Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Frontal Sinus Obliteration

Uploaded by

Princess B. MaristelaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Frontal Sinus Obliteration

Uploaded by

Princess B. MaristelaCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of Hydroxyapatite Cement for Frontal

Sinus Obliteration After Mucocele Resection

Farhan Taghizadeh, MD; Alexander Krömer, MD; Kurt Laedrach, MD, DMD

Objectives: To retrospectively evaluate our experi- trauma (26 patients [68%] in the BoneSource group and 9

ence with frontal sinus obliteration using hydroxyapa- patients [56%] in the fat obliteration group) was the most

tite cement (BoneSource; Stryker Biotech Europe, Mon- common history of mucocele formation in both groups.

treux, Switzerland) and compare it with fat obliteration Major complications in the BoneSource group included 1

over the approximate same period. Frontal sinus oblit- patient with skin fistula, which was managed conserva-

eration with hydroxyapatite cement represents a new tech- tively, and 1 patient with recurrent ethmoiditis, which was

nique for obliteration of the frontal sinus after muco- managed surgically. Both complications were not directly

cele resection. attributed to the use of BoneSource. Contour deficit of

the frontal bone occurred in 1 patient in the fat oblitera-

Methods: Exploration of the frontal sinus was per-

tion group and in none in the BoneSource group. Two

formed using bicoronal, osteoplastic flaps, with muco-

patients in the fat obliteration group had donor site com-

sal removal and duct obliteration with tissue glue and

muscle or fascia. Flaps were elevated over the perior- plications (hematoma and infection). Thirteen patients

bita, and Silastic sheeting was used to protect the Bone- in the BoneSource group had at least 1 prior attempt at

Source material from exposure as it dried. The frontal table mucocele drainage, and no statistical relation existed be-

was replaced when appropriate. tween recurrent surgery and preservation of the ante-

rior table.

Results: Sixteen patients underwent frontal sinus oblit-

eration with fat (fat obliteration group), and 38 patients Conclusion: Hydroxyapatite is a safe, effective material

underwent obliteration with BoneSource (BoneSource to obliterate frontal sinuses infected with mucoceles, with

group). Fat obliteration failed in 2 patients, who under- minimal morbidity and excellent postoperative con-

went subsequent BoneSource obliteration, and none of the tour.

patients in the BoneSource group has required removal of

material because of recurrent complications. Frontobasal Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:416-422

O

BSTRUCTION OF THE FRON- While homologous materials like ly-

tonasal duct from in- ophilized cartilage have been success-

fection, polyposis, neo- fully used to obliterate the frontal sinus,9

plasms, or traumatic in- theoretical risks of infection transmis-

jury is the most common sion have reduced their use.10 Other syn-

disease process involving the frontal si- thetic materials such as Teflon,11 polytet-

nus.1 While endoscopic procedures have rafluroethylene, and methylmetharyalte12

clear advantages in the modern manage- have all fallen out of favor for various rea-

ment of frontal sinus disease, severe trau- sons, such as high rates of infection and

matic disruptions with missing anterior extrusion, especially in the frontal si-

table bone and advanced suppuration are nus.13 These materials are also not ideal

clear indications for sinus obliteration.2 when there is missing anterior table bone,

Many options currently exist for sinus as occurs in severe trauma, often leaving

obliteration, including autologous mate- long-term frontal contouring defects.

rials such as fat,3 cartilage, muscle, can- The past decade has seen many ad-

cellous bone,4 and pericranial flaps.5 Oblit- vancements in the use of calcium phos-

eration with fat has historically been the phate biomaterials for bone replacement.

most commonly used material, with clini- One such product is calcium phosphate

cal failure rates of up to 10%6 and long- in the form of hydroxyapatite cement

term resorption rates of up to 80%, as (Ca10[PO4]6[OH]2), a paste that has been

Author Affiliations:

evaluated by magnetic resonance imag- successfully used to contour various skull

Department of

Cranio-Maxillofacial, ing.7 If any frontal bone is missing, as oc- defects including reconstruction of the fron-

Skull Base, Facial Plastic, curs in severe trauma, there is a theoreti- tofacial skeleton.14-17 This material can be

& Reconstructive Surgery, cally higher risk of mucocele reformation.8 easily contoured to fill and cover the defect

Inselspital University Hospital With all autologous materials, there ex- and dries isothermally within several min-

of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. ists a complication risk from harvesting. utes. The substance then hardens to ce-

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

416

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

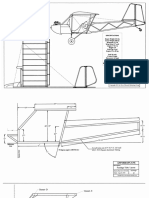

A B

C D

Figure 1. Surgical approach for obliteration. A, The frontal sinus after removal of the anterior table and excision of all mucosa (note the extension of the flap with

the release of the periorbita); B, positioning of the Silastic sheets to cover the periorbita when placing the hydroxyapatite cement (BoneSource; Stryker Biotech

