Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Answer To The Question No. 3 (A)

Uploaded by

RimiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Answer To The Question No. 3 (A)

Uploaded by

RimiCopyright:

Available Formats

Answer to the Question no.

3(a)

A buy-in in the financial markets is an occurrence in which an investor is

forced to repurchase shares of security because the seller of the original

shares did not deliver the securities in a timely fashion or did not deliver

them at all.

A buy-in can also be a reference to a person or entity buying shares or a

stake in a company or other holding. In psychological terms, the buy-in is

the process of someone getting on board with an idea or concept that is

not their own but nonetheless appeals to them.

A buy-in is a reference to the repurchasing of shares by an investor

because the original seller failed to deliver the shares as promised. A buy-in

can also be an agreement to purchase shares of something, in some cases

to buy a stake in a company that also has other owners.

Since most owners are generally interested in acquiring only a specific type

of constructed facility, they should be aware of the common industrial

practices for the type of construction pertinent to them. Likewise,

the construction industry is a conglomeration of quite diverse segments and

products. Some owners may procure a constructed facility only once in a

long while and tend to look for short term advantages. However, many

owners require periodic acquisition of new facilities and/or rehabilitation of

existing facilities. It is to their advantage to keep the construction industry

healthy and productive. Collectively, the owners have more power to

influence the construction industry than they realize because, by their

individual actions, they can provide incentives or disincentives for

innovation, efficiency and quality in construction. It is to the interest of all

parties that the owners take an active interest in the construction and

exercise beneficial influence on the performance of the industry.

In planning for various types of construction, the methods of procuring

professional services, awarding construction contracts, and financing the

constructed facility can be quite different. For the purpose of discussion,

the broad spectrum of constructed facilities may be classified into four

major categories, each with its own characteristics.

Residential housing construction includes single-family houses, multi-family

dwellings, and high-rise apartments. During the development and

construction of such projects, the developers or sponsors who are familiar

with the construction industry usually serve as surrogate owners and take

charge, making necessary contractual agreements for design and

construction, and arranging the financing and sale of the completed

structures. Residential housing designs are usually performed by architects

and engineers, and the construction executed by builders who hire

subcontractors for the structural, mechanical, electrical and other specialty

work. An exception to this pattern is for single-family houses which may be

designed by the builders as well.

The residential housing market is heavily affected by general economic

conditions, tax laws, and the monetary and fiscal policies of the

government. Often, a slight increase in total demand will cause a

substantial investment in construction, since many housing projects can be

started at different locations by different individuals and developers at the

same time. Because of the relative ease of entry, at least at the lower end of

the market, many new builders are attracted to the residential housing

construction. Hence, this market is highly competitive, with potentially high

risks as well as high rewards.

Institutional and commercial building construction encompasses a great

variety of project types and sizes, such as schools and universities, medical

clinics and hospitals, recreational facilities and sports stadiums, retail chain

stores and large shopping centers, warehouses and light manufacturing

plants, and skyscrapers for offices and hotels. The owners of such buildings

may or may not be familiar with construction industry practices, but they

usually are able to select competent professional consultants and arrange

the financing of the constructed facilities themselves. Specialty architects

and engineers are often engaged for designing a specific type of building,

while the builders or general contractors undertaking such projects may

also be specialized in only that type of building.

Because of the higher costs and greater sophistication of institutional and

commercial buildings in comparison with residential housing, this market

segment is shared by fewer competitors. Since the construction of some of

these buildings is a long process which once started will take some time to

proceed until completion, the demand is less sensitive to general economic

conditions than that for speculative housing. Consequently, the owners may

confront an oligopoly of general contractors who compete in the same

market. In an oligopoly situation, only a limited number of competitors

exist, and a firm's price for services may be based in part on its competitive

strategies in the local market.

Specialized industrial construction usually involves very large scale projects

with a high degree of technological complexity, such as oil refineries, steel

mills, chemical processing plants and coal-fired or nuclear power plants.

The owners usually are deeply involved in the development of a project,

and prefer to work with designers-builders such that the total time for the

completion of the project can be shortened. They also want to pick a team

of designers and builders with whom the owner has developed good

working relations over the years.

Although the initiation of such projects is also affected by the state of the

economy, long range demand forecasting is the most important factor

since such projects are capital intensive and require considerable amount of

planning and construction time. Governmental regulation such as the

rulings of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Nuclear Regulatory

Commission in the United States can also profoundly influence decisions on

these projects.

