Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter V - of The Price of Coal

Chapter V - of The Price of Coal

Uploaded by

Danna GarzónOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter V - of The Price of Coal

Chapter V - of The Price of Coal

Uploaded by

Danna GarzónCopyright:

Available Formats

The Coal Question William Stanley Jevons

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal

"CHEAPNESS and goodness," said Yarranton, "is, and always will be, the great

master and comptroller of trade," and the reader will see that the whole question

of the exhaustion of our mines is a question of the cost of coal. All commerce, in

short, is a matter of price. "Will it pay to do this at this price?" or, "Will it pay

better to do this here at this price or there at that price?" Such are the leading

questions which govern every commercial undertaking in a free system of

industry.

The exhaustion of our mines will be marked pari passu by a rising cost or value

of coal; and when the price has risen to a certain amount comparatively to the

price in other countries, our main branches of trade will be doomed. It will be

well, therefore, to inquire whether there has been any recent serious rise in the

price of coal such as would be the sign of incipient exhaustion. Had a

considerable recent rise occurred, as I have heard asserted, it might be argued

that no such evil results have followed as alarmists prophesy, and then the

optimist would conclude that, perhaps, after all, "dear coal" is not the fatal thing

some suppose; this country may surmount that evil, it will be said, as it has

surmounted worse evils.

From what reliable accounts I have been able to meet with, it is certain that

there has been no such recent rise of price as could at all operate as a check

upon our industry. Yet it is certain that coal has been cheaper in the past than it

can again be, and that in the Great Northern market the growth of demand

during the last century has been accompanied by a considerable but indefinite

rise of price.

Where coal, indeed, used formerly to be had almost for the asking, it now bears a

fair price. In the palmy day of the Staffordshire "Thick Coal" the price of the best

large coal was 6s. per ton of 21 cwts., and 120 lbs. to the cwt., or 5s. 4d. per ton

of 2,240 lbs. Coal was a drug about Birmingham, "so much so, as to cause the

coalowners to give great extra weight.... There are many other veins at present

not thought worth getting, or from one to three yards thick; inferior coals are

sold at 3s. per ton, and from that upwards, in proportion to their quality; the

small coals, for working engines, are sold from 1s. to 1s. 6d. per ton; the supply

produced for the manufactures of the country would always be sufficient, in my

opinion, without increasing the present price, as there are many new collieries

now opening."[1]

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal 51

The Coal Question William Stanley Jevons

The anticipations of the Ironmaster who gave this opinion before the Committee

of 1800 have not proved true. The price of best coal in Staffordshire is now nine

shillings or more per ton, and many writers concur in stating that the

magnificent "Thick Coal" of South Staffordshire has been either used or wasted

away. The wonderful "black country" already leans for its supplies of coal and

ore upon neighbouring parts;[2] it seems to be already overshadowed by the

approaching decline of prosperity. "He that liveth longest, let him fetch fire

furthest," was a proverb quoted by Dudley,[3] two and a half centuries ago, with

reference to the lamentable waste of the Thick Coal, and now the force of the

proverb is becoming apparent.

The late strike of Staffordshire miners was occasioned by the high price of coal.

The activity of the iron trade for the last year or two had led to several advances

in the price of coal and rate of wages; but though the price of iron remained

pretty high, it was found the trade could not bear the cost of coal. To prevent

injury to the staple industry of the district, the coal proprietors, somewhat

arbitrarily, determined to reduce the price of coal by cutting down the wages of

the miners, and in this they have been at least temporarily successful. But it is

feared that the interruption of business occasioned by the strike may have

already contributed to forward that migration of the iron trade to the newer coal-

fields which must soon take place.

It is almost impossible to get such general and uniform statements of the price of

coal as would warrant us in drawing comparisons over long periods of time. The

variations in the quality, size, and distance of supply constantly affect the price,

independently of duties and other obstacles. Almost all the quotations of prices

refer to the London market, and are useless, because the prices there are not

only affected by freights, but have been burdened, more or less, by duties and

charges of a most complicated character.

