Professional Documents

Culture Documents

14 Un Estudio de Los Efectos de Los Patrones de Masticación

Uploaded by

Welinson Chávez ríosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

14 Un Estudio de Los Efectos de Los Patrones de Masticación

Uploaded by

Welinson Chávez ríosCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2001 28; 1048±1055

A study of the effects of chewing patterns

on occlusal wear

S. K. KIM, K. N. KIM, I. T. CHANG & S. J. HEO Department of Prosthodontics, College of Dentistry, Seoul

National University, 28 Yeongundong, Jongrogu, Seoul, South Korea

SUMMARY The chewing cycle is a functional move- of non-working facets were calculated for each

ment, closely related to occlusion, the neuromus- group. The occlusal wear values in all teeth and in

cular system and the central nervous system. each segment, obtained by the use of the ordinal

Although actual chewing paths are complicated scale did not vary signi®cantly between the chop-

and vary from individual to individual, there are ping and the grinding type group. However, the

two typical patterns. One is more vertical in nature occlusal wear values of the grinding type group in

and is similar to a chopping movement. The other all teeth and in posterior teeth segments, obtained

is a more lateral type that is similar to a grinding by the use of Woda's arbitrary scale, were signi®-

movement. The purpose of this study was to cantly greater than those of the chopping type

evaluate the effects of chewing patterns on occlusal group. Frequencies of non-working facets in pos-

wear. Fifteen subjects exhibiting a chopping±chew- terior teeth showed no signi®cant differences

ing pattern and 15 subjects exhibiting a grinding± between the groups.

chewing pattern were selected using a jaw tracking KEYWORDS: chewing pattern, chopping, grinding,

device. The occlusal wear values, obtained by both jaw tracking device, occlusal wear, non-working

ordinal and Woda's arbitrary scales, and frequencies 1 wear facet

chopping movement. In this pattern, very little sliding

Introduction

of the teeth is observed, particularly during the opening

Chewing movements performed by co-operative inter- movement. The path is observable only on the chewing

actions among various stomatognathic organs, their side. The other pattern is a more lateral (horizontal)

proprioceptors, and higher brain centres are closely type, similar to a grinding movement. Here there is a

related to the functional occlusal system. A change in distinct sliding of the teeth, especially to the non-

any of the information related to occlusion, the tempo- chewing side during the opening movement.

romandibular joint, or the masticatory muscles will Gradual attrition of the occlusal surfaces of the teeth

affect the patterns of the chewing movements. A appears to be a general physiological phenomenon

number of researchers have argued that occlusion may found in all mammals, in every civilization and at all

in¯uence the chewing path. It has been supported that a ages. Relatively few studies of tooth wear have been

part of the path of lateral excursions is present within reported in the literature. This lack of detailed research

the chewing path and the path is affected by cuspal is partly because of problems involved in measuring

inclinations (Schweitzer, 1961). In some research, the techniques. The most frequently used methods are

relationship between the chewing path and the occlu- based on clinical grading of the amount of wear of tooth

sion has been supported (Adams & Zander, 1964). substance. As the wear of teeth in contemporary

Actual chewing paths are complicated and varied industrialized populations is small, the ordinal scale of

(Schweitzer, 1961). However, despite the presence of these methods is not sensitive enough for the study of

various patterns, two typical patterns have been con- tooth wear in normal young permanent dentition

®rmed. One is more vertical in nature similar, to a (NystoÈm et al., 1990). On the other hand, planimetric

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd 1048

EFFECTS OF CHEWING PATTERNS ON OCCLUSAL WEAR 1049

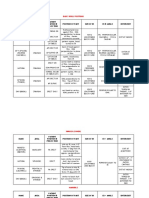

methods (Russel & Grant, 1983) and Woda's arbitrary Table 1. Questionnaire on factors related to dental attrition

scale (Woda et al., 1987) provide a continuous and

more accurate scale that makes it possible for detailed Selected answer

Questions for study

information to be collected. Values obtained by the

planimetric methods and Woda's arbitrary scale have Do you spend much time in a dusty No

shown a signi®cant correlation for quanti®cation of the environment?

