Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 Territory Sign AJNR

Uploaded by

Abdul AzeezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 Territory Sign AJNR

Uploaded by

Abdul AzeezCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

ADULT BRAIN

Three-Territory DWI Acute Infarcts: Diagnostic Value

in Cancer-Associated Hypercoagulation Stroke

(Trousseau Syndrome)

X P.F. Finelli and X A. Nouh

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: DWI infarcts involving the bilateral anterior and posterior circulation suggest an embolic etiology. In the

absence of an identifiable embolic source, we analyzed DWI lesions involving these 3 cerebral territories to determine the diagnostic value

for ischemic infarction caused by cancer-associated hypercoagulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: A retrospective analysis of all brain MR imaging studies at our institution from July 2014 to June 2015 was

conducted, yielding 4075 studies. Of those, 17% (n ⫽ 709) contained the terms “restricted-diffusion” plus either “numerous,” “innumera-

ble,” “multiple,” or “bilateral.” Of these 709 reports, 6% (n ⫽ 41) of DWI lesions involving 3 or more vascular territories of the bilateral

anterior and posterior circulation were analyzed.

RESULTS: Of the 41 patients, 19 separate etiologies were identified, the most frequent being malignancy-related infarctions (22% [n ⫽ 9])

and hypoxic-ischemic injury (12% [n ⫽ 5]). Only 2 patients had an indeterminate etiology. The most frequent etiology of infarctions not

suspected clinically or radiographically was malignancy (P ⬍ .001). Infarctions of malignancy had a characteristic appearance, being

nonenhancing, nonring-appearing clusters or single areas of restricted diffusion of 0.5–2 cm with a peripheral location or larger vascular

territories, uncommonly in a watershed distribution, and with absence of diffuse cortical ribbon or deep gray nuclei involvement.

CONCLUSIONS: Approximately 1 in 5 ischemic infarcts in patients with DWI lesions involving 3 vessel territories are malignancy related.

In the absence of an identifiable embolic source, ischemic infarction with cancer-associated hypercoagulation accounts for 75% of cases.

Cancer-associated hypercoagulation infarction should be considered, particularly when no other cause is apparent.

ABBREVIATION: TS ⫽ Trousseau syndrome

U p to 15% of patients with malignancy may experience a

thromboembolic cerebrovascular event during their clinical

course.1 In addition, malignancy is frequently overlooked as a

ated with cancer, that includes various disorders probably involv-

ing multiple overlapping mechanisms. It has been suggested the

term “Trousseau syndrome” be restricted to unexplained throm-

cause of stroke and is commonly undiagnosed until a second botic events that either precede the diagnosis of an occult visceral

event occurs.2 Though the paraneoplastic hypercoagulable state is malignancy or appear concomitantly with the tumor.5 Cerebral

complex and not fully understood, it is an established mechanism infarction, mostly caused by in situ thrombosis in medium and

of thrombosis in malignancy. The importance of diagnosing can- small vessels, is thought to be related to the prothrombic state of

cer-associated hypercoagulation is appreciated because it may be TS. Verrucous endocarditises associated with cerebral emboli, in-

the heralding manifestation of occult malignancy. Treatment fection, or therapy-related strokes are alternative causes of isch-

with heparin has been demonstrated effective in preventing emic infarction.2,6 Given the familiar usage of TS by some authors

thrombotic events, including stroke.3,4 to refer to cancer-associated hypercoagulation,5 we use TS in that

Trousseau syndrome (TS) is a hypercoagulable state, associ-

context in this discussion.

DWI primarily defines ischemic infarcts in malignancy as

Received March 23, 2016; accepted after revision April 28.

small and involving multiple vessel territories,6-9 with the number

From the Department of Neurology, Hartford Hospital and University of Connect- of territories involved correlating with the likelihood of this syn-

icut School of Medicine, Hartford, Connecticut. drome.4,10-12 However, studies specifically evaluating MR imag-

Please address correspondence to Pasquale F. Finelli, MD, Department of Neurol-

ogy, Hartford Hospital and University of Connecticut School of Medicine, 80 Sey-

ing in cerebral infarction with TS and its diagnostic value in es-

mour St, Hartford, CT 06102-5037; e-mail: pasquale.finelli@hhchealth.org tablishing causality are lacking. Distinct from prior reports where

http://dx.doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4846 patient selection was based on the presence of stroke with malig-

