Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Imperialism As The Last Stage of Capitalism

Uploaded by

Atri Deb ChowdhuryOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Imperialism As The Last Stage of Capitalism

Uploaded by

Atri Deb ChowdhuryCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter Title: Imperialism as the Last Stage of Capitalism

Book Title: On the Formation of Marxism

Book Subtitle: Karl Kautsky’s Theory of Capitalism, the Marxism of the Second

International and Karl Marx’s Critique of Political Economy

Book Author(s): Jukka Gronow

Published by: Brill

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h23p.13

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0

International License (CC BY-NC 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to On the Formation

of Marxism

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

chapter 9

Imperialism as the Last Stage of Capitalism

Ever since the publication of Kautsky’s main writings on imperialism, he has

been criticised for his characterisation of imperialism as only one possible

alternative to the future development of capitalism. An early and perhaps the

best-known critique came from Lenin, who criticised Kautsky for his exclus-

ively political definition of imperialism. In this respect, one can agree with John

H. Kautsky’s interpretation of Karl Kautsky’s theory of imperialism as presented

in his article on Schumpeter and Kautsky:

Whether Kautsky inclined to the Schumpeterian ‘pre-industrial’ or the

Hilferdingian ‘industrial’ explanation of imperialism certain elements of

his thought remained constant; it was banking capital rather than indus-

trial capital in its pure form that was a driving force, if not the driving

force, of imperialism … and finally, imperialism was merely one possible

form of the general and inevitable phenomenon of industrial expansion-

ism into agrarian areas and hence was not necessary to capitalism.1

The same argument was presented even more forcefully by Rainer Kraus:

Since the 1880s, the essential feature of Kautsky’s theory of imperialism

consisted in attempting to demonstrate the groundlessness of virtually

all arguments in favour of colonial expansion, in as far as these arguments

were prejudiced by the view that colonies were necessary for the survival

of capitalist society.2

Even though Kautsky did not simply think of imperialism as being an atavism

in capitalism caused by pre-capitalist remnants in society, and even though

Kautsky’s theory is not in this respect identical to that of J.A. Hobson, Joseph

Schumpeter and Emil Lederer, as claimed by Gottschalch,3 it is true that Kaut-

sky understood imperialism as being more of an exception in the normal devel-

opment of capitalism. Or rather, imperialism is both a permanent problem

1 John H. Kautsky 1961, p. 118.

2 Kraus 1978, p. 171.

3 Gottschalch 1962, p. 89.

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/9789004306653_011

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

imperialism as the last stage of capitalism 127

caused by the unequal development of industrial and agrarian production and

a politically avoidable problem to be eliminated as soon as the power of finance

capital could be eliminated.

As stated earlier, Kautsky’s conception of imperialism resembled that of

Lenin’s in many respects. To both of them, imperialism is a consequence of

the centralisation and monopolisation of capital and the formation of cartels

and trusts. Furthermore, the centralisation of capital is a necessary feature

of capitalism. Another characteristic feature of imperialism is the power and

domination of finance capital over industrial capital, and the importance of

the export of capital compared with the export of commodities. Kautsky’s

emphasis on the role of protective tariffs did not, on the other hand, figure in

Lenin’s analysis – a fact already indicating that Kautsky, more so than Lenin,

analysed imperialism as a concrete historical form of the economic policy of

the state. Neither did the idea of the difference and conflict between agrarian

and industrial countries and production explain the annexation of colonies

and their economic importance to Lenin – even though it was also mentioned

by Lenin. For Kautsky, this difference was the most important single cause of

imperialistic policy. The main and decisive difference, however, is that whilst

Kautsky understood imperialism as a specific political method of guaranteeing

the profits of capital, Lenin also considered imperialism as being a specific and

necessary stage in the economic development of capitalism.

To Lenin, the future of capitalism was by nature necessarily violent; it rep-

resented the repression of the people and led to the stagnation of productive

forces and repressive methods of government. In the analysis of imperialism

of both Kautsky and Lenin, there was, however, one more important common

characteristic: power is the new decisive factor in imperialism, and relations

of power and dominance replace relations of a purely economic character in

imperialism.