Do you use your teeth in your work? No

occlusal wear (Gourdon et al., 1987).

Have you had a dry mouth for a long No

The number and extent of facets of wear on all teeth

period of time?

has seemed to be more closely related to the length of Do you often have acid regurgitation? No

slide rather than the age of the individual (Reynolds, Do you often vomit? No

1970). Many facets have been observed on the occlusal Do you often clench or grind your teeth? No

surfaces of the grinding type group while they were Does your diet include

Citrus fruits? 1±2 times a week

limited to only the cuspid and ®rst premolar in the

Apples? 1±2 times a week

chopping type group (Nishio et al., 1988). The purpose Tomatoes? 1±2 times a week

of this study was to evaluate the effects of chewing Coke/Pepsi? 1±2 times a week

pattern type on occlusal wear. Fruit juices? 1±2 times a week

Cider? 1±2 times a week

Do you suffer from

Materials and methods Frequent headache? No

Pain in your jaw and/or face? No

A preliminary study was conducted on 120 students of Dizziness? No

Seoul National University Dental College who had a Tinnitus? No

complete healthy dentition and were between 23 and

25 years of age. Their selection was predicated on the record chewing movements for 10 s from 5 s after the

following criteria: absence of missing teeth (excepting start of chewing (Jeong & Kim, 1987; Lee et al., 1991).

third molars), caries, periodontal disease, bruxism, TMJ When placing the magnet, the centre of the magnet was

disorders, restorations and a history of occlusal or lined up with frenum, but was placed above the frenum

orthodontic therapy. Furthermore, good occlusion with at the gingival third of the teeth. The sensor array was

molar relationship in Angle class I and coincidence placed on the student's head, so that the upper crossbar

between maxillary and mandibular midlines were was parallel to the eyes (interpupillary line). The side

required to be present, along with regular teeth bar was parallel to the Frankfurt horizontal plane.

alignment and little evidence of dental wear. The third The preliminary study indicated two typical chewing

molars, when present, were not included in the pattern groups. One type was a group exhibiting a

analysis. To exclude other factors related to dental grinding movement path, similar to an herbivorous

attrition, a questionnaire related to possible background animal, from centric occlusion to the opposite side.

factors of importance for dental attrition (dietary, Hereafter, this grinding type is called G-type (Fig 1a, b).

environmental, working and parafunctional factors), The other group exhibited a chopping movement-type

signs and symptoms of functional disturbances of the path (similar to a carnivore) with no slide to the

masticatory system and recurrent headache (Carlsson opposite side. Hereafter, the chopping type is referred

et al., 1985) was given to 120 persons (Table 1). to as C-type (Fig 2a, b). Of the 84 persons so tested, 30

According to the results of the questionnaire, 36 people persons exhibiting the two standard types of chewing

who had possible factors of importance for dental patterns were selected for this study. Fifteen displayed

attrition or functional disturbances of the masticatory the C-type chewing pattern (age 24 1 years, 10

system were excluded. Subsequently, in order to males and 5 females). Another 15 presented the G-type

identify chewing patterns, 84 students were instructed pattern (age 24 1 years, 10 males and 5 females).

to chew peanuts at arbitrary rhythms on a speci®c side

of the mouth. Each of both unilateral side chewings was

Occlusal wear analysis by the use of the ordinal scale

performed by each student. The BioPAKÒ* was used to

The ordinal scale was used to measure occlusal wear

*Bioresearch Inc., Milwaukee, WI, USA. values of subjects. The following scale of original

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

1050 S . K . K I M et al.

Fig. 1. Grinding-type: (a) right side

chewing, (b) left side chewing.

attrition was applied: 0 no or little wear of enamel ment in judgement between observers was very high

only; 1 marked wear facets of enamel; 2 wear into (96%).

