Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bartels AJGP2014

Uploaded by

Jiachun LiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bartels AJGP2014

Uploaded by

Jiachun LiCopyright:

Available Formats

Long-Term Outcomes of a Randomized Trial

of Integrated Skills Training and Preventive

Healthcare for Older Adults with Serious

Mental Illness

Stephen J. Bartels, M.D., M.S., Sarah I. Pratt, Ph.D., Kim T. Mueser, Ph.D.,

Brent P. Forester, M.D., Rosemarie Wolfe, M.S., Corinne Cather, Ph.D., Haiyi Xie, Ph.D.,

Gregory J. McHugo, Ph.D., Bruce Bird, Ph.D., Kelly A. Aschbrenner, Ph.D.,

John A. Naslund, M.P.H., James Feldman, M.D.

Objective: This report describes 1-, 2-, and 3-year outcomes of a combined psychosocial

skills training and preventive healthcare intervention (Helping Older People Experience

Success [HOPES]) for older persons with serious mental illness. Methods: A randomized

controlled trial compared HOPES with treatment as usual (TAU) for 183 older adults

(age ! 50 years [mean age: 60.2]) with serious mental illness (28% schizophrenia, 28%

schizoaffective disorder, 20% bipolar disorder, 24% major depression) from two

community mental health centers in Boston, Massachusetts, and one in Nashua, New

Hampshire. HOPES comprised 12 months of weekly skills training classes, twice-

monthly community practice trips, and monthly nurse preventive healthcare visits,

followed by a 1-year maintenance phase of monthly sessions. Blinded evaluations of

functioning, symptoms, and service use were conducted at baseline and at a 1-year (end

of the intensive phase), 2-year (end of the maintenance phase), and 3-year (12 months

after the intervention) follow-up. Results: HOPES compared with TAU was associated

with improved community living skills and functioning, greater self-efficacy, lower

overall psychiatric and negative symptoms, greater acquisition of preventive healthcare

(more frequent eye exams, visual acuity, hearing tests, mammograms, and Pap smears),

and nearly twice the rate of completed advance directives. No differences were found for

medical severity, number of medical conditions, subjective health status, or acute service

use at the 3-year follow-up. Conclusion: Skills training and nurse facilitated preventive

healthcare for older adults with serious mental illness was associated with sustained

long-term improvement in functioning, symptoms, self-efficacy, preventive healthcare

screening, and advance care planning. (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 22:1251e1261)

Received September 25, 2012; revised March 28, 2013; accepted April 24, 2013. From the Department of Psychiatry (SJB, SIP, KTM, KAA) and

Department of Community and Family Medicine (SJB), Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH; The Dartmouth Institute for

Health Policy and Clinical Practice (SJB, SIP, JAN), Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH; Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center (KTM, RW,

HX, GJM), Lebanon, NH; Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation (KTM), Boston University, Boston, MA; Department of Psychiatry (BPF),

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA; Geriatric Psychiatry Research Program (BPF), McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA; Schizophrenia Program

(CC), Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Vinfen (BB), Cambridge, MA; and Massachusetts Mental Health Center (JF), Boston, MA.

Send correspondence and reprint requests to Stephen J. Bartels, M.D., M.S., Centers for Health and Aging, 46 Centerra Parkway, Ste. 200,

Lebanon, NH 03766. e-mail: sbartels@dartmouth.edu

! 2014 American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.04.013

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014 1251

Long-Term Outcomes of the HOPES Intervention

Key Words: Older adults, serious mental illness, psychosocial skills training, healthcare

management, preventive healthcare, integrated care

in the community with nurse coordination of preven-

INTRODUCTION tive healthcare as an integrated component. In a series

of studies, we reported that HOPES is associated with

The aging of the baby boomer population will

improved psychosocial outcomes after 1 year of

dramatically impact the number of middle aged and

weekly skills training and a second year of monthly

older adults with serious mental illness (SMI) over

maintenance sessions18 and with improved executive

the coming decades, foreshadowing an unprece-

functioning at 1, 2, and 3 years of follow-up.19

dented challenge to a public mental health system

The purpose of this final report of primary study

unprepared to address the special needs of this

outcomes is to address the following two remaining

emerging demographic. Adults with SMI constituted

study questions: (1) Does HOPES result in long-term

over 4% of those age 55 and older or 3.4 million

improved psychosocial functioning that persists at

adults in 20101,2 and are projected to nearly double

the 3-year follow-up after withdrawing maintenance

by 2050.3 In contrast to an array of evidence-based

sessions and nurse health management? (2) Is HOPES

interventions and implementation guides targeting

associated with improved preventive healthcare and

younger adults,4,5 few models of care are specifically

reduced acute service use?

designed for older adults with SMI. Among available

To address these questions, we evaluated 3-year

interventions, those that have emerged as effective

psychosocial, preventive healthcare, and service use

include combined cognitive behavioral therapy and

outcomes of a randomized controlled trial comparing

social skills training (CBSST),6e8 group-based

HOPES with treatment as usual (TAU) at a 1-year

psychosocial support,9 and functional adaptation

(end of the intensive phase of skills training), 2-year

skills training (FAST).10,11 Interventions such as these

(end of the maintenance phase), and 3-year (12

are necessary to address the complex psychosocial

months after intervention withdrawal) follow-up. We

and healthcare needs of this rapidly growing

hypothesized that HOPES compared with TAU at the

subgroup with the highest per person Medicare and

3-year follow-up is associated with greater long-term

Medicaid costs,12 rates of institutionalization over

improvement in independent living skills, social

three times those of other Medicaid beneficiaries,13

skills, self-efficacy, and psychiatric symptom severity

and greater use of emergency care than older adults

and with a greater quality of preventive healthcare

without SMI.14

and lower acute service use.

Several factors—lack of independent living skills,

poor social skills, and medical comorbidity—are

strongly associated with high-cost service use and

differentiate older adults with SMI living in nursing METHODS

homes from those in the community.12 In addition,

A randomized controlled trial compared

persons with SMI, when compared with those

outcomes for HOPES and TAU at 1, 2, and 3 years.

without, are known to be at risk for receiving

Written informed consent was obtained through

preventive healthcare services at a lower rate.15 To

procedures approved by the Committee for the

address these needs, we developed and pilot-tested

Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College

an intervention combining community living and

and by the institutional review boards specific to

social skills training with integrated preventive

each site.

healthcare.16,17 The HOPES (Helping Older People

Experience Success) program is designed to improve

Study Participants

independent functioning and community tenure by

teaching social skills, community living skills, and Community-dwelling adults with SMI age 50 or

healthy living skills to older persons with SMI living older (N ¼ 183) were recruited from two community

1252 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014

Bartels et al.