In defining imperialism as the monopolistic phase of capitalism, Lenin did

not yet differ essentially from Kautsky’s analysis. Neither Kautsky nor Lenin dis-

cussed in any great detail the nature of the transformation of free competition

into monopolistic competition. They simply stated that monopolistic compet-

ition – to a certain extent – takes the place of free competition and that this

transformation is made possible by the centralisation of capital – at least in

the internal market. It must nevertheless be admitted that Lenin discussed

the relation between free competition and monopolistic competition in more

detail than Kautsky. To Kautsky, the monopolistic organisations were simply

the most influential power organisations in a society realising their interests in

state policy. Kautsky did not formulate any explicit conception of competition

in capitalism.

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

128 chapter 9

According to Lenin, monopoly is the economic essence of imperialism.

However, this definition must be complemented by a list of other defining

characteristics of imperialism:

And so … we must give a definition of imperialism that will include the

following five of its basic features: 1) the concentration of production and

capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies

which play a decisive role in economic life; 2) the merging of bank capital

with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this ‘finance

capital’, of a financial oligarchy; 3) the export of capital as distinguished

from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance; 4) the

formation of international monopolist capitalist associations which share

the world among themselves; and 5) the territorial division of the whole

world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed.4

Having presented the above list, Lenin was ready to formulate a ‘more com-

plete’ definition of imperialism:

Imperialism is capitalism at the stage of development at which the dom-

inance of monopolies and finance capital is established; in which the

export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the divi-

sion of the world among the international trusts has begun, in which the

division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalists has

been completed.5

Immediately after presenting his own ‘definition’ of imperialism, Lenin criti-

cised Kautsky’s conception. According to Lenin, Kautsky made two grave mis-

takes in his analysis of imperialism. To begin with, Kautsky’s conception of

imperialism was restricted to a certain specific political method of capitalist

states. The second mistake was that Kautsky emphasised imperialism as being

equivalent to the method of annexation of colonies. Kautsky’s definition of

imperialism as a specific political form or method of capitalist states was as

such correct but, in Lenin’s opinion, incomplete. Kautsky forgot that imperi-

alism is essentially reactionary and violent by nature. At least in this respect

Lenin’s critique of Kautsky was, however, misdirected. On several occasions,

Kautsky stated explicitly that imperialism is reactionary and violent in char-

4 Lenin 1967d, pp. 745–6.

5 Lenin 1967d, p. 746.

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

imperialism as the last stage of capitalism 129

acter. Lenin’s critique of the economic causes of imperialism as formulated

by Kautsky was, however, more adequate. According to Lenin, Kautsky was

mistaken in indentifying the causes of imperialism with the complex and prob-

lematic relation between industrial and agrarian capital. Imperialism cannot

be adequately characterised as representing the interests of industrial capital

in enlarging the market for its products; the dominating form of capital in

imperialism is finance capital. Furthermore, the annexation of agrarian areas or

countries as colonies of industrial states is not as such typical only of imperial-

ism. Imperialism is, on the contrary, characterised by the struggle for hegemony

over industrial countries as well.6

Kautsky’s main failure in analysing imperialism, however, was that in dis-

tinguishing between political and economic factors in imperialism, he claimed

that there is possibly another kind of policy in modern capitalism which would

satisfy the interests of industrial capital, as well as imperialism, and which

would not be violent and reactionary in character.7 Lenin’s conclusion in his

critical analysis of Kautsky’s conception of imperialism was that Kautsky had

become a reformist and an enemy of Marxism:

The result is a slurring over and a blunting of the most profound contra-

dictions of the latest stage of capitalism, instead of an exposure of their

depth; the result is bourgeois reformism instead of Marxism.8

The main target of Lenin’s critique was Kautsky’s concept of ultra-imperialism.

Lenin admitted in principle that the economic development of capitalism

would lead to the formation of a single worldwide trust. On one occasion, Lenin

even referred to the possible formation of a super-monopoly.9 But such a proph-

ecy would be totally devoid of any interest.10 Compared with the actual devel-

opment of the world economy at the beginning of the century, the conception

of ultra-imperialism could be shown to contradict the actual state of affairs.

Kautsky’s conception was, after all, dangerous. It lent support to the legitima-

tion of imperialism in emphasising the possibility of a non-contradictory devel-

opment of capitalism. According to Kautsky, capitalism can develop without

crises; in reality, imperialism sharpens these contradictions and increases the

occurrence of crises in capitalism:

6 Lenin 1967d, pp. 746–8.

7 Lenin 1967d, p. 748.

8 Lenin 1967d, pp. 748–9.

9 Lenin 1967d, p. 728.

10 Lenin 1967d, p. 750.

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

130 chapter 9

Are not the international cartels which Kautsky imagines are the embryos

of ‘ultra-imperialism’ … an example of the division and the redivision of

the world, the transition from peaceful division to non-peaceful division

and vice versa?11

And further:

Finance capital and the trusts do not diminish but increase the differ-

ences in the rate of growth of the various parts of the world economy.

