Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Miners Welfare The Seventies

Uploaded by

Catharsis HaddoukOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Miners Welfare The Seventies

Uploaded by

Catharsis HaddoukCopyright:

Available Formats

The Miners' Welfare Commission and Pithead Baths in Scotland

Author(s): GEORGINA ALLISON

Source: Twentieth Century Architecture , SUMMER 1994, No. 1, INDUSTRIAL

ARCHITECTURE (SUMMER 1994), pp. 55-64

Published by: The Twentieth Century Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/41859420

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Twentieth Century

Architecture

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Pithead

è The and Miners' Pithead BathsBaths

Welfarein ScotlandScotland

in Commission

GEORGINA ALLISON

55

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

56

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

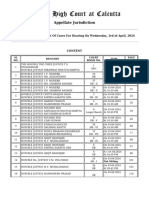

THE MINERS' WELFARE

COMMISSION

OURING approximately eighty pithead baths in Scotland,1 and about twice that

OURING numbernumber

approximately in the England

in England period eighty

and Wales. and 1919-1939,

The vast majoritypithead Wales. Thewerebathsexecuted

of these the vast Miners'

in in majority Scotland,1 Welfare of these and Commission about were executed twice built that in

what would become the International Style of the thirties, and their planning re-

vised the few available precedents into a design that was efficient in time, mate-

rials, and cost. Two of them, Polkemmet in Lothian and Betteshanger in Kent,

were included in the 1939 Architects' Journal poll2 of the most popular modern

buildings, and many were included in the Pevsner guides to the Buildings of

England.3 i For a full list of confirmed Scottish

pithead baths refer to appendix B.

Thus these buildings are of prime historical importance. Not only are they,

2 Polkemmet was nominated by the writer

as individual buildings, good pieces of modern architecture, they represent one

Anthony Betram in the poll, The Archi-

of the first major attempts to translate the modernist ideals of mass production tects Journal 24 May, 1939.

and standardisation into practice. Too often the modern buildings of the thirties, 3 The new style reached the West riding

especially in Britain, were for the affluent 'enlightened', but the scale of the work first in the pithead baths built by the

Miners' Welfare Commission. They were

of the Miners' Welfare Commission, sanctioned by Government, allowed them

begun about 1930 and are worth record-

to avoid the doom of most modernists in Britain; to be part of a primarily aes- ing as pioneer work in the modern style.

thetic movement, rather than social (ist) reformers. Nichlas Pevsner, The Buildings o/England:

West Riding, Yorkshire.

Prior to 1911, when the first legislation regarding pithead baths was passed,4

4 Section 77, The Coal Mines Act 1911.

no pithead baths had been built in Britain by colliery owners, making Britain lag

5 The pit had to be a certain size; a two

well behind its European neighbours. This new legislation, however, did little to

thirds majority of the miners had to be in

change matters, as it was still the owners who were charged with the responsi- favour and the maintenance costs had to

bility of building them, and only when certain stringent conditions were met.5 be kept below specified minimums.

opposite:

Arniston Colliery Pithead Baths, Lothian

(author)

figure 1

Polkommet Colliery Pithead Baths,

Lothian (mwc Annual Report 1937)

57

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TWENTIETH CENTURY In 1913, a set of Government regulations regarding the

ARCHITECTURE I baths was published.6 These advised using the type most com

Continent, consisting simply of a large hall with a high cei

accommodation in the wings. The ceiling area was used to sto

tem of hooks and pulleys. This meant that a miner's workin

stored at the mine, and would not have to be worn going ho

the clean clothes of the miners at work were mixed with other

and were thus practically indistinguishable. Moreover the

clothes was haphazard and rarely successful; unless two heat

given - an improbable luxury - there was a decision between

ers on the ground or drying their clothes in the ceiling area.

The next piece of legislation dealing with pithead baths

Industry Act 1920, which set up the Miners' Welfare Fund.

passed in response to the Sankey Commission report, which i

up to investigate the conditions and structure of the mining

threat of a strike by the newly nationalised mining unions.7 T

dations of the Commission, including nationalisation, had be

by the Lloyd George government, but since the general pub

miners much sympathy during the inquiry, proposals for grea

cepted in the form of the Miners' Welfare Fund, which was

penny levy on each ton of coal produced. This money was t

purposes connected with the social well being, recreation

workers in or about coal mines', although it was specifically

ling the two worst problems in mining areas: poor housing a

ment.8 It was overseen by the Miners' Welfare Commission9

6 General Regulations, Aug 192g, 1913. the relative merits of schemes put forward by local commi

7 For a fuller account of the Sankey Com-

were not high on their agenda, for several reasons. They we

mission and the politics surrounding it

refer to Britain between the Wars 1918-40, C.

with other welfare schemes, expensive to build and, more sur

L. Moffat. ers did not particularly want them. This attitude, which the

8 In 1930, the unemployment rate among deal with in their later programme, was based on several fact

miners was 28.3%, and the overcrowding

plans by colliery owners and governments; fear of the main

rate, for example in the Clyde valley, was

40% (Britain Between the Wars, C. L. Moffat,

borne by the miners; moral objections to communal bathi

The Scottish Thirties, An Architectural Introduc- belief amongst many miners that washing 'wasted the musc

tion, Charles MacKean, p. 12. fore to be avoided.

