Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Virtual Memory: Virtual Memory, Automatically Manages The Transfer of Pieces of Code

Uploaded by

king vjOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Virtual Memory: Virtual Memory, Automatically Manages The Transfer of Pieces of Code

Uploaded by

king vjCopyright:

Available Formats

10.

Virtual Memory

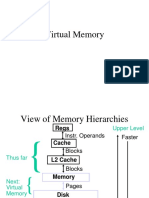

In a typical memory hierarchy for a compute there are three levels: the

cache, the main memory and the external storage, usually the disk. So far

we have discussed about the first two levels of the hierarchy. the cache and

the main memory; as we saw the cache contains and provides fast access to

those parts of the program that are most recently used. The main memory is

for the disk, what the cache is for the main memory: the programmer has

the impression of a very fast, and very large memory without caring about

the details of transfers between the two levels of the hierarchy.

The fundamental assumption of virtual memory is that programs do not

have to entirely reside in main memory when executed, the same way a

program does not have to entirely fit in a cache, in order to run.

The concept of virtual memory has emerged primarily as a way to relieve

programmer from the burden of accommodating a large program in a small

main memory: in the early days the programmer had to divide the program

into pieces and try to identify those parts that were mutually exclusive, i.e.

they had not to be present at the same moment in memory; these pieces of

code, called overlays, had to be loaded in the memory under the user

program control, making sure at any given time the program does not try to

access an overlay not in memory.

Virtual memory, automatically manages the transfer of pieces of code/

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

169

10 Virtual Memory

data between the disk and main memory and conversely.

At any moment of time, several programs (processes) are running in a

computer; however it is not known at compile time, which will be the other

programs with which the compiled program will be running in a computer.

Of course we discuss here about systems that allow multiprogramming,

which is the case with most of the today's computers: a good image for this

is any IBM-PC running Windows, where several applications may be

simultaneous active. Because several programs must share, together with

the operating system, the same physical memory, we must somehow ensure

protection, that is we must make sure each process is working only in its

own address space, even if they share the same physical memory.

Virtual memory also provides relocation of programs; this means that a

program can be loaded anywhere in the main memory. Moreover, because

each program is allocated a number of blocks in the memory, called pages,

the program has not to fit in a single contiguous area of the main memory.

Usually virtual memory reduces also the time to start a program, as not all

code and data has to be present in the memory to start; after the minimum

amount has been brought into main memory, the program may start.

10.1 Some Definitions

The basic concepts of a memory hierarchy apply for the virtual memory

(the main memory secondary storage levels of the hierarchy). For historical

reasons the names we are using, when discussing about virtual memory, are

different:

• page or segment are the terms used for block;

• page fault is the term used for a miss.

The name page is used for fixed size blocks, while the name segment is

used for variable size blocks.

Minimum Maximum

Page size 512 Bytes 16 Kbytes

Segment size 1 Byte 64 KB - 4 MB

Until now we have not been concerned about addresses: we did not make

any distinction between an addressed item and a physical location in

memory. When dealing with virtual memory we must make a clear

distinction between the address space of a system (the range of addresses

the architecture allows), and the physical memory location in a given

hardware configuration:

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

170

10.1 Some Definitions

• the virtual address is the address the CPU issues;

• the physical address results from translating the virtual

address (using a hardware and software combination), and can be

used to access the main memory.

The process of translating virtual addresses into physical addresses (also

named real addresses) is called memory mapping, or address translation.

The virtual address can be viewed as having two fields, the virtual page/

segment number and the offset inside the page/segment. In the case the

system uses a paged virtual memory things are simple, there a fixed size

field corresponding to offset and the virtual page number is also of fixed

size; with a larger page size the offset field gets larger but, in the mean time

fewer pages will fit in the virtual address space, and the page number field

gets smaller: the sum of sizes of the two fields is constant, the size of an

address issued by the CPU.

Virtual page number Page offset

MSB LSB

Obviously the number of virtual pages has not to be the same with the

number of pages that fit in the main memory, and, as a matter of fact,

usually there much more virtual pages than physical ones.

Example 10.1 VIRTUAL PAGE AND OFFSET:

A 32 bit address system, uses a paged virtual memory; the page size is 2

KBytes. What is the virtual page and the offset in the page for the virtual

address 0x00030f40?

