Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eric Hobsbawm, Pierre Bourdieu

Uploaded by

Mannoel MottaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eric Hobsbawm, Pierre Bourdieu

Uploaded by

Mannoel MottaCopyright:

Available Formats

NLR 101, September–October 2016

ERIC HOBSBAWM

P I E R RE BOURD I E U

L

et me start with a little story about intellectual ex-

change, which Bourdieu would have liked.1 As we

know, Wittgenstein entirely changed the orientation

of his philosophy after 1929, principally as a result

of the criticisms of the Italian economist Piero Sraffa, with

whom he liked to walk and talk at Trinity College, Cambridge.

One day, when Wittgenstein was putting forth the argument

that a proposition and what it describes must have the same

‘logical multiplicity’, Sraffa replied with a Neapolitan gesture

of scepticism or contempt, brushing his fingertips up and out-

ward from his chin: ‘What is the logical form of this?’ Clearly,

these conversations were of the highest importance for

Wittgenstein, who said he owed to Sraffa an ‘anthropological

method’ of tackling philosophical problems; in other words,

the realization that social rules and conventions contribute to

the sense of our words and gestures.

As for Sraffa, he was far from according the same importance

to his exchanges with Wittgenstein, as he told his friend and

student Amartya Sen (also a friend of Bourdieu).2 In his view,

the argument he had used that day was ‘rather obvious’.

Perhaps, but it was only obvious for someone already ac-

quainted with the ‘anthropological’ approach to philosophy

practiced in the intellectual circles of the Italian left in which

Sraffa was active, and where he had got to know Antonio

Gramsci, a close friend from the days of Ordine Nuovo until his

death. If I start with this story, it is not just because Gramsci’s

preoccupations overlapped to such a large extent with those of

Bourdieu, albeit in a rather different way and in an Italian in-

tellectual context, not a French one; it’s also because it illus-

trates the cultural subjectivity inherent in all intellectual ex-

change. When we read an author, we set off in search of our

own points of interest, not theirs. Thus when non-French histo-

rians read Bourdieu’s work—which flows to such an enormous

extent from his intellectual context, that of post-war France—

it’s not his thought and its development they’re considering,

but their own. Not that it’s a dialogue of the deaf—I think I un-

derstand what Bourdieu is saying—but rather a case of parallel

soliloquies, which sometimes seem to coincide. I would ask

you to bear this in mind if my reading of Bourdieu seems par-

tial or unfounded.

In the light of this initial warning, I will pose a simple ques-

tion: what has Bourdieu contributed, and what can he contrib-

ute, to the work of contemporary historians? What’s most

striking, to begin with, is the central place his work accords to

both history and interdisciplinarity. In the hundredth issue of

Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, a special number that

Bourdieu saw as ‘the reaffirmation of a project’, five of the nine

articles are by historians or devoted to historical subjects; and

six, we may note in passing, are by foreign authors. Indeed, a

quick glance at the journal confirms that in Bourdieu’s last

decade, the Actes turned increasingly towards historical en-

quiry. Bourdieu had been accustomed to working with histori-

ans ever since Braudel had welcomed him to his Maison des

Sciences de l’Homme; in a us-German survey, he is cited

alongside Edward Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Peter Laslett

and Maurice Godelier in a list of contemporary French and

English historians, Marxist or otherwise, with an interest in an-

thropology.3 He took part in Clemens Heller’s fascinating inter-

national gatherings, the Round Tables on Social History, and

published a commentary on our debate on the history of

strikes.4 I vividly recall our conversations in the late seventies

on the need for a history of sport—a topic as dear to the edito-

rial committee of the Actes de la recherche as to Bourdieu him-

self. In short, Bourdieu was perfectly at ease with historians, or

at least with some of them.

And yet, he chose to become not a historian but a philosopher-

turned-sociologist. In his most important writings, he refers

much less to historians than to philosophers, ethnographers

and social anthropologists, and cites even fewer—Georges

Duby, almost alone among his French contemporaries. There

are eminent historians whose names are never mentioned, and

Michelet is specifically rejected. Readers of Homo Academicus

(1984) know how he distrusted the sort of history practiced at

the higher levels of the French system. Despite his gratitude to

Braudel, whose support was unqualified, he had no sympathy

for the longue durée approach of the Annales historians.5 He of-

ten noted their lack of interest in a historical analysis of the

concepts used in the analysis of the past, in a ‘reflexive use of

history’.6 The reproach is not entirely just, especially to the

Germans—one thinks of the encyclopaedic Geschichtliche

Grundbegriffe—but it is true that historians, apart from histori-

ans of ideas, show little interest in philosophy. Nor do philoso-

phers practice much history. In this respect, Hume in the eigh-

teenth century, and Croce and his school in the twentieth, are

the exceptions that prove the rule, though their historical

works are not much read today.