dentin; 3 extensive wear into dentin (> 2 mm2);

and 4 wear into secondary dentin. On the basis of

Occlusal wear analysis by the use of Woda's

these criteria, an assessment was performed on sub-

arbitrary scale (Woda et al., 1987)

jects through clinical oral examinations. To verify the

examiner's ability to interpret the scores of incisal or Impressions of both dental arches were made in silicone

occlusal wear, an interindividual comparison was elastomer and only the dental part of the impression

carried out on a randomly selected sample of 16 was poured in arti®cial stone. Microbubbles were

subjects. Each subject was scored independently by eliminated from maxillary and mandibular casts, and

each of the three examiners. Only 20 teeth of 448 the form, dimension, and location of wear facets were

teeth showed disagreed scores. Therefore, the agree- analysed with a magnifying lens. These observations

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

EFFECTS OF CHEWING PATTERNS ON OCCLUSAL WEAR 1051

Fig. 2. Chopping-type: (a) right side

chewing, (b) left side chewing.

were then drawn on a cast of each arch, with care taken 1 One or several facets located only on the palatal or

to reproduce both the form and location of the wear buccal surface of the tooth.

facets in relation to grooves and margins. We observed 2 One or several facets present only on the incisal edge.

that all available wear facets were engaged during 3 One or several facets present on the incisal edge

working and non-working simulated contact move- and also on the palatal or buccal surfaces, but occupy-

ments (Fig. 3). Both types of wear facets (working and ing less than one-third of the longitudinal length of the

non-working) in posterior teeth were shaded using tooth crown.

different colours. Woda's arbitrary scale used to quan- 4 One or several facets present on the incisal edge

tify the surface of wear facets. Anterior teeth were and also on the palatal or buccal surfaces, and occupy-

assigned the following Woda's arbitrary values (1±4) ing more than one-third of the longitudinal length of

(Fig. 4): the tooth crown.

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

1052 S . K . K I M et al.

Posterior teeth were assigned the following Woda's 4 Facets occupying in bucco-lingual direction three

arbitrary values (1±5) (Fig. 5): complete cusp sides (external working, internal work-

1 Facets occupying in bucco-lingual direction less ing, and non-working) that are not situated in the same

than one-third of cusp side. frontal plane.

2 Facets occupying in bucco-lingual direction more 5 Facets occupying in bucco-lingual direction three

than one-third of cusp side. complete and contiguous cusp sides situated in the

3 Facets occupying a total cusp side. same frontal plane.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups was tested by means of

t-test (SPSS/PC+). The level of statistical signi®cance

used was P < 0á05.

Results

Occlusal wear values obtained by the use

of the ordinal scale (Table 2)

Fig. 3. Diagram of three functional cusp sides on which working Mean and standard deviations were calculated for each

facets (1, 1¢, 3, 3¢) and non-working facets (2, 2¢) are distributed.

group in all teeth and in each segment. These ®gures

were used for a comparative study of the occlusal wear

values of the G-type and C-type subjects. The mean

occlusal wear value in all teeth, obtained by the use of

the ordinal scale, was not signi®cantly different

between the C-type and G-type group. The occlusal

wear values in each segment, obtained by the use of

ordinal scale showed very small differences between

the two groups. However, signi®cant differences

between the C-type and G-type group were not

observed.

Table 2. Occlusal wear values obtained by the ordinal scale

method

Fig. 4. Diagram of Woda's arbitrary criteria chosen to qualify

wear facets of incisors and canines.

Site C-type G-type

All teeth 1á1736 0á168 1á2132 0á178

Segment

UP* 1á0583 0á114 1á1250 0á206

LP² 1á0250 0á097 1á0500 0á092

P³ 1á0417 0á099 1á0875 0á143

UA§ 1á2667 0á242 1á3333 0á227

LA¶ 1á3444 0á392 1á3444 0á299

A** 1á3056 0á290 1á3389 0á243

*Upper posterior teeth.

²

Lower posterior teeth.

³

Posterior teeth.

§

Upper anterior teeth.

¶

Fig. 5. Diagram of Woda's arbitrary criteria chosen to qualify Lower anterior teeth.

wear facets of molars and premolars. **Anterior teeth.