Infrastructure and heavy construction include projects such as highways,

mass transit systems, tunnels, bridges, pipelines, drainage systems and

sewage treatment plants. Most of these projects are publicly owned and

therefore financed either through bonds or taxes. This category of

construction is characterized by a high degree of mechanization, which has

gradually replaced some labor-intensive operations.

The engineers and builders engaged in infrastructure construction are

usually highly specialized since each segment of the market requires

different types of skills. However, demands for different segments of

infrastructure and heavy construction may shift with saturation in some

segments. For example, as the available highway construction projects are

declining, some heavy construction contractors quickly move their work

force and equipment into the field of mining where jobs are available.

Answer to the Question no. 3(b)

While there are many ways to address the innumerable performance

metrics of any project, the critical factors always seem to come down to

time and money.

Will the project be delivered on time? Will it be completed within

budgetary constraints and expectations? Stay on top of these essential

parameters in your project management dashboards.

Timing

Every business has to deliver product or services in a timely way. Windows

of business opportunities close quickly, market trends change, and holidays

come and go. The following strategies help to effectively monitor and

manage project timing:

Incorporate enough detail. Show enough grain in your project schedule to

allow you to assess the progress of the project and whether or not work is

being accomplished in the time frame allotted to it. Include a bit of project

history from the previous weeks or months along with the list of work to be

accomplished and the team members assigned to various project

components. Be sure to list the actual time spent on tasks compared to the

time allocated to them. This data will help determine whether the current

schedule should be adjusted one way or the other to successfully meet

delivery dates.

Create milestones. Break down the entire project into manageable

milestones. Then you’ll be able to compare three trend lines: the timeline

originally targeted, the amount of time already invested towards

completion, and the actual percentage of completion that the project is

currently reflecting. These variables will give you a clear idea of how the

project is performing and enough perspective to forecast more effectively.

Use a time-honored tool. Earned Value Analysis (EVA) charts are valuable

tools to help you measure your project’s progress at any given point in

time, as well as forecast its completion date and cost. You’ll readily see

when a project needs a course-correction so adjustments can be made to

keep it on track for on time delivery.

Money

The other side of the fulfillment coin is money. Keeping the project within

budget is essential to its (and your) success. Key strategies to stay on top of

your project’s budget include:

Know where you stand: Use a Project Snapshot Report to view your

project’s budget compared to what’s been billed and what has not yet been

billed to your client. This way you’ll know the status of your budget at any

stage of its timeline.

Include Timesheet Details: Pair the Snapshot Report with a Timesheet

Details Report to provide even more insight. Make sure you can easily

separate time by project, phase, and employee so you can easily identify

and resolve any problems. From this, you’ll add an additional layer of depth

to your dashboard.

There are two main control variables available to the Project Manager

during the course of a project: hours and progress. These two variables

enable us to apply Earned Value Management principles and thus gain

insight into project performance at any time.

The “hours” variable is used to build a connection between project time

and costs, both in terms of estimates and real values. Time and cost move

together; “time is money”. Using “hours”, a Project Manager plans his or

her entire project and calculates the time needed to complete it, as well as

the resulting costs.

We should be clear that more work time does not equal more progress

in a project, and a good Project Manager should be fully aware of certain

concepts regarding types of hours:

Budgeted hours: this represents the number of hours available for

completing the project. This will lead to certain costs that the

Project Manager can stipulate.

Estimated hours: once the project is defined on a task level (with

a schedule and time estimates, as well as a selection of resources

involved), hours can then be assigned to users. An estimate will be

made of the number of hours needed by each user to complete the

task; in other words, the number of hours considered appropriate to

complete the activity. Each user will have a cost per hour assigned to

their professional category so that their assigned effort will be

reflected in an estimated cost.

Real hours: the number of hours effectively worked can be obtained

at any point during the course of the project and reported by the

project team members. Based on their individual cost, the real cost of

the resources at any time can also be obtained.

Accepted hours: the hours reported by users can be accepted or

corrected manually by the Project Manager. It may therefore be the

case that the real cost does not fully depend on the reported hours

but also on whether they are accepted by the Project Manager.

The Earned Value Method (EVM) is used to measure progress on project

completion in an objective fashion. This combines three vitally important

aspects in the completion of a project: technical (compliance with the

planned work); costs (whether more or less is spent than originally

planned); and deadline (whether the project is ahead or behind schedule).

The components of this are described below:

Earned Value (EV): the progress on activities planned at the start of

the project at any given time is determined. This gives rise to another

series of data that is referred to as Earned Value (EV), indicating the

progress made to date.