Europe, Montreux, Switzerland). The frontonasal ducts at this point have been obliterated with muscle and tissue glue (not shown); C, filling the frontal sinus with

BoneSource paste and allowing it to dry for 10 to 15 minutes (note the Silastic sheets and how they help in orbital roof contouring); and D, replacement of the

anterior table over the BoneSource after the Silastic sheeting has been removed.

ment within 4 to 6 hours. It has been shown that, over presence of frontal sinus mucocele. There were 38 patients in

time, the hydroxyapatite cement becomes replaced by the BoneSource group and 16 patients in the fat obliteration

bone without volume loss.18 The material has been stable group. Each patient’s medical chart was reviewed preopera-

in its use for frontal sinus obliteration.19 In the present tively and postoperatively. Given the nature of the referral pat-

terns to our clinic, some patients referred from other coun-

study, we retrospectively review our experience with us-

tries were sent back to their countries for follow-up, with only

ing hydroxyapatite cement for frontal sinus obliteration complications or problems being reported back to our clinic.

after mucocele excision. We also report our final series

of patients who underwent frontal sinus obliteration with

fat and our use of hydroxyapatite cement for reconstruc- SURGICAL APPROACH FOR OBLITERATION

tive sinus obliteration in patients without previous mu-

cocele surgery. All patients with evidence of active mucocele infection were given

1 week of antibiotics prior to surgical intervention. A standard

coronal approach was used for all sinuses, with subperiosteal dis-

METHODS section up to the orbital rims. The supraorbital nerves were re-

leased from their canals using a Kerrison forceps, and the flaps

PATIENTS were brought to the nasal bone inferiorly, with necessary release

of the periorbita down to the orbital roof (Figure 1A). The out-

A retrospective review of all mucocele-related frontal sinus oblit- line of the frontal sinus was identified with light from an endo-

erations from 1994 to May 2005 was completed. All patients scope and then traced. A high-speed oscillating saw was then used

were treated at a single specialty clinic, with the same team of to remove the anterior table and remnants. Careful attention was

surgeons providing surgical services for the period reviewed. paid to the removal of all mucosa with forceps and high-speed

All patients had been diagnosed as having frontal sinus muco- cutting and diamond drills. The frontonasal ducts were then vi-

cele. Patients were categorized as either having undergone oblit- sualized, and pericranium or temporalis muscle and fascia were

eration with fat, starting in 1994 (fat obliteration group), or harvested for closing the duct. In most cases, fibrin glue was ap-

with hydroxyapatite cement (BoneSource; Stryker Biotech Eu- plied to this muscle to ensure proper sealing of the duct. At this

rope, Montreux, Switzerland) (BoneSource group), which first point in the fat obliteration cases, fat was harvested from the ab-

became available to our clinic in December 1997. One patient domen and used to pack the sinus. The frontal table was then re-

underwent frontal sinus obliteration with lyophilized carti- placed as best as possible. In the single case of obliteration with

lage, and 4 patients had prior sinus obliterations as part of their lyophilized cartilage, the cartilage was obtained from Neutro-

treatment for other frontal or skull base or trauma, without the medics, Cham, Switzerland.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

417

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

was then left to dry for 10 to 15 minutes (Figure 1C). The Silas-

A tic sheeting was then removed, and the BoneSource over the or-

bital roof was finely contoured. The coronal flaps were then re-

placed, and the forehead, supraorbital, and nasal contours were

checked for irregularities and asymmetries. When needed, fine

adjustments were made by adding or removing some of the dry-

ing paste. It was possible to replace the frontal sinus anterior table

bone in 16 patients in the BoneSource group (Figure 1D). The

coronal flap was then closed in the standard fashion over highly

placed, low-suction drains. These drains were sewn into place.

Postoperatively, the drains were checked to ensure nonmigra-

tion inferiorly over the BoneSource. These drains were removed

on postoperative days 1 through 3. The patients received 1 week

of postoperative antibiotics, with selective use if cultures ob-

tained from the mucocele were positive for evidence of active bac-

terial infection.

Preoperative and postoperative photographs were ob-

B

tained. When appropriate, postoperative computed tomo-

graphic scans were obtained. More of such postoperative scan-

ning was performed early in the series. Patients were then

followed up either in our center or with appropriate special-

ists in their respective countries. Statistical analysis was per-

formed to determine odds ratios and P values (2 test; P⬍.05

was considered significant) using SAS statistical software (SAS

Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show a frontal sinus mucocele,

and Figure 4 shows a frontal sinus demonstrating in-

Figure 2. A, An axial T1-weighted image of a frontal sinus mucocele tegration about 1 year after obliteration surgery.

in a 53-year-old man with extensive frontobasal trauma 11 years prior;

B, a T2-weighted coronal image of the same mucocele.