The only series of prices I have been able to make out gives the average price of

the best large coal as put free on board at Newcastle, and the other shipping

places of the North. The first two prices (1771 and 1794) are derived from the

Report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Coal Trade in

1830 (p. 7). The prices of 1801-1851, are from a table of yearly prices published

by Mr. Porter, in his "Progress of the Nation" (p. 277), and are the average

shipping prices as returned to the Coal Exchange in London under Act of

Parliament. The last price (1860) is an average computed for the General

Committee of the Coal Trade of Newcastle, and communicated to the Mining

Record Office. [4]

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal 52

The Coal Question William Stanley Jevons

Average Shipping Price of Newcastle Coal

Year. s. d.

1771... 5 4 per ton.

1794... 7 6 per ton.

1801... 10 4 per ton.

1811... 13 0 per ton.

1821... 12 8 per ton.

1831... 12 4 per ton.

1841... 10 6 per ton.

1850... 9 6 per ton.

1860... 9 0 per ton.

This is probably as good and comparable a series of prices as could be got; yet it

is very difficult to draw inferences from it beyond the contradiction of any recent

considerable rise. The great rise of price up to 1811 was more or less due to the

depreciation of gold and paper currency, or to the other causes, whatever they

may have been, of the great general rise of prices. The subsequent fall is, of

course, partly due to the restoration of our currency, and to the other debatable

causes of a general fall of prices.[5]

There are, however, at least two other circumstances not to be lost sight of in

comparing early and late prices of coal.

Firstly, there is the limitation of the vend, an arrangement which used to exist

among the coal proprietors of the North, to limit the amount sold by any colliery,

in order that each colliery might have a share of the trade proportional to its

capabilities. This combination maintained itself at intervals for about two

centuries, and was much complained of because it was supposed to raise the

price of coal. It may have had some effect, especially upon those better kinds of

coal of which the price is quoted.

Secondly, there is the practice of screening coals, whereby a considerable

portion of the coal raised at the beginning of the century used to be separated

out and burnt as waste, the whole cost of raising the coal being paid in the price

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal 53

The Coal Question William Stanley Jevons

of the large coal sold. Though coals are still generally screened, the "seconds,"

"nuts," and even the "dead small," or "slack," are usually sold for manufacturing

purposes at prices proportional to the size of the coal. The total price thus

returned is increased by more than is represented in the price of the large coal.

Both the limitation of the vend and the practice of screening would thus tend to

raise the earlier quotations of price of large coal, as compared with late

quotations, and thus disguise the real rise of price due to the growing demand

and the depth of the mines.

I take it, therefore, to be pretty certain that the cost of the best quality of

Newcastle coal has been considerably more than doubled within a century by the

growing depth of the collieries. It is not to be said that trade is much affected by

the price of the very best coals, which are chiefly valued for household purposes.

But from the price of such coal we learn what we should have to pay were all

coals drawn from the depths of 1,000 or 2,000 feet or more. The mines of South

Wales, Scotland, and Yorkshire are yet shallow, and the coal cheap enough. The

cost of the coal, especially, which supports the great and rising iron trade in

South Wales and Scotland, is only four or five shillings per ton.

The following are some returns of the price of coal published by Mr. Hunt in the

Mineral Statistics for 1860:-

Description of Coal Price per Ton

s. d.

Newcastle... House Coal... 9 0

Steam... 8 0

Gas, Coking, and 5 6

Manufacturing

Derbyshire... Best Coal... 9 0

Common... 6 6

Cost of Getting...5s. to 5 6

North Staffordshire... Best... 9 2

Common... 6 0

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal 54

The Coal Question William Stanley Jevons

Cost of Getting...2s. 4 6

6d. to

Lancashire... Best Coal... 6 3

Lately... 5 6

South Wales and Large Coal... 6 6

Monmouthshire...

Small... 4 6

Scotland... Average... 4 0

Cost of Getting... 2 8

The average cost of getting coal throughout the country was stated to be 4s. 10d.

per ton, not including profits, rent, and other charges.

In the very various prices of coal from the several collieries of the Newcastle

district, we have evidence of the rise of price due to the depth of mines. Shipping

prices of coal are given in full detail in the Report of the Committee of 1838 (p.

240); and taking the coals classed as Newcastle Wallsend only, we find the price

varying from 6s. 6d. to 11s. 6d., the nuts and small coal ranging down to 3s. 9d.