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 37:2033–36 Nov 2016 www.ajnr.org 2033

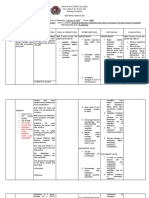

Etiologies of 3 territory diffusion-weighted lesions uated for radiographic appearance of

No. Clinical/MR Imaging, DWI, Enhancement Features DWI lesions. Lesions with MR charac-

Suspected etiology (n ⫽ 29) teristics of ischemic infarction (hyperin-

Trauma 1 History of trauma, imaging-associated sequelae of trauma, tense on DWI and restricting on ADC)

subarachnoid hemorrhage, shear pattern were deemed as infarction. The underly-

Demyelinating 1 Age, history of multiple sclerosis, periventricular/corpus

ing etiology was determined from a

callosum predilection

Hypoxic-ischemic 5 Hypotension, deep nuclei and cortical ribbon involvement chart review process. Lesion etiology

Metastasis 3 History of malignancy and/or ring or enhancing lesion was dichotomized into a “suspected” co-

Seizure 1 Seizures, deep nuclei and/or cortical ribbon enhancement hort (clinically suspected and docu-

HIV-related (n ⫽ 2) mented or suggested by MR imaging

Toxoplasmosis 1 HIV, periventricular, ring, enhancing, target sign, rarely

report) and a “not suspected” cohort

shows restricted diffusion

Fungal abscess 1 HIV, ring, enhancing, numerous restricted-diffusion lesions (clinically not suspected or documented

Cerebral emboli (n ⫽ 10) and/or not suggested by radiology re-

Endocarditis 4 Fever, leukocytosis, murmur, ring, enhancing port) during hospitalization. The “not

Air 1 Followed esophagogastroduodenoscopy suspected” cohort represents the pa-

Fat 1 Followed long bone fracture

tients in whom etiology was not sus-

Atrial fibrillation 2 No source other than atrial fibrillation found

Aortic atheroma 1 Significant arch atheroma noted pected by the treating physician or sug-

Aortic dissection 1 Patient had concomitant aortic dissection gested by the radiologist because of the

Postoperative (n ⫽ 6) clinical history given and reported radi-

Aneurysm coiling 1 Symptoms developed postoperatively ology reading.

Cardiac surgery 4 Symptoms developed postoperatively

Aortic aneurysm repair 1 Symptoms developed postoperatively RESULTS

Not suspected (n ⫽ 10)

Of 41 patients reviewed, a suspected eti-

Malignancy-related 9 Lung (n ⫽ 4), colon (n ⫽ 2), renal (n ⫽ 1), pancreas (n ⫽ 1),

bladder (n ⫽ 1) ology for 3-territory DWI lesions was

Intravascular lymphoma 1 Proven by brain biopsy identified in approximately 71% (n ⫽

Indeterminate (n ⫽ 2) 29), not suspected in approximately

Incomplete history 1 Lost to follow-up 24% (n ⫽ 10), and indeterminate in ap-

Multiple etiologies 1 Possible fat emboli vs Trousseau syndrome

proximately 5% (n ⫽ 2). A total of 19

separate etiologies were identified, in-

nancy or vice versa, our patient selection was based on the pres- cluding only 2 patients with indeterminate etiology. An embolic

ence of numerous, innumerable, multiple, or bilateral lesions on source, namely cardiac or large vessel, was the most common

MR imaging. At our institution, we have experienced many cases etiology in the “suspected” cohort. Of these 16 patients, only 1 had

of 3– cerebral territory infarctions associated with malignancy. concomitant systemic malignancy. In the “not suspected” cohort

However, the association of 3-territory DWI infarcts and malig- of 10 patients, 9 had a concomitant systemic malignancy and 1

nancy has not been studied. had intravascular lymphoma. In the absence of an identifiable

We speculate that selecting patients by using MR criteria al- embolic source, the presence of concomitant systemic malig-

lows for a more accurate assessment of diagnosing TS-related in- nancy was significantly associated with 3-territory DWI infarc-

farction compared with selection criteria using history of stroke tions (P ⬍ .001). The Table lists etiologies of all patients with

and cancer because the potential for error exists when cancer his- 3-territory DWI lesions with supporting clinical and radiographic

tory is overlooked or undiagnosed. In this study, we assessed the

features.

