Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sexual Economies of War and Sexual Technologies of

Uploaded by

Melvin MathewOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sexual Economies of War and Sexual Technologies of

Uploaded by

Melvin MathewCopyright:

Available Formats

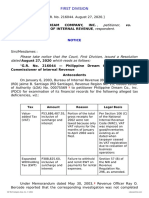

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/315769524

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body: Militarised

Muslim masculinity and the Islamist production of concubines for the

caliphate

Article in Agenda · December 2016

DOI: 10.1080/10130950.2016.1275558

CITATIONS READS

3 119

1 author:

Fatima Seedat

University of Cape Town

11 PUBLICATIONS 73 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Agenda: Special Volume on Women, Religion and Security View project

Sexuality and Peace Studies View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Fatima Seedat on 03 November 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Agenda

Empowering women for gender equity

ISSN: 1013-0950 (Print) 2158-978X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ragn20

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies

of the body: Militarised Muslim masculinity and

the Islamist production of concubines for the

caliphate

Fatima Seedat

To cite this article: Fatima Seedat (2016) Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of

the body: Militarised Muslim masculinity and the Islamist production of concubines for the caliphate,

Agenda, 30:3, 25-38

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2016.1275558

Published online: 23 Jan 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 40

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ragn20

Download by: [154.69.132.192] Date: 20 March 2017, At: 12:30

article

Sexual economies of war and sexual

technologies of the body: Militarised

Muslim masculinity and the Islamist

production of concubines for the caliphate

Fatima Seedat

abstract

This article analyses sexuality and subjugation in the context of Islamist militarism. It examines how the Islamic

State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Boko Haram style themselves upon narratives of Islamist militancy that

appear to be historically authentic narratives of Muslim militarism read out of classical legal texts. The article

argues instead that because ISIS and Boko Haram read these narratives through contemporary understandings

of militarism using contemporary sexual technologies of the body, they also read these narratives in entirely

contemporary and modern ways. The product of this reading is therefore also a contemporary form of Islamist

militarism, using contemporary sexual technologies of the body. The justifications for these modern

enactments of militarism, law and sexual subjugation are not to be found in the historical texts, but in the

modern readings of the text. To illustrate these modern readings of sexuality and subjugation, I take up three

publications produced by ISIS, and further, two online fatwas (legal opinions). Viewed against their historical

precedents, the first reveal the aberrant nature of ISIS and Boko Haram style sexual subjugation in terms of

historical legal practice. The online fatwas reveal how ordinary Muslims have come to conceptualise the

intersections of war and sex in ways contrary to the practices of ISIS and Boko Haram.

keywords

sex slavery, Islamic law, consent, ISIS, Boko Haram, militarism

Overview new Muslim masculinities which are mili-

This article analyses the intersections of reli- tarised, hyper-sexualised and articulated as

gion, militarism and sexuality in three resistance to imperialism. Finally the article

aspects.1 The first examines the intersections highlights the ways in which this hyper-sex-

of militarism and sexuality in ISIS enactments ualised and militarised Islamist masculinity

of war to dispel the suggestion that these are is also premised upon a paradigm of sexual

aberrant in the sense that they deviate from control that is essential to historical Muslim

normative practice in the sexual economy of legal narratives of sexuality in marriage and

modern forms of war. The second aspect concubinage, but out of step with contempor-

argues that ISIS uses historical practices in ary Muslim sexual norms. Marriage outside of

distinctly contemporary ways to produce Muslim militarist discourses in a normative

Agenda 109/30.3 2016

ISSN 1013-0950 print/ISSN 2158-978X online

© 2017 Fatima Seedat

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2016.1275558 pp. 25–38

Muslim context at present includes some

article

example of this sexual economy in oper-

aspects of this paradigm of control but it ation. Estimates range from 20 000 to

also includes a second paradigm based on 400 000 women captured to supply the

ideas of consent and mutuality. The result is sexual economy of military personnel in

that Islamist militancy produces a militarised the Japanese imperial endeavour (Sun,

masculinity premised on extreme forms of 2014). Also during World War II, “the Wehr-

sexual control that run contrary to how ordin- macht was running over 500 so-called

ary Muslims conceptualise both sexual “Wehrmachtsbordellen”; German military

relations and resistance to imperialism.2 To brothels which took two forms, garrison

illustrate these second and third aspects, I brothels and field brothels, which gathered

take up three documents on sex enslavement women from concentration camps, work

produced by ISIS and two online fatwas pro- camps, prisoners of war or prostitutes from

duced on two mainstream Muslim fatwa sites. Germany and occupied territories to

provide sexual incentives to military person-

Islamist militancy produces a militarised nel. The total estimate is of 30 000 women

masculinity premised on extreme forms of forced into sex slavery in Nazi occupied

Eastern Europe (Milano, n.d.). Concentration

sexual control

camp brothels are a more recently

researched phenomenon that documents

approximately 200 women recruited as

The sexual economy of war incentives for prison inmates (Herzog,

2008; Sommer, 2009). Women were

However problematic, sex has functioned as screened for sexually transmitted diseases,

a normative element of the economy of war forcibly sterilised and those who became

and therefore ISIS and Boko Haram enact- pregnant were forced to terminate. The

ments of sex in the economy of war are not code word for British brothels established

aberrant to the practice of war. The use of by secret edict for the exclusive use of

sexual labour by ISIS and Boko Haram is British officers, was “blue lamp”, and

portrayed by media and other sources in formed part of British strategy in the First

terms that suggest an aberration caused by World War. The distinction of these brothels

the unique presence of Islam in the ideology from others was to avoid military personnel

of these militarised groups. Yet, the intersec- “sullying their uniform by consorting with

tions of war and sex are not unusual; rather, prostitutes in public” (Makepeace,

they are normative to the sexual economy of 2013:413). In this way British Expeditionary

war by which I refer to the demand and Forces prescribed and enforced “ideal pat-

supply of sex in the context of war. terns of male sexual conduct in war” (Make-

Whereas the use of sex as a weapon of war peace, 2013:413). Recognising the “needs of

has been sufficiently recognised to prompt men” as officers they “were granted excep-

a United Nations Security Council resol- tional permission for visiting” blue lamps.

ution, number 1820, unanimously adopted They were also issued road passes for trans-

in 2008, recognising and condemning the porting prostitutes and married men were

use of rape as a weapon of war and a given special authorisations for brothel

threat to international security,3 the use of visits, prostitutes being considered a

sex in the economy of war is less obvious. natural alternative to an absent wife (Make-

War requires combatants receive a steady peace, 2013:415–8). In Paris, both US and

supply of arms, food and sex; all three are French military officials agreed that sex

considered crucial to the combatants’ was necessary to the war effort, and in the

ability to fight and a number of wars in the view of the US military, control of the body

last century illustrate this. As below, what of the American GI “gave them dominion

distinguishes each instance is the nature of of the French woman’s body as well”

sexual trade or sexual subjugation in each. (Roberts, 2013:162), accordingly, they

The ianfu, Japanese for the euphemism managed the health and mobility of the

applied to women forced into sex to women traded into brothels “run directly

provide ‘comfort’ for soldiers in Indonesia, by and for U.S. soldiers” (Roberts,

Thailand, Burma, Vietnam and other areas 2013:160). Similar efforts were made for US

conquered by Japanese forces in the soldiers in Italy. A study of the sexual

second world war is the most popular economy of war demonstrates how

26 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

the U.S. Army first attempted to gain

article

also that the outcomes of that supply be

control of almost all aspects of soldiers’ managed, in battle and back at the comba-

sexuality and then tried to carefully tant’s home. Sexually transmitted diseases

manage and regulate that sexual and pregnancies are two material outcomes

economy to best fulfill the army’s mis- of the sexual economy of war. Infidelity to

sions … It encouraged those aspects of partners at home and the violation of peace

sexual identity that the army believed time sexual norms are other outcomes.