Answer:

For a page size of N Bytes the number of bits in the offset field is log2N. In

the case of a 2 KBytes page there are:

log2211 = 11 bits

Therefore the number of bits for the page number is:

32 - 11 = 21

which means a total of 221 = 2 Mpages. The binary representation of the

address is:

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

171

10 Virtual Memory

0000 0000 0000 0011 0000 1 111 0100 0000

31 11 10 0

The given virtual address identifies the virtual page number 0x61 = 9710;

the offset inside the page is 0x740 = 185610.

When the virtual memory is segmented, the two fields of the virtual

address have variable length; as a result the CPU must issue two words for

a complete address, one which specifies the segment, and the other one

specifying the offset inside the page. It is therefore important to know from

an early stage of the design if the virtual memory will be paged or

segmented as this affects the CPU design. A paged virtual memory is also

simpler for the compiler.

Another drawback of segmented virtual memory is related to the

replacement problem: when a segment has to be brought into main memory

the operating system must find an unused, contiguous area in memory

where the segment fits. This is really hard as compared with the paged

approach: all pages have the same size, and it is trivial to find space for the

page being brought.

The main differences between the cache-main_memory and the

main_memory_disk can be resumed as follows:

• caches are hardware managed while the virtual memory is

software managed (by the operating system). As the example 7.5

points out, the involvement of the operating system in the

replacement decision, adds very little to the huge disk access time.

• the size of the cache is independent of the address size of the

architecture, while for the virtual memory it is precisely the size of

the address which determines the its size.

• besides its role as the bottom level of the memory hierarchy, the

disk also holds the file system of the computer.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

172

10.1 Some Definitions

Virtual address

Virtual page number Page offset

Page table

Physical address

FIGURE 10.1 For a paged virtual memory the page’s physical address (at outputs of page table) is

concatenated with the page offset to form the physical address to the main memory.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

173

10 Virtual Memory

Virtual address

Segment number Segment offset

Segment table

Physical address

FIGURE 10.2 For a segmented virtual memory the offset is added to the segment’s physical address

to form the address to the main memory (the physical address).

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

174

10.2 How Virtual Memory Works

10.2 How Virtual Memory Works

As with any memory hierarchy, the same basic questions have to be

answered.

Where are blocks placed in main memory

Due to the huge miss penalty, the design of the virtual memory focuses in

reducing the miss rate. The block placement is a good candidate for

optimization. As we saw when discussing about caches, an important

source for misses are the conflicts in direct mapped and set associative

caches; a fully associative cache eliminates these conflicts. While fully

associative caches are very expensive and slow down the clock rate, we can

implement a fully associative mapping for the virtual memory. That means

any virtual page can be placed anywhere in the physical memory. This is

possible because it is in software where misses are handled.

Is the block in the memory or not?

A table ensures the address translation. This table is indexed with the

virtual page/segment number to find the start of the physical page/segment

in main memory. There is a difference between paging and segmentation:

• paging: the full address is obtained by concatenating the page's

physical address and the page offset, as in Figure 10.1

• segmentation: the full address is obtained by adding the segment

offset to the segment's physical address, as in Figure 10.2

Each program has its own page table, which maps virtual page numbers to

physical addresses (a similar discussion can be made about segmentation,

but we shall concentrate on paging). This table resides in main memory,

and the hardware must provide a register whose content points to the start

of the page table: this is the page table register, and in our machine can be

one of the registers in the general purpose set, restricted to be used only for

this purpose.

As it was the case with caches, each entry in the page table contains a bit

which indicated if the page corresponding to that entry is in the main

memory or not. This bit, the valid bit is set to Valid (1) whenever a page is

being brought into the main memory, and to Non-valid (0) whenever a page

is replaced in main memory.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

175

10 Virtual Memory

Example 10.2 PAGE TABLE SIZE:

A 32 bit address system, has a 4 MBytes main memory. The page size is 1

KByte. What is the size of the page table?

Answer:

The page table is addressed with the page number field in the virtual

address. Therefore the number of lines in the page table equals the number

of virtual pages. The number of virtual pages is:

address_space [ Bytes ]

virtual_pages = --------------------------------------------------------

page_size [ Bytes ]

32

2 22

virtual_pages = --------- = 2 = 4 Mpages

10

2

The width of each line in the page table equals the width of the page

number field in the virtual address. If the number of virtual pages is 222,

then the line width is 22 bits. It results that the size of the page table is:

page_table_size = number_of_entries * line_size

page_table_size = 222*22 bits = 11.5 Mbyte!!