It is obvious that the difference of five shillings per ton in Wallsend coal must

either be absorbed by the expenses of deep mining, or else it must make the

fortune of the proprietors or workers of the mines. That in some cases prodigious

profits are made, as in the case of the original Wallsend mine, is well known. But

this cannot usually be the case, otherwise the wide areas of land yet known to

contain untouched seams of coal of the finest qualities, would at once be broken

up by speculators, who are never wanting. That deep mines are so deliberately

opened is a sufficient proof that the highest prices obtained are, taking all

mining risks and charges into account, only an average equivalent for the capital

invested. These deep pits can only be undertaken at present in search of coal of

the finest household quality. The Monkwearmouth Pit was sunk to win the

Hutton seam, which yields coal of the highest possible character. The Dukinfield

Deep Pit was undertaken to follow the celebrated Lancashire "Black Mine," a

four feet seam of the finest coal, selling for 10s. per ton at the pit's mouth, the

small coal returning 5s. 6d. per ton.

The high prices, which are necessary in order to tempt speculators to undertake

deep mining, afford a rough but sure indication of the effect of depth upon the

cost of coal. When the general depth of coal workings has increased to 2,000

feet, little or no coal will be sold for less than 10s. per ton, and the choice large

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal 55

The Coal Question William Stanley Jevons

coal will have risen to a much higher price. Our iron and general manufacturing

industries will have to contend with a nearly double cost of fuel. And when with

the growth of our trade and the course of time our mines inevitably reach a

depth of 3,000 or 4,000 feet, the increasing cost of fuel will be an incalculable

obstacle to our further progress.

Notes

1. Evidence of Alex. Raby. First Report on Coal Trade, 1800, pp. 76, 77.

2. See Chap. XV.

3. Metallum Martis, p. 8.

4. Mineral Statistics for 1860, p. xxiii.

5. The comparison in the First Edition of the change of price of coal with

the average change of price of commodities was erroneous, owing to a

numerical oversight. The fall of prices between 1794 and 1860 was in

the ratio of 100 to 81. See Journal of the Statistical Society, June 1865,

p. 294.

Chapter V - Of the Price of Coal 56

You might also like

- Instant Download Smith and Robersons Business Law 17th Edition Mann Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Smith and Robersons Business Law 17th Edition Mann Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapterrappelpotherueo100% (7)

- Assignment 1 - 2021 - 2022Document4 pagesAssignment 1 - 2021 - 2022Assya El MoukademNo ratings yet

- Statement 2023 5Document1 pageStatement 2023 5MasoomaIjazNo ratings yet

- Base Rate Percentage + Ratio and ProportionDocument15 pagesBase Rate Percentage + Ratio and Proportionrommel legaspiNo ratings yet

- Ansi O5.1-2002Document49 pagesAnsi O5.1-2002henryNo ratings yet

- Tin-From Ore To IngotDocument6 pagesTin-From Ore To IngotAbdullah Badawi BatubaraNo ratings yet

- Economies of Large Scale ProductionDocument14 pagesEconomies of Large Scale ProductionPrabhkeert Malhotra100% (2)

- Chapter V - of The Price of CoalDocument6 pagesChapter V - of The Price of CoalDanna GarzónNo ratings yet

- Lectures On Popular and Scientific Subjects by John Sutherland Sinclair, Earl of CaithnessDocument53 pagesLectures On Popular and Scientific Subjects by John Sutherland Sinclair, Earl of CaithnessGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Lectures on Popular and Scientific SubjectsFrom EverandLectures on Popular and Scientific SubjectsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal FixDocument5 pagesJurnal FixEfa OctaviaNo ratings yet

- Lessons From The Age of CoalDocument15 pagesLessons From The Age of CoalNishanth Navaneetha GopalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Clark 2007 Coal and The Industrial Revolution 1700-1869Document34 pagesClark 2007 Coal and The Industrial Revolution 1700-1869Z MitchellNo ratings yet

- The Story of a Piece of Coal What It Is, Whence It Comes, and Whither It GoesFrom EverandThe Story of a Piece of Coal What It Is, Whence It Comes, and Whither It GoesNo ratings yet

- The Story of a Piece of Coal: What It Is, Whence It Comes, and Whither It GoesFrom EverandThe Story of a Piece of Coal: What It Is, Whence It Comes, and Whither It GoesNo ratings yet

- The Underground City; Or, The Black Indies (Sometimes Called The Child of the Cavern)From EverandThe Underground City; Or, The Black Indies (Sometimes Called The Child of the Cavern)No ratings yet

