Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Manajemen Operasional Stratejik 5th

Uploaded by

KN STORYCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Manajemen Operasional Stratejik 5th

Uploaded by

KN STORYCopyright:

Available Formats

Are the four perspectives of operations strategy reconciled?

67

A company that has position A in Figure 2.11 has achieved ‘fit’ in so much as its operations

capabilities are aligned with its market requirements, yet both are at a relatively low level. In

other words, the market does not want much from the business, which is just as well because

its operation is not capable of achieving much. Over time its ambition is to move to position D,

where it has also achieved ‘fit’, but at a much higher level. Other things being equal, this will

be a more profitable position that position A.

However, like most strategic improvement, the company cannot always guarantee to keep

on the ‘line of fit’ as it moves from A to D over time. In this case, it first improves its operations

capability without exploiting its enhanced capability in its market (position B). This could be

seen as a ‘waste’ of its potential to adopt a more ambitious (and possibly profitable) market

position. Realising this, the company revises its marketing strategy to promote itself as being

able to maintain a much higher level of market performance (position C). Unfortunately, these

new promises to its market are not matched by its operations capabilities. The company is again

away from the line of fit. In fact, position C is possibly even more damaging than position B.

The risk now is that the company’s market reputation will erode until it can improve its opera-

tions capabilities to bring it back to the line of fit (position D).

The issue that is highlighted by positioning operations strategy relative to the line of fit is

that progress cannot always be a smooth trajectory that achieves perfect balance between

market requirements and operations capability. Furthermore, when an operation deviates from

the line of fit there are predictable consequences. A position below the line of fit means that

the operation is failing to exploit its operations capabilities. A position above the line of fit

means that it risks damaging its reputation or brand by failing to live up to its market

promises.

EXAMPLE Nokia, a failure to change16

Only a decade ago, Nokia was the king of the mobile phone business – and it was a good busi-

ness to be in, with double-digit growth year on year. Nokia was omnipresent and omnipowerful,

a pioneer that had supplied the first mass wave of the expanding mobile phone industry. They

dominated the market in many parts of the world and the easily recognisable Nokia ring-tone

echoed everywhere from boardrooms to shopping malls. So why did this, once dominant,

company eventually sink to the point where it was forced to sell its mobile communications

business to Microsoft in 2013? The former Nokia CEO, Jormal Ollila, admitted that Nokia made

several mistakes, but the exact nature of those mistakes is a point of debate amongst business

commentators. Julian Birkinshaw, a Professor at London Business School dismisses some of the

most commonly cited reasons. Did they lose touch with their customers? Well, yes, but by defi-

nition that must hold for any company whose sales drop so drastically in the face of thriving

competitors. Did they fail to develop the necessary technologies? No. Nokia had a prototype

touchscreen before the iPhone was launched, and its smartphones were technologically superior

to anything Apple, Samsung, or Google had to offer for many years. Did they not recognise

that the basis of competition was shifting from the hardware to the ecosystem? (A technology

ecosystem in this case is a term used to describe the complex system of interdependent com-

ponents that work together to enable mobile technology to operate successfully.) Not really.

The ‘ecosystem’ battle began in the early 2000s, with Nokia joining forces with Ericsson,

Motorola and Psion to create Symbian as a platform technology that would keep Microsoft at

bay.

Where they struggled was in relying on an operations strategy that failed to allocate resources

appropriately and could not implement the changes that were necessary. As far as resource

allocation was concerned, Nokia saw itself primarily as a hardware company rather than a

software company. Its engineers were great at designing and producing hardware, but not the

programs that drive the devices. They underestimated the importance of software (including,

crucially, the apps that run on smartphones). Largely it was hardware rather than software

68 Chapter 2 Operations and strategic impact

experts who controlled its development process. By contrast, Apple had always emphasised that

hardware and software were equally important. Yet while they were losing their dominance,

Nokia were well aware of most of the changes occurring in the mobile communications market

and the technology developments being actively pursued by competitors. Arguably, they were

not short of awareness, but they did lack the capacity to convert awareness into action. The

failure of big companies to adapt to changing circumstances is one of the fundamental puzzles

in the world of business, says Professor Birkinshaw. Occasionally, a genuinely ‘disruptive’ tech-

nology can wipe out an entire industry. But usually the sources of failure are less dramatic. Often

it is a failure to implement strategies or technologies that have already been developed, an

arrogant disregard for changing customer demands, or a complacent attitude towards new

competitors.