As the above example points out the size of the page table can be

impressive, in so much that in the example, it does not fit in the memory.

However, most of the entries in the page table have the valid bit equal to 0

(Non-valid); only a number of entries equal to the number of pages that fit

in the main memory have the valid bit equal to 1; that is only:

22

main_memory_size 2 12

----------------------------------------------- = ------

10

- = 2 = 4096 entries

page_size 2

have the valid bit equal to 1; this represents only from the total number of

entries in the page table.

• One way to reduce the page table size is to apply a hash function

to the virtual address, such that the page table must have only so

many entries as pages in the main memory, 4096 for the example

10.2. In this case we have an inverted page table, The drawback

is a more involved access, and some extra hardware.

• Another way to keep a smaller page table is to start with a small

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

176

10.2 How Virtual Memory Works

page table and a limit register; if the virtual page number is larger

than the content of the limit register, then the page table must be

increased, as the program requires more space. The underlying

explanation for this optimization is the principle of locality: the

address space won't be uniformly accesses, instead, addresses

concentrate in some areas of the total address space.

• Finally, it is possible to keep the page table paged by itself, using

the same idea that lags behind the virtual memory. namely that

only some parts of it will be needed at any time in the execution of

a program.

Even if the system uses an inverted page table, its size is so large that it

must be kept in the main memory. This makes every memory access

longer: first the page table must be in the memory to get the physical page

address, and only then can the data be accessed. The principle of locality

works again and helps improving the performance. When a translation

from a virtual page to physical one is made, it is probable that it will be

done again in the future, due to spatial and temporal locality inside a page.

Therefore the idea is to have a cache for translations, which will make most

of the translations very fast; this cache, that most new designs provide, is

called translation lookaside buffer or TLB.

What block should be replaced in the case of a miss?

Both because the main purpose is to reduce the miss rate and because the

large times involved in the case of a miss allow a software handling, the

most used algorithm for page replacing is Least Recently Used (LRU),

which is based on the assumption that replacing the page that has not been

used for the longest time in the past will hurt the least the hit rate, in that

probably it won't be needed in the near future as it has not been needed in

the past.

To help the operating system take a decision, the page table provides a bit,

the reference bit also called the use bit, which indicates if the page was

accessed or not. The best candidate for a replacement is a page that has not

been referenced in the past; if all pages in the main memory have been

referenced, then the best candidate is one page that has been little used in

the past and has not been written, thus saving the time for writing it back

on the disk.

How are writes handled?

In the case of caches there are two options to manage the writes: write

through and write back, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

177

10 Virtual Memory

For virtual memory there is only one solution: write back. It would be

disastrous to try writing on disk at every write; remember that the disk

access time is in the millisecond range, which means hinders of thousands

of clock cycles.

The same improvement that was possible with caches can be used for

virtual memory: each entry in the page table has a bit, the dirty bit, which

indicates if the content of the table was modified as a result of a write.

When a page is brought in main memory, the dirty bit is set to Non-dirty

(0); the first write in that page will change the bit to Dirty (1). When it

comes to replacing a page, the operating system will prefer to replace a

page that has not been written because this saves the time of writing out a

page to the disk, again a milliseconds amount of time.

10.3 More About TLB

The TLB is a cache specially designed for page table mappings. Each entry

in the TLB has the two basic fields we found in caches: a tag field which is

as wide as the virtual page number, a data field which is the size of the

physical page number, and several bits that indicate the status of the TLB

line or of the page associated with it; these bits usually are a dirty bit which

indicates if the corresponding page has been written, a reference bit which

indicates if the corresponding page has been accessed, maybe a write

protection bit which indicates if writes are allowed in the corresponding

page. Note that these bits correspond to the same bits in the page table.

At every memory reference the TLB is accessed with the virtual page

number field of the virtual address. If there is a hit, then the physical

address is formed using the data field in the TLB for that entry,

concatenated with the page offset. If there is a miss in the TLB, the control

must determine if there is a real page fault or a simple TLB miss which can

be quickly resolved by updating the TLB entry with the proper information

from the page table residing in main memory. In the case of a page fault the

CPU gets interrupted, and the interrupt handler will be charged to take the

necessary steps to solve the fault.

