Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 15.207.31.38 On Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 15.207.31.38 On Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

Uploaded by

geosltdOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 15.207.31.38 On Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 15.207.31.38 On Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

Uploaded by

geosltdCopyright:

Available Formats

Education and Economic Development in Southeast Asia: Myths and Realities

Author(s): Anne Booth

Source: ASEAN Economic Bulletin , DECEMBER 1999, Vol. 16, No. 3, SOCIAL SECTORS IN

SOUTHEAST ASIA: Role of the State (DECEMBER 1999), pp. 290-306

Published by: ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25773594

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to ASEAN Economic Bulletin

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ASEAN Economic Bulletin Vol. 16, No. 3

Education and Economic

Development in

Southeast Asia

Myths and Realities

Anne Booth

The author refutes the arguments by many others including the World Bank that heavy

investments in education have led to equitable growth in several fast-growing economies of

Southeast Asia since the 1960s. The author does not think that the governments of these

countries have been especially astute at planning educational development in order to meet

the demands of the fast-changing labour market. This is because in several cases it is clear

that educational and skills bottlenecks have forced governments into relying on expatriate

labour, and in some cases retarded economic growth.

The literature on the "Asian Miracle" which The World Bank, in its well-known 1993 report,

proliferated in the early 1990s offered a range of was only slightly more circumspect in its claims.

explanations for the remarkable growth record of It was argued that "in nearly all the rapidly

the Asian "high performers" (or HPAEs as they growing East Asian economies, the growth and

have become known) but almost all the contri transformation of systems of education and

butions agreed on the importance of education. In training during the past three decades has been

their analysis of "the key to the Asian miracle", dramatic. The quantity of education children

Campos and Root (1996, p. 56), stressed that: received increased at the same time that the

quality of schooling, and of training in the home,

All of the HPAEs have invested heavily in

markedly improved" (World Bank 1993, p. 43).

education and, unlike many other developing

The report stressed that most of the HPAEs had

countries, have concentrated on primary and

secondary schooling. The share of the edu higher enrolment rates than would have been

cational budgets allocated by the HPAEs to basic predicted for their level of income from a sample

(primary and secondary) education is signi of over 90 developing economies. Only Thai

ficantly higher than the share allocated by other land's performance was singled out as "weak" in

developing countries. Tertiary education has comparison to the HPAE average. Other studies

been left largely to the private sector. originating from, or published by the World Bank,

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 290 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

have also stressed the improvements in both number of countries (especially Japan, South

quantity and quality of education in the HPAEs, Korea and Taiwan) have been assumed also to

where quality is measured by declines in hold in much of Southeast Asia, and frequently

repetition and dropout rates (Birdsall, Ross and China as well, often with only the most cursory

Sabot 1995, p. 481). These authors pointed to examination of the statistical record in these

the virtuous circle found in much of East Asia countries. Nowhere is this more true that in the

where education stimulates growth and growth discussion of education and its role in the growth

stimulates education. In addition, they claimed process. Because Taiwan and South Korea

that high rates of investment in education lowers undeniably "educated ahead of demand", even at

inequality, which in turn further stimulates both the risk of substantial educated unemployment,

economic growth and more investment in it is widely assumed that the fast growing eco

education. Furthermore, rapid growth in the nomies of Southeast Asia (Singapore, Malaysia,

HPAEs has speeded up the demographic transition Thailand and Indonesia) did the same.1 In fact

which has allowed governments to greatly it is very clear that the course of educational

increase the educational budget per student, development in these four countries has been very

thereby improving quality of instruction. different from that in Taiwan and South Korea.

There can be little doubt that these views have Partly this reflects very different colonial legacies,

now become orthodoxy, a canonical tradition but it also reflects very different government

which many writers on East Asia now follow policies towards the role of education in the

uncritically. Indeed it is now frequently asserted growth process in the post-independence era, both

in the literature on educational development that within Southeast Asia and between Southeast and

the Asian tigers have created a "new model", a Northeast Asia.

key component of which is "forging newer, closer The main purpose of this paper is to review

links between education, training, and economic these policies for Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand,

growth" (Ashton and Sung 1997, p. 207). In Indonesia and Vietnam. The first four countries

contrast with the mature industrial economies, were among the HPAEs whose record has been

especially the UK and the United States where the examined by the World Bank (1993), and by

educational system is claimed to have developed numerous other analysts as well. Vietnam is one

independently of the needs of the economy, it is of the Southeast Asian "transitional" economies

argued that in the so-called Asian Tigers, "the which has now largely abandoned central plan

relationship between education and economic ning and is moving towards market capitalism,

growth has been much stronger, with the edu with some important consequences for its edu

cational system and its output exhibiting a very cational sector. It has joined the Association of

strong and much closer linkage to the require Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and certainly

ments of the economy" (ibid., 207). Cummings views its more successful ASEAN partner eco

(1995, p. 67) goes so far as to argue that "the nomies as offering useful lessons for its own

Asian state in seeking to coordinate not only the development strategies. It will be argued below

development but also the utilisation of human that the accelerated economic growth which has

resources and involves itself in manpower occurred in Vietnam under transition has affected

planning and job placement and increasingly in the educational sector in ways which are not

the coordination of science and technology". entirely positive, and the Vietnamese Government

It is not the intention of this paper to argue that would be wise to learn from the mistakes of some

all these assertions are wrong for all the countries of its ASEAN partners before its education system

categorized by the World Bank as HPAEs, but deteriorates to a point which jeopardizes its future

rather to point out that much of the "Asian growth.

miracle" literature suffers from gross over Before examining country case studies, it is

generalization. Findings from a very small useful to look at the data on secondary and

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 291 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tertiary enrolments, and on educational expen Singapore

ditures for a group of Asian economies (Table 1).

Singapore is often considered, along with South

It is evident that there is no clear relationship

Korea and Taiwan, to exemplify the model of the

between per capita GDP and enrolments; although

densely populated, resource poor Asian economy

Singapore had a higher per capita GDP in 1992

than either South Korea or Taiwan, both secon

which achieves rapid and sustained economic

growth through heavy investment in education

dary and tertiary enrolments were lower. Thailand

and training. The Singapore Government over the

stands out as having a very low secondary enrol

years has done much to foster this image, and the

ment ratio for its level of income; lower than

official rhetoric about the Singapore model is

either Indonesia or China. Thailand, Malaysia,

replete with references to the importance of

and Indonesia all had lower secondary enrolments

in 1992 than Taiwan and South Korea had human resource development, and the pursuit of

excellence in education. But at the same time, key

achieved in 1980, although both Malaysia's and

government ministers have always been aware of

Thailand's per capita GDP in 1992 was higher

than that of South Korea in 1980.2 Vietnam stands the formidable challenges which education policy

in the island republic must confront. A govern

out as the only country to experience a fall in

ment report published in 1979 stated the key

secondary enrolment rates over the 1980s. There

problems as follows:

is also a wide variation in government expen

ditures as a proportion of GDP with Indonesia, Most school children are taught in two languages

China and Vietnam all having markedly lower ? English and Mandarin. 85% of them do not

ratios than the other countries in 1992. speak either of these languages at home. Our

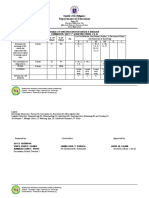

TABLE 1

Educational Indicators for Fast Growing Asian Economies, 1980-92

Country0 Gross secondary Tertiary students Government education

enrolment ratio per 100,000 people expenditures as % GDP

1980 1992 1980 1992 1980 1992

Singapore 58 68 963 3233* 3.1 4.4

Taiwan 80 96 2035 2604 3.6 5.6

South Korea 78 91 1698 4253 3.7 4.2

Malaysia 48 60 419 697 6.0 5.5

Thailand 29 39 1284 2029 3.4 4.0

Indonesia 29 43 367 1045 1.7 2.2

China 46 54 116 192 2.5 2.0

Vietnam 42 32 214 149 n.a. 2.1

a Ranked in order of per capita GDP, 1992

b Data refer to 1991

SOURCES: UNESCO World Education Report (1995), Tables 6, 8, 10; with additional data on Taiwan

from the Taiwan Statistical Yearbook (1995), Tables 47, 53 and Taiwan Statistical Data Book, various

issues.