FRONTAL SINUS OBLITERATION WITH FAT

The fat obliteration group included 14 men and 2 women,

with a mean age of 47.5 years. The final fat obliteration pro-

cedure occurred in 2002. All patients in this group pre-

sented with mucoceles. Of the 16 patients, 12 (75%) were

followed up in our clinic for a mean of 22.3 months after

surgery. Nine patients (56%) had a history of frontal sinus

trauma (Table 1). The mean time from the trauma to sur-

gery for the mucocele was 10.6 years (range, 1-20 years).

Of these 9 trauma patients, only 1 patient had 2 prior at-

tempts at mucocele drainage with recurrence, while the oth-

ers were undergoing their first mucocele surgery. The other

histories included chronic sinusitis (4 patients), posttu-

mor sinonasal tumor removal (2 patients), and unknown

Figure 3. The mucocele as it extended partially out of the frontal sinus. etiology (1 patient). Of the 4 patients with chronic infec-

tion as the cause for the mucocele, 2 had drainage at-

For the BoneSource obliteration procedure, the frontal table tempts prior to the fat obliteration. The 2 patients with post-

was discarded in some cases when it was noted to be insuffi- tumor sinonasal tumor removal and the 1 patient with

cient. In some cases, this bone was atrophic with noted deficits. mucocele of unknown etiology had no prior mucocele

Once the frontal sinus mucosa was removed and the duct blocked, drainage surgical procedures.

the sinus was packed with gauze to help keep the cavity dry. Si- In regard to complications in the fat obliteration

lastic sheeting was cut and placed against the periorbita to pre- group (Table 2), the most common was short-term

vent adhesion of the BoneSource material against the eye, lead- swelling and pain (5 patients). Two patients had supra-

ing to theoretical fibrosis (Figure 1B). These sheets also allowed orbital hypoesthesia. Two patients had abdominal har-

for proper contouring of the orbital roof to provide an even sur-

face for BoneSource material to dry against. Once protected,

vesting complications (1 hematoma and 1 infection),

the nasofrontal ducts were checked to ensure proper closure. which were resolved with appropriate treatment. One

BoneSource powder was then mixed with sodium phosphate so- patient had a frontal bone contouring defect. The flap

lution. The paste was then applied to the cavity, using proper hematoma in the one patient self-resolved with conser-

amounts to obtain proper contour. When needed, the paste was vative treatment. Of the 16 patients, 2 (13%) developed

taken inferiorly to the junction of the nasal bone. The material recurrent mucoceles 4 and 6 years after fat obliteration.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

418

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

A B

Figure 4. A, Axial computed tomographic scan of the frontal sinus showing integration about 1 year after obliteration surgery; B, coronal computed tomographic

scan of the frontal sinus showing integration about 1 year after obliteration surgery.

Table 1. Histories of the Patients Prior Table 2. Complications Encountered

to the Obliteration Procedure* for Both Obliteration Procedures*

Lyophilized Complication Fat Obliteration BoneSource

History Fat Obliteration BoneSource† Cartilage

Frontal swelling or pain 5 1

Trauma 9 26 0 Frontal hypoesthesia 2 3

Infection 4 8 1 Flap hematoma 1 4

Tumor 2 3 0 Donor site hematoma 1 0

Other 1 (Unknown 1 (Orbital 0 Donor site infection 1 0

cause) decompression) Failed obliteration 2 0

Contouring deficit 1 0

*Data are given as number of patients. Recurrent mucocele 2 0

†A hydroxyapatite cement (Stryker Biotech Europe, Montreux, Switzerland). Eye edema 0 2

Skin fistula 0 1

Ethmoid abscess 0 1

These patients then underwent reexploration and oblit-

eration with BoneSource. The single patient who under- *Data are given as number of patients.

went frontal sinus obliteration with lyophilized carti-

lage also had a history of frontal sinus trauma. This

patient had no recurrences or complications as of 8 trauma group, 7 patients had 1 prior surgery attempting

years after obliteration. to externally (6 patients) or endoscopically (1 patient) drain

the mucocele. One patient had 3 prior operations to con-

FRONTAL SINUS OBLITERATION trol a cerebrospinal fluid leak in the late 1970s after severe

WITH BONESOURCE frontal and skull base trauma. Among the patients with

chronic sinus infection in the BoneSource group, 1 had un-

The BoneSource group included 27 men and 11 women, dergone a single prior attempted drainage procedure, 1 had

with a mean age of 44.7 years (range, 19-74 years). The undergone 5 prereferral drainage procedures, and 1 had

final obliteration reviewed occurred in May 2005. Long- undergone prior fat obliteration that was performed at our

term clinical follow-up or radiographic follow-up with clinic. The other patient in whom the fat obliteration had

computed tomography was completed at our clinic for failed involved a patient with tumor, who underwent a prior