benefited the service – for instance, hyper- Women forced into military prostitution

masculine demeanor and actions (Byers, were sterilised or forced to abort, subject to

2012:403). medical scrutiny of their bodies, and preven-

tative or curative treatments were enforced

More recently, Guatemalan indigenous com- by the military (Makepeace, 2013). In these

munities have sued the state for the sexual ways military strategy includes the manage-

slavery of Mayan Q’eqchi women. Closer to ment of sexual reproduction and sexually

home, in African National Congress (ANC) transmitted diseases amongst combatants

women’s accounts of Quatro, a training to maintain the healthy supply of comba-

camp for the ANC, and Swapo women’s tants and sustain the momentum of war

experiences in Lubongo, they recount the (Makepeace, 2013).

regular rape of female cadres, in the camp

to support the struggle for liberation from the intersections of war and sex are not

apartheid rule but required also to have sex unusual, even if they are brutal

with their senior commanders and others

(Trewhela, 1993a:1993b).

The examples above illustrate that the

Along these lines, in Baghdadi’s cali-

intersections of war and sex are not

phate, Yazidi women have been used to

unusual, even if they are brutal. Yet in

supply the sexual needs of a militarised

media and other representations of this

force constituted from a disparate group of

intersection in the war efforts of Islamist

expatriate and local fighters. In Nigeria,

militants, there is a suggestion that the inter-

girls and young women from Chibok and

sections of sex and war are unusual, almost

surrounding areas have been forcibly taken

aberrational. Because the combatants are

to supply the sexual economy of the Boko

Muslim their practices are portrayed as

Haram fighters. I explore these last two

anomalous to the economy of war, and the

below but locate them here to include

suggestion is that the anomaly may be

these practices amongst the various ways

traced to the distance between European or

in which the management of war includes

western and Muslim norms. In response to

the management of sex as a wartime com-

the othering of Muslim practices which are

modity. Accordingly, one American

ascribed to the distance between the West

General, George Patton said of his troops:

and its Muslim other, Armando Salvatore

“if they don’t fuck, they don’t fight” (Moon,

(2016:73) argues instead for

2015:143), making a definitive link between

the prosecution of the war effort and the

the historic closeness and density of the

sexual activity of the combatant conceived

West’s interactions and competition with

in heteronormative terms as a married or

the Islamic ecumene and its political

unmarried straight male (and exclusive of

centers, more than any purported cultural

similarly single or married queer men and

distance and civilizational alterity.

straight or queer women). Patton’s state-

ment formulates the combatants’ sexuality

The multiple imbrications of modernity as

at the intersections of penetration and mili-

well as western military forces present in

tarism, producing a militarised hyper-

the caliphate suggest that this distance

masculinity that necessitates the supply

may be even smaller than we imagine. For,

and availability of sex for combatants; and

historically too, the distance was not great,

the violent nature of war means that this

sexual concubinage practices are evident in

sex may be either solicited formally or

a number of related near eastern contexts.

enforced violently.

Ancient practices that illustrate the place of

In addition to the supply of sex to comba- sex in war are represented in Deuteronomy,

tants, the economy of sex in war requires the fifth book of the Pentateuch, 21:10–14,

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body 27

where female captives are considered Therefore, rather than a simple re-enact-

article

amongst the spoils of war, which practice ment of historical Muslim practice in the

recent scholarship describes as genocidal present, ISIS and Boko Haram succeed in

rape intent on erasing the ethnic identity of producing forms of war time sexuality that

the captive women (Rey, 2016). Genesis: are contemporary to present day sexual

25:1–5 and 1 Chronicles1:32 also refer to technologies of the body, namely the ways

Abraham’s marriage to the pilegesh, in which women’s bodies are disciplined to

Hebrew for concubine. And at present the manage and meet the needs of a militarised

distance between the historical and contem- masculinity (Armstrong, n.d.).4 Through the

porary caliphate appears even smaller; it is apparent re-enactment of the historical in

as though in the production of concubines the present times, what I refer to as an

is the completion of the contemporary attempt to make the ‘historical present’,

caliphate. they produce a contemporary narrative of

Islam which is centred on the intersections

Much like the sexual economy of other of militarism and sexuality, mediated

wars, ISIS and Boko Haram, more so the through notions of Muslim piety. What is

former, have made women’s sexual and the origin of this narrative which centres on

reproductive labour a matter of open trade the hypersexual and militarised Muslim mili-

as vital to the health of combatants and the tant in control of the sexual other through

momentum of war as the supply of the institution of forms of female sex

weapons and food. Less than an aberration, slavery justified as a practice of war? Are

however unacceptable and egregious, these they simply re-enacting the past or are they

practices are consonant with historical and producing contemporary forms of militarism

contemporary war time strategies for mana- and sexuality?

ging the sexual economy of war. And there-

fore, as significant an argument as the

brutality of the forms of sex trade ISIS and Muslim political memory and the

Boko Haram conduct is the brutality of the

sexual economy of war and military

operations of sex slavery through

combat. In the sexual economy of war the sexual technologies of the body

patriarchy of imperialism and the impulse I argue first that the discourse of Islamist mili-

to control territory is intimately linked with tarism such as that of ISIS and Boko Haram

the patriarchal impulse to control women’s produces a modern Muslim militarised mas-

bodies, connecting the sexually penetrating culinity through a ‘historical present’ that

male body with the conquering military revives the figure of the jariya or female

male body. While slavery as an economic slave. Fatima Mernissi (1996) has argued

institution has been compatible with Islam that the jariya is central to the political

as an historical system of law and econ- memory of the historical Abbasid caliphate.

omics, ISIS has prioritised sexual slavery of For scholars of Muslim women’s history,

women over other historical forms of therefore, it is not surprising that the narrative

slavery; similarly, Boko Haram has priori- of enslaved women has become central to

tised taking women captives over other the narrative of al-Baghdadi’s caliphate

forms of captivity. The Islamist militants’ under ISIS. Mernissi offers a pressing analy-

trade in women as sex slaves represents sis of the treatment of sex difference in

the sexual economy of the caliphate at war. Islamic thought and the location of slavery

Thus the conclusion, that the sexual in Muslim political memory. The first years

economy of ISIS and Boko Haram militarism of Islamic history, she argues, are years

in pursuit of the caliphate is not unique to the where women feature prominently in the pro-

war time practices of Muslims, but may be phetic narrative as disciples who are also

generalised to the sexual economy of advisers, strategists and otherwise active

warfare, including modern wars. traders, politicians and soldiers. The second

period following soon after and terminating

ISIS and Boko Haram succeed in producing in the later Umayyad period, is of aristocratic

wives instrumental in consolidating the for-

forms of war time sexuality that are con-

tunes of the empire and marked by their

temporary to present day sexual technol- “capacity to defy men in a position of auth-

ogies of the body ority”, whether in the refusal either to veil or

28 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

to accept polygyny (Mernissi, 1996:83). The

article

humanity, God is master, whether of the

third period, associated with the Abbasids, present or the hereafter, commander of all

she characterises as the period of the jawari that is good, purveyor of all knowledge. Sim-

