·15 (0·58), 11 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 1·45 (0·75), 12 1·4 (0·63), 8 1·11 (0·63), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 1·62 (1·11), 6 0·97 (0·28), 6 2·57 (4·08), 7 ·· ·· ··

Prolactin (mU/L) ·· ·· ·· 23·12 (26·73; –29·27 to –7·39 (29·00; –64·22 to –30·51 (28·28; –85·94 to

75·50); 0·387 49·44); 0·799 24·93); 0·281

Week 0 162·86 (98·96), 14 188·42 (72·73), 12 221·58 (74·14), 12 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 206·92 (83·76), 13 196·22 (83·08), 9 180 (73·90), 10 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 136·71 (53·84), 7 201·83 (93·32), 6 186·13 (88·69), 8 ·· ·· ··

Glucose (mmol/L) ·· ·· ·· –0·56 (0·50; –1·53 to 0·42); –0·75 (0·52; –1·77 to 0·27); –0·19 (0·45; –1·07 to 0·68);

0·265 0·148 0·662

Week 0 6·6 (7·63), 15 5·04 (2·68), 12 4·72 (0·95), 13 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 4·76 (1·10), 11 5·2 (1·72), 7 4·55 (0·55), 14 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 4·63 (0·65), 8 5·32 (1·81), 6 4·11 (0·76), 7 ·· ·· ··

Weight (kg) ·· ·· ·· 1·80 (1·40; –0·94 to 4·54); 3·70 (1·41; 0·93 to 6·47); 1·90 (1·36; –0·76 to 4·57);

0·198 0·009 0·162

0 75·91 (20·31), 21 73·62 (15·72), 18 70·93 (12·97), 21 ·· ·· ··

6 77·06 (18·20), 16 74·84 (17·27), 15 70·82 (13·56), 18 ·· ·· ··

12 72·87 (13·32), 16 73·58 (15·66), 19 73·86 (14·01), 19 ·· ·· ··

24 78·21 (17·38), 18 72·12 (15·14), 20 75·33 (13·59), 16 ·· ·· ··

52 74·87 (15·34), 16 75·71 (14·88), 15 75·22 (15·07), 18 ·· ·· ··

(Table 6 continues on next page)

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8 9

Articles

Antipsychotics CBT (n=20) Antipsychotics plus Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value

(n=21) CBT (n=21)

CBT vs antipsychotics CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT Antipsychotics vs

antipsychotics plus CBT

(Continued from previous page)

Systolic blood pressure ·· ·· ·· 1·36 (2·76; –4·06 to 6·78); 0·52 (2·83; –5·04 to 6·07); –0·84 (2·44; –5·61 to 3·93);

(mm Hg) 0·624 0·855 0·730

Week 0 124·12 (12·91), 20 124·05 (15·02), 14 118·98 (11·11), 19 ·· ·· ··

Week 12 124·49 (16·53), 14 122·13 (10·16), 14 123·86 (14·13), 17 ·· ·· ··

Week 52 123·6 (13·28), 16 122·22 (10·67), 10 116·9 (8·47), 18 ·· ·· ··

Data are mean (SD), number of observations on an as-treated basis, unless otherwise specified. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. ANNSERS=Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale.

*ANNSERS consists of 43 non-neurological side-effects, each rated as absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3), with a total possible score of 129.

Table 6: Secondary outcomes (adverse effects)

Antipsychotics plus CBT was significantly more weekly contact with trial staff tasked with reporting

efficacious than CBT alone (p=0·019), but the difference adverse effects (the trial therapists). By contrast, patients

between antipsychotics plus CBT and antipsychotics in the antipsychotics group had much less frequent

alone was not significant (p=0·06). However, because contact with trial staff (the trial research assistants).

this study was a pilot and feasibility trial, it was not The number of sessions attended and compliance with

powered to reliably detect differences between groups, homework tasks suggests that CBT was delivered

and any significant differences should be treated with successfully to most participants, although competence of

caution. Efficacy did not differ significantly between the CBT delivery and adherence to the treatment protocol was