etiology of DWI-defined 3-territory infarcts, with attention to

Moreover, patients with underlying malignancy represented

their diagnostic value in TS-related stroke.

approximately 29% (n ⫽ 12) of all patients. In 9 patients, malig-

nancy as cause of stroke etiology was diagnosed in a retrospec-

MATERIALS AND METHODS

tive fashion after excluding all other potential causes and the

We sought to analyze the MR imaging characteristics of patients

concomitant presence of active malignancy. The mean age was

with DWI lesions involving 3 vascular territories (namely, the

bilateral anterior and the posterior circulation) and correlate 61 ⫾ 27 years and 66% were men. The malignancies in our

them with individual etiologies. A retrospective chart review at cohort included lung cancer (n ⫽ 4), colon cancer (n ⫽ 2), and

our institution was conducted after approval from the institu- 1 case each for renal, bladder, and pancreatic cancer. In only 2

tional review board for conducting research. All data on brain MR patients, cause was indeterminate because of incomplete his-

imaging conducted from July 1, 2014 to June 30, 2015 were in- tory or multiple possible etiologies. Although 1 patient with

cluded, encompassing 4075 studies with radiology reports. A 3-territory infarctions during hospitalization was diagnosed

search tool for the terms “restricted-diffusion” plus either “nu- with biopsy-proved intravascular lymphoma, it was not sus-

merous,” “innumerable,” “multiple,” or “bilateral” yielded 709 pected by the treating physician or suggested by radiology re-

studies. Of these studies, only reports with multiple DWI lesions port as the etiology.

that involved 3 vascular territories that included bilateral anterior In the “suspected” cohort, 3 patients had known metastatic

and posterior circulation were analyzed. After exclusion, only 41 cancer with 3-territory DWI involvement. However, lesions were

studies met criteria for analysis. Studies were reviewed and eval- ring-enhancing and suggestive of metastatic tumor spread to

2034 Finelli Nov 2016 www.ajnr.org

DISCUSSION

DWI infarction in multiple territories

has been reported,4,10-12 including

3-territory lesions,4,10 yet a clear expres-

sion of the diagnostic significance of this

MR imaging pattern with TS-related in-

farction has not been articulated. In our

study, among the 12 patients without a

suspected etiology, malignancy-related

ischemic events were the source in 9

(75%). Though not unique, the diffu-

sion-weighted MR imaging features in

our patients with malignancy-related in-

farction were highly suggestive.

In a prospective study evaluating

embolic signals detected by transcranial

Doppler in 74 patients with malignancy-

related infarction, embolic signals were

more commonly seen in patients lacking

conventional stroke risk factors (P ⫽

.034) and were correlated strongly with

D-dimer levels and the number of em-

bolic signals detected (P ⫽ ⬍ .001).13

The excess of embolic signal in patients

with malignancy may explain the 3-ter-

ritory DWI pattern observed or support

this hypothesis, though this cannot ex-

clude the possibility of intrinsic medi-

um- and small-vessel thrombosis.

DWI lesions in our patient cohort

also manifested diffuse changes that in-

volve deep gray nuclei and/or cortical

ribbon as seen with hypoxia-ischemia

and seizure, whereas ring lesions, with

or without enhancement, were associ-

ated with infection, metastasis, and en-

docarditis. Only endocarditis was asso-

ciated with a peripheral predilection.

TS-related infarction in the context of

3-territory DWI infarcts without an

identifiable cause was not considered by

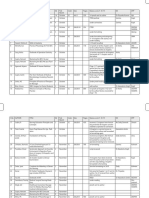

FIGURE. DWI infarcts involving bilateral anterior and posterior circulation (3 territory) with TS in

the clinician or radiologist in our pa-

9 study group patients.

tients. Furthermore, in the presence of

both malignancy and atrial fibrillation,

the brain. Other causes of 3-territory DWI lesions not defined if echocardiogram shows no valvular pathology or intracardiac

as ischemic infarctions included infection, demyelination, sei- clot, TS should be a leading consideration. A tranesophageal

zure, and trauma. In the suspected cohort, an established em- echocardiogram is necessary to exclude a cardioembolic source.

