Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journals Arab 40 1 Article-P84 4-Preview

Journals Arab 40 1 Article-P84 4-Preview

Uploaded by

Zoheb RehanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journals Arab 40 1 Article-P84 4-Preview

Journals Arab 40 1 Article-P84 4-Preview

Uploaded by

Zoheb RehanCopyright:

Available Formats

ON THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE

MEANING OF ZAK�T IN EARLY ISLAM

BY

SULIMAN BASHEAR

Introduction

HE INFORMATION provided by Muslim sources on zakatlsadaqa

T(poor-tax/rate, almsgiving), which eventually emerged as one

of the "pillars" (arkan) of classical Islam, has been outlined by

modern scholars. While the voluntary vs. obligatory nature of

zakdtlsadaqa and their interchangeable occurrence in these sources

were considered, it has also been noted that, in the time of the

Prophet, these were still vague regulations and did not represent

taxes demanded by religion. Widely circulated reports concerning

the refusal of certain Bedouin tribes to pay zakat after the Prophet's s

death as they considered their agreements with him cancelled by

that, as well as 'Umar's inclination to agree with this, and the fact

that only Abu Bakr made it a permanent institution, were brought

in support of such an assessment. I

The basic difference between sadaqa, which was primarily applied

to the supererogatory, and the obligatory nature of zakdt, has also

been noted.2 And the eventual emergence of alms as an obligatory

duty in Islam led one scholar, H. Grimme, to the suggestion that

Muhammad "should be treated as a social rather than a religious

reformer.' R. Bell, in turn, gave weight to the fact that the order

to pay zakat occurs in "Meccan passages" of the and noted

that such occurrence comes "only in the sense of alms and volun-

tary giving to the poor, as much for the purification of the giver's

1 Schacht, s.v. "Zak�t" in

J. Encyclopaediaof Islam, first edition, IV, 1202-4;

H.A.R. Gibb and J. Kramers, eds., ShorterEncyclopaedia of Islam,Leiden 1974, pp.

654-5, and the sources cited therein.

2 E. Lane,

Arabic-EnglishLexicon,repr. Beirut 1980, IV, p. 1668.

3 H. Grimme, Mohammed,Münster 1892,

quoted by Tor Andrae, Mohammed,

the Man and His Faith, London 1936, pp. 101-2; and R. Bell, The Origin of Islam

in its Christian Environment,London 1926, p. 79.

85

soul as for relief of the needy. "4 Concerning the institution of zakat,

which is nowhere regulated, J. Schacht cautiously pointed to the

fact that Muslim sources place it in Medina between the years 2 and

9 A.H., while R. Bell sounds more confident when saying that "its

beginning belongs to the first year or two in Medina and was

motivated by the circumstances of the poorer Muhajirun and

necessities of the state.' `5 5

Scholars also disagreed concerning the similarity between and

possible origins of zakat and sadaqa in parallel institutions and

cognate words from the vocabulary of other religions in the area.

R. Bell held that "the word zakat is Syriac and therefore Chris-

tian", but J. Schacht and others expressed the view that it was bor-

rowed from Jewish usage of Hebrew-Aramaic zdkzit. 6 And the same

was held concerning sadaaa as a transliteration of the Hebrew sedaka

which originally meant "honesty". We are also told that, as

applied by the Pharisees for what they considered the chief duty of

the pious Israelites, namely almsgiving, the proper sense of this

word, which is voluntary or spontaneous "charity", was still

retained at the time of the coming of Islam and elsewhere.' One

scholar, H.P. Smith, held that Muslim tazkiya in the sense of

purification of property corresponds to a similar notion expressed

in Deuteronomy 14:28, though, later, zakdt emerged as a regular tax

of the Muslim State.8 C.C. Torrey, in turn, expressed the view that

zakat and sadaqa are loan words from the North Semitic languages,

corresponding in particular to Aramaic zakut and sidakta and

Hebrew sidaka, respectively. The Aramaic words, he held,

originally meant "purity" and were used by both Jews and Chris-

tians in the sense of "virtuous conduct". To this he added the view

that "the latter term (?idakta) was widely used in Aramaic speech

to mean alms. "9 9

4 R. Bell, Introductionto the

Qur¸�n,Edinburgh 1953, p. 166. Cf. also M.

