Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Onlinelegalinformationsystem Cambridge

Uploaded by

kumar kartikeyaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Onlinelegalinformationsystem Cambridge

Uploaded by

kumar kartikeyaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/259423354

Online Legal Information Systems in India: a Case Study from the Faculty of

Law, University of Delhi

Article in Legal Information Management · June 2012

DOI: 10.1017/S1472669612000357

CITATIONS READS

8 5,472

1 author:

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

St. Stephens College

47 PUBLICATIONS 248 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Online Legal Information System (OLIS), accessible at: http://www.olisindia.in View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Raj Kumar Bhardwaj on 18 August 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Legal Information Management

http://journals.cambridge.org/LIM

Additional services for Legal Information Management:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Online Legal Information Systems in India: a Case Study from the Faculty

of Law, University of Delhi

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

Legal Information Management / Volume 12 / Issue 02 / June 2012, pp 137 - 150

DOI: 10.1017/S1472669612000357, Published online: 08 June 2012

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1472669612000357

How to cite this article:

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj (2012). Online Legal Information Systems in India: a Case Study from the Faculty of Law, University of

Delhi. Legal Information Management, 12, pp 137-150 doi:10.1017/S1472669612000357

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/LIM, IP address: 14.139.45.244 on 06 Jun 2014

Legal Information Management, 12 (2012), pp. 137–150

© The Author(s) 2012. Published by British and Irish Association of Law Librarians doi:10.1017/S1472669612000357

Online Legal Information Systems

in India: a Case Study from the

Faculty of Law, University of Delhi

Abstract: In this digital age, users require immediate access to information. To foster

the process of research, the legal fraternity demands efficient online legal information

systems. Raj Kumar Bhardwaj provides a view from India and reports on a case study that

has been conducted on the use of various legal information databases in the Faculty of

Law, University of Delhi, India. In his paper, he also reviews and discusses the various

aspects relating to legal information retrieval systems, with particular reference to the

various essential legal databases that cover Indian law.

Keywords: legal databases; information retrieval; India

INTRODUCTION searchers making fewer errors, or being

able to recover from more errors. Yuan

Naturally, the main aim of legal infor- also found that although participants with

mation retrieval systems is to find higher levels of quick law experience used a

relevant documents in relation to greater variety of commands and features

the search query as defined by the than those with lower levels of experience,

user. Major litigation consists of some commands remained rarely or never

three stages – pre-trial, trial and used.

appeal; but information sought by Oulanov and Pajarillo (2003)2 also con-

the litigant is similar in nature at ducted a study on perceptions of

each stage. The pre-trial stage LexisNexis, this time using structured

involves intensive document discov- questionnaires that were issued to eight aca-

ery while in the trial stage the main demic librarians at Queens Borough

focus is on providing fast retrieval, Raj Kumar Bhardwaj Community College in New York City.

and tracking, of various documents that have been intro- Although the authors did not include a copy of the ques-

duced in evidence. At the appeal stage the main focus is tionnaire used, the tables that were included reveal that the

on trial and case law. In the digital era various search questionnaire was predominantly based on a five point

techniques are used to explore the legal databases and Likert grading scale aimed at uncovering the librarians’ per-

these are different from other conventional search ceptions on three aspects of the resource; its ‘retrieval fea-

techniques. tures’; its ‘effectiveness’ and other usability-related aspects

which the authors rather ambiguously categorise under the

heading ‘user effort perception criterion’.

SEARCHING LEGAL DATABASES: Komlodi and Soergel (2002)3 also focused on infor-

mation use and re-use, specifically on legal information

SOME THEORY AND A LITERATURE

seekers and the use of their memory and externally

REVIEW recorded search histories to inform their later searches.

Yuan (1997)1 monitored the LexisNexis quick law searches Komlodi and Soergel found, like Kuhlthau and Tama

of a group of law students over a period of one year. Yuan (2001)4 and Blomberg et al. (1996)5, that during the legal

examined several aspects of their searching behaviour, research process, law students not only needed to

including the increase of their command and feature reper- consult electronic legal resources, but also needed to

toires, their change in language usage, the increase of return to their personal research files. Komlodi and

search speed and the change of learning approaches. Yuan Soergel developed a set of search-history-based user inter-

discovered that experience did not result in either face tools to support the recording, categorisation and

137

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

annotation of search results. These were achieved by the

system keeping track of user actions and results, and

using this expanded history to encourage easier infor-

mation re-use and future search tasks. The work led to a

form of search histories being incorporated into the

Westlaw electronic legal resource.

Marshall et al. (2001)6 conducted a study and ident-

ified the continued importance and authority of books in

students’ legal research process. The study found that

many of the users’ information-seeking strategies fol-

lowed links rather than conducting explicit searches and

highlighted the use of electronic resources for case evalu-

ation. Marshall et al. stated in their study that students

began their moot court research by identifying case law

and described this as a ‘launching pad’ or ‘looking for a

thread to pull!’ The students then continued to use cita-

tions as a point of departure, either as obvious links to a

precedent if they came across the citation several times

or as a way of determining whether the cases were still

‘good law’.

Figure 1: Legal search strategies

Essential Search techniques

In legal text searching a Natural Language Query is one

Coverage of Collection

that is expressed using normal conversational syntax. The

benefits of using natural language queries are that it can Typically, legal databases contain case law of various High

take less time than traditional Boolean queries. Courts and Supreme Courts; and articles published in

Fuzzy words can be used in the feedback searching journals together with speeches of eminent personalities

process to gain added insight into the nature of databases. from the legal fraternity.

The fuzzy operator scans the database for words with a

spelling similar to that of a query term. It can recognise

incorrect spelling and instances where scanned materials Recall

have been incorrectly integrated during the Optical Recall is the ratio of the number of relevant records

Character Recognition (OCR) process. Fuzzy matching retrieved compared to the total number of relevant

looks for words that are similarly spelt in the database. records in the database.