- 500 Years AgoDocument2 pages500 Years AgoNiraj KotharNo ratings yet

- CoalDocument17 pagesCoalMsiva RajNo ratings yet

- The Forgotten Canals of Yorkshire: Wakefield to Swinton via BarnsleyFrom EverandThe Forgotten Canals of Yorkshire: Wakefield to Swinton via BarnsleyNo ratings yet

- Step Into My LaboratoryDocument5 pagesStep Into My LaboratoryArif UpiNo ratings yet

- Solid Black and Liquid Gold by Gerry StaleyDocument154 pagesSolid Black and Liquid Gold by Gerry StaleyAustin Macauley Publishers Ltd.No ratings yet

- First Is Difficult Its It Is LBS., LBS., Lbs. All It Is ItDocument1 pageFirst Is Difficult Its It Is LBS., LBS., Lbs. All It Is ItreacharunkNo ratings yet

- The Underground City, or, the Child of the CavernFrom EverandThe Underground City, or, the Child of the CavernRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (55)

- PDF of Siapkah Kita Mempertanggungjawabkan Segalanya Eka Kartini Gaffar Full Chapter EbookDocument69 pagesPDF of Siapkah Kita Mempertanggungjawabkan Segalanya Eka Kartini Gaffar Full Chapter Ebookkalindarosef75100% (5)

- Blackwell 1852Document2 pagesBlackwell 1852AmlaanNo ratings yet

- How Oil Became KingDocument7 pagesHow Oil Became Kingscribduser000001No ratings yet

- Comments On Pamela Nightingale, English Medieval Weight-Standards Revisited'Document6 pagesComments On Pamela Nightingale, English Medieval Weight-Standards Revisited'sonositeNo ratings yet

- The Engineer2Document20 pagesThe Engineer2seb211No ratings yet

- Jan., Qro.1 Current Topics.: Bztl-ZetinDocument2 pagesJan., Qro.1 Current Topics.: Bztl-Zetinarno griecoNo ratings yet

- The Pattern Halfpennies and Farthings of Anne / by C. Wilson PeckDocument23 pagesThe Pattern Halfpennies and Farthings of Anne / by C. Wilson PeckDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Nature and Occurrence of Coal SeamsDocument6 pagesNature and Occurrence of Coal SeamsSheshu Babu100% (2)

- Argus US Export CoalDocument2 pagesArgus US Export CoalMohammad SofiyudinNo ratings yet

- Engineering Vol 56 1893-10-13Document33 pagesEngineering Vol 56 1893-10-13ian_newNo ratings yet

- Engineering Vol 69 1900-06-08Document33 pagesEngineering Vol 69 1900-06-08ian_newNo ratings yet

- 2019 01 PDFDocument68 pages2019 01 PDFАлиса Пестрова100% (1)

- Rotary Kiln-1910 PDFDocument96 pagesRotary Kiln-1910 PDFSunday Paul100% (1)

- Instant Download Test Bank For Organic Chemistry 6th Edition Brown PDF FullDocument32 pagesInstant Download Test Bank For Organic Chemistry 6th Edition Brown PDF FullDouglasWrightcmfa100% (13)

- Fossil Fuels: Coal: HistoryDocument8 pagesFossil Fuels: Coal: HistoryCharles BinuNo ratings yet

- Kimmeridge Why KimmeridgeDocument16 pagesKimmeridge Why KimmeridgeDaniel ThamNo ratings yet

- The Underground CityDocument208 pagesThe Underground CityZhanna VozbrannaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Definitions, Units & Measures (Ajay)Document6 pagesChapter 2 Definitions, Units & Measures (Ajay)VanrajNo ratings yet

- Fisher - The Portugal Trade - A Study of Anglo-Portuguese Commerce 1700-1770-123-137Document15 pagesFisher - The Portugal Trade - A Study of Anglo-Portuguese Commerce 1700-1770-123-137Pablito PablitoNo ratings yet

- Lead Smelting and Refining, With Some Notes on Lead MiningFrom EverandLead Smelting and Refining, With Some Notes on Lead MiningNo ratings yet

- SLMR 1912 11 15Document20 pagesSLMR 1912 11 15Russell HartillNo ratings yet

- Department of Mining Engineering (NITK)Document26 pagesDepartment of Mining Engineering (NITK)ankeshNo ratings yet