DI AG NO S TI C Q UEST IO N

Does operations strategy set an

improvement path?

An operations strategy is the starting point for operations improvement. It sets the direction in

which the operation will change over time. It is implicit that the business will want operations

to change for the better. Therefore, unless an operations strategy gives some idea as to how

improvement will happen, it is not fulfilling its main purpose. This is best thought about in terms

of how performance objectives, both in themselves and relative to each other, will change over

time. To do this, we need to understand the concept of, and the arguments concerning, the

trade-offs between performance objectives.

An operations strategy should guide the trade-offs between performance

objectives

An operations strategy should address the relative priority of operation’s performance objec-

tives (‘for us, speed of response is more important than cost efficiency, quality is more impor-

tant than variety’, and so on). To do this it must consider the possibility of improving its

performance in one objective by sacrificing performance in another. So, for example, an

operation might wish to improve its cost efficiencies by reducing the variety of products or

services that it offers to its customers. Taken to its extreme; this ‘trade-off’ principle implies

that improvement in one performance objective can only be gained at the expense of another.

‘There is no such thing as a free lunch’ could be taken as a summary of this approach to

managing. Probably the best-known summary of the trade-off idea comes from Professor

Wickham Skinner, the most influential of the originators of the strategic approach to opera-

tions, who said:

. . . most managers will readily admit that there are compromises or trade-offs

OPERATIONS PRINCIPLE to be made in designing an airplane or truck. In the case of an airplane, trade-

In the short term, operations cannot offs would involve matters such as cruising speed, take-off and landing dis-

achieve outstanding performance in tances, initial cost, maintenance, fuel consumption, passenger comfort and

all its operations objectives cargo or passenger capacity. For instance, no one today can design a 500-

simultaneously. passenger plane that can land on an aircraft carrier and also break the sound

barrier. Much the same thing is true in . . . [operations].17

You might also like

- Network Marketing Business Plan ExampleDocument50 pagesNetwork Marketing Business Plan ExampleJoseph QuillNo ratings yet

- Tomorrow's Agile Operations: WhitepaperDocument22 pagesTomorrow's Agile Operations: WhitepaperMarj Sy100% (1)

- McKinsey Telecoms. RECALL No. 19 - Innovation and Product Development: Growth Versus CompetitionDocument68 pagesMcKinsey Telecoms. RECALL No. 19 - Innovation and Product Development: Growth Versus CompetitionkentselveNo ratings yet

- Dual Transformation: Quick GuideDocument26 pagesDual Transformation: Quick Guideaylin kadirdağ100% (1)

- AR88948-LM - The CIO Agenda For The Next 12 MonthsDocument7 pagesAR88948-LM - The CIO Agenda For The Next 12 MonthsYtalo DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Developer VelocityDocument41 pagesDeveloper VelocityWilliams TrumanNo ratings yet

- Pt. Patco Elektronik Teknologi Standard Operating Procedure PurchasingDocument8 pagesPt. Patco Elektronik Teknologi Standard Operating Procedure Purchasingmochammad iqbal100% (1)

- Solution Manual For Financial Reporting Financial Statement Analysis and Valuation 9th Edition by WahlenDocument33 pagesSolution Manual For Financial Reporting Financial Statement Analysis and Valuation 9th Edition by WahlenJames Coria100% (29)