Figure 10.3 presents the logical steps in addressing the memory; the

diagram assumes that the cache is addressed using the physical address.

The main implication of this scheme is that both accesses, to the TLB and

to the cache, are serialized; the time needed to get an item from the

memory, in the best case, is the access time in TLB (assume there is a TLB

hit), plus the access time in the cache (assume there is a cache hit).

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

178

10.3 More About TLB

Virtual Address

TLB

Yes No

TLB hit

TLB miss

Yes

Write No

Upgrade dirty bit in TLB

Cache read

Cache write

Yes No Yes No

Cache hit Cache hit

Process cache

Data to CPU read miss

Process cache

Write in cache write miss

FIGURE 10.3 Steps in read/write a system with virtual memory and cache.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

179

10 Virtual Memory

Certainly this is troubling because we would like to get an item from the

cache in the same clock cycle the CPU issues the address; with the TLB it

is probably impossible to do this, unless the clock cycle is stretched to

accommodate the total access time.

Another possibility is the CPU to access the cache using an address that is

totally or partial virtual: in this case we have a virtually addressed cache.

For the virtually addressed caches, there is a benefit, shorter access times,

and a big drawback: the possibility of aliasing. Aliasing means that an

object has more than one name, in this case more than one virtual address

for the same object; this can appear when several processes access some

common data. In this case an object may be cached in two (or more)

locations, each corresponding to a different virtual address. The

consequence is that a one process may change data without the other ones

being aware of this. Dealing with this problem is a fairly difficult problem.

A final comment about TLB: it is usually implemented as a fully

associative cache, thus having a smaller miss rate than other options, with a

small number of lines (tens) to reduce the cost of a fully associative cache.

For a small number of words even the LRU replacing algorithm becomes

tempting and feasible.

10.4 Problems In Selecting a Page Size

There are factors that favor a larger page size and factors that favor a small

page size. Here are some. Here are some that favor a large page size:

• the larger the page size is the smaller is the page table, thus saving

space in main memory;

• a larger page size makes transfers from/to disk be more efficient,

in that given the big access times, it is worth transferring more

data once the proper location on the disk has been accessed.

As for factors that favor a small page size, here are some:

• internal fragmentation: if the space used by a program is not a

multiple of the page size, then there will be wasted space because

the unused space in the page(s) can not be used by other programs.

If a process has three segments (text, heap, stack), then the wasted

space is on the average 1.5 pages. As the page size increases the

wasted space gets more relevant

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

180

10.4 Problems In Selecting a Page Size

• wasted bandwidth: this is related to the internal fragmentation

problem. When bringing a page in memory we also transfer the

unused space in that page.

• start time: with a smaller page many small processes will start

faster.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

181

10 Virtual Memory

Exercises

10.1 Draw the block schematic of a 32 bit address system, with pages of

4KBytes. The cache has 8192 lines, each 8 words wide. Assume that the

cache is word addressable.

10.2 With a TLB and cache there are several possibilities of misses: TLB

miss, cache miss, page fault or combinations of these ones. List all possible

combinations and indicate in which circumstances they can appear.

Virgil Bistriceanu Illinois Institute of Technology

182

You might also like

- Apple CompanyDocument33 pagesApple CompanyKiranUmarani76% (17)

- Anatomy of A Program in Memory - Gustavo DuarteDocument41 pagesAnatomy of A Program in Memory - Gustavo DuarteRigs JuarezNo ratings yet

- J Nativememory Linux PDFDocument37 pagesJ Nativememory Linux PDFanguemar78No ratings yet

- Anatomy of A Program in MemoryDocument5 pagesAnatomy of A Program in Memorythong_bvtNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management of Technology Plan For AppleDocument14 pagesStrategic Management of Technology Plan For AppleDesiree Carter/Morris100% (1)

- 2 Virtual MemoryDocument23 pages2 Virtual Memoryshailendra tripathiNo ratings yet

- Contiguous Memory AllocationmeanDocument7 pagesContiguous Memory AllocationmeananitaNo ratings yet

- Onur 447 Spring15 Lecture20 Virtual Memory AfterlectureDocument89 pagesOnur 447 Spring15 Lecture20 Virtual Memory AfterlectureshravaniNo ratings yet

- Virtual MemoryDocument13 pagesVirtual MemoryHira KhyzerNo ratings yet

- 11: Paging Implementation and Segmentation: Page SizeDocument12 pages11: Paging Implementation and Segmentation: Page SizeSiva SrinivasNo ratings yet