18 patients, with a mean follow-up of 18 months after juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma skull base resec-

surgery. Of the 38 patients, 26 (68%) had a history of tion. Of the other 2 patients with tumor, 1 had undergone

frontal or skull base trauma, 8 (21%) had histories of a single prior procedure and the other had 8 prior at-

chronic sinus infections, 3 (8%) had undergone prior skull tempts at drainage before the BoneSource obliteration. The

base tumor surgery, and 1 had undergone prior orbital orbital decompression patient had also undergone 1 prior

decompression surgery. drainage attempt. Finally, 1 patient had undergone a pre-

Of the 26 trauma patients, we could identify the exact vious transfrontal craniotomy and external sphenoid eth-

trauma dates in 23 patients. The mean time from the date moidectomy for a brain abscess.

of trauma to the BoneSource obliteration was 13.4 years Looking at the minor complications in the BoneSource

(range, 3-40 years). Of the 38 patients, 13 (34%) had 1 prior group (Table 2), 3 patients had hematomas, which re-

procedure attempting to manage the mucocele. In the solved with conservative, nonsurgical management. A

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

419

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

tions. Hydroxyapatite cement represents one new mate-

Table 3. Histories of Patients in the Cause rial that osteointegrates into the bone and provides a stable

for BoneSource Obliteration Group and Whether contour to the frontal bone. Unlike autologous materi-

the Anterior Table Was Preserved*

als that require the frontal sinus table to remain intact,

this material is ideal when there are deficits from severe

Anterior Table Anterior Not

History Preserved Table Preserved trauma or infectious bone erosion.20 While the key to suc-

cess in this operation is clearly the effective removal of

Trauma 12 (4†) 14 (3†)

Infection 4 (1†) 4 (2†)

mucosa and obliteration of the frontonasal duct,21,22 the

Tumor 0 3 (2‡) ability to properly close the anterior table is difficult in

Other 0 1 (1†) many revision cases after trauma repair, skull base tu-

mor surgery, or failed recurrent infectious drainage. In

*Data are given as number of patients. BoneSource is a hydroxyapatite this case series, we reviewed our 11 years of experience

cement (Stryker Biotech Europe, Montreux, Switzerland). with frontal sinus obliteration for mucoceles using fat,

†Indicates the number of patients in the listed category who had at least

1 previous surgery attempting to manage the mucocele. cartilage, and, since 1997, BoneSource.

Our clinic is a large tertiary care trauma and skull base

referral center, with patients coming both from our ser-

vice area and from other countries in Europe and the Middle

fourth patient with subgaleal hematoma was taken to the

East. The large volume of treated skull base trauma

operating room for drainage, and this patient had no fur-

contributed to this patient group being the largest pri-

ther flap issues. Three patients had hypesthesia of cra-

mary source of our patients with mucoceles. While we fol-

nial nerve V1, with 1 case resolving 3 months after sur-

lowed 12 patients (75%) in the fat obliteration group and

gery. One patient had eyelid edema and another had

18 patients (47%) in the BoneSource group for a long term

postoperative diplopia from edema, both of which quickly

in our clinic, the nature of the referral system from other

self-resolved. One patient had frontal pain, which was

countries is such that patients are followed up in their re-

short lived. Looking at the larger complications, the pa-

spective countries and we receive reports of any compli-

tient with a history of multiple surgical procedures for

cations. We are confident using this system of follow-up,

cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea required 2 further explo-

given the pathophysiologic features of frontal sinus mu-

rations for ethmoidal roof abscesses 4 months and 2 years

cocele disease, which can take many years to manifest. In

postoperatively. These infections did not extend into the

this series, the mean time from frontal trauma occur-

obliterated frontal sinus. A patient who had undergone

rence to the obliteration procedure was 10.6 years in the

a previous craniotomy for a brain abscess developed small

fat obliteration group and 13.4 years in the BoneSource

fistulas of the nasal root 1 year after surgery and a su-

group. Following up multinational patients over such a

praorbital fistula 2 years after surgery. These healed with

long period is nearly impossible. To date, our longest pe-

conservative antibiotic treatments and wound care with

riod of follow-up for a patient in the BoneSource group is

no recurrence to date (3 years).

8 years, and we feel comfortable with our system of fol-

Of the 38 patients in the BoneSource group, 16 (42%)

low-up for patients who can make regular visits to our cen-

had their anterior tables preserved and placed over the

ter and patients for whom other physicians send us re-

BoneSource (Table 3). The other 22 patients had their

ports of any complications.