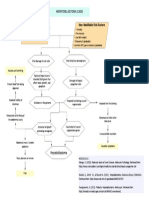

FIGURE 1. Consort diagram.

mental health agencies in Boston, Massachusetts, and conjunction with documented persistent impairment

one in Nashua, New Hampshire, and were random- in multiple areas of functioning. Exclusion criteria

ized to HOPES (N ¼ 90) or TAU (N ¼ 93). Eligibility were residence in a nursing home or other institu-

criteria included ability and willingness to provide tional setting, primary diagnosis of dementia or

informed consent and an Axis I disorder diagnosis of significant cognitive impairment as indicated by

schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar a Mini Mental Status Exam score less than 20,21

disorder, or major depression based on the Struc- physical illness expected to cause death within

tured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical 1 year, or current substance dependence. Figure 1

Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition20 in summarizes the flow of participants in the study.

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014 1253

Long-Term Outcomes of the HOPES Intervention

Interventions or outreach by non-nurse clinicians; individual

therapy; and access to rehabilitation services, such as

HOPES. HOPES targets psychosocial functioning

groups and psychoeducation.

and preventive healthcare.17 The psychosocial

component consists of weekly skills training classes

Measures

delivered over 1 year, followed by a 1-year mainte-

nance phase with monthly booster sessions. The Community living skills were assessed from three

HOPES social rehabilitation curriculum, based on perspectives: participant self-report, case manager

social skills training,22 is manualized and organized ratings of observed functioning in the community, and

into seven modules: Communicating Effectively, performance-based assessments of simulated tasks. The

Making and Keeping Friends, Making the Most of Independent Living Skills Survey23 is a participant

Leisure Time, Healthy Living, Using Medications self-report measure of functioning assessing 10 areas of

Effectively, Living Independently in the Community, community living activities. The Multnomah Commu-

and Making the Most of a Health Care Visit. A nity Ability Scale24 is a 17-item measure of observed

complete list of topics covered is found in our report of community functioning completed by interviewing

interim outcomes.17 Sessions were video recorded and each individual’s case manager. The University of

evaluated for fidelity by two authors (SIP and KTM). California San Diego (UCSD) Performance-based Skills

HOPES training sessions consisted of 8e10 partici- Assessment evaluates basic living skills using simulated

pants and were delivered in mental health centers and tasks and role play in five areas: communication, trip

senior centers in the community. To minimize trans- planning, transportation, finances, and shopping.25 The

portation challenges, participants attended two Social Behavior Schedule26 is a 23-item measure of

sessions on the same day consisting of a 90-minute social functioning in individuals with SMI. The Revised

morning session focused on a specific skill and a 60- Self-Efficacy Scale consists of 57 statements rating

minute afternoon session to consolidate the selected perceived self-efficacy in social functioning and in

skill using role-play exercises, with a lunch break in managing symptoms.27

between to encourage socialization. In addition, The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale28 and the Scale for

twice-monthly community trips were organized so the Assessment of Negative Symptoms29 were used to

participants could practice skills related to the current assess psychiatric symptom severity and negative

module topics in the community (e.g., bus station to symptoms over the prior 2 weeks. Depressive

practice using public transportation), and participants symptom severity was assessed with the Center for

were encouraged to practice new skills with a family Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.30 Health

member or friend. Attendance across sites was status was assessed with the 36-item Short Form

approximately 75% in year 1 and 70% in year 2. Health Survey (SF-36)31 and an interview-based

The preventive healthcare component consists of version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index.32 Self-

monthly meetings with a nurse embedded in the report and medical record reviews were used to

mental health setting who evaluates participants’ determine acute service use (e.g., hospitalizations,

healthcare needs focusing on facilitating preventive emergency room visits) and to quantify the proportion

screening, advance care planning, and coordination of preventive healthcare indicators from recommended

of primary healthcare visits. Goals were collabora- screening examinations by the U.S. Preventive Services

tively set by the nurse and each participant based on Task Force.33 A detailed description of procedures and

a list of recommended preventive health screenings.17 measures are provided in a previous report.18

Skills training leaders and nurses met weekly to

coordinate the psychosocial and preventive health-

Study Procedures

care components. Participants attended an average of

66% of the nurse visits across sites. After obtaining informed consent, participants

TAU. Participants in both groups continued to completed baseline assessments and were random-

receive the same services they had been receiving ized to HOPES or TAU. Assessors were blind to

before the study. Routine mental health services at all treatment group, and participants were reminded not

sites included pharmacotherapy, case management, to reveal information about their treatment to the

1254 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014

Bartels et al.

interviewer. Randomization was conducted at the and the correlation between baseline and 3-year

individual level and stratified by diagnosis (schizo- outcomes. The following thresholds, defined by

phrenia spectrum or mood disorder) and gender. A Cohen,37 were used to determine whether an effect

block randomization approach was used to ensure size was small (0.20), moderate (0.50) or large (0.80).

that no more than four participants could be Positive effect sizes denote increases in HOPES rela-

randomized to the same treatment group in a row. tive to TAU, and negative effect sizes denote

Participants were paid for completing assessments decreases in HOPES relative to TAU.38

but not for participating in HOPES. Chi-square analyses and number needed to treat

(NNT)39 were used to evaluate the categorical

outcomes of receipt of preventive healthcare. As

Statistical Analyses

determined in a prior study,40 NNT for one person to

Sample size was determined by computing statis- obtain preventive health screening, cancer screening,

tical power to detect effect sizes based on our pilot or completion of advance directives was calculated as

study of the HOPES program.16 Two tailed t tests and the inverse of the absolute risk reduction for not

c2 analyses were used to compare HOPES and TAU receiving either of these types of preventive healthcare.

on demographic characteristics, psychiatric history,

and outcome measures at baseline. Treatment effects

were evaluated by conducting intent-to-treat anal-

yses on the full sample of randomized study partic- RESULTS

ipants, regardless of their exposure to treatment.