9 By law, the Commission had to include It was not until 1923 that the Commission built their first pithead bath, at the

two members of the Miners' Federation of

Great Britain, the national trade union,

Linton and Ellington Colliery. It was partly funded by the Ashington Coal Com-

and two members of the Mining Associa- pany, who were more progressive than their contemporaries. Unfortunately, its

tion, the owners' representative body. inhospitable basilica form, possibly a metaphor for the phrase 'cleanliness is

figures 2 & 3

Linton and Ellington Pithead Baths,

by the Ashington Coal Company,

1922

(mwc Annual Report 1923)

58

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

next to godliness', has more to do with the Victorian notion

THE MINERS' WELFAREof charity than

twentieth century welfare. COMMISSION

The Mining Industry Act of 1926 was the beginning of the pithead bath pro-

gramme proper. It was passed after the General Strike, but when the coal strike

which had sparked the general strike was continuing, and was Stanley Baldwin's

response to the determination and stubbornness of both the miners and the own-

ers; his 'legislative revenge' for the fiasco of the General Strike. With another Bill

passed at the same time that abolished the maximum length of shift (a bitter pill

for the miners), it nationalised royalties which the owners had been intent on

keeping.10 The money thus raised was used to set up a separate fund for the provi-

sion of pithead baths.

As a result of the increased building programme, the Miners' Welfare Commis-

sion (the mwc) had appointed Sir Patrick Abercrombie as architectural adviser to

the main organising committee. Before starting the main programme of pithead

baths, he developed a three-point strategy: the setting up of a technical unit, a

study of the precedents and the designing of prototypes.

The technical unit was based in the Commission's headquarters in London,

under the control of John Henry Forshaw.11 Under him were two teams of archi-

tects, each made up of a principal and several assistants. The country was divided

between these teams, north and south, and within each team architects were

allocated specific areas and districts. This policy meant that there was a central

pool of design knowledge available to all the architects and overall standards of

design could be checked and maintained. Moreover the clients, who were the dis-

trict sub-committees of the mwc, had the advantage of dealing with one

architect for all the architectural projects in that area, and this architect could have,

in addition to the general pool of knowledge in the technical unit, a more specific

knowledge of his region's particular characteristics. So, despite the fact that every

pithead bath in the country was built to the same standard, with the same fittings,

they have distinctly different characteristics from region to region. The individual

creativity of the architects multiplied and diversified the types of pithead bath that

were produced.

Since there were few precedents in Britain to study, Forshaw and some assist-

ants made a study trip to Europe where they examined French, Belgian and Ger-

man pithead baths and decided on the pros and cons of layout and design. They

came back with a set of priorities for their own buildings : the importance of light-

ing, the provision of lockers, and the placing of the buildings.

The landscaping surrounding the buildings was always important to the mwc.

This did notalways consist of 'rose beds for miners', butwas an important element

in creating new, well designed, collieries which would replace the ugly, dirty ram-

shackle sheds of the Victorian age. Whenever possible, the mwc used the baths to

generate other developments, and occasionally the owners of the yard would give

extra money for additional facilities to be built at the same time as the baths.

The importance of light, preferably natural, was due to the necessity of keep-

ing the bathhouses clean and hygienic; as well as the atmosphere of health and

brightness which it created, important for miners

10 returning from of

For a fuller account the gloom

the of

political

underground work. This emphasis on health was situation

at the behind

base of

thismany modern

Act, refer to Britain

designs and the way that the mwc designed pitheadBetween

baths the Wars 1918-1940,

showed that it C. L. Moffat.

believed

that the function of the bathhouse was not simply li

toJ. H. Forshaw

clean hadminers,

and dry trained at Liverpool

butwas

under Sir Patrick Abercrombie. The

to improve their welfare and health. Miners normally worked

effects in several

of the First inches

World War of

had allowed

water and, without pithead bath provision, they would

him tobe forced

reach to walk

the position home,

of chief archi-

usually several miles away, in wet clothes. These would

tect atthen haveyoung

a relatively to be

agedried at

and after

leaqving the Miners Welfare Commission

home in time for the next shift. Thus pithead baths reduced ill-health, they less-

in 1940 he became chief architect of the

ened the social stigma of mining and they also had hidden benefits

LCC and forCounty

produced the the miners'

Plan for

wives, whose workload was reduced, and for owners, since

London theagain

1943, miners took

with Sir fewer

Patrick

Abercrombie.

days off through illness.