- Logical AddressDocument5 pagesLogical Addressanjali gautamNo ratings yet

- CS 558 Operating System 2Document9 pagesCS 558 Operating System 2Cesar CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Com Roan in & Ar It ReDocument35 pagesCom Roan in & Ar It ReWaseem Muhammad KhanNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - Operating System - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inDocument17 pagesUnit 4 - Operating System - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inVEDANSH PARGAIEN CO20366No ratings yet

- Os Memory ManagementDocument6 pagesOs Memory ManagementMd Omar FaruqNo ratings yet

- Memory ManagmentDocument24 pagesMemory ManagmentRamin Khalifa WaliNo ratings yet

- Cache Memory ADocument62 pagesCache Memory ARamiz KrasniqiNo ratings yet

- Virtual Memory and Memory Management Requirement: Presented By: Ankit Sharma Nitesh Pandey Manish KumarDocument32 pagesVirtual Memory and Memory Management Requirement: Presented By: Ankit Sharma Nitesh Pandey Manish KumarAnkit SinghNo ratings yet

- Lectures On Memory Organization: Unit 9Document32 pagesLectures On Memory Organization: Unit 9viihaanghtrivediNo ratings yet

- 8 WebDocument4 pages8 WebAdarsh AshokanNo ratings yet

- Virtual MemoryDocument3 pagesVirtual MemoryaishaumairNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of A Program in MemoryDocument19 pagesAnatomy of A Program in MemoryVictor J. PerniaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Main Memory - Part IIDocument19 pagesChapter 8 - Main Memory - Part IIas ddadaNo ratings yet

- Part 1B, DR S.W. MooreDocument16 pagesPart 1B, DR S.W. MooreElliottRosenthal100% (3)

- Caches and Virtual Memory:-PlanDocument29 pagesCaches and Virtual Memory:-PlanHibban AjaNo ratings yet

- ICS 143 - Principles of Operating SystemsDocument83 pagesICS 143 - Principles of Operating SystemsManoj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Memory Management: Practice ExercisesDocument4 pagesMemory Management: Practice Exercisesankush ghoshNo ratings yet

- Slides Ch3 Memory ManagementDocument23 pagesSlides Ch3 Memory ManagementAbuky Ye AmanNo ratings yet

- Ch. 3 Lecture 1 - 3 PDFDocument83 pagesCh. 3 Lecture 1 - 3 PDFmikiasNo ratings yet

- CS433: Computer System Organization: Main Memory Virtual Memory Translation Lookaside BufferDocument41 pagesCS433: Computer System Organization: Main Memory Virtual Memory Translation Lookaside Bufferapi-19861548No ratings yet

- Lovely Professional University: Computer Organization and ArchitectureDocument7 pagesLovely Professional University: Computer Organization and ArchitectureYogesh Verma YogiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Virtual Memory p1Document33 pagesChapter 7 Virtual Memory p1ahmedibrahimghnnam012No ratings yet

- Unit-IV: Memory Allocation: SRM University, APDocument100 pagesUnit-IV: Memory Allocation: SRM University, APdinesh reddyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Virtual Memory Part-1Document33 pagesChapter 7 Virtual Memory Part-1Ahmed Ibrahim GhnnamNo ratings yet

- M2: Memory Management: Binding of Instructions and Data To MemoryDocument3 pagesM2: Memory Management: Binding of Instructions and Data To Memory왕JΔIRΩNo ratings yet

- MemoryDocument24 pagesMemoryshardoolgNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - Computer System Organisation - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inDocument8 pagesUnit 4 - Computer System Organisation - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inmukulgrd1No ratings yet

- Unit-3 Os NotesDocument33 pagesUnit-3 Os Noteslinren2005No ratings yet

- Virtual Memory (Computer Operating System)Document44 pagesVirtual Memory (Computer Operating System)Umera Anjum100% (1)

- Distributed Shared Memory: Introduction & ThisisDocument22 pagesDistributed Shared Memory: Introduction & ThisisSweta UmraoNo ratings yet

- Tukuran Technical - Vocational High School: Immediate Access Store, AlsoDocument2 pagesTukuran Technical - Vocational High School: Immediate Access Store, AlsoEfren TabuadaNo ratings yet