HOPES Versus TAU at Baseline and 3-Year

A mixed-effects linear model was used for analysis,

Follow-Up

which does not drop subjects with missing data

because the statistical inference model assumes data Participants assigned to HOPES did not differ

missing at random. A doubly multivariate repeated significantly from those assigned to TAU on any

measures analysis of variance, simultaneously demographic, diagnostic, or baseline measures, with

analyzing all three dependent measures of commu- the exception of a greater rate of asthma in HOPES

nity functioning, guarded against potential inflation compared with TAU group (N ¼ 18 versus N ¼ 7;

of alpha with multiple dependent variables. There- p ¼ 0.017) (Table 1). We compared baseline demo-

after, an analysis of covariance approach controlling graphics, functioning, and symptoms of participants

for gender and diagnosis was used to test for treat- who completed the 3-year assessment (N ¼ 129) with

ment effects on each of the dependent variables those lost at the 3-year follow-up (N ¼ 54). Partici-

separately. Because there were no significant differ- pants lost to follow-up were slightly older (mean age:

ences between HOPES and TAU at baseline, rather 62.7 $ 9.3 versus 59.1 $ 7.1; t test ¼ 2.58; df ¼ 181;

than fitting parametric curves with random effects, p ¼ 0.01) and had greater self-efficacy (mean Revised

we included the baseline as a covariate and fit base- Self Efficacy Scale score: 72.5 $ 17.9 versus 65.6 $

line adjusted mean response profile models,34 also 19.0; t test ¼ %2.36; df ¼ 181; p ¼ 0.02).

referred to as covariance pattern models,35 selecting Fewer than 2% of observations were missing at

appropriate covariance structures as well as missing baseline for the Center for Epidemiologic Studies

data with maximum likelihood estimation.36 Depression Scale, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and

Site was included in initial analyses but was Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. At the 3-year follow-

dropped from the final models because it did not up, an average of 34% of observations were missing

alter the main effects. Because the baseline was (range: 31%e39%), except for the Multnomah Scale,

statistically adjusted, treatment effects were evalu- which had 50% missing observations. This rate of

ated with group main effects (i.e., differences in missing observations was expected because 30%

group mean response profiles). Two-tailed statistical (N ¼ 54) of participants were lost at the 3-year

tests were conducted, and differences were consid- follow-up and the Multnomah Scale requires

ered statistically significant based on p #0.05. Effect locating and interviewing clinical providers who

sizes were computed using Cohen’s d and an anal- have detailed knowledge of participants’ functioning

ysis of covariance approach to adjust for covariates in the community.

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014 1255

Long-Term Outcomes of the HOPES Intervention

approach (F(2,151) ¼ 5.10, p ¼ 0.007). Next, we

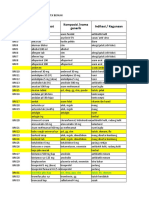

TABLE 1. Sample Characteristics by Group at Baseline

conducted independent tests on each of the three

Total Sample TAU HOPES dependent variables showing significant differences

(N [ 183) (N [ 93) (N [ 90)

favoring HOPES over TAU for participant self-report,

Characteristic N % N % N %

observed functioning in the community, and perfor-

Age, y (mean $ SD) 60.2 $ 7.9 60.1 $ 7.1 60.3 $ 8.0 mance on standardized simulated tasks. HOPES

Days in hospital 20.7 $ 39.6 21.1 $ 45.1 20.2 $ 31.1

(mean $ SD) contributed to greater overall self-efficacy compared

Gender with TAU. In testing for interactions by diagnostic

Female 106 58 53 57 53 59

group, we found that improved self-efficacy was

Male 77 42 40 43 37 41

Ethnicity greatest among participants with mood disorders.

White 157 86 78 84 79 88 No other interactions between group and diagnosis

Non-white 26 14 15 16 11 12

Latino

were observed for any other outcome variables. For

No 171 93 88 95 83 92 psychiatric symptoms, we compared both groups on

Yes 12 7 5 5 7 8 the primary outcome of overall psychiatric symptom

Marital status

Never married 118 65 59 63 59 66 severity (i.e., Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale total) and

Married 65 35 34 37 31 34 found lower overall symptom severity for HOPES.

Education We then separately evaluated primary symptom

High school 134 73 64 69 70 78

graduate outcomes between groups, finding lower negative

Less than high 49 27 29 31 20 22 symptom severity and a trend for lower depression

school

Residential

among HOPES participants. At the 3-year follow-up,

Living 94 51 49 53 45 50 no significant differences were found between groups

independently for behavior or mental/physical functioning

Supervised/ 89 49 44 47 45 50

supported outcomes as measured by the SF-36 or with respect

housing to medical severity or total number of medical

Medical diagnosis conditions.

Hypertension 80 44 47 51 33 37

Diabetes 50 27 23 25 27 30

COPD 42 23 23 25 19 21

Hypothyroidism 32 18 18 19 14 16 Preventive Healthcare Screening and Advanced

Asthmaa 25 14 7 8 18 20 Directives

Cardiac disease 23 13 14 15 9 10

Psychiatric diagnosis Table 4 compares HOPES with TAU with respect

Schizoaffective 52 28 28 30 24 27

Schizophrenia 51 28 26 28 25 28

to preventive healthcare across three categories of

Depression 44 24 20 22 24 27 indicators: (1) routine preventive care (blood pres-

Bipolar 36 20 19 20 17 19 sure, eye examination, visual acuity test, hearing test,

Notes: SD: standard deviation; COPD: chronic obstructive serum cholesterol, flu shot), (2) cancer screening

pulmonary disease.

a

(colon cancer, mammogram, Pap smear), and (3)

Fisher’s two-sided exact test ¼ 6.03; p ¼ 0.017; no other

comparisons were significant at p #0.05.

advance directives. A higher percentage of HOPES

participants received eye exams, visual acuity, and

hearing tests compared with TAU, with the greatest

between-group difference found for receipt of

Functioning, Symptom, and Health Status

mammograms and Pap smears (NNT ¼ 5.5 and 3.5,

Outcomes

respectively). Finally, a nearly twofold difference was

Tables 2 and 3 show results of the intent-to-treat found between HOPES and TAU for completing

analyses of outcomes for community functioning, advance directives (NNT ¼ 3.6). Excluding the rela-

psychiatric symptoms, and health status at the 1-, 2- tionship between female gender and mammograms

and 3-year follow-up. HOPES compared with TAU or Pap smears, there were no other gender differences

was associated with greater improvement in the with respect to receipt of the different preventive

weighted combination of the three approaches to healthcare screens or completion of advanced direc-

measuring community living skills using the multi- tives. We also explored possible interactions between

variate repeated measures analysis of variance years of education, cognitive status, and receipt of

1256 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014

Bartels et al.

preventive healthcare screens or advanced directives,

0.033

0.024

0.014

0.190

0.010

p

and no significant relationship emerged.