59

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TWENTIETH CENTURY It was this interpretation of their brief that led the mwc to

ARCHITECTURE I ous project that the Industrial Welfare Society12 had develop

by earlier standards, extravagant. It proposed two locker roo

ers but was much more efficient in terms of the health of th

had applied the philosophy of the production line to the pro

ing type and thus had separate locker rooms, a clean and a

arriving at work would leave his day clothes in the clean loc

fer his soap and towel into the pit locker room, where his

stored. On his way back from work he would leave his pit clot

room and go to the clean locker room via a showering area. Th

was no mixing of coal dust with the clean clothes and men.

The technical unit tried out this new layout in four expe

different areas of the country, testing a range of materials

method of circulation. Their hope was that they could dev

building capable of being used at any colliery.

It soon became clear that no one design could satisfy requi

sites were given by the owners and not chosen by the mwc, th

ward left-over ones which a standard building could never hav

varying water supply and ground conditions all hampered t

were thus forced to look at ways in which they could provide

as many standardised elements as possible. Inspiration came

ist doctrine of functionalism, whereby different functional ar

were expressed in the form of the building. The architects

down into its main components, the two locker rooms and

to create building blocks which could then be re-combined

tion to fit the given sites. The ancillary accommodation, su

room, was then used to further individualise the building on

Thus the idea of the totally standardised building and the

of the modern movement were merged in the design meth

technical unit, modifying and enriching these ideas by prac

a large scale building programme. Even the ways in which t

re-combined began to become part of a larger methodology

more experienced in dealing with sites, three main typolog

These were the linear layout, the cubic layout and the lV pla

The linear type of building consisted of the two locker room

with the shower room normally behind or between them. T

oped for use on long narrow sites that were adjacent to ma

embankments, such as at Blackhall colliery in County Dur

trances were arranged at either end, it was the most obviou

the linear nature of the production line. However it was ofte

uncomfortable symmetrical plan, with one entrance centrall

other forced to be at an extremity, or else with the centrali

ingly giving the service entrance primary importance.

One of the first uses of this plan was the Devon colliery in Fi

the interior shows the beginnings of the functional approach

articulated in the exterior form. The building is still only a

shed. However as the programme progressed, the wide use o

allowed the type to become a dramatic composition, especiall

the greater emphasis on the water tower allowed the archite

ful compositions, such as the one at the Fleets colliery in th

When

i2 The Industrial Welfare Society were an a relatively large installation had to be accommodat

advisory body on the provision of welfare

site, the square plan type would be used with two or even th

buildings in industry and had worked so

at Bestwood in Nottinghamshire, or Rhyme in County Durha

extensively with the MWC that the staff

concerned eventually became tects showed

the core of themselves capable of handling a vertical com

the MWC technical unit.

their more usual single-storey buildings. Unfortunately the

60

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE MINERS' WELFARE

COMMISSION

figure 4

'L' plan Pithead Bath forms (author)

used this form for cheapness, usually in Scotland where collieries tended to be

much smaller, were perhaps the least interesting of the group as they consisted

of a modern facade with three sheds tacked on behind, as at Polmaise in Fife.

But it was in the final type of layout, the 'L' plan that the mwc architects

proved that they could, despite the rigid conditions that they worked under, cre-

ate classic buildings of the thirties in Britain. The 'L' plan type was normally re-

served for prime sites when the colliery owners were taking the opportunity to

modernise the whole yard, using the bathhouse as the centrepiece. In these de-

velopments they would often give additional finance to the mwc for the build-

ing of the bathhouse, so that other accommodation could be added and the

landscaping made much more comprehensive.

The layout consisted of the two locker rooms set at right angles to each other,

normally with the water tower at the crux and the bathhouse set between them at

the back, linking the two wings. Thus each element is articulated in a three-di-

mensional massing which led to the most successful of the Scottish standard

pithead baths, that at Cardowan colliery in Lanarkshire.13

Cardowan shows most clearly the influence of the Dutch architect W. M.

Dudok. The massing and the brick detailing, along with the external pool in the

landscaping, are all strongly reminiscent of Hilversum Town Hall, and this type

of pithead bath is the prime example of this style in Scotland. For architects work- 13 Subject of an article in the RIAS Quarterly,

ing in such an antagonistic and polarised climate as the thirties coal industry, no.

