Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gender Roles: How Children Learn Stereotypes

Uploaded by

Rachel Stewart0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesChildren begin to be influenced by gender stereotypes from a very young age through subtle cues from parents and society. Parents often use gendered language for their unborn children and decorate nurseries in gendered ways. By age 2, children prefer gender stereotypical toys and colors. They also begin to police their own behavior and the behavior of others to conform to stereotypes. However, studies also show that exposure to counter-stereotypical ideas through books or parents can help children develop less rigid views of gender roles.

Original Description:

Original Title

Children and Genderfd

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentChildren begin to be influenced by gender stereotypes from a very young age through subtle cues from parents and society. Parents often use gendered language for their unborn children and decorate nurseries in gendered ways. By age 2, children prefer gender stereotypical toys and colors. They also begin to police their own behavior and the behavior of others to conform to stereotypes. However, studies also show that exposure to counter-stereotypical ideas through books or parents can help children develop less rigid views of gender roles.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesGender Roles: How Children Learn Stereotypes

Uploaded by

Rachel StewartChildren begin to be influenced by gender stereotypes from a very young age through subtle cues from parents and society. Parents often use gendered language for their unborn children and decorate nurseries in gendered ways. By age 2, children prefer gender stereotypical toys and colors. They also begin to police their own behavior and the behavior of others to conform to stereotypes. However, studies also show that exposure to counter-stereotypical ideas through books or parents can help children develop less rigid views of gender roles.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Children and Gender

By Rachel Stewart

What is “gendering”? This was in direct opposition to their parents’ stated

For most of us, gender appears synonymous with our beliefs.9

biological sex and believe that this part of our identity

was formed from birth. However, researchers have Who is responsible for applying gender?

found key differences between the two. Sex is defined Most often, gender stereotypes are enforced, perhaps

by the physical and biological attributes of a person, XX unintentionally, by parents. Parents begin assigning

chromosomes for girls and XY for boys.1 Gender is gender to their unborn children by use of blue and pink

defined by society, based on the characteristics and gendered pronouns.10 This continues throughout

considered appropriately masculine or feminine.2 Sex is adolescence. Parents often adjust the expectations of

defined at or before birth, whereas children will begin their child based on gender.11 Math is one such

to identify with a gender by the age of four. 3 What does example; regardless of test scores, parents often

the formation of gender mean in terms of young associate gender with competence in math. These same

children’s identities and futures? researchers found that English and sports were the

same. Parents of daughters were more likely to

When are children gendered? attribute competence in English to their children, while

Although children may be four years old before they parents of boys expressed a belief of sports ability. 12

begin to define themselves by gender, researchers Perhaps most obviously, manufacturers perpetuate

found that parents and family members begin to do so gendered stereotypes. Toys that used to be gender-

while the child is still in utero, according to one study. neutral, such as crayons or building blocks, now come

Due to the popularity of ultrasound technology, parents in “boy” and “girl” styles.13 One expert states that girls’

may know the sex of their child as early as 16 weeks. toys are correlated with domesticity, nurturing, and

After a pregnant woman learns the sex of her fetus, physical attractiveness, while boys’ toys are viewed as

researchers found that she begins using gendered competitive and violent.14 Gendered toys have been

language in conversation (“he” or “she”) and towards increasing in number, since approximately 1915. 15

her own womb, including naming the fetus. The study

Fact File

noted that parents will often paint the nursery pink or

blue, buy gendered clothing, and change expectations

for their fetus based on sex.4 Before 1915, there were no truly gender-specific

Children begin to understand gender roles as early as

toys marketed to children in the Sears catalog,

24-months.5 This is the same age as when they begin to

understand the biological differences between males

including dolls.16

and females.6 In a recent study, researchers observed

children viewing people performing tasks. They Previous to the 19th century, gender-neutral

measured the amount of time each child would spend clothing was normal for children up to age 7.17

looking at the performer. Children who witnessed

gender inconsistent activities spent more time When specific gender colors came into fashion in

watching the performer than those who completed the early 20th century, pink was considered the

gender consistent activities. 18-month-olds were also more masculine color and was marketed to boys. 18