Group Main Effect

1, 161

1, 150

1, 163

1, 162

1, 156

df

Acute Health Service Use

Greater decreases were observed from baseline to

4.64

5.23

6.13

1.73

6.85

F

the 3-year follow-up for HOPES compared with TAU

with respect to the proportion of participants who

0.25

0.26

0.27

%0.08

0.33

had at least one psychiatric hospitalization, medical

ES

hospitalization, or emergency room visit, although

these differences were not statistically significant. The

0.11

0.14

0.44

0.48

15.15

19.48

10.06

10.39

15.89

21.08

SD

proportion of participants experiencing at least one

3 Year

acute psychiatric hospitalization decreased 7% for

Mean

0.68

0.62

3.83

3.72

77.77

70.30

48.56

50.29

72.20

69.45

HOPES compared with 3% for TAU (HOPES: 22%

[N ¼ 17] at baseline and 15% [N ¼ 11] at the 3-year

follow-up; TAU: 26% [N ¼ 22] at baseline and 23%

0.11

0.12

0.51

0.53

14.35

21.06

8.41

9.58

16.37

18.49

SD

[N ¼ 16] at the 3-year follow-up). The proportion of

2 Year

participants experiencing at least one acute medical

Mean

0.68

0.65

3.78

3.61

77.32

69.44

46.74

49.14

71.46

71.33

hospitalization decreased by 3% for HOPES

compared with an increase of 3% for TAU (HOPES:

0.09

17.70

0.11

0.45

0.50

13.47

19.88

8.54

9.23

17.74

30% [N ¼ 24] at baseline and 27% [N ¼ 20] at the

SD

TABLE 2. Community Functioning Outcomes at 3-Year Follow-Up in HOPES Compared with TAU

3-year follow-up; TAU: 27% [N ¼ 23] at baseline and

1 Year

30% [N ¼ 21] at the 3-year follow-up). Finally, there

Mean

0.68

71.35

0.66

3.76

3.58

76.04

68.97

49.30

50.75

68.76

was a 14% decrease in the proportion of participants

experiencing at least one emergency room visit for

0.10

19.16

0.11

0.51

0.51

15.93

19.04

8.94

7.97

18.61

HOPES compared with a 5% decrease for TAU

SD

Baseline

(HOPES: 55% [N ¼ 43] at baseline and 41% [N ¼ 31]

at the 3-year follow-up; TAU: 49% [N ¼ 42] at base-

Mean

0.66

66.24

0.65

3.66

3.69

72.85

68.54

51.42

51.17

68.99

line and 44% [N ¼ 31] at the 3-year follow-up).

Group

HOPES

HOPES

HOPES

HOPES

HOPES

TAU

TAU

TAU

TAU

TAU

DISCUSSION

Case manager/clinician

Participant interview/

Participant interview

Participant interview

Performance-based

Participation in HOPES was associated with

observation

observation

Data Source

improved community living skills at the 3-year

follow-up from three perspectives: participant self-

Notes: SD: standard deviation; ES: effect size.

report, case manager observation of functioning in

the community, and performance on simulated tasks

of independent living skills. HOPES contributed to

greater self-efficacy and to decreased overall severity

Self-reported: Independent Living

Self-efficacy: Revised Self-Efficacy

Performance Skills Assessment

Social behaviors: Social Behavior

Community Ability Scale total

of psychiatric and negative symptoms. These results

Simulated performance: UCSD

Social behaviors and self-efficacy

Observed functioning in the

demonstrate the persistence of improved outcomes at

community: Multnomah

Skills Survey (ILSS total)

1-year post-intervention. Integrated preventive

Community living skills

Scale (R-SES total)

Survey (SBS total)

healthcare was also associated with greater receipt of

preventive health screening and greater completion

(UPSA total)

of advanced directives.

These results contribute to a limited empirical

Measures

research literature, including the FAST and CBSST

programs. These interventions focus on middle-aged

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014 1257

Long-Term Outcomes of the HOPES Intervention

and older adults with schizophrenia and do not

0.936

HOPES 46.90 11.56 45.54 11.97 47.94 12.22 46.09 13.25 0.07 0.12 1, 159 0.732

0.048

0.053

0.073

HOPES 3.03 2.49 2.77 2.48 2.72 2.52 2.73 2.43 %0.22 0.26 1, 156 0.614

HOPES 5.48 3.99 8.55 5.44 8.78 4.68 10.43 8.42 %0.14 0.10 1, 94 0.749

P

include an integrated component of preventive

Group Main Effect

healthcare management. FAST is a 6-month interven-

11.86 0.05 0.01 1, 159

13.75 %0.17 3.97 1, 157

0.64 %0.27 3.70 1, 155

11.64 %0.22 3.26 1, 158

df

tion to improve skills for independent living,

communication, and psychiatric illness manage-

F

ment.10 In a randomized trial (N ¼ 240), FAST was

associated with greater improvement compared with

ES

usual care in negative symptoms and in performance

14.98

0.65

14.27

14.88

TAU 47.04 11.79 46.83 11.02 47.26 11.76 48.50 11.73

2.30 2.13 2.54 2.36 2.41 2.34 2.22 2.04

5.84 3.77 8.07 6.00 10.14 7.68 13.17 9.81

of community living skills.11 CBSST is a 3-month

SD

3 Year

intervention combining cognitive behavioral therapy

Mean

41.99

19.52

50.53

49.92

2.21

2.50

19.43

41.99

(e.g., cognitive restructuring) with social skills

training.11 A randomized trial (N ¼ 76) found that

10.61

10.68

13.84

13.75

13.27

0.55

0.65

13.18

SD

CBSST contributed to greater improvement in

2 Year

6-month outcomes for insight and on the leisure and

Mean

40.65

12.38

50.43

51.09

2.26

2.52

19.59

42.93

transportation subscales of the Independent Living

Skills Survey,23 but, in contrast to HOPES, no differ-

11.42

11.86

12.34

13.66

0.49

0.57

11.42

13.11

SD

TABLE 3. Psychiatric Symptoms and Health Status Outcomes at 3-Year Follow-Up in HOPES Compared with TAU

1 Year

ences were found between groups in the total scores

for living skills.8 Our 3-year findings from the current

Mean

41.77

20.01

52.82

54.34

2.29

2.51

20.63

41.27

study suggest that skills training can result in sus-

tained improvements in psychosocial functioning and

11.38

12.99

13.86

12.75

0.54

0.54

12.82

13.81

SD

Baseline

symptom severity for a heterogeneous group of older

Group Mean

38.99

23.85

55.54

54.23

2.42

2.50

20.83

41.25

adults with SMI.

In addition to achieving improved functioning and

HOPES

HOPES

HOPES

HOPES

decreased psychiatric symptoms, HOPES partici-

TAU

TAU

TAU

TAU

TAU

TAU

pants compared with TAU experienced greater

preventive healthcare screening. It is noteworthy that

Participant interview/medical records

Participant interview/observation

Participant interview/observation

the greatest improvement was found for mammo-

grams, Pap smears, and advance care planning.

Participant interview

Participant interview

Participant interview

Medical records

However, we did not observe greater improvement

Data Source

in subjective health status (as measured by the SF-36)

or lower ratings of medical severity. Of interest, the

number of identified medical diseases approximately

doubled (rather than decreased) for both HOPES and

TAU over the 3-year period of study, most likely

reflecting the impact of increased attention to

comorbid medical disorders resulting from repeated

Negative symptoms: Scale for the Assessment of

Physical functioning: SF-36 Physical Component

Notes: SD: standard deviation; ES: effect size.