61

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TWENTIETH CENTURY Dudok and the liberal politics of his garden city projects we

ARCHITECTURE I than the more revolutionary moderns. Moreover, much of the

of this time had been generated by similar social legislati

Scandinavian buildings, had received much coverage in the a

The actual building blocks which generated these three lay

selves detailed to the highest degree; every fitting purpose-

grated into a general servicing strategy. The unique demand

on the services (allowing two hundred hot showers to be r

meant that most commercially available systems were ina

ment designed by the mwc, such as shower heads and locke

ard fittings in colliery developments in the post-war era. An

process behind the design of the lockers and bathing cubicl

jÌ0ure 5 concerns of the technical unit.

Canteen, Betteshanger Pithead Baths, There were three main stages of locker design in pithead baths. In the first

Kent, 1934 (mwc Annual Report 19 34)

two experimental baths, each locker was the full height of the nest and contained

ji¿jure 6 vents at the top and the bottom of the door which allowed air to circulate, help-

Womens' Rest Room, Chisnall Hall ing to dry wet pit clothes, as well as preventing mustiness. For the second pair of

Pithead Baths, Lancashire (mwc Annual pithead baths the mwc had developed the double-tier system which allowed the

Report 1934)

same amount of accommodation within almost half the floor area. This type of

locker was also heated by a system of hot steam pipes, which connected to each

nest of lockers at high level, circulated through each locker and then returned at

the end of the line.

The third change was caused by the introduction of a type of plenum heating

which enabled the locker system to work as part of the general heating system,

again reducing capital and maintenance costs. A single concrete duct was split

partly into three: one part providing the heated air for the general atmosphere,

another for the lockers, and the third being the extract from the atmosphere. The

extract system served both as general air and the lockers, as grilles in the base of

the locker indoors allowed the air to be extracted. As a result of growing experi-

ence, controls were developed to control the air flow capacity and air tempera-

ture which produced savings when the baths were not being used to capacity.

The importance that the mwc gave to heated lockers is indicative of their at-

titude to the whole building. It was not an absolute requirement and it meant that

the buildings cost more money to produce, yet they were of primary importance,

as they contributed to the miners' health. Moreover everything was detailed sym-

pathetically; the provision of seemingly insignificant details (seating, the rail

provided for tying shoelaces, the row of mirrors) show the thoughtfiilness of the

architects for the ultimate users of the buildings. The same approach was shown

62

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

in detailing the interiors in such a way as to minimise the

THE MINERS' maintenance costs

WELFARE

which would be incurred by the miners. This canCOMMISSION

be seen most clearly in the de-

sign of the bathing cubicles.

The bathing cubicles were designed from two criteria. First was the cost of

maintenance, which made the architects look at long lasting materials and how

easily they could be cleaned. The second criterion was the privacy of the miners,

crucial in the earlier stages of the programme, when the miners were suspicious

of communal bathing. While the mwc felt that the open bathing areas which

were in common use in Germany were ideal from the first viewpoint, the reluc-

tance of the British miner to accept open public bathing was admitted and the

Commission designed a compromise.

The Commission had inherited a type of cubicle known as the 'double T' from

the earliest British installations, which provided complete privacy, but was ex-

pensive to build and extremely difficult to clean. A mixture of coal dust and soap,

if allowed to dry, will become as hard as cement. Thus each cubicle required

cleaning within a short time after use. Tests carried out by the mwc found that

the 'double T' took ten minutes each to clean. The amount of cleaners thus re-

quired if the bathing hall was to remain hygienic would gready increase the main-

tenance costs. The first type of cubicle which the mwc designed was an 'L' plan,

totally enclosed on three sides, and partially enclosed on the fourth. The next type

did away with the fourth wall and, in order to encourage the largest possible

amount of miners to use the baths, a temporary sail cloth curtain was provided

which could be discarded when the men were more used to communal bathing.

The materials normally used were glazed brick, or tiles on common brick, but

the technical unit experimented with a prefabricated steel panel system (such as

at Haunchwood in Warwickshire) that consisted of steel panels clamped onto

posts. However these panels proved more expensive and less hard-wearing than

traditional materials, although quicker to build. Appendix A:

The Architects involved in the

It can be seen therefore that attempts to use modern préfabrication tech-

Miners' Welfare Commission

niques were made, but the mwc was wise enough to discard them when their

Chief Architect

limitations were apparent, led by the importance to the project of the financial

John Henry Forshaw

and social consequences of its designs. MC MA FRI BA FILA

It was not only in materials and construction techniques

Northern Division

that the mwc were

prepared to experiment. Despite having by the mid-thirties a design methodol-

Chief Architect:

ogy that functioned financially, spatially, and increasingly, architectonically, it

J. A. Dempster friba ai la

experimented with other layouts, usually for collieries which only employed a

F. G. Frizzel ariba Fife, Lothians

hundred or so miners. But it was also open to new ideas and when circular plans

D. D. Jack, LRIBA West Yorkshire

began to be used in the mid-thirties (Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion House,

O. Parry pasistation,

Charles Holden's Arnos Grove London Underground Lanarkshire, Ayrshire

Gatwick Airport

H. Smith

terminal) , the architects of the mwc attempted to LRIBA Cumberland

translate the circulation advan-

tages and possible cost benefits of a circular planSouthern

form Division

to the pithead bath.