Planned Value (PV): the detailed planning of the project indicates

what is going to be done and on what dates, as well as how much it

was thought it will cost (both in personal and material effort). These

values are known as the Planned Value, which is nothing more than a

budget spread. The total Planned Value is usually called the Budget at

Completion (BAC).

Actual Cost (AC): the cost incurred by the work carried out on a task

during a period. This reflects the total cost to date in relation to the

work completed. For a project to fall within estimated parameters, it

would need to correspond to what was budgeted for the PV and

measured by the EV.

Analysis of Earned Value

Cost Variance (CV): CV = EV-AC

Schedule Variance (SV): SV = EV-PV

Cost Performance Index (CPI): CPI = EV/AC

Schedule Performance Index (SPI): SPI = EV/PV

As Project Manager, you should follow the advice of Benjamin Franklin in

the 18th Century and “remember that time is money”. Do not forget to

apply the best practices in Earned Value Management and thus monitor the

status of your projects relatively easily and simply, being this the perfect

time as well to get a good tool of project management, that allowed us to

make our work easier.

You might also like

- Strategy Toolkit - Frameworks, Tools & Templates by Ex-McKinseyDocument1 pageStrategy Toolkit - Frameworks, Tools & Templates by Ex-McKinseyLAMIA AL ZAYER0% (3)

- Project Management For ConstructionDocument285 pagesProject Management For Constructionrasputin078080349495% (21)

- Contract Management 1Document12 pagesContract Management 1Sharman Mohd ShariffNo ratings yet

- Movies and Mass CultureDocument22 pagesMovies and Mass CultureSnailsnailsNo ratings yet

- Sample of 3000 WordsDocument24 pagesSample of 3000 WordsENGLISH SQUAD UPNo ratings yet

- Project Management For ConstructionDocument138 pagesProject Management For ConstructionMirasol Coliao SalubreNo ratings yet

- Construction Project ManagementDocument286 pagesConstruction Project ManagementwilsonsulcaNo ratings yet

- PPCMDocument460 pagesPPCMPradeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Project Management For Construction and Civil Engg.Document487 pagesProject Management For Construction and Civil Engg.TauseefNo ratings yet

- Owners RequirementsDocument27 pagesOwners RequirementsOkokon BasseyNo ratings yet

- Life Cycle Phases Construction ProjectsDocument10 pagesLife Cycle Phases Construction Projectsaymanmomani2111No ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument8 pagesChapter Onexuseen maxamedNo ratings yet

- Construction Project Life Cycle PhasesDocument10 pagesConstruction Project Life Cycle Phasesaymanmomani2111100% (1)

- Construction - The Owner's PerspectiveDocument19 pagesConstruction - The Owner's PerspectiveGeorgeNo ratings yet

- Owners' Perspective on Project ManagementDocument22 pagesOwners' Perspective on Project ManagementDeyb TV GamingNo ratings yet

- Project Management for Construction: Understanding the Owners' PerspectiveDocument21 pagesProject Management for Construction: Understanding the Owners' PerspectivePrem Kumar DharmarajNo ratings yet

- Project Management For Construction, Chris HendricksonDocument485 pagesProject Management For Construction, Chris HendricksonDaryl BadajosNo ratings yet

- Const. Mgmt. Chp. 01 - The Owners' PerspectiveDocument27 pagesConst. Mgmt. Chp. 01 - The Owners' PerspectiveFaiz AhmadNo ratings yet

- Record, Nov. 19, 2001) - of This Total, About $214 Billion Is Estimated For Residential Projects, $167 Billion ForDocument3 pagesRecord, Nov. 19, 2001) - of This Total, About $214 Billion Is Estimated For Residential Projects, $167 Billion ForJOSENo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - CPM - Owners PerspectiveDocument19 pagesUnit 1 - CPM - Owners PerspectiveRTNo ratings yet

- BASAK-G-Tuning Into Your ClientDocument6 pagesBASAK-G-Tuning Into Your ClientegglestonaNo ratings yet

- Construction Project ManagementDocument4 pagesConstruction Project ManagementMariel Dalisay PalmonesNo ratings yet

- Yangon Technological University Department of Civil EngineeringDocument28 pagesYangon Technological University Department of Civil Engineeringthan zawNo ratings yet

- Constract, Specification and Quantity SurveyingDocument72 pagesConstract, Specification and Quantity SurveyingDejene TsegayeNo ratings yet

- Producing a Tender Table of ContentsDocument38 pagesProducing a Tender Table of ContentsMohamed Gheita50% (2)

