Professional Documents

Culture Documents

People Vs de Gracia

Uploaded by

Patatas SayoteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

People Vs de Gracia

Uploaded by

Patatas SayoteCopyright:

Available Formats

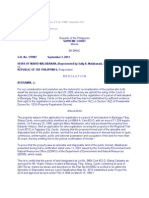

People vs.

De Gracia (1994)

Contention of the State

Accused-appellant Rolando de Gracia was charged in two separate informations for illegal possession of

ammunition and explosives in furtherance of rebellion, and for attempted homicide which were tried

jointly. Appellant was convicted for illegal possession of firearms in furtherance of rebellion, but was

acquitted of attempted homicide.

Defense of the Accused

Appellant principally contends that he cannot be held guilty of illegal possession of firearms for the

reason that he did not have either physical or constructive possession thereof considering that he had

no intent to possess the same; he is neither the owner nor a tenant of the building where the

ammunition and explosives were found; he was merely employed by Col. Matillano as an errand boy; he

was guarding the explosives for and in behalf of Col. Matillano; and he did not have actual possession of

the explosives. He claims that intent to possess, which is necessary before one can be convicted under

Presidential Decree No. 1866, was not present in the case at bar.

Ruling of the Supreme Court

The rule is that ownership is not an essential element of illegal possession of firearms and ammunition.

What the law requires is merely possession which includes not only actual physical possession but also

constructive possession or the subjection of the thing to one's control and management. This has to be

so if the manifest intent of the law is to be effective. The same evils, the same perils to public security,

which the law penalizes exist whether the unlicensed holder of a prohibited weapon be its owner or a

borrower. To accomplish the object of this law the proprietary concept of the possession can have no

bearing whatsoever.

The mere fact of physical or constructive possession is sufficient to convict a person for unlawful

possession of firearms since the offense of illegal possession of firearms is a malum prohibitum punished

by a special law, in which case good faith and absence of criminal intent are not valid defenses.

When the crime is punished by a special law, as a rule, intent to commit the crime is not necessary. It is

sufficient that the offender has the intent to perpetrate the act prohibited by the special law. Intent to

commit the crime and intent to perpetrate the act must be distinguished. A person may not have

consciously intended to commit a crime; but he did intend to commit an act, and that act is, by the very

nature of things, the crime itself. In the first (intent to commit the crime), there must be criminal intent;

in the second (intent to perpetrate the act) it is enough that the prohibited act is done freely and

consciously.

You might also like

- AgathaDocument12 pagesAgathaselvaro menomaroNo ratings yet

- Habeas Corpus - So vs. TaclaDocument2 pagesHabeas Corpus - So vs. TaclaAlvin Claridades100% (1)

- Criminal Procedure. MCQDocument2 pagesCriminal Procedure. MCQBencio AizaNo ratings yet

- People V GreyDocument1 pagePeople V GreyAlexis Dominic San ValentinNo ratings yet

- COMELEC vs. SILVADocument1 pageCOMELEC vs. SILVAcsalipio24No ratings yet

- La Chemise Lacoste vs. Fernandez: Foreign Corp's Right to SueDocument2 pagesLa Chemise Lacoste vs. Fernandez: Foreign Corp's Right to SueMark Dungo67% (3)

- As Filed ComplaintDocument33 pagesAs Filed ComplaintTrevor BallantyneNo ratings yet

- UFC Philippines V Barrio FiestaDocument4 pagesUFC Philippines V Barrio FiestaMaria Therese100% (5)

- Anti Violence Against Women and Their Children RA 9262Document64 pagesAnti Violence Against Women and Their Children RA 9262Patatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- PDF 6 Case Republic Planters Bank Vs Agana Corporation LawDocument2 pagesPDF 6 Case Republic Planters Bank Vs Agana Corporation LawPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Prosecution Must Prove All Elements of Crime ChargedDocument6 pagesProsecution Must Prove All Elements of Crime ChargedMariaAyraCelinaBatacanNo ratings yet

- Gamboa v. CADocument4 pagesGamboa v. CANeil Subac100% (1)

- IPAP V OchoaDocument4 pagesIPAP V OchoaPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Local Initiative and ReferendumDocument14 pagesLocal Initiative and ReferendumPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Agote Vs Lorenzo DigestDocument2 pagesAgote Vs Lorenzo DigestRicky James Laggui Suyu100% (1)

- Austria vs Masaquel Land Dispute Judge BiasDocument1 pageAustria vs Masaquel Land Dispute Judge BiasJoona Kis-ingNo ratings yet

- Cabigas Reynes v. People, 152 SCRA 18Document5 pagesCabigas Reynes v. People, 152 SCRA 18PRINCESS MAGPATOCNo ratings yet