anterior tables assessed as being unusable and were thus

The surgical techniques we used for treating frontal

discarded. Of the13 patients who had undergone 1 prior

sinus mucocele are similar to those published previ-

mucocele procedure, 5 (38%) had their anterior tables

ously for fat obliteration by Weber et al7 and for hydroxy-

preserved. Of the other 25 patients, 11 had their ante- apatite cement by Petruzzelli and Stankiewicz.10 For the

rior tables replaced. The breakdown of the history of these fat obliteration procedure, the only difference in our tech-

patients is given in Table 3. A 2 analysis between the nique is the use of temporalis muscle and fascia with fi-

histories and the preservation of the anterior table pro-

brin glue to seal the duct. For the BoneSource oblitera-

vided a P value of .39 (nonsignificant). An odds ratio

tion procedure, there are a few modifications in our

analysis on the null hypothesis of there being a link be-

technique worth mentioning. In patients with identifi-

tween previous mucocele surgery and discarding the an-

able supraorbital nerves, these nerves are released from

terior table was rejected (odds ratio, 0.80; 95% confi-

their foramina and the flap is elevated over the orbits such

dence interval, 0.16-3.77). Similar analysis on just the

that the orbital roof is visible. In this area (Figure 1A),

trauma patients gave similar rejection (odds ratio, 0.83;

Silastic sheets are cut and temporarily placed against the

95% confidence interval, 0.10-6.04). All patients in the

periorbita to protect it from coming into contact with the

BoneSource group were noted to have good frontal con-

BoneSource as it dries. This is done to prevent the theo-

tour during their initial postoperative evaluation. Of the

retical problem of having the hydroxyapatite cement dry

18 patients with long-term follow-up, all had good fron-

against the periorbita and cause unwanted adhesion. These

tal contours whether they had the anterior table pre-

sheets also provide a nice surface to properly contour the

served or not.

BoneSource as it comes to the orbital roof.

In the fat obliteration group, 2 patients developed re-

COMMENT current mucoceles at 4 and 6 years after surgery, giving

us a recurrent infection rate of 13% in this small group.

There has been much discussion about the ideal mate- The patient who had recurrence 6 years later had 5 prior

rial for frontal sinus obliteration for mucocele infec- drainage procedures at outside facilities to manage his

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

420

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

chronic frontal sinusitis. This patient is currently in his unlikely, given the intraoperative waiting for BoneSource

fifth year after the BoneSource obliteration without evi- solidification, that suction drains would affect this sub-

dence of recurrence. The other recurrence was in a pa- stance postoperatively. Because of our superior orbital re-

tient with extensive skull base tumor surgery for a large lease for the placement of the protective Silastic sheets, 2

juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Our recurrence patients had orbital edema, which resolved without se-

rate is higher than the 3% reported in the largest series quelae. In the 2 patients with the larger complications of

by Hardy and Montgomery,3 though our numbers in this the fistula and the need for revision ethmoidectomy, we

series from 1994 to the present are relatively small. These do not believe that the BoneSource contributed to either

failures in patients with multiple prior surgical proce- of these complications. The patient with the nasofrontal

dures or extensive transfrontal tumor surgery brings to and supraorbital soft tissue fistula had a prior brain ab-

light previous observations that despite duct oblitera- scess, underlying bone necrosis, and soft tissue chronic

tion, poor fat vascularization may contribute to recur- inflammation over these areas prior to the surgery, and both

rent mucoceles in select cases.8 To date, these 2 patients fistulas resolved with wound care and antibiotic therapy.

in whom fat obliteration had failed have not had recur- The patient with the ethmoid abscess necessitating 2 drain-

rence for 5 years and 1 year since the BoneSource oblit- age procedures had 3 prior skull base procedures for ce-

eration. It will be interesting to see how such patients rebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea after his initial frontal sinus

with multiple or extensive surgical procedures fare in the and skull base surgery. Neither ethmoidal drainage pro-

long term with BoneSource. cedure involved the frontal sinus or subcutaneous tis-

The single patient who underwent the lyophilized car- sues, and the BoneSource obliteration did not seem to be

tilage obliteration also had no further complications or affected by this infection. This patient also has not had any

recurrences of the mucocele to date. Our experience with more complications after these ethmoid procedures.

this substance for frontal sinus obliteration is too lim- In this case series, special focus was given to patients

ited to make further noteworthy comments. However, with diagnosed frontal sinus mucoceles, with several pa-

we agree that the theoretical risk of disease transmis- tients in whom fat obliteration had failed or who had pre-

sion, the lack of cost savings, and the availability of other vious procedures for attempted drainage. Friedman et al17

substances like hydroxyapatite cement makes this a less originally questioned whether the existence of frontal si-

attractive option. The single lyophilized cartilage oblit- nus mucoperiosteal disease increased the complication

eration in this series was completed in 1997, the same rate of hydroxyapatite cement implantation. In a recent

year hydroxyapatite cement became available to our clinic. analysis by Mathur et al,24 mucoperiosteal disease did not