tested, but there was no discernible difference between

times.7

In 1985, there was a rebellion against gendered

By the age of 3-5, children can identify “boy” and

toys. The Sears catalog advertised girls’ action

“girl” toys.8 In a study, children were asked to identify

toys and predict their parents’ approval or disapproval figures and boys modeled the toy vacuum

based on whether the toy was gender-appropriate. cleaners.19

Most often, children predicted approval for gender

appropriate toys and disapproval for cross-gender play. Interestingly, children themselves often enforce

gender stereotypes. Once children begin to gain a sense

of gender, usually around the age of five, they enter a

period of black and white thinking around gender.20

Later in adolescence, this rigidity loosens. Once

children have an understanding

of gender stereotypes, they begin to apply them to

themselves and their preferences.21

How is gender asserted in early childhood?

Studies have shown that blue is the most often

preferred color for children, regardless of gender.

However, by the age of two for girls and two and a half

for boys, color begins to have a gendered aspect. Girls

began to show preference for pink and boys avoided

it.22

In one study, children showed a gendered preference

for crayons when coloring figures. Researchers found

that boys avoided using pink, even when coloring

female figures, while girls used both masculine and

feminine colors. However, they used fewer feminine

colors on a male figure.23

Is gender stereotyping permanent?

Children are influenced by the books they are

exposed to, concludes one study. Researchers found

that when children read stories that contain “gender-

atypical” behavior, there is an increased desire to play

with atypical toys and displays of

atypical behaviors. Children continue this behavior

beyond the immediate time frame of the stories,

including affecting future goals and plans.24

Additionally, children are affected by their parents’

attitudes toward gender. Though parents claimed to

support their children in cross-gender play, more than

one fourth said that they would not hire a male

babysitter.25 In the same questionnaire, only 46% of

respondents said they would buy the same toys for

both sons and daughters, and only 10% more claimed

they would purchase their son a doll. Through their

responses, these parents expressed some level of

discomfort in boys performing “feminine” activities,

more so than girls performing “masculine” activities.26

In households where parents equally share housework

and childcare, children show less gender stereotyping

in preschool years than those from traditional

families.27 This suggests that parents have the ability to

form their children’s responses to gender.

In sum, children’s gender identity is a flexible and

delicate thing that creates ripples into the future. We as

a society are responsible for each child’s experience of

gender and must take care to create a positive

environment that fosters possibilities for all.

1

Notes

Gender Identity Development in Children. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-

stages/gradeschool/Pages/Gender-Identity-and-Gender-Confusion-In-Children.aspx

2

Crawford, M. (2012). Transformations: Women, Gender & Psychology (2nd Ed.). New York, NY; McGraw Hill.

3

Gender Identity Development in Children. (2015).

4

Barnes, M.W. (2014). Anticipatory Socialization of Pregnant Women: Learning Fetal Sex and Gendered Interactions.

Sociological Perspectives, 58:2. doi: 10.1177/0731121414564883

5

Hill, S.E. & Flom, R. (2007). 18- and 24-month-olds’ discrimination of gender consistent and inconsistent activities.

Infant Behavior and Development, 30:1, 168-173. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.08.003

6

Gender Identity Development in Children. (2015).

7

Ibid.

8

Freeman, N. K. (2007). Preschoolers' Perceptions of Gender Appropriate Toys and Their Parents' Beliefs about

Genderized Behaviors: Miscommunication, Mixed Messages, or Hidden Truths? Early Childhood Education Journal,

35, 357-366. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.sdsu.edu/10.1007/s10643-006-0123-x

9

Ibid.

10

Barnes, M.W. (2014).

11

Eccles, J. S., Jacobs, J. E. and Harold, R. D. (1990), Gender Role Stereotypes, Expectancy Effects, and Parents'

Socialization of Gender Differences. Journal of Social Issues, 46: 183–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01929.x

12

Ibid.

13

Sweet, E. (2011). The “Gendering” of Our Kids’ Toys, and What We Can Do About It. Retrieved from

https://www.newdream.org/blog/2011-10-gendering-of-kids-toys

14

Ibid.

15

Ibid.

16

Sweet, E. (2011).

17

Maglaty, J. (2011). When Did Girls Start Wearing Pink? Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/when-did-girls-start-wearing-pink-1370097/?no-ist

18

Ibid.

19

Sweet, E. (2011).