CBT group and the antipsychotic group, which is not monitored systematically. Antipsychotics were

noteworthy given that CBT finished after 24 weeks selected on an individual basis, consistent with National

whereas antipsychotic treatment could last 52 weeks Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance. The

(median duration 44·5 weeks). The absence of any four antipsychotics used most frequently in the study

apparent differences between the three groups at 6 weeks (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) are

is also noteworthy (appendix), because 6 weeks is a the four antipsychotics most commonly initiated in

common length for drug trials. The number of routine clinical practice in first-episode services in

participants with PANSS-rated deterioration was low the UK.34 Dose and duration of antipsychotic treatment

across all groups at each timepoint, with no suggestion were at the discretion of the treating clinician and patient

that CBT was worse than antipsychotics or combination wishes. One patient’s primary antipsychotic was pro

treatment. Only three early deteriorations (ie, at 6 or mazine, which is approved to treat agitation but not

12 weeks) were noted, two in the antipsychotics group psychosis; the low dose given was insufficient to be

and one in the CBT group. regarded as an effective antipsychotic dose (appendix).

Fewer side-effects were noted in the CBT group than in The mean modal doses of the other primary antipsychotics

the antipsychotic group or the combined intervention prescribed were at the low end of the dose ranges

group. However, this difference is more accounted for by recommended to treat psychosis, which is probably

reduction in side-effects over time in the CBT group than because participants were recruited almost exclusively

by increases in side-effects in the antipsychotic and from early-intervention services. People with first-episode

combined groups. This decrease in side-effects in the psychosis respond to doses of antipsychotics lower than

CBT group could be related to many ANNSERS items those required for multi-episode schizophrenia,29 and are

being non-specific (eg, sleep problems, memory and more sensitive to side-effects than patients with multi-

attention, loss of libido, loss of energy, and autonomic episode schizophrenia, which has led to guidelines recom

symptoms). Such symptoms could be symptoms of a mending low doses.35,36 Nevertheless, the doses of some of

psychotic disorder or a comorbid illness, or could be the antipsychotics, especially quetiapine, were lower than

antipsychotic side-effects. Some patients in the CBT the corresponding doses used in the CAFÉ and EUFEST

group and the combined group were admitted to hospital, trials in first-episode psychosis. In most cases in our

whereas no patients in the antipsychotic group were. study, when duration of antipsychotic treatment was

Similarly, no serious adverse events were reported to the known, the primary antipsychotic was continued for

ethics committee for the antipsychotics group, compared 6 weeks or longer, suggesting that treatment duration was

with two for the CBT group and four for the combined sufficient to establish effectiveness. 12 (32%) of the

group (although only one was deemed treatment related). 38 participants who started antipsychotic treatment

There is increased opportunity for adverse events to be switched anti psychotic at least once, implying pers

observed in the patients receiving CBT, because they had everance to identify an effective medication. Overall, use

10 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8

Articles

of antipsychotics was pragmatic and broadly consistent The design of our study (ie, three active intervention

with clinical practice in early-intervention services and arms), combined with the fact that most participants

treatment guidelines. received care from early-intervention services, means that

The study had several limitations. The pilot and we cannot rule out the possibility that recorded benefits

feasibility trial design and small sample size mean that could be attributable to generic factors such as good care

caution should be used when interpreting the statistical coordination, engagement, assertive outreach, and crisis

tests and significance values. Although only 12% of management, rather than the specific active treatments.

participants received an intervention they were not Failure to include the EQ5D means we could not examine

allocated to, a reasonable proportion did not take up the quality-adjusted life-years and cost-effectiveness.

offer of allocated interventions, reflecting that in clinical The main implication of this trial is that an adequately

practice many people do not comply with medication powered efficacy and effectiveness trial is needed to

regimens,34 and some do not engage with talking therapies. provide evidence about relative efficacy of antipsychotics