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

EFFECTS OF CHEWING PATTERNS ON OCCLUSAL WEAR 1053

Table 3. Occlusal wear values obtained by Woda's arbitrary scale posterior segment. These ®gures were used to com-

method pare the difference of the frequency between the

C-type and G-type group. The frequencies of

Site C-type G-type

non-working facets in posterior teeth exhibited no

All teeth 2á8792 0á377 3á1771 0á281 signi®cant divergence between the C-type and G-type

Segment groups. Working facets were found in all posterior

UP* 2á1583 0á514 2á9839 0á403 teeth regardless of chewing patterns. Non-working

LP² 3á2250 0á668 3á6250 0á263 facets were found in 82% of upper posterior teeth, in

P³ 3á1979 0á546 3á8042 0á301 71% of lower posterior teeth and in 79% of posterior

UA§ 3á0444 0á582 3á0222 0á672 teeth.

LA¶ 2á0889 0á139 2á0778 0á124

A** 2á5667 0á317 2á5500 0á356

*Upper posterior teeth. Discussion

²

Lower posterior teeth.

³ Chewing movements are smoothly performed func-

Posterior teeth.

§

Upper anterior teeth.

tional movements when the occlusion, temporoman-

¶

Lower anterior teeth. dibular joint, masticatory muscles, and higher brain

**Anterior teeth. centres constituting the functional occlusion system

function in harmony with one another. Therefore,

Occlusal wear values obtained by the use disturbances occurring in any of these will affect the

of Woda's arbitrary scale (Table 3) chewing movements. Indeed, disturbance of the chew-

Mean and standard deviations of occlusal wear values ing movement is well recognized in patients with

were calculated for each group in all teeth and in each dysfunction. In our clinical practice, we often encoun-

segment. The mean occlusal wear value in all teeth, ter situations in which the chewing path improves

obtained by the use of Woda's arbitrary scale, was with the improvement of symptoms. Among studies

signi®cantly greater in the G-type than in the C-type examining the chewing path from the viewpoint of

group (P < 0á05). This result was similar to that repor- occlusion, there have been reports which took the

ted by Nishio et al. (1988). Furthermore, the occlusal position that no occlusal contact was observed during

wear values in posterior teeth segments, obtained by chewing (Jankelson, 1953). However, of late, there

the use of Woda's arbitrary scale, were signi®cantly have been other reports emphasizing a relationship

greater in the G-type than in C-type group (P < 0á05). between the chewing path and occlusion. Some

However, the occlusal wear values in anterior teeth was patients with a steep cuspal inclination displayed a

not found to be signi®cantly different between the more vertical type of chewing movement, while others

C-type and G-type group. with gentle cuspal inclination exhibited a more lateral

type of chewing movement (Nishio et al., 1988). Actual

chewing paths are complicated and vary from individ-

The frequency of non-working facets (Table 4) ual to individual. Therefore, it would seem that a

The frequencies of non-working facets were calcula- detailed classi®cation would further complicate the

ted for each group in all posterior teeth and each study of the relationship with occlusion. However,

despite the presence of various patterns, two typical

Table 4. Frequency of non-working facets patterns were con®rmed in this study. One is a more

vertical type of movement similar to a chopping

Site C-type G-type movement, with very little sliding of the teeth,

§ particularly during the opening movement, and show-

UP* 6á2667 1á486 6á8667 1á356

LP² 5á6667 1á291 5á7333 1á624 ing a path only on the chewing side. The other is a

P³ 11á9333 1á907 12á6000 2á828 more lateral (horizontal) type, similar to a grinding

movement, with a distinct sliding of the teeth, pre-

*Upper posterior teeth.