Hudgson, The Ventureof Islam, Chicago 1974, p. 181.

5 J. Schacht, p. 1203; R. Bell, ibid.

6 J. Schacht, p. 1202; H.A.R. Gibb and J.H. Kramers, p. 654. Compare, how-

ever, with A. Jeffery, Foreign Vocabularyof the Qur¸�n,Baroda 1938, p. 153, where

it is stated that neither of the Aramaic or Syriac cognates seem to have ever meant

alms, though this meaning could easily be derived from them.

7 H.A.R. Gibb and J.H. Kramers, ibid.

8 H.P. Smith, The Bible and Islam, N.Y. 1897, p. 313.

9 C.C. Torrey,

The Jewish Foundationof Islam, N.Y. 1933, p. 141.

You might also like

- The Accepted Whispers by Shaykh Ashraf Ali ThanviDocument178 pagesThe Accepted Whispers by Shaykh Ashraf Ali Thanviعاجز احمد100% (1)

- Religious Culture in Late Antique Arabia PDFDocument371 pagesReligious Culture in Late Antique Arabia PDFiftisweltNo ratings yet

- The First Written Constitution of The WorldDocument45 pagesThe First Written Constitution of The WorldAMEEN AKBAR100% (2)

- Is Petra Islam's True BirthplaceDocument6 pagesIs Petra Islam's True BirthplaceIjaz Ahmad100% (1)

- HawaryDocument13 pagesHawaryYusup RamdaniNo ratings yet

- Defining Boundaries in al-Andalus: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Islamic IberiaFrom EverandDefining Boundaries in al-Andalus: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Islamic IberiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- On The Origins & Development of The Meaning of Zakat Suliman BashearDocument31 pagesOn The Origins & Development of The Meaning of Zakat Suliman Bashearasadghalib1No ratings yet

- Ahmed El-Wakil - The Prophet's Treaty With The Christians of NajranDocument82 pagesAhmed El-Wakil - The Prophet's Treaty With The Christians of NajranMario ŠainNo ratings yet

- Islamic Identity and The Ka Ba-: Alāt Move With One Motion, WithoutDocument16 pagesIslamic Identity and The Ka Ba-: Alāt Move With One Motion, WithoutŽubori PotokNo ratings yet

- Writing The Biography of The Prophet Muhammad: Problems and SolutionsDocument22 pagesWriting The Biography of The Prophet Muhammad: Problems and Solutionsycherem1978No ratings yet

- American Oriental Society Journal of The American Oriental SocietyDocument22 pagesAmerican Oriental Society Journal of The American Oriental SocietyMelangell Shirley Roe-Stevens SmithNo ratings yet

- The Ummi Prophet and The Banu Israil of The Qur'AnDocument6 pagesThe Ummi Prophet and The Banu Israil of The Qur'AnAfzal Sumar100% (1)

- New Doc Texts and The Earlu Islamic State - HoylandDocument22 pagesNew Doc Texts and The Earlu Islamic State - Hoylandsarabaras100% (1)

- Hoyland, New Documentary Texts PDFDocument22 pagesHoyland, New Documentary Texts PDFMo Za PiNo ratings yet

- Muhammad's Inspiration by JudaismDocument14 pagesMuhammad's Inspiration by JudaismCheradenine75% (4)

- The Identity of The SabiunDocument15 pagesThe Identity of The SabiunFaris Abdel-hadiNo ratings yet

- Companions of The Prophet - Encyclopaedia of The Qur'an, Vol. 1 (Brill, 2001)Document5 pagesCompanions of The Prophet - Encyclopaedia of The Qur'an, Vol. 1 (Brill, 2001)David BaileyNo ratings yet