bolic source was found in 10 patients and occurred postoper- In our study, we sought to evaluate the role of MR imaging in

atively in 6 patients. Though the 3-territory pattern is the most aiding with the diagnostic approach to multiple territory infarc-

compelling MR imaging feature of malignancy-related isch- tions. Therefore, our approach was notably based on MR imaging

emic infarctions, characteristic radiographic DWI findings for as the identifying feature. We acknowledge that because of the

malignancy-related infarction are often noted. These include retrospective nature of the study, linking the etiology of the 3-ter-

nonenhancing, nonring clusters or single areas of restricted ritory infarctions to malignancy is speculative based on excluding

diffusion of 0.5–2 cm with a peripheral preference or large other causes as documented by the work-up completed by the

vascular territories, uncommonly in a watershed distribution, treating physician. Moreover, it is possible that patients with true

with absence of diffuse cortical ribbon or deep gray involve- malignancy-related infarctions or TS involving only 1 or 2 terri-

ment (Figure). tories were not accounted for in this study. Longitudinal data,

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 37:2033–36 Nov 2016 www.ajnr.org 2035

such as prolonged cardiac monitoring to evaluate the possibility proportion of patients with 3-territory infarctions versus other

of atrial fibrillation in patients where etiology was not diagnosed MR patterns.

during hospitalization, were not available. However, a substantial

work-up was completed during hospitalization as 19 separate eti-

ologies were identified. REFERENCES

Elevated D-dimer level, a direct measure of activated coagula- 1. Graus F, Rogers LR, Posner JB. Cerebrovascular complications in

tion, is associated with malignancy and has been used as a measure patients with cancer. Medicine 1985;64:16 –35 CrossRef Medline

2. Taccone FS, Jeangette SM, Blecic SA. First-ever stroke as initial pre-

of hypercoagulability in studies investigating stroke and malig-

sentation of systemic cancer. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;17:

nancy.6,7 However, this biomarker is not specific to the hyperco- 169 –74 CrossRef Medline

agulable status of malignancy and can be elevated in several other 3. Murinello A, Guedes P, Rocha G, et al. Trousseau’s syndrome due to

conditions, such as infection, venous thromboembolism, and asymptomatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. GE Port J Gastroenterol

stroke.14 D-dimer levels were not reported in our study because of 2013;20:172–76 CrossRef

4. Kwon HM, Kang BS, Yoon BW. Stroke as the first manifestation of

the few patients who had these levels tested during hospitaliza-

concealed cancer. J Neurol Sci 2007;258:80 – 83 CrossRef Medline

tion. However, the aim of this study was to highlight the diagnos- 5. Varki A. Trousseau’s syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple

tic value of the 3-territory DWI pattern as an additional diagnostic mechanisms. Blood 2007;110:1723–29 CrossRef Medline

tool in the stroke work-up. In addition, because of the few patients 6. Grisold W, Oberndorfer S, Struhal W. Stroke and cancer: a review.

in this study and the lack of patients with active malignancy and Acta Neurol Scand 2009;119:1–16 CrossRef Medline

7. Kim SG, Hong JM, Kim HY, et al. Ischemic stroke in cancer patients

stroke of undetermined etiology involving 1 or 2 territories, the

with and without conventional mechanisms: a multicenter study in

positive or negative predictive value of 3-territory DWI infarcts Korea. Stroke 2010;41:798 – 801 CrossRef Medline

could not be calculated. 8. Schwarzbach CJ, Schaefer A, Ebert A, et al. Stroke and cancer: the

importance of cancer-associated hypercoagulation as a possible

CONCLUSIONS stroke etiology. Stroke 2012;43:3029 –34 CrossRef Medline

9. Chen Y, Zeng J, Xie X, et al. Clinical features of systemic cancer

DWI infarcts involving 3 specific vascular territories, in the ab-

patients with acute cerebral infarction and its underlying patho-

sence of an identifiable embolic source or other disease associated genesis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:4455– 63 Medline

with such lesions, are highly suggestive of cancer-associated hy- 10. Kim SJ, Park JH, Lee MJ, et al. Clues to occult cancer in patients with

percoagulation stroke. Because TS-related stroke may be the her- ischemic stroke. PLoS One 2012;7:e44959 CrossRef Medline

alding manifestation of an occult malignancy, work-up should 11. Bang OY, Seok JM, Kim SG, et al. Ischemic stroke and cancer: stroke

include D-dimer and fibrinogen levels; tumor biomarkers; severely impacts cancer patients, while cancer increases the num-

ber of strokes. J Clin Neurol 2011;7:53–59 CrossRef Medline

screening for deep vein thrombosis; CT of chest, abdomen, and 12. Hong CT, Tsai LK, Jeng JS. Patterns of acute cerebral infarcts in

pelvis; and PET scan when other tests are negative. Given the patients with active malignancy using diffusion-weighted imaging.