(single: jariya), whose figure dominates nar- ultaneously however, God is also benefi-

ratives of women’s marginal status in later cent, all loving and all merciful. Modelled

Islamic political thought. The Abbasid era is on this, the relationship of God with human-

characterised by the often accomplished ity is that of a benevolent master with a

slave women captured in Muslim conquest willing slave. On the legalities of slavery,

across the empire and who begin their lives there is little in a slave’s life that is not legis-

notoriously as slaves but end in prominence lated, since together with age, puberty, sex

as mothers of caliphs. The popular narrative and mental ability, enslavement is a key

of the subjugated feminine, Mernissi argues, determinate of social, legal and spiritual

is best traced to this period, where the status. Legal manuals hold detailed presen-

ensuing “cult of courtesans in ‘political tations of the legal norms proscribing licit

memory’ reflects our nostalgia for absolut- forms of enslavement and guidelines for

ism” (Mernissi, 1996:87). owners and enslaved people on the limits

and terms of enslavement. Amongst these

How predictable, then, to see in the con-

are rules establishing the paternity of the

temporary revival of the caliphate the simul-

child of a concubine whom, it explains,

taneous revival of the jariya, representative

upon giving birth to her master’s child may

of “male fantasies, inspired stories from the

no longer be traded and, upon death of her

days of imperial Islam” (Freamon, 2014); as

master, is also released from captivity

above, it is as though in the production of

(Qudū rı̄, 2010)

Yazidi concubines and Chibok captive

‘wives’ is the militarists’ imaginings of the Islamist militants appear to draw upon

caliphate made complete as it is, simul- two narratives in the context of sex slavery.

taneously, also made both historical and con- The first is the political narrative explained

temporary.5 But before we jump to easy by Mernissi’s argument on the place of the

parallels to argue as Islamist militants do jariya in political memory which combines

that their practices are merely contemporary a memory of the subjugated feminine and

re-enactments of historical caliphal gender nostalgia for territorial absolutism. This is a

relations or that they simply make the ‘histori- mythical narrative of a Muslim past where

cal present’, we should bear in mind the mul- the caliph controlled both his territory and

tiple forms of distance that separate the his women. The second narrative Islamist

historical practice and its contemporary militants appear to draw upon comes from

forms. Not only are these practices anachro- nationalist understandings of masculinity

nistic in that they attempt at the present day shaped in the protection of the nation, its

enactment of historical norms but, as below, women and traditions from colonial others.

the capture of Yazidi women of al-Bhagdadi’s

caliphate and the kidnapping of the Chibok Colonised men were called upon not only to

girls of Boko Haram, also represent contem-

rescue the land from penetration by the

porary aberrations of historical concubinage

practice. The ways in which militarised Isla- outsider, but also to protect Muslim women

mists have enslaved women for sex rep- rendered similarly vulnerable to colonial

resent modern sexual technologies of the violation

body and, from the perspective of the histori-

cal Islamic laws of war, aberrant expressions

The metaphor of the colonial era framed

of the historical sexual economy of war.

Muslim nations as locations of rape and

Together, however, they produce concubines

colonial powers as penetrative rapists

and ‘wives’ for the contemporary caliphate.

(Adibi, 2006). Colonised men were called

The understanding of slavery in Islamic upon not only to rescue the land from pen-

thought rests upon a corpus of refined intel- etration by the outsider, but also to protect

lectual effort that produces everything from Muslim women rendered similarly vulner-

the metaphor of spiritual submission of able to colonial violation (Adibi, 2006).

humanity to God to the very minutiae of These nationalist narratives of masculinity

law governing the enslavement of people. prescribe ways of being male and female

On the relationship between God and which are further shaped by global

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body 29

hegemonic masculinities. When domestic

article

where sex in the economy of war is norma-

masculinity finds itself humiliated and tive. Thus they produce uniquely contem-

forced to save the motherland, sisters, porary forms of Islamist militarism, modern

daughters and wives amongst them, and forms of sexual control, and modern read-

where this is coupled with active resistance ings of Islamic law facilitated by modern

to western imperial and hegemonic masculi- technologies for managing sexual

nities, local Muslim masculinity comes to be reproduction.

subordinated to the hegemonic masculinity

of the invading coloniser. In response, a These modern readings of law and tech-

new militarised Muslim masculinity offers a nologies for managing sexual reproduction

counter claim to produce an alternate mas- are illustrated in a series of three docu-

culinity. My suggestion is that in the sexual ments on slavery produced by ISIS. The

economy of Islamist militarism, the impera- last is a fatwa and it is preceded by an

tives of the caliphate and the nation state earlier question and answer publication

combine; in the operations of religion, war titled ‘Questions and Answers on Captives

and sexuality. Groups such as ISIS and and Slaves’ produced by the ISIS Ministry

Boko Haram produce a masculinity that is of Research and Legal Opinion, in the

located dually in the historical absolutism month of Muharram 1436 (Common Era

that accompanies the political memory of [CE] 25 October-24 November 2014). The

the jariya, of the caliphate, and in the mili- first of the three publications is the ISIS

tarised freedom-fighter or saviour of Islam newsletter Dabiq Issue 4, produced in the

who upholds the sovereignty of the postco- month of Dhul Hijja 1435 (CE 26 September

lonial nation state. While the narratives of -24 October 2014). Presented just a month

Islamist militarism that conflate the caliphate before the legal manual, the newsletter

and the nation state, two widely different Dabiq includes a three page entry, ‘The

political formations, may appear to be con- revival of slavery before the hour’ where

ceptually anomalous, both offer congruous Yazidis present a problem of legal defi-

methods for the control of territory and nition. Are they non-Muslim or Muslim

women’s sexuality. apostates? Resolving on the former, the

article explains the legalities of their ensla-

these practices rely on historical Muslim vement through a direct link between the

legal norms of sex and captivity found in practice of enslaving Yazidi women and

the nearing of the hour signalling the end

Islamic law manuals

of times evident in the revival of slavery,

its abandonment having occasioned

Historical legal mechanisms for the various forms of immorality.6 The connec-

control of women’s sexuality. as with cap- tion between the revival of slavery and the

tives and slaves, provide the justification end of times is drawn through a hadith or

for captive Yazidi women to be rendered Prophetic tradition,

concubines, similarly for the kidnapping of

more than a hundred Chibok girls to forcibly that one of the signs of the Hour was that

become wives to jihadist soldiers. Although “the slave girl gives birth to her master.”