The result was the Arniston colliery pithead baths

Chief Architect: the outskirts of Edin-

on

C. G. Kemp

burgh. This was a unique building not only for the mwc ariba

butfila in Scotland in gen-

eral. The accommodation is contained in three concentric

J. W. M. Duddingcircles.

friba The outermost

contained the two locker rooms with the two entrances being Kent

Notts, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, close together so

that on the way to work a miner could simply walk

A. J. Saisein one door and continue

ariba

through the building via the two locker rooms. The middle

South Wales circle contained the

& Forest of Dean

showering area with radial cubicles, and the inner, third,

W. Taylor lriba circle contained the

Southservice

plant and the water tower, minimising the pipe and Wales & Forestrun

of Dean length. The three-

dimensional treatment is probably the best of the W.

thirties circular buildings, with

Woodland ariba

the white rendered curving walls articulating the circular

South Yorkshire movement

& Staffordshire of the inte-

rior. Moreover the clerestory windows allow the J.

flat roof

Browne ariba planes to hover above.

The water tower fins anchor the design and create a vertical

Lancashire, contrast. Arniston

Cheshire & Shropshire

bathhouse, nicknamed 'the spaceship' by local miners isGrounds

Recreation a fantastic

Supervisor: piece of ar-

J. D.the

chitecture which unfortunately was not repeated, O'Kelly AILA

delays and expense caused

63

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TWENTIETH CENTURY by its form leaving it, until its demolition in the seventies, a uniqu

ARCHITECTURE I Thus we can see that the pithead baths of the Miners' Welfare Co

chitects were a valuable contribution to British modernist architecture. Unlike

most of their contemporaries they showed how the tenets of the modern move-

ment were not simply the means to an aesthetic end. Instead they used the basic

principles of Continental modernism: fiinctionalism, standardisation, and mass

production, and enriched them by creatively looking at how these ideas could be

used to solve the financial constraints and the scale of a large building programme.

Function was not regarded as only the articulation of the different parts of a build-

ing but of the underlying purpose of the building; standardisation was not mak-

ing everything the same, but only the parts - creativity being used to make unique

buildings from mass produced elements. Their design experiments and methods

were probably crucial to the better known post-war local authority architects, and

moreover, since they designed the majority of their buildings during the worst of

the Depression in the early thirties, they played an important role in accustoming

Britain to the International Style, especially in areas outside the South-East.

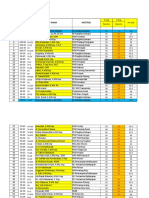

Appendix B Linsay Fife

Scottish Pithead Baths built by the Auchencruive 4 & 5

Miners' Welfare Commission Lanarkshire

(in chronological order) Prestonlinks Lothian

1928 Arniston Lothian

Dalziel & Broomside Lanarkshire 1934

1929 Foulshields Lanarkshire

Kingshill Lanarkshire Minto Fife

1930 Polkemmet Lanarkshire

Auchlochan Lanarkshire Michael Fife

Blairhall Fife Pennyvenie Lanarkshire

Fortissat Lanarkshire Whitehill Lothian

Roslin Fife 1935

Greenrig Lanarkshire Whitehill Lanarkshire

Lochhead Fife Bowhill Fife

Loganlea Lanarkshire Castlehill Lanarkshire

1931 1936

Viewpark Lanarkshire; Kaimes, Ex. Ayr

Bank Ayr Bannockburn Lanarkshire Blairhall, Ex. Fife

Devon Fife Auchincruive 1-3 Lanarkshire

Auchengeich Lanarkshire Newcraighall Lothian

Frances Fife 19 37

Ferniegare Lanarkshire Herbertshire Lanarkshire

Woolmet Lothian Douglas Castle Lanarkshire

1932 Ardenrigg Lanarkshire

Douglas Lanarkshire Whiterigg Lanarkshire

Northfield Lanarkshire Riddochhill Lanarkshire

Whiterigg Lanarkshire Pirnhall Lanarkshire

Bothwell Castle Lanarkshire Hopetoun Lanarkshire

Kinneil Lanarkshire Hauldsworth Ayr

Kaimes Ayr Tillicoutry Fife

East Plean 5 Lanarkshire Gilmerton Lothian

Ramsey Fife Wester Gartshore Lanarkshire

1933 Wester Auchengeich Lanarkshire

Kingshill Lanarkshire 1938

WhitehillAyr Overtoun Lanarkshire

Polmaise 1 & 2 Lanarkshire MauchlineAyr

Lumphinnans 11 & 12 Fife Woodend Lanarkshire

Dewshill Lanarkshire Brora Fife

Aitken Fife Benhar Lanarkshire

Cardownan Lanarkshire Hopetoun Lothian

Manor Powis Fife High House Ayr

Fauldhouse Lanarkshire

64

This content downloaded from

188.28.75.96 on Mon, 24 Aug 2020 16:19:06 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- HistoryDocument6 pagesHistoryw1820820No ratings yet