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 292 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

system is largely modelled on the British pattern The report went on to emphasize that the decades

but the social and demographic background of the 1960s and 1970s had seen a steady decline

could hardly be more dissimilar. If, as a result of in numbers of children enrolled in the Chinese

a world calamity, children in England were stream schools in Singapore and an increase in

taught Russian and Mandarin, while they con

numbers enroled in schools where English was the

tinued to speak English at home, the British

medium of instruction. This reflected widespread

education system would run into some of the

problems which have been plaguing the schools

parental conviction that fluency in English was

in Singapore and the Ministry of Education (Goh crucial in gaining access to well paying jobs.

1979, p. 1-1).

TABLE 2

The Singapore Labour Force: Percentage Breakdown by

Educational Attainment, 1974, 1985, 1997

Total Male Female

1974

Nil/Below Primary 40.3 41.8 36.9

Primary/Post-primary 31.4 33.1 27.7

Secondary 19.7 16.4 26.8

Post Secondary 6.2 5.8 6.9

Tertiary 2.4 2.7 1.6

Others 0.1 0.2 0.1

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

1985

Nil/Below Primary 22.8 23.2 22.2

Primary/Post-primary 31.3 34.7 25.3

Secondary 29.3 25.5 36.0

Post Secondary 11.0 10.5 11.8

Tertiary 5.2 5.6 4.3

Others 0.4 0.4 0.4

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

1997

Primary/Below 24.8 25.9 23.1

Secondary 44.7 43.0 47.0

Post Secondary 11.6 10.6 13.1

Diploma 7.4 8.4 5.9

Degree 11.6 12.0 10.9

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

SOURCES: Yearbook of Labour Statistics 1976 (Singapore: Ministry of Labour);

Yearbook of Labour Statistics 1985 (Singapore: Ministry of Labour); Yearbook

of Manpower Statistics 1997 (Singapore: Ministry of Manpower).

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 293 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

However, many children from backgrounds where TABLE 3

English was not spoken faced enormous diffi Percentage Distribution of the Labour Force

culties in the English stream schools, difficulties by Educational Attainment

which were aggravated by teachers who were

themselves often inadequately trained and faced Male Female

large classes. Surveys carried out by the Ministry

of Defence in the mid-1970s found that, of those South Korea 1974

recruits who had been to English-medium schools No schooling 12.9 28.5

but who had not passed O levels, only 11 per cent Primary 41.0 49.9

had retained reasonable fluency in English. The Secondary 38.5 20.0

majority of students were not successful in College/University 7.6 1.6

passing O-level examinations. Some 65 per cent

of children entering first-year primary school did Total 100.0 100.0

not succeed in passing at least three O-levels, and

over one third did not pass the primary school Thailand 1981

leaving examination. Out of each cohort of one No schooling 5.6 10.4

thousand entering primary school in the early Primary 82.4 82.4

1970s only 137 succeeded in completing senior Secondary 8.3 4.2

high school; in Taiwan the comparable figure was College/University 3.8 2.9

514 while in Japan it was 926 (Goh 1979, Annex

3). Total 100.0 100.0

Of course it could be argued that in ethnically

homogeneous countries such as Taiwan and Japan Indonesia 1994

children progressed through a school system No schooling 7.5 16.4

where they were taught in the language they used Primary 59.6 59.9

at home, and where they did not have to grapple Secondary 29.7 21.1

with instruction in a foreign language. But the College/University 3.2 2.6

consequences of the Singapore system, with its

high failure and low continuation rates for the Total 100.0 100.0

skill level of the labour force were by the 1970s

already serious. In 1974, less than 30 per cent of SOURCES: South Korea: 1974 Special Labour Force

the labour force had completed secondary Survey Report (Seoul: Bureau of Statistics, Economic

schooling or a higher level; for males the Planning Board); Thailand: Report of the Labour Force

percentage was slightly lower (Table 2). This Survey Round 2 (Bangkok: National Statsitical Office);

Indonesia: Labour Force Situation in Indonesia 1994

could be compared with South Korea where in (Jakarta: Central Bureau of Statistics).

1974 well over 38 per cent of the male labour

force has completed secondary schooling (Table infrastructure development, including ambitious

3). In 1974 per capita GDP was over twice as high housing development schemes. But in addition,

in Singapore as in South Korea. Part of the education development was dominated by a

explanation for the poor educational level of the narrow preoccupation with manpower planning

Singapore labour force in the 1970s was the projections, underlying which was a fear of the

extremely limited access to education provided by politically destabilizing effects of unemployed

the colonial government. But since self high school and college graduates.3

government was achieved in 1959, the pace of The recommendations of the Goh report

educational expansion, especially at the post included a compulsory nine-year cycle for all

primary levels, was slow. Partly this reflected the children, and streaming of children so that the

government's preoccupation with physical groups of differing ability could be taught at a

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 294 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

pace which suited their abilities. But the govern be attributed to demographic change, low con

ment continued to be concerned about the state of tinuation rates were also to blame. A government

education, especially after the economy slowed report on future options for the economy pub

sharply in the mid-1980s. Enrolment growth over lished in 1986 stressed the continuing low level of

the 1970s at both the lower secondary and the education among the Singapore work-force; in

academic upper secondary levels was very slow 1979 it was still the case that 60 per cent had at

in comparison with most other parts of the region most completed primary school, and only three

(Table 4). Although part of this slow growth could per cent had tertiary qualifications (Republic of

TABLE 4

Annual Average Rates of Growth of Lower and Upper Secondary Enrolments,

1970-92

Country Lower Academic Vocational

Secondary Upper Upper Secondary

Secondary

1970-80 1980-92 1970-80 1980-92 1970-80 1980-92

Thailand 9.4 3.6 9.4 -0.3 n.a. 0.4

Malaysia 6.9 1.4 9.9 3.2 13.7 7.8

Singapore 0.8 0.8 5.3 6.6 5.4

Indonesia 9.8 4.0 (4.5) 11.0 6.7 (6.9) n.a. -5.4

Vietnam n.a. -0.5 n.a. -2.9 n.a. -5.4

China 7.1 -0.4 10.7 -0.4 35.5 6.3

Taiwan 3.0 0.8 -0.5 1.8 6.6 2.4

South Korea 5.8 -1.2 12.2 3.5 9.5 -0.1

Notes and Sources:

In most cases growth rates are estimated by fitting a semi-log function to the data. Unless

otherwise noted data refer to both government and private schools.

Thailand: Data from Bureau of Educational Policy and Planning, Ministry of Education. Estimates

refer to 1972-81 and 1981-93 respectively. For 1972-81 data refer to all secondary schools.

Malaysia: 1971-80: data from Mid-term Reviews of the Second, Third, Fourth Malaysia Plans.

There are gaps for some years which were filled by interpolation. 1980-92: data from Education

Statistics of Malaysia (annual publication, Ministry of Education, Educational Planning and

Resources Division).

Singapore: Data from Economic and Social Statistics of Singapore, 1960-82, Statistical Yearbooks

of Singapore, various issues. Up to 1980 data refer to all academic high schools; from 1981 to

1991 academic high schools and pre-university high schools are combined. Data for 1992 not

available.

Indonesia: Data from Lampiran Pidato Kenegaraan, various issues. They refer to government

schools only; religious and other private schools are omitted. Figures in brackets for 1980-92

refer to both government and private schools.