Such rates of non-adherence are common in drug and and CBT. In our trial, participants were almost exclusively

psychological therapy trials. Operationalisation of experiencing a first episode of psychosis, so a definitive

antipsychotic treatment in terms of target doses, minimal trial should target this population and recruit via early-

duration of trials, and encouraging switching if treatment intervention services (appendix). A trial in people with

was unsatisfactory might have improved the efficacy of multiple episode psychotic disorders would probably not

drug treatment, but higher doses might have led to more be feasible in generic community mental health teams,

side-effects and greater dropout rates. In our trial, mostly because potential participants are already

medication was prescribed and dispensed in accordance prescribed antipsychotics. At present, it seems reasonable

with normal clinical practice, as opposed to delivery of to support people with psychosis (who do not present

medication to patients and use of regular pill counts, both immediate risk to themselves or others) to make informed

of which might improve adherence. The absence of weight choices as outlined in the National Institute for Health

gain in the antipsychotics group casts doubt on adherence. and Care Excellence guidelines,1 which recommend

We did not have a standardised operating procedure for advising people who want to try psychological

weight measurement that emphasised consistency of interventions alone that such inter ventions are more

flooring, and many assessments were done in participants’ effective when delivered in conjunction with antipsychotic

homes. Therefore, weight data could contain errors. medication, but allowing them to try family intervention

Another limitation is that we did not systematically record and CBT without antipsychotics while agreeing a time to

use of other medications such as antidepressants or review treatment options, including introduction of anti

anxiolytics, or measure substance and alcohol use. psychotics.

Response rates on the PANSS and the degree of Contributors

improvement on the Clinical Global Impressions scale All authors were involved in study design, management, and delivery,

were lower in our trial than in previous 52-week and contributed to drafting of this Article. APM was the chief

investigator, conceived the study, prepared the protocol, supervised

randomised controlled trials of antipsychotics in first- researchers, had overall responsibility for day-to-day running of the study,

episode psychosis.29,30 However, data analytic strategies and interpreted data, led writing of the Article, and is the study guarantor.

high attrition in these studies might have increased the APM, PF, EKM, NH, AS, SEB, and JP-C prepared the treatment protocol

risk of bias, which could inflate effects. In EUFEST,30 for and trained and supervised the therapists. APM, HL, MP, and PMH

trained the researchers in use of psychiatric interviews, and supervised

example, data obtained before treatment discontinuation and monitored standards of psychiatric interviewing and assessment

were used in analysis of PANSS outcomes, which was throughout the trial. APM, PF, ARY, and PMH advised on diagnostic

likely to have introduced bias given the high frequency of ratings and inclusion and exclusion criteria. DS, ARY, and PMH advised

discontinuation (33–72%, depending on the specific drug). on medical and pharmacological issues and liaised with prescribers.

HL was the trial manager, supervised and coordinated recruitment,

CAFÉ had very high attrition at 52 weeks (67–73%, contributed to training of research staff, and was responsible for staff

depending on drug), which probably introduced bias.29 management and overall study coordination. HL, LC, RS, and MP were

Response is also dependent on patient and illness responsible for maintaining reliability of assessment procedures and data

characteristics, which vary between studies. Our study collection. RE, the trial statistician, advised on randomisation and all

statistical aspects of the trial, developed the analysis plan, and did the

mostly involved participants who met PANSS-defined statistical analyses. LD was the health economist. RB was a service user

criteria for acceptance into early-intervention services, consultant involved in all aspects of the study.

whereas EUFEST and CAFÉ only included participants Declaration of interests

with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses. APM, PF, and SEB deliver training workshops and have written textbooks

Our sample was diagnostically heterogeneous: about CBT for psychosis, for which they receive fees. All authors have

done funded research on CBT for psychosis, and RE, ARY, LD, and PMH

73 participants were recruited from early-intervention

have done funded research on antipsychotics. APM, PF, EKM, NH, AS,

services, which operationally define first-episode psych SEB, JP-C, and VB deliver CBT in the National Health Service. DS is an

osis with the PANSS. Therefore, our findings are expert adviser for the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence

generalisable to early-intervention services only, at least Centre for Guidelines and a board member of the National Collaborating