Nevertheless, the past has a central stake in Bourdieu’s work

since it constitutes the soil in which the present’s roots are

plunged, forming the basis for our capacity to understand our

own times and to act upon them. For my own part, like many

historians, I have always admired Bourdieu and have often

been inspired by him. Had he wanted, he could have been a

great historian himself, which is manifestly not the case with

Foucault, Althusser or Derrida, to mention only the French

thinkers best known abroad. Bourdieu had the historian’s pas-

sion for the concrete, the specific, the singular; he had curiosity

and a gift for observing things from a distance—a capability

that good anthropologists share with good historians. Braudel

liked to say: ‘Historians are never on holiday. Each time I take

a train, I learn something.’ Bourdieu would have agreed. Only

someone with a natural gift for social history could have dis-

cerned this characteristic of rural society:

The relative frequency of proverbs, prohibitions, sayings and

regulated rites declines as one moves from practices tied to

agricultural activity, or directly associated with it, . . . towards

the divisions of the day, or moments of human life, not to

speak of domains apparently abandoned to chance, such as the

internal organization of the household, parts of the body,

colours or animals.7

As an observer he was both sensitive to and fascinated by all

that went on below the surface of daily life in his country, the

unspoken and unrecorded assumptions of contemporary

French existence, the symptoms of the nation’s state of health.

Subscribe for instant access to all articles since 1960

Buy the print issue (with instant online access) for £8

Buy this article for £3

Shouldn't I have access to this article via my library?

You might also like

- The Engaged Historian: Perspectives on the Intersections of Politics, Activism and the Historical ProfessionFrom EverandThe Engaged Historian: Perspectives on the Intersections of Politics, Activism and the Historical ProfessionNo ratings yet

- Pierre Bourdieu's Contributions to Critical Sociology and Social HistoryDocument11 pagesPierre Bourdieu's Contributions to Critical Sociology and Social Historyseingeist4609No ratings yet

- The Politics of Majority Nationalism: Framing Peace, Stalemates, and CrisesFrom EverandThe Politics of Majority Nationalism: Framing Peace, Stalemates, and CrisesNo ratings yet

- The Stillbirth of Capital: Enlightenment Writing and Colonial IndiaFrom EverandThe Stillbirth of Capital: Enlightenment Writing and Colonial IndiaNo ratings yet

- Weaving Solidarity: Decolonial Perspectives on Transnational Advocacy of and with the MapucheFrom EverandWeaving Solidarity: Decolonial Perspectives on Transnational Advocacy of and with the MapucheNo ratings yet

- Alsace to the Alsatians?: Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939From EverandAlsace to the Alsatians?: Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939No ratings yet

- Human Rights at Risk: Global Governance, American Power, and the Future of DignityFrom EverandHuman Rights at Risk: Global Governance, American Power, and the Future of DignitySalvador Santino F. RegilmeNo ratings yet

- Sovereign Fantasies: Arthurian Romance and the Making of BritainFrom EverandSovereign Fantasies: Arthurian Romance and the Making of BritainNo ratings yet

- Formative Fictions: Nationalism, Cosmopolitanism, and the BildungsromanFrom EverandFormative Fictions: Nationalism, Cosmopolitanism, and the BildungsromanNo ratings yet

- Richard Rorty: The Making of an American PhilosopherFrom EverandRichard Rorty: The Making of an American PhilosopherRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Global Matters: The Transnational Turn in Literary StudiesFrom EverandGlobal Matters: The Transnational Turn in Literary StudiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Identity and Nationalism in Modern Argentina: Defending the True NationFrom EverandIdentity and Nationalism in Modern Argentina: Defending the True NationNo ratings yet