Vietnam: Data are from World Bank (1997), Table 2.3 and refer to 1984/5 to 1994/5.

China: Data from China Statistical Yearbook, various issues.

Taiwan: Data from Educational Statistics of the Republic of China, 1993.

South Korea: Education in Korea, various issues.

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 295 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Singapore 1986, p. 113). Attention was drawn to TABLE 5

the sharp disparities between Singaporean edu Distribution of the Labour Force by

cational achievement and that of Japan, the USA Educational Attainment

and Taiwan. An academic analysis of policy

options for the Singapore economy published in Male Female

1988 also drew attention to the failings of the

education system and argued that improving both Singapore 1974

the quality and quantity of educated people in the Below primary 41.8 36.9

Singapore work-force was "now an urgent task Primary 33.1 27.7

because there has been an underinvestment in Secondary 16.4 26.8

both formal and informal education" (Lim 1988, College/University 8.5 8.5

p. 167).

The Singapore Government was not slow to Total 100.0 100.0

grasp the lessons of these and other studies, and

educational opportunities have certainly expanded Malaysia 1988

in Singapore since the mid-1980s, especially at No formal education 7.0 18.7

the upper secondary, vocational and tertiary levels Primary 38.9 31.2

(Tables 4 and 5). In addition the rapid demo Secondary 49.1 45.3

graphic transition in the island republic has meant College/University 5.0 4.7

lower numbers of children coming into the school

system, especially over the 1980s, so more Total 100.0 100.0

resources can be spent per pupil. Yet secondary

enrolment rates by the early 1990s were still well Thailand 1993

below those in South Korea and Taiwan (Table 1), Below primary 5.6 8.7

and as late as 1997, almost 25 per cent of the Primary 72.2 74.8

labour force still had, at most, only completed Secondary 15.8 9.7

primary education (Table 2). In the mid-1990s, College/University 6.4 6.7

academic studies were still drawing attention to

the very low level of educational attainment in the Total 100.0 100.0

population compared with Western countries with

similar levels of per capita GDP (Chen 1996, Sources: Yearbook of Labour Statistics 1976 (Singa

pp. 84-85). Most workers with low educational pore: Ministry of Labour); Malaysia: The Labour Force

attainment were in low-paying jobs with limited Survey Report: Malaysia, 1987-1988 (Kuala Lumpur:

opportunity for job progression. Many were in the

Department of Statistics); Thailand: Report of

the Labour Force Survey 1993, Round 3: August

older age groups, and there are now fears that (Bangkok: National Statistical Office)

when they retire they will have inadequate

savings and pensions entitlements to finance their

old age. The implications of this for social in from the education system were absorbed in

equalities are examined further below. unskilled service sector jobs. Both the govern

It can of course be pointed out that Singapore's ment and academic analysts are now acutely

relatively weak educational achievement has not aware that this type of economic growth is not

stopped the economy growing very rapidly over sustainable, and that heavy investment in human

almost four decades. This is obviously true, but resource development will be crucial for Singa

in the early phase of Singapore's economic pore's future. But this awareness has developed

development, much of the industrial development slowly, many would argue far too slowly, in

was labour-intensive and demanded relatively response to changes in the labour market, and to a

unskilled workers.4 In addition many dropouts growing appreciation on the part of the authorities

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 296 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of the experience of other fast-growing Asian Malay primary graduate to continue to secondary

and tertiary education. The influential Razak

economies. It certainly cannot be argued that the

Singapore Government has led the market in Report of 1956 advocated universal primary

investing in the development of human resources. education and unification of the education system,

In that sense it has clearly played a very different with Malay/English bilingualism as the ultimate

role from governments in South Korea and goal (Snodgrass 1980, p. 245). Universal primary

Taiwan; indeed I will argue below that it has education was seen as the easier of these two

played a very different role from the government objectives, and considerable progress was made in

of its near neighbour, Malaysia. the 1960s; bilingualism required more resources

and was opposed by both Chinese and Indian

minorities. The result was that English remained

Malaysia

the medium of instruction in many secondary

Rudner (1994, p. 285) characterized British schools and in the universities, and in 1970 when

educational policy in the Federated Malay States the New Economic Policy was adopted, Malays

(FMS) as seeking "to strike a balance between the were still only a minority in higher education. A

provision of sufficient English schooling to satisfy crucial aim of the NEP was to sever the link

urban manpower and colonial administrative between ethnicity and post-primary education and

needs, while avoiding unwanted social changes make access to secondary schools and universities

among the local population". Both the British available to all on the basis of ability.

colonial authorities and the Malay aristocratic Affirmative action was needed to accelerate

elites were concerned that exposing the mass of Malay enrolments at upper secondary and tertiary

the Malay peasantry to English education would levels and after the 1969 riots, the government

make them discontent with their traditional rural made it clear that a number of measures would be

lifestyles, and encourage them to drift to the cities adopted to facilitate increased Malay progression

where they would inevitably form an economic through the education system. The most con

underclass. While urban schools catering largely troversial was the adoption of Malay language

for Chinese, Indian and Eurasian children instruction at all levels as this inevitably dis

expanded with both government and private criminated against non-Malays. The more affluent

finance, rural education for the Malays was sent their children abroad for secondary and

restricted to vernacular instruction designed to tertiary education; many non-Malays from less

make them better farmers and fishermen, more wealthy families found their progress blocked

aware of the world around them but still content both by the language requirements and by

with their rural way of life. Although enrolments stringent ethnic quotas. But enrolments of Malays

in Malay vernacular schools increased rapidly, by at the secondary and tertiary levels did increase

the late 1930s only about 20 per cent of eligible rapidly and by 1985, 68 per cent of upper

children were attending school; many parents secondary and 63 per cent of degree enrolments

could not see the point of education which did not were Malay, slightly higher figures than the

lead to social mobility (Rudner 1994, pp. 289-90; population share (Government of Malaysia 1989,

Snodgrass 1980, pp. 237^3). Table 13.2). Although rates of growth of enrol

When the Federation of Malaysia was formed ments at the lower and upper secondary levels

and granted full independence from Britain in slowed in the 1980s, compared with the rapid

1963, the educational legacy was thus highly growth of the 1970s, gross secondary enrolments

inequitable in terms of race and place of resid had reached 60 per cent in 1992, which was a

ence. Although in the post-war years, primary higher percentage than that attained by Singapore

schooling for Malays in the vernacular had greatly in 1980, although lower than Taiwan and South

expanded it remained very much second-class Korea in that year (Tables 1 and 4). Government

education, and it was often very difficult for a expenditures on education were over five per cent

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 297 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of GDP in 1992, a higher percentage than in most in educational achievement and changes in labour

other parts of Asia (Khoman 1993, p. 344).5 In force structure.