- The Monk Encounters The Prophet - The Story of The Encounter Between Monk Bahira and Muhammad As It Is Recorded in The Syriac Manuscript of Mardin 259-2Document9 pagesThe Monk Encounters The Prophet - The Story of The Encounter Between Monk Bahira and Muhammad As It Is Recorded in The Syriac Manuscript of Mardin 259-2Joao Vitor LimaNo ratings yet

- An Interpretation of the Qur'an: English Translation of the MeaningsFrom EverandAn Interpretation of the Qur'an: English Translation of the MeaningsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- CreedsDocument56 pagesCreedsHailé SzelassziéNo ratings yet

- Perlman N 1942Document20 pagesPerlman N 1942Jason Phlip NapitupuluNo ratings yet

- Qibla Musharriqa BashearDocument16 pagesQibla Musharriqa BashearSriNaharNo ratings yet

- CH 3 Christian-Muslim Relations-1Document10 pagesCH 3 Christian-Muslim Relations-1awaimeraNo ratings yet

- Spice ModuleDocument30 pagesSpice Modulepagol_23_smhNo ratings yet

- In The Court of Ya'qūb Ibn Killis A Fragment From The Cairo GenizahDocument33 pagesIn The Court of Ya'qūb Ibn Killis A Fragment From The Cairo Genizahאליעזר קופערNo ratings yet

- Fitra Ibn HazmDocument20 pagesFitra Ibn HazmSo' FineNo ratings yet

- Polemics Muslim JewishDocument8 pagesPolemics Muslim JewishR HardiantNo ratings yet

- Sufism ArberryDocument27 pagesSufism ArberryNada SaabNo ratings yet

- Syrian CHRSTDocument214 pagesSyrian CHRSTHüseyin VarolNo ratings yet

- KHAN GEOFFREY 15-OrSymp 2016 The Karaites and The Hebrew BibleDocument24 pagesKHAN GEOFFREY 15-OrSymp 2016 The Karaites and The Hebrew Bibleivory2011No ratings yet

- Jerusalem in Early IslamDocument23 pagesJerusalem in Early IslamvordevanNo ratings yet

- 1st ChroniclesDocument40 pages1st Chroniclesxal22950No ratings yet

- History Compass - 2007 - HoylandDocument22 pagesHistory Compass - 2007 - HoylanddamnationNo ratings yet

- (Lies Rebuttal Series) Was Uzayr (Ezra) Called The Son of GodDocument5 pages(Lies Rebuttal Series) Was Uzayr (Ezra) Called The Son of Godabuali-almaghribi100% (2)

- Yemen and Early Islam by Suliman BashearDocument36 pagesYemen and Early Islam by Suliman BashearasadmarxNo ratings yet

- Weiner BibDocument6 pagesWeiner Bibiskandar.hai2226No ratings yet

- Suliman BashearDocument36 pagesSuliman BashearDrawUrSoulNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Al-BaqirDocument3 pagesMuhammad Al-BaqirShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- The Fast of Ashura - Allamah Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi - XKPDocument8 pagesThe Fast of Ashura - Allamah Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi - XKPIslamicMobilityNo ratings yet

- Kāhin - Brill ReferenceDocument5 pagesKāhin - Brill ReferenceJawad QureshiNo ratings yet

- Kitab - Al Burhan of Ammar - Al - Basri - An - AraDocument29 pagesKitab - Al Burhan of Ammar - Al - Basri - An - AraNjono SlametNo ratings yet

- QIBLA MUSHARRIQA AND EARLY MUSLIM PRAYER IN CHURCHES by Suliman BashaerDocument17 pagesQIBLA MUSHARRIQA AND EARLY MUSLIM PRAYER IN CHURCHES by Suliman BashaerasadmarxNo ratings yet

- ARTS017 Tutorials - Notes - On History of ArabiaDocument2 pagesARTS017 Tutorials - Notes - On History of ArabiaAfshan RahmanNo ratings yet