- BrexLit: The Problem of Englishness in Pre- and Post- Brexit Referendum LiteratureFrom EverandBrexLit: The Problem of Englishness in Pre- and Post- Brexit Referendum LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Participant Observers: Anthropology, Colonial Development, and the Reinvention of Society in BritainFrom EverandParticipant Observers: Anthropology, Colonial Development, and the Reinvention of Society in BritainNo ratings yet

- US public diplomacy in socialist Yugoslavia, 1950–70: Soft culture, cold partnersFrom EverandUS public diplomacy in socialist Yugoslavia, 1950–70: Soft culture, cold partnersNo ratings yet

- Assembling Enclosure: Transformations in the Rural Landscape of Post-Medieval North-East EnglandFrom EverandAssembling Enclosure: Transformations in the Rural Landscape of Post-Medieval North-East EnglandNo ratings yet

- Conservation’s Roots: Managing for Sustainability in Preindustrial Europe, 1100–1800From EverandConservation’s Roots: Managing for Sustainability in Preindustrial Europe, 1100–1800Abigail P. DowlingNo ratings yet

- Yellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance after CommunismFrom EverandYellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance after CommunismNo ratings yet

- Paradoxes of Populism: Troubles of the West and Nationalism's Second ComingFrom EverandParadoxes of Populism: Troubles of the West and Nationalism's Second ComingNo ratings yet

- Otherness and Ethics: An Ethical Discourse of Levinas and Confucius (Kongzi)From EverandOtherness and Ethics: An Ethical Discourse of Levinas and Confucius (Kongzi)No ratings yet

- Men Under Fire: Motivation, Morale, and Masculinity among Czech Soldiers in the Great War, 1914–1918From EverandMen Under Fire: Motivation, Morale, and Masculinity among Czech Soldiers in the Great War, 1914–1918No ratings yet

- 625680Document228 pages625680agnes vdovicNo ratings yet

- Hobsbawm - Language, Culture, and National IdentityDocument17 pagesHobsbawm - Language, Culture, and National Identitytwa900No ratings yet

- Etienne Balibar Race Nation Class PDFDocument1 pageEtienne Balibar Race Nation Class PDFBrandonNo ratings yet

- Jose CasanovaDocument28 pagesJose CasanovaWilliam McClureNo ratings yet

- Bogdan-Petru Maleon - Magnaura (The Imperial University of Constantinople)Document13 pagesBogdan-Petru Maleon - Magnaura (The Imperial University of Constantinople)Maria Magdalena SzekelyNo ratings yet

- LeGoff, Mentality, A New Field For HistoriansDocument18 pagesLeGoff, Mentality, A New Field For HistoriansAdrianDawidWesołowskiNo ratings yet

- The Killing Compartments The Mentality of Mass Murder by Abram de SwaanDocument345 pagesThe Killing Compartments The Mentality of Mass Murder by Abram de SwaanLeãonardo TigreNo ratings yet

- Nations and Nationalism Since 1780-Eric Hobsbawm PPDocument21 pagesNations and Nationalism Since 1780-Eric Hobsbawm PPAnastasia(Natasa) Mitronatsiou100% (10)

- Bourdieu - Algerian LandingDocument29 pagesBourdieu - Algerian LandingdsadsdasdsNo ratings yet

- The Pluriverse of Stefan Arteni's Painting IDocument35 pagesThe Pluriverse of Stefan Arteni's Painting Istefan arteniNo ratings yet

- Steward, Julian 1973 Theoryof Culture ChangeDocument260 pagesSteward, Julian 1973 Theoryof Culture ChangeJuan José González FloresNo ratings yet

- Imagining The TurkDocument30 pagesImagining The TurkFazli CormanNo ratings yet

- Eric Hobsbawm Socialism Has Failed Now Capitalism Is Bankrupt PDFDocument4 pagesEric Hobsbawm Socialism Has Failed Now Capitalism Is Bankrupt PDFRober MajićNo ratings yet

- History: Fernand BraudelDocument17 pagesHistory: Fernand BraudelGiorgos BabalisNo ratings yet

- Orientalist Variations on the BalkansDocument15 pagesOrientalist Variations on the BalkansDimitar AtanassovNo ratings yet

- João Biehl Peter Locke Unfinished - The Anthropology of BecomingDocument415 pagesJoão Biehl Peter Locke Unfinished - The Anthropology of BecomingVictor Hugo Barreto100% (1)