they are differently interpreted, these prac- This was reported by al-Bukhā rı̄ and

tices rely on historical Muslim legal norms Muslim on the authority of Abū Hurayrah

of sex and captivity found in Islamic law and by Muslim on the authority of ‘Umar

manuals. The justifications for these con- (Dabiq, 2014:15)

temporary enactments of sexuality in war

are not, however, to be found waiting in The laws on enslavement determine that a

the historical texts and innocently revived slave woman who gives birth to her

and re-enacted today. Instead, they are owner’s child is released from the slave

actively produced in present day readings trade, in that she may remain a slave but

of the text, informed by the normativity of may not be traded again, and her child is

sex in the economy of war using modern considered free, i.e. the child has the legal

sexual technologies of the body. Though status of the father and may inherit from

militant Islamists read these narratives out him (Qudū rı̄, 2010). The resultant status of

of classical texts, they also read these narra- umm-walad (a slave mother of a child of a

tives in the present, in a global context free father) is a form of release from

30 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

slavery since the law renders the umm-

article

ISIS trade in women is a particularly

walad free on the death of her owner. modern form of concubinage that allows

Amongst the narratives emerging from the management of women’s reproduction

escaped Yazidi women is that slavery in the through contemporary contraceptive prac-

caliphate is marked by meticulous contra- tices, including pregnancy tests, contracep-

ceptive practices. The stories of escaped tive injections and pills and safe

women indicate that combatants ensure terminations, facilitated by the efficacy of

the women do not become pregnant these technologies.8

through various forms of forced contracep-

Therefore, while Dabiq first argues for re-

tion. One woman described how she was

establishing slavery as an indication of the

forced to take contraceptive pills under

end of times and a necessary aspect of

supervision of her owner, others also

belief, ISIS practises slavery in some

recount forced contraception, pressure to

uniquely contemporary sexual technologies

terminate pregnancies and an instance of

of the body, amongst them the free market

forced termination. Because pregnancy

trade in reliable contraception, reliable

implies a woman may no longer be traded,

testing for pregnancy and safe termination

some women interviewed by the New York

of pregnancy. The efficacy of these technol-

Times said:

ogies render their application particularly

they knew they were being sold when useful in controlling the sexual labour of a

they were driven to a hospital to give a captive slave woman and the strict manage-

urine sample to be tested for the hCG ment of her sexual reproduction.

hormone, whose presence indicates preg- A further uniquely contemporary aspect

nancy. They awaited their results with is the way the historical law on slavery is

apprehension: A positive test would invoked in terms of the affordability of mar-

mean they were carrying their abuser’s riage and in issues of domestic work. In

child; a negative result would allow Dabiq (2014:17), the article explains:

Islamic State fighters to continue raping

them.”7 … a number of contemporary scholars

have mentioned that the desertion of

The absence of pregnancy keeps the women slavery had led to an increase in

in circulation as slaves and avoids their fā hishah (adultery, fornication, etc.),

potential legal freedom from slavery. Classi- because the shar’ı̄ alternative to marriage

cal law on slavery also requires that a is not available, so a man who cannot

women traded between two owners afford marriage to a free woman finds

observe a period of abstinence to establish himself surrounded by temptation

pregnancy or its absence and therewith towards sin. In addition, many Muslim

paternity, such that the sale of a pregnant families who have hired maids to work

slave woman is invalid (Qudū rı̄, 2010). at their homes, face the fitnah of prohib-

Instead, enforced contraception and testing ited khalwah (seclusion) and resultant

for the pregnancy hormone ensures the zinā [adultery] occurring between the

absence of pregnancy in ways that were man and the maid, whereas if she were

not possible in earlier times and restricted his concubine, this relationship would be

under classical law; primarily it allows the legal. This again is from the conse-

owners to trade women without the interim quences of abandoning jihā d and

waiting period. Though unsanctioned, his- chasing after the dunyā (world),

torical slavery practices were not without wallā hul-musta’ā n (and in God we seek

similar manipulations, reflected in literature help). May Allah bless this Islamic State

on induced miscarriage and contraception with the revival of further aspects of the

which allowed slave owners to avoid the religion occurring at its hands.

legal consequences of pregnancy in slave

women (Eich, 2009). What is unique now is Whereas historically war captivity allowed

the modern day efficacy of these sexual for enslavement as a means of sexual subju-

technologies of the body. Without the possi- gation, Dabiq suggests enslavement as a

bility of an interim period of abstinence means of addressing the needs of poor

between owners and the possibility of men. The article argues that those who

freedom through pregnancy, the results of cannot afford the ordinary cost of a dower

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body 31

may either go to war to secure a concubine only other known case – albeit much

article

as booty or they may rather afford the cost smaller – is that of the enslavement of

of a concubine, and further a concubine Christian women and children in the Phi-

might serve better than a domestic worker. lippines and Nigeria by the mujā hidı̄n

Whether this was how slavery actually there. The enslaved Yazidi families are

worked in classical times is known to some now sold by the Islamic State soldiers as

extent, in that the texts often suggest the the mushrikı̄n were sold by the Compa-

first option, marrying a slave woman in nions (radiyallā hu ‘anhum) before them.

case a man cannot afford the dower for a Many well-known rulings are observed,

free woman, the two being historically differ- including the prohibition of separating a

ent.9 The distinction between marrying a mother from her young children (Dabiq,

slave woman and making a woman a concu- 2014:17).

bine is significant, in that the Qur’anic injunc-

tion on slavery does not suggest enslaving Despite or perhaps because of these ‘well

women in order to make licit sex (i.e. mar- observed’ rulings, soon after the Dabiq

riage and concubinage) more affordable. article, the ISIS primer on captives and

This is a different and novel motivation for slaves was prepared in a question and

war in that it argues for enslaving women answer form, familiar to Islamic legal texts.

as war captives in order to facilitate the It is addressed to the fighters and anyone

sexual needs of poor men. else who engages in the trade or use of

enslaved women, establishing the acts of

This explanation indicates a lack of enslavement, and the use of the sexual

knowledge and a novel application of the labour of non-believing women as norma-

historical legalities of the practice of concu- tive aspects of conquest and trade. It

binage. While a concubine may also have begins with a definition that clarifies who is

been required to offer domestic services, a a captive, what constitutes the permissibility

slave purchased for domestic service could of their enslavement and the legalities of sex

not be automatically expected to also with a war captive who has been enslaved,

provide sexual service, so that the slave trading her, ownership shared between two

woman of a wife for example may not be men, terms that prohibit her resale, the

expected to provide sexual service for her dress code of a slave woman, and contracep-

owner’s husband. Her sexual service would tion with an enslaved captive. It concludes

needs-be negotiated through her owner. with the rewards of freeing slave women.

While historical texts suggest a clear distinc- Evidently, the primer is addressed to ques-

tion between domestic service and sexual tioners looking for confirmation that the

service, the manuals often refer to concu- practice has religious legal sanction. What

bines as ‘jariyya’, as Mernissi does above, necessitates the pamphlet is also that the

or ‘sariya’ as we will see later, the author majority of combatants are likely unfamiliar

here seems to make no similar distinction. with these rules or the practice. The

Instead the author sees domestic and authors’ intention is therefore to also offer

sexual services interchangeably, and that is legal and spiritual guidance. If we were to

likely true for most ISIS fighters too. This imagine a questioner, their concern would

is, first, a present day reading of the practice be with the legal or shari’ parameters of an

which is built on little to no actual experience aspect of faith that is no longer in practice

of the practice to build upon, and second it is and so requires confirmation, first that it is

evident that the historical laws of slavery are indeed a legal Islamic practice and second,

not common knowledge amongst ISIS mili- the parameters in which this legality func-

tary. Having been abandoned by main- tions. By contrast, the rules of conduct for

stream Muslim society almost a century sex with slave women are detailed and

ago, only those with a keen interest in the extend into the minutiae that represent the

texts of law might have been familiar with extent to which pre-Islamic and historical

these rules prior to their present revival. cultural norms were subsequently formal-

Accordingly ISIS confirms that, ised in Islamic culture.

[t]his large-scale enslavement of mushrik Reflecting further the lack of knowledge

families is probably the first since the and the limited degrees of compliance, not

abandonment of the Sharı̄’ah law. The long after the release of the question and

32 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

answer manual, a fatwa responds to a ques-

article

sexuality aberrational in that they conflict

tioner who explains that, with contemporary Muslim sexual norms

and values.