- The Future of The Logistics IndustryDocument20 pagesThe Future of The Logistics IndustryTubagus Donny SyafardanNo ratings yet

- Ebook English in LogisticsDocument24 pagesEbook English in LogisticsAnh TranNo ratings yet

- Business Model Navigator Working Paper PDFDocument18 pagesBusiness Model Navigator Working Paper PDFLuis Fernando Quintero HenaoNo ratings yet

- The St. Gallen Business Model Navigator: Oliver Gassmann, Karolin Frankenberger, Michaela CsikDocument18 pagesThe St. Gallen Business Model Navigator: Oliver Gassmann, Karolin Frankenberger, Michaela CsikArun RaoNo ratings yet

- Kaizen: A Lean Manufacturing Tool For Continuous ImprovementDocument24 pagesKaizen: A Lean Manufacturing Tool For Continuous ImprovementSamrudhi PetkarNo ratings yet

- The ST Gallen Business Model NavigatorDocument18 pagesThe ST Gallen Business Model NavigatorOscar ManriqueNo ratings yet

- e-StatementBRImo 585401009753509 Jul2023 20230731 081457Document2 pagese-StatementBRImo 585401009753509 Jul2023 20230731 08145709. BUNGA NUR YUNITA SARINo ratings yet

- Business Model Navigator Whitepaper - 2019Document9 pagesBusiness Model Navigator Whitepaper - 2019Zaw Ye HtikeNo ratings yet

- Marketing Strategy of NokiaDocument25 pagesMarketing Strategy of NokiaVivek JainNo ratings yet

- Digital Transformation As A Path To Growth PDFDocument12 pagesDigital Transformation As A Path To Growth PDFBui Hoang GiangNo ratings yet

- Tech-Enabled TransformationDocument67 pagesTech-Enabled TransformationjhlaravNo ratings yet

- St-Gallen-The Business Model Navigator - 55 Models That Will Revolutionise Your BusinessDocument18 pagesSt-Gallen-The Business Model Navigator - 55 Models That Will Revolutionise Your BusinessAlexander Pulido MarínNo ratings yet

- 5.tender Process N DocumentationDocument35 pages5.tender Process N DocumentationDilanka MJ Dassanayake100% (1)

- Mendix Dont Get Lost in The App JungleDocument19 pagesMendix Dont Get Lost in The App JungleRajesh Prabhu RNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management June 2022 ExaminationDocument10 pagesStrategic Management June 2022 ExaminationShruti MakwanaNo ratings yet

- Neha's Strategic ManagementDocument6 pagesNeha's Strategic Managementneha bakshiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management JUNE 2022Document12 pagesStrategic Management JUNE 2022Rajni KumariNo ratings yet

- Article Summary 19M067 To 19M075Document14 pagesArticle Summary 19M067 To 19M075jyothi vaishnavNo ratings yet

- Competitor Assn - SiddhantDocument4 pagesCompetitor Assn - SiddhantAkanksha KaliaNo ratings yet

- Business-Model-EvolutionDocument22 pagesBusiness-Model-EvolutiondantieNo ratings yet

- Agile Legacy Lifecycle PDFDocument12 pagesAgile Legacy Lifecycle PDFAniil KumarNo ratings yet

- Strategic Outsourcing Opps&risks PDFDocument6 pagesStrategic Outsourcing Opps&risks PDFADITYAJDNo ratings yet

- Nokia Master ThesisDocument7 pagesNokia Master Thesisaflowlupyfcyye100% (2)

- Strategic Management FinalDocument10 pagesStrategic Management FinalKarandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Referensi WajibDocument15 pagesReferensi WajibGilang Akun2No ratings yet

- OM0018Document7 pagesOM0018chetanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Managing Innovation Within FirmsDocument23 pagesChapter 5 - Managing Innovation Within FirmsMr AyieNo ratings yet

- Clark Wheelwright The Concept of A Development StrategyDocument17 pagesClark Wheelwright The Concept of A Development StrategyLuane Tais Duarte Mendes NepomucenoNo ratings yet