- The Mediaeval Mason PDFDocument153 pagesThe Mediaeval Mason PDFRaquel Se PNo ratings yet

- A1035301880 12523 7 2018 L6Architecture After IndustralizationDocument52 pagesA1035301880 12523 7 2018 L6Architecture After IndustralizationParth DuggalNo ratings yet

- Tema 3 La Revolución Industrial 22-23Document12 pagesTema 3 La Revolución Industrial 22-23Felicisimo García BarrigaNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument9 pagesIndustrial RevolutionNiket PaiNo ratings yet

- Modern Architecture: Origins & ManifestationsDocument38 pagesModern Architecture: Origins & ManifestationsSadia HusainNo ratings yet

- Construction IndsutryDocument27 pagesConstruction IndsutryMahmooditt NasimNo ratings yet

- Recent Experiences of Tunneling and Deep Excavations in LondonDocument15 pagesRecent Experiences of Tunneling and Deep Excavations in LondonGeotech Designers IITMNo ratings yet

- Modern Architecture: Origins & ManifestationsDocument38 pagesModern Architecture: Origins & ManifestationsDeepan ManojNo ratings yet

- Tin For TomorrowDocument13 pagesTin For TomorrowJovanny HerreraNo ratings yet

- Seven Wonders of Industrial WorldDocument3 pagesSeven Wonders of Industrial WorldVon A. DamirezNo ratings yet

- The Strength, Fracture and Workability of Coal: A Monograph on Basic Work on Coal Winning Carried Out by the Mining Research Establishment, National Coal BoardFrom EverandThe Strength, Fracture and Workability of Coal: A Monograph on Basic Work on Coal Winning Carried Out by the Mining Research Establishment, National Coal BoardNo ratings yet

- Kens Notes Session 4Document16 pagesKens Notes Session 4Lê NguyễnNo ratings yet

- History of Economics Notes - BocconiDocument30 pagesHistory of Economics Notes - BocconiGeorge KolbaiaNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution and Its Impacts On Town Planning PDFDocument10 pagesIndustrial Revolution and Its Impacts On Town Planning PDFGirindra KonwarNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution and Its Impacts On Town PlanningDocument10 pagesIndustrial Revolution and Its Impacts On Town PlanningAditi Sharma100% (7)

- Year Discovery/ Invention Discoverer/ Inventor Purpose/ FunctionDocument2 pagesYear Discovery/ Invention Discoverer/ Inventor Purpose/ Function在于在No ratings yet

- Lecture 2 The Industrial RevolutionDocument84 pagesLecture 2 The Industrial RevolutionvivianNo ratings yet

- Harry Macdonald SteelsDocument8 pagesHarry Macdonald Steelsslambo69No ratings yet

- Concrete ShipsDocument112 pagesConcrete ShipsDábilla Adriana BehrendNo ratings yet

- Designing-Playspaces-For-The-Emerging-Society-Of-Car-Owners-In-Post-War-Council-Housing-In-Britain - Content File PDFDocument17 pagesDesigning-Playspaces-For-The-Emerging-Society-Of-Car-Owners-In-Post-War-Council-Housing-In-Britain - Content File PDFIoana INo ratings yet

- Ap Eh CH 20 NotesDocument7 pagesAp Eh CH 20 NotesAkash DeepNo ratings yet

- Cornell Notes Topic/Objective: Name:Daksha Jadhav CH 27 Class/Period: 1 Date:3/19/16 Questions: NotesDocument8 pagesCornell Notes Topic/Objective: Name:Daksha Jadhav CH 27 Class/Period: 1 Date:3/19/16 Questions: NotesdakshaNo ratings yet

- History of ArchitectureDocument15 pagesHistory of ArchitectureTanya SirohiNo ratings yet

- HIST 115 Lecture 10 NotesDocument8 pagesHIST 115 Lecture 10 NotesschehzebNo ratings yet

- Stabilising The Leaning Tower of Pisa: The Evolution of Geotechnical SolutionsDocument34 pagesStabilising The Leaning Tower of Pisa: The Evolution of Geotechnical SolutionsMiguel GaravitoNo ratings yet

- Radioactive Isotopes - Used As Tracers inDocument3 pagesRadioactive Isotopes - Used As Tracers inYay or Nay Panel DiscussionNo ratings yet