Psychiatric symptoms: Brief Psychiatric Rating

participant interviews, clinician ratings, and requests

Depression: Center for Epidemiologic Studies

Mental functioning: SF-36 Mental Component

for primary care medical records. Finally, decreases

Medical severity: Charlson Severity Index

in the proportion of participants who were hospital-

Negative Symptoms (SANS total)

ized or who had an emergency room visit were

Depression Scale (CES-D total)

greater for HOPES compared with TAU, although

the sample size may not have been adequate to

Total number of diseases

demonstrate statistically significant differences.

Scale (BPRS total)

Score (MCS total)

Several limitations warrant consideration when

Psychiatric symptoms

Score (PCS total)

interpreting the results. First, our study sample was

predominantly white (86%; N ¼ 157), suggesting the

Health status

need to evaluate HOPES in diverse populations and to

Measures

explore the need for cultural adaptations.41 A version

of HOPES tailored for African Americans, developed

1258 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014

Bartels et al.

TABLE 4. Preventive Healthcare, Screening, and Advance Directives at 3-Year Follow-Up in HOPES Compared with TAUa

HOPES TAU

(N [ 90) (N [ 93)

Preventive Healthcare and Advance Directives N % N % NNT Effect Size c2 Testb p

Routine preventive care

Blood pressure 87 100 89 99 90.9 0.00 1.00 0.508

Eye exam 84 97 79 88 11.2 0.36 4.96 0.048

Visual acuity test 74 85 65 72 7.8 0.32 4.39 0.045

Hearing test 52 60 40 44 6.5 0.32 4.18 0.051

Cholesterol 84 97 84 93 30.3 0.13 0.97 0.497

Flu shot 75 86 68 76 9.4 0.26 3.28 0.087

Cancer screening

Colon cancer screen 71 82 76 84 %35.7c %0.07 0.25 0.690

Mammogram (women) 45 85 34 67 5.5 0.43 4.81 0.039

Pap smear (women) 41 77 25 49 3.5 0.59 9.16 0.004

Care planning

Advance directives 51 61 28 33 3.6 0.59 13.20 <0.001

a

Percent receiving preventive healthcare screening at least once over the 3-year study period and presence of documented advance

directives.

b

Fisher’s two-sided Exact Test.

c

Because a slightly greater proportion of TAU participants received colon cancer screening compared with HOPES participants, the NNT is

a negative value, more appropriately interpreted as number needed to harm.

after this trial, is now available. Second, because standards on clinical significance have not been

HOPES consists of both skills training and preventive established. However, the UCSD Performance-based

healthcare, we are unable to attribute the study Skills Assessment has an established cutoff for clini-

outcomes to either component. Third, the nurse cally significant improvement in functioning: a score

component emphasized preventive healthcare and of at least 75 is predictive of residential indepen-

healthcare coordination. We found improved quality dence.42 At the 3-year follow-up, two-thirds of

of preventive healthcare (a proximal outcome) but did HOPES participants achieved at least 75 on the UCSD

not demonstrate significant improvement in health Performance-based Skills Assessment (67%; N ¼ 37)

status (a distal outcome) as measured by the SF-36. compared with slightly more than half of those

More targeted disease management (as opposed to receiving TAU (54%; N ¼ 30) (NNT ¼ 7.3).

general care coordination) and a longer follow-up These findings advance the evidence base on

period may be needed to demonstrate improved effective interventions for older adults with SMI in

health outcomes. several ways. Our study demonstrates the feasibility

In addition, because HOPES consists of seven and effectiveness of integrating group-based skills

discrete modules delivered over 1 year followed by training and preventive healthcare targeting older

a second year of monthly booster sessions, our study adults with SMI. An important strength was that

was not designed to assess the comparative or HOPES demonstrated improved independent living

incremental contributions of the individual modules skills and community functioning from multiple

to improved outcomes. A more targeted and indi- perspectives including self-report, case manager

vidually tailored approach may be more effective and observation, and role-play assessments of skills. We

efficient. We are currently engaged in pilot studies also found that integrated preventive healthcare

exploring the feasibility and potential effectiveness of coordination by an embedded nurse can significantly

matching participant need and preference for improve adherence to preventive screening, especially

selected components of HOPES. Finally, although we for procedures such as mammograms and Pap

found statistically significant improvements on smears, in addition to substantially improving

several measures of functioning and symptoms over advance care planning. Finally, HOPES participants

3 years, the clinical significance of these improve- maintained gains in improved functioning and

ments is uncertain. For most of the measures, symptoms at the 3-year follow-up. To our knowledge,

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014 1259

Long-Term Outcomes of the HOPES Intervention

this improvement in functioning provides the longest between science and services provided in the

and largest demonstration of the effectiveness of community. To respond to the rapidly growing

psychosocial skills training for persons with SMI, population of older adults with SMI, a future

regardless of age group. research agenda should include identifying success-

There are several potential implications of these ful strategies for implementing and sustaining effec-

findings. First, as underscored by the 2012 Institute of tive integrated rehabilitation and healthcare services

Medicine Report on the mental health workforce for in the community.

older adults,5 the burgeoning population of older

adults with SMI will require more providers trained The authors thank the following individuals for their

to supply evidence-based practices for this high-risk assistance in conducting this project: Kay Allen, Therese

group.43 HOPES adds to the small number of Andrews, Rachel Berman, Sarah Bishop-Horton, Alice

psychosocial interventions validated for use among Cassidy, Sara Castillo, Martha Curtis, Vanessa D’Anna,

older adults with SMI8,11 and confirms that the Meghan Driscoll, Carol Farmer, Susan Fitzpatrick, Anne

effectiveness of psychosocial rehabilitation is not Fletcher, Carol Furlong, Severina Haddad, Carol Johnson,

limited to younger adults. These interventions may Sarah Kelly, Lisa Kennedy, Meghan Santos, Cynthia

also provide a strategy for responding to the U.S. Meddich, Katie Merrill, Krystal Murray, Brenda Nick-

Supreme Court Olmstead Decision mandating that erson, Thomas Patterson, Reni Poulakos, Christina Riggs,

states provide services supporting the preference of Brenda Wilbert, Joanne Wojcik, and Valerie Zelonis.

adults with disabilities to reside in noninstitutional The study was supported by a grant from the National

settings.2 Finally, there remains a dramatic gap Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH62324).

References

1. Bartels SJ, Miles KM, Dums AR, et al: Factors associated with 10. Patterson TL, McKibbin C, Taylor M, et al: Functional Adaptation

community mental health service use by older adults with severe Skills Training (FAST): a pilot psychosocial intervention study in

mental illness. J Mental Health Aging 2003; 9:123e135 middle-aged and older patients with chronic psychotic disorders.