Centre of Mental Health. ARY has received honoraria from Janssen Cilag

in the UK, and should not be generalised to patients

and Sunovion. PMH has received honoraria for lecturing or consultancy

with long-term schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8 11

Articles

work from Allergan, Galen, Janssen, Lundbeck, NewBridge 15 Morrison AP. The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis:

Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Teva, plus conference support an integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions.

from Janssen, Lundbeck and Sunovion. All other authors declare no Behav Cogn Psychother 2001; 29: 257–76.

competing interests. 16 Morrison AP. A manualised treatment protocol to guide delivery

of evidence-based cognitive therapy for people with distressing

Acknowledgments psychosis: learning from clinical trials. Psychosis 2017; 9: 271–81.

This trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research 17 Blackburn IM, James I, Milne D, Baker CA, Standart S, Garland A.

(NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme The revised cognitive therapy scale (CTS-R): psychometric properties.

(Grant Reference Number PB-PG- 1112-29057). The views expressed are Behav Cogn Psychother 2001; 29: 431–46.

those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health 18 Kay S, Fiszbein A, Opler L. The positive and negative syndrome

Service, NIHR, the Department of Health, the National Institute for scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13: 261–76.

Health and Care Excellence, or the National Collaborating Centre for 19 Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Mental Health. We thank the Psychosis Research Unit Service User Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983; 67: 361–70.

Reference Group for their contributions to study design and 20 WHO Quality of Life Group. The World Health Organization

development of study-related materials, the Greater Manchester Clinical quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general

Research Network for their support and assistance, and David Kingdon psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998; 46: 1569–85.

and John Norrie, the independent members of our trial steering and data 21 Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R.

monitoring committee. We also thank Elizabeth Pitt for acting as a Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the

service user consultant for the trial (because of unforeseen DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale

circumstances, she could not be contacted about this acknowledgment). (SOFAS) to assess routine social funtioning.

Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2000; 101: 323–29.

References 22 Law H, Neil ST, Dunn G, Morrison AP. Psychometric properties of

1 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR).

schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. London: Schizophr Res 2014; 156: 184–89.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014.

23 Guy W. Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville:

2 Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws KR. US Department of Heath, Education, and Welfare Public Health

Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1976.

systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential

24 Ohlsen R, Williamson R, Yusufi B, et al. Interrater reliability of the

bias. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204: 20–29.

Antipsychotic Non-Neurological Side-Effects Rating Scale measured

3 Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for in patients treated with clozapine. J Psychopharmacol 2008; 22: 323–29.

schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor.

25 Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size

Schizophr Bull 2008; 34: 523–37.

determination. Stat Med 1995; 14: 1933–40.

4 Mehl S, Werner D, Lincoln TM. Does cognitive behavior therapy for

26 Law H, Carter L, Sellers R, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial

psychosis (CBTp) show a sustainable effect on delusions?

comparing antipsychotic medication, to cognitive behavioural

A meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2015; 6: 1450.

therapy to a combination of both in people with psychosis:

5 Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and rationale, study design and baseline data of the COMPARE trial.

tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Psychosis 2017; 9: 193–204.

a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 382: 951–62.

27 Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data.

6 Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM. How effective London: John Wiley and Sons, 2002.

are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of

28 Leucht S, Kissling W, Davis JM. The PANSS should be rescaled.

placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 14: 429–47.

Schizophr Bull 2010; 36: 461–62.

7 Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled

29 McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability

antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review,

of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early

Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors.

psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison.

Am J Psychiatry 2017; 174: 927–42.

Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1050–60.

8 Zhu Y, Li C, Huhn M, Rothe P, et al. How well do patients with a first

30 Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. Effectiveness of

episode of schizophrenia respond to antipsychotics: a systematic

antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and

review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology 2017;

schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial.

27: 835–44.

Lancet 2008; 371: 1085–97.