Operators can be helpful in finding word variants or mis-

spellings in the database, the result of typographically

mistakes or errors during the process of OCR. Precision

Precision is the ratio of the number of relevant records

LEGAL SEARCH STRATEGIES AND retrieved compared to the total number of irrelevant and

RETRIEVAL SYSTEMS relevant records retrieved.

The components of legal text retrieval systems

can be categorised in the following way: Fall-out

a. Text-file Search; The term, fall-out, refers to all the ‘junk’ received from

b. Discarded stop words; the search that is irrelevant. If 100 documents are

c. Index to search file; retrieved and 20 are relevant, then fallout is 80%. Fallout

d. Interest retrieval; becomes a larger issue as the size of the database grows.

e. Fact Retrieval;

f. Coverage of collection;

g. Speed of retrieval; Presentation of results

h. Recall of system;

In most cases the results that are displayed are for-

i. Precision of system; matted as a vertical list of retrieved documents. An item

j. User friendliness. in the displayed list consists of the title of the document

The six qualities of information retrieval and a set of important metadata such as the party

systems, as listed by Cyril Cleverdon in his evaluation of name, the advocate, the name of the judge and the date

information retrieval,7 are: of decision, along with a headnote of the case.

138

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Online Legal Information Systems in India

Time and effort involved to obtain ELECTRONIC LEGAL DATABASES

answers Naturally, in India as eleswehere, electronic databases

The time and effort involved in the process to retrieve play a major role in libraries. In order to fulfill the individ-

the relevant records should be minimal and it should be ual and varied needs of their users, law libraries subscribe

user-friendly so that users can access the system without to a host of electronic services. Indian law libraries sub-

any constraints (Kumar et al. 2005).8 scribe to, and make significant use of, the following data-

bases – HeinOnline, Westlaw, Manupatra, Grand Jurix,

SCC online, A.I.R Online, and Lexis. Two services, of par-

ticular value, among Indian law libraries are Westlaw,

PERFORMANCE OF TEXT RETRIEVAL

which gives access to more than 4,500 international

There is a significant difference between interest and online journals, and Hein Online, which provide access to

fact retrieval. Lawyers use fact retrieval for mainly more than 1,500 journals.

three purposes; i) to find dates, either within the docu- The databases listed above each provide a range of

ments or as part of the identification of a document facilities by which numerous operators can be used to

ii) lawyers search for document identifications, names, retrieve relevant case law. A review of these services and

cases, citation of statutes iii) to look for party names, their retrieval systems is provided below.

name of advocates, name of judges, and so forth.

In fact, the retrieval of documents is designed so that

the date of the case and the text of the case itself has the COMMERCIAL LEGAL INFORMATION

same weightage. Failures to retrieve documents are inter- SYSTEMS: A SYNOPSIS

preted as precious information provided that there are no

SCC Online Case Finder

errors in the material; denoting that there is no citation

to the case in question. Interest retrieval is characterised The SCC (Supreme Court Cases) Online Case Finder is

by a difference in the assessment of relevance as it is not a proprietary product of EBC Publishing Pvt. Ltd based in

possible to specify which relevant text a particular docu- Lucknow, INDIA. It has an installation of two CD-ROMs

ment contains. (a) Typical Mode (b) Minimal Mode (Figure 2).

Figure 2: SCC Online Case Finder

139

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

The ‘Search Results’ dialog box contains separate LexisNexis India

lists of the case-notes found for each database (modes 1

and 2) that is searched. They are alphabetically arranged LexisNexis is the product division of Reed Elsevier India

by the topic/statute headings under which they occurred. Pvt. Ltd. It covers all Supreme Court Cases (since incep-

For judgments, the sorting order is by the date of the tion), updated legal acts and articles from selected legal

decision of the case and the first few case-note headings journals. There are also new editions of commentaries by

are displayed on the screen. Typically, the total number eminent legal authors. It has a helpful my book shelf facility

of case-notes found can often exceed the number of and, in terms of search opportunities, users can search

case-notes that can be displayed in the visible portion of all the resources from the home page. The way that the

the list. results are clustered empowers the user with multi-

faceted hits for each result. Controlled vocabulary is used

in the indexing of the database. The taxonomy refers to

the topic level of classification of chapters (Figure 4).

All India Reporter(AIR) on CD-ROM

Legal Pundits

This database offers full text judgments of the

Supreme Courts of India and all High Courts. It gives This legal database was created by Legal Pundit

the headnotes, citation search, free text search, search International Service Pvt. Ltd. with the aim of delivering a

by party name, the name of the judge and statutes gamut of legal information services to individuals and

name, and so on. The advanced query also gives com- enterprises. It empowers users with both a general

plete access to the Folio Views Query Syntax. This search and a case law search facility. The database covers

syntax helps to focus and refine searches through the the cases from the Supreme Court, various High Courts,

use of Boolean operators, wildcards, proximity oper- APTEL, AAR, CAT, Company Law Board, DRAT, DRT,

ators and scope limitations. The Query option gives CERC, IPAB, ITAT, NCDRC, Privy Council, SCDRC, SEBI

more information about performing simple searches (SAT), STT, TDSAT, Trademark and can be searched by

(Figure 3). various subjects areas9. However, the general search

Figure 3: SCC Online Case Finder – search screen

140

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Online Legal Information Systems in India

Figure 4: LexisNexis India

option allows the search to be expanded to commen-

Chawla Law Finder

taries and analysis, notifications, forms and procedures, Chawla Law Finder is an efficient, time saving and an

circulars, rules, guidelines, schemes, drafts, bare acts, economical case search engine designed and developed

trade notices, press notes, regulations, policies, and so by Chawla Publication Pvt. Ltd. The case finder contains

forth (Figure 5). five databases; (a) Recent Criminal Reports (b) Recent

Searches can be saved, draft searches can be viewed Civil Reports (c) Service Cases Today (d) Recent Control

and the case law search archive can be checked. Reporter (e) Dishonour of Cheques Total Cases.