The other complications in the fat obliteration group appear to predict complication outcome using carbon-

were generally minor, though the presence of donor site ated apatite and hydroxyapatite. The combined infec-

issues is noteworthy. The swelling, pain, and hematoma tion risk in this article was 13%. The authors also cau-

complications were managed conservatively without se- tioned against the use of these substances in obliterating

quelae. While care is taken to preserve the supraorbital sinuses exposed to sinus or oral secretions.24 Our expe-

nerves, hypoesthesia is unavoidable in patients with re- rience with BoneSource is contrary to these reports, with

vision surgery raising multiple coronal flaps. Given the only 2 patients having recurrent infections after the pro-

large number of trauma patients in this study who had cedure, both of whom were conservatively treated with-

all had previous coronal flaps, the incidence is relatively out implant removal. Several technique variations may

low in both this group and the BoneSource group. The have contributed to this low infection rate in a group con-

final complication worth noting was the frontal bone defi- sidered to be at higher risk by previous authors. The first

cit noted in 1 patient. One factor that spurred the use of factor may be the use of the protective Silastic sheets to

BoneSource in these patients in 1997 was the issue of poor prevent contact of the hydroxyapatite cement with the

frontal bone contour in patients with previous trauma. orbits. We have found that these sheets also prevent the

The use of hydroxyapatite cement in craniofacial recon- hydroxyapatite cement paste from going into the eth-

struction has been noted to be safe and effective.23 Our moid sinus region, which was open in many of the pa-

experience with using hydroxyapatite cement for such tients from previous procedures. Unfortunately, the pres-

reconstructions has been very successful. In the medi- ence of open ethmoid cells was not specifically noted in

cal chart reviews, we found 4 cases of extensive frontal operative reports, which focused on the frontal sinus oblit-

bone defects from tumors and a hemangioma that were eration. Possibly, placing fascia or pericranium over the

successfully reconstructed with good cosmetic and func- open ethmoid roof might be beneficial to block this hy-

tional results. In the BoneSource group, all of the pa- pothesized source of infection. Overall, we believe that

tients had good contour in the short-term postoperative keeping the hydroxyapatite cement off the nasal mu-

evaluation, with similar results noted in those patients cosa until it dries is an important procedural step. The

we have seen postoperatively. second favorable factor might be the meticulous oblit-

The complications in the BoneSource obliteration group eration of the frontonasal duct. While this step is key to

included 3 patients who developed small-flap hemato- any obliteration surgery, the use of tissue glue with the

mas, which resolved without a need for further drainage, muscle or fascia and then waiting for the glue to dry be-

and 1 patient who was taken back for drainage. All pa- fore placing the BoneSource might be key to ensuring

tients with coronal flaps had coronal drains placed, and proper duct closure. The third factor may be the impor-

care was taken to position these posteriorly so that they tance of not replacing the anterior table bone when it is

do not ride up to where the BoneSource is present. In our deemed to be of poor stock. While our data showed no

experience, however, we have come to believe that it is statistically significant indicator of which patients had

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

421

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

their bones preserved, we think it is advantageous to re- Accepted for Publication: August 29, 2006.

move infected, poorly vascularized, or cosmetically de- Correspondence: Farhan Taghizadeh, MD, Inselspital

ficient bone and only have BoneSource in the cavity. The University Hospital of Bern, CH–3010 Bern, Switzer-

final factor was our reluctance to operate on any muco- land (ftaghizadeh@comcast.net).

cele with active infection, preferring 1 week of antibi- Financial Disclosure: None reported.

otic therapy prior to surgery. Acknowledgment: We give special thanks to the Depart-

While long-term follow-up is still needed, none of the ment of Biostatistics of the University of Bern for review-

patients in the BoneSource obliteration group has had re- ing these data.

current mucoceles to date. Despite this success, the issue

of cost in using this substance cannot be ignored. Fattahi REFERENCES

et al25 have recently published an article questioning the

cost-effectiveness of hydroxyapatite cement in frontal 1. Duvoisin B, Schnyder B. Do abnormalities of the frontonasal duct cause frontal

sinus obliteration compared with fat. Outside of the con- sinusitis? a CT study of 198 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:1295-

touring issues in select patients in whom BoneSource oblit- 1298.

2. Klotch DW. Frontal sinus fractures: anterior skull base. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;

eration is needed because of anterior table loss, an argu- 16:127-134.

ment can certainly be made that this substance should be 3. Hardy JM, Montgomery WW. Osteoplastic frontal sinusotomy: an analysis of 250

used selectively. In this series, neither the presence of pre- operations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85:523-532.

vious mucocele surgery nor the presence of trauma cor- 4. Shumrick KA, Smith CP. The use of cancellous bone for frontal sinus oblitera-

related with preservation of the anterior table. This bone tion and reconstruction of frontal bony defects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

1994;120:1003-1009.

was replaced when it was believed to be more advanta- 5. Ducic Y, Stone TL. Frontal sinus obliteration using a laterally based pedicled peri-

geous to do so. In the group as a whole, 16 patients were cranial flap. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:541-545.

assessed as having good enough anterior table frontal 6. Catalano PJ, Lawson W, Som P, Biller HF. Radiographic evaluation and diagno-

bone to warrant an attempt to provide cover for the sis of the failed frontal osteoplastic flap with fat obliteration. Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg. 1991;104:225-234.