- Dual TransformationDocument26 pagesDual TransformationJesusNo ratings yet

- Ntroduction: What Is Operations Management?Document10 pagesNtroduction: What Is Operations Management?salty3dogNo ratings yet

- Strategic ManagementDocument10 pagesStrategic ManagementPrema SNo ratings yet

- How Companies Become Platform LeaderDocument4 pagesHow Companies Become Platform Leaderbadal50% (2)

- Human Resource Management - Appropriateness of Organizational Structures and External FactorsDocument17 pagesHuman Resource Management - Appropriateness of Organizational Structures and External FactorsNikola BozhinovskiNo ratings yet

- 1.entry Barrier: Covid-19-Impact-By-2028Document4 pages1.entry Barrier: Covid-19-Impact-By-2028vijayadarshini vNo ratings yet

- Aligning Digital Transformation and Applications Road MapDocument9 pagesAligning Digital Transformation and Applications Road MapGabrielGarciaOrjuelaNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Company of Tomorrow - Cutter ConsortiumDocument11 pagesBecoming A Company of Tomorrow - Cutter ConsortiummtnezNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Ethics MGTDocument5 pagesAssignment 3 Ethics MGTVikash MishraNo ratings yet

- Building Resilient OperationsDocument4 pagesBuilding Resilient OperationsMiguel Angel Lopez GNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On NokiaDocument6 pagesTerm Paper On Nokiadpsjefsif100% (1)

- Various Business ModelsDocument18 pagesVarious Business ModelsvNo ratings yet

- Business Model Navigator2Document18 pagesBusiness Model Navigator2Diego Alejandro QuirogaNo ratings yet

- Operations Management in Automotive Industries: From Industrial Strategies to Production Resources Management, Through the Industrialization Process and Supply Chain to Pursue Value CreationFrom EverandOperations Management in Automotive Industries: From Industrial Strategies to Production Resources Management, Through the Industrialization Process and Supply Chain to Pursue Value CreationNo ratings yet

- The St. Gallen Business Model Navigator: Oliver Gassmann, Karolin Frankenberger, Michaela CsikDocument18 pagesThe St. Gallen Business Model Navigator: Oliver Gassmann, Karolin Frankenberger, Michaela Csikzquesada80No ratings yet

- Boxwood What Is A Technology Operating Model' and Which Should I HaveDocument4 pagesBoxwood What Is A Technology Operating Model' and Which Should I HavesolsolidNo ratings yet

- DRB Model EDocument18 pagesDRB Model ENorhazwani Najihah NoorazmiNo ratings yet

- The Art of Managing New Product TransitionsDocument11 pagesThe Art of Managing New Product TransitionsAryan AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Roland Berger TAB Lean Telco 20140731Document16 pagesRoland Berger TAB Lean Telco 20140731Shaunak DeyNo ratings yet

- Operational StrategyDocument2 pagesOperational Strategyusme314No ratings yet

- Adaptability The New Competitive AdvantageDocument12 pagesAdaptability The New Competitive AdvantageMarc BonetNo ratings yet

- BCG Classics TheoriesDocument18 pagesBCG Classics TheoriesSHALINI ARYA-IBNo ratings yet

- Irm 04Document14 pagesIrm 04Fahmid Ul IslamNo ratings yet

- What Is Lean Construction?Document3 pagesWhat Is Lean Construction?CarlosGerardinoNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Global Business Management 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Global Business Management 1diamond WritersNo ratings yet

- 6 AlishaChhabra MOTDocument21 pages6 AlishaChhabra MOTAlisha ChhabraNo ratings yet

- Strategic Mobilization The KeDocument16 pagesStrategic Mobilization The KeDel TokNo ratings yet

- Om 0009Document10 pagesOm 0009prisha4No ratings yet

- 2023 Macroeconomics Final Test SampleDocument2 pages2023 Macroeconomics Final Test Samplek. nastyasNo ratings yet