9 Haddad P, Sharma S. Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics:

31 Leucht S, Kane JM, Etschel E, Kissling W, Hamann J, Engel RR.

differential risk and clinical implications. CNS Drugs 2007;

Linking the PANSS, BPRS, and CGI: clinical implications.

21: 911–36.

Neuropsychopharmacol 2006; 31: 2318–25.

10 Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, et al. Prevalence, incidence and

32 Thwin SS, Hermes E, Lew R, et al. Assessment of the minimum

mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and

clinically important difference in quality of life in schizophrenia

specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of

measured by the Quality of Well-Being Scale and disease-specific

3 211 768 patients and 113 383 368 controls. World Psychiatry 2017;

measures. Psychiatry Res 2013; 209: 291–96.

16: 163–80.

33 Hermes EDA, Sokoloff DM, Stroup TS, Rosenheck RA.

11 Taylor M, Perera U. NICE CG178 psychosis and schizophrenia in

Minimum clinically important difference in the Positive And Negative

adults: treatment and management—an evidence-based guideline?

Syndrome Scale using data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial.

Br J Psychiatry 2015; 206: 357–59.

J Clin Psychiatry 2012; 73: 526–32.

12 Morrison AP, Birchwood M, Pyle M, et al. Impact of cognitive

34 Whale R, Harris M, Kavanagh G, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotics

therapy on internalised stigma in people with at-risk mental states.

used in first-episode psychosis: a naturalistic cohort study.

Br J Psychiatry 2013; 203: 140–45.

BJPsych Open 2016; 2: 323–29.

13 Morrison AP, Turkington D, Pyle M, et al. Cognitive therapy for

35 Barnes TR. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological

people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders not taking

treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British

antipsychotic drugs: a single-blind randomised controlled trial.

Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2011;

Lancet 2014; 383: 1395–403.

25: 567–620.

14 Goldsmith LP, Lewis SW, Dunn G, Bentall RP. Psychological

36 Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F,

treatments for early psychosis can be beneficial or harmful,

Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic

depending on the therapeutic alliance: an instrumental variable

dosing. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167: 686–93.

analysis. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 2365–73.

12 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 28, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30096-8

You might also like

- Your Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022From EverandYour Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022No ratings yet

- PIIS2215036618300968Document13 pagesPIIS2215036618300968zuhrul_baladNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673613622461 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0140673613622461 MainFrancisco Javier RamosNo ratings yet

- Clinical Effectiveness and Acceptability of StructDocument10 pagesClinical Effectiveness and Acceptability of StructArthur AlvesNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Clozapine-Resistant Schizophrenia (FOCUS) : An Assessor-Blinded, Randomised Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesCognitive Behavioural Therapy in Clozapine-Resistant Schizophrenia (FOCUS) : An Assessor-Blinded, Randomised Controlled TrialRabiatul AdawiyahNo ratings yet

- Background: Lancet Psychiatry 2017Document11 pagesBackground: Lancet Psychiatry 2017Manya DhuparNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2215036616303789Document11 pagesPi Is 2215036616303789U of T MedicineNo ratings yet

- Goldstein 2010Document10 pagesGoldstein 2010esckere papas fritasNo ratings yet

- Sustained Benefit of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Health Anxiety in Medical Patients (CHAMP) Over 8 Years A Randomised-Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesSustained Benefit of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Health Anxiety in Medical Patients (CHAMP) Over 8 Years A Randomised-Controlled TrialJan LAWNo ratings yet

- Paroxetine, Cognitive Therapy or Their Combination in The Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder With and Without Avoidant Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument11 pagesParoxetine, Cognitive Therapy or Their Combination in The Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder With and Without Avoidant Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical TrialAdm Foto MahniteseNo ratings yet

- RCT - Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - 2017Document10 pagesRCT - Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - 2017RayssaNo ratings yet

- Špela PDFDocument11 pagesŠpela PDFŠpela MiroševičNo ratings yet

- 2022 de VriesDocument8 pages2022 de Vriesmvillar15_247536468No ratings yet

- Comparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderDocument8 pagesComparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderAnanda Amanda cintaNo ratings yet