2. Bartels SJ: Commentary: the forgotten older adult with serious Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:17e23

mental illness: the final challenge in achieving the promise of 11. Patterson TL, Mausbach BT, McKibbin C, et al: Functional

Olmstead? J Aging Soc Policy 2011; 23:244e257 Adaptation Skills Training (FAST): a randomized trial of

3. U.S. Census Bureau: National Population Projections Released a psychosocial intervention for middle-aged and older patients

2008: Table 12: Projections of the Population by Age and Sex for with chronic psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res 2006; 86:

the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC, U.S. Census 291e299

Bureau, 2008 12. Bartels SJ, Clark RE, Peacock WJ, et al: Medicare and Medicaid

4. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: costs for schizophrenia patients by age cohort compared with

MedTEAM: How to Use the Evidence-Based Practices KITs. costs for depression, dementia, and medically ill patients. Am J

Rockville, MD, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:648e657

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Depart- 13. Bartels SJ, Miles KM, Dums AR, et al: Are nursing homes appro-

ment of Health and Human Services, 2010 priate for older adults with severe mental illness? Conflicting

5. Institute of Medicine: The Mental Health and Substance Use consumer and clinician views and implications for the Olmstead

Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands?. Washington, DC, decision. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:1571e1579

The National Academies Press, 2012 14. Hendri HC, Lindgren D, Hay DP, et al: Comorbidity profile and

6. Granholm E, Holden J, Link PC, et al: Randomized controlled trial healthcare utilization in elderly patients with serious mental

of cognitive behavioral social skills training for older consumers illnesses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:1267e1276

with schizophrenia: defeatist performance attitudes and func- 15. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al: Quality of preventive

tional outcome. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:251e262 medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care 2002;

7. Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, et al: Randomized 40:129e136

controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for 16. Bartels SJ, Forester B, Mueser KT, et al: Enhanced skills training

older people with schizophrenia: 12-month follow-up. J Clin and health care management for older persons with severe

Psychiatry 2007; 68:730e737 mental illness. Commun Mental Health J 2004; 40:75e90

8. Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, et al: A randomized, 17. Pratt SI, Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, et al: Helping Older People

controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for Experience Success: an integrated model of psychosocial

middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. rehabilitation and health care management for older adults

Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:520e529 with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2008; 11:

9. Berry K, Purandare N, Drake R, et al: A mixed-methods evaluation 41e60

of a pilot psychosocial intervention group for older people with 18. Mueser KT, Pratt SI, Bartels SJ, et al: Randomized trial of

schizophrenia. Behav Cogn Psychother 2014; 42:199e210 social rehabilitation and integrated health care for older

1260 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014

Bartels et al.

people with severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol instrument for depression among community-residing older

2010; 78:561e573 adults. Psychol Aging 1997; 12:277e287

19. Pratt SI, Mueser KT, Bartels SJ, et al: The impact of skills training 31. Ware JE Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al: SF-36 Health Survey

on cognitive functioning in older people with serious mental Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA, The Health Insti-

illness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:242e250 tute, New England Medical Center, 1997

20. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Inter- 32. Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, et al: A new method of classifying

view for DMS-IV Axis-I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and

Version 2.0). New York, Biometrics Research Department, 1996 validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373e383

21. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: Mini-mental state: a prac- 33. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Recommendations for

tical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the Adults. Rockville, MD, USPSTF Program Office, 2013

clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189e198 34. Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J: Applied Longitudinal Analysis.

22. Bellack AS: Skills training for people with severe mental illness. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2004

Psychiatr Rehabil J 2004; 27:375e391 35. Hedeker D, Gibbons RD: Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York,

23. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, et al: The Independent Living Wiley, 2006

Skills Survey: a comprehensive measure of the community func- 36. Jennrich R, Schluchter M: Unbalanced repeated-measures models

tioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. with structured covariance matrices. Biometrics 1986; 42:

Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:631e658 805e820

24. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al: A community ability 37. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences,

scale for chronically mentally ill consumers: part I. reliability and 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988

validity. Commun Mental Health J 1994; 30:363e379 38. Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF: Effect sizes for interpreting

25. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, et al: USCD Performance- changes in health status. Med Care 1989; 27:S178eS189

based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of 39. Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS: An assessment of clinically

everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med

Bull 2001; 27:235e245 1988; 318:1728e1733

26. Wykes T, Sturt E: The measurement of social behaviour in 40. Crowther RE, Marshall M, Bond GR, et al: Helping people with

psychiatric patients: an assessment of the reliability and validity severe mental illness to obtain work: systematic review. BMJ

of the SBS Schedule. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 148:1e11 2001; 322:204e208

27. McDermott BE: Development of an instrument for assessing self- 41. Patterson TL, Bucardo J, McKibbin CL, et al: Development

efficacy in schizophrenic spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychol and pilot testing of a new psychosocial intervention for older

1995; 51:320e331 Latinos with chronic psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31:

28. Andersen J, Larsen JK, Korner A, et al: The brief psychiatric rating 922e930

scale: schizophrenia, reliability and validity studies. Nord J 42. Mausbach BT, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, et al: Usefulness of the

Psychiatry 1986; 40:135e138 UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA) for predicting

29. Andreasen NC: Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative residential independence in patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Symptoms. Bethesda, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human J Psychiatr Res 2008; 42:320e327

Services, 1984 43. Bartels SJ, Naslund JA: The underside of the silver tsunami—

30. Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, et al: Center for Epidemi- older adults and mental health care. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:

ologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening 493e496

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:11, November 2014 1261

You might also like

- Head To Toe Assessment Checklist Older Adults-1Document1 pageHead To Toe Assessment Checklist Older Adults-1spatrick32100% (4)

- ACLS Megacode Testing ScenariosDocument12 pagesACLS Megacode Testing Scenariosealm10100% (2)

- Pulp Exposure in Permanent Teeth CG-A012-04 UpdatedDocument7 pagesPulp Exposure in Permanent Teeth CG-A012-04 UpdatedmahmoudNo ratings yet

- Grandón Et Al - 2021 - Effectiveness of An Intervention To Reduce StigmaDocument9 pagesGrandón Et Al - 2021 - Effectiveness of An Intervention To Reduce StigmaAlejandra DìazNo ratings yet

- Older Adults and Integrated Health Settings: Opportunities and Challenges For Mental Health CounselorsDocument15 pagesOlder Adults and Integrated Health Settings: Opportunities and Challenges For Mental Health CounselorsGabriela SanchezNo ratings yet

- 4 Vancouver English B30Document14 pages4 Vancouver English B30aditiarrtuguNo ratings yet