Figure 5: Legal Pundits.com

141

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

Judgments can be searched with the court name, judge Manupatra

name, decision date, petitioner, respondents, advocate

name, head-note, and case reference order and result. This Online Manupatra.com was launched in the year 2001

case finder gives the user advanced search features such as with a wide variety of content – i.e. commentaries,

feedback search, concept searching and fuzzy words. digest, editorial enhancements, treaties, case laws and

more. It empowers its user with legislative and pro-

cedural information. It covers Supreme Court Cases

Grandjurix from 1950 to date, cases from the high courts, tribunals

Grandjurix is available in CD-ROM format as well as an and commissions. It also contains acts, notifications and

online product. The electronic version is called e-Jurix, a circulars, forms, draft agreements, WTO, materials relat-

product of Spectrum Business Support Ltd which was ing to arbitration, cyber laws, intellectual property law,

established in 1988. It covers 250,000 full text judgments labour and employment law, human rights, environmental

and covers all Supreme Court, High Court and Tribunal law, and media and communication laws.

Decisions reported to date. eJurix provides search facilities In addition, Manupatra gives access to e-books, elec-

by full text, subject, section-act, title, keywords phrases, sta- tronic articles and has an international aspect to the data-

tutes referred, quorum of judges, name of the court, date base too. It has a facility for equalling citations of multiple

of decisions, and equivalent citations. It also includes the print journals. Efficient hyperlinks, to referred judgments,

full text of judgments of appropriate quasi-judicial bodies, assist the legal researcher. Overruled and reversed judg-

High Courts and the Supreme Court of India, from 1950, ments can also be identified in Manuptra. Each section

as well as basic Information – acts rules and regulations, within the judgments is hyperlinked so that researchers

and notifications & circulars issued by the Law can access the bare acts instantly. Searches can also be

Enforcement agencies. eJurix has a personalisation facility achieved with the citation, i.e. volume no, year, page no.,

which allows the user to store expertise and save the etc. More than 1,100 bare acts are regularly added

search terms in the database (Figure 6). which includes various amendments and repealed acts

The My preferences option in the side bar assists the (Figure 8).

user to set the search settings; it helps users to search

the title, the contents and the annotations. Proximity

options extend the facility to search anywhere – i.e. a THE OPERATORS USED IN LEGAL

phrase search, search within a sentence, search within a TEXT RETRIEVAL: A REAPPRAISAL

paragraph and to search with up to 40 words. Acts, rules

and notifications can be searched as well as be browsed

Single Character wildcard operator

alphabetically. The advanced search feature makes it In search retrieval, the single character wildcard, i.e. the

more robust. Users can select court name, judge name question mark, is used to represent a single variable char-

and year of judgment. The volume number and page can acter in a given query; eg. the syntax would be Str??ing for

also be searched (Figure 7). string; Exclu???? will find excluding, exclusive.

Figure 6: eJurix

142

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Online Legal Information Systems in India

Figure 7: eJurix – Case law searching

In single character wildcard searching, another option query will find the terms like color and colour. The

is matching one, or more, characters; employing the second query will search for terms like VTOL, VSTOL.

optional wildcard which represents one, or more, variable The third query would search for terms like electron,

characters. Egs. Colo$r, V$TOL, Electron$$$. The first electrons, electronic and electronics.

Figure 8: Manupatra

143

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

Matching a character string; the asterisk represents an ordered proximity search must be enclosed in quotes.

a variable string of one or more characters in a query. The As a side note, a phrase search is, basically, an ordered

string wildcard is equivalent to an infinite series of adjacent proximity search with a proximity equal to the number of

optional character wildcards. Examples: Medic*, m*n. The terms in the phrase. e.g. “Court constitution”/5. This

first search term will search for media, medical, medicine, means find records which contains ‘court’ and ‘consti-

medicate, medically, medication, and second will search tution’ in that order, within a 5 words range. While unor-

man, men, mean, moon and moron! dered proximity is to specify a set of terms which must

appear within a given range in any order. The unordered

proximity operator is the @ symbol. Terms in an unor-

The Fuzzy search operator

dered proximity search word must be enclosed in quotes.

The fuzzy search operator is used to retrieve records that

contain words with spellings similar to that of a particular

Adjacency Operator

query term. That part of a query term will be matched

exactly as determined by the placement of the operator This operator is equivalent to the proximity operator with

within the word. The character string that precedes the a defined range of one word. Certain punctuation –

operator will be anchored eg. Rajn ~ h, Corr ~ o. The hyphens, apostrophes, commas and periods- function as

first query will retrieve record that contains Rajnish, or adjacency operators when they appear in the middle of

alternate spellings of the word Rajneesh and second character string. This operator does not work across field

query will retrieve records that contain corrode, or simi- boundaries and this is unidirectional from left to right.

larly spelled words like corrosive and corrosion.

Same/n operator

Concept Operator

This operator is a search query term that is within n

The concept search operator retrieves results on the basis paragraphs of another query term. A law finder will auto-

of concept and many results will be retrieved that do not matically search for documents in which query terms on

having the occurrences of the original query word. either side of the same operator appear in the same

paragraph. The same operator is bidirectional, eg. poison

same/3 Chandigarh.

Near Operator

This operator searches for word pairs in which the

Not same operator

second term occurs within the specified number of

words before, or after, the first. It is a bidirectional The Not same operator searches for query terms that do

proximity operator and works across boundaries; you not appear in the same paragraph as the second query term.

cannot use it to search for a word pair in which the In addition this operator is unidirectional, eg. poison not

words occupy separate places within a record. This is same dowry. The query will retrieve documents in which

a search operator that is evident in the Chawla Law poison does not fall in the same paragraphs as dowry.