… some brothers had committed viola-

tions in the treatment of the female

slaves. These violations are not permitted Sex, consent and desire in

by Shariah law. Because these rules have contemporary Muslim practice

not been dealt with in ages (sic). Are there

Historically, fighters proceeded to war

any warnings pertaining to this matter?

without partners and were familiar with the

possibility of taking enemy captives as

The response focusses again on the legal-

slaves and concubines. With the end of

ities of having sex with captives, when and

slavery in European and western contexts,

how is sex possible with a legal captive,

Muslim communities followed and even-

the processes for ensuring paternity, or

tually terminated the practice to the extent

‘emptiness’ of the womb before a new pur-

that a recent collective statement by promi-

chaser has sex with a slave, the ownership

nent scholars cited a universal Muslim con-

of sisters simultaneously, fathers and sons

sensus against slavery.10 When enacted

owning the same slave and the ownership

today, Muslims who are not aware of the his-

of mother and child simultaneously. An

torical legality of slavery in the Muslim past,

analysis of the enslavement primer and the

find dissonance in the ways in which it might

subsequent fatwa suggest that both docu-

operate. To illustrate the conflict I take up

ments are necessary because the fighters

two online fatwas; they show how the con-

on the frontline are not familiar with these

temporary enactments of classical texts,

laws or practices. While ISIS combatants

concepts and practices are wanting, not

may claim to be following established

only for non-Muslim outsiders, but for

Muslim practices of war, and establishing

Muslims insiders too.

an Islamic State in response to the ‘violation’

of Muslim sovereignty, they cannot claim The first example is from an online forum

equal knowledge of the laws pertaining to where petitioners ask for advice that is deliv-

captivity and sexuality in war. ered in the form of a legal opinion or a

fatwa.11 In March 2014, enslaving women

In the implementation of these laws

for sex was sufficiently prevalent to prompt

through the article in Dabiq, the question

a Muslim man who had been in discussion

and answer manual and the fatwa, rather

with ‘Christian people’ to ask the scholar of

than simply making the ‘historical present’,

the site,

ISIS produces a contemporary iteration of

historical enslavement practices premised

… taking a woman and sleeping with her

upon sexual technologies of the body specific

is not fitting for a God fearing man. I

to a contemporary militarised Muslim mascu-

know that this is a special situation and

linity that relies on sexual control of women

the captives are given by the leader of

and military control of territory.

the Muslims after jihad and it is then per-

The enactment of these classical sexual missible to have sex with them. My ques-

norms in contemporary ways transforms tion is what if a woman refuses, can she

the historical sexual practice, in ways be compelled? I feel almost all women

which are also new to contemporary would hate this situation and few would

Muslim communities, the ISIS combatants accept it except with loathing. Although

amongst them. I argued above that the this is academic, if I was in this situation,

intersection of war and sex is not uncom- I would never force myself on a woman

mon, but is in fact normative in the who did not want me. I of-course accept

modern global context and further, that whatever Islam says about this. Some

through contemporary sexual technologies say 24:33 indicates you cannot compel

of the body, ISIS and Boko Haram style women to have sex but I see this as refer-

militarism enacts contemporary rather ring to prostitution not sleeping with your

than historical forms of military manage- concubine.

ment of sexuality. Hereon I will argue that

the mainstream community of Muslims The questioner is clear that the situation of

also find these new forms of militarised war is a special one, and therefore his

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body 33

concern is not with the legalistic view, since

article

Complete legal capacity is only held in a

he argues that this is “permissible”. His person who has complete control of their

concern is with the matter of consent body and mind. Slavery is premised upon

“what if a woman refuses, can she be the absence of control over the body, since

compelled?” it transfers control of the body and labour

of the slave to another person, including

The answer from the scholars of the site sexual control.12 Therefore to ask the ques-

who is a “graduate of the Umm al-Qurra Uni- tion pertaining to compulsion or consent of

versity in Makkah and the imam at a Jeddah the enslaved person is to ask a question

mosque”: that does not have legal salience. Enslave-

ment by definition removes the requirement

In Islam, we don’t have personas of war for consent. The questioner asks a question

who are put in concentration camps. We that does not apply to the scholar’s legal

have slavery which is a humane way of paradigm, and therefore he cannot answer

treating these prisoners. These prisoners adequately. The scholar cannot answer a

have great rights in Islam. They must eat question of rights from the perspective of a

and wear from what their masters eat system based on impediments to status,

and wear. They can’t be beaten or mis- because the two frames of reference, that

treated as the Prophet salla Allah ualaihi of rights and that of status, are at odds. In

wa sallam saw a man beating his slave his attempt, he can only return to a system

and said to him: remember Allah’s of status to show its benevolence.

power over you. The man set his slave

free for the sake of Allah … Also, he cannot answer to issues of

consent where the premise of control relies

As for the female slave, Islam secured her

on the absence of consent. An analogous

freedom if she bore a child from her

situation occurred in early attempts to

master. Once she does that she can’t be

address marital rape in English law.

sold or given away as her child frees her.

Because the law presumed sexual avail-

She remains a concubine until her

ability to be inherent in the situation of mar-

master dies and then automatically she

riage, a wife’s consent was not a criteria for

is freed. Concubines were found also in

marital sex, and until the close of the last

the previous nations. You can check the

century English law allowed husbands

Bible and you will see that clearly. Pro-

exemption for raping their wives. In 1991

phets of Allah had them such as Ibrahim,

R v R (1991) UKHL 12, declared that under

Jacob, David, Solomon, and many

English law the marital rape exemption did

others. This is not unique thing of Islam.

not apply.13 Many countries continue not to

recognise the possibility of marital rape.

The question speaks through a rights dis-

Similarly, the matter of a slave’s consent to

course to ask about consent, “what if the

sex does not feature in legal terms because

woman refuses, can she be compelled?”

the legal definition of slavery excludes the

and the scholar in response begins in the

capacity to deny consent.

same discourse of rights, “prisoners have

great rights in Islam”. Yet, at the end of his Thus to a second example, which is a

response he has not answered the issues ruling on intercourse with a slave woman

of consent. The reasons for this are poten- when one has a wife.14

tially many, but I will explore the operations

of legal personality and the constitution of Could you please clarify for me something

the legal person, which is markedly different that has been troubling me for a while.

in classical and contemporary understand- This concerns the right of a man to have

ings of Islamic law. Classical scholars sexual relations with slave girls. Is this

employ enslavement as an impediment to so? If it is then is the man allowed to

the realisation of full legal capacity (Qudū rı̄, have relations with her as well his wife/

2010; Jiwan, 1960). While the scholar on wives. Also, is it true that a man can

the site spoke of the rights of a slave, the have sexual relations with any number

deficiency that arises from the status of of slave girls and with their own wife/

slavery renders the enslaved person a differ- wives also? I have read that Hazrat Ali

ent sort of legal subject from the free person, had 17 slave girls and Hazrat Umar also

a slave has incomplete legal capacity. had many. Surely if a man were allowed

34 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

this freedom then this could lead to

article

the fold, to question the legality of the prac-

neglecting the wife’s needs. Could you tice is to question practise of the prophets

also clarify for me whether the wife has as well as the consensus of the scholars.

got any say in the matter.