efficacy of heparin in preventing thrombotic events in cancer- Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;28:411–16 CrossRef Medline

associated hypercoagulation, timely diagnosis is paramount. As 13. Seok JM, Kim SG, Kim JW, et al. Coagulopathy and embolic signal in

described here, the 3-territory DWI infarct pattern can provide an cancer patients with ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol 2010;68:213–19

CrossRef Medline

important diagnostic clue to an otherwise underrecognized cause 14. Lippi G, Bonfanti L, Saccenti C, et al. Causes of elevated D-dimer in

of stroke. Future prospective studies evaluating patients with ma- patients admitted to a large urban emergency department. Eur J In-

lignancy-related infarction with TS are needed to quantify the tern Med 2014;25:45– 48 CrossRef Medline

2036 Finelli Nov 2016 www.ajnr.org

You might also like

- Advances in Intracranial HemorrhageDocument15 pagesAdvances in Intracranial HemorrhageJorge GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Familial Intracranial Aneurysms Screening GuidelinesDocument6 pagesFamilial Intracranial Aneurysms Screening GuidelinesReskiyani AsharNo ratings yet

- Identification of Embolic Stroke Patterns by Diffusion-Weighted MRI in Clinically Defined Lacunar Stroke SyndromesDocument5 pagesIdentification of Embolic Stroke Patterns by Diffusion-Weighted MRI in Clinically Defined Lacunar Stroke SyndromescathyafaNo ratings yet

- Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.6Document19 pagesAneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.6Aldy Setiawan PutraNo ratings yet

- Hassell (2013) - Silent Cerebral Infarcts Associated With Cardiac Disease and ProceduresDocument11 pagesHassell (2013) - Silent Cerebral Infarcts Associated With Cardiac Disease and ProceduresVanessaNo ratings yet

- 2017 HSA Clinical PracticeDocument10 pages2017 HSA Clinical PracticeAndrea MartinezNo ratings yet

- Cryptogenic Stroke: Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesCryptogenic Stroke: Clinical PracticenellieauthorNo ratings yet

- Intracranial Hemorrhage With Cerebral Venous Sinus ThrombosisDocument2 pagesIntracranial Hemorrhage With Cerebral Venous Sinus ThrombosisNeurologia homicNo ratings yet

- Cavernomas of the CNS: Basic Science to Clinical PracticeFrom EverandCavernomas of the CNS: Basic Science to Clinical PracticeOndřej BradáčNo ratings yet

- Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: Robert D. Brown, JR., M.D., M.P.HDocument8 pagesUnruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: Robert D. Brown, JR., M.D., M.P.HtonnyprogramadorNo ratings yet

- Atrial Myxoma As A Cause of Stroke: Case Report and DiscussionDocument4 pagesAtrial Myxoma As A Cause of Stroke: Case Report and DiscussionNaveedNo ratings yet

- Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument10 pagesSubarachnoid HemorrhageRoberto López Mata100% (1)

- 1 Abses SerebelumDocument6 pages1 Abses SerebelumseruniallisaaslimNo ratings yet

- Three Territory Sign NEURCLINPRACTDocument5 pagesThree Territory Sign NEURCLINPRACTAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Cryptogenic Stroke 2016Document10 pagesCryptogenic Stroke 2016tatukyNo ratings yet

- Yes This Is A TitleDocument8 pagesYes This Is A TitleIzzHyukNo ratings yet

- Brain Strokes Related To Aortic Aneurysma - The Analysis of Three CasesDocument4 pagesBrain Strokes Related To Aortic Aneurysma - The Analysis of Three Casesdian asrianaNo ratings yet

- Brain Arteriovenous MalformationsDocument20 pagesBrain Arteriovenous MalformationsTony NgNo ratings yet

- Hemorragia SubaracnoideaDocument10 pagesHemorragia SubaracnoideaAna TeresaNo ratings yet