²

Lower posterior teeth. dominantly to the non-chewing side during the open-

³

Posterior teeth. ing movement, and showing a path across the chewing

§

Number of teeth with non-working facets. and non-chewing sides. Of the 84 subjects examined,

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

1054 S . K . K I M et al.

19 patients exhibitied the G-type and 15 displayed the cuspid and ®rst premolar in the C-type group. How-

C-types. The remaining 50 subjects displayed interme- ever, in this study, the occlusal wear facets were found

diate chewing paths that fell into neither of the two in all posterior teeth of the C-type group. Thus, it

patterns. It is important to compare the occlusions of appears that chewing patterns have little effect on

normal subjects exhibiting the two typical patterns in occlusal wear. Many factors of importance for occlusal

studying the chewing path in relation to occlusion. For wear, other than the chewing patterns, have had more

this reason, normal subjects with G-type and C-type effect on these subjects (Hugoson et al., 1988; Dahl

chewing movement patterns were selected. Projections et al., 1989). Therefore, chewing patterns are an

on the frontal plane of the paths of lateral border aetiological factor, having little effect on occlusal wear.

movement and opening and closing movement were In this study, the occlusal wear values of the C-type

used for comparison, illustrating the differences in the and the G-type groups, obtained by the use of ordinal

occlusal wear values between the two groups. In this scale, were not signi®cantly different. However, the

study, one difference is that the occlusal wear values, occlusal wear values obtained by the use of Woda's

obtained by the use of Woda's arbitrary scale, were arbitrary scale, were signi®cantly greater in the G-type

greater in the G-type group than in the C-type group. versus the C-type group. A difference in the results

These appear to relate to the facets during the may be because of: ®rst, the ordinal scale is not

movement corresponding to the closing phase des- suf®ciently sensitive for the study of occlusal wear in

cribed by Schweitzer (Schweitzer, 1961). Inclinations normal young permanent dentition (NystoÈm et al.,

of movement paths shown on the frontal projections of 1990). Second, the difference of chewing movements

lateral border movement paths were gentle in the between the C-type and G-type group is related

G-type group and relatively steep in the C-type group. primarily to the length of the slide. Therefore, Woda's

When the fact that the G-type group showed gentle arbitrary scale is more suitable for identifying the

inclinations of lateral border movement and the occlusal wear values attributed to chewing patterns. In

presence of many facets on the occlusal surfaces of this study, the occlusal wear values in the anterior

the posterior teeth is considered and the above results teeth of the C-type and the G-type groups, obtained by

are added together, the following hypothesis can be the use of Woda's arbitrary scale, was not signi®cantly

derived: the upper and lower posterior teeth of the different. It appears that occlusal wear in anterior teeth

G-type group are relatively close to each other not only 2,3 is more affected by incisal guidance (Schweitzer, 1961;

in centric occlusion, but also in lateral positions, while 2,3 Silness et al., 1993). In this study, all dental arches

the upper and lower posterior teeth of the C-type presented numerous wear facets. All the teeth dis-

group are separated in lateral positions. There are played facets. Working facets were found in all

many factors that can in¯uence the type and rate of posterior teeth. Non-working facets were found in

wear (Dahl et al., 1989). These factors are time/age, 82% of upper posterior teeth, in 71% of lower

gender, occlusal conditions, hyperfunction, bite force, posterior teeth and in 79% of posterior teeth. Wear

gastrointestinal disturbances, nutrition, environmental facets in posterior teeth were seen on the surface of the

factors, salivary factors, as well as other factors. The three functional cusp sides. In premolars, working

factors of importance for dental attrition have been facets were usually absent from internal working cusp

shown to be bruxism, biting habits, and fruit juices sides because of the low height of mandibular lingual

(Johansson et al., 1991). But there is no correlation cusp, which prevented any possibility of contact with

between subjects from differing geographic and/or this surface.

climate habits and the severity of tooth wear. Reynolds The ideas developed in this article raise additional

reported that the number and extent of facets of wear points of clinical interest.

was related as follows: ®rst, the length of the slide from 1. The chewing pattern is one of the aetiological factors

terminal hinge relation to maximum intercuspation, related to the occlusal wear.

second, a lack of eccentric disclusion of the posterior 2. Occlusal contacts are surfaces that increase in diam-

teeth (Reynolds, 1970). Many facets were observed on eter with the development of abrasion. When pros-

the occlusal surfaces of the G-type models (Nishio thetic treatment or occlusal correction are required,

et al., 1988). These seemed to be the result of many occlusal surfaces in a convex form may not really be

years of G-type chewing. They were limited to only the necessary.