1988 when per capita GDP was still rather lower

than the level Singapore had attained in 1974, the Thailand

proportion of the labour force with at most

primary schooling was substantially lower Although Thailand was never colonized by a

(Table 5). For male workers the proportion with Western power, the Thai Government was slow

at most primary was lower than in South Korea in to expand access to education and in the early

1974 (Tables 3 and 5). The proportion of women years of the 20th century the vast majority of

in the labour force with at most primary education the population were illiterate (Feeny 1998,

was considerably higher than for men, but still Table 13.1). Universal primary education was

much lower than in Singapore in 1974 (Table 5). adopted as an ideal in the 1920s, and after the

A comparison of Malaysian educational pro 1932 revolution pursued with some vigour by the

gress from 1970 to 1990 with that of Singapore government, although little progress was made in

does not, in my view, support the rather simplistic rural areas (Phongpaichit and Baker 1995, p. 368).

argument that resource-rich countries such as But literacy rates did increase especially for

Malaysia neglect human resource development, males, who had access to some education in

and do not invest in education to the same extent monasteries, and by 1947 it was estimated that

as the resource poor countries.6 After 1970 the about two thirds of the male population and 40

Malaysian Government was determined to per cent of women were literate. After 1950

increase Malay enrolments in secondary and primary enrolments in the secular education

tertiary education, even if the economic rationale system increased rapidly, and by 1970, the great

for increased investment in education, especially majority of children in the 7-12 cohort were in

at the tertiary level, did not at the time appear school (Wilson 1983, Table V-2; World Bank

compelling.7 In fact over the boom years from the 1994, p. 217). But at the secondary level

mid-1980s to 1996, the Malaysian economy was enrolments were extremely low; there were

able to absorb almost all the educated people virtually no secondary schools outside Bangkok

which the greatly expanded secondary and tertiary and a few large provincial towns until the 1960s,

system turned out. Government expenditure on and even when provision expanded in the 1970s

education was consistently higher than in many and 1980s, "cost and location still made it difficult

other Asian countries until the mid-1990s. The for a villager to climb the educational pyramid

reasons for this emphasis on education could be any higher than the primary level" (Phongpaichit

found in the determination of the Malay and Baker 1995, p. 369). The rapid growth in

dominated ruling coalition to erase the sharp enrolments over the 1970s was almost entirely in

distinctions in educational attainment and urban areas. The effect on the educational

employment by ethnic group which were a legacy attainment of the labour force was obvious; in

of colonial policies and which remained a potent 1981, while only six per cent of the male labour

source of discontent for the Malay majority in the force and ten per cent of the female labour force

post-independence era. By the early 1990s, "the had had no formal education, only a meagre 12

identification of race or ethnicity with economic per cent (seven per cent for female workers) had

function or occupation and sectoral activity had post-primary education (Table 3). The contrast

been generally reduced", although not completely with South Korea in 1974 was stark (in 1981 Thai

eliminated (Gomez and Jomo 1997, p. 166). per capita GDP was about the same as in South

Indigenous Malays were still under-represented, Korea in 1974).

and Chinese over-represented, in administrative Over the 1980s, secondary enrolment growth

and managerial occupations in 1995, which fell sharply compared with the 1970s, and by the

demonstrates the lags that exist between changes latter part of the 1980s, access to education had

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 298 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

become a highly controversial issue in discussions schools) increased from 1.4 million in 1990 to 2.4

of public policy in Thailand. Academics and million in 1996, and by 1996 gross enrolment

independent think-tanks such as the TDRI rates increased to 66 per cent in 1996 (Table 6).

stressed the very low level of educational attain There has also been a rapid growth in upper

ment of the labour force not just in comparison secondary enrolments, so that by 1996 gross

with Taiwan and South Korea but also with enrolment rates were 40 per cent (Table 6). Of the

Thailand's poorer neighbours such as the total growth in upper secondary enrolments

Philippines and Indonesia (Myers and Sus between 1990 and 1996, 55 per cent was in the

sangkarn 1992, p. 14; Khoman 1993, pp. 329-30). academic stream and 45 per cent in the vocational

Cross-country regressions showed that Thailand stream. Although private schools account for a

was well below the trend line relating per capita greater proportion of enrolments at the upper

GDP to post-primary enrolments; in other words secondary level (about 23 per cent in 1996), much

enrolments were much lower than for other of the enrolment growth over the 1990s took place

countries at similar levels of per capita GDP. By in government schools.

the early 1990s there were growing signs that the The Thai experience in the 1990s certainly

poor level of education especially among new shows that determined public action can make a

entrants to the labour force, was creating serious difference to post-primary participation rates,

economic problems (Bello, Cunningham and Poh even over a relatively short space of time. When

1998, pp. 56-57). Employers in both the manu

facturing industry and the modern service sector

complained that new recruits had to be given

TABLE 6

substantial remedial training, especially in

numeracy and technical skills, before they could Secondary Enrolments in Thailand, 1983-96

operate modern equipment. In the increasingly (Thousands)

tight labour market of the early 1990s, workers

who had acquired basic skills were often poached Year Lower secondary Upper secondary

by rivals, making firms increasingly reluctant to

1983 1224 968

invest in on-the-job training. As a result of skill

1984 1305 944

shortages, industries which were being priced out

of markets for labour-intensive manufactures such

1985 1309 935

1986 1278 907

as garments and footwear found it difficult to

move into medium technology sectors, especially

1987 1217 (32.6) 893 (24.2)

for export. In 1996 after a decade of rapid growth,

1988 1221 (32.8) 862 (23.4)

exports hardly expanded at all (Warr 1998,

1989 1282 (34.4) 837 (22.7)

pp. 50-58).

1990 1394 (37.2) 834 (22.5)

However, the debates of the late 1980s and 1991 1570(41.4) 879 (23.6)

early 1990s did lead to a number of reforms.

1992 1772 (46.8) 945 (25.3)

By 1994 the Thai Government was committed

1993 1991 (53.4) 1056 (28.2)

to a compulsory nine-year cycle which meant

1994 2200(59.7) 1185 (31.5)

accelerated expenditures on teaching training and

1995 2362 (64.4) 1321 (35.3)

upgrading of school facilities. Certainly there can

1996 2445 (66.0) 1482 (40.2)

be little doubt that transition rates from primary

to secondary level have increased over the 1990s; NOTE: Figures in brackets refer to enrolments as a

percentage of the numbers of children in the relevant

the official data indicate that they jumped from 54

age cohorts.

per cent in 1990 to 90 per cent by 1996 (Kingdom

of, Thailand 1997, p. 118). Numbers in lower SOURCE: Bureau of Educational Policy and Planning,

secondary schools (almost entirely government Ministry of Education.

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 299 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the financial crisis hit Thailand in the latter part rapidly; indeed over the 1970s enrolments growth

of 1997, there was widespread fear that the in Indonesia at both the lower and the upper

repercussions on the education system would be secondary levels were among the fastest in Asia

severe; parents would be forced to remove (Table 4). By the latter part of the 1980s, the

children from school and at least some of the government was able to claim universal primary

gains of the earlier part of the decade would be education, and gross enrolment rates at the lower

lost. It is still too early to judge whether these secondary level of around 55 per cent (in 1987/

fears are justified, but some observers argue that 88). Gross enrolment rates at the upper secondary

in fact the crisis may have the opposite effect and level in 1987/88 were around 35 per cent

persuade many millions of parents that better (Government of Indonesia 1993, Chapter XVI).

education is essential if their children are to In quantitative terms the achievements of the

compete successfully in a much tougher labour 1970s and 1980s were certainly impressive, and

market. During the latter part of the 1980s and as in the case of Malaysia, do not confirm the

early 1990s, jobs for young school leavers were argument that resource-rich countries neglect

plentiful and there was little incentive for parents education. In fact, it was the increasing revenues

to keep children on to complete the secondary from petroleum exports which permitted the rapid

cycle when they could be working and earning. growth in education during the fifteen years from

But as jobs for unskilled youth in sectors such as 1974 to 1989. But by the early 1990s there was

construction and manufacturing become far much evidence of serious problems in the

scarcer, and the qualifications for entry into such Indonesian education sector. Over the fifth Five

jobs escalate, parents will have little option but to Year Plan (1989-94), numbers enrolled in both

keep children in school for longer. lower secondary and academic upper secondary

schools actually contracted, so that enrolment

Indonesia ratios were lower by 1993 than they had been in

the late 1980s (Booth 1994, Table 14). In addition,

Indonesia emerged into the post-independence era it was clear by 1990 that universal primary

with probably the poorest educational legacy of education had not been attained; in 1990 it was

any country in Southeast Asia. The Dutch had estimated officially that only about 90 per cent of

expanded vernacular schooling for the indigenous children between seven and twelve were attending

population in the inter-war years, but for many school. In more remote parts of the archipelago

children their only educational experience was in the percentage was much lower (Booth 1994,

an Islamic school where almost all the teaching pp. 26-36).