BoneSource. In the rest of the patients, it was believed that 7. Weber R, Draf W, Keerl R, et al. Osteoplastic frontal sinus surgery with fat oblit-

the frontal sinus contour would be better without the bone eration: technique and long-term results using magnetic resonance imaging in

being replaced. If cost is a limiting factor, could the con- 82 operations. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1037-1044.

dition of the anterior table be the key element in decid- 8. Donald PJ, Ettin M. The safety of frontal sinus fat obliteration when sinus walls

ing whether to obliterate with fat or hydroxyapatite? There are missing. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:190-193.

9. Kalavrezos ND, Gratz KW, Warnke T, Sailer HF. Frontal sinus fractures: com-

certainly is literature to suggest that the risk of fat oblit- puted tomography evaluation of sinus obliteration with lyophilized cartilage.

eration is higher if the frontal sinus bone is missing.8 Given J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1999;27:20-24.

that only long-term mucocele recurrence data exist for 10. Petruzzelli GJ, Stankiewicz JA. Frontal sinus obliteration with hydroxyapatite cement.

fat obliteration and given the lengthy nature of this dis- Laryngoscope. 2002;112:32-36.

11. Barton RT. The use of synthetic implant material in osteoplastic frontal sinusotomy.

ease process and its recurrence, the answer to the ques- Laryngoscope. 1980;90:47-52.

tion of when to use fat vs BoneSource will come when 12. Blum KS, Schneider SJ, Rosenthal AD. Methyl methacrylate cranioplasty in chil-

patients like those in our series are followed up for a longer dren: long-term results. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997;26:33-35.

period. To date, our longest period of follow-up for a 13. Benzel EC, Thammavaram K, Kesterson L. The diagnosis of infections associ-

patient in the BoneSource obliteration group is 8 years ated with acrylic cranioplasties. Neuroradiology. 1990;32:151-153.

14. Kamerer DB, Hirsch BE, Snyderman CH, et al. Hydroxyapatite cement: a new method

without apparent complications, and both of our pa- for achieving watertight closure in transtemporal surgery. Am J Otol. 1994;

tients in whom fat obliteration had failed are doing well 15:47-49.

with the BoneSource. 15. Kveton JF, Freidman CD, Costantino PD. Indications for hydroxyapatite cement

reconstruction in lateral skull base surgery. Am J Otol. 1995;16:465-469.

16. Kveton JF, Freidman CD, Piepmeier JM, et al. Reconstruction of suboccipital cra-

CONCLUSIONS niotomy defects with hydroxyapatite cement: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope.

1995;105:156-159.

17. Friedman CD, Costantino PD, Synderman CH, Chow LC, Takagi S. Reconstruc-

tion of the frontal sinus and frontofacial skeleton with hydroxyapatite cement.

This study demonstrates that hydroxyapatite cement is

Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2:124-129.

a viable option for frontal sinus obliteration after muco- 18. Friedman CD, Constantino PD, Jones K, Chow LC, Pelzer HJ, Sisson GA. Hy-

cele resection. Fat obliteration is the traditional alterna- droxyapatite cement, II: obliteration and reconstruction of the cat frontal sinus.

tive for frontal sinus obliteration for mucoceles, al- Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:385-389.

though the 2 patients in whom this procedure failed were 19. Snyderman CH, Scioscia K, Carrau RL, Weissman JL. Current hydroxyapatite:

an alternative method of frontal sinus obliteration. Otolaryngol Clin North Am.

successfully treated with BoneSource obliteration. The 2001;34:179-191.

majority of patients in this study developed mucoceles 20. Bent JP III, Spears RA, Kuhn FA, Stewart SM. Combined endoscopic intranasal

after either previous trauma or tumor surgery, with a and external frontal sinusotomy. Am J Rhinol. 1997;11:349-354.

handful having had multiple prior surgical procedures 21. Rohrich RJ, Mickel TJ. Frontal sinus obliteration: in search of the ideal autog-

enous material. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:580-585.

or prior attempts at mucocele excision. In this complex

22. Calcaterra TC, Strahan RW. Osteoplastic flap technique for disease of the frontal

group, hydroxyapatite cement represented a good op- sinus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;132:505-510.

tion for obliteration, with no patients necessitating im- 23. Lykins CL, Friedman CD, Costantino PD, Horioglu R. Hydroxyapatite cement in

plant removal to date. This substance also allows for the craniofacial skeletal reconstruction and its effects on the developing craniofa-

option of not replacing the anterior table when deemed cial skeleton. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:153-159.