Finder database.

At least /in operator

Boolean Operator

This operator is used to search records that contain

The commonly used And, Or, Not operators are often occurrences of the query expression that immediately

used to define the relationship between a party name, follows the at least operator. Eg. at least /10 soldiers will

judge name, case number, court name, keywords or search at least 10 occurrences of the word, soldiers.

group. With the help of these operators, combinations of

elements can be searched.

Exact Match

The exact match search for an individual query uses a

Proximity operator

sign to force a search for the exact word only. Eg.

This operator is used to search for word pairs in which “India”. This query will search only India and not Indian

the second term of the pair occurs within a specified or Indiana.

number of words after the first. This operators does not

work across field boundaries and it cannot be used to

Exact phrase operator

search for word pairs in which the word occupys separate

fields within the record. Proximity operators can be The exact phrase operator – the single quotation mark –

further classified as the (a) Order Proximity search and combines characteristics of the adjacency and exact

(b) Unordered Proximity search. Order Proximity is used match operators; with this operator we can search exact

to specify which term must appear within a given range to matches of a phrase such as; “code of criminal

count as a hit. This is used with a forward slash. Terms in procedure.”

144

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Online Legal Information Systems in India

Equivalence operator lower occur in the decision date field. The second will

retrieve the record in which the name field contains

This operator is used to search records containing the values alphabetically between Mahesh and Ramesh.

specified alphanumeric value in the specified field (or

series of fields specified by commas), eg.; Judge = Gaur

and Gaur = Judge; both options search for judgments Query level field restriction operator

containing Gaur in the Judge field.

This operator searches for records in which the query

terms preceding it appear in the field (or series of fields

Range Operator separated by commas) that follows it.

With this operator, we can search for records in which a

specified field contains the specified value. The syntax

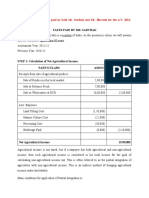

Legal Databases and their Search Features

of this operator is an angle bracket greater (>) than and

less than equal (<) bracket followed by the equal sign (>=, The table below offers a comparison of the operators

<=). Example: Decision date <= 1990, Mahesh < and search features (as described in the text above)

Petitioner < Ramesh. In the above example, the first between various key legal databases used by researchers

query will retrieve record in which value of 1990, or and scholars in relation to Indian law.

Comparative study of various search operators and search features used in legal databases

Techniques Availability SCC Online A.I.R Manupatra Grandjurix Chwala

Boolean Operator Y Y Y Y Y

Concept Operator Y N Y N Y

Fuzzy search Operator Y N Y N Y

Proximity Operator Y Y Y Y Y

String Wildcard Operator N Y Y N Y

Adjacency Operator Y N N Y N

Same/n operator N Y Y Y

Not same operator N N N N Y

Equivalence Operator Y N N N N

Range Operator Y Y Y Y Y

Query level field restriction operator Y N Y N Y

Exact phrase operator Y Y Y Y Y

At least /in operator N N N N Y

Optional Character wildcard operator Y Y Y Y Y

Search within search Y N Y Y Y

Citation Search Y N N Y Y

Over ruled judgments Y N Y N Y

Further referred Judgments Y Y Y Y Y

Head note search Y Y N N N

CASE STUDY OF FACULTY OF LAW, (a)to study the awareness, use and the method of using

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI, DELHI the legal information databases among library users;

Objectives of the Study: (b)to study the frequency and purpose of using legal

The following objectives were set up for the Study: information databases;

145

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

(c)to identify the search method used in searching legal respondents were unaware of the legal information

information databases; databases.

(d)identify the method of training to use the legal

information systems in a training programme;

Frequency of Use

Users were asked to mention the frequency of the usage

(e)to rate the quality of legal information databases. of electronic resources with four options-frequently,

occasionally, sometime and rarely. 30% of the LLB

respondents indicated they frequently used the electronic

resources. 40% respondents replied that they occasionally

Methodology and Analysis of Data: used these and 20% stated sometime, However 6%

In order to know the true usage of electronic infor- respondents rarely used the electronic resources while

mation sources, a survey was conducted in 2011 and 4% respondents stated that they never used the legal

a questionnaire was prepared to collect the data. A total information databases. The table shows the slight differ-

of 139 questionnaires were distributed and 66.18% com- ence in frequency of usage of Legal Information Database

pleted questionnaires were received. between LLB and LLM students.

Awareness about Legal Information Purpose of Using Legal Information

Databases Databases

Table 1 summarises the awareness of electronic Within the questionnaire respondents were asked about

resources and shows that 66% of the LLB respondents the purpose of using electronic resources, using open

were aware of the electronic databases, whereas only ended questions, six reasons were enlisted with more

34% respondents indicated they were unaware. than one option of choice. 21.34% of the respondents

However, LLM students (95%) were more aware; only used legal information databases in research and develop-

5% stated they were unaware of electronic legal data- ment activities with 33.70% using them for projects and

bases. Overall, 78.89% of the respondents were aware of assignments. 33.70% respondents were in support of case

legal information database; however 21.11% of the law searching. As far as the purpose of using e-resources

Table 1 – Awareness of Legal Information Database

Awareness of electronic resources LL.B % LL.M % Total

N = 50 N = 40

Yes 33 66% 38 95% (78.89%)

No 17 34% 2 5% (21.11%)

Note: n = 90

Table 2 – Frequency of using online Legal Information Database by LLB and LLM students

Frequency of use LLB % LLM % Total

N = 50 N = 42

Frequently 15 30% 30 71.42% (48.91%)