- "E20" Surface Mount Productivity Improvement Project - Phase 1Document51 pages"E20" Surface Mount Productivity Improvement Project - Phase 1JAYANT SINGHNo ratings yet

- 30 Pantry Organization Ideas and Tricks - How To Organize A PantryDocument1 page30 Pantry Organization Ideas and Tricks - How To Organize A PantryCKNo ratings yet

- Formate of Business LetterDocument14 pagesFormate of Business LetterMuhammad Hamdan AfridiNo ratings yet

- Deed of Absolute Sale Bod OnDocument4 pagesDeed of Absolute Sale Bod OnNeil John FelicianoNo ratings yet

- CH 05Document37 pagesCH 05Janna KarapetyanNo ratings yet

- 13 - Project Procurement Management-Online v1Document41 pages13 - Project Procurement Management-Online v1Afrina M.Kom.No ratings yet

- Swarovski Proper Use GuidelinesDocument14 pagesSwarovski Proper Use Guidelinesasmiaty83No ratings yet

- Set8 Maths Classviii PDFDocument6 pagesSet8 Maths Classviii PDFLubna KaziNo ratings yet

- Market Segmentation Strategic Analysis and Positioning ToolDocument4 pagesMarket Segmentation Strategic Analysis and Positioning ToolshadrickNo ratings yet

- 43-Assignment-Business Studies Class Xii WorksheetsDocument81 pages43-Assignment-Business Studies Class Xii WorksheetsvinayakkanchalNo ratings yet

- CPAR 92 AUD-1st PB SolDocument3 pagesCPAR 92 AUD-1st PB SolEmmanuel TeoNo ratings yet

- The Rise of NFT FundraisingDocument36 pagesThe Rise of NFT FundraisingTrader CatNo ratings yet

- MCom - Accounts ch-13 Topic3Document19 pagesMCom - Accounts ch-13 Topic3Sameer GoyalNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship: It Is A Strategic Process of Innovation & New Venture CreationDocument23 pagesEntrepreneurship: It Is A Strategic Process of Innovation & New Venture CreationsalsabilNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Framework of IWBDocument21 pagesAn Integrative Framework of IWBpongthepNo ratings yet

- ACT 141-Module 1-Assurance ServicesDocument98 pagesACT 141-Module 1-Assurance ServicesJade Angelie FloresNo ratings yet

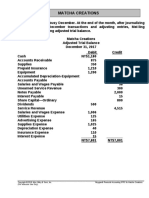

- MC4 Matcha Creations: (For Instructor Use Only)Document2 pagesMC4 Matcha Creations: (For Instructor Use Only)Reza eka PutraNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Habitual Entrepreneurs in Wales Awab Dali 09.09.2016 03.03.2020Document65 pagesCharacteristics of Habitual Entrepreneurs in Wales Awab Dali 09.09.2016 03.03.2020Awab DaliNo ratings yet

- STATICVendor Document Submission Checklist 12 Feb 2015Document9 pagesSTATICVendor Document Submission Checklist 12 Feb 2015zhangjieNo ratings yet

- AshZjxFuEemP8Qpm209XvA Rewiring-Trade-FinanceDocument5 pagesAshZjxFuEemP8Qpm209XvA Rewiring-Trade-Financezvishavane zvishNo ratings yet

- Thesis 2016-Anthony Amoah CORRECTED PDFDocument209 pagesThesis 2016-Anthony Amoah CORRECTED PDFWalamanNo ratings yet

- SM SX 52 SpecificatonDocument2 pagesSM SX 52 SpecificatonAli HussnainNo ratings yet

- MAXIMUM Master Socket Set, 300-Pc, CRV, Nickel-ChDocument1 pageMAXIMUM Master Socket Set, 300-Pc, CRV, Nickel-Chbhattikulvir027No ratings yet