- Assignment: SUBJECT: Advanced Computer ArchitectureDocument7 pagesAssignment: SUBJECT: Advanced Computer ArchitectureAbhishemNo ratings yet

- CS1120 - Principles of Operating Systems: Lectures 10,11,12 And13 - Memory Management Mr. Rowan N. ElominaDocument83 pagesCS1120 - Principles of Operating Systems: Lectures 10,11,12 And13 - Memory Management Mr. Rowan N. ElominaMelvin LeyvaNo ratings yet

- OS Unit - 4 NotesDocument35 pagesOS Unit - 4 NoteshahahaNo ratings yet

- Memory ManagementDocument75 pagesMemory ManagementJong KookNo ratings yet

- Memory Management: Process Address SpaceDocument18 pagesMemory Management: Process Address Spaceyashika sarodeNo ratings yet

- Virtual and Cache Memory Implications For EnhancedDocument9 pagesVirtual and Cache Memory Implications For EnhancedSaurabh DiwanNo ratings yet

- Main MemoryDocument120 pagesMain MemoryPark DylanNo ratings yet

- Operating System - Memory Management: Process Address SpaceDocument21 pagesOperating System - Memory Management: Process Address SpaceMamathaNo ratings yet

- Distributed Shared MemoryDocument23 pagesDistributed Shared MemorySweta UmraoNo ratings yet

- Unit 06Document34 pagesUnit 06mukisa6ivanNo ratings yet

- Process Address Space: Memory ManagementDocument17 pagesProcess Address Space: Memory ManagementMohit SainiNo ratings yet

- Basics of Operating Systems: What Is An Operating System?Document4 pagesBasics of Operating Systems: What Is An Operating System?Mamta VarmaNo ratings yet

- Memory Management: Background Swapping Contiguous Allocation Paging Segmentation Segmentation With PagingDocument55 pagesMemory Management: Background Swapping Contiguous Allocation Paging Segmentation Segmentation With PagingsumipriyaaNo ratings yet

- Objectives: Johannes Plachy IT Services & Solutions © 1998,1999 Jplachy@jps - atDocument35 pagesObjectives: Johannes Plachy IT Services & Solutions © 1998,1999 Jplachy@jps - atwidgetdogNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document58 pagesUnit 3Subhash Chandra NallaNo ratings yet

- Lecture (Chapter 9)Document55 pagesLecture (Chapter 9)ekiholoNo ratings yet

- Unit 4-PagingDocument20 pagesUnit 4-PagingBarani KumarNo ratings yet

- December 2011 SolvedDocument9 pagesDecember 2011 Solvedchanchal royNo ratings yet

- 18CSC205J Operating Systems-Unit-4Document110 pages18CSC205J Operating Systems-Unit-4Darsh RawatNo ratings yet

- Computer Organization and Architecture Unit MemoryDocument22 pagesComputer Organization and Architecture Unit MemoryKUNAL YADAVNo ratings yet

- Multimedia Technologies & ApplicationsDocument20 pagesMultimedia Technologies & Applicationsking vjNo ratings yet

- Programming Languages and Their Translators: 6.1 Interpreters Versus Compilers 6.2 How Compilers Produce Machine CodeDocument22 pagesProgramming Languages and Their Translators: 6.1 Interpreters Versus Compilers 6.2 How Compilers Produce Machine CodeKMC NisaanNo ratings yet

- 4-0-1 Introduction To Microsoft Word Student ManualDocument9 pages4-0-1 Introduction To Microsoft Word Student ManualChristian AstreraNo ratings yet

- Accounting Principles and NotesDocument44 pagesAccounting Principles and NotesPickboy XlxlxNo ratings yet

- 2 8 Dedicated Computer Systems Student NotesDocument1 page2 8 Dedicated Computer Systems Student Notesking vjNo ratings yet

- Interrupts: 6.1 Examples and Alternate NamesDocument14 pagesInterrupts: 6.1 Examples and Alternate NamesAadhya JyothiradityaaNo ratings yet

- CPU Implementation: 5.1 Defining An Instruction SetDocument34 pagesCPU Implementation: 5.1 Defining An Instruction SetAadhya JyothiradityaaNo ratings yet

- Chapter7 PDFDocument12 pagesChapter7 PDFPochana Ram Kumar ReddyNo ratings yet

- The Memory Hierarchy (2) - The Cache: 8.1 Some ValuesDocument22 pagesThe Memory Hierarchy (2) - The Cache: 8.1 Some ValuesESSIM DANIEL EGBENo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document12 pagesChapter 9Ritapa DasNo ratings yet