Occasionally 20 40% 4 9.52% (26.08%)

Sometime 10 20% 5 11.90% (16.30%)

Rarely 3 6% 2 4.76% (5.43%)

Never 2 4% 1 2.38% (3.26%)

Note: n = 92

146

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Online Legal Information Systems in India

Table 3 – Purpose of using Legal Information Database by LLB and LLM students

Purpose of using e-resources LLB % LLM % Total

N = 49 N = 40

Case Law Searching 10 20.40% 20 50% (33.70%)

Study and Update 5 10.20% 5 12.5% (11.23%)

R & Development Activities 9 18.36% 10 25% (21.34%)

Project & Assignments 25 51.02% 5 12.5% (33.70%)

Teaching & lectures – – – – (%)

Any other – – – – –

Note: n = 89

in different disciplines was concerned, 11.23 % of law stu- help of library staff. Only 5.43% of respondents stated

dents used them for study and update purpose. they learnt the use of e-resources by trial and error.

Search and Retrieval Rating the Quality of Legal

Information Database

The data depicted below in Table 4 explains that respon-

dents preferred boolean operators in their search and The survey listed ten types of e-resources and respon-

retrieval. While 91.30% of the respondents preferred the dents were asked to rate the quality as available through

simple search, interestingly, 84.78% of the respondents the library portal. Four options were given: excellent,

opted for the boolean search method. None of the very good, good and poor. Table 6 shows that the

respondents selected the command level search and retrie- majority of respondents agreed that the quality of

val. Where the proximity search was concerned only resources are excellent.

23.91% of the respondents stated they used this method

for searching and retrieval and 76.08% mentioned the use

of the wild card search. It is perhaps surprising that 71.91%

Training for Using of Legal

of LLB students used the wild cards while 54.16% used Information Databases

truncation. The data revealed that the majority of law faculty

members – i.e. 51.68% – needed training to use journal

portals, while 48.38% replied that they did not require

Method of Learning

any training to use e-resources. 61.22% of LLB students

In order to more fully understand the methods of using responded that they needed training, while 51.61% of

e-resources, users were provided with five options; i.e. LLM students requested training in order to learn the

workshops, tutorials, a printed manual, one-to-one necessary skills to use legal information systems. When

tuition or any other method. The table below shows that asked to respond about the various methods of training,

48.91% of the respondents learnt by their own, while Table 7b indicates that 43.75% stated that the tutorial

32.60% learnt with the help of friends or colleagues; method should be the adopted approach for legal infor-

13.04% of the respondents stated they learned with the mation database training whilst 14.53% thought that the

Table 4 – Search and Retrieval method used in Legal Information System

Menu Driven Search LLB % LLM % Total

N = 48 N = 44

Wild cards 35 71.91% 35 79.54 (76.08%)

Selectable truncation 26 54.16% 12 27.27 (86.36%)

Boolean operator 40 83.33% 38 86.36 (84.78%)

Proximity function 10 10% 12 27.27 (23.91%)

Simple search in all field 40 83.33% 44 100% (91.30%)

Command language interface – – – – –

Note: n = 92

147

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj

Table 5 – Method of using e-Resources LLB and LLM students

Method of learning LL.B % LL.M % Total

N = 49 N = 43

Own Learning 20 40.81% 25 51.02% (48.91%)

With the help of friend or colleague 15 30.61% 15 34.88% (32.60%)

Help of Library staff 10 20.40% 2 23.25% (13.04%)

Trial and error 4 8.16% 1 2.32% (5.43%)

Any other — –

Note: n = 92

Table 6 – Rating the Quality of Information Database by LLB and LLM students

Legal information Systems N Excellent Very Good Good Poor

Supreme Court Case Finder 70 50 20 20 –

Grandjurix 72 20 20 32

Manupatra 60 25 24 20 (%)

Legal Pundit 64 24 24 16 –

Chawala CD-ROMs 60 25 20 15

AIR Online 63 18 18 37

Others (if any) – – – – –

Note: Respondents were asked to tick multiple options in the questionnaire.

Table 7(a) – Training to use Legal Information Database by LLB and LLM students

Training required LLB students % LLM students % Total

n = 49 n = 44

Yes 30 61.22% 18 40.90% (51.61%)

No 19 38.77% 26 59.09% (48.38 %)

Note: n = 93

lecture method was preferable. 41.66% responded that

Table 7(b) – Mode of Training of using Legal the workshop method should be used.

Information Database

Mode LLB and LLM students Total

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION

(n = 48)

In the digital age, documents pertaining to law, available

Lecture 7 14.53% in electronic form, are critical to legal research.

Workshop 20 41.66% Electronic retrieval of legal material facilitates the process

Tutorial 21 43.75% of legal objective research. Law libraries have a difficult

One to one – task to satisfy their stake holders in terms of legal

Printed – research with online legal information systems. The case

Manual study conducted in University of Delhi found that many

Note: n = 48 students, particularly the LLB students, are aware of the

range of electronic legal information services in the

148

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Online Legal Information Systems in India

library but that many are not full conversant with their of the users preferred the simple search method and the

usage. The study also reveals that 33.70% of the respon- boolean operators. Only expert users preferred the wild

dents use these online databases for case law searching, card and other proximity operators. Nearly half of the

while only 21.34 for research and development activities. respondents revealed that they used these resources by

Only 11.23% of respondents stated they used these data- ‘own learning’ and nearly 32.60% stated that they learned

bases for their studies and for updating their legal with the help of friends. A large number of respondents

research. As far as frequency of usage was concerned, desired to have appropriate training in order to learn the

only 48% used these legal databases. 26.02% of the use of the databases. It is clear that library and infor-

respondents used these resources occasionally while only mation professionals in India, as everywhere, play a major

16.30% stated they used them sometime. As far as search role in increasing the usage electronic services to expe-

and retrieval in database searching was concerned, most dite the process of legal research.