- Nicole Rafter, Michelle Brown - Criminology Goes To The Movies - Crime Theory and Popular Culture-NYU Press (2011)Document240 pagesNicole Rafter, Michelle Brown - Criminology Goes To The Movies - Crime Theory and Popular Culture-NYU Press (2011)Dwiki AprinaldiNo ratings yet

- Castree - Making Sense of Nature - ReviewDocument2 pagesCastree - Making Sense of Nature - ReviewSandra Rodríguez CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Eric Hobsbawm - Peasants and PoliticsDocument22 pagesEric Hobsbawm - Peasants and Politicsportos105874100% (1)

- Caliban and The Witch - A Critical AnalysisDocument23 pagesCaliban and The Witch - A Critical AnalysisΓιώργος ΕγελίδηςNo ratings yet

- 3-John Bellamy Foster - Ecology Against Capitalism-Monthly Review Press (2002)Document180 pages3-John Bellamy Foster - Ecology Against Capitalism-Monthly Review Press (2002)Cengiz YılmazNo ratings yet

- Derrida, Literature and WarDocument20 pagesDerrida, Literature and WarContinuum100% (2)

- Norton 1981 The Myth of British EmpirismDocument14 pagesNorton 1981 The Myth of British EmpirismRuck CésarNo ratings yet

- Marc Augé - 1992 - Non-Lieux - EnglishDocument63 pagesMarc Augé - 1992 - Non-Lieux - Englishneko dimensionNo ratings yet

- The Difficult Topos In-Between: Post-Colonial Theory and East Central EuropeDocument6 pagesThe Difficult Topos In-Between: Post-Colonial Theory and East Central EuropecmjollNo ratings yet

- Balkan Historians As State-BuildersDocument7 pagesBalkan Historians As State-Buildersbibbidi_bobbidi_dooNo ratings yet

- After Defeat How The East Learned To Live With The West (Cambridge TRUE, 2011) - Ayşe ZarakolDocument310 pagesAfter Defeat How The East Learned To Live With The West (Cambridge TRUE, 2011) - Ayşe ZarakolLJ HNo ratings yet

- Wayne C. BoothDocument4 pagesWayne C. BoothM_Daniel_MNo ratings yet

- AAAG1959 - The Nature of Frontiers and Boundaries (Ladis Kristof)Document14 pagesAAAG1959 - The Nature of Frontiers and Boundaries (Ladis Kristof)leticiaparenterNo ratings yet

- Clark Wissler-The Culture Area Concept (1928)Document7 pagesClark Wissler-The Culture Area Concept (1928)ruizrocaNo ratings yet

- Bhabha Transmision Barbarica de La Cultura MemoriaDocument14 pagesBhabha Transmision Barbarica de La Cultura Memoriainsular8177No ratings yet

- X International Association For The StudDocument47 pagesX International Association For The StudMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

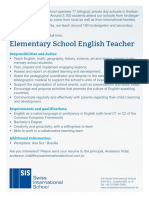

- Elementary School English Teacher: Responsibilities and DutiesDocument1 pageElementary School English Teacher: Responsibilities and DutiesMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

- The World We Have Made?: Individualisation and Personal Life in The 1950sDocument24 pagesThe World We Have Made?: Individualisation and Personal Life in The 1950sMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

- Visitin Youthfull SexualitiesDocument15 pagesVisitin Youthfull SexualitiesMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

- Return of The Subject in Late FoucaultDocument5 pagesReturn of The Subject in Late FoucaultMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

- Visitin Youthfull SexualitiesDocument15 pagesVisitin Youthfull SexualitiesMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

- Inglês F PDFDocument34 pagesInglês F PDFJosé Anibal SilvaNo ratings yet

- Return of The Subject in Late FoucaultDocument5 pagesReturn of The Subject in Late FoucaultMannoel MottaNo ratings yet

- Uriel The Most Unknown ArchangelDocument2 pagesUriel The Most Unknown ArchangelkewltyNo ratings yet

- Dhikr Wa Du'a Al-'Ashura - Invocation & Supplication For AshuraDocument3 pagesDhikr Wa Du'a Al-'Ashura - Invocation & Supplication For AshuraTAQWA (Singapore)100% (7)

- Rig Veda AmericanusDocument120 pagesRig Veda AmericanusLibros de Baubo100% (1)