- BCR 2012 007205Document4 pagesBCR 2012 007205shofidhiaaaNo ratings yet

- Int J Stroke 2014 Benavente 1057 64Document8 pagesInt J Stroke 2014 Benavente 1057 64Fauzan IndraNo ratings yet

- Shaabi2014 PDFDocument3 pagesShaabi2014 PDFIgor PiresNo ratings yet

- Mks 054Document7 pagesMks 054Mirela CiobanescuNo ratings yet

- Thick and Diffuse Cisternal Clot Independently Predicts Vasospasm-Related Morbidity and Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument9 pagesThick and Diffuse Cisternal Clot Independently Predicts Vasospasm-Related Morbidity and Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageVanessa LandaNo ratings yet

- tmp253C TMPDocument10 pagestmp253C TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Artery of Percheron Infarct: An Acute Diagnostic Challenge With A Spectrum of Clinical PresentationsDocument9 pagesArtery of Percheron Infarct: An Acute Diagnostic Challenge With A Spectrum of Clinical PresentationsMaria JimenezNo ratings yet

- Different Clinical Phenotypes of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source: A Subgroup Analysis of 86 PatientsDocument9 pagesDifferent Clinical Phenotypes of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source: A Subgroup Analysis of 86 PatientsSuryati HusinNo ratings yet

- Presentation Other Than Major Rupture - GreenbergDocument13 pagesPresentation Other Than Major Rupture - GreenbergAlexandra CNo ratings yet

- 125-Article Text-375-1-10-20180214 PDFDocument5 pages125-Article Text-375-1-10-20180214 PDFsivadeavNo ratings yet

- Large Cerebral Arachnoid CystDocument2 pagesLarge Cerebral Arachnoid CystAtiquzzaman RinkuNo ratings yet

- 10.1136@neurintsurg 2019 015375 PDFDocument5 pages10.1136@neurintsurg 2019 015375 PDFDito WadhikoNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection With Clinical Presentation of Acute Myocardial InfarctionDocument3 pagesSpontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection With Clinical Presentation of Acute Myocardial InfarctionSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Relevance of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts in Vascular Cognitive ImpairmentDocument10 pagesClinical Relevance of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts in Vascular Cognitive Impairmentzefri suhendarNo ratings yet

- NHL CT FindingDocument7 pagesNHL CT FindingDwi Utari PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Deep Venous Thrombosis Diferential DiagnosisDocument8 pagesDeep Venous Thrombosis Diferential DiagnosisBeby Dwi Lestari BajryNo ratings yet

- Full StrokeDocument9 pagesFull StrokeHervia agshaNo ratings yet

- Seizure After StrokeDocument6 pagesSeizure After StrokenellieauthorNo ratings yet

- Mayoclinproc 85-5-004Document6 pagesMayoclinproc 85-5-004Alain SánchezNo ratings yet

- 080508-148 Syphilitc Aneurys Case Report PDFDocument4 pages080508-148 Syphilitc Aneurys Case Report PDFCarol SantosNo ratings yet

- Brainsci 10 00538Document12 pagesBrainsci 10 00538Charles MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Contemporary ManagementFrom EverandExtracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Contemporary ManagementNo ratings yet

- Susac SindromeDocument10 pagesSusac SindromeOTTO JESUS VEGA VEGANo ratings yet

- The Management of Intracranial AbscessesDocument3 pagesThe Management of Intracranial AbscessesDio AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Tto VasoespasmoDocument6 pagesTto VasoespasmoHernando CastrillónNo ratings yet

- STR 0000000000000418Document13 pagesSTR 0000000000000418Nelson Da VegaNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Morris Et Al-AnnotatedDocument7 pages2017 - Morris Et Al-AnnotatedCemal GürselNo ratings yet

- VasospasmDocument7 pagesVasospasmmlannesNo ratings yet

- Carotid UltrasoundDocument9 pagesCarotid UltrasoundLora LefterovaNo ratings yet

- 2011-Calviere-Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm As A Cause of Cerebral IschemiaDocument6 pages2011-Calviere-Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm As A Cause of Cerebral IschemiaHaris GiannadakisNo ratings yet

- Acv PDFDocument14 pagesAcv PDFFelipe AlcainoNo ratings yet

- Conclusion: Long-Term Follow-Up ForDocument31 pagesConclusion: Long-Term Follow-Up ForHima HuNo ratings yet