Footnotes

1

Yuan, W. “End-user Searching Behavior in Information Retrieval: A Longitudinal Study.” JASIST, (1997): 218–34

2

Oulanov, A., and E. Pajarillo. “Academic Librarians’ Perception of LexisNexis.” The Electronic Library 21.2 (2003): 123–29

3

Komlodi, A., and D. Soergel. “Attorneys Interacting with Legal Information Systems: Tools.” The 65th Annual Meeting of American

Society for Information Science and Technology. Philadelphia,USA, (2002): 152–63

4

Kuhlthau, C., and S. Tama. “Information Search Process of Lawyers: A Call for ‘Just for.” Journal of Documentation, 57.1 (2001):

25–43. Print.

5

Blomberg J., L. Suchman, and R. Trigg. “Reflections on a Work-oriented Design Project.” Human-computer Interaction, 11 (1996):

237–65

6

Marshall, C., M. Price, G. Golovchinsky, and B. Schilit. “Designing E-Books for Legal.” 1st ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital

Libraries. Virginia, Virginia. Virginia: Roanke (2001): 41–48

7

Cleverdon, C. The Evaluation of Systems used in Information Retrieval in Proceedings of the International Conference on

Scientific Information, Washington D.C. November 16–21, 1958. Vol 1. 687–698

8

Rakesh Kumar; Suri, P.K; Chauhan, R.K. (2005) Search Engines Evaluation Search Engines Evaluation, Desidoc Bulletin of Information

Technology, Vol. 25, No 2, March, pp 3–10

9

APTEL – Appellate Tribunal for Electricity

AAR – Authority for Advance Rulings

CAT – Central Administrative Tribunal

DRAT – Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal

DRT – Debt Recovery Tribunal, India

CERC – Central Electricity Regulatory Commission

IPAB – Intellectual Property Appellate Board

ITAT – Income Tax Appellate Tribunal

NCDRC – National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission – New Delhi

SCDRC – State Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission

SEBI(SAT) – Securities and Exchange Board of India (Securities Appellate Tribunal)

STT – Securities Transaction Tax (STT) Tax India

TDSAT – Telecom Disputes Settlement & Appellate Tribunal

Bibliography

Andrews, C. (1973) User Perceptions of CALR. Thesis. City University, London.

Bhardwaj, R. K. (2008) “Legal Information System in Digital Age.” Journal of Library and Information Science, 33, 93–100

Bhardwaj, (Raj Kumar) (2008). Legal Information System in Digital Era, Journal of Library and Information Science,

Vol. 33, 93–100

Borgman, C. (1988) “The User’s Mental Model of an Information Retrieval System.” International Journal of Man-

Machine Studies, 47–64

Callister, P.D. (2003) “Beyond Training: Law Librarianship’s Quest for the Pedagogy of Legal Research Education.”

Law Library Journal, 95.1, 7–45

“Centred Interactive Search with Digital Libraries Project Page.” Web. http://www.uclic.ucl.ac.uk/annb/DLUsability/

UCIS.html. [Accessed on: 2-8-2011].

Cheatle, E. (1992) “Information Needs of Solicitors.” Diss. City University, London (UK).

Elliott, M., and R. Kling. (1996) “Organizational Usability of Digital Libraries in the Courts.” 29th Annual Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences. Hawaii, 62–71

149

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

Current Awareness

Elliott, M., and R. Kling. (1997) “Usability of Digital Libraries: Case Study of Legal Research in Civil and.” JASIS,

48.11, 1023–035

Hainsworth, M. (1992) “Information-seeking Behaviour of Judges.” Thesis. Florida State University, USA, 1992. Print.

Howland, J.S. (1990) “The Effectiveness of Law School Legal Research Training Programs.” Journal of Legal Education,

40.1, 381–91

Jansen, B.J, Spink, A, & Saracevic, T. (2000) Real life, real users and real needs: A study and analysis of users’ queries

on the web. Information Processing and Management, 2000, 36, 207–27

Kidd, D. (1978) Legal Information of Solicitors in Private Practice. Diss. University of Edinburgh, UK.

Rosson, M., and J. Carroll. (2000) “Scenario-based Design .”The Human-compute Interaction Handbook. Ed. J. Jacko

and A. Sears. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1032–1050

Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research. London: Sage, 10–12

Vollaro, A., and D. Hawkins. (1986) “End-user Searching in a Large Library Network: A Case Study of Patent

Attorneys.” Online, 10.4, 67–72

Vyas, (S.D). (2010) Role of Academic Law Libraries with special reference to NALSAR University of Law Library,

Hyderabad. Library Herald, Vol. 48, No 1, March, pp 12–24

Biography

Raj Kumar Bhardwaj is currently working as College Librarian in St. Stephen’s College –Delhi (India). Prior to this,

he worked at the Judges Library, High Court of Punjab and Haryana (Chandigarh) and S.D.College (Ambala Cantt.).

He holds Master in Computer Application (MCA), M.L.I.Sc & an M.Phil in Library and information Science. He is

now pursuing Ph.D in Legal Information System. He has written many research papers in various journals and

spoken at international conferences. E-mail: raajchd@gmail.com

Legal Information Management, 12 (2012), pp. 150–154

© The Author(s) 2012. Published by British and Irish Association of Law Librarians doi:10.1017/S1472669612000369

Current Awareness

Compiled by Katherine Read and Laura Griffiths at the Institute of Advanced

Legal Studies

Holmes (Nick) & Venables (Delia) Who owns copyright in

This Current Awareness column, and previous Current judgments? Internet Newsletter for Lawyers. March/April

Awareness columns, are fully searchable in the caLIM data- 2012. pp.10–11.

base (Current Awareness for Legal Information

Managers). The caLIM database is available on the Perri (Kaitlin) Canadian copyright reform: Bill C-32 and effects

Institute of Advanced Legal Studies website at: http://ials. on legal library services. Canadian Law Library Review.

sas.ac.uk/library/caware/caware.htm Vol. 36, no. 4, 2011. pp. 168–171.