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

EFFECTS OF CHEWING PATTERNS ON OCCLUSAL WEAR 1055

3. The presence of non-working facets and the evi- JOHANSSON , A., FAREED , K. & OMAR , R. (1991) Analysis of possible

dence of non-working contacts during chewing indicate factors in¯uencing the occlurrence of occlusal tooth wear in a

young Saudi population. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 49, 139.

that a prophylactic elimination of all non-working

LEE , J.H., KIM , K.N. & CHANG , I.T. (1991) A comparative study of

contacts will eliminate a great part of the functional the effect of the CR-CO discrepancy on the mandibular

®eld of mastication. movements. Journal of Korean Academy of Prosthodontics, 29, 295.

NISHIO , K., MIYAUCHI , S. & MARUYAMA , T. (1988) Clinical study

on the analysis of chewing movement in relation to occlusion.

References Journal of Craniomandibular Practice, 6, 113.

NYSTo È M , M., KO

YSToM È NOÈ NEN , N., ALALUUSUA , S., EVA

ONONEN È RAHTI , M. &

VARAHTI

ADAMS , S.H. & ZANDER , H.A. (1964) Functional tooth contact in

VARTIOVAARA , J. (1990) Development of horizontal tooth wear

lateral and in centric occlusion. Journal of the American Dental

in maxillary anterior teeth from ®ve to 18 years of age. Journal

Association, 69, 465.

of Dental Research, 69, 1765.

CARLSSON , G.E., JOHANSSON , A. & LUNDOVIST , S. (1985) Occlusal

REYNOLDS , J.M. (1970) Occlusal wear facets. Journal of Prosthetic

wear. A follow-up study of 18 subjects with extensively worn

Dentistry, 20, 367.

dentitions. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 43, 83.

RUSSELL , M.D. & GRANT , A.A. (1983) The Relationship of occlusal

DAHL , B.L., KROGSTAD , B.S., GAARD , B. & ECKERS -BERG , T. (1989)

wear to occlusal contact area. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 10,

Differences in functional variables, ®llings, and tooth wear in

383.

two group of 19-year-old individuals. Acta Odontologica Scandi-

SCHWEITZER , J.M. (1961) Masticatory function in man. Journal of

navica, 47, 35.

Prosthetic Dentistry, 11, 625.

GOURDON , A.M., BUYLE -BODIN , Y., WODA , A. & FARAJ , M. (1987)

SILNESS , J., JOHANNESSEN , G. & ROYNSTAND , T. (1993) Longitud-

Development of an abrasion index. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry,

inal relationship between incisal occlusion and incisal tooth

57, 358.

wear. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 51, 15.

HUGOSON , A., BERGENDAL , T., EKFELDT , A. & HELKIMO , M. (1988)

WODA , A., GOURDON , A.M. & FARAJ , M. (1987) Occlusal contacts

Prevalence and severity of incisal and occlusal tooth wear in an

and tooth wear. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 57, 85.

adult swedish population. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 46, 255.

JANKELSON , B. (1953) The physiology of the stomatognathic

system. Journal of the American Dental Association, 46, 375. Correspondence: S.J. Heo, Department of Prosthodontics, College of

JEONG , J.K. & KIM , C.W. (1987) a study chewing movements Dentistry, Seoul National University, 28 Yeongundong, Jongrogu,

between dentate and complete denture group. Journal of Korean Seoul, 110±749, South Korea.