Once the relation of forces is changed, what other solution of the con-

tradictions can be found under capitalism than that of force?12

As Lenin stated, it is exactly the characterisation of imperialism as only one spe-

cific and possible form of the politics of a capitalist state that does not pay any

attention to the fact that imperialism is a necessary consequence of the devel-

opment of capitalism which marks the main difference between their concep-

tions.13 Lenin did not approve of Kautsky’s ‘deduction’ of imperialism from

the different conditions of industrial and agrarian production. On the other

hand, he did not pay attention to the fact that Kautsky repeatedly mentioned

both monopolisation and the dominance of finance capital as the main causes

of imperialism too. The main target of his critique was quite obviously and

repeatedly not so much the fact that Kautsky did not understand the economic

‘essence’ of imperialism (imperialism as monopolistic capitalism). Kautsky was

to be criticised mainly because his analysis led to the dangerous conclusion that

imperialism can develop into a new stage of peaceful and non-aggressive cap-

italism. It is exactly this conclusion that made Kautsky’s conception essentially

a reformist one, to be criticised as such.14

11 Lenin 1967d, pp. 751–2.

12 Lenin 1967d, p. 752.

13 This major difference in the interpretations of the essential nature of imperialism was

already explicitly formulated by Karl Radek in the article ‘Our Struggle Against Imperial-

ism’ [‘Zum unseren Kampf gegen den lmperialismus’]: ‘The foundation of all the differ-

ences in our relationship to imperialism is the question of its character. What is imper-

ialism, and what is its relationship to capitalist development in general and to world-

economic expansion in particular? Is it the foreign policy of crashing capitalism, or simply

one of the forms still possible for capitalist display of power?’ (Radek 2011, p. 543). Radek’s

own answer to the question is obvious: ‘Imperialism is the only possible world policy of

the present capitalist era’ (Radek 2011, p. 549).

14 For a modern Marxist-Leninist evaluation of the elements of both genuine Marxism

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

imperialism as the last stage of capitalism 131

On the other hand, there is, in fact, not such a big difference between Lenin

and Kautsky in their evaluations of the consequences of imperialism for the

future of capitalism. According to both of them, imperialism leads to the applic-

ation of violent methods in politics and militarism at home and in foreign rela-

tions. In Lenin’s opinion: ‘domination, and the violence that is associated with

it, such are the relationships that are typical of the “latest phase of capitalist

development”’.15 Democratic methods of government are displaced by repress-

ive and reactionary ones; economic competition as the regulatory principle of

capitalism is displaced by the power and dominance of finance capital. Imper-

ialism further leads to the stagnation of productive forces and the sharpening

of crisis development both internationally and nationally. Lenin’s conception

of the consequences of imperialism for the economic progress of capitalism

did not markedly differ from Kautsky’s corresponding formulations. Kautsky

would accept all the conclusions drawn by Lenin too:

As we have seen, the deepest economic foundation of imperialism is

monopoly. This is capitalist monopoly, i.e. monopoly which has grown out

of capitalism and which exists in the general environment of capitalism,

commodity production and competition, in permanent and insoluble

contradiction to this general environment. Nevertheless, like all mono-

poly, it inevitably engenders a tendency of stagnation and decay. Since

monopoly prices are established, even temporarily, the motive cause of

technical and, consequently, of all other progress disappears to a certain

extent and, further, the economic possibility arises of deliberately retard-

ing technical progress.16

However, Kautsky’s most serious mistake – according to Lenin – was in ima-

gining that capitalism would develop more rapidly and more effectively if free

competition were re-established and it were not restricted by monopolies or

finance capital. Lenin claimed that even though it might be presupposed that

capitalism would develop more rapidly under the conditions of free compet-

ition, this presupposition is completely abstract. Kautsky forgot that the very

development of capitalism necessarily gives rise to the permanent monopol-

isation and centralisation of capital:

(read: Marxism-Leninism) and revisionism in Kautsky’s thinking about imperialism, see

Braionovich 1982, pp. 181–8; see also Braionovich 1979, pp. 208–19.