- A Holy Heretical Body Ala B. Ubayd AlDocument33 pagesA Holy Heretical Body Ala B. Ubayd AlLalaylaNo ratings yet

- Badawi Qurans Connection With SyriacDocument35 pagesBadawi Qurans Connection With SyriacWillSmathNo ratings yet

- HUMSS 1 L Lesson 6Document12 pagesHUMSS 1 L Lesson 6John Demice V. Hidas100% (1)

- Munt SOAS No Two ReligionsDocument21 pagesMunt SOAS No Two Religionshappycrazy99No ratings yet

- Christian Monks in Islamic Literature: A Preliminary Report On Some ArabicDocument19 pagesChristian Monks in Islamic Literature: A Preliminary Report On Some ArabicArtur SantosNo ratings yet

- The Book of AbrahaM and The Islamic Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyā (Tales of The Prophets) Extant LiteratureDocument21 pagesThe Book of AbrahaM and The Islamic Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyā (Tales of The Prophets) Extant LiteratureMerveNo ratings yet

- Glimpses To A Genealogy of Sufi Heritage in The Poetry of Spanish American CultureDocument35 pagesGlimpses To A Genealogy of Sufi Heritage in The Poetry of Spanish American CultureIgnacio IñiguezNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Christians of the Early Centuries of Christianity according to a New Source- היהודים-הנוצרים במאות הראשונות של הנצרות על פי מקור חדשDocument75 pagesThe Jewish Christians of the Early Centuries of Christianity according to a New Source- היהודים-הנוצרים במאות הראשונות של הנצרות על פי מקור חדשאליהו אלמני טוסיה100% (1)

- Christian-Muslim Diplomatic Relations AnDocument44 pagesChristian-Muslim Diplomatic Relations AnKhalilou BouNo ratings yet

- Early Muslim Relations With Christianity: David ThomasDocument5 pagesEarly Muslim Relations With Christianity: David ThomasShawki ShehadehNo ratings yet

- Nisaba: Religious Texts Translation SeriesDocument97 pagesNisaba: Religious Texts Translation Serieselmraksi30No ratings yet

- Ghulam Nabi Falahi Development of HadithDocument13 pagesGhulam Nabi Falahi Development of Hadithlatifshaikh20No ratings yet

- Religions: The Covenants of The Prophet and The Subject of SuccessionDocument13 pagesReligions: The Covenants of The Prophet and The Subject of SuccessionOsama HeweitatNo ratings yet

- Reflecting Divine Light - Em-Al-Khidr - em - As An Embodiment of Go PDFDocument15 pagesReflecting Divine Light - Em-Al-Khidr - em - As An Embodiment of Go PDFFazal Ahmed ShaikNo ratings yet

- Why Does The Quran Need The Meccan SanctDocument17 pagesWhy Does The Quran Need The Meccan SanctTonny OtnielNo ratings yet

- A CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVE ON ISLAM'S ORIGINS: Its Religion, Founder, an PracticesFrom EverandA CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVE ON ISLAM'S ORIGINS: Its Religion, Founder, an PracticesNo ratings yet

- Conversion, Circumcision, and Ritual Murder in Medieval EuropeFrom EverandConversion, Circumcision, and Ritual Murder in Medieval EuropeNo ratings yet

- Between Christ and Caliph: Law, Marriage, and Christian Community in Early IslamFrom EverandBetween Christ and Caliph: Law, Marriage, and Christian Community in Early IslamNo ratings yet

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam: New EditionDocument16 pagesThe Encyclopaedia of Islam: New EditionAhmed Said YalçınkayaNo ratings yet

- 21 Ways To Remove SinsDocument8 pages21 Ways To Remove SinsShahmeer KhanNo ratings yet

- Reform Movements: DeobandDocument14 pagesReform Movements: DeobandGhulam AliNo ratings yet

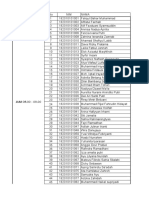

- Result Model TestDocument21 pagesResult Model TestatikNo ratings yet

- Template Nilai Portofolio-VI.A-Sejarah Kebudayaan IslamDocument60 pagesTemplate Nilai Portofolio-VI.A-Sejarah Kebudayaan IslamMHadiBasyaruddinNo ratings yet