Rauer (Nils) Der elektronische Leseplatz, der Richterstuhl und

CATALOGUING AND CLASSIFICATION

der dritte Korb. Recht Bibliothek Dokumentation. Vol. 40,

Richards (Robert) The use of Non-MARC metadata in AALL no. 2/3, 2010. pp. 90–139.

libraries: a baseline study. Law Library Journal. Vol. 103,

no. 4, 2011. pp. 631–658. Stokes (Simon) Art and Copyright. (2nd ed). Oxford: Hart

Publishing, 2012. 306pp. £35. ISBN 9781849461627.

COPYRIGHT

DICTIONARIES

Davey (Francis) Does the Digital Economy Act 2010 have a

future? Computers & Law. Vol. 22, no. 6, Feb/March 2012. Kim-Prieto (Dennis) & Laer (Conrad J.P. Van) The possible

pp. 18–20. dream: perfecting bilingual law dictionaries by

150

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 06 Jun 2014 IP address: 14.139.45.244

View publication stats

You might also like

- Legal Memo (Writing Sample)Document14 pagesLegal Memo (Writing Sample)shausoon100% (4)

- A Recommendation System For Legal Semantic Web: AbstractDocument9 pagesA Recommendation System For Legal Semantic Web: AbstractInternational Journal of Engineering and TechniquesNo ratings yet

- Indexing and Abstracting Reviewer LLEDocument46 pagesIndexing and Abstracting Reviewer LLEYnna Pidor100% (1)

- Legal Research - Dr. AneeshDocument21 pagesLegal Research - Dr. AneeshPriyesh Kumar100% (1)

- Legal Research Use of Techniques Tools and Evolving TechnologyDocument17 pagesLegal Research Use of Techniques Tools and Evolving Technologysanjeev singh100% (1)

- Contract To SellDocument2 pagesContract To SellCharitoNo ratings yet

- JurimetricsDocument19 pagesJurimetricsmohit agarwalNo ratings yet

- ICC Moot Court Competition (International Rounds: Finalists) : Prosecution MemorialDocument46 pagesICC Moot Court Competition (International Rounds: Finalists) : Prosecution MemorialAmol Mehta89% (9)

- Petition For Bail AcramanDocument13 pagesPetition For Bail AcramanPrince JamilNo ratings yet

- NCNDADocument6 pagesNCNDApashazahariNo ratings yet

- Records Classification: Concepts, Principles and Methods: Information, Systems, ContextFrom EverandRecords Classification: Concepts, Principles and Methods: Information, Systems, ContextRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- CD - Gapayao v. Fulo, SSSDocument2 pagesCD - Gapayao v. Fulo, SSSJane SudarioNo ratings yet

- Civpro Answers (Midterm)Document5 pagesCivpro Answers (Midterm)Angel BangasanNo ratings yet

- Bar Exam GuideDocument14 pagesBar Exam GuideBarExamGuide0% (1)

- 2020 ISM CodeDocument11 pages2020 ISM CodeAndriyNo ratings yet

- Neil Maccormick: Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 10, No. 1. (Summer, 1983), Pp. 1-18Document21 pagesNeil Maccormick: Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 10, No. 1. (Summer, 1983), Pp. 1-18juansespinosaNo ratings yet

- Legal Research in The Computer Age DigestDocument3 pagesLegal Research in The Computer Age DigestPaoNo ratings yet

- DEED OF ADJUDICATION WITH ABSOLUTE SALE - VigillaDocument3 pagesDEED OF ADJUDICATION WITH ABSOLUTE SALE - VigillaAlfred AglipayNo ratings yet

- Systems Programming: Designing and Developing Distributed ApplicationsFrom EverandSystems Programming: Designing and Developing Distributed ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Ellis Model Information Seeking BehaviourDocument22 pagesEllis Model Information Seeking BehaviourRiki Cesc AriantoNo ratings yet

- NoortwijkDocument15 pagesNoortwijkCristina Sheen Estacio CameroNo ratings yet

- TSP Csse 47702Document18 pagesTSP Csse 47702Azka FatimaNo ratings yet

- 8171 Et Et PDFDocument11 pages8171 Et Et PDFshiva karnatiNo ratings yet

- Information SurveyDocument35 pagesInformation SurveySifonabasi IbongNo ratings yet

- Saravanan ThesisDocument207 pagesSaravanan ThesisUnimarks Legal Solutions100% (1)

- A Semi-Supervised Training Method For Semantic Search of Legal Facts in Canadian Immigration CasesDocument11 pagesA Semi-Supervised Training Method For Semantic Search of Legal Facts in Canadian Immigration CasesShuklaNo ratings yet

- Computer Assisted Legal Research With Special Reference To Indian Legal Contents: Retrospect and ProspectDocument17 pagesComputer Assisted Legal Research With Special Reference To Indian Legal Contents: Retrospect and ProspectRaynold DharNo ratings yet

- Article SampleDocument9 pagesArticle Sampleradharani sharmaNo ratings yet

- Information Retrieval Is A Complex Process Because There Is No Infallible Way To Provide A Direct Connection Between A UserDocument4 pagesInformation Retrieval Is A Complex Process Because There Is No Infallible Way To Provide A Direct Connection Between A UserOscar GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Importance and Objectives Legal ResearchDocument6 pagesThe Importance and Objectives Legal Researcharjav jainNo ratings yet