- Foreign AffairsDocument268 pagesForeign AffairsRashid AliNo ratings yet

- Lgu Elective Officials: Vacancies and SuccessionDocument15 pagesLgu Elective Officials: Vacancies and SuccessionPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Cordova V CordovaDocument2 pagesCordova V CordovaPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Sps. Dato v. Bank of The Philippine IslandDocument10 pagesSps. Dato v. Bank of The Philippine IslandSamuel John CahimatNo ratings yet

- Arimas Vs ArimasDocument2 pagesArimas Vs ArimasAnonymous iScW9lNo ratings yet

- Cabigas v. PeopleDocument4 pagesCabigas v. PeopleresjudicataNo ratings yet

- People vs. Tee, 395 SCRA 419, January 20, 2003Document3 pagesPeople vs. Tee, 395 SCRA 419, January 20, 2003Rizchelle Sampang-ManaogNo ratings yet

- Translation Problems and SolutionsDocument8 pagesTranslation Problems and SolutionsPatatas Sayote100% (1)

- People of The PhilipinesDocument4 pagesPeople of The PhilipinesPatrick Marvin BernalNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules in favor of casino patron in chip confiscation caseDocument7 pagesSupreme Court rules in favor of casino patron in chip confiscation caseLuna KimNo ratings yet

- G and M Philippines Inc. Vs Cuambot (507 SCRA 552)Document18 pagesG and M Philippines Inc. Vs Cuambot (507 SCRA 552)Rose MadrigalNo ratings yet

- 1 People V Feloteo - GR No 124212, Jun 5 1998Document2 pages1 People V Feloteo - GR No 124212, Jun 5 1998Aya BeltranNo ratings yet

- Diaz VS PeopleDocument2 pagesDiaz VS PeopleHermay BanarioNo ratings yet

- Rural Bank of Sta. Maria v. CA PDFDocument13 pagesRural Bank of Sta. Maria v. CA PDFSNo ratings yet

- Philippines vs. De Gracia: Illegal Possession of Firearms UphDocument2 pagesPhilippines vs. De Gracia: Illegal Possession of Firearms UphRio TolentinoNo ratings yet

- People vs. RamosDocument6 pagesPeople vs. RamosAndrew Lastrollo100% (1)

- Paas Vs AlmarvezDocument3 pagesPaas Vs AlmarvezEarnswell Pacina Tan100% (2)

- Del Monte Philippines, Inc. v. VelascoDocument3 pagesDel Monte Philippines, Inc. v. VelascoNelly Louie CasabuenaNo ratings yet

- TRANSLATION ERROR CATEGORIESDocument9 pagesTRANSLATION ERROR CATEGORIESPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction - Boto Vs Villena, AC No. 9684, 18 September 2013Document1 pageJurisdiction - Boto Vs Villena, AC No. 9684, 18 September 2013Apple LavarezNo ratings yet

- Persons Sept 6Document20 pagesPersons Sept 6Trisha Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- I No.180 People vs. PerezDocument2 pagesI No.180 People vs. PerezM Grazielle EgeniasNo ratings yet

- Plurality of CrimesDocument5 pagesPlurality of CrimesJoshua Joy CoNo ratings yet

- People Vs PagalanasDocument2 pagesPeople Vs PagalanasLyka Bucalen DalanaoNo ratings yet

- People V. MacaranasDocument2 pagesPeople V. MacaranasChristine Gee100% (1)

- Slu-Lhs v. Dela CruzDocument7 pagesSlu-Lhs v. Dela CruzCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- Del Rosario v Del Rosario (1949) - Wife justified in leaving due to mother-in-law issuesDocument1 pageDel Rosario v Del Rosario (1949) - Wife justified in leaving due to mother-in-law issuesJoanna ENo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Criminal Law: Criminal Liability (Who May Incur?) Classes of FelonyDocument6 pagesCharacteristics of Criminal Law: Criminal Liability (Who May Incur?) Classes of FelonyJohn PatrickNo ratings yet

- AGBAY VsDocument2 pagesAGBAY VsCharlie ThesecondNo ratings yet

- JOURNAL (Tolentino v. Secretary of FinanceDocument1 pageJOURNAL (Tolentino v. Secretary of Financekemberly latabingNo ratings yet

- People vs. GalanoDocument11 pagesPeople vs. GalanoRodesa AbogadoNo ratings yet

- PHILIPPINES v. HERNANDEZDocument2 pagesPHILIPPINES v. HERNANDEZEvangelical Mission College CommunityNo ratings yet

- People V Sope, 1946Document2 pagesPeople V Sope, 1946Leo Mark LongcopNo ratings yet

- People Vs BalatazoDocument7 pagesPeople Vs BalatazoEj AquinoNo ratings yet

- People vs Rodriguez illegal possession firearm absorbed rebellionDocument1 pagePeople vs Rodriguez illegal possession firearm absorbed rebellionDigesting FactsNo ratings yet