- Unit VDocument12 pagesUnit VYeonjun ChoiNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution in Britain HandoutDocument6 pagesIndustrial Revolution in Britain HandoutAlriNo ratings yet

- Coal in Victorian BritainDocument6 pagesCoal in Victorian BritainPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- 07 The Industrial RevolutionDocument3 pages07 The Industrial RevolutionHeidy Teresa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution 1760-1840: By-Himanshi and RadhikaDocument15 pagesIndustrial Revolution 1760-1840: By-Himanshi and Radhikaradhika goelNo ratings yet

- Journal 6 - House of TomorrowDocument27 pagesJournal 6 - House of TomorrowRatnawulan UNPNo ratings yet

- Estratto - Clil - Storia Ind Rev PDFDocument18 pagesEstratto - Clil - Storia Ind Rev PDFChiaraNo ratings yet

- A Short History of M&I Materials Limited and Its Heritage: 1901-2010Document32 pagesA Short History of M&I Materials Limited and Its Heritage: 1901-2010Max LiaoNo ratings yet

- AP EH Unit 6 NOTESDocument10 pagesAP EH Unit 6 NOTESKamil FikriNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Science & Technology On Society During The Industrial Revolution A.D. 1730 - A.D. 1950 in The Modern WorldDocument31 pagesThe Impact of Science & Technology On Society During The Industrial Revolution A.D. 1730 - A.D. 1950 in The Modern WorldEmgelle JalbuenaNo ratings yet

- 15 The Industrial RevolutionDocument17 pages15 The Industrial RevolutiondayadaypolinesjhonjerickNo ratings yet

- Hrading LectureDocument20 pagesHrading LectureMohamed Ismail ShehabNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument49 pagesIndustrial Revolutionhuongleung100% (1)

- Unit IDocument76 pagesUnit Imocharla aravindNo ratings yet

- Second Industrial RevolutionDocument4 pagesSecond Industrial RevolutionFrancesco PaceNo ratings yet

- Note On 313Document6 pagesNote On 313Amusa AdeolaNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Revolution: According To The View of Different AuthorsDocument8 pagesThe Industrial Revolution: According To The View of Different AuthorsFotografíaTresAlfilesNo ratings yet

- The Industrial RevolutionDocument6 pagesThe Industrial RevolutionMarrien EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Mckay Irm Ch21Document19 pagesMckay Irm Ch21joshpatel99100% (1)

- Locomotives of the Victorian Railway: The Early Days of SteamFrom EverandLocomotives of the Victorian Railway: The Early Days of SteamNo ratings yet

- A Glimpse Into London's Early Sewers by Mary GaymanDocument5 pagesA Glimpse Into London's Early Sewers by Mary GaymanKatherine McNennyNo ratings yet

- MARSDEN e SMITH - 2005 - Engineering Empires - A Cultural History of Technology in Nineteenth-Century BritainDocument364 pagesMARSDEN e SMITH - 2005 - Engineering Empires - A Cultural History of Technology in Nineteenth-Century BritainGuilherme SuzinNo ratings yet

- Roman Civil Engineering Has Lessons For The Modern WorldDocument6 pagesRoman Civil Engineering Has Lessons For The Modern WorldPablo PerezNo ratings yet

- Middle Ages and RenaissanceDocument66 pagesMiddle Ages and RenaissanceMYKEE LOPEZNo ratings yet

- ENVR 2020 Urban Air PollutionDocument43 pagesENVR 2020 Urban Air PollutionAnson Kwun Lok LamNo ratings yet

- manualChemicalTechnology6 AlkalIndustry1916Document122 pagesmanualChemicalTechnology6 AlkalIndustry1916Oth JNo ratings yet

- 1985 Ironworks Ironbridge 32140 LightDocument444 pages1985 Ironworks Ironbridge 32140 LightLuis SarNo ratings yet

- 2nd Industrial Revolution MetranGlyzylDocument18 pages2nd Industrial Revolution MetranGlyzylChinita Chin AcaboNo ratings yet

- Big Ben: The Bell, the Clock and the TowerFrom EverandBig Ben: The Bell, the Clock and the TowerRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Design of Reinforced Concrete StructuresDocument45 pagesDesign of Reinforced Concrete StructuresAnonymous ELujOV3No ratings yet

- Pipeline ROUDocument17 pagesPipeline ROUchezy100% (2)

- Conservation Adaptation EAAE 65Document386 pagesConservation Adaptation EAAE 65Iulia PetreNo ratings yet

- Environmental Rehabilitation and Repurposing Toolkit - Platform For Coal Regions in TransitionDocument30 pagesEnvironmental Rehabilitation and Repurposing Toolkit - Platform For Coal Regions in TransitionCatharsis HaddoukNo ratings yet