- Jiwa 1Document9 pagesJiwa 1Hamidah S.No ratings yet

- Rector Et Al-2019-British Journal of Clinical PsychologyDocument18 pagesRector Et Al-2019-British Journal of Clinical PsychologyJulia DGNo ratings yet

- Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Psychosis (Cacbtp) in PakistanDocument8 pagesPilot Randomised Controlled Trial of Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Psychosis (Cacbtp) in Pakistanzuhrul_baladNo ratings yet

- Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of 32 Oral Antipsychotics For The Acute Treatment of Adults With Multi-Episode Schizophrenia PDFDocument13 pagesComparative Efficacy and Tolerability of 32 Oral Antipsychotics For The Acute Treatment of Adults With Multi-Episode Schizophrenia PDFfrancesca_valdiviaNo ratings yet

- Anti Dep and Alzheimers Lancet 2011Document9 pagesAnti Dep and Alzheimers Lancet 2011bcy123No ratings yet

- Gloster Et Al., (2019)Document15 pagesGloster Et Al., (2019)Jonathan PitreNo ratings yet

- Physical Exercise and iCBT in Treatment of DepressionDocument9 pagesPhysical Exercise and iCBT in Treatment of DepressionCarregan AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Artikel InternasionalDocument15 pagesArtikel InternasionalFitriatul MunawarohNo ratings yet

- Depression TreatmentDocument8 pagesDepression TreatmentAkshay HegdeNo ratings yet

- We Therell 2009Document10 pagesWe Therell 2009Oslo SaputraNo ratings yet

- On Predicting Improvement and Relapse in Generalized Anxiety Disorder Following PsychotherapyDocument19 pagesOn Predicting Improvement and Relapse in Generalized Anxiety Disorder Following PsychotherapyElizaIancuNo ratings yet

- Internet-Versus Group-Administered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Panic Disorder in A Psychiatric Setting: A Randomised TrialDocument10 pagesInternet-Versus Group-Administered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Panic Disorder in A Psychiatric Setting: A Randomised TrialSophi RetnaningsihNo ratings yet

- Cuijpers Et Al., (2021)Document11 pagesCuijpers Et Al., (2021)Jonathan PitreNo ratings yet

- Birchwood 2014Document11 pagesBirchwood 2014Lisa MaghfirahNo ratings yet

- Eca MBCT en TocDocument11 pagesEca MBCT en TocMiriam JaraNo ratings yet

- Artículo Grupo 3Document11 pagesArtículo Grupo 3pepeluchovelezquezadaNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument11 pagesArticles: BackgroundNurul AhdiahNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Scoping Review of Psychological Therapies For Psychosis Within Acute Psychiatric In-Patient Settings.Document8 pagesA Systematic Scoping Review of Psychological Therapies For Psychosis Within Acute Psychiatric In-Patient Settings.Eric KatškovskiNo ratings yet

- The Role of CBT in Relapse Prevention of SchizophreniaDocument2 pagesThe Role of CBT in Relapse Prevention of SchizophreniaKorn IbraNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Acute Stress DisorderDocument11 pagesTreatment of Acute Stress DisorderKusnanto Penasehat Kpb RyusakiNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Videoconference-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adults With Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic and Meta-Analytic ReviewDocument16 pagesEffectiveness of Videoconference-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adults With Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic and Meta-Analytic ReviewlaiaNo ratings yet

- Edited By: Dr. Javaid Akhtar, MCPS, FCPS, Head Of: Search StrategyDocument3 pagesEdited By: Dr. Javaid Akhtar, MCPS, FCPS, Head Of: Search StrategyKaram Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- (Stanley) Joc90025 - 1460 - 1467Document8 pages(Stanley) Joc90025 - 1460 - 1467niia kurniiasihNo ratings yet

- Bryant20et20al20 20additive20benefit20of20hypnosis20and20cbtDocument8 pagesBryant20et20al20 20additive20benefit20of20hypnosis20and20cbtita elizabethNo ratings yet