20

Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D.. (2004). Children's Search for Gender Cues: Cognitive Perspectives on Gender

Development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13:2, 67–70. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182912

21

Ibid.

22

LoBue, V. & DeLoache, J. S. (2011), Pretty in pink: The early development of gender-stereotyped colour

preferences. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 29: 656–667. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02027.x

23

Karniol, R. (2011). The Color of Children’s Gender Stereotypes. Sex Roles, 65, 119-132. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-

9989-1

24

Abad, C., & Pruden, S. M. (2013). Do storybooks really break children’s gender stereotypes? Frontiers in

Psychology, 4, 986. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00986

25

Freeman, N. K. (2007).

26

Ibid.

27

Crawford, M. (2012).

You might also like

- Modefying GenderDocument8 pagesModefying Genderwaleedms068467No ratings yet

- Gender Is It A Social Construct or A Biological InevitabilityDocument5 pagesGender Is It A Social Construct or A Biological InevitabilitySaurabhChoudharyNo ratings yet

- PSYC-320A Dist-Ed Lecture 4Document54 pagesPSYC-320A Dist-Ed Lecture 4raymondNo ratings yet

- De La Salle University College of Liberal Arts Department of PsychologyDocument23 pagesDe La Salle University College of Liberal Arts Department of PsychologyMark BlandoNo ratings yet

- Parents' Socialization of Gender in ChildrenDocument4 pagesParents' Socialization of Gender in ChildrenGian SurbanoNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles in Childhood: A Study on Kohlberg's TheoryDocument23 pagesGender Roles in Childhood: A Study on Kohlberg's TheoryMark BlandoNo ratings yet

- Gender Specific ToysDocument11 pagesGender Specific ToysJocee SykesNo ratings yet

- Gender Role DevelopmentDocument3 pagesGender Role DevelopmentWenie CanayNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography - EditedDocument13 pagesAnnotated Bibliography - EditedMoses WathikaNo ratings yet

- FAMILYDocument6 pagesFAMILYKharlyn MengoteNo ratings yet

- Psy512 CH 17Document6 pagesPsy512 CH 17mayagee03No ratings yet

- What Is MaleDocument6 pagesWhat Is MaleBudi PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Sexual Knowledge of Preschool Children: Renate Volbert, PHDDocument22 pagesSexual Knowledge of Preschool Children: Renate Volbert, PHDLisa RucquoiNo ratings yet

- A Bra Ha MyDocument7 pagesA Bra Ha MyKelly OrtizNo ratings yet

- 3 Gender Cognitive Explanations of Gender DevelopmentDocument8 pages3 Gender Cognitive Explanations of Gender DevelopmentFN IS MOISTNo ratings yet

- Healthy Gender DevelopmentDocument20 pagesHealthy Gender DevelopmentMoumi DharaNo ratings yet

- TwinshipDocument11 pagesTwinshipapi-253069785No ratings yet

- A Joosr Guide to... Delusions of Gender by Cordelia Fine: The Real Science Behind Sex DifferencesFrom EverandA Joosr Guide to... Delusions of Gender by Cordelia Fine: The Real Science Behind Sex DifferencesNo ratings yet

- Sex Differences: A Study of The Eye of The BeholderDocument9 pagesSex Differences: A Study of The Eye of The BeholderMiriam BerlangaNo ratings yet

- Gender Essentialism in Transgender and Cisgender CDocument12 pagesGender Essentialism in Transgender and Cisgender CLaura Núñez MoraledaNo ratings yet

- Agents of SocializationDocument5 pagesAgents of SocializationFarheen RashidNo ratings yet

- Gender Transition ChildrenDocument5 pagesGender Transition ChildrenbrianNo ratings yet

- Do Parents Have Different Hopes and Standards For Their Sons Than For Their DaughtersDocument3 pagesDo Parents Have Different Hopes and Standards For Their Sons Than For Their DaughtersAlina MorarNo ratings yet

- Gender Early SocializationDocument27 pagesGender Early SocializationNat LindsayNo ratings yet

- M2. Normative Sexual Behavior in Children. A Contemporary Sample.Document10 pagesM2. Normative Sexual Behavior in Children. A Contemporary Sample.Azahara Calduch100% (1)