- (PDF) Legal Research Methodology: An OverviewDocument24 pages(PDF) Legal Research Methodology: An OverviewMadhav ZoadNo ratings yet

- 1904 01719 PDFDocument10 pages1904 01719 PDFr90cj7cm9xj1sNo ratings yet

- Journal 5 PDocument44 pagesJournal 5 PsastaplanNo ratings yet

- Komputerisasi Penelitian Hukum DGN Teknologi Data MiningDocument8 pagesKomputerisasi Penelitian Hukum DGN Teknologi Data MiningsunnysamsuniNo ratings yet

- Audit AssignmentDocument1 pageAudit AssignmentsixstriderNo ratings yet

- Blair and Maron - 1985 - An Evaluation of Retrieval Effectiveness For A Full-Text Document-Retrieval SystemDocument11 pagesBlair and Maron - 1985 - An Evaluation of Retrieval Effectiveness For A Full-Text Document-Retrieval SystemChuck RothmanNo ratings yet

- The Centrality of User Modeling To High Recall With High Precision SearchDocument6 pagesThe Centrality of User Modeling To High Recall With High Precision SearchBhuvana SakthiNo ratings yet

- Legal Document Retrieval Using Document Vector Embeddings and Deep LearningDocument9 pagesLegal Document Retrieval Using Document Vector Embeddings and Deep LearningArunima MaitraNo ratings yet

- Singhal and MalikDocument5 pagesSinghal and MalikAlan WhaleyNo ratings yet

- LIBR256-11 - EAD & Online Access Tools FINISHED - Final - Black - PRNT - 5!1!09Document122 pagesLIBR256-11 - EAD & Online Access Tools FINISHED - Final - Black - PRNT - 5!1!09timtrevathansjsumlosNo ratings yet

- Big Data Mining Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesBig Data Mining Literature Reviewea884b2k100% (1)

- IJCER (WWW - Ijceronline.com) International Journal of Computational Engineering ResearchDocument4 pagesIJCER (WWW - Ijceronline.com) International Journal of Computational Engineering ResearchInternational Journal of computational Engineering research (IJCER)No ratings yet

- Criminal Case Search Using Binary Search AlgorithmDocument23 pagesCriminal Case Search Using Binary Search AlgorithmOkunade OluwafemiNo ratings yet

- Seminar Computerized Legal ResearchDocument4 pagesSeminar Computerized Legal ResearchTrupti DabkeNo ratings yet

- Journal 5 PDocument44 pagesJournal 5 PDiv' TripathiNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Mismatch Avoidance Techniques: AbstractDocument10 pagesVocabulary Mismatch Avoidance Techniques: AbstractsivakumarNo ratings yet

- Reviews of Related Literature and StudiesDocument12 pagesReviews of Related Literature and StudiesBinibini ShaneNo ratings yet

- What Are The Purpose and The Process of The Literature Review in Criminal Justice ResearchDocument6 pagesWhat Are The Purpose and The Process of The Literature Review in Criminal Justice ResearchafdtzvbexNo ratings yet

- QUESEM: Towards Building A Meta Search Service Utilizing Query SemanticsDocument10 pagesQUESEM: Towards Building A Meta Search Service Utilizing Query SemanticsKriti KohliNo ratings yet

- Measuring Query Complexity in Web-Scale Discovery A Comparison Between Two Academic LibrariesDocument12 pagesMeasuring Query Complexity in Web-Scale Discovery A Comparison Between Two Academic LibrariesJaime JaimexNo ratings yet

- Legal OntologiesDocument19 pagesLegal OntologiesXuan Truong DinhNo ratings yet

- Bhat COMPARATIVEMETHODLEGAL 2015Document28 pagesBhat COMPARATIVEMETHODLEGAL 2015VidoushiNo ratings yet

- Legal Text MiningDocument7 pagesLegal Text MiningIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Components Analysis Examination For Identifying Stronger Variables Related To Users' Satisfaction in Research Data Management Systems of Subject-Related Libraries in Colombo District, Sri LankaDocument15 pagesComponents Analysis Examination For Identifying Stronger Variables Related To Users' Satisfaction in Research Data Management Systems of Subject-Related Libraries in Colombo District, Sri LankaCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- Search Model For Searching The Evidence in Digital Forensic AnalysisDocument6 pagesSearch Model For Searching The Evidence in Digital Forensic AnalysisNewdelhiNo ratings yet

- RM ProjectDocument17 pagesRM ProjectDinkar JainNo ratings yet

- Research Monoghaph Mid AssignmentDocument13 pagesResearch Monoghaph Mid Assignmentnabildigital.comNo ratings yet

- A Study of Information Seeking and Retrieving. I. Background and MethodologyDocument16 pagesA Study of Information Seeking and Retrieving. I. Background and MethodologyswainanjanNo ratings yet

- Strathprints 002676Document27 pagesStrathprints 002676Nairoz GamalNo ratings yet

- Information Retrieval Algorithms: A Survey: Prabhakar RaghavanDocument8 pagesInformation Retrieval Algorithms: A Survey: Prabhakar RaghavanshanthinisampathNo ratings yet

- On The Role of File System Metadata in Digital ForensicsDocument15 pagesOn The Role of File System Metadata in Digital Forensicspj2513No ratings yet

- Selecting A Knowledge Management Collection StrategyDocument4 pagesSelecting A Knowledge Management Collection StrategyRon FriedmannNo ratings yet

- An Operational Test of KnowledgenetDocument5 pagesAn Operational Test of KnowledgenetBetsey MerkelNo ratings yet

- Doctrinal Legal Research Method A Guiding Principle in Reforming The Law and Legal System Towards The Research DevelopmentDocument3 pagesDoctrinal Legal Research Method A Guiding Principle in Reforming The Law and Legal System Towards The Research DevelopmentRogelio BataclanNo ratings yet

- Folksonomies