- Meta-Analysis of The Efficacy of Treatments For PTSDDocument10 pagesMeta-Analysis of The Efficacy of Treatments For PTSDJulianaNo ratings yet

- Metanalisis Comparacion de La Eficacia de de La Psicoterapia en Pacientes DeprimidosDocument17 pagesMetanalisis Comparacion de La Eficacia de de La Psicoterapia en Pacientes DeprimidosDulce HerreraNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Cognitive Therapy in Depressed PatientsDocument14 pagesA Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Cognitive Therapy in Depressed PatientsDragan DjundaNo ratings yet

- Evid Based Mental Health 2001 Therapeutics 82Document2 pagesEvid Based Mental Health 2001 Therapeutics 82Fernanda Avila CastroNo ratings yet

- 2014 TMO en Dolores de Cabeza, Revisión SistemáticaDocument8 pages2014 TMO en Dolores de Cabeza, Revisión Sistemáticaignacio quirogaNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Breedvelt 2021 Oi 210022 1628043342.75801Document8 pagesJamapsychiatry Breedvelt 2021 Oi 210022 1628043342.75801Jonathan PitreNo ratings yet

- PIIS2215036623002584Document12 pagesPIIS2215036623002584Dr. Nivas SaminathanNo ratings yet

- Managing Antidepressant Discontinuation A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesManaging Antidepressant Discontinuation A Systematic ReviewAlejandro Arquillos ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- May 09 Journals (Mostly) : 63 AbstractsDocument14 pagesMay 09 Journals (Mostly) : 63 AbstractssunkissedchiffonNo ratings yet

- Depresia CazDocument19 pagesDepresia CazBetu SasuNo ratings yet

- BrueraDocument21 pagesBrueraThatiana GimenesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal JiwaDocument6 pagesJurnal JiwaoldDEUSNo ratings yet

- Artigo InglesDocument11 pagesArtigo InglesEllen AndradeNo ratings yet

- Artículo Terapia EsquemasDocument24 pagesArtículo Terapia EsquemasAna Salvador CastellanoNo ratings yet

- Metaanalisis Psicoterapia Resultados PPLDocument20 pagesMetaanalisis Psicoterapia Resultados PPLXavierBilbaoNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Papola 2023 Oi 230080 1697118575.84256Document11 pagesJamapsychiatry Papola 2023 Oi 230080 1697118575.84256Renan CruzNo ratings yet

- Patients SchizofreniaDocument3 pagesPatients SchizofreniaArinaDogaruNo ratings yet

- And Behavioural Stress Management For Severe Health Anxiety: Internet-Delivered Exposure-Based Cognitive-Behavioural TherapyDocument9 pagesAnd Behavioural Stress Management For Severe Health Anxiety: Internet-Delivered Exposure-Based Cognitive-Behavioural TherapyRoxana MălinNo ratings yet

- A Study of Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patients PDFDocument34 pagesA Study of Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patients PDFIrdha Nasta KurniaNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Stroup 2019 Oi 180113Document8 pagesJamapsychiatry Stroup 2019 Oi 180113opanocayNo ratings yet

- Efficacy For Treatment Anxiety DisordersDocument10 pagesEfficacy For Treatment Anxiety DisordersAnderson GaldinoNo ratings yet

- Depression and Anxiety - 2022 - Gutner - A Pilot Randomized Effectiveness Trial of The Unified Protocol in Trauma ExposedDocument11 pagesDepression and Anxiety - 2022 - Gutner - A Pilot Randomized Effectiveness Trial of The Unified Protocol in Trauma ExposedCristina Alarcón RuedaNo ratings yet

- Sexual and Physical Abuse and Depressive Symptoms in The UK BiobankDocument10 pagesSexual and Physical Abuse and Depressive Symptoms in The UK BiobankDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Experimental Methods Induce Basic EmotionDocument11 pagesExperimental Methods Induce Basic EmotionDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Yoa70030 1115 1122Document8 pagesYoa70030 1115 1122Dewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Genetic Developmental DisabilityDocument5 pagesGenetic Developmental DisabilityDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet