Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(Ref - Platinum's Refractory Nature Towards Borax) William Brownrigg and His Scientific Work

Uploaded by

Nones NoneachOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(Ref - Platinum's Refractory Nature Towards Borax) William Brownrigg and His Scientific Work

Uploaded by

Nones NoneachCopyright:

Available Formats

The First Experiments on Platinum

WILLIAM BROWNRIGG AND HIS SCIENTIFIC WORK

By J. Russell-Wood, M.SC., Pm.

Upon thc whoic, this Semi metai feems a very

fingular Body, that merits au exatter Inquiry into

its Xature than hath hithcrro becn made; iince i t

js not altosether improbable, that, !ike the hlfdenet,

Iron, Antimony, Mercury, and other metallic Sub-

fiances, it may be endowed with Come pecubarQua-

fities, that may render it of Gngul~rUk acd Import-

ance to Mankind.

The history of the discovery of platinum in sister, Jemima, who later married Charles

the Spanish American colony of New Granada Wood, the assay master whose part in the

has been well told by McDonald in recent story will be told later.

issues of this journal. The first published Little is known about thc early education of

reference to the existence of this new metal Brownrigg. He appears to have been appren-

was in 1748, when there appeared in Madrid ticed to a surgeon in Whitehaven and to have

Don Antonio de Ulloa’s account of his studied in London from 1733 to 1735. Later,

voyage and explorations, but the interest of he went to Leyden to study “physic”, anatomy,

the scientific world was not aroused until botany and experimental philosophy, and he

specimens of platinum in its native state had graduated in 1737 as Doctor of Medicine on

arrived in Europe and had been submitted presentation of a thesis cntitled “De Praxis

to examination by qualified persons able to Medica Ineunda” in which he discussed the

report their findings adequately. state of the air, climate, and various other

The first such experimental work forms the contingencies affecting the locality where a

basis for this story, linking a quiet, shy physician proposed to reside.

country doctor living in Cumberland and Brownrigg settled in Whitehaven as a

giving his spare time to scientific researches, physician in 1737. He kept an extremely neat

his sister’s husband employed as an assay and painstaking case-book, which is now in

master in Jamaica, and the distinguished the library of Tullie House, Carlisle. On

London scientist Sir William Watson. August 3rd, 1741, he married Mary, the

William Brownrigg, the central figure of daughter of John Spedding of Whitehaven.

this narrative, spent practically the whole of In I742 he was elected a Fellow of the

his working life in Cumberland. The gene- Royal Society, subsequent to the reading of

alogy of the family starts with Gawen his paper on the mineral exhalations from the

Brownrigg, who lived in the time of Henry poisonous lakes at Avernie, which paper had

VII at the head of Lake Derwentwater. His induced Sir Hans Sloane and Dr Stephen

two great-great-grandsons were William, HaIes to advise Brownrigg to prepare a

born at High Close Hall on March 24th, general history of “damps”. In 1766 Brown-

1711, and his brothcr George, who later rigg was awarded the Copley medal, the

emigrated to America. There was also a highest award of the Royal Society, for his

Platinum Metals Rev., 1961, 5, (2), 66-69 66

experimental work on the waters of Spa, in work on “dephlogisticated air” that led to the

Germany, as being the best original publica- overthrow of the phlogiston theory of com-

tion of the year, He showed that these waters bustion by Lavoisier and the introduction of

owed their sharp taste to the presence of the oxygen theory, although Priestley himself

carbon dioxide, hence the possibility of was a confirmed phlogistonist right up to his

making such waters artificially. This work death. But all the different gases known were

gave Brownrigg an acknowledged name in considered as ordinary air contaminated with

science. impurities, and the very word “gas”, which

had been used earlier by Van Helmont, was

Eighteenth-Century Chemistry avoided by English chemists. A new method

During the period of Brownrigg’s life, a of distillation had been introduced by Hales

closer association developed between “pure” which consisted in blowing air through the

and “applied” science. Great advances were heated liquid undergoing distillation. Woulfe

made in pneumatic chemistry by Priestley (of Woulfe bottle fame) distilled substances

on oxygen, sulphur dioxide and other gases, such as common salt and sulphuric acid and

b y Cavendish on hydrogen and by Black on absorbed the volatile product in water. Much

carbon dioxide. It was, indeed, Priestley’s work was done on natural waters, primarily to

Born in Cuinberland two

hundred and jifiy years ago,

William Brownrigg combined

a distinguished scientific career

with a modest and retiring

nature. Among his numerous

contributions to eighteenth-cen-

tury chemistry were the first

experiments to be carried out

on the properties of platinum,

reported LO the Royul Society i n

1750 by his friend Sir William

Watson. The rovering letter

from Brownrig& published i n

the Philosophzeal Transac-

tions of the Royal Society, is

reproduced here

Platinum Metals Rev., 1961, 5, ( 2 ) 67

find an explanation of their medicinal of the pommel of a sword. These he brought

properties. home to England and gave to his brother-in-

The eighteenth century was a quiet time, law, Brownrigg. It was not until nine years

atomically, after the fervour of the cor- later-December Sth, 17p-that Brownrigg

puscular theory. Emphasis was still laid on passed these specimens on to the Royal

the shape and size of atoms, but a new con- Society, together with his historic letter,

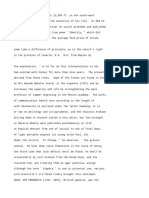

cept of forces being lodged in atoms was through the good offices of his friend William

adopted. There was little to be found in the Watson. The first page of his covering

applied chemistry of the seventeenth century letter to Watson is reproduced on the previous

that did not have its origins in early Egyptian page-

civilisations, although techniques may have Apparently it was Charles Wood, described

improved. But in the first half of the eighteenth by his brother-in-law as “a skilful and inquisi-

century great advances were made in this tive metallurgist”, who, at Brownrigg’s insti-

direction; for instance, Le Blanc originated gation, carried out certain of the experiments,

the soda industry and Brownrigg himself put but Brownrigg himself conducted some of

forward suggestions for making cheaper and the earlier tests, while he also repeated

better salt, partly to help the British fishing Wood’s experiments a little later, giving an

industry, which had been hard hit by the account of them in a further letter to the

War of the Austrian Succession, and partly Royal Society dated February 13th, 1751.

to improve the health of the nation. In the first letter Brownrigg described how

The quantitative aspect of chemistry was he had come into possession of the samples

being realised. Lavoisier, in his work on the of platinum and went on: “It is found in

fermentation of sugar solutions, insisted that considerable quantities in the Spanish West

a chemical reaction could be postulated as an Indies (in what part I could not learn) and is

algebraic equation, a clear assertion that the there known by the name of Platina di Pinto.

Law of Conservation of Mass applied to a The Spaniards probably call it Platina from

chemical reaction. Improvements were made the resemblance in colour that it bears to

in the collection of gases; Brownrigg himself silver. It is bright and shining, and of a

introduced a method of collecting gases by uniform texture; it takes a fine polish, and is

fixing a squeezed bladder to the neck of a not subject to tarnish or rust; it is extremely

flask containing substances which would hard and compact; but, like bath-metal or

generate the gas. The teaching of chemistry cast iron, brittle, and cannot be extended

began to acquire more importance, freeing under the hammer.”

itself from superstition and ceasing to be a Brownrigg then went on to describe how

mere appendage to medical teaching. Against he kept platinum in an air furnace for two

such a background of knowledge Brownrigg hours “in a heat that would run down cast

did his work. iron in fifteen minutes” but it did not mclt,

nor did any melting take place if it were

The Samples of Platina mixed with borax and heated under the same

In 1741Charles Wood, in the course of his conditions. Brownrigg found that when

duties as assay master, acquired some samples platinum was heated with lead, silver, gold,

of “platina” which he was told came from copper or tin it readily formed a molten

Cartagena, the port of New Granada. They alloy which gave a hard and brittle solid on

consisted of a mixture of native platinum cooling; he found neither a change in weight

with black sand and other impurities as found nor any corrosion when the platinum was

in the mines, some native platinum separated heated with aqua regia for twelve hours.

from these impurities, some that had been “It appears,” he concluded, “that no known

fused, and another piece that formed part body approaches nearer to the nature of gold,

Platinum Metals Rev., 1961, 5, ( 2 ) 68

in its most essential properties of fixedness Christian gentleman. He made inquiries

and solidity, than the semi-metal here treated into fire-damp hoping that they might help

of; and that it also bears a great resemblance to solve the diseases to which miners were

to gold in other particulars. Some alchemists subject. His invention of better and cheaper

have thought that gold differed from other methods of making salt, referred to above,

metals in nothing so much as in its specific gave to England the great boon of having this

gravity; and that, if they could obtain a body commodity freed from all tax before the end

that had the specific weight of gold, they of the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

could easily give it all the other qualities of He was a founder member of the Whitehaven

that metal. Let them try their art on this dispensary, in 1783, the purpose of which was

body; which, if it can be made as ductile as “to alleviate the exquisite sufferings of

gold, will not easily be distinguished from disease, obviate its malignant tendency . . .

gold itself.” and interrupt its powerful communication”.

Brownrigg died on January 6th, 1800, and

Experiments on Cupellation was buried at Crosthwaite Church, near

In the second letter Brownrigg gave an Keswick. The Cumberland Pacquet of January

account of an experiment he made to show 14th referred to him in a memorial notice

that platinum did not resist the action of as “this venerable philosopher and physician

lead in cupellation, as he had hitherto . . . possessed of every excellent quality

thought. This led to a possibility of refining which could adorn the great and good”.

gold and silver containing platinum. He wrote: In an obituary notice in The Gentleman’s

“By adding to gr. xxvi of platina fifteen times Magazine reference is made to the President

its own weight of pure lead, that I had myself of the Royal Society’s remarks when present-

reduced from lithage. To the lead put into ing a gold medal to Priestley for his researches

a coppel, and placed in a proper furnace, as on the nature of air: “It is no disparagement

soon as it was melted I added the platina, to the learned D r Priestley that the vein of

which in a short time was dissolved in the these discoveries was hit upon . . . some

lead. After the lead was all wrought off, years ago by my very learned, very pene-

there remained at the bottom of the coppel a trating, very industrious, but too modest

pellet of platina, which I found to weigh only friend D r Brownrigg.”

gr. xxi; so that in this operation, the platina

had lost near a fifth part of its weight.” The Importance

Charles Wood had found, earlier, that the of Brownrigg’s Work

platinum had gained weight during the While Brownrigg’s actual contribution to

cupellation. Brownrigg says that “one Mr our knowledge of the properties of platinum

Ord, formerly a factor in the South Sea was not perhaps of major importance, he none

Company, took, in payment from some the less played a vital part, in that the publica-

Spaniards, gold to the value of E5oo sterling, tion of his findings in the PhilosophicaZ

which, being mixed with platina, was so Transactions of the Royal Society brought

brittle that he could not dispose of it, neither them to the notice of scientists throughout

could he get it refined in London, so that England and Europe. They thus led swiftly

it was quite useless to him; although, if on to the many other investigations, such as

no error hath been committed in the above- those carried out by Scheffer, Lewis, Marggraf,

mentioned experiment, it might probably Buffon, Achard, and later by Knight and

have been rendered pure by a much larger Wollaston, that firmly established the nature

dose of lead than is usually applied for that and characteristics of platinum. Possibly

purpose.” Brownrigg’s most significant comment was

Brownrigg was an extremely humane and that reproduced at the head of this article.

Platinum Metals Rev., 1961, 5, ( 2 ) 69

You might also like

- Ancient Egyptian NamesDocument6 pagesAncient Egyptian NamesDaniNo ratings yet

- Carburizing, Nitriding, and Boronizing in Vacuum Furnaces - IpsenDocument9 pagesCarburizing, Nitriding, and Boronizing in Vacuum Furnaces - Ipsenarkan1976No ratings yet

- Acc1789 9165Document4 pagesAcc1789 9165Kimchee StudyNo ratings yet

- DebereinerDocument4 pagesDebereinerRSLNo ratings yet

- OxygenDocument6 pagesOxygenSrijay SutarNo ratings yet

- Math6668 7707Document4 pagesMath6668 7707safitribilbinaarNo ratings yet

- Nature: 136, 468, 521 1935) and at TheDocument2 pagesNature: 136, 468, 521 1935) and at TheOscar Del Valle ValdespinoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledDon RatbuNo ratings yet

- Eco5852 8102Document4 pagesEco5852 8102CourseHero ni Kray at KenNo ratings yet

- Acc4610 761Document4 pagesAcc4610 761Reynheart Joy RedondoNo ratings yet

- Math2472 4643Document4 pagesMath2472 4643мεттѕнυ εαvσͷNo ratings yet

- Eng7589 1107Document4 pagesEng7589 1107falenixyNo ratings yet

- Econ4822 9421Document4 pagesEcon4822 9421Mia Mikasa69No ratings yet

- Eco9406 8228Document4 pagesEco9406 8228HariyadiNo ratings yet

- Math2341 7840Document4 pagesMath2341 7840IvanwbsnNo ratings yet

- Moore 1921Document53 pagesMoore 1921Cristina Spolti LorenzettiNo ratings yet

- Eng5357 3516Document4 pagesEng5357 3516Tasya axNo ratings yet

- Psy8887 8611Document4 pagesPsy8887 8611dsjdjxjxNo ratings yet

- Math1364 6703Document3 pagesMath1364 6703Manguilimotan, Sean Quincy C.No ratings yet

- Science4557 7269Document4 pagesScience4557 7269Fajar AlfNo ratings yet

- Econ8205 6926Document4 pagesEcon8205 6926Ernesto Contreras ChambergoNo ratings yet

- Acc4414 7417Document4 pagesAcc4414 7417ChannelRazorTVNo ratings yet

- Eng4880 2049Document4 pagesEng4880 2049Harry LubisNo ratings yet

- Eco9786 8967Document4 pagesEco9786 8967AntoniusAdiPutraUtamaNo ratings yet

- Econ4101 6891Document4 pagesEcon4101 6891Ayu TriyantiNo ratings yet

- Acc9500 2259Document4 pagesAcc9500 2259Noodles CaptNo ratings yet

- Eco2172 2091Document4 pagesEco2172 2091Muntakia SultanaNo ratings yet

- Phys5377 8500Document4 pagesPhys5377 8500line korNo ratings yet

- Bio9370 5823Document4 pagesBio9370 5823Arvin FernandezNo ratings yet

- Phys7109 1890Document4 pagesPhys7109 1890bps kotadepokNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Town1697 - 6131Document4 pagesBeautiful Town1697 - 6131Kisalaya KishoreNo ratings yet

- Phys 8136Document4 pagesPhys 8136Mamam blueNo ratings yet

- The Hare-Clarke Controversy Over The Invention of The Improved Gas BlowpipeDocument6 pagesThe Hare-Clarke Controversy Over The Invention of The Improved Gas BlowpipeCharles JacobNo ratings yet

- Eco582 9503Document4 pagesEco582 9503Dinda SaddonoNo ratings yet

- Bio4211 9708Document4 pagesBio4211 9708Biruh TesfaNo ratings yet

- Acc5959 8078Document4 pagesAcc5959 8078Nezer VergaraNo ratings yet

- Sigismond BacstromDocument61 pagesSigismond BacstromluxmundiNo ratings yet

- Chem474 8146Document4 pagesChem474 8146Jus ReyesNo ratings yet

- Eco3711 2391Document4 pagesEco3711 2391kakaoNo ratings yet

- Chem5784 5112Document4 pagesChem5784 5112Aiman Danish Bin Mohd. Taufik TohNo ratings yet

- Chem1047 1894Document4 pagesChem1047 1894Juan Alcazar RomeroNo ratings yet

- Beginnings: Into The Valley' Into The Valley With Mothers With All!Document3 pagesBeginnings: Into The Valley' Into The Valley With Mothers With All!aNo ratings yet

- Acc7066 9555Document4 pagesAcc7066 9555Allen NyorkzNo ratings yet

- Physics 536Document4 pagesPhysics 536Zaice MontemoréNo ratings yet

- Ind604 1478Document4 pagesInd604 1478mochi sidemNo ratings yet

- Keungan9906 6822Document4 pagesKeungan9906 6822Jinong JuNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Surg7819 - 8139Document4 pagesPediatric Surg7819 - 8139saraahmadNo ratings yet

- The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 19, No. 3. (Sep., 1924), Pp. 239-262Document24 pagesThe Scientific Monthly, Vol. 19, No. 3. (Sep., 1924), Pp. 239-262Shelagh RoseNo ratings yet

- Eng1467 5379Document4 pagesEng1467 5379joey FajardoNo ratings yet

- Soc5412 1362Document4 pagesSoc5412 1362honda semakin di depanNo ratings yet

- Em17 2253Document4 pagesEm17 2253Arjelyn MonteroNo ratings yet

- Dolan Embodied Skills2003Document27 pagesDolan Embodied Skills2003Sima Sorin MihailNo ratings yet

- Acc3013 5913Document4 pagesAcc3013 5913Test AccountNo ratings yet

- Bio1715 5251Document4 pagesBio1715 5251Ahmed MohamedNo ratings yet

- Eng6411 1819Document4 pagesEng6411 1819bebeNo ratings yet

- Psy4043 4402Document4 pagesPsy4043 4402Nafees ul HassanNo ratings yet

- Eco9191 4901Document4 pagesEco9191 4901RuskiNo ratings yet

- Acc3013 5918Document4 pagesAcc3013 5918Test AccountNo ratings yet

- THEISEN, Wilfrid. The Attraction of Alchemy For Monks and Friars in The 13th-14th Centuries PDFDocument15 pagesTHEISEN, Wilfrid. The Attraction of Alchemy For Monks and Friars in The 13th-14th Centuries PDFMariana CantuariaNo ratings yet

- Blood and Soil in Narendra Modis IndiaDocument30 pagesBlood and Soil in Narendra Modis IndiaNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- How To Decimate A City - The AtlanticDocument19 pagesHow To Decimate A City - The AtlanticNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Sourcing MaterialsDocument5 pagesSourcing MaterialsNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Regular ExpressionsDocument197 pagesRegular ExpressionsCarlos Brando100% (4)

- Confederation The One Possible Israel-PalestinenbspSolutionDocument11 pagesConfederation The One Possible Israel-PalestinenbspSolutionNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- There Is A Life Behind Every Statistic' LRB BlogDocument19 pagesThere Is A Life Behind Every Statistic' LRB BlogNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Bees Are The Overseers Poem - Rikki Ducornet - With Allan Kausch Art Numéro CinqDocument4 pagesBees Are The Overseers Poem - Rikki Ducornet - With Allan Kausch Art Numéro CinqNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Fetch The Scissors - Bs Johnson - LRBDocument8 pagesFetch The Scissors - Bs Johnson - LRBNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- East Chisenbury - Ritual and Rubbish atDocument9 pagesEast Chisenbury - Ritual and Rubbish atNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- 01 - WasteStream - Garbage ProjectDocument16 pages01 - WasteStream - Garbage ProjectNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- The Santa Fe Homeless Backpack ProjectDocument4 pagesThe Santa Fe Homeless Backpack ProjectNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- KHOURYDocument2 pagesKHOURYNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 07 06994Document17 pagesSustainability 07 06994Anita MarquezNo ratings yet

- A Look Back at The History of The FenceDocument2 pagesA Look Back at The History of The FenceNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- The Business of Religion in An Iconic Department StoreDocument345 pagesThe Business of Religion in An Iconic Department StoreNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Escalators: Laura Fleissner AmmonDocument10 pagesEscalators: Laura Fleissner AmmonNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- WorkerbeeDocument1 pageWorkerbeeNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- BERDYAEVDocument2 pagesBERDYAEVNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Peterchrisp - Blogspot.co - Uk-Our Annotated WakesDocument11 pagesPeterchrisp - Blogspot.co - Uk-Our Annotated WakesNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Meister EckhartDocument2 pagesMeister EckhartNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Spagyric Elevator - Read This SoonDocument9 pagesSpagyric Elevator - Read This SoonNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- GOLDMANDocument3 pagesGOLDMANNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Alternative Modernities - Dilip Parameshwar GaonkarDocument374 pagesAlternative Modernities - Dilip Parameshwar GaonkarNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- The Ontological Foundations of The Debate Over OriginalismDocument75 pagesThe Ontological Foundations of The Debate Over OriginalismNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Carpet Glossary A To C - Carpet Encyclopedia - Carpet EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesCarpet Glossary A To C - Carpet Encyclopedia - Carpet EncyclopediaNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Originalism - A Critical IntroductionDocument36 pagesOriginalism - A Critical IntroductionNones Noneach100% (1)

- ST Kilda and Other Hebridean Outliers - Francis ThompsonDocument220 pagesST Kilda and Other Hebridean Outliers - Francis ThompsonNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Pages From Korean Folk TalesDocument2 pagesPages From Korean Folk TalesNones NoneachNo ratings yet

- Casting For 2023 GATE ESE PSUs by S K MondalDocument71 pagesCasting For 2023 GATE ESE PSUs by S K Mondalphineasandferb786No ratings yet

- Meija 2014 Adición EstándarDocument5 pagesMeija 2014 Adición EstándarDïö ValNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument16 pagesIntroductionAkhtar RazaNo ratings yet

- Brain Targeting Drug Delivery SystemDocument35 pagesBrain Targeting Drug Delivery SystemOmotoso KayodeNo ratings yet

- Innovations in GMA Acrylic Powder CoatingsDocument5 pagesInnovations in GMA Acrylic Powder CoatingsOrlandoNo ratings yet

- Paints and CoatingsDocument28 pagesPaints and CoatingsMaximiliano MackeviciusNo ratings yet

- API en - Atm.co2e.pc Ds2 en Excel v2 2764338Document28 pagesAPI en - Atm.co2e.pc Ds2 en Excel v2 2764338Lion HunterNo ratings yet

- Venturi Nozzle Systems Questions and AnswersDocument1 pageVenturi Nozzle Systems Questions and Answersbalaji12031988No ratings yet

- MSDS AspirinDocument7 pagesMSDS AspirinNyana ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- Aflas EngDocument11 pagesAflas EngVictor Flores ResendizNo ratings yet

- D 2111 - 02 - RdixmteDocument4 pagesD 2111 - 02 - RdixmteRuben YoungNo ratings yet

- Materials Studio Paper ImportantDocument11 pagesMaterials Studio Paper ImportantMd.Helal Hossain100% (1)

- NaOH Practicality StudyDocument51 pagesNaOH Practicality StudyPeterWangNo ratings yet

- Acm Instruments BrochureDocument12 pagesAcm Instruments BrochuresoldadouniverNo ratings yet

- Sicilian Lemon OilDocument12 pagesSicilian Lemon OilbabithyNo ratings yet

- Metal Based PackagingDocument21 pagesMetal Based PackagingSheraz KarimNo ratings yet

- Dislocations and Plastic DeformationDocument6 pagesDislocations and Plastic DeformationPrashanth VantimittaNo ratings yet

- Slake Durability TestDocument7 pagesSlake Durability TestIkhwan Z.100% (2)

- Fully Automated Determination of TAN/TBN in Industrial Samples According To ASTM Standards D 664 and D 2896Document1 pageFully Automated Determination of TAN/TBN in Industrial Samples According To ASTM Standards D 664 and D 2896Wilber AraujoNo ratings yet

- Laue EquationsDocument3 pagesLaue EquationsVinodh SrinivasaNo ratings yet

- Sulphide Deposits-Their Origin and Processing James R. Craig, David J. Vaughan (Auth.), P. M. J. Gray, G. J. Bowyer, J. F. Castle, D. J. Vaughan, N. A. Warner (Eds.)Document302 pagesSulphide Deposits-Their Origin and Processing James R. Craig, David J. Vaughan (Auth.), P. M. J. Gray, G. J. Bowyer, J. F. Castle, D. J. Vaughan, N. A. Warner (Eds.)NSchoolmeesters_1359100% (1)

- Genious of HomeopathyDocument194 pagesGenious of HomeopathyAli AkbarNo ratings yet

- Referentne ElektrodeDocument26 pagesReferentne ElektrodeZlata JašarevićNo ratings yet

- Organic Chemistry 6 Edition: Elimination Reactions of Alkyl Halides Competition Between Substitution and EliminationDocument65 pagesOrganic Chemistry 6 Edition: Elimination Reactions of Alkyl Halides Competition Between Substitution and Eliminationpawan kumar guptaNo ratings yet

- Fluid Mechanics Ii (Meng 3306) : Worksheet 1 Chapter1. Potential Flow TheoryDocument4 pagesFluid Mechanics Ii (Meng 3306) : Worksheet 1 Chapter1. Potential Flow TheoryAddisu DagneNo ratings yet

- MEEG 321 Homework 1 2018Document2 pagesMEEG 321 Homework 1 2018Abu Jafar RaselNo ratings yet

- Frank W Seeberger WWW - Educhem.Eu The Clausius-Clapeyron Equation 1 / 8Document8 pagesFrank W Seeberger WWW - Educhem.Eu The Clausius-Clapeyron Equation 1 / 8Ossama BohamdNo ratings yet

- Worksheet - 1 - Metals and Non MetalsDocument2 pagesWorksheet - 1 - Metals and Non MetalsSOULSNIPER 15No ratings yet

- Ansi A13.1 1996Document13 pagesAnsi A13.1 1996Marco VeraNo ratings yet