However, the scholar is unable to assess

the issue of neglect because the question

The questioner refers to the possibility of sex

comes from an understanding of marriage

with a slave, and more so, concern with its

and sexuality which considers both partners

impact on an existing marriage, mostly

to be active sexual agents with the capacity

how this may lead a man to neglecting his

to influence their own and their partner’s

wife, and further the degree to which a

sexual lives. In this paradigm a Muslim

woman may constrain her husband in his

man may not be neglectful of his wife’s

capacity to have sex with a slave woman.

sexual needs and must ensure that she is

The questioner’s assumptions are that sex

sexually satisfied. The scholar and petitioner

should have legal sanction, a wife should

are working with different understandings of

have a say when her husband has sex with

marriage and sexuality. As much as the

a slave woman, and also that it should not

scholar can muster after three more pages

amount to neglect of his wife.

is that “(t)he wife has no right to object to

The response: her husband owning female slaves or to

his having intercourse with them”. The peti-

Praise be to Allah. Islam allows a man to tioner considers the impact of a sexual

have intercourse with his slave woman, relationship with a concubine on the

whether he has a wife or wives or he is relationship with a wife, suggesting the

not married. A slave woman with whom wife’s right to her husband’s attentions and

a man has intercourse is known as a sar- the scholar answers by negating the wife’s

iyyah (concubine), from the word sirr, capacity to object to the arrangement of

which means marriage. This is indicated concubinage.

by the Quraan and the Sunnah, this was

Whereas the dissonance in the ways in

done by the prophets. Ibraheem (pbuh)

which sexuality in the context of slavery

took Haajar as a concubine and she bore

operates in the first fatwa is between classi-

him Isma’eel (peace be upon them all).

cal and contemporary understandings of

Our prophet (peace and blessings of Allah consent, in the second, it pertains to different

be upon him) also did that, as did the concepts of sexuality and marriage, namely

Sahaabah, the righteous and the scholars. a wife’s capacity to restrict her husband’s

The scholars are unanimously agreed on sexuality, and a husband’s obligation

that and it is not permissible for anyone to ensure his fulfillment does not neglect

to regard it as haram or to forbid it. hers.

Whoever regards that as haram is a

sinner who is going against the consen- The easy availability and high levels of effi-

sus of the scholars.

cacy of oral and injectable contraception

means that slave owners can enforce con-

The scholar is Shaykh Muhammad Saalih al-

Munajjid, a popular scholar who established traception on the women they own, manage

the islamqa.info website in 1996. His their fertility and deny it as they choose

response is first to allay the questioner’s

fears on the legality of the sexual relation-

ship, explaining that concubinage has the

status of marriage. The background to this Conclusion

is that the two legal methods for sexual The article has argued that while the sexual

relationships in classical Islamic law, as in practices of ISIS and Boko Haram are con-

many other medieval legal norms, are mar- sidered aberrant to western sexual norms

riage and concubinage (Ali, 2010). While and normative to historical Islamic laws of

the petitioner’s concern is for neglecting war and contemporary Muslim sexual

his wife’s sexual needs, the scholar’s norms, the sexual practices of groups such

concern is with maintaining the legal integ- as ISIS and Boko Haram in fact constitute

rity of concubinage. The last line is important the normative sexual economy of war but

because it chorales the petitioner back into are aberrant both to historical Islamic laws

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body 35

of war and contemporary Muslim norms of

article

mutuality, consent and responsibility to

sexuality, marriage and consent. Through fulfil the desires of their partner. ISIS formu-

the enactment of what is constructed as a lations of sex slavery in its military efforts is

‘historical present’, groups such as ISIS and therefore aberrant both to historical Islamic

Boko Haram purport to the enactment of a legal norms of sex slavery and contempor-

pristine historical past in the present as they ary Muslim understandings of sexuality.

produce a narrative of contemporary Islam While wholly violative it is not however aber-

centred on the intersections of militarism rant to the ways in which sex is otherwise

and sexuality, mediated through narratives factored into the general economy of war

of Muslim piety. However, we see instead where colonial and neo-colonial war efforts

how the sexual economy of militarised Isla- are orchestrated in ways that formulate the

mism combines the caliphate and the nation supply of women’s sexuality into a commod-

state to produce new forms of concubinage ity under control of the military.

using modern sexual technologies of the

body. While historical law produces a

system of sexual slavery that includes possi- Notes

bilities for emancipation, ISIS enactment of 1. I would like to thank the two reviewers for their

sex slavery uses forced contraception and valuable comments and also acknowledge the

termination to ensure that enslaved women various conversations with partners who

offered important insights in the course of

can never release themselves from slavery

writing this article, amongst them Sarojini

through pregnancy. Neither is there the Nadar, Sarasvathie Reddy, Farhana Ismail,

opportunity for reprieve between slave Abdul Karriem Matthews and Mariam Bibi Khan.

owners, instead slave women are passed 2. Drawing on Jacklyn Cock’s (1991) analysis of the

between slave owners without the historical ways in which aggressive masculinities are

requirement for a period of time in which to made normative, Yaliwe Clarke speaks of “mili-

tarised masculinities that are key to militarism”

confirm a woman is not pregnant. The easy (2008:51), and earlier Okazawa-Rey and Kirk

availability and high levels of efficacy of oral (2000:124) also developed Cynthia Enloe’s

and injectable contraception means that (1993) observations on how militarism “relies

slave owners can enforce contraception on on militarised notions of manhood”. Desiree

the women they own, manage their fertility Lewis (2013:26) has in turn proposed reframing

Clarke’s “militarised masculinity” as “gendered

and deny it as they choose.

militarism”, to avoid “a misleading binary of

male prosecutors and women victims”. I have

Sexuality managed in these ways does retained the former for the ways in which it

not find easy resonance outside of mili- speaks to the gendered nature of sex slavery in

tarised Muslim communities where believ- the ISIS and Boko Haram contexts, and which

ers struggle with the implications of sex supports the argument that ISIS and Boko

Haram forms of militarism produce and rely on

with a concubine. Petitioners inquire about

a militarised masculinity.

consent of the concubine, the danger of 3. Available online here: http://www.

neglecting a wife’s sexual needs and the securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-

requirement to fulfil her desires. Couched 6D27–4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/CAC%20S

in the framework of a rights based argu- %20RES%201820.pdf. site accessed 11 Novem-

ment, these concerns jar against the sensi- ber 2016.

4. Aurelia Armstrong (http://www.iep.utm.edu/

bilities of the militarised Islamist who sees foucfem/) draws together the genealogy of

Yazidi women as the reward for his war these concepts from Michel Foucault through

efforts, or military organisers who use glob- Sandra Bartsky to Susan Bordo. Bartsky

ally normative military practices to ensure (1988:77) draws upon Foucault’s “notion of nor-

the supply of sex in the provisions of war. malizing-disciplinary power” as a useful tool

for understanding how societies control

The impossibility of release from sex

women’s bodies; these include disciplinary prac-

slavery through historical guarantees is tices of dieting and body sculpting. Susan Bordo

accompanied by the dissonance between (1988) extrapolates upon these as disciplinary

concubinage as a contemporary form of technologies of the body. I draw upon these

licit sexuality and common understandings ideas to offer an argument for reproductive tech-

of sexuality in marriage. While the historical nologies as sexual technologies of the body used

to discipline the bodies of concubines.

legal paradigm of marriage is sexual control,

5. Women and girls taken captive by Boko Haram

the common understanding of marriage and from Chibok have been referred to as

reflected in the non-military fatwas today ‘wives’ more than concubines.

