Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Uricchio - Film History 7 - Archives and Absences

Uploaded by

Carolina Del ValleOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Uricchio - Film History 7 - Archives and Absences

Uploaded by

Carolina Del ValleCopyright:

Available Formats

Archives and Absences

Author(s): William Uricchio

Source: Film History, Vol. 7, No. 3, Film Preservation and Film Scholarship (Autumn, 1995),

pp. 256-263

Published by: Indiana University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3815092 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 01:02

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FilmHistory,Volume7, pp. 256-263, 1995. Copyright?John Libbey&Company

ISSN:0892-2160. PrintedinGreatBritain

Archives and

absences

WilliamUricchio

R eceived wisdom holds that virtualre- lookingat the situationfromthe archivists'perspec-

ality seeks to create an ever more pre- tive - the recurrenthistoricalproblemsof agency

cise simulationof the physical world, and narrativeplay a minor role in acquisition,

somethingakin to its exact replication. cataloguing and preservation,but the virtualre-

Butthe increasingfeasibilityof virtualreality'stech- alityanalogy raises intriguingquestionsabout the

nological fulfilmentthreatensan epistemological constructionsof the past that can be extrapolated

crisisinwhichthe issueof greatestimportbecomes from necessarilylimitedarchival holdings. In the

not sameness or mimesis, but the difference be- pages thatfollow, Iwouldliketo reflecton some of

tween thevirtualworldand the 'real'world.Virtual the archivalexperienceswhich have informedmy

reality,extrapolatedto its fullestpointof develop- research,paying attentionto the shiftingfabricof

ment,is far moresignificantforwhat it cannotde- constraintsthat have veiled and shaped access to

liver;as a discourseon the limitsof representation the events of the past. Threetypes of structuring

it offersa compellingmeditationon the natureof limitationswill be discussed:overt policies which

ontology.And so it is witharchives,at leastfroma restrictaccess to otherwise available material;

structuralperspective.Scholarsdraw uponvarious overt policies which define and restrictthe very

archival holdings to constructrepresentationsof collectionof material;and, the general historical

the past, as tellingfor theirlimitationsas for their filtrationprocesseswhich, by preservingsome rec-

'completeness'.As withvirtualreality,the effortat ords and ignoringothers,shape the archivalrec-

totalizationteaches us as muchabout the limitsof ord every bit as effectivelyif far less overtly.

representationas aboutthe eventrepresented.

Thissort of discussionobviouslydraws upon

From controlled access to censorship

contemporarydebates in the field of culturalhis-

tory, particularlythose regardingthe (contingent) In the course of an extended visit to the Federal

natureof representation.Issuesranging fromthe Republicof Germany'sBundesarchivin Koblenz,I

unstablenatureof facticity,to the balance between came across severaldocumentsin the UFA-Kultur-

determinantstructure and individualagency, to the filmfilesof the mid-i930s whichdiscussedthe sale

place of the researcher'ssubjectivityin the con- and productionof films for televisionexhibition.

structionof historicalnarratives,have all under- The documentswere intriguingas muchfor what

minedtraditionalhistoriographicassumptionsand they revealedabout UFA'svision of its own future

invigoratedthe self-consciousinterrogationof the as for what they suggested about a largely unex-

historicalprocess'. Thenature,form,and implica- plored period in television history.Althoughmy

tionsof the residuesof the past accumulatedin the primary research task during that visit centred

historicalrecordsthat we commonlytake as 'evi- aroundnon-fictionfilmtypologiesand production

dence', while notalways centralto these debates,

have neverthelessplayed a crucialif implicitrolein

William Uricchiois Professor

of FilmandTelevi-

thedeploymentof historicalarguments.Of course, sionatUtrecht Contact: Filmand

University. Theatre,

scholarsemploy archivalrecordsfor purposesfar TelevisionStudies,UtrechtUniversity,Kromme

exceeding 'mere' representation,and - at least Nieuwegracht29, 3512 HDUtrecht, Netherlands.

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and absences

Archivesand

Archives absences257 257

patterns,IcollectedwhattelevisionmaterialIcould Despitethe readyavailabilityof recordsoften

find and meanwhile checked more obvious unavailableto researchersof othernationalbroad-

sourcesto fill the evidentgaps in my knowledge. cast histories,myGermantelevisionprojectfaced

ThepreliminaryresearchI accomplishedrevealed sometimessevere archivaldifficultiesfora number

that popular(or even scholarly)memoryhad ac- of reasons, the firstrelatingto initialacquisition

cordedvery littleacknowledgementto the consid- and cataloguingdecisions. Before1944, the Ger-

erable development that German television man governmentdivided oversight of television

underwentbetween 1935 and 1944. The more among three ministries,the postal authoritiesre-

closely I looked, the more I became intriguedby sponsiblefortechnologicaldevelopments,the pro-

the subjectof Germany'stelevisionhistory- a his- paganda authoritiesfor programming,and the air

tory marginalizedeven within the massive (and ministryforpotentialmilitarycapabilities.Rivalries

otherwiseimpressive)televisionstudyprojectcen- withinand among these agencies inflectedthe pro-

tredat the Universityof Siegen. Thiscloser investi- ductionand archivingof records, resultingin dis-

gation also involveda degree of self-criticism:I, tinctionsbetween form (technology)and content

likeotherscholars,had overlookedpassing refer- (programming) thattoday seem misguided.

ences to the developmentof Germantelevisionin Butthe post-wardivisionof the Germannation

already examined sources such as the trade pa- exacerbated this tripartdivision, posing further

pers Lichtbild-Buhne and Der Kinematograph.I problemsfor the researcher.An archival record

realized that the aleatory nature of archival re- already affected by war-timeloss and destruction

search sometimes gave rise to surprising dis- was splitbetween the east and west, leavingeach

coveries but perhaps more often concealed yet side with partialbut ideologically advantageous

moreinterestingones. Furtherlessonsawaited as I documentation.Inthewest, the Bundesarchiv's col-

pursuedthe topic. lection of propaganda ministryrecords encour-

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

258

258 William

William Uricchio

Uricchio

aged examinationof theway thatthe Nazi's televi- the Germanarchivalholdingsare far more useful

sion programminghad functionedwithin a top- than those at the BritishPublic RecordsOffice,

down political party structuredependent upon where the records which deal with Britishintel-

'injecting'fascistideology intothoseat the bottom, ligence awareness (if any) of German television

an interpretation that contributedto the 'Hitleras remainclassified.Yeteven the PublicRecordsOf-

madman' historiographicalexplanation that ab- fice seems forthcomingby contrastwith the stone-

solved the mass of the German people from re- walling treatmentaccorded scholars by the US

sponsibility for Nazi outrages. In the east, the companies, IT&T and RCA,that continuedto co-

German Democratic Republic (GDR) State operate withthe Reichin thedevelopmentof televi-

Archive,inheritorof the post ministryrecordson sion throughout the war. The trans-national

technology,held evidence thatshowed active col- technologicalevolutionof the televisionapparatus

laborationbetween the German Reichand multi- makesthe roleof US-basedmulti-national corpora-

national electronicscorporations,contributingto tions in the developmentof Germantelevisionless

the 'fascism as capitalism run amok' historio- thansurprising,butactive collaborationin the de-

graphicalexplanationthatlinkedthecurrentrulers velopmentof television-basedguidance systems

of West Germanyto the Nazi past2. for rockets,bombsand torpedoes,or in the manu-

Archivalaccess problemsadded to those al- factureof such militaryhardwareas fighterair-

readyarisingfromdocumentdistribution and ideo- craft, seems more transgressive.Fortunately,the

logical agendas. Some record collections in the GDR archivists preserved the relevant German

west, such as the US-runBerlinDocumentCentre, holdingson thisinvolvement,butcheckingthatdo-

were only selectively accessible to east or west cumentationfromthe US perspectivehas been far

Germanresearchers;othersin theeast, suchas the moredifficult.Thecorporations,with littleto gain

StateArchive,provedextremelyreluctantto make fromsuchhistoricalresearch,have not been eager

recordsavailable that hadn'tfirstbeen screened to open theirarchives.Butthe ever-vigilanteyes of

by local experts. Restrictionsin both cases often the Hoover-FBI provideat least some sense of the

entailed requestsfor specific information,such as USgovernment'slevelof interestin and awareness

the name and birthdateof the sender, the date, of corporate activities. In the case of IT&T,for

and the contentsof the documentone wished to example, a secret congressional sub-committee

inspect,a procedurethat preventedthe fortuitous authorizeda long termFBItap on chairmanof the

discoveries so crucial to historicalresearch.The board Sosthenes Behn's telephone and do-

GermanReich'sinitialtri-partdivisionof responsi- cumentedthe extent of his corporation'sinvolve-

bilityfor the medium,togetherwiththe partialna- mentwiththe Reich.Yetwhile evidence had been

tureof the east and west's archivalholdingsand collected, scholarscould not necessarilyaccess it,

the pointedlyideological uses to which these rec- since the strategicvalue of IT&T's holdingsin cen-

ords had been put, contributedto the disappear- tralEuropeto a cold-warobsessed US government

ance of the historyof earlyGermantelevisionfrom resultedin the suppressionof the materialgathered

collectivememory. duringthe finalyears of the war. Freedomof Infor-

Despite these and related problems, re- mation Act appeals to the FBInotwithstanding,

searchersof the NS period tend to be aware of Behn'stelephone transcriptsremainunavailable,

theirprivilegedpositionvis-a-viscolleagues work- and other material regarding the corporation's

ing in US, British,or Soviet historyof the same German activities during the war are available

period. Germany'sdefeat resultedin de facto de- only in heavily censored form. The National

classification,as the victors,togetherwiththe new Archives,repositoryfor, among other things, the

regimes, seized, copied, preserved and made original congressional investigating committee

available,albeitin limitedfashion,the relevantdo- files, was more responsiveto appeals for the de-

cuments.Butwhile usingGermansourcesto docu- classificationof the relevantrecords,so that in the

ment the history of German television proves end, muchof the materialconsideredoff-limitsby

promising,pursuingthe search beyond German the FBI(includingthe transcripts)can be found in

archives proves more problematic.Forexample, anotherfederalagency3.Atleast inthisinstanceof

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Archives and absences

Archives and absences 259

259

governmentalresponsibilityfor the archival rec- prioritizefilmsforpreservationand henceto shape

ord, inefficiency and duplication have had a the access of futuregenerationsto the cinema past

tremendousadvantage. The larger point, how- emerge froman historicallyspecific configuration

ever, is that archivalpolicy can be responsiveto of the fieldof filmstudies.

the interestsof the state, and thatnationalinterests Many of the people responsiblefor archival

can be mobilized to mask and delimit the re- preservationpolicy,likemanyof the readersof this

searcher'saccess to the existinghistoricalrecord. journal,were intellectuallyshaped duringthe for-

Hence, the littlethat has been writtento date on mativeyears of cinema studiesas a universitydis-

earlyGermantelevisionis shaped by the ideologi- cipline.Theinstitutional apparatusfor 'filmas art',

cal contextof the GermanReich,the post-wardivi- so centralto the legitimacysought by proponents

sion of the nation,the cold war and multi-national of filmstudies(and theiruniversityadministrators)

capitalism. includedthe auteurtheory,art museum-sponsored

screeningsof experimentalfilms,and the revival

and expansion of the art house circuit.Although

Structuralabsences

specialistsmaywell be struckby the field'sremark-

Restrictions and censorshipoffer particularlyvex- able intellectualgrowth,these formativeperspec-

ing barriersto archiveusers, but the presumption tives and assumptionsof some thirtyyears ago

that the offending documentsactually exist and remaincentral to archivists'policies. Distinctin-

may some day be considered sufficientlyinno- stitutionalincentivescontributeto maintaininga re-

cuous to be made available still remains.More- strictiveand outmodedconceptionof 'filmas art'.

over, the ever-presentpossibilitythatthe material Some US filmprogrammesearn theirkeep by pro-

censored by one agency (or individual,for in the vidingcourseswhichfulfilartsrequirements, while

end appeals are decided by particularagents), severalmajorfilmarchivesjustifytheirbudgetsby

may be made available by another encourages strategicalliancewiththe traditionalelite arts. But

persistence as a particularly useful research the interrogationof canons and taste hierarchies

strategy.Butin the case of archivalfilmand televi- mountedby proponentsof culturalstudies reveal

sion holdings, the budgetary restrictions that that an emphasis upon 'filmas art' may in many

necessitatethe selectivepreservationof some texts instancesprecludean emphasisupon 'filmas cul-

and the de facto destructionof othershave rather ture', since the texts necessary for the latterap-

more permanentand irrevocableconsequences. proachmay be excludedby archivalpreservation

Althoughthe basic problemsof preservingthe two policies.

media are roughlythe same, filmis actuallyin a Irecentlyasked mystudentswhichtheatrically

muchbetter positionthan television.The relative screened filmin the Netherlandshad the greatest

durabilityof celluloid,film'slongerinstitutionalhis- numberof viewersthisyear. Theanswerto thistrick

its

tory(including place in museums, archives and questionwasn't Schindler'sListor JurassicPark,

the academy), and its aestheticstatus,all contrib- butany one of a numberof pre-featurefilmadver-

ute to a higher preservationprofilethan that ac- tisementsforGrolschor Heinekenor Camels,texts

corded television.So let's look at the limitsof this seen on average by fiveor six timesthe numbersof

'bestcase' preservationscenario. viewers of the biggest drawingfeatures.Many of

Inthecase of bothfilmand television,farmore these advertisementsare quite engaging, some

materialshould be preservedthan can be. Most pushingthe limitsof narrativeor representationbe-

filmarchiveswith active restorationand preserva- yond thatseen in 'typical'feature.As textsin their

tionprogrammeshave developeda reasonablyar- own right,as culturalobjects,and as centralcom-

ticulateset of prioritiesto distinguishbetween the ponentsin constructingthe conditionsof reception

filmswhich will surviveand those which will be forthe filmsthatfollow, these advertisementshave

abandoned, with organizationssuch as FIAFen- tremendousimportance.Butthey seem to be as

couraging open communicationamong different invisible to many archivists, given their tunnel-

archivesto minimizedisaster.Yet, at least in the vision of 'filmas art', as they are to my students.

case of many film archives, the criteriaused to The marginalizationof 'ordinary'industrials,in-

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

260

260 William Uricchio

William Uricchio

structionals,advertisingfilms,and so forth,seems using non-cinematichistoricalsources in an effort

short-sightedeven withinan aestheticframework. to locate filmand televisionwithinthe culturalhis-

Ifthe 1 1thcentury'sdevotionalobjectsare the art toryof our century.Thefirstproblemis thatof the

treasuresof today, who can predictwhetheror not historicalfiltrationof evidence, a processby which

the late 20th century'sadvertisingwill be the art the archival selection criteria determined by a

treasuresof the future? period'sdominantsocial formationsshape and de-

Such marginalizationseems even moreshort- limitour access to the past. Evidencerelated to

sighted from the perspectiveof culturalhistory. marginalizedsocial formationsis oftensimplymis-

Archivalacquisitionpolicies mustbecome respon- sing fromthe historicalrecordsince period archi-

sive to 'the filmas culture'ratherthan the 'filmas vists deemed it unworthyof preservation.On the

art'paradigm,meaningthatarchivistsmustbegin other hand, a plethoraof readily available evi-

to takea longerand broaderview insteadof being dence entails a similarbut related problemcon-

attuned to the aesthetic norms of a particular cerning the researcher's historiographic

period. But because the expansionist years of assumptions. A fixation with readily available

manyfilmarchivescoincided with such factorsas 'facts'can obscurethecomplexitiesand contradic-

the deploymentof the legitimizingdiscourseof film tionswhich help to constructa historicalmoment,

of universitycinema

as art, the institutionalization privileging'dead certainties'over the ambiguities

studies programmes,and the trainingof a new of competingdiscourses.

generation of film archivists,the perceived com- In order to develop these points a bit more

mon interestsof archivistsand scholarshas grown fully, I would like to discuss two related projects

uncommonlyclose. Historicallyspecific notionsof that RobertaPearsonand I have worked on: the

an academic field ('filmas art'), reinforcedby in- firstconcernsthe conditionsof receptionfor par-

stitutionalconstraintsand the personalinvestments ticularfilmsand the second theculturalcontroversy

of those involved, has spilled over into archival over cinema theatresin New YorkCity between

preservationpolicy. 1907 and 19134. Thefirstproject,a book on the

Inthis regard, a latenttensionunderlyingthe VitagraphCompany'sliterary,historicaland bibli-

relationship of archivists and academic re- cal 'qualityfilms',looked at the filmindustry'suse

searchers might help us get beyond the familiar of such culturallyprominentfigures as Shakes-

debate between preservationvs use. We might peare, Washington, Napoleon and Moses in an

productivelyenhancethe tensionbetweenpreserv- effortto attain culturalrespectability.The book,

ing materialforthe researchquestionsof the future concerned not only with a 'top-down'analysis of

vs the researchagenda of the immediatepresent. the film-industry,butwitha 'bottom-up'analysisof

Such an effort might ironicallycontributea wel- the probableresponsesof workingclass and immi-

come dimensionto the traditionalantagonismbe- grant viewers, falls broadlywithinthe social his-

tween the interestsof archivistsand researchers, toryso muchin evidence since the Second World

serving the interestsof futuregenerations of re- War. As with many such projects, perhaps the

searchers. Butwhile so much of the filmed past greatestresearchdifficultystemsfromthe tendency

remainsat risk,we can only hope that the diver- of manyarchivesto collect materialrelatedto the

gent views of researchersand archivistscan be dominantsocial formationswhile ignoring more

productivelycultivatedand deployed in a com- marginalgroups. And while findingcopies of the

bined preservationeffort. Police Gazette, the nineteenthcenturyequivalent

of The National Enquirer,may be much harder

thanfindingcopies of the New YorkTimes,obtain-

The problems of historical filtration

ing evidence perhaps moredirectlyrelatedto the

While we mightcontest the existing preservation experiencesof immigrantand workingpeople of

criteriaof filmand televisionarchives,at least the the period poses an even moredifficultchallenge.

termsare now and have been in the past reason- The collectionsavailable at the New YorkPublic

ablyclear- generallywe knowwhatto expect. Far Library,the New-YorkHistoricalSociety, YIVO,

more complex archival challenges face scholars and the Libraryof Congressare testamentsto the

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and absences

Archivesand

Archives absences 261

261

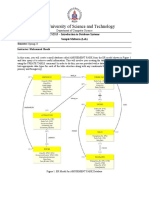

Fig.2. ThePrincessTheatre,anglingforan upscaleaudienceby programmingGrenadierRolandand

TheFallof Troy(191 1). [Courtesyof Q. DavidBowers.]

'bestand brightest'of the period,butfortheexperi- search approach) by a creative use of non-cine-

ences of 'ordinary'people, one mustlookeitherto matic sources at certain archivalcollections. De-

social surveystudiesor to morerecentlyobtained ciding thatwidely circulatingdepictionsof figures

oral histories.Ineithercase, the materialobtained such as Washingtonor Moses, or greatly simpli-

mustbe verycarefullyconsidered,for it is far more fiedversionsof Shakespeare'sJulius Caesaror Na-

mediated(eitherby a social science paradigmor poleon's career all helped to establish the

by the ravages of time)than the sortsof material intertextual frame to which many 'ordinary'

availablewhen consideringthe conditionsof cine- viewers would have been exposed, we found

maticrepresentationfor representativesof the 'bet- treasuretrovesof popularimageryin sucharchives

ter'classes. as the ArentsTobacco collectionat the New York

The difficultiesof historicalfiltrationcan to Public Library(with cigarette cards and cigar

some extent be offset (depending upon one's re- labels) or the BurdickCollectionat the Metropoli-

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262

262 William

William Uricchio

Uricchio

tan Museumof Art (withadvertisingand packa- tionsof the new movingpicturemediumprovesfar

ging materials),or the Bella C. LandauerCollec- more profitable than searching for definitive

tion at the New-York Historical Society (with 'facts'.Iwouldargue thatthe portrayalsof moving

writingtablets and calendars).Thisextrapolated pictureexhibitionoriginatingfromthe press and

intertextualframe, reinforcedby such sources as pulpithad far greaterimportthan the numbersor

school text books and classroom chromolitho- even locationsof theactualtheatres.Indeed,if one

graphs, churchsermons,public statuary,parade wishes to understandthe mobilizationof public

floats, and public lectures, led to historically- sentiment,the passing of legislation,and the film

groundedspeculationsabout the probablecondi- industry'sresponses, the period'sown depictions

tions of reception for Vitagraph's films among tell us morethan a futileattemptto reconstructan

working class and immigrantaudiences which historical'reality'.Of course, some sense of 'em-

contrastedsharplybothwith our presentistexpec- pirical reality' provides a necessary reference

tationsand withdominantperiodsources.Ininter- pointby whichwe can appraise pressreportsand

rogatingcontemporaryconditionsof receptionwe othersuchdata, butdocumentingperceptionsgets

had in some respectsto 'create'ourown evidence, us far closer to understandingthe implementation

butwiththe New YorkCitynickelodeonprojectwe of culturalpolicy. We shouldcarefullyinterrogate

faced a potentiallyoverwhelmingarrayof 'facts'. competingdiscourses,retaininga high tolerance

Intentupon understandingthe social/culturalposi- for ambiguity, ratherthan search for more and

tion of New York'snickelodeons,we attempted, more'facts'thatmightresultin a monolithicinter-

like several previous scholars, to determinethe pretation.

numberand locations of moving pictureshows.

Locating previously untapped material in New

YorkCity'sMunicipalArchives,we foundthatoffi- Conclusion

cial city sourcesvarieddramaticallyin theircounts Thedemandsof the new culturalhistoryencourage

of the city's movingpictureshows. New Yorkhad a farmorecreativeuse of archivalsourcesthanhas

upto seven departmentsinvolvedinsomeaspect of hithertobeen the case. Whether reading docu-

exhibitionregulation,yet in 1908, the Department ments against the grain, or finding alternative

of Policecounted239 nickelodeons,the Bureauof sourcesof documentation,or of 'reading'the very

Licences,550, and the Departmentof Buildings, process of archiving (a la Foucault6),strategies

800. Recourseto otherarchives,suchas thepaper- exist to circumventthe originating 'intention'of

s of the civic reformorganization,the People'sIn- previousgenerationsof archivists.Butin conclud-

stitute,located at the New YorkPublicLibrary,led ing I wish to returnto my most importantpoint. I

to still more 'facts', such as those of a People's take the inevitablecurse of 'presentism'far more

Institute report on 'cheap amusements' that seriouslyin the case of filmarchives,where it has

countedover 400 nickelodeons.Clearly,city offi- an irrevocablecharacter,than in the case of other

cials and reformershad politicalagendas which archives, where it serves as a stimulantto more

inflectedtheir'facts', butthe extentof the discrep- creative researchstrategies.The difficultiesto re-

ancy is striking.The situation is furthercompli- searchers,presentand future,posed by the aesthe-

cated, since manyof the moretransient,tenement tically oriented preservationcriteriaof most film

district nickelodeons were not recorded in the archivesfacing archivalcollectionsof filmsare far

more official sources such as Trow'sBusinessDi- less negotiable than those posed by problemsof

rectorybut ratheronly fortuitously enteredthe his- historicalfiltration.Those films lost because they

torical record through newspaper reports of don't conformto presentistaesthetic criteriawill

nickelodeondisastersor police shut-downsof mov- constitutea significantabsence for the future.And

ing pictureshows. althoughfutureresearchersmaywell have an easy

The 'incompleteness' of this particularevi- time appraisingour archivalvalues and assump-

dence base need not necessarilyrestricthistorical tions,theywillhavean extraordinarily difficulttime

interpretation,since considering discursive evi- conjuringup films that no longer exist. Despite

dence concerningthe period's dominantpercep- some strategicadvantages in maintaininga level

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Archivesand absences 263

of tension between archivists and researchers on systematicepisodesof documentlosswhensearch-

the needs of the future vs the needs of the present, ing for IT&T-related recordsin the State Depart-

mentsarchives.Inthesecases, the recordentrylog

there may be a longer term advantage to closer

indicates the existence of documentswhich the

cooperation at least with regard to the questions archivistshave been unableto locate, and in the

raised by new developments in cultural history. case of the ITTrelatedrecordsIsought,over70 per

One can easily criticize any selection process with centof the entereddocumentswere missing.

such irrevocable consequences, and my point here 4. Thefirstpartof this research,whichconsidersthe

is not to single out archival policy-makers as some- conditionsof productionand receptionfor particu-

how conspiring to impose a particularform on film larfilms,appearsas Reframing Culture:Thecase of

the VitagraphQualityFilms(PrincetonUniversity

history, but perhaps thinking more about the pro-

cess and implications of constructing history, and Press,1993): the secondpart,whichconsidersthe

debateover motionpictureexhibitionin New York

less about defending a presentist notion of 'aes-

City, is forthcomingas TheNickelMadness:The

thetics,' will encourage more far-sighted archival Struggleto ControlNew YorkCity'sNickelodeons

policies. in 1907-1913 (Smithsonian Institution

Press).

5. ResearchersfromRussellMerrittand RobertAllen

Notes (who challengedthe then dominantview thatnic-

kelodeonaudienceswere primarilyworkingclass

1. Recentexpressionsof these issuesmaybe foundin and immigrant) to BenSinger(whohas embarked

theworkof HaydenWhiteand DominickLaCapra, on an ambitiouslocationanalysisof NY nickelo-

or in collectionsof essays suchas AramVeeser's deons) have contributedto this quest.See Russell

The New Historicismand LynnHunt'sThe New Merritt,'NickelodeonTheaters,1905-1914: Build-

CulturalHistory(Berkeley:Universityof California ingan AudiencefortheMovies',inTinoBalio,(ed.),

Press, 1989). TheAmericanFilmIndustry, Universityof Wisconsin

Press, Madison,Wisconsin, 1976, pp. 831102;

2. Fora lookat the researchspawnedby thesediffer- RobertAllen,'MotionPictureExhibition inManhat-

ent archivalsourcessee WilliamUricchio,Die An- tan, 1906-1912: Beyondthe Nickelodeon'inJohn

fange des Deutschen Fernsehens: Kritische Fell,(ed.),FilmBeforeGriffith,Universityof Califor-

Annaherungenan die Entwicklung bis 1945 (Tub- nia Press, Berkeley,California,1983, pp. 162-

ingen:NiemeyerVerlag,1991). Foran overviewof 175; and Ben Singer, 'ManhattanNickelodeons:

theresearchand itsideologicalimplications,see my New Data on Audiencesand Exhibitors', Cinema

'Televisionas History:Representations of German Journal (forthcoming). Fora senseof ourapproach

TelevisionBroadcasting,1935-1944', pp. 167- to the issue, see WilliamUricchioand RobertaE.

196 in Framingthe Past:The Historiography of Pearson,'Constructing the Audience:Competing

GermanCinemaand Television,edited by Bruce Discoursesof Moralityand Rationalization in the

Murrayand ChristopherWickham(Carbondale: NickelodeonPeriod',Iris17, 1994, 43-54 .

SouthernIllinoisUniversityPress,1992).

6. MichelFoucault,TheArchaeologyof Knowledge

3. Thisis not to implythatall of my declassification and the Discourseon Language,(New York:Pan-

requestsat the NationalArchiveshavemetwiththe theon, 1972).

samesuccess.Moreover,certaincollectionsseemto

have been purged,or at least I have encountered

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.152 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 01:02:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- What's in the Past: Symbols, Rituals and Folkloric Imagery in Historical-Comparative PerspectiveFrom EverandWhat's in the Past: Symbols, Rituals and Folkloric Imagery in Historical-Comparative PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Paul Smith - The Historian and Film-Cambridge University Press (1976) PDFDocument216 pagesPaul Smith - The Historian and Film-Cambridge University Press (1976) PDFAlexandre BrasilNo ratings yet

- Black History - White History: Britain's Historical Programme between Windrush and WilberforceFrom EverandBlack History - White History: Britain's Historical Programme between Windrush and WilberforceNo ratings yet

- SturkenDocument11 pagesSturkenanjitagrrNo ratings yet

- A Very Long EngagementDocument13 pagesA Very Long EngagementSalome TsopurashviliNo ratings yet

- Film 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureFrom EverandFilm 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureAnnemone LigensaNo ratings yet

- Project Muse 222330Document13 pagesProject Muse 222330Anonymous SK0Xx9wvKNo ratings yet

- The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema: North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920sFrom EverandThe Institutionalization of Educational Cinema: North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920sNo ratings yet

- Izod and Kilborn-Redefining CinemaDocument5 pagesIzod and Kilborn-Redefining CinemaAlexa HuangNo ratings yet

- Serializing Age: Aging and Old Age in TV SeriesFrom EverandSerializing Age: Aging and Old Age in TV SeriesMaricel Oró-PiquerasNo ratings yet

- Musser (1984) Toward A History of Screen PracticeDocument12 pagesMusser (1984) Toward A History of Screen PracticeStanleyNo ratings yet

- Ethnographic Film: Failure and PromiseDocument22 pagesEthnographic Film: Failure and PromiseChristina AushanaNo ratings yet

- The World As Object LessonDocument24 pagesThe World As Object LessontoddlertoddyNo ratings yet

- The Role of Orphan FilmsDocument6 pagesThe Role of Orphan FilmsCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Does Film History Need A Crisis?Document6 pagesDoes Film History Need A Crisis?Dimitrios LatsisNo ratings yet

- World of MusicDocument19 pagesWorld of MusicnpoulakiNo ratings yet

- Elsaesser-Writing Rewriting Film HistoryDocument12 pagesElsaesser-Writing Rewriting Film Historyalloni1No ratings yet

- Vincent HistoryDocument34 pagesVincent HistoryWanLan1990No ratings yet

- Grey Room, Inc. and The Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyDocument23 pagesGrey Room, Inc. and The Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyruralhyphenNo ratings yet

- Film and History: A Very Long Engagement - Gianluca FantoniDocument23 pagesFilm and History: A Very Long Engagement - Gianluca Fantonidanielson3336888100% (1)

- History, Cinema's Auxiliary - LagnyDocument13 pagesHistory, Cinema's Auxiliary - LagnytlenineNo ratings yet

- Zielinski - Cinema and TVDocument357 pagesZielinski - Cinema and TVTylerescoNo ratings yet

- ANDERSON, Steve F. - Found Footage', Technologies of History. Visual Media and The Eccentricity of The Past PDFDocument7 pagesANDERSON, Steve F. - Found Footage', Technologies of History. Visual Media and The Eccentricity of The Past PDFescurridizo20No ratings yet

- What Are The Principal Strengths and Wea PDFDocument23 pagesWhat Are The Principal Strengths and Wea PDFАлена ХитрукNo ratings yet

- Screen 2014 Uricchio 119 27Document9 pagesScreen 2014 Uricchio 119 27NazishTazeemNo ratings yet

- Science and Islam - ReviewDocument3 pagesScience and Islam - ReviewAzul, John Eric D.No ratings yet

- Siegfried Zielinski Deep-Time-Of-The Media Intro ConclusionDocument149 pagesSiegfried Zielinski Deep-Time-Of-The Media Intro ConclusionRegilene SarziNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 118.71.190.165 On Tue, 16 Aug 2022 15:28:38 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 118.71.190.165 On Tue, 16 Aug 2022 15:28:38 UTCseconbbNo ratings yet

- História Dos Arquivos ModernosDocument8 pagesHistória Dos Arquivos ModernosFelipe MamoneNo ratings yet

- Elsaesser - Film Studies in Search of The ObjectDocument6 pagesElsaesser - Film Studies in Search of The ObjectEmil ZatopekNo ratings yet

- The Cinema of Economic MiraclesDocument222 pagesThe Cinema of Economic MiraclesAfece100% (1)

- FOSTER, An Archival ImpulseDocument21 pagesFOSTER, An Archival ImpulseFelipe MamoneNo ratings yet

- Documentary Film Festivals Vol. 1: Methods, History, PoliticsDocument306 pagesDocumentary Film Festivals Vol. 1: Methods, History, PoliticsGemboeng Jr.No ratings yet

- De Gaudio Animated DocumentaryDocument12 pagesDe Gaudio Animated Documentaryazucena mecalcoNo ratings yet

- Carlo Testa - Italian Cinema and Modern European Literatures - 1945-2000 (2002) - 2Document291 pagesCarlo Testa - Italian Cinema and Modern European Literatures - 1945-2000 (2002) - 2shaahin13631363No ratings yet

- Researching Newsreels Local National and Transnational Case Studies 1St Ed Edition Ciara Chambers All ChapterDocument67 pagesResearching Newsreels Local National and Transnational Case Studies 1St Ed Edition Ciara Chambers All Chapterkenneth.bender815100% (10)

- Zielinski, Siegfried - Deep Time of The Media. Toward An Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical MeansDocument391 pagesZielinski, Siegfried - Deep Time of The Media. Toward An Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical MeansNadia_Karina_C_9395No ratings yet

- BELL, Desmond - Found Footage Filmmaking and Popular MemoryDocument16 pagesBELL, Desmond - Found Footage Filmmaking and Popular Memoryescurridizo20No ratings yet

- 6971-Article Text-34238-2-10-20201120Document14 pages6971-Article Text-34238-2-10-20201120João ManuelNo ratings yet

- TV Through The Looking GlassDocument24 pagesTV Through The Looking GlassNick JensenNo ratings yet

- History TV and Popular MemoryDocument16 pagesHistory TV and Popular MemoryfcassinsNo ratings yet

- CAT 2023 Slot 2 Question Paper by CrackuDocument85 pagesCAT 2023 Slot 2 Question Paper by Crackushubhamrathi722No ratings yet

- Jonathan Crary - Géricault, The Panorama, and Sites of Reality in The Early Nineteenth CenturyDocument24 pagesJonathan Crary - Géricault, The Panorama, and Sites of Reality in The Early Nineteenth CenturyLOGAN LEYTONNo ratings yet

- History in Images/History in Words: Reflections On The Possibility of Really Putting History Onto FilmDocument13 pagesHistory in Images/History in Words: Reflections On The Possibility of Really Putting History Onto FilmcjNo ratings yet

- Histories of Film History: About The ConferenceDocument2 pagesHistories of Film History: About The ConferenceMaria Gabriela ColmenaresNo ratings yet

- Documentary History Social MemoryDocument11 pagesDocumentary History Social MemoryDominique JonesNo ratings yet

- Documentary Film Festivals Vol 1 Methods History Politics 1St Ed Edition Aida Vallejo Full ChapterDocument67 pagesDocumentary Film Festivals Vol 1 Methods History Politics 1St Ed Edition Aida Vallejo Full Chapterjennifer.mcculla443100% (8)

- Tom GunningDocument24 pagesTom GunningiroirofilmsNo ratings yet

- La Voz HumanaDocument2 pagesLa Voz HumanaFLAKUBELANo ratings yet

- Louis B. Mayer I:Oundl41'Ion: Library of CongressDocument5 pagesLouis B. Mayer I:Oundl41'Ion: Library of CongresshirschjnNo ratings yet

- Neo-Mythologism Apollo and The Muses On The ScreenDocument42 pagesNeo-Mythologism Apollo and The Muses On The ScreenvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 188.189.112.145 On Sat, 15 May 2021 10:00:50 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 188.189.112.145 On Sat, 15 May 2021 10:00:50 UTCIrene GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Uricchio, W. (2004) Storage, Simultaneity PDFDocument19 pagesUricchio, W. (2004) Storage, Simultaneity PDFpaologranataNo ratings yet

- Film As HistoryDocument32 pagesFilm As HistorykimbuanderssonNo ratings yet

- Catherine Russell - New Media and Film History - Walter Benjamin and The Awakening of CinemaDocument6 pagesCatherine Russell - New Media and Film History - Walter Benjamin and The Awakening of CinemaCristian SintildeNo ratings yet

- 14 From Primitive To ClassicalDocument19 pages14 From Primitive To ClassicalΣταυρούλα ΝουβάκηNo ratings yet

- The Study of Suspense in Science and Education Documentary: An Interpretation Based On Text AnalysisDocument11 pagesThe Study of Suspense in Science and Education Documentary: An Interpretation Based On Text Analysisindex PubNo ratings yet

- 4 - 2 - Gunning - 1997 - Before DocumentaryDocument14 pages4 - 2 - Gunning - 1997 - Before DocumentarySofija ŽadeikytėNo ratings yet

- Robbers Princeton 0181D 10096Document488 pagesRobbers Princeton 0181D 10096Angga Setyawan0% (1)

- Laura Mulvey in Conversation With Griselda PollockDocument13 pagesLaura Mulvey in Conversation With Griselda PollockCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Lectura Opcional Against Digital Art HistoryDocument10 pagesLectura Opcional Against Digital Art HistoryCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Bender. Place and LandscapeDocument11 pagesBender. Place and LandscapeCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- The Role of Orphan FilmsDocument6 pagesThe Role of Orphan FilmsCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Ludwig Wittgenstein Remarks On ColourDocument107 pagesLudwig Wittgenstein Remarks On ColourJennifer Rose100% (5)

- Piil Characteristics ArchivingDocument4 pagesPiil Characteristics ArchivingCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Painting Photography FilmDocument148 pagesPainting Photography FilmÖzge DurmazNo ratings yet

- Deren Maya An Anagram of Ideas On Art Form and FilmDocument27 pagesDeren Maya An Anagram of Ideas On Art Form and FilmWilliam PearsonNo ratings yet

- 50Document5 pages50Pedro Ivan100% (1)

- Sample Midterm (Lab)Document3 pagesSample Midterm (Lab)Shahab designerNo ratings yet

- 7.2kV Current Transformer - WH3Document2 pages7.2kV Current Transformer - WH3Sandhi YudiyantoNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Instructions For Voltage Detecting SystemDocument1 pageMaintenance Instructions For Voltage Detecting Systemيوسف خضر النسورNo ratings yet