- DgweldlitrivewDocument7 pagesDgweldlitrivewapi-285774840No ratings yet

- ProposalDocument11 pagesProposalapi-302389888No ratings yet

- Pro Same Sex Adoption DraftDocument6 pagesPro Same Sex Adoption Draftapi-292753226No ratings yet

- Parental Influence on Children's Socialization to Gender RolesDocument7 pagesParental Influence on Children's Socialization to Gender RolesSameet Kumar MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Gender Enculturation: How We Learn Our Gender Roles in SocietyDocument2 pagesGender Enculturation: How We Learn Our Gender Roles in SocietyShilpa HarinarayananNo ratings yet

- Children With LPsDocument14 pagesChildren With LPsSrishtyNo ratings yet

- Sexdifferencesinchildrenstoypreferencesmeta analysisWordVersionDocument68 pagesSexdifferencesinchildrenstoypreferencesmeta analysisWordVersionJohn Erick Von Ribbentrop FerrerNo ratings yet

- Sample Reaction PaperDocument1 pageSample Reaction Paperjasonmscofield63% (8)

- Where Do Babies Come FromDocument14 pagesWhere Do Babies Come FromMV FranNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Intersection of Gender, Identity, and SexualityFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Intersection of Gender, Identity, and SexualityNo ratings yet

- Final Draft Essay 2Document9 pagesFinal Draft Essay 2api-341639651No ratings yet

- Lewis-Lamb 2003 - Fathers' Influences On Children's DevelopmentDocument18 pagesLewis-Lamb 2003 - Fathers' Influences On Children's Developmentİnanç EtiNo ratings yet

- Effects of Same-Sex ParentingDocument15 pagesEffects of Same-Sex ParentingveeaNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes and RolesDocument29 pagesGender Stereotypes and Rolesakhilav.mphilNo ratings yet

- The Truth About Girls and Boys: Challenging Toxic Stereotypes About Our ChildrenFrom EverandThe Truth About Girls and Boys: Challenging Toxic Stereotypes About Our ChildrenNo ratings yet

- PersuasiveDocument7 pagesPersuasiveapi-217229118No ratings yet

- Are Children SexualDocument18 pagesAre Children SexualBelén CabreraNo ratings yet

- Sex Stereotyping in Children's Toy AdvertisementsDocument14 pagesSex Stereotyping in Children's Toy AdvertisementsHanna GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- LoBue & DeLoache, 2011 PDFDocument12 pagesLoBue & DeLoache, 2011 PDFJosé Carlos MéloNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT - Homossexual ParetingDocument5 pagesABSTRACT - Homossexual ParetingWork FilesNo ratings yet

- Sex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case StudyDocument8 pagesSex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case Studyapi-99042879No ratings yet

- AQA A Level Psychology Option Companion Gender SampleDocument4 pagesAQA A Level Psychology Option Companion Gender SampleMyra JainNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDF123455690210No ratings yet

- Stereotypical and prosocial behaviors in childrenDocument4 pagesStereotypical and prosocial behaviors in childrentaylor swiftyyyNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Stereotypical and Prosocial BehaviorsDocument4 pagesRunning Head: Stereotypical and Prosocial Behaviorsjohn lenard claveriaNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFOanna AnnaoNo ratings yet

- Stereotypical and prosocial behaviors in childrenDocument4 pagesStereotypical and prosocial behaviors in childrenJerelyn BayaNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFMelChristian CastilloNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFMark24 AntonioNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFIcia Carranza CasNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFFranklin AlngagNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFHaraden GioNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFRyan Jhon SeguraNo ratings yet

- Behaviors PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviors PDFJerelyn BayaNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles: How Children Learn StereotypesDocument3 pagesGender Roles: How Children Learn StereotypesRachel StewartNo ratings yet

- Diet & Supplementation Guide for EDSDocument49 pagesDiet & Supplementation Guide for EDSRachel StewartNo ratings yet

- Autism in Girls ChecklistDocument3 pagesAutism in Girls ChecklistMarina MinariNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles: How Children Learn StereotypesDocument3 pagesGender Roles: How Children Learn StereotypesRachel StewartNo ratings yet

- The Pathology of Raised Intracranial PressureDocument3 pagesThe Pathology of Raised Intracranial PressureRachel StewartNo ratings yet