- Hospitalization EditedDocument6 pagesHospitalization EditedmercyNo ratings yet

- Psychological and Social Interventions For Mental Health Issues and Disorders in Southeast Asia: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesPsychological and Social Interventions For Mental Health Issues and Disorders in Southeast Asia: A Systematic ReviewMico Joshua OlorisNo ratings yet

- Marinucci Et Al. - 2023 - A Scoping Review and Analysis of Mental Health LitDocument16 pagesMarinucci Et Al. - 2023 - A Scoping Review and Analysis of Mental Health Litreeba khanNo ratings yet

- Igx004 2993Document1 pageIgx004 2993Arifah Budiarti NurfitriNo ratings yet

- FWD - Mixed Anxiety and Depression Among The Adult Population of The UK.Document8 pagesFWD - Mixed Anxiety and Depression Among The Adult Population of The UK.Sonal PandeyNo ratings yet

- Population-Health Approach: Mental Health and Addictions SectorDocument5 pagesPopulation-Health Approach: Mental Health and Addictions SectorNilanjana ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dyadic Psychological InterventionsDocument22 pagesA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dyadic Psychological InterventionsCristina MPNo ratings yet

- Fernandez 2022 Smartphone Famliy ConnectionsDocument7 pagesFernandez 2022 Smartphone Famliy ConnectionsBrayan PomaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health and Coping Strategies of Private Secondary School Teachers in The New Normal: Basis For A Psycho-Social Wellbeing Developmental ProgramDocument18 pagesMental Health and Coping Strategies of Private Secondary School Teachers in The New Normal: Basis For A Psycho-Social Wellbeing Developmental ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- JengMun - 2023 - Development of Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Workshop Protocol MalaysiaDocument11 pagesJengMun - 2023 - Development of Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Workshop Protocol Malaysiags67461No ratings yet

- Digital Mental Health Clinic in Secondary SchoolsDocument11 pagesDigital Mental Health Clinic in Secondary Schoolssoyjeric3266No ratings yet

- Betts2018 Article APsychoeducationalGroupInterveDocument7 pagesBetts2018 Article APsychoeducationalGroupInterveCralosNo ratings yet

- Hearing LossDocument10 pagesHearing LossAndreaNo ratings yet

- Ann 18 04 07Document8 pagesAnn 18 04 07EuNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Literacy, Level of Stressful Experiences and Coping Strategies of Elementary School TeachersDocument15 pagesMental Health Literacy, Level of Stressful Experiences and Coping Strategies of Elementary School TeachersPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-584310341No ratings yet

- Understanding The Relationships Between Mental Disorders, Self-Reported Health Outcomes and Positive Mental Health: Findings From A National SurveyDocument10 pagesUnderstanding The Relationships Between Mental Disorders, Self-Reported Health Outcomes and Positive Mental Health: Findings From A National SurveyHung TranNo ratings yet

- Fisher 2017Document6 pagesFisher 2017Bogdan NeamtuNo ratings yet

- Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2020 29 1 211-23Document13 pagesChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2020 29 1 211-23Fernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Collaboration Among The Education, Mental Health, and Public Health Systems To Promote Youth Mental HealthDocument4 pagesCollaboration Among The Education, Mental Health, and Public Health Systems To Promote Youth Mental HealthKouseiNo ratings yet

- A Psychoeducational Group Intervention For FamilyDocument8 pagesA Psychoeducational Group Intervention For FamilyIoannis MalogiannisNo ratings yet

- Lay CounselorDocument12 pagesLay Counselornurul cahya widyaningrumNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Literacy Programs For School Teachers: A Systematic Review and Narrative SynthesisDocument12 pagesMental Health Literacy Programs For School Teachers: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesisnefe_emeNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care Nurses Attitude Towards People With Severe Mental Disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional StudyDocument8 pagesPrimary Health Care Nurses Attitude Towards People With Severe Mental Disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional StudyleticiaNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness Based Interventions For People With Dementia and Their Caregivers Keeping A Dyadic BalanceDocument4 pagesMindfulness Based Interventions For People With Dementia and Their Caregivers Keeping A Dyadic BalanceMile RojasNo ratings yet

- Minding The Treatment Gap: Results of The Singapore Mental Health StudyDocument10 pagesMinding The Treatment Gap: Results of The Singapore Mental Health StudyNicholasNo ratings yet

- Research Paper ReviewDocument14 pagesResearch Paper ReviewGnaneswar PiduguNo ratings yet

- Jacm 03.2011Document6 pagesJacm 03.2011Meek ElNo ratings yet

- Examination of Telemental Health Practices in Caregivers of Children and Adolescents With Mental Illnesses A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesExamination of Telemental Health Practices in Caregivers of Children and Adolescents With Mental Illnesses A Systematic ReviewMushlih RidhoNo ratings yet

- TESTDocument11 pagesTESTANKITA YADAVNo ratings yet

- Peerj 4598Document27 pagesPeerj 4598David QatamadzeNo ratings yet

- Effects of The Tailored Activity ProgramDocument14 pagesEffects of The Tailored Activity ProgramBarbara Aguilar MaulenNo ratings yet

- 1Document13 pages1Erika HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Behaviour Research and TherapyDocument11 pagesBehaviour Research and TherapyCata PazNo ratings yet

- Addressing Mental Health in Aged Care ResidentsDocument9 pagesAddressing Mental Health in Aged Care ResidentsCarlos Hernan Castañeda Ruiz100% (1)

- Psychosocial Interventions For People With Dementia: An Overview and Commentary On Recent DevelopmentsDocument28 pagesPsychosocial Interventions For People With Dementia: An Overview and Commentary On Recent DevelopmentsMahendra SusenoNo ratings yet

- JurnalkepjiwaaDocument21 pagesJurnalkepjiwaaDewi AgustianiNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J Ejb 20190702 13 PDFDocument6 pages10 11648 J Ejb 20190702 13 PDFfitriNo ratings yet

- Asia-Pacific Psychiatry - 2020 - Ismail - The Prevalence of Psychological Distress and Its Association With CopingDocument8 pagesAsia-Pacific Psychiatry - 2020 - Ismail - The Prevalence of Psychological Distress and Its Association With CopingbellaajsarraNo ratings yet

- Tugas 1Document10 pagesTugas 1Siti QomariaNo ratings yet

- 2023 Article 426Document23 pages2023 Article 426Kiran AbbasNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 18 00314Document15 pagesIjerph 18 00314Afifah Az-ZahraNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of CMHN (Community Mental Health Nursing) To Improve Mental Health in The Community - A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness of CMHN (Community Mental Health Nursing) To Improve Mental Health in The Community - A Systematic Reviewfanizha apriliantiNo ratings yet