was religious. Access to secondary and tertiary The government reacted to the disappointing

education was extremely limited for indigenous figures of the early 1990s with a pledge to achieve

Indonesians (Booth 1998, pp. 268ff). In spite of universal education over a nine-year cycle by the

the efforts made in the early post-independence end of the second decade of the twenty-first

years to increase enrolments at all levels, by the century. Crude participation rates in the lower

late 1960s it was estimated that only about 50 per secondary system were to increase by steps until

cent of children between seven and twelve were they reached 87 per cent by 2004. This would

in primary schools and enrolments rates at the involve an expansion in numbers at the lower

post-primary level were much lower. It was only secondary level of close to two million students.

in the early 1970s when the oil boom led to To accommodate an increase of the magnitide it

greatly expanded government revenues that the was estimated that some 45,000 new classrooms

government increased the allocation of resources would be needed, and tens of thousands of new

to the educational sector. From the early 1970s to teachers would have to be recruited and trained.

the latter part of the 1980s, enrolments at both the Unfortunately the Soeharto government in its final

primary and the secondary levels increased phase proved unwilling to increase budgetary

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 300 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

expenditures on education; in fact, they had fallen ages of 20 and 30 with tertiary qualifications was

somewhat as a percentage of GDP since the early very high (Manning and Junankar 1998, pp. 60

1980s, and by 1992 were just over two per cent of 61). This was in part attributed to rather rigid and

GDP, a very low proportion in comparison with inflexible markets for white collar workers; once

many other Asian countries (Table 1). Although people find such jobs they tend to stick in them.

gross enrolment rates did increase between 1993 But in addition there was much criticism from the

and 1997 at both the lower and upper secondary employer side that the quality of university

levels, by 1997/98 it was estimated that only graduates in Indonesia was extremely poor and

about 45 per cent of youths aged between 13 and that most of them required months or even years

15 were in lower secondary education (Govern of on the job training before they could contri

ment of Indonesia 1998, Table XVIII-3). bute much to output. In addition as the labour

As in Thailand, there was much evidence that market for particular categories of skilled worker

in Indonesia in the early 1990s many parents tightened, there was evidence of increased poach

either could not afford the paid-out costs of ing which made employers reluctant to invest in

keeping a child in secondary education, or if they long period of OJT (on-the-job training).

could, they were unwilling to incur the expen Given the severity of the economic turn-down

diture because they did not see the benefits in in Indonesia in 1998/99, the problem of un

terms of entry into better remunerated or more employment among young upper secondary and

prestigious occupations.8 Many young people with tertiary graduates is likely to worsen. Whether this

completed primary education were able to find will lead to falling enrolments is far from clear; as

employment in jobs such as construction and in Thailand many parents may be prepared to

manufacturing, and staying on to complete the spend more on education in order to secure their

lower, or even upper, secondary cycle did not progeny at least a place in the queue for "good

necessarily mean that they would be able to get jobs". In the longer run, quality at the higher

more highly prized jobs as white collar workers. levels can only be improved if quality at the lower

But at the same time, social rates of return levels is improved, and this can only come about

estimates for Indonesia indicated that investment if the government is prepared to invest more in

in lower secondary education yielded high returns both expanding participation and in improving

(14 per cent in 1989), and indeed some experts quality of instruction at the primary and lower

were arguing that the government was under secondary levels. There is abundant evidence to

investing in education and devoting a dispro suggest that while the quantitative expansion of

portionate share of the government investment education in Indonesia between the late 1960s and

budget to physical infrastructure (MacMahon and the late 1980s was impressive, quality remains

Boediono 1992, Table 7; Boediono 1994). poor at all levels.9 A sustained improvement in

Numbers in higher education in Indonesia have quality can only be achieved with a much greater

been growing rapidly since the 1980s, with much commitment of government funding.

of the expansion coming from enrolments in

private institutions. There has been much criticism Vietnam

that this expansion has been at the expense of

quality and that many of the private universities In French Indochina, even more than in most

are simply low quality diploma mills, catering to other parts of Southeast Asia in the era of

the demand for paper qualifications so that European colonialism, only a very small number

of children were given access to post-primary

graduates can get at least a place in the queue for

white collar employment. The evidence from education in the language of the colonial power

labour force surveys shows that, even before the (Furnivall 1943, p. 111). After the country was

financial crisis of 1997/98, unemployment rates partitioned in 1954, the northern economy was

for men and women in urban areas between the centrally planned, with a minimal role for the

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 301 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

market in allocating resources. This model was children on the farm (Booth 1997, pp. 245^7).

imposed on the south after reunification in 1975, The 1989 census data for Vietnam indicated

with at best partial success and by the mid-1980s that 48.5 per cent of the labour force in Vietnam

the government, motivated in part by the Chinese had either no education or at most incomplete

example, decided to abandon central planning and primary schooling. A further 28.7 per cent had

move towards a market economy while at the completed primary and only 23 per cent second

same time opening the economy to foreign ary or above. Even this level of education was

investment and to greater participation in inter greater than would be expected given the low per

national trade. capita GDP. If we compare the Vietnamese data

In 1980, after reunification but before the with those from Thailand in 1990 we see that an

implementation of market reforms, primary and even lower proportion of the Thai labour force

secondary enrolments were very high in Vietnam, had more than primary education, although a

indeed amazingly high given the country's low much greater proportion had completed primary

per capita GDP. At the primary level, 95 per cent school (Booth 1997, Table 6). In 1990 per capita

of children aged between seven and twelve were GDP in Thailand was several times that of

in primary school, a higher ratio than for example Vietnam. But at the same time it was clear that by

Brunei, although per capita income was vastly the early 1990s the Vietnamese education system

higher there (UNESCO 1996, p. 132). At the was under enormous strain and massive resources

secondary level, gross enrolment ratios were would be required to improve both the quantity

considerably higher than in Indonesia or Thailand and the quality of its output. Greater reliance on

(Table 1). These data of course may well have private sources of finance at the secondary and

been overstated, and it does seem clear that in tertiary level will probably be inevitable, although

the latter part of the 1980s and early 1990s, this may contravene deeply cherished notions of

enrolments at the lower and upper secondary social justice.

levels declined in absolute terms (Table 4; see

also World Bank 1997, p. 14). Given that numbers

Concluding Comments

of children in school age groups were growing

rapidly, the enrolment ratios fell very sharply at The main purpose of this paper has been to argue

the secondary level (Table 1). Why did this that the four "HPAEs" (highly performing Asian

happen? Certainly the economic restructuring economies) in Southeast Asia have all followed

which began in the mid-1980s under the rubric different education policies over the decades of

doi moi (renovation) did lead to increases in costs rapid growth since the 1960s, reflecting in part

of school attendance, while at the same time many their different colonial legacies, and in part the

teachers, especially those with degrees in foreign different attitudes of their governments to the role

languages, maths and science found that they of education in the growth process. Although both

could get far more lucrative employment in the the Taiwanese and South Korean experiences have

burgeoning private sector. In addition many been influential in Southeast Asia, as in other

teachers were forced into moonlighting in other parts of the world, there is little evidence that

occupations to supplement inadequate official educational development in Indonesia, Thailand,

salaries (Fforde and de Vylder 1996, pp. 230-33). Malaysia and Singapore has followed either the