- Ceramics Self Crit Spring 2018Document1 pageCeramics Self Crit Spring 2018Rachel StewartNo ratings yet

- Bringing Class to Mass: L'Oreal's Plénitude Line Struggles in the USDocument36 pagesBringing Class to Mass: L'Oreal's Plénitude Line Struggles in the USLeejat Kumar PradhanNo ratings yet

- MDD FormatDocument6 pagesMDD FormatEngineeri TadiyosNo ratings yet

- Audit of Intangible AssetDocument3 pagesAudit of Intangible Assetd.pagkatoytoyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21 I Variations ENHANCEDocument21 pagesChapter 21 I Variations ENHANCENorazah AhmadNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineering Softwares and Their ImplementationsDocument13 pagesCivil Engineering Softwares and Their ImplementationsADITYANo ratings yet

- Simple BoxDocument104 pagesSimple BoxTÙNGNo ratings yet

- Eight Lane Vadodara Kim ExpresswayDocument11 pagesEight Lane Vadodara Kim ExpresswayUmesh SutharNo ratings yet

- Research Day AbstractsDocument287 pagesResearch Day AbstractsStoriesofsuperheroesNo ratings yet

- Hydrolics Final Year ProjectDocument23 pagesHydrolics Final Year ProjectHarsha VardhanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-12 Direct and Inverse ProportionsDocument22 pagesChapter-12 Direct and Inverse ProportionsscihimaNo ratings yet

- Media ExercisesDocument24 pagesMedia ExercisesMary SyvakNo ratings yet

- The Law of DemandDocument13 pagesThe Law of DemandAngelique MancillaNo ratings yet

- Soften, Soothe, AllowDocument1 pageSoften, Soothe, AllowTatiannaMartinsNo ratings yet

- What does high frequency mean for TIG weldingDocument14 pagesWhat does high frequency mean for TIG weldingUmaibalanNo ratings yet

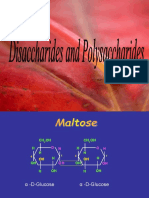

- Disaccharides and PolysaccharidesDocument17 pagesDisaccharides and PolysaccharidesAarthi shreeNo ratings yet

- Dec50103 PW2 F1004Document14 pagesDec50103 PW2 F1004Not GamingNo ratings yet

- New Life in Christ by Wilson HerreraDocument18 pagesNew Life in Christ by Wilson Herreralesantiago100% (1)

- 1 HeterogenitasDocument46 pages1 HeterogenitasRani JuliariniNo ratings yet

- The Open Banking StandardDocument148 pagesThe Open Banking StandardOpen Data Institute95% (21)

- Energy Savings White PaperDocument14 pagesEnergy Savings White PapersajuhereNo ratings yet

- Creutzfeldt JakobDocument6 pagesCreutzfeldt JakobErnesto Ochoa MonroyNo ratings yet

- Why I Am Not A Primitivist - Jason McQuinnDocument9 pagesWhy I Am Not A Primitivist - Jason McQuinnfabio.coltroNo ratings yet

- Thesis FormatDocument10 pagesThesis FormatMin Costillas ZamoraNo ratings yet

- ADP Pink Diamond Investment Guide 2023Document47 pagesADP Pink Diamond Investment Guide 2023sarahNo ratings yet

- IBM Global Business ServicesDocument16 pagesIBM Global Business Servicesamitjain310No ratings yet

- 9 - The Relationship Between CEO Characteristics and Leverage - The Role of Independent CommissionersDocument10 pages9 - The Relationship Between CEO Characteristics and Leverage - The Role of Independent Commissionerscristina.llaneza02100% (1)

- MAXScript EssentialsDocument20 pagesMAXScript EssentialsSebastián Díaz CastroNo ratings yet

- Nurses' Knowledge and Practice For Prevention of Infection in Burn Unit at A University Hospital: Suggested Nursing GuidelinesDocument8 pagesNurses' Knowledge and Practice For Prevention of Infection in Burn Unit at A University Hospital: Suggested Nursing GuidelinesIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- 5 Set Model Question Mathematics (116) MGMT XI UGHSSDocument13 pages5 Set Model Question Mathematics (116) MGMT XI UGHSSSachin ChakradharNo ratings yet