- Art in InquiryDocument13 pagesArt in InquiryEmmanuel Emma NdikuryayoNo ratings yet

- Mobile Health (Mhealth) Versus Clinic-Based Group Intervention For People With Serious Mental Illness: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument8 pagesMobile Health (Mhealth) Versus Clinic-Based Group Intervention For People With Serious Mental Illness: A Randomized Controlled TrialOlivia NasarreNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With The Burden of Family Caregivers of Patients With Mental Disorders: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument10 pagesFactors Associated With The Burden of Family Caregivers of Patients With Mental Disorders: A Cross-Sectional StudyKrishna RaoNo ratings yet

- Clinical Efficacy of A Combined AcceptanDocument16 pagesClinical Efficacy of A Combined AcceptanEmanuel EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Harris Et Al., 2013 (BA - Depression - Physical Illness)Document6 pagesHarris Et Al., 2013 (BA - Depression - Physical Illness)Alba EneaNo ratings yet

- Reyes-Ortega 2019 ACT or DBT or Both - With Borderline Personality DisorderDocument16 pagesReyes-Ortega 2019 ACT or DBT or Both - With Borderline Personality DisorderMario Lopez PadillaNo ratings yet

- Early Intervention Psych - 2019 - Courtney - A Way Through The Woods Development of An Integrated Care Pathway For 1Document9 pagesEarly Intervention Psych - 2019 - Courtney - A Way Through The Woods Development of An Integrated Care Pathway For 1U of T MedicineNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Therapeutic Intervention Program On The Socio-Emotional Development of Persons With Substance Use DisorderDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of The Therapeutic Intervention Program On The Socio-Emotional Development of Persons With Substance Use DisorderPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Ref 2 India Mental HealthDocument7 pagesRef 2 India Mental Healthdnyanesh1inNo ratings yet

- Bài 3Document2 pagesBài 3Quỳnh Như Nguyễn TrịnhNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Valued Living As Critical Appraisal and Coping Strengths For Caregivers Dealing With Terminal Illness and BereavementDocument10 pagesAcceptance and Valued Living As Critical Appraisal and Coping Strengths For Caregivers Dealing With Terminal Illness and BereavementPaula Catalina Mendoza PrietoNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Online "DDocument14 pagesEffectiveness of The Online "DdewisimooNo ratings yet

- Population-Based Approaches To Mental Health: History, Strategies, and EvidenceDocument28 pagesPopulation-Based Approaches To Mental Health: History, Strategies, and EvidenceMatías Muñoz L.No ratings yet

- Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse The Effects On Mental Health And The Role Of Cognitive Behavior TherapyFrom EverandAdult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse The Effects On Mental Health And The Role Of Cognitive Behavior TherapyNo ratings yet

- BAT and KCL Study ProposalDocument4 pagesBAT and KCL Study ProposalAnuNo ratings yet

- Pocket-Book MCH Emergencies - English PDFDocument286 pagesPocket-Book MCH Emergencies - English PDFAbigail Kusi-Amponsah100% (1)

- DR Antonious CV N & AEDocument27 pagesDR Antonious CV N & AEdoctorantoniNo ratings yet

- 4th Year Write Up 2 - Int. MedDocument11 pages4th Year Write Up 2 - Int. MedLoges TobyNo ratings yet

- EXAMEN - 3EPPLI 30i+RFMHS 6 PDFDocument13 pagesEXAMEN - 3EPPLI 30i+RFMHS 6 PDFS Lucy PraGaNo ratings yet

- Hand Hygiene in Dental Health-Care SettingsDocument55 pagesHand Hygiene in Dental Health-Care SettingsManu DewanNo ratings yet

- Male InfertilityDocument38 pagesMale InfertilityPrincessMagnoliaFranciscoLlantoNo ratings yet

- PNSS Drug StudyDocument2 pagesPNSS Drug Studyrain peregrinoNo ratings yet

- Hepatic Dysfunction in Dengue Fever - A ProspectiveDocument20 pagesHepatic Dysfunction in Dengue Fever - A ProspectiveSanjay RaoNo ratings yet

- Rectovaginal FistulaDocument8 pagesRectovaginal FistulaRomi Mauliza FauziNo ratings yet

- BVCCT-501 Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory BasicsDocument52 pagesBVCCT-501 Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory BasicsManisha khan100% (1)

- Obs Exam QuestionsDocument265 pagesObs Exam Questionsreza_adrian_2100% (2)

- KodingDocument12 pagesKodingAva Vav100% (1)

- DRUG STUDY Setera Case 8Document10 pagesDRUG STUDY Setera Case 8Ceria Dorena Fe SeteraNo ratings yet

- Role of Atypical Pathogens in The Etiology of Community-Acquired PneumoniaDocument10 pagesRole of Atypical Pathogens in The Etiology of Community-Acquired PneumoniaJaya Semara PutraNo ratings yet

- Gait AnalysisDocument2 pagesGait AnalysisIvin KuriakoseNo ratings yet

- Beta Lactam AntibioticsDocument52 pagesBeta Lactam AntibioticsKaymie ReenNo ratings yet

- Specialize Immunity at Epithelial Barriers and in Immune Privilege TissuesDocument27 pagesSpecialize Immunity at Epithelial Barriers and in Immune Privilege TissuesUmar UsmanNo ratings yet

- 901-Article Text-1856-1-10-20221129Document6 pages901-Article Text-1856-1-10-20221129Made NujitaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Understanding The Essentials of Critical Care Nursing 2nd Edition by PerrinDocument15 pagesSolution Manual For Understanding The Essentials of Critical Care Nursing 2nd Edition by PerrinMarieHughesebgjp100% (75)

- Nama Obat Indikasi / Kegunaan Komposisi /nama Generik: Brochifar Plus Kap PCT, DMP, Ppa, CTM Batuk, Flu, DemamDocument52 pagesNama Obat Indikasi / Kegunaan Komposisi /nama Generik: Brochifar Plus Kap PCT, DMP, Ppa, CTM Batuk, Flu, Demamrio1995No ratings yet

- Non-Modifiable Risk Factors: Hepatoblastoma CaseDocument1 pageNon-Modifiable Risk Factors: Hepatoblastoma CaseALYSSA AGATHA FELIZARDONo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Assasination (Partial)Document14 pagesPharmaceutical Assasination (Partial)jamie_clark_2100% (2)

- Pain Management in ChildrenDocument19 pagesPain Management in ChildrenNeo SamontinaNo ratings yet

- Ventouse - FinalDocument10 pagesVentouse - FinalJasmine KaurNo ratings yet

- Hyperemesis GravidarumDocument7 pagesHyperemesis GravidarumPrawira Weka AkbariNo ratings yet

- DrugsDocument2 pagesDrugsJeff MarekNo ratings yet