- Fanuc 11T Configuration DocumentDocument2 pagesFanuc 11T Configuration DocumentLeonardusNo ratings yet

- 01 MS-1585 MS-17L5 v1.0 EnglishDocument68 pages01 MS-1585 MS-17L5 v1.0 EnglishAadee MalavadeNo ratings yet

- Mitsubishi PLC AnSH CPU Users ManualDocument242 pagesMitsubishi PLC AnSH CPU Users Manualvuitinhnhd9817No ratings yet

- BRKUCC-2011 Best Practices For Migrating Previous Versions of Cisco Unified Communications Manager (CUCM) To CUCM 8.6Document112 pagesBRKUCC-2011 Best Practices For Migrating Previous Versions of Cisco Unified Communications Manager (CUCM) To CUCM 8.6drineNo ratings yet

- Absolute Beginners Guide To The Intel EdisonDocument8 pagesAbsolute Beginners Guide To The Intel Edisonmarius_danila8736No ratings yet

- 5 PIC16F887 MicrocontrollerDocument40 pages5 PIC16F887 MicrocontrollerBalakumara Vigneshwaran100% (4)

- Computer Notes PDFDocument155 pagesComputer Notes PDFVeeresh HiremathNo ratings yet

- Cubeacon IBeacon Datasheet V 2.3Document9 pagesCubeacon IBeacon Datasheet V 2.3Arief BachrulNo ratings yet

- NIGIS PPP AgreementDocument15 pagesNIGIS PPP AgreementNasiru Abdullahi BabatsofoNo ratings yet

- Product Support For Factory Talk ActivationDocument2 pagesProduct Support For Factory Talk ActivationRachiahi TarikNo ratings yet

- CDKR Web v0.2rcDocument3 pagesCDKR Web v0.2rcAGUSTIN SEVERINONo ratings yet

- NORVI IIOT Getting Started V4Document1 pageNORVI IIOT Getting Started V4smartnaizllcNo ratings yet

- PC MP 4055Document325 pagesPC MP 4055Técnico EspecializadoNo ratings yet

- Edm Specifications 100Document124 pagesEdm Specifications 100Apc CamNo ratings yet

- Information and Communication Technology For SHS Part 1Document22 pagesInformation and Communication Technology For SHS Part 1Samuel Teyemensah Kubi100% (1)

- Simatic S7-300: The PLC For With As Focal PointDocument28 pagesSimatic S7-300: The PLC For With As Focal PointPrittam Kumar JenaNo ratings yet

- Part 2Document39 pagesPart 2Aschalew AyeleNo ratings yet

- Everfocus PTZ 1000 PDFDocument2 pagesEverfocus PTZ 1000 PDFShannonNo ratings yet

- Computer Fundamentals - Aditya RajDocument20 pagesComputer Fundamentals - Aditya Rajanant rajNo ratings yet

- Exp4-Add, Sub, Mul, Div of 8 Bit & 16 BitDocument6 pagesExp4-Add, Sub, Mul, Div of 8 Bit & 16 Bitjinto0007No ratings yet

- ETPMDocument11 pagesETPMsamiie30No ratings yet

- Multifunctional Bench Scale For Standard Industrial ApplicationsDocument4 pagesMultifunctional Bench Scale For Standard Industrial ApplicationsHector Fabio Carabali HerreraNo ratings yet

- TI C2000™ MCU Digital Power Selection GuideDocument3 pagesTI C2000™ MCU Digital Power Selection GuidemanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter Cdk3-18: Mach Case StudyDocument18 pagesChapter Cdk3-18: Mach Case StudyAndrea BatesNo ratings yet

- 088 S 12 - Technical Info ACE Automatic Computerized OedometerDocument4 pages088 S 12 - Technical Info ACE Automatic Computerized OedometerDom MonyNo ratings yet

- PLC m1Document11 pagesPLC m1Goutham KNo ratings yet

- Samsung SPC-10: HMI SettingDocument3 pagesSamsung SPC-10: HMI SettingJubaer KhanNo ratings yet

- QUESTION: Explain The Classification of ComputerDocument6 pagesQUESTION: Explain The Classification of ComputerJohn JamesNo ratings yet