15 Lenin 1967d, p. 694.

16 Lenin 1967d, p. 754.

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

132 chapter 9

And monopolies have already arisen – precisely out of free competition!

Even if monopolies have now begun to retard progress, it is not an argu-

ment in favour of free competition, which has become impossible after it

has given rise to monopoly.17

In other words, Kautsky did not understand that the process of monopolisation

is an unavoidable result of capitalist development and as such an irreversible

process. And because of this mistake, Kautsky became a reactionary and a

reformist.18

In Lenin’s analysis, imperialism was not only the necessary consequence of

capitalist development, it was also the immediate predecessor of socialism.

There is no other alternative to imperialism but socialism, and on the other

hand, the preconditions for socialism practically ripen in imperialism. These

conclusions are already included in the very definition of imperialism as mono-

poly capitalism:

This in itself determines its place in history, for monopoly that grows out

of the soil of free competition, and precisely out of free competition, is the

transition from the capitalist system to a higher socio-economic order.19

Imperialism is thus the immediate transitory stage from capitalism to socialism

which determines its place in human history:

From all that has been said in this book on the economic essence of

imperialism, it follows that we must define it as capitalism in transition,

or, more precisely, as moribund capitalism.20

The development of capitalism into imperialism was thus argued by Lenin to

be an inevitable and irreversible consequence of the economic development

of capitalism. The contradictions of capitalism are furthermore accentuated in

imperialism. According to Lenin, the relations of private property which are

preserved intact even in imperialism no longer correspond to its relations of

production: ‘Production becomes social, but appropriation remains private’.21

17 Lenin 1967d, p. 765.

18 Ibid.

19 Lenin 1967d, pp. 772–3.

20 Lenin 1967d, pp. 775–6.

21 Lenin 1967d, p. 693.

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

imperialism as the last stage of capitalism 133

Thus Lenin seemed to round off his argumentation of the consequences of

imperialism following Engels’s formulation of the basic contradiction of cap-

italism, which Kautsky had also taken as his own. But in Lenin’s analysis, this

basic contradiction took a new form and was even accentuated in imperial-

ism. Due to the monopolisation of production, ‘the social means of production

remain the private property of a few’22 (even fewer than before). And in imper-

ialism, the contradiction between private appropriation and the socialisation

of production becomes even more accentuated as the contradiction between

‘formally recognised free competition’ and factual ‘monopolistic competition’.

As a consequence, ‘the yoke of a few monopolists on the rest of the popula-

tion becomes a hundred times heavier, more burdensome and intolerable’.23

In imperialism, the basic contradiction of capitalism is developed to its utmost

form, and consequently, the relations of private property must give way to a

socialisation of the means of production which recognises that the means of

production are, in fact, already in capitalism, social means of production.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

This content downloaded from

202.142.80.242 on Sun, 28 Mar 2021 20:30:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 111 A Level Accounting P1 MCQs TopicalDocument27 pages111 A Level Accounting P1 MCQs TopicalRead and Write Publications80% (5)

- The Mother's Land - Engendering The Nation in CinemaDocument15 pagesThe Mother's Land - Engendering The Nation in CinemaKratika JoshiNo ratings yet

- Digest For Notebook FinalDocument32 pagesDigest For Notebook Finalpapam0% (1)

- The New Yorker (01.01.2024)Document72 pagesThe New Yorker (01.01.2024)nd6hzd4b6sNo ratings yet

- Suddhaseel SenDocument3 pagesSuddhaseel SenAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Ch7 Kaushik BasuDocument6 pagesCh7 Kaushik BasuAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- SCDocument7 pagesSCAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- PG Kaushik CH 7 PDFDocument6 pagesPG Kaushik CH 7 PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- SB Inward Return PDFDocument16 pagesSB Inward Return PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Partha Manifesto Prashongik PDFDocument12 pagesPartha Manifesto Prashongik PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 02 Nov 2021Document4 pagesAdobe Scan 02 Nov 2021Atri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 23 Dec 2020Document4 pagesAdobe Scan 23 Dec 2020Atri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 25 Nov 2020 PDFDocument5 pagesAdobe Scan 25 Nov 2020 PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- (B) PDFDocument7 pages(B) PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 05 Nov 2020 PDFDocument3 pagesAdobe Scan 05 Nov 2020 PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Ibsen's Political and Social IdeasDocument14 pagesIbsen's Political and Social IdeasAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Subaltern Studies As Postcolonial CriticismDocument16 pagesSubaltern Studies As Postcolonial CriticismAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- CDBC+ 20: (Foc Hasinizatien/SocDocument21 pagesCDBC+ 20: (Foc Hasinizatien/SocAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- (A) PDFDocument5 pages(A) PDFAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Representing Nation in Imagination Rabindranath TaDocument5 pagesRepresenting Nation in Imagination Rabindranath TaAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Love and Desire in Kamala Das Summer inDocument1 pageLove and Desire in Kamala Das Summer inAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Lalon's PhilosophyDocument20 pagesLalon's PhilosophyAtri Deb ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Welcome To IBPS CWEDocument1 pageWelcome To IBPS CWERamu AlladiNo ratings yet