- Carrier AggregationDocument40 pagesCarrier Aggregationmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Construction Planning and SchedulingDocument70 pagesConstruction Planning and SchedulingDessalegn AyenewNo ratings yet

- SparqugDocument48 pagesSparqugIan BagleyNo ratings yet

- M580 HSBY System Planning GuideDocument217 pagesM580 HSBY System Planning GuideISLAMIC LECTURESNo ratings yet

- 4150 70-37-3 Requirement AnalysisDocument71 pages4150 70-37-3 Requirement AnalysisSreenath SreeNo ratings yet

- Linkedin Emerging Jobs Report Indonesia FinalDocument24 pagesLinkedin Emerging Jobs Report Indonesia Finallontong4925No ratings yet

- Supercars Final Newcastle Destination Management Plan June 19 2013Document59 pagesSupercars Final Newcastle Destination Management Plan June 19 2013api-692698304No ratings yet

- TW Ebook Product Thinking Playbook Digital2pdfDocument172 pagesTW Ebook Product Thinking Playbook Digital2pdfgermtsNo ratings yet

- New Gen Trunnion Soft Seat Ball ValveDocument7 pagesNew Gen Trunnion Soft Seat Ball ValvedirtylsuNo ratings yet

- SGV Series: Storage Filling PumpDocument2 pagesSGV Series: Storage Filling PumpAnupam MehraNo ratings yet

- B-0018-1-Al Khayal Gen. Cont. (Hordi Block) (Comp. Strength)Document1 pageB-0018-1-Al Khayal Gen. Cont. (Hordi Block) (Comp. Strength)Matrix LaboratoryNo ratings yet

- Lab 521Document8 pagesLab 521Shashitharan PonnambalanNo ratings yet

- BiyDaalt2+OpenMP - Ipynb - ColaboratoryDocument3 pagesBiyDaalt2+OpenMP - Ipynb - ColaboratoryAngarag G.No ratings yet

- Schengen Visa Application 2021-11-26Document5 pagesSchengen Visa Application 2021-11-26Edivaldo NehoneNo ratings yet

- تقارير مختبر محركات احتراق داخليDocument19 pagesتقارير مختبر محركات احتراق داخليwesamNo ratings yet

- Arduino Nano DHT11 Temperature and Humidity VisualDocument12 pagesArduino Nano DHT11 Temperature and Humidity Visualpower systemNo ratings yet

- SM ATF400G-6 - EN - Intern Use OnlyDocument1,767 pagesSM ATF400G-6 - EN - Intern Use OnlyReinaldo Zorrilla88% (8)

- IsoMetrix Case Study OmniaDocument9 pagesIsoMetrix Case Study OmniaOvaisNo ratings yet

- National University: Syllabus Subject: MathematicsDocument3 pagesNational University: Syllabus Subject: MathematicsFathmaakter JuiNo ratings yet

- OpenTaps in RetailDocument13 pagesOpenTaps in RetailtarunsainaniNo ratings yet

- Meridium Enterprise APM ModulesAndFeaturesDeploymentDocument517 pagesMeridium Enterprise APM ModulesAndFeaturesDeploymenthellypurwantoNo ratings yet

- Principles of Electric Circuits - FloydDocument40 pagesPrinciples of Electric Circuits - FloydhdjskhdkjsNo ratings yet

- Marketing Manager: at Aztec GroupDocument2 pagesMarketing Manager: at Aztec GroupAgnish GhatakNo ratings yet

- Rodavigo Acoplamientos 02 Acoplamientos de BielasDocument20 pagesRodavigo Acoplamientos 02 Acoplamientos de BielasArturo J. Londono MNo ratings yet

- PLDT Application Form-1Document2 pagesPLDT Application Form-1juanita laureanoNo ratings yet

- DRV 33Document38 pagesDRV 33Alpha ConsultantsNo ratings yet

- Colleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListFrom EverandColleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListNo ratings yet

- David Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderFrom EverandDavid Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderNo ratings yet

- English Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreFrom EverandEnglish Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Jack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesFrom EverandJack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Christian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesFrom EverandChristian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- 71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Myanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionFrom EverandMyanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionNo ratings yet

- Seven Steps to Great LeadershipFrom EverandSeven Steps to Great LeadershipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Bibliography on the Fatigue of Materials, Components and Structures: Volume 4From EverandBibliography on the Fatigue of Materials, Components and Structures: Volume 4No ratings yet

- Help! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyFrom EverandHelp! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyNo ratings yet

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Patricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideFrom EverandPatricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- 71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Sources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksFrom EverandSources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksNo ratings yet

- Seeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksFrom EverandSeeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksNo ratings yet

- Political Science for Kids - Democracy, Communism & Socialism | Politics for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandPolitical Science for Kids - Democracy, Communism & Socialism | Politics for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- American Founding Fathers In Color: Adams, Washington, Jefferson and OthersFrom EverandAmerican Founding Fathers In Color: Adams, Washington, Jefferson and OthersNo ratings yet

- Chronology for Kids - Understanding Time and Timelines | Timelines for Kids | 3rd Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandChronology for Kids - Understanding Time and Timelines | Timelines for Kids | 3rd Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- My Mini Concert - Musical Instruments for Kids - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical InstrumentsFrom EverandMy Mini Concert - Musical Instruments for Kids - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical InstrumentsNo ratings yet

- The Pianist's Bookshelf, Second Edition: A Practical Guide to Books, Videos, and Other ResourcesFrom EverandThe Pianist's Bookshelf, Second Edition: A Practical Guide to Books, Videos, and Other ResourcesNo ratings yet