As in other parts of the region, parents saw little Taiwanese or the South Korean path. Certainly the

point in making a financial sacrifice to keep their experience of these two countries has been much

children in poorly staffed and equipped secondary cited, especially by educational reformers, but

schools when the rewards in terms of access to usually in order to point out the lower level of

better jobs appeared so uncertain.10 In addition the educational attainment prevailing in, for example

return to family farming meant that most rural Singapore or Thailand compared with either

households needed the labour of their teenage South Korea or Taiwan. Several countries in

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 302 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Southeast Asia have experienced periods of favourable, and that this is in large part due to

stagnant or falling enrolments at the secondary their human resource development strategy. There

level and often these periods have coincided with is again often a tendency to generalize the ex

rapid economic growth and rapid growth in the perience of Taiwan and South Korea to other parts

demand for labour. There is plenty of evidence of the East Asian region with scant regard for the

that at the secondary level parents weigh up the facts. Elsewhere (Booth 1999, pp. 315-16) I have

costs and benefits of continuing education very pointed out that the available evidence shows that

carefully and often decide against keeping child the distribution of income in several fast-growing

ren in school beyond the primary level. Southeast Asian countries is not especially

Some critics of education policy in Southeast egalitarian, and indeed government policies which

Asia have argued that the real reason for poor in effect restricted access to secondary and tertiary

performance has been the heavy reliance on education have aggravated inequalities. The case

foreign companies, especially in the export of Singapore is especially instructive. Rao (1996,

oriented manufacturing sectors. Anderson (1998, Table 18.2) has demonstrated that the Gini

p. 306) points out that most foreign investors were coefficient of personal income accruing to

looking for low-wage export platforms, with resident taxpayers in Singapore has increased

"submissive and non-unionised workers" and somewhat between 1970 and the early 1990s, by

"such investors rarely had the interest or the which time it was 0.47 indicating a fairly skewed

resources to engage in vocational training outside distribution. Rao attributed at least part of the

the immediate needs of their businesses". There is increase in earnings inequality to the growth in

certainly some truth in this accusation, but it does demand for skilled workers with tertiary quali

not explain the very different policies pursued in, fications over the 1980s and 1990s, especially in

for example Malaysia and Thailand between 1970 sectors such as finance. Given the small number

and 1990. Both were successful in attracting of citizens with the appropriate qualifications

foreign investors into the export sector, but and the government's reluctance to grant large

educational policies and outcomes were very numbers of work permits to foreigners, the

different. In my view the key problem in those inevitable result was an increase in incomes for

countries where performance has been poor lies these workers, while at the bottom end of the

with governments, and their reluctance to use labour market, demand fell and wages stagnated,

budgetary resources to increase access to edu as the many labour-intensive industries moved

cation, especially at the secondary level. The case off-shore.

of Thailand in the 1990s demonstrates what can Rao cautioned against any simplistic expect

be achieved when governments decide to commit ation that an increase in educational attainment

more resources to the expansion of secondary will necessarily modify earnings inequality in

facilities especially in rural areas. But Thailand Singapore; he argued that many of the best

was forced into a policy change only after it educated workers are absorbed into the service

became very clear that severe skill shortages were sector where the distribution of earnings tends

emerging which were adversely affecting the to be more skewed. The sharp slowdown in

economy's ability to upgrade industrial tech economic growth in the wake of the financial

nology and move into the export of higher crisis has certainly led to reduced salaries in the

value-added products. Certainly neither Thailand financial sector, both in Singapore and in other

nor Singapore educated "ahead of demand" in the affected countries, but this effect on the distri

way that South Korea and Taiwan did. bution of earnings may only be temporary, and

A further point concerns the impact of South indeed could be offset by reduced earnings

east Asian educational strategies on equity. Many (through job losses) for less affluent households.

writers have argued that the equity outcomes of In other parts of Southeast Asia, such as Thailand

rapid growth in the HPAEs have been unusually and Indonesia, attempts by government to

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 303 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

increase educational enrolments at the secondary But that will involve a sharp increase in govern

level could aggravate existing income inequalities ment educational expenditures relative to GDP,

as those households who benefit from the especially in Indonesia.

increased expenditure will probably not come To return to the quotations with which I started,

from the bottom deciles of the income dis the argument that heavy investments in education

tribution.11 The very poor will be increasingly have led to equitable economic growth in several

marginalised in the race for better jobs and higher of the fast-growing economies of Southeast Asia

incomes. since the 1960s seems to me to be for the most

Given that in most parts of Southeast Asia part unconvincing and unsupported by the

enrolments in the higher levels of education evidence. Neither do I think that their govern

increase sharply in the upper income groups, and ments have been especially astute at planning

given the evidence of a tight link between level of educational development in order to meet the

education and lifetime earnings, there can be little demands of a fast-changing labour market. Indeed

doubt that restricted access to higher education is in several cases it is very clear that educational

a powerful reason for the transmission of relative and skills bottlenecks have forced governments

deprivation across generations (Khoman 1993, into relying on expatriate labour, and in some

p. 330) has argued for Thailand that "this inter cases retarded economic growth. It may well be

generational perpetuation of inequality is likely to that the mistakes committed by Southeast Asian

accelerate in future as production technology governments in the education sector have been

becomes increasingly more complex and employ less heinous than in many other countries. But this

ment shifts increasingly out of agriculture and is surely not the point. Mistakes have been made

into industry". Certainly the successful imple in several countries which the World Bank held

mentation of the nine-year cycle in both Thailand up as models, and the consequences of these

and Indonesia could potentially be a vehicle for mistakes for both growth and equity have not

greater equality, especially if at the same time a been trivial. Governments both in Southeast Asia

generous scholarship programme is available to and beyond should learn from these mistakes, and

permit bright children from less affluent homes take these lessons into account in fashioning

progress to upper secondary and tertiary levels. future educational policies.

NOTES

1. Ahuja, Bidani, Ferreira and Walton (1997, p. 53) argue that "in most East Asian economies educational

expansion took place ahead of demand, delivering new cohorts of appropriately skilled workers for each phase

of industrialisation". I would argue that in several Southeast Asian economies the process has been far from

smooth; the Philippines has had to export its large surplus of skilled and semi-skilled workers while Thailand

and Indonesia suffered from skills shortages in the early 1990s.

2. Behrmann and Schneider (1994, p. 21) stress that per capita income does not appear to be closely correlated

with enrolment rates and years of schooling for a cross-section of Asian countries in 1965 and 1987. They also

point out that the seven Asian economies with high growth rates "as a group do not appear to have had

unusually great schooling investments, although some individual countries within this group did have

relatively high enrolment rates at some school levels".

3. Goh (1977, Chapter 11) discusses the problems of implementing manpower planning in Singapore with

characteristic candour; however, he stresses the importance of this type of planning for Singapore's economic

future.

4. Huff (1995, p. 740) quotes Dr Goh Keng Swee's comment made in 1970 that "the electronic components we

make in Singapore probably require less skill than that required by barbers or cooks, consisting mostly of

repetitive manual operations".

5. Government educational expenditures have exceeded five per cent of GNP in Malaysia for every year since

1971; in the mid-1980s they were over six per cent of GNP.

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 304 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6. See for example Ashton and Green (1998).

7. A study carried out in the early 1970s argued that social returns to tertiary education expenditures were quite

low, and that the Malaysian Government was probably over-investing in education across the board (Hoerr

1973, p. 302). There is no evidence that the Malaysian Government took such warnings seriously, which was

just as well as the analysis on which they were based was certainly flawed.

8. Survey data indicated that in Indonesia in 1992, paid out costs of lower secondary education amounted to

almost 22 per cent of average annual per capita household expenditures. The comparative data assembled by

Tan and Mingat (1992, p. 190) show that 27 per cent of operating costs in public secondary education in

Indonesia in the mid-1980s were covered by fees, a higher ratio than elsewhere in East Asia except for South

Korea.