24. Mathur KK, Tatum SA, Kellman RM. Carbonated apatite and hydroxyapatite ce-

insufficient. The postoperative cosmetic contours of the ment in craniofacial reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:379-383.

frontal region were noted to be very good in all our pa- 25. Fattahi T, Johnson C, Steinberg B. Comparison of 2 preferred methods used for

tients. frontal sinus obliteration. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:487-491.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 8, NOV/DEC 2006 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

422

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archfaci.jamanetwork.com/ by a McMaster University User on 03/25/2016

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Percent by VolumeDocument19 pagesPercent by VolumeSabrina LavegaNo ratings yet

- 4 Force & ExtensionDocument13 pages4 Force & ExtensionSelwah Hj AkipNo ratings yet

- 18 Ray Optics Revision Notes QuizrrDocument108 pages18 Ray Optics Revision Notes Quizrraafaf.sdfddfaNo ratings yet

- Digging Deeper: Can Hot Air Provide Sustainable Source of Electricity?Document2 pagesDigging Deeper: Can Hot Air Provide Sustainable Source of Electricity?Рустам ХаджаевNo ratings yet

- C.Abdul Hakeem College of Engineering and Technology, Melvisharam Department of Aeronautical Engineering Academic Year 2020-2021 (ODD)Document1 pageC.Abdul Hakeem College of Engineering and Technology, Melvisharam Department of Aeronautical Engineering Academic Year 2020-2021 (ODD)shabeerNo ratings yet

- The Passion For Cacti and Other Succulents: June 2017Document140 pagesThe Passion For Cacti and Other Succulents: June 2017golf2010No ratings yet

- 08 Activity 1 (10) (LM)Document2 pages08 Activity 1 (10) (LM)Jhanine Mae Oriola FortintoNo ratings yet

- AssessmentDocument9 pagesAssessmentJuan Miguel Sapad AlpañoNo ratings yet

- EPCC Hydrocarbon Downstream L&T 09.01.2014Document49 pagesEPCC Hydrocarbon Downstream L&T 09.01.2014shyaminannnaNo ratings yet

- Bảng giá FLUKEDocument18 pagesBảng giá FLUKEVăn Long NguyênNo ratings yet

- Arbor APS STT Unit 01 Design Basics 25 Jan2018Document31 pagesArbor APS STT Unit 01 Design Basics 25 Jan2018masterlinh2008No ratings yet

- Unit 3Document12 pagesUnit 3Erik PurnandoNo ratings yet

- From Input To Affordance: Social-Interactive Learning From An Ecological Perspective Leo Van Lier Monterey Institute Oflntemational StudiesDocument15 pagesFrom Input To Affordance: Social-Interactive Learning From An Ecological Perspective Leo Van Lier Monterey Institute Oflntemational StudiesKayra MoslemNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Math Problem of The Day December ActivityDocument5 pagesKindergarten Math Problem of The Day December ActivityiammikemillsNo ratings yet

- Presentation On 4G TechnologyDocument23 pagesPresentation On 4G TechnologyFresh EpicNo ratings yet

- Shree New Price List 2016-17Document13 pagesShree New Price List 2016-17ontimeNo ratings yet

- Plans PDFDocument49 pagesPlans PDFEstevam Gomes de Azevedo85% (34)

- HCPL 316J 000eDocument34 pagesHCPL 316J 000eElyes MbarekNo ratings yet

- Gamak MotorDocument34 pagesGamak MotorCengiz Sezer100% (1)

- Study The Effect of Postharvest Heat Treatment On Infestation Rate of Fruit Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Cultivars Grown in AlgeriaDocument4 pagesStudy The Effect of Postharvest Heat Treatment On Infestation Rate of Fruit Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Cultivars Grown in AlgeriaJournal of Nutritional Science and Healthy DietNo ratings yet

- Nivel VV-VW Board User Guide enDocument5 pagesNivel VV-VW Board User Guide enHarveyWishtartNo ratings yet

- Sales 20: Years Advertising Expense (Millions) X Sales (Thousands) yDocument8 pagesSales 20: Years Advertising Expense (Millions) X Sales (Thousands) ybangNo ratings yet

- 3rd Quarter Exam (Statistics)Document4 pages3rd Quarter Exam (Statistics)JERALD MONJUANNo ratings yet

- 2015 Nos-Dcp National Oil Spill Disaster Contingency PlanDocument62 pages2015 Nos-Dcp National Oil Spill Disaster Contingency PlanVaishnavi Jayakumar100% (1)

- AKI in ChildrenDocument43 pagesAKI in ChildrenYonas AwgichewNo ratings yet

- 12.5 Collision Theory - ChemistryDocument15 pages12.5 Collision Theory - ChemistryAri CleciusNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Active Faults and Other Earthquake Sources: Learning OutcomeDocument3 pagesModule 4 Active Faults and Other Earthquake Sources: Learning OutcomeFatima Ybanez Mahilum-LimbagaNo ratings yet

- Twilight PrincessDocument49 pagesTwilight PrincessHikari DiegoNo ratings yet

- Inverse of One-To-One FunctionDocument4 pagesInverse of One-To-One FunctionKathFaye EdaNo ratings yet

- Cross Talk Details and RoutingDocument29 pagesCross Talk Details and RoutingRohith RajNo ratings yet