- The Butbut Tribe: A Glimpse into Kalinga's Headhunting CultureDocument5 pagesThe Butbut Tribe: A Glimpse into Kalinga's Headhunting Culturecurioscat 003No ratings yet

- Revised List of Digital Valuation Center For AYUSH Nursing and Physiotherapy September October 2018Document105 pagesRevised List of Digital Valuation Center For AYUSH Nursing and Physiotherapy September October 2018Supritha Godwin KarkadaNo ratings yet

- Cosmotheism Trilogy William Luther Pierce PDFDocument21 pagesCosmotheism Trilogy William Luther Pierce PDFshitmasterNo ratings yet

- Spells of Magic in MerlinDocument14 pagesSpells of Magic in MerlinClaire Lennon50% (2)

- AnthropologyDocument1 pageAnthropologyMátyás TóthNo ratings yet

- Bruno Latour, On Interobjectivity, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 1996Document11 pagesBruno Latour, On Interobjectivity, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 1996MoocCBT100% (1)

- KalionskiDocument81 pagesKalionskiȘtefan BejanNo ratings yet

- Art and Society in India PDFDocument2 pagesArt and Society in India PDFMuhamed DukmakNo ratings yet

- DOUGLAS, Mary. The Social Control of CognitionDocument17 pagesDOUGLAS, Mary. The Social Control of CognitionemaildoreginaldoNo ratings yet

- CatDocument15 pagesCattejasg82No ratings yet

- Philosophy Education Society IncDocument31 pagesPhilosophy Education Society IncAnonymous lVC1HGpHP3No ratings yet

- Theory For The Evolution of Mesoamerican CivilizationDocument15 pagesTheory For The Evolution of Mesoamerican CivilizationJose Manuel FloresNo ratings yet

- SMRT 195 Broomhall - Ordering Emotions in Europe, 1100-1800 PDFDocument335 pagesSMRT 195 Broomhall - Ordering Emotions in Europe, 1100-1800 PDFL'uomo della RinascitáNo ratings yet

- Archaeology and Anthropology - Brothers in Arms (Inglés) Autor Fredrik FahlanderDocument27 pagesArchaeology and Anthropology - Brothers in Arms (Inglés) Autor Fredrik FahlanderRenzoDTNo ratings yet

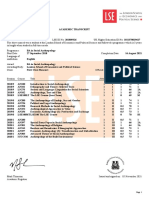

- LSE Academic Transcript SEODocument3 pagesLSE Academic Transcript SEOFaraz AzamNo ratings yet

- FORENSIC 101 NotesDocument22 pagesFORENSIC 101 NotesjohoneyhanyaquimcoNo ratings yet

- OBSERVING THE ECONOMY. by C.A. Gregory and J.C. Altman.: Book Reviews 257Document3 pagesOBSERVING THE ECONOMY. by C.A. Gregory and J.C. Altman.: Book Reviews 257kakienNo ratings yet

- Hegel's View of Human Nature in His AnthropologyDocument24 pagesHegel's View of Human Nature in His AnthropologyidquodNo ratings yet

- Of Gods, Glyphs and KingsDocument24 pagesOf Gods, Glyphs and KingsBraulioNo ratings yet

- Sexuality and Gay Lesbian Movements in The Third WorldDocument27 pagesSexuality and Gay Lesbian Movements in The Third WorldFrankie CruzNo ratings yet

- Social Status and Cultural Consumption PDFDocument27 pagesSocial Status and Cultural Consumption PDFMoi WouNo ratings yet

- Correspondences For HecateDocument6 pagesCorrespondences For HecateRayBoyd100% (6)

- Brokaw, Ollantay The Khipu and Neo-Inca PoliticsDocument27 pagesBrokaw, Ollantay The Khipu and Neo-Inca Politicsg_b_b_bNo ratings yet

- Duran Merk Villa Carlota PDFDocument150 pagesDuran Merk Villa Carlota PDFIanuarius Valencia ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- Anand Sahib - LONGDocument210 pagesAnand Sahib - LONGBharat Sahni100% (1)

- Ethics MoralityDocument14 pagesEthics MoralityUsama Javed100% (1)

- Implication of MythologyDocument2 pagesImplication of MythologyYukiya KanazakiNo ratings yet