- CPM PDFDocument114 pagesCPM PDFJithesh.k.sNo ratings yet

- Project Management For Construction - The Owners' PerspectiveDocument18 pagesProject Management For Construction - The Owners' Perspectivemaaz hussainNo ratings yet

- 1.owner's PerpectiveDocument13 pages1.owner's PerpectiveLyka TanNo ratings yet

- Estimation and Costing PDFDocument112 pagesEstimation and Costing PDFØwięs MØhãmmed100% (1)

- Nue LarkDocument11 pagesNue LarkOlayemi ObembeNo ratings yet

- Guideline For Control & Automation Project ManagementDocument10 pagesGuideline For Control & Automation Project ManagementTirthankar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Construction Project Review Questions & ExercisesDocument7 pagesConstruction Project Review Questions & ExerciseslarraNo ratings yet

- TPUT Cavite Construction Cost Estimation ReportDocument22 pagesTPUT Cavite Construction Cost Estimation ReportPercival ArcherNo ratings yet

- Project management in 5 stagesDocument9 pagesProject management in 5 stagesanuj jainNo ratings yet

- Building ConstructionDocument7 pagesBuilding ConstructionRaheel AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Owner Report FileDocument16 pagesThe Owner Report FileENGLISH SQUAD UPNo ratings yet

- 1Document17 pages1Adane AbebeNo ratings yet

- How You Can Respond To Challnges During Construction ProjectsDocument11 pagesHow You Can Respond To Challnges During Construction ProjectsOlayemi ObembeNo ratings yet

- Chapter01-The Owner's PerspectiveDocument19 pagesChapter01-The Owner's PerspectiveaboNo ratings yet

- Busitema University Construction Management AssignmentDocument9 pagesBusitema University Construction Management AssignmentJoshua S4j Oryem OpidoNo ratings yet

- Sourav Sasmal ProjectDocument10 pagesSourav Sasmal ProjectSourav SasmalNo ratings yet

- Unit 2Document18 pagesUnit 2321126508L06 PydiakashNo ratings yet

- Project Development Evaluation and FeasibilityDocument17 pagesProject Development Evaluation and FeasibilityHamza ZainNo ratings yet

- Estimation and CostingDocument112 pagesEstimation and Costingjs kalyana rama83% (12)

- Bijoy AV - Successful Procurement of ConstructionDocument11 pagesBijoy AV - Successful Procurement of ConstructionBijoy AVNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document7 pagesChapter 3Eduardo OrozNo ratings yet

- CPM Take Home ExamDocument7 pagesCPM Take Home ExamMichael Angel PascualNo ratings yet

- Unit - 1 Assignment: Submitted By: Neha NarwalDocument5 pagesUnit - 1 Assignment: Submitted By: Neha NarwalVinay SainNo ratings yet

- Project Design and Dev'tDocument38 pagesProject Design and Dev'tasratNo ratings yet

- Rich Text Editor File: Construction TypesDocument6 pagesRich Text Editor File: Construction TypesMuhannad AbdulRaoufNo ratings yet

- Constructing ExcellenceDocument5 pagesConstructing ExcellenceKrishna KumarNo ratings yet

- Construction Project Life CycleDocument7 pagesConstruction Project Life Cycleልደቱ ገብረየስNo ratings yet

- PM Assignment 1 SolvedDocument7 pagesPM Assignment 1 SolvedRahul GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Parties of A Construction ProjectDocument8 pagesParties of A Construction ProjectT N Roland BourgeNo ratings yet

- Electricity EconomicsDocument5 pagesElectricity Economicskennyajao08No ratings yet

- Construction: Donn E. HancherDocument4 pagesConstruction: Donn E. Hancherantoni999No ratings yet

- Capital Projects and ConstructionDocument0 pagesCapital Projects and ConstructionbillpaparounisNo ratings yet

- Interview On Construction Company: How To Cope With The PandemicDocument7 pagesInterview On Construction Company: How To Cope With The PandemicNicole Osuna Dichoso100% (1)

- Cve511 Civil EngineeringDocument9 pagesCve511 Civil EngineeringMoses KufreNo ratings yet

- Integrated Project Planning and Construction Based on ResultsFrom EverandIntegrated Project Planning and Construction Based on ResultsNo ratings yet

- Migration of Network Infrastructure: Project Management ExperienceFrom EverandMigration of Network Infrastructure: Project Management ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Impact of Crude Oil On Indian Economy: November 2015Document17 pagesImpact of Crude Oil On Indian Economy: November 2015Rohan SharmaNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps in Compost ProductionDocument28 pages10 Steps in Compost ProductionJerico MirandaNo ratings yet