- To, Ashutosh Kumar (Huf) Bunglow No. 92, RSC 2, SVP Nagar, Versova Andheri (West) MUMBAI 400053, Maharashtra IndiaDocument1 pageTo, Ashutosh Kumar (Huf) Bunglow No. 92, RSC 2, SVP Nagar, Versova Andheri (West) MUMBAI 400053, Maharashtra IndiaNikhil JainNo ratings yet

- CPTED GuidebookDocument68 pagesCPTED GuidebookEkaj Montealto Mayo100% (1)

- Case Application - Ch4Document2 pagesCase Application - Ch4Linh Nguyen Thi ThuyNo ratings yet

- Foreign Exchange - Basic-1Document120 pagesForeign Exchange - Basic-1Nusrat JahanNo ratings yet

- House Price Statistics For Small Areas (Hpssas)Document1,057 pagesHouse Price Statistics For Small Areas (Hpssas)mj2park28No ratings yet

- Grassroot India Mendha 2008 enDocument20 pagesGrassroot India Mendha 2008 enVivek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Yoma 73Document37 pagesYoma 73Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-13876Document2 pagesG.R. No. L-13876Bluebells33No ratings yet

- Blade Runner RPG Fiery Angels Handouts 231128Document20 pagesBlade Runner RPG Fiery Angels Handouts 231128hlib.kuchukNo ratings yet

- Canary Marketing Sues TwitterDocument5 pagesCanary Marketing Sues TwitterKhristopher J. BrooksNo ratings yet

- Psalm V MaunladDocument2 pagesPsalm V MaunladLeo Angelo MenguitoNo ratings yet

- MX-PBC-PSC: Express EasyDocument3 pagesMX-PBC-PSC: Express EasyTypes LucyNo ratings yet

- Message of Presidential Adviser On The Peace Process Teresita Quintos Deles at The Turnover and Launching of The Bangsamoro Development PlanDocument3 pagesMessage of Presidential Adviser On The Peace Process Teresita Quintos Deles at The Turnover and Launching of The Bangsamoro Development PlanOffice of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace ProcessNo ratings yet

- Criminal CourtsDocument9 pagesCriminal CourtsKelvine DemetriusNo ratings yet

- Colonials MDocument24 pagesColonials Mgebarap913No ratings yet

- Dissent of Justice LeonenDocument17 pagesDissent of Justice LeonenLhem NavalNo ratings yet

- BC337, BC337-25, BC337-40 Amplifier Transistors: NPN SiliconDocument7 pagesBC337, BC337-25, BC337-40 Amplifier Transistors: NPN SiliconoridecomNo ratings yet

- De Knecht VsDocument28 pagesDe Knecht VsDess AroNo ratings yet

- Practical Tips in Court LitigationDocument15 pagesPractical Tips in Court LitigationakosiquatogNo ratings yet

- Legal History of Medical Aid in Dying - Physician Assisted Death IDocument38 pagesLegal History of Medical Aid in Dying - Physician Assisted Death IaliceNo ratings yet

- Legal MaximsDocument42 pagesLegal MaximsRaajashekkar ReddyNo ratings yet

- Reyes Vs Capinig Position PaperDocument22 pagesReyes Vs Capinig Position PaperMartin SandersonNo ratings yet

- Sanctions As WarDocument411 pagesSanctions As WarcyberbombermanNo ratings yet

- Indonesia GHSDocument267 pagesIndonesia GHSNaveen BhargavaNo ratings yet

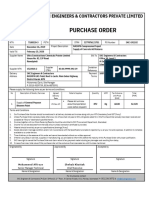

- Purchase Order: SKC Engineers & Contractors Private LimitedDocument1 pagePurchase Order: SKC Engineers & Contractors Private LimitedMohammed AffrozeNo ratings yet