9. International comparative tests suggest that achievement of 9-10 year-olds in Indonesian schools is below the

international mean (World Bank 1997, p. 120).

10. Fforde and de Vylder (1996, p. 232) argue that by the early 1990s "it was no longer true that education in

Vietnam was free". As in Indonesia, by the early 1990s, paid out costs of education at the lower secondary

level amounted to a considerable proportion of average per capita household consumption expenditures in

Vietnam (Booth 1997, Table 8).

11. See Ahuja, Bidani, Ferreira and Walton (1997), Table 2.5 for data on the distribution of enrolment rates across

income groups. In Indonesia and Vietnam, the differences at the primary level are not great but they become

far more pronounced at the higher secondary and post-secondary levels.

REFERENCES

Ahuja, Vinod, Benu Bidani, Francisco Ferreira and Michael Walton. Everyone's Miracle? Revisiting Poverty and

Inequality in East Asia. Washington: World Bank, 1997.

Anderson, Benedict. The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia and The World, London: Verso,

1988.

Ashton, D. and J. Sung. "Education, skill formation and economic development: the Singaporean approach". In

Education: Culture, Economy and Society, edited by A. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown and A. Wells. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1997.

Ashton, David and Francis Green. "The Evolution of Education and Training Strategies in Singapore, Taiwan and

South Korea: A Development Model of Skill Formation". Paper presented to the ESRC Pacific Asia

Programme Conference, "Recovery and Beyond in Pacific Asia". London: Foreign and Commonwealth Office,

November, 1998.

Behrman, Jere R. and Ryan Schneider. "An International Perspective on Schooling Investments in the Last Quarter

Century in Some Fast-Growing East and Southeast Asian Countries". Asian Development Review 12, no. 2:

1-50.

Bello, Walden, Shea Cunningham and Li Kheng Po. A Siamese Tragedy. London: Zed Books, 1998.

Birdsall, Nancy, David Ross and Richard Sabot. "Inequality and Growth Reconsidered: Lessons from East Asia".

World Bank Economic Review 9, no. 3 (1995): 477-508.

Boediono, "Pendidikan, Perubahan Struktural dan Investasi di Indonesia". Prisma 1994 XXIII, no. 5 (May 1994):

21-38.

Booth, Anne. "Repelita VI and the Second Long-term Development Plan". Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

30, no. 3 (December 1994): 3^0.

-. "Vietnam and ASEAN: How Far Apart?" In Vietnam: Reform and Transformation, edited by

B. Beckman, Eva Hansson and Lisa Roman. Stockholm: Centre for Pacific Asia Studies, 1997.

-, Anne. The Indonesian Economy in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A History of Missed Opportunities.

London: Macmillan, 1998.

-. "Initial Conditions and Miraculous Growth: Why is South East Asia Different from Taiwan and South Korea?"

World Development 27, no. 2 (February 1999): 301-22.

Campos, J.E. and H.J. Root. The Key to the Asian Miracle: Making Shared Growth Credible. Washington: Brookings

Institution, 1996.

Chen, Geraldine. "The Graduate and Skills Labour Markets: Dimensions of Manpower Management". In Economic

Policy Management in Singapore, edited by Lim Chong-Yah. Singapore: Addison-Wesley Publishing

Company, 1996.

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 305 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cummings, William K. "The Asian Human Resource Approach in Global Perspective". Oxford Review of Education

21, no, 1 (1995): 67-81.

Feeny, David. "Thailand versus Japan: Why was Japan First?" In The Institutional Foundations of East Asian

Development, edited by Y. Hayami and M. Aoki. London: Macmillan, 1998.

Fforde, Adam and Stefan de Vylder. From Plan to Market: The Economic Transition in Vietnam. Boulder: Westview

Press, 1996.

Furnivall, J.S. Educational Progress in Southeast Asia. New York: Institute of Pacific Relations, 1943.

Goh, Keng-Swee. The Practice of Economic Growth. Singapore: Federal Publications, 1977.

-. Report on the Ministry of Education 1978. Singapore: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 1979.

Gomez, Edmund Terence and Jomo K.S. Malaysia's Political Economy: Politics, Patronage and Profits. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Government of Indonesia. Lampiran Pidato Pertanggungjawaban Presiden/Mandataris MPR Republik Indonesia,

1 Maret 1993. Jakarta: Department of Information, 1993.

-. Lampiran Pidato Kenegaraan Presiden Republik Indonesia, 15 Augustus 1998. Jakarta: Department of

Information, 1998.

Government of Malaysia. Mid-term Review of the Fifth Malaysia Plan 1986-1990. Kuala Lumpur: National Printing

Department, 1989.

Hoerr, O.D. "Education, Income and Equity in Malaysia". Economic Development and Cultural Change 21, no. 2

(January 1973).

Huff, W.G. "What is the Singapore Model of Economic Development?" Cambridge Journal of Economics 19 (1995):

735-59.

Kingdom of Thailand. Education in Thailand 1997. Bangkok: Office of the National Education Commission, Office

of the Prime Minister, 1997.

Khoman, Sirilaksana. "Education Policy". In The Thai Economy in Transition, edited by Peter Warr. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Lim, Chong-Yah et al. Policy Options for the Singapore Economy. Singapore: McGraw-Hill, 1988.

MacMahon, Walter W. and Boediono. "Universal Basic Education: An Overall Strategy of Investment Priorities for

Economic Growth". Economics of Education Review 11, no. 2 (1992): 137-51.

Manning, Chris and P.N. Junankar. "Choosy Youth or Unwanted Youth? A Survey of Unemployment". Bulletin of

Indonesian Economic Studies 34, no. 1 (April 1998): 55-93.

Myers, Charles and Chalongphob Sussangkarn. Educational Options for the Future of Thailand. Bangkok: Thai

Development Research Institute, 1992.

Phongpaichit, Pasuk and Chris Baker. Thailand: Economy and Politics. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press,

1995.

Rao, V.V. Bhanoji. "Income Distribution in Singapore: Facts and Policies". In Economic Policy Management in

Singapore, edited by Lim Chong-Yah. Singapore: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Republic of Singapore. The Singapore Economy: New Directions, Report of the Economic Committee. Singapore:

Ministry of Trade and Industry, February 1986.

Rudner, Martin. "Colonial Education Policy and Manpower Underdevelopment in British Malaya". In Malaysian

Development: A Retrospective. Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1994.

Snodgrass, Donald R. Inequality and Economic Development in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press,

1980.

Tan, Jee-Peng and Alain Mingat. Education in Asia: A Comparative Study of Cost and Financing. Washington:

World Bank, 1992.

UNESCO. World Education Report 1995. Oxford: Unesco Publishing, 1996.

Wilson, CM. Thailand: A Handbook of Historical Statistics, Boston: G.K. Hall and Co, 1983.

Warr, Peter G. "Thailand". In East Asia in Crisis: From Being a Miracle to Needing One, edited by Ross McLeod

and Ross Garnaut. London: Routledge, 1998.

World Bank. The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. Washington: The World Bank, 1993.

-. World Development Report 1994. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank, 1994.

-. Vietnam: Education Financing. Washington: World Bank, 1997.