Academy of Prosthodontics, 25, 181. E-mail: heosj@plaza.snu.ac.kr

ã 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28; 1048±1055

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Carnaby Videofluoroscopic Data SheetDocument4 pagesCarnaby Videofluoroscopic Data SheetKanky Espinoza RuizNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- What Are "Wisdom Teeth?"Document4 pagesWhat Are "Wisdom Teeth?"Ghazwan M. Al-KubaisyNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Jurnal Critical Patient MonitoringDocument10 pagesJurnal Critical Patient MonitoringKhiyarotul laeli100% (1)

- Physical Assessment EarsDocument65 pagesPhysical Assessment EarsDeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Traumatic Optic Neuropathy - Prof. N. KarthikeyanDocument22 pagesTraumatic Optic Neuropathy - Prof. N. KarthikeyanDobrin_Nicolai_8219No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Crown and Root Landmarks, Division Into Thirds, Line Angles and Point AnglesDocument62 pagesCrown and Root Landmarks, Division Into Thirds, Line Angles and Point AnglesSara Al-Fuqaha'No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- RetentionDocument39 pagesRetentionShiva PrasadNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Meniere's DiseaseDocument2 pagesMeniere's DiseaseNoelyn BaluyanNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- What Is Goitre?: Thyroid GlandDocument3 pagesWhat Is Goitre?: Thyroid Glandflex gyNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Pupillary Dilatation ReflexDocument7 pagesPupillary Dilatation ReflexEden Canonizado ChengNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- 4.15 DR. ROBERTO MIRASOL HYperthyroidism PSEM 2017 1 PDFDocument89 pages4.15 DR. ROBERTO MIRASOL HYperthyroidism PSEM 2017 1 PDFjackie funtanilla100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Endoscopic Surgery of The Lateral Nasal Wall, Paranasal Sinuses, and Anterior Skull Base (PDFDrive)Document268 pagesEndoscopic Surgery of The Lateral Nasal Wall, Paranasal Sinuses, and Anterior Skull Base (PDFDrive)Butt KNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Anatomy EarDocument44 pagesAnatomy Earrinaldy agungNo ratings yet

- Scott Brown Vol 2 8thDocument1,527 pagesScott Brown Vol 2 8thshu Du100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Nasal Septal PerforationDocument12 pagesNasal Septal PerforationRini RahmawulandariNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Equine Respiratory Medicine and SurgeryDocument673 pagesEquine Respiratory Medicine and SurgeryRafael NicolauNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Surgical Treatment of Diseases of The Maxillary SinusDocument6 pagesSurgical Treatment of Diseases of The Maxillary SinusRaymund Niño BumatayNo ratings yet

- 1st BDS Oral Histology and Dental AnotomyDocument11 pages1st BDS Oral Histology and Dental AnotomyAmrutha Dasari100% (1)

- History of Paranasal Sinus SurgeryDocument8 pagesHistory of Paranasal Sinus SurgeryJassel DurdenNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Myology: The Buccinators Mechanism The TongueDocument33 pagesMyology: The Buccinators Mechanism The TongueJee Arceo100% (1)

- Crainial NervesDocument34 pagesCrainial Nervessamar yousif mohamedNo ratings yet

- Week 1Document4 pagesWeek 1nilaahanifahNo ratings yet

- Aj CSF - Rhinorrhea - + - Nasal - Foreign - Body - + - Myiasis - + - ChoanalDocument63 pagesAj CSF - Rhinorrhea - + - Nasal - Foreign - Body - + - Myiasis - + - ChoanalTradigrade PukarNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- OS - Key Points by Danesh PDFDocument16 pagesOS - Key Points by Danesh PDFNoor HaiderNo ratings yet

- Auditory PathwayDocument33 pagesAuditory PathwayAnusha Varanasi100% (1)

- How To Draw Anime & Game Characters Vol.Document152 pagesHow To Draw Anime & Game Characters Vol.Fernando Godoy100% (2)

- Aural RehabilitationDocument21 pagesAural RehabilitationSusan JackmanNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- sKuLL Positioning sTuDy GuiDe!!!Document6 pagessKuLL Positioning sTuDy GuiDe!!!Ling YuNo ratings yet

- Facial NerveDocument128 pagesFacial NervevaneetNo ratings yet

- 41 Emotions As Expressed Through Body LanguageDocument9 pages41 Emotions As Expressed Through Body LanguageSocaciu Gabriel100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)