- Comment: Vs 1 7% of 261 Patients With Atrial TachyarrhythmiasDocument2 pagesComment: Vs 1 7% of 261 Patients With Atrial TachyarrhythmiasDewina Dyani Rosari IINo ratings yet

- Stroke NarrativeDocument10 pagesStroke Narrativecfalcon.medicinaNo ratings yet

- Jhua16000143 PDFDocument3 pagesJhua16000143 PDFsamiratumananNo ratings yet

- Noc110069 346 351Document6 pagesNoc110069 346 351Carlos AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Ajiboye 2015Document11 pagesAjiboye 2015editingjuryNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous ThrombosisDocument14 pagesCerebral Venous ThrombosisSrinivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument3 pagesReportbagas rachmadiNo ratings yet

- InvestigationsDocument28 pagesInvestigationsAndrei BulgariuNo ratings yet

- mcnally-MRIclinical-of Stroke-In-PatientsDocument8 pagesmcnally-MRIclinical-of Stroke-In-PatientsAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Fibromuscular Dysplasia and Cervical Artery DissectionDocument9 pagesFibromuscular Dysplasia and Cervical Artery DissectionAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Features of Covid Related StrokeDocument10 pagesFeatures of Covid Related StrokeAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Protocolized NatriuresiDocument10 pagesProtocolized NatriuresiAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Stroke in CovidDocument13 pagesStroke in CovidAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- PRES Radiology Part 1Document7 pagesPRES Radiology Part 1Abdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Voll Muth 2019Document7 pagesVoll Muth 2019LUIS ENRIQUE CORTEZ SALAZARNo ratings yet

- Central Variant PRESDocument5 pagesCentral Variant PRESAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Adult Brain Hemorrhagic PRES Linked to COVIDDocument4 pagesAdult Brain Hemorrhagic PRES Linked to COVIDAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- 2015 PMR GuidelinesDocument12 pages2015 PMR GuidelinesMercedes Paola Dehesa IsidoroNo ratings yet

- Disting Imaging Patterns of PRESDocument8 pagesDisting Imaging Patterns of PRESAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- PRES Radiology Part 1Document7 pagesPRES Radiology Part 1Abdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Igg 4Document12 pagesIgg 4aydabogoniNo ratings yet

- Three Territory Sign NEURCLINPRACTDocument5 pagesThree Territory Sign NEURCLINPRACTAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Annalsats 201503-181cc PDFDocument3 pagesAnnalsats 201503-181cc PDFAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Definition of Good Standing PDFDocument1 pageDefinition of Good Standing PDFAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- List of Participating Airport Lounges : S.No Lounge State City TerminalDocument4 pagesList of Participating Airport Lounges : S.No Lounge State City TerminalSaahil ShahNo ratings yet

- Infarcts in MigraineDocument10 pagesInfarcts in MigraineAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Papilloedema GradingDocument7 pagesPapilloedema GradingAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Association of Vertigo and MigraineDocument6 pagesAssociation of Vertigo and MigraineAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia After Stroke and Its ManagementDocument2 pagesDysphagia After Stroke and Its ManagementAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Choosing Wisely - American Headache SocietyDocument2 pagesChoosing Wisely - American Headache SocietyAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Update On CNS Pathology-Dubai 2015Document82 pagesUpdate On CNS Pathology-Dubai 2015Abdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Neuro Ophthalmology 2011 SyllabusDocument65 pagesNeuro Ophthalmology 2011 SyllabusAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Papilloedema Grading Guide: Frisel's Scale ExplainedDocument7 pagesPapilloedema Grading Guide: Frisel's Scale ExplainedAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Association of Vertigo and MigraineDocument6 pagesAssociation of Vertigo and MigraineAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Intracranial Dural Arteriovenous Fistulae: Presentation and Natural History ClassificationDocument3 pagesIntracranial Dural Arteriovenous Fistulae: Presentation and Natural History ClassificationFinger JempolNo ratings yet

- Samsung Galaxy s2 - User GuideDocument164 pagesSamsung Galaxy s2 - User GuideMindfk GsNo ratings yet

- Samsung Galaxy S II (GT-I9100) Quick Start Guide (Rev.1.3)Document26 pagesSamsung Galaxy S II (GT-I9100) Quick Start Guide (Rev.1.3)mixer5056No ratings yet