Anne Booth is Professor, Department of Economics, School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 306 December 1999

This content downloaded from

15.207.31.38 on Sun, 04 Jul 2021 15:16:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- GAD Project ProposalDocument2 pagesGAD Project ProposalFelix M. Cabusor94% (34)

- Mixed Add Subtract Word Problems One v1Document2 pagesMixed Add Subtract Word Problems One v1ranj19869No ratings yet

- CertificateDocument5 pagesCertificateJunmar CaboverdeNo ratings yet

- 2016 - 2) Defining Higher Education Issues and Challenges in Southeast AsiaASEAN Within The International ContextDocument26 pages2016 - 2) Defining Higher Education Issues and Challenges in Southeast AsiaASEAN Within The International Contextravino69No ratings yet

- Peraturan EdukasiDocument4 pagesPeraturan EdukasiBimaNo ratings yet

- Regionalism and The Global Village: The Case of ASEAN IntegrationDocument18 pagesRegionalism and The Global Village: The Case of ASEAN Integrationpraise torreNo ratings yet

- Enquête Sur Les Relations Entre L'éducation Et La Croissance Et Leurs Implications Pour Les Pays en Développement D'asieDocument33 pagesEnquête Sur Les Relations Entre L'éducation Et La Croissance Et Leurs Implications Pour Les Pays en Développement D'asieAbderrazak OualiNo ratings yet

- Economic DevelopmentDocument100 pagesEconomic DevelopmentAJNo ratings yet

- Development Impacts of Globalization and Education: Evidence From The Asia-Pacific CountriesDocument20 pagesDevelopment Impacts of Globalization and Education: Evidence From The Asia-Pacific CountriesSmritiNo ratings yet

- Asean Dropout RateDocument8 pagesAsean Dropout RateRolando ArañezNo ratings yet

- CharterDocument27 pagesCharterSutar diNo ratings yet

- Education and Economic Growth in Pakistan A Coiintegration and Casual AnalysisDocument15 pagesEducation and Economic Growth in Pakistan A Coiintegration and Casual AnalysisssrassrNo ratings yet

- Study On Impact of Pandemic On Filipino Men and WomenDocument19 pagesStudy On Impact of Pandemic On Filipino Men and WomenMIBARRA, Robert Allen M.No ratings yet

- I S: U Xxi: J BGTDocument50 pagesI S: U Xxi: J BGTDin Aswan RitongaNo ratings yet

- Education, Poverty and Economic Growth in South Asia: A Panel Data AnalysisDocument24 pagesEducation, Poverty and Economic Growth in South Asia: A Panel Data AnalysisWahyu Eko IrfantoNo ratings yet

- Higher Education 2010 Confucian Model MarginsonDocument25 pagesHigher Education 2010 Confucian Model MarginsonLan Chi ĐỗNo ratings yet

- The Role of Higher Education in The Ethi PDFDocument24 pagesThe Role of Higher Education in The Ethi PDFMohammed Demssie MohammedNo ratings yet

- John Richards, Manzoor Ahmed, Md. Shahidul Islam - The Political Economy of Education in South Asia - Fighting Poverty, Inequality, and Exclusion (2021, University of Toronto Press) - Libgen - LiDocument256 pagesJohn Richards, Manzoor Ahmed, Md. Shahidul Islam - The Political Economy of Education in South Asia - Fighting Poverty, Inequality, and Exclusion (2021, University of Toronto Press) - Libgen - LiKomol PalmaNo ratings yet

- Charles 2010Document20 pagesCharles 2010Cristina CNo ratings yet

- Success and Education in South KoreaDocument27 pagesSuccess and Education in South KoreaCHEN VOON YEENo ratings yet

- EconDev LecNotesDocument37 pagesEconDev LecNotesSandaraNo ratings yet

- HE in SEA - FINAL - CompressedDocument65 pagesHE in SEA - FINAL - CompressedCharmielyn SyNo ratings yet

- Gender 3Document12 pagesGender 3Song HàNo ratings yet

- Park 2002 East Asian Model of Economic DevtDocument25 pagesPark 2002 East Asian Model of Economic DevtRobbie PalceNo ratings yet

- Article Financing in HEDocument17 pagesArticle Financing in HEbanazsbNo ratings yet

- 98-Article Text-239-1-10-20220321Document11 pages98-Article Text-239-1-10-20220321Klienwin Dave OlivianoNo ratings yet

- Human Capital Accum in Emerging Asia To 2030Document34 pagesHuman Capital Accum in Emerging Asia To 2030BillyWhizNo ratings yet

- DT TermpaperDocument8 pagesDT TermpaperSakif WaseeNo ratings yet

- EconDev LecNotesDocument63 pagesEconDev LecNotesSandaraNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Socio-Economic Benefits of Education in Developing Countries: A Example of PakistanDocument18 pagesAnalysis of Socio-Economic Benefits of Education in Developing Countries: A Example of PakistanBaloch 15No ratings yet

- Group Assignment I EditedDocument42 pagesGroup Assignment I EditedbojaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 110.93.80.98 On Sat, 18 Dec 2021 23:35:04 UTCDocument39 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 110.93.80.98 On Sat, 18 Dec 2021 23:35:04 UTCRaniel R BillonesNo ratings yet

- The Evolving Role of Higher Education in National Development Plans in Cameroon Focus On The Period 2000 2030 SR22509185326Document10 pagesThe Evolving Role of Higher Education in National Development Plans in Cameroon Focus On The Period 2000 2030 SR22509185326KadriNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument7 pages1 PB PDFSolomon Kebede MenzaNo ratings yet

- Paying For Education: How The World Bank and The International Monetary Fund Influence Education in Developing CountriesDocument55 pagesPaying For Education: How The World Bank and The International Monetary Fund Influence Education in Developing CountriesRaju PatelNo ratings yet

- Journal of Management Education-2008-Napier-792-819 PDFDocument30 pagesJournal of Management Education-2008-Napier-792-819 PDFsatishiitrNo ratings yet

- 1.3. Tzannatos Z. & Johnes G. - Training and Skills Development in The NICDocument24 pages1.3. Tzannatos Z. & Johnes G. - Training and Skills Development in The NICArcticpaulaNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Economic Transition) Khoo, Boo Teik - Southeast Asia Beyond Crises and Traps - Economic Growth and Upgrading (2017, Palgrave Macmillan)Document322 pages(Studies in Economic Transition) Khoo, Boo Teik - Southeast Asia Beyond Crises and Traps - Economic Growth and Upgrading (2017, Palgrave Macmillan)Pinoy MindanaonNo ratings yet

- EJC37488Document14 pagesEJC37488RemelynNo ratings yet

- Education and National Development in Asia: Trends and IssuesDocument20 pagesEducation and National Development in Asia: Trends and IssuesGood HeartNo ratings yet

- Role of Education in Human Development - A Study of South Asian CoDocument14 pagesRole of Education in Human Development - A Study of South Asian CoImran ImamNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Women Education On Economic Developmentin EthiopiaDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Women Education On Economic Developmentin EthiopiaYonatan ZelieNo ratings yet

- Abuza PoliticsEducationalDiplomacy 1996Document15 pagesAbuza PoliticsEducationalDiplomacy 1996Thy LeNo ratings yet

- Perera2018 SBCDocument10 pagesPerera2018 SBCNany Suhaila Bt ZolkeflyNo ratings yet

- 1 Muhammed HaronDocument14 pages1 Muhammed HaronmiroswatNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTD.: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument34 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTD.: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPRocio NuñezNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press Comparative and International Education SocietyDocument21 pagesThe University of Chicago Press Comparative and International Education SocietyPanayiota CharalambousNo ratings yet

- Cost Analysis For Ed PolicymakingDocument51 pagesCost Analysis For Ed PolicymakingAparajitaRoyNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument7 pagesPDFKhansa AttaNo ratings yet

- Jomo DEVELOPMENTAL STATESDocument21 pagesJomo DEVELOPMENTAL STATESrbcalcioNo ratings yet

- Development of Regions, Industries and Types of Economic ActivityDocument11 pagesDevelopment of Regions, Industries and Types of Economic Activityassignment helpNo ratings yet

- Global Development InstituteDocument35 pagesGlobal Development InstituteAfifNo ratings yet

- Senior Seminar 7Document22 pagesSenior Seminar 7Yonatan ZelieNo ratings yet