- Problem 3-1 Problem 3-1Document26 pagesProblem 3-1 Problem 3-1MichelleNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management: Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument3 pagesInventory Management: Multiple Choice QuestionsHazel Jane Esclamada33% (3)

- Financial Statement Analyses of Tata Motors LimitedDocument12 pagesFinancial Statement Analyses of Tata Motors LimitedJADUNATH HEMBRAMNo ratings yet

- Calendar 12Document20 pagesCalendar 12Hotel EkasNo ratings yet

- Global Supply Chain Management: The Fresh Connection Simulation ReportDocument5 pagesGlobal Supply Chain Management: The Fresh Connection Simulation ReportnishantNo ratings yet

- Westech Industrial Ltd. and Plug Power Inc. Form A Strategic Partnership To Accelerate Hydrogen Fuel Cell Adoption As An Alternative Energy Source in Western CanadaDocument3 pagesWestech Industrial Ltd. and Plug Power Inc. Form A Strategic Partnership To Accelerate Hydrogen Fuel Cell Adoption As An Alternative Energy Source in Western CanadaPR.comNo ratings yet

- AfmechDocument5 pagesAfmechfelixboridas23No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Indian Economy. (1950-1990)Document27 pagesChapter 2 - Indian Economy. (1950-1990)somyaasingh262005No ratings yet

- Book 6051aa0a8d6aeDocument18 pagesBook 6051aa0a8d6aeadeptyadav1No ratings yet

- Asia's longest high-speed test track NATRAX inaugurated in IndoreDocument85 pagesAsia's longest high-speed test track NATRAX inaugurated in Indorebikram111209005No ratings yet

- Loyalitas PasienDocument6 pagesLoyalitas PasienAnzzis Alfian PrabowoNo ratings yet

- Gino Evan Dal Pont - CCH Australia Limited, - Law of Limitation (2016, LexisNexis Butterworths) - Libgen - LiDocument1,105 pagesGino Evan Dal Pont - CCH Australia Limited, - Law of Limitation (2016, LexisNexis Butterworths) - Libgen - LiLinming HoNo ratings yet

- Review On Coffee Production and Marketing in EthiopiaDocument9 pagesReview On Coffee Production and Marketing in Ethiopiayusuf mohammedNo ratings yet

- DLF Corporate ParkDocument2 pagesDLF Corporate ParkSid KharbandaNo ratings yet

- GMW15195 - Aug2019 - Documentation For Control of Appearance Aesthetic Quality - Colour & GlossDocument5 pagesGMW15195 - Aug2019 - Documentation For Control of Appearance Aesthetic Quality - Colour & GlosslauraNo ratings yet

- INVENTORY OF SAN SIMON PRODUCTSDocument20 pagesINVENTORY OF SAN SIMON PRODUCTSJockxehiny Lucia Lara MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- UltraTech Cement vs Ambuja Cement: Key Facts and ComparisonDocument5 pagesUltraTech Cement vs Ambuja Cement: Key Facts and ComparisonBishal NahataNo ratings yet

- Buy Entry Intraday, Technical Analysis ScannerDocument2 pagesBuy Entry Intraday, Technical Analysis ScannerVipul SolankiNo ratings yet

- Histroy of PineappleDocument2 pagesHistroy of PineappleNorsakinah Mohd AhmadNo ratings yet

- HARIDRA'SDocument59 pagesHARIDRA'SAdigithe ThanthaNo ratings yet

- Alpha Farms Company Limited (Afc) PresentationDocument24 pagesAlpha Farms Company Limited (Afc) PresentationDerick JayNo ratings yet

- Anurag Bhatia's ResumeDocument1 pageAnurag Bhatia's ResumeAnurag BhatiaNo ratings yet

- El Gran Gringo Selecciones de CaféDocument2 pagesEl Gran Gringo Selecciones de CaféandreshostiaNo ratings yet

- ProtectionismDocument2 pagesProtectionismdafer krishiNo ratings yet

- Corporate Vision: Back To TopDocument73 pagesCorporate Vision: Back To TopUsman KhanNo ratings yet

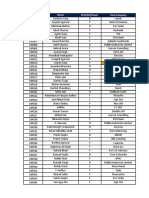

- Roll No. Name PPO/PPI/Finals Final CompanyDocument48 pagesRoll No. Name PPO/PPI/Finals Final CompanyYash AgarwalNo ratings yet