- FORGOTTEN INFRASTRUCTURE The Future of The Industrial MundaneDocument114 pagesFORGOTTEN INFRASTRUCTURE The Future of The Industrial MundaneCatharsis HaddoukNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Resolution EbookDocument108 pagesThe Industrial Resolution EbookJack MoNo ratings yet

- DX195626 PDFDocument307 pagesDX195626 PDFSidra JaveedNo ratings yet

- Li & Fung LimitedDocument2 pagesLi & Fung Limitedeguno12No ratings yet

- Small Scale Industries in IndiaDocument18 pagesSmall Scale Industries in IndiaTEJA SINGHNo ratings yet

- Business Economics - Neil Harris - Summary Chapter 3Document2 pagesBusiness Economics - Neil Harris - Summary Chapter 3Nabila HuwaidaNo ratings yet

- A Final Board Packet August 7, 2013 - 0.... 5Document199 pagesA Final Board Packet August 7, 2013 - 0.... 5نيرمين احمدNo ratings yet

- BARC CertificationDocument1 pageBARC CertificationsPringShock100% (6)

- The Birth Certificate: Rehabilitative Services" (HRS) - Each STATE Is Required To Supply The UNITED STATES WithDocument4 pagesThe Birth Certificate: Rehabilitative Services" (HRS) - Each STATE Is Required To Supply The UNITED STATES Withpandabearkt50% (2)

- AMT4SAP - Junio26 - Red - v3 PDFDocument30 pagesAMT4SAP - Junio26 - Red - v3 PDFCarlos Eugenio Lovera VelasquezNo ratings yet

- BSP ReportDocument20 pagesBSP ReportRosemarie CabahugNo ratings yet

- Eco Dev Chapter 2 Overview of Economic DevelopmentDocument26 pagesEco Dev Chapter 2 Overview of Economic DevelopmentVermatex PHNo ratings yet

- The Rite-The Making of A Modern Exorcist - Matt BaglioDocument130 pagesThe Rite-The Making of A Modern Exorcist - Matt BaglioFrancisco J. Salinas B.No ratings yet

- Hegels Theory of The Modern State XYZDocument10 pagesHegels Theory of The Modern State XYZMaría CastroNo ratings yet

- International Economic (Group Assignment)Document12 pagesInternational Economic (Group Assignment)Ahmad FauzanNo ratings yet

- Ecosystem Services of The Congo Basin ForestsDocument33 pagesEcosystem Services of The Congo Basin ForestsGlobal Canopy Programme100% (3)

- Ceramic Tiles - Official Gazette 27 (10234)Document16 pagesCeramic Tiles - Official Gazette 27 (10234)NajeebNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Selected Financial TermsDocument13 pagesGlossary of Selected Financial Termsnujahm1639No ratings yet

- GSTR1 Stupl 08ABFCS1229J1Z9 November 2021 BusyDocument92 pagesGSTR1 Stupl 08ABFCS1229J1Z9 November 2021 BusyYathesht JainNo ratings yet

- $Ffhvvwr6Dih:Dwhu: Charting The Progress of PopulationsDocument5 pages$Ffhvvwr6Dih:Dwhu: Charting The Progress of PopulationskatoNo ratings yet

- UN-Habitat Country Programme Document - KenyaDocument32 pagesUN-Habitat Country Programme Document - KenyaUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)No ratings yet

- Notice 11120 02 Apr 2024Document669 pagesNotice 11120 02 Apr 2024bhattacharya.devangana2No ratings yet

- Economic ResourcesDocument12 pagesEconomic ResourcesMarianne Hilario0% (2)

- Yong Le: Beijing Huaxia Yongleadhesive Tape Co., LTDDocument9 pagesYong Le: Beijing Huaxia Yongleadhesive Tape Co., LTDColors Little ParkNo ratings yet

- Collection of Direct Taxes - OLTASDocument36 pagesCollection of Direct Taxes - OLTASnalluriimpNo ratings yet

- Section 125 Digested CasesDocument6 pagesSection 125 Digested CasesRobNo ratings yet

- CPO-5 Block - Llanos Basin - Colombia, South AmericaDocument4 pagesCPO-5 Block - Llanos Basin - Colombia, South AmericaRajesh BarkurNo ratings yet

- Unclaimed Deposit List 2008Document51 pagesUnclaimed Deposit List 2008Usman MajeedNo ratings yet

- Tax Reviewer For MidtermDocument4 pagesTax Reviewer For Midtermjury jasonNo ratings yet

- Tax AssignmentDocument5 pagesTax AssignmentdevNo ratings yet

- Lesson 23 Illustrating Simple and Compound InterestDocument12 pagesLesson 23 Illustrating Simple and Compound InterestANGELIE FERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- TCSDocument4 pagesTCSjayasree_reddyNo ratings yet

- Nama Peserta BPPDocument53 pagesNama Peserta BPPInge Syahla KearyNo ratings yet