suggest partners view sex in terms of 6. Dabiq (2014:17) states:

36 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

Before Shaytā n reveals his doubts to the the fatwa also exists in a later publication Islam

article

weak-minded and weak hearted, one Questions and Answers (2004:340), a compi-

should remember that enslaving the families lation edited by Muhammad Saed Abdul-

of the kuffā r and taking their women as con- Rahman.

cubines is a firmly established aspect of the

Sharı̄’ah that if one were to deny or mock,

he would be denying or mocking the

References

verses of the Qur’ā n and the narrations of

the Prophet (sallallā hu ‘alayhiwasallam), Abdul-Rahman MS (2004) Jurisprudence and Islamic

and thereby apostatizing from Islam. Rulings. General and Transactions, Volume 22,

Finally, a number of contemporary scholars Part 1, London: MSA Publication.

have mentioned that the desertion of Adibi H (2006) ‘Sociology of masculinity in the Middle

slavery had led to an increase in fā hishah East’, in Proceedings Social Change in the 21st

(adultery, fornication, etc.), because the Century Conference 2006, Carseldine Campus,

shar’ı̄ alternative to marriage is not avail- Queensland University of Technology, available

able, so a man who cannot afford marriage at: http://eprints.qut.edu.au, accessed 19

to a free woman finds himself surrounded December 2016.

by temptation towards sin. Ali K (2010) Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam,

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University

7. Rukmini Calamachi, ‘To maintain supply of sex Press.

slaves ISIS pushes birth control’, New York Armstrong A (n.d.) ‘Michel Foucault: Feminism’,

Times, 12 March 2016, available at: http://www. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, available

nytimes.com/2016/03/13/world/middleeast/to- at: http://www.iep.utm.edu/foucfem/, accessed

maintain-supply-of-sex-slaves-isis-pushes-birth- 14 December 2016.

control.html?_r=0., accessed 14 December 2016. Bartsky S (1988) ’Foucault, femininity and the modern-

8. In wars amongst nation states, sexual technol- ization of patriarchal power’ in I Diamond & L

ogies used to discipline women’s bodies for the Quinby (eds) Feminism and Foucault:

war efforts are managed by the state’s war Reflections on Resistance, Boston: Northeastern

apparatus. Accordingly, it would be of interest University Press.

for new research to investigate the pathways of Bordo S (1988) ’Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathology

supply and management of contraceptive pills, as the crystallization of culture’ in I Diamond & L

injections and other treatment modalities for Quinby (eds) Feminism and Foucault:

contraception and termination in the caliphate. Reflections on Resistance, Boston: Northeastern

9. Qur’an 4:24 suggests marriage to slave women University Press.

where men cannot marry free women, the Byers JA (2012) ‘The sexual economy of war:

former having a smaller dower. It does not Regulation of sexuality and the U.S. Army, 1898–

suggest enslaving women to facilitate marriage 1940’, Dissertation in the Department of History,

for poor men. Graduate School of Duke University, United States.

10. The online ‘Open Letter to Bhagdadi’, which was Clarke Y (2008) ‘Security sector reform in Africa : a lost

also addressed to “the fighters and followers of opportunity to deconstruct militarised masculi-

the self declared ‘Islamic State’” was signed by a nities?’, in Feminist Africa. 10, 49–66.

group of prominent Muslim scholars, and cited a Eich T. (2009) ‘Induced miscarriage in Early Mā likı̄ and

universal Muslim consensus against the practice Hanafı̄’, in Islamic Law and Society. 16, 3/4, 302–

of slavery. See: http://www.lettertobaghdadi.com, 336.

accessed 2 November 2016. Enloe, CH (1993) The Morning After: Sexual Politics at

11. The website is run by Shaikh Assim al-Hakeem the End of the Cold War, Berkeley: University of

http://www.assimalhakeem.net. The fatwa under California Press.

discussion is available here: https://www.assimal Freamon B (2014) ‘ISIS says Islam justifies slavery:

hakeem.net/the-subject-of-the-women-captives-of- What does Islamic Law say?’ Blog post at CNN

war-has-come-up-in-discussion-with-a-christian/, Freedom Project: Ending Modern-Day Slavery’,

accessed 14 December 2016. available at: http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.

12. See the section on legal capacity (al-Ahliyya) in cnn.com/2014/11/05/isis-says-islam-justifies-

Jiwan (1960). slavery-what-does-islamic-law-say/, site accessed

13. The Law Reports (Appeal Cases) [1992] 1 AC 599, 2 November 2016.

[House of Lords], Regina Respondent and Herzog D (ed) (2008) Brutality and Desire War and

R. appellant 1991 Feb. 27; March 14; 1991 July Sexuality in Europe's Twentieth Century,

1; Oct. 23, available at: http://www.bailii.org/uk/ Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

cases/UKHL/1991/12.html, accessed 14 Decem- ISIS (2014) Newsletter Dabiq Issue 4, in the month of

ber 2016. Dhul Hijja 1435 (CE 26 September-24 October

14. The fatwa was available until early this year as 2014).

fatwa #13082 on the website of the scholar Al- ISIS (2014) ‘Questions and Answers on Captives and

Munajjid here: https://islamqa.info/en. While Slaves’, produced by the Ministry of Research

the original fatwa #13082 is no longer available and Legal Opinion, in the month of Muharram

on the site, a link to the fatwa remains visible in 1436 (CE 25 October-24 November 2014).

another fatwa, #20085: https://islamqa.info/en/ Jiwan M (1960) Nū r al-Anwā r ma‘a ā shı̄yat Qamar al-

20085, accessed 14 December 2016. A copy of Aqmā r, Delhi: Kutub Khanah Rashidiyah.

Sexual economies of war and sexual technologies of the body 37

Lewis D (2013) ‘The multiple dimensions of human Law According to the Ḥ anafı̄ School, translated

article

security through the lens of African feminist intel- by Ṭ ā hir Maḥ mood Kiā nı̄, London: Ta-Ha.

lectual activism’, in Africa Peace and Conflict Rey MI (2016) ‘Reexamination of the foreign female

Journal, 6, 1, 15–28 captive: Deuteronomy 21:10–14 as a case of gen-

Makepeace C (2013) ‘Punters and their prostitutes: ocidal rape’, in Journal of Feminist Studies in

British soldiers, masculinity and maisons Religion, 32, 1, 37–53.

tolérées in the First World War’ in JH Arnold & S Roberts ML (2013) What Soldiers Do: Sex and the

Brady (eds) What is Masculinity? Historical American GI in World War II France, Chicago:

Dynamics from Antiquity to the Contemporary University of Chicago Press.