- Espino v. PeopleDocument2 pagesEspino v. PeopleIris DinahNo ratings yet

- Ruling on treachery in murder caseDocument1 pageRuling on treachery in murder caseSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- People vs. DinolaDocument5 pagesPeople vs. Dinolanido12100% (1)

- People Vs RealDocument5 pagesPeople Vs RealJonah100% (1)

- Malabanan v. Republic of The Philippines en Banc G.R. No. 179987, 3 September 2013Document11 pagesMalabanan v. Republic of The Philippines en Banc G.R. No. 179987, 3 September 2013herbs22225847No ratings yet

- PEOPLE V. KOTTINGER: PHILIPPINE PICTURES NOT OBSCENEDocument3 pagesPEOPLE V. KOTTINGER: PHILIPPINE PICTURES NOT OBSCENEEthan KurbyNo ratings yet

- Advincula V Advincula.Document4 pagesAdvincula V Advincula.jetski loveNo ratings yet

- Standing to Question Legitimacy in Property Partition CaseDocument9 pagesStanding to Question Legitimacy in Property Partition CaseMaxencio RiosNo ratings yet

- Vino v. People (1989) : Correccional As Minimum To Prision MayorDocument19 pagesVino v. People (1989) : Correccional As Minimum To Prision MayorMarisseAnne CoquillaNo ratings yet

- People Vs Campos 202 Scra 387Document2 pagesPeople Vs Campos 202 Scra 387Clifford Tubana0% (1)

- P V LobitaniaDocument16 pagesP V LobitaniaJanelle Leano MarianoNo ratings yet

- Umil V Ramos 1Document4 pagesUmil V Ramos 1Chino SisonNo ratings yet

- De Guzman Vs PP DigestDocument2 pagesDe Guzman Vs PP DigestLim JacquelineNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs Abrogar Ruling on TheftDocument4 pagesLaurel vs Abrogar Ruling on Theftwesternwound82No ratings yet

- Silva Vs CabreraDocument11 pagesSilva Vs CabreraRihan NuraNo ratings yet

- Ninoy Aquino Assassination Trial Declared NullDocument3 pagesNinoy Aquino Assassination Trial Declared NullCalebNo ratings yet

- PNB vs. Uy Teng Piao, G.R. No. L-35252, October 21, 1932Document4 pagesPNB vs. Uy Teng Piao, G.R. No. L-35252, October 21, 1932Lou Ann AncaoNo ratings yet

- Enrile vs. Salazar Ruling on Rebellion as Complex CrimeDocument19 pagesEnrile vs. Salazar Ruling on Rebellion as Complex CrimeMaricar VelascoNo ratings yet

- 1 - Tiglao V Manila RailroadDocument3 pages1 - Tiglao V Manila RailroadDanielle Palestroque SantosNo ratings yet

- Case Digest 3Document2 pagesCase Digest 3Jefferson A. dela Cruz100% (1)

- City of Cebu vs. Heirs of RubiDocument6 pagesCity of Cebu vs. Heirs of RubiJaysonNo ratings yet

- Ma. Vilma F. Maniquiz vs. Atty. Danilo C. Emelo A.C. No. 8968, September 26, 2017 FactsDocument2 pagesMa. Vilma F. Maniquiz vs. Atty. Danilo C. Emelo A.C. No. 8968, September 26, 2017 FactsEduardNo ratings yet

- RTC and CA Orders ReversedDocument2 pagesRTC and CA Orders ReversedChaGonzales0% (1)

- Penalber V RamosDocument5 pagesPenalber V RamosAleph JirehNo ratings yet

- MV TDocument2 pagesMV TRM DGNo ratings yet

- Julio Borbon, Pedro Villamor and B. Quitoriano For Appellant. Acting Attorney-General Reyes For AppelleeDocument3 pagesJulio Borbon, Pedro Villamor and B. Quitoriano For Appellant. Acting Attorney-General Reyes For AppelleeYvette TevesNo ratings yet

- Judge Aguilar DisqualifiedDocument2 pagesJudge Aguilar DisqualifiedMidzmar KulaniNo ratings yet

- DIGEST - People v. Crisostomo PDFDocument2 pagesDIGEST - People v. Crisostomo PDFAgatha ApolinarioNo ratings yet

- Law On Municipal Corporations: A. IntroductionDocument7 pagesLaw On Municipal Corporations: A. IntroductionPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Spec-Comm 2021 SimpuloDocument111 pagesSpec-Comm 2021 SimpuloPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Legal Consequences....Document16 pagesUnderstanding The Legal Consequences....Patatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Lecture ScreenshotsDocument43 pagesLecture ScreenshotsPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Translation TheoriesDocument4 pagesTranslation TheoriesPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Langua GE Class: Bae Caponpon-Apostol Castro, L. MacayDocument36 pagesLangua GE Class: Bae Caponpon-Apostol Castro, L. MacayPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- MECARAL v. VelasquezDocument1 pageMECARAL v. VelasquezRicardo Jr RiboNo ratings yet

- Legarda VS CaDocument8 pagesLegarda VS CaPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- 23 (C) COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS Section 2Document2 pages23 (C) COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS Section 2Patatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Commission On Elections vs. Silva, JRDocument1 pageCommission On Elections vs. Silva, JRcsalipio24No ratings yet

- ART 114. 11. P V PerezDocument1 pageART 114. 11. P V PerezGin FernandezNo ratings yet

- 30 (C) COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS Section 3Document3 pages30 (C) COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS Section 3Patatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- People V VenturaDocument24 pagesPeople V VenturaPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Title Two Crimes Against The Fundamental Laws of The State: Article 124. Arbitrary DetentionDocument8 pagesTitle Two Crimes Against The Fundamental Laws of The State: Article 124. Arbitrary DetentionglaiNo ratings yet

- Title 1 National SecurityDocument8 pagesTitle 1 National SecurityFreidrich Anton BasilNo ratings yet

- Display PDFDocument23 pagesDisplay PDFtulika dixitNo ratings yet

- Total or Absolute, or Partial or Relative Repeal - ÏÏÏÏÏ Ï ÏDocument94 pagesTotal or Absolute, or Partial or Relative Repeal - ÏÏÏÏÏ Ï ÏMerlyn UchayanNo ratings yet

- Case Digests On Arts 247 248 249Document35 pagesCase Digests On Arts 247 248 249Jenaro CabornidaNo ratings yet

- Gender Based Violence - Power, Use of Force, and Consent ModuleDocument3 pagesGender Based Violence - Power, Use of Force, and Consent ModulegabriellejoshuaramosNo ratings yet

- People Vs Puno-GR No. 97471Document2 pagesPeople Vs Puno-GR No. 97471george almedaNo ratings yet

- Rape and Homicide Conviction Upheld for Foreign National Who Sexually Assaulted MinorDocument13 pagesRape and Homicide Conviction Upheld for Foreign National Who Sexually Assaulted MinorEnna Jane VillarinaNo ratings yet

- Legal Analysis of MurderDocument2 pagesLegal Analysis of MurderMarkus AureliusNo ratings yet

- English PracticeDocument1 pageEnglish PracticeMiguel Poma CuevaNo ratings yet

- 3rd CaseDocument11 pages3rd CaseAshley Kate PatalinjugNo ratings yet

- Darrell SmithDocument3 pagesDarrell SmithsamtlevinNo ratings yet

- Ra 623 PDFDocument1 pageRa 623 PDFJustin MoretoNo ratings yet

- People v. QuimzonDocument14 pagesPeople v. QuimzonKim Jona Peralta Castillo100% (2)

- Clay County Internet Cafe RegulationsDocument7 pagesClay County Internet Cafe RegulationsThe Florida Times-UnionNo ratings yet

- People V DasigDocument8 pagesPeople V DasigtimothymaderazoNo ratings yet

- Online Scams and Frauds During Covid 19Document17 pagesOnline Scams and Frauds During Covid 19RaghavNo ratings yet

- Robert William FisherDocument1 pageRobert William FisherDanny ShapiroNo ratings yet

- Cityscapes New Settlement Options For The Pathfinder RPG OEF2012Document19 pagesCityscapes New Settlement Options For The Pathfinder RPG OEF2012Max Prach NakawarangkulNo ratings yet

- CJ Critical Thinking - Gun Control 1Document9 pagesCJ Critical Thinking - Gun Control 1api-510706791No ratings yet

- Feasibility Study For Starting Up A Computer Training CentreDocument6 pagesFeasibility Study For Starting Up A Computer Training CentrePerpetuoNo ratings yet

- C.R. P No. 167/2012 in Suo Motu Case No. 5 of 2012Document17 pagesC.R. P No. 167/2012 in Suo Motu Case No. 5 of 2012MYOB420No ratings yet

- NYC DOI's Investigation Into NYPD Response To The George Floyd ProtestsDocument115 pagesNYC DOI's Investigation Into NYPD Response To The George Floyd Protestsbradlanderbrooklyn100% (1)

- United States v. Ducoing, 30 F.3d 127, 1st Cir. (1994)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Ducoing, 30 F.3d 127, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Evidence Case DigestDocument48 pagesEvidence Case DigestClark InovejasNo ratings yet

- Legmed Case DigestsDocument12 pagesLegmed Case DigestsAngelica PulidoNo ratings yet