- Lee Meningiomas PDFDocument615 pagesLee Meningiomas PDFVineesh VargheseNo ratings yet

- Teenage Pregnancy Brief DiscussionDocument3 pagesTeenage Pregnancy Brief DiscussionJoanna Peroz100% (1)

- UrgotulDocument2 pagesUrgotulBassem Khalid YasseenNo ratings yet

- Classic Laryngeal Mask Airway Insertion With Laryngoscope Mcgrath and Macintosh: A Case SeriesDocument3 pagesClassic Laryngeal Mask Airway Insertion With Laryngoscope Mcgrath and Macintosh: A Case SeriesYeyen AgustinNo ratings yet

- IUD Contraception in Dogs TestedDocument4 pagesIUD Contraception in Dogs TestedAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Community Medicine MnemonicsDocument27 pagesCommunity Medicine MnemonicsIzaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy DAP Note Focuses on Substance AbuseDocument2 pagesPsychotherapy DAP Note Focuses on Substance AbuseMistor Williams100% (1)

- Cornea PDFDocument465 pagesCornea PDFputraNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Cancer PDFDocument461 pagesEncyclopedia of Cancer PDFBachtiar Muhammad ArifNo ratings yet

- Different Types of Medicines ExplainedDocument3 pagesDifferent Types of Medicines ExplainedAngelique BernardinoNo ratings yet

- Vmax Standard ProtocolDocument5 pagesVmax Standard ProtocolCheeken Charli0% (1)

- Cornish Immunization Waiver PolicyDocument2 pagesCornish Immunization Waiver PolicyDonnaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 19 - Infective Is Pericarditis and MyocarditisDocument4 pagesLecture 19 - Infective Is Pericarditis and MyocarditisJane HoNo ratings yet

- Placenta Previa GuideDocument7 pagesPlacenta Previa GuideMargaret AssilasNo ratings yet

- Folliculitis Decalvans Update July 2019 - Lay Reviewed July 2019Document4 pagesFolliculitis Decalvans Update July 2019 - Lay Reviewed July 2019sjeyarajah21No ratings yet

- Kimia Farma Per 30 September ZRMM076Document271 pagesKimia Farma Per 30 September ZRMM076SriyatiNo ratings yet

- Yukgehnaish Etal PhageLeadsDocument16 pagesYukgehnaish Etal PhageLeadsAugust ThomasenNo ratings yet

- Types of Medications Used After SurgeryDocument9 pagesTypes of Medications Used After SurgeryRegine VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- NCP - Ineffective Breathing PatternDocument4 pagesNCP - Ineffective Breathing PatternPRINCESS KOBAYASHINo ratings yet

- Fasting Glucose Vs A1CDocument1 pageFasting Glucose Vs A1CBrent HussongNo ratings yet

- 2010 Catalog USDocument47 pages2010 Catalog USengequinNo ratings yet

- Breathing Exercise of ScoliosisDocument3 pagesBreathing Exercise of Scoliosisrima rizky nourliaNo ratings yet

- Study On Emergence of MDR Pathogen and Its Microbiological StudyDocument9 pagesStudy On Emergence of MDR Pathogen and Its Microbiological StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Infertility Questionnaire A. General InformationDocument4 pagesInfertility Questionnaire A. General InformationYogita DansenaNo ratings yet

- (OSCE) 3.0 Cardiovascular ExaminationDocument5 pages(OSCE) 3.0 Cardiovascular ExaminationJara RogacionNo ratings yet

- Comparison of ICD-10 and DSM-IV Criteria For Postconcussion SyndromedisorderDocument19 pagesComparison of ICD-10 and DSM-IV Criteria For Postconcussion Syndromedisorderneoraymix blackNo ratings yet

- A Model To Predict Short-Term Death or Readmission After Intensive Care Unit DischargeDocument10 pagesA Model To Predict Short-Term Death or Readmission After Intensive Care Unit DischargeInnani Wildania HusnaNo ratings yet

- ST 11 Juni-1Document38 pagesST 11 Juni-1yunannegariNo ratings yet

- Untitled 5 PDFDocument6 pagesUntitled 5 PDFDeepak saxenaNo ratings yet

- Osseointegration Short Review PDFDocument5 pagesOsseointegration Short Review PDFkryptonites1234No ratings yet