World, London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, Salvatore A (2016) The Sociology of Islam:

Mernissi F (1996) Women’s Rebellion and Islamic Knowledge, Power and Civility, Malden MA;

Memory, London, UK: Atlantic Highlands, New Oxford UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Jersey: Zed Books, United University Press.. Sommer R (2009) Das KZ-Bordell: sexuelle

Milano V (n.d) ‘Wehrmacht Brothels’, Der Eerst Zug, Zwangsarbeit in nationalsozialistischen

first published in Die Neue Feldpost newsletter, Konzentrationslagern, Paderborn: Schö ningh.

available at: http://www.dererstezug.com/ Sun X (2014) ‘Chinese Comfort Women:

WehrmachtBrothels.htm, site accessed 1 Testimonies from Imperial Japan’s Sex

December 2016: Slaves. Peipei Qiu, with Su Zhiliang and

Moon S (2015) ‘Sexual labor and the U.S. military Chen Lifei, Vancouver: University of British

empire: comparative analysis of Europe and Columbia Press’, in The China Quarterly,

East Asia’ in DE Bender & JK Lipman (eds) 220, 1148–1149. Doi:10.1017/S0305741014

Making the Empire Work: Labor and United 001283

States Imperialism, New York; New York Trewhela P (1993a) ‘Mrs Mandela, ’Enemy agents!’ …

University Press. and the ANC Women’s League’, in Searchlight

Okazawa-Rey M & Kirk G (2000) ‘Maximum Security’, South Africa, 3, 3, 17–22.

in Social Justice, 3, 81, 120–32. Trewhela, P (1993b)’Women and SWAPO institutiona-

Qudū rı̄ AM (2010) The Mukhtaṣar of Imā m al-Qudū rı̄ al- lised rape in SWAPO’s prisons’, in Searchlight

Baghdā dı̄ (362 AH-428 AH): A Manual of Islamic South Africa, 3, 3, 23–29.

FATIMA SEEDAT lectures in the Gender and Religion Programme at the

University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) where she also coordinates the

Masters programme in Gender, Religion and Sexual and Reproductive

Health Rights. Prior to this she held an Innovation Fund Post-Doctoral

Fellowship in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of

Cape Town, an NRF Equity Scholarship for Doctoral Studies Abroad at

the Institute of Islamic Studies at McGill University, Canada, and a

Chevening Fellowship at the Human Rights Law Center at University of

Nottingham, United Kingdom. She holds a PhD in Islamic Law from

McGill University where, through a study of legal capacity in Islamic jur-

isprudence, she investigated the discursive construction of women as

legal subjects. She has also published on the politics of the convergence

of Islam and feminism. Outside of academia, she has worked for the Com-

mission on Gender Equality, at the Women’s and Children’s Rights Desk

of the Department for International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO),

co-founded Shura Yabafazi, a South African NGO that focuses on sex

difference in Muslim family law and consulted on criminal law reform

for UNWomen Afghanistan.

Email: Seedatf@ukzn.ac.za

38 AGENDA 109/30.3 2016

View publication stats

You might also like

- Prospectus For Admission To B Ed Degree Programmes in Affiliated Colleges Through Centralised Allotment Process (Cap)Document33 pagesProspectus For Admission To B Ed Degree Programmes in Affiliated Colleges Through Centralised Allotment Process (Cap)Melvin MathewNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Compromise: A Solution To India's Delimitation Dilemma?Document3 pagesThe Cambridge Compromise: A Solution To India's Delimitation Dilemma?Melvin MathewNo ratings yet

- "God Cannot Keep Silent" Strong Religious-Nationalism Theory and PracticeDocument26 pages"God Cannot Keep Silent" Strong Religious-Nationalism Theory and PracticeMelvin MathewNo ratings yet

- The Delimitation Commission Act - 1962Document8 pagesThe Delimitation Commission Act - 1962Melvin MathewNo ratings yet

- The National Commission For Women: Breif HistoryDocument5 pagesThe National Commission For Women: Breif HistoryMelvin MathewNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Expansionism Monroe DoctrineDocument23 pagesExpansionism Monroe Doctrineapi-3699641No ratings yet

- Correct SpellingDocument4 pagesCorrect SpellingMicaEscoNo ratings yet

- GSTR3B 33abppc1495f1zs 052023Document3 pagesGSTR3B 33abppc1495f1zs 052023Arun Nahendran SNo ratings yet

- Republic v. TuveraDocument16 pagesRepublic v. Tuveraxsar_xNo ratings yet

- 35 Philippine Dream Company Inc. V.20210424-12-1jxqs4iDocument11 pages35 Philippine Dream Company Inc. V.20210424-12-1jxqs4iervingabralagbonNo ratings yet

- Uncitral Model Laws On E-CommerceDocument6 pagesUncitral Model Laws On E-CommerceKavya Prakash0% (1)

- HIGHLIGHTS OF THE READING On Retraction of RizalDocument4 pagesHIGHLIGHTS OF THE READING On Retraction of RizalDianne Mae LlantoNo ratings yet

- Code of Conduct For Teachers in Sierra LeoneDocument20 pagesCode of Conduct For Teachers in Sierra LeoneIbrahim KalokohNo ratings yet

- Get Richer Sleepinge BookDocument23 pagesGet Richer Sleepinge BookRaiyan Shifty100% (1)

- Dipankar Gupta Hierarchy and DifferencesDocument28 pagesDipankar Gupta Hierarchy and DifferencesPradip kumar yadav100% (3)

- Ocampo vs. Rear Admiral EnriquezDocument51 pagesOcampo vs. Rear Admiral EnriquezLyna Manlunas GayasNo ratings yet

- Hi 104 Seminar Questions 2017-2021Document2 pagesHi 104 Seminar Questions 2017-2021komando kipensi100% (2)

- Business Vocabulary BuilderDocument178 pagesBusiness Vocabulary BuilderDanik ZuNo ratings yet

- Admission of A PartnerDocument5 pagesAdmission of A PartnerHigreeve SrudhiNo ratings yet

- Practical Strategies For Technical Communication With 2016 Mla Update 2nd Edition Markel Solutions ManualDocument6 pagesPractical Strategies For Technical Communication With 2016 Mla Update 2nd Edition Markel Solutions Manualbarrydixonydazewpbxn100% (17)

- Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument43 pagesMotion For Summary JudgmentLisa Lisa100% (4)

- Federal CybersecurityDocument47 pagesFederal CybersecurityAdam JanofskyNo ratings yet

- Political TheoryDocument14 pagesPolitical TheoryacostaannexyrineNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines V. Henry Arpon Y JuntillaDocument6 pagesPeople of The Philippines V. Henry Arpon Y JuntillasophiaNo ratings yet

- CRIME MAPPING C-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesCRIME MAPPING C-WPS OfficeIvylen Gupid Japos CabudbudNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Apollo HospitalsDocument9 pagesCritical Analysis of Apollo Hospitalsakashkr619No ratings yet

- Here - and There - WordsDocument4 pagesHere - and There - WordsCami FunesNo ratings yet

- Dirty BertieDocument30 pagesDirty Bertienmg0024100% (8)

- Bodal Chemicals LTDDocument4 pagesBodal Chemicals LTDNidhi KaushikNo ratings yet

- Soliya Reflection FinalDocument8 pagesSoliya Reflection FinalRob GloverNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 TVM and Interest ConceptDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 TVM and Interest ConceptKHANSA DIVA NUR APRILIANo ratings yet

- Civil Court and Code of Civil ProcedureDocument17 pagesCivil Court and Code of Civil ProcedureShubhankar ThakurNo ratings yet

- Revised and Updated Eagle Scout Application Form 2022 RIZAL COUNCIL NOESIGN - Docx 1Document2 pagesRevised and Updated Eagle Scout Application Form 2022 RIZAL COUNCIL NOESIGN - Docx 1tulabingiverson23No ratings yet

- Belgium Checklist For Study Visa - Article 9: Visa D - Long StayDocument2 pagesBelgium Checklist For Study Visa - Article 9: Visa D - Long StayMoin Ul HassanNo ratings yet

- Potsdam Police Blotter April 15, 2017Document3 pagesPotsdam Police Blotter April 15, 2017NewzjunkyNo ratings yet