- Eight ArticlesDocument17 pagesEight ArticlesMadni HanifNo ratings yet

- 2022 Gregorian CalendarDocument2 pages2022 Gregorian CalendarBibin K JohnNo ratings yet

- Senarai Nama Murid THN 6 2020 PDFDocument10 pagesSenarai Nama Murid THN 6 2020 PDFAni HaniNo ratings yet

- Sources of Law in Medieval India: National Law University and Judicial Academy, AssamDocument11 pagesSources of Law in Medieval India: National Law University and Judicial Academy, AssamUditanshu Misra100% (1)

- Islam and WomanDocument12 pagesIslam and WomanIftikharUlHassanNo ratings yet

- Handout of 1939-1940 Rule of Congress (Why Hated by Muslims)Document4 pagesHandout of 1939-1940 Rule of Congress (Why Hated by Muslims)mohammad baqarNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Swab TKD Sabtu TGL 3Document9 pagesJadwal Swab TKD Sabtu TGL 3admin rsgmNo ratings yet

- Abjad Table of Arabic Letters' Heavenly Values - Secrets of Muqatta'at - The Muhammadan WayDocument6 pagesAbjad Table of Arabic Letters' Heavenly Values - Secrets of Muqatta'at - The Muhammadan Waywarner50% (2)

- Absensi Pengambilan Rapor-1Document17 pagesAbsensi Pengambilan Rapor-1Elvi AsnikhaNo ratings yet

- Wushulul MaziyahDocument50 pagesWushulul MaziyahSyamsul MNo ratings yet

- Musnad Ahmed Ibn Hambal Vs Sahih BukhariDocument35 pagesMusnad Ahmed Ibn Hambal Vs Sahih BukhariRana Mazhar0% (1)

- Office of The Director Admissions PG Entrance 2023Document51 pagesOffice of The Director Admissions PG Entrance 2023Code CrackerNo ratings yet

- Dua Flash Card For KidsDocument5 pagesDua Flash Card For KidsAlmedinaĐonkoKaračićNo ratings yet

- En Surah An Nur PDFDocument88 pagesEn Surah An Nur PDFAmir NadeemNo ratings yet

- Battle of TaboukDocument4 pagesBattle of Taboukmatt malinskyNo ratings yet

- Should A Muslim Use Complementary Therapies: Halal or Haram?Document25 pagesShould A Muslim Use Complementary Therapies: Halal or Haram?RonaldNo ratings yet

- Al-Quran Juz 1Document28 pagesAl-Quran Juz 1Anang FathurahmanNo ratings yet

- Harf JarrDocument1 pageHarf JarrBishara SaitNo ratings yet

- Delhi Between Two Empires: Society, Government and Urban GrowthDocument20 pagesDelhi Between Two Empires: Society, Government and Urban GrowthIshitaNo ratings yet

- My Own Theory of Devolution (Jessica Zafra)Document5 pagesMy Own Theory of Devolution (Jessica Zafra)Joven Joseph LazaroNo ratings yet

- Peserta Pangandaran Tour 28 Nov 2023Document6 pagesPeserta Pangandaran Tour 28 Nov 2023Pelman SilabanNo ratings yet

- Challenges Faced During The Caliphate ofDocument3 pagesChallenges Faced During The Caliphate ofLatafat AliNo ratings yet

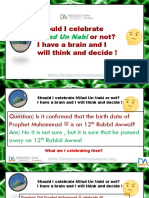

- Let Me Decide If I Want To Celebrate Milad or NotDocument10 pagesLet Me Decide If I Want To Celebrate Milad or NotFarehania MasoodNo ratings yet

- A Portrait of The Umayyad Islam Orginal PDFDocument318 pagesA Portrait of The Umayyad Islam Orginal PDFMuzik LeakerNo ratings yet