- Keynes FineGoldv 1930Document6 pagesKeynes FineGoldv 1930Jorge “Pollux” MedranoNo ratings yet

- An Unreliable History of SteelmakingDocument2 pagesAn Unreliable History of SteelmakingFeliciano Gámez DuarteNo ratings yet

- Komatsu Articulated Dump Truck Hm400!5!10001 and Up Shop Manual Sen06519 05Document22 pagesKomatsu Articulated Dump Truck Hm400!5!10001 and Up Shop Manual Sen06519 05pamriggs091289bjg100% (62)

- The Rise and Progress: KitchenerDocument38 pagesThe Rise and Progress: KitchenerKnewage7No ratings yet

- Chapter 16Document58 pagesChapter 16derpy the derpNo ratings yet

- Biography of T. Adeola OdutolaDocument198 pagesBiography of T. Adeola OdutolaCarlos Castro100% (4)

- Final Account (Solution) RainbowDocument4 pagesFinal Account (Solution) RainbowIsteehad RobinNo ratings yet

- Important Vocabulary Flashcards Meaning and Example Sentences With PDFDocument20 pagesImportant Vocabulary Flashcards Meaning and Example Sentences With PDFcxzczxNo ratings yet

- Nepalese Tax Structure: An Analytical PerspectiveDocument12 pagesNepalese Tax Structure: An Analytical Perspectiveभोला भण्डारीNo ratings yet

- Krsmanc2875 BDocument97 pagesKrsmanc2875 BasitarekNo ratings yet

- Walden Economy ThesisDocument8 pagesWalden Economy Thesisoeczepiig100% (2)

- Asktrade Mining Documents - 20230323 - 0001Document6 pagesAsktrade Mining Documents - 20230323 - 0001Sindile MakupulaNo ratings yet

- History Great Depression Research EssayDocument6 pagesHistory Great Depression Research Essayapi-704337916No ratings yet

- Thesis Oil IndustryDocument8 pagesThesis Oil Industrybsgyhhnc100% (2)

- SHFC High Density Housing ProgramDocument17 pagesSHFC High Density Housing ProgramraraNo ratings yet

- NIFTY 500: 2019 2020 (Upto 16-04-2020)Document11 pagesNIFTY 500: 2019 2020 (Upto 16-04-2020)Power of Stock MarketNo ratings yet

- PYQs - International - Economics - 2Document5 pagesPYQs - International - Economics - 2TusharNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions Question List and Exercices Valuation With Full SolutionsDocument5 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Question List and Exercices Valuation With Full SolutionsAbdelhadi KaoutiNo ratings yet

- KMUT - NEW - POST CRA LetterDocument12 pagesKMUT - NEW - POST CRA LetterdineshmarginalNo ratings yet

- Graphic Designer: WantedDocument1 pageGraphic Designer: WantedByron Echo PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Plant Visit - 02.08.21Document5 pagesPlant Visit - 02.08.21bionics enviro techNo ratings yet

- FINANCEDocument2 pagesFINANCEBianca Therese BoltronNo ratings yet

- Financial Leverage and Performance of Nepalese Commercial BanksDocument23 pagesFinancial Leverage and Performance of Nepalese Commercial BanksPushpa Shree PandeyNo ratings yet

- Managerial Acc QnaireDocument5 pagesManagerial Acc QnaireMutai JoseahNo ratings yet

- SOP - A.01.01. Petty Cash AdvanceDocument14 pagesSOP - A.01.01. Petty Cash AdvanceVenesya Widya AuliaNo ratings yet

- Rosario Acero S.A Case Study SolutionDocument3 pagesRosario Acero S.A Case Study SolutionMrittika SahaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5Document84 pagesLecture 5Lee Li HengNo ratings yet

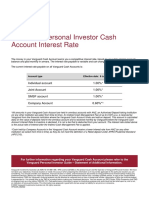

- AU-Vanguard Personal Investor-Cash Account Interest RateDocument1 pageAU-Vanguard Personal Investor-Cash Account Interest RateNick KNo ratings yet

- Consumer Theory MCQ With SolutionsDocument2 pagesConsumer Theory MCQ With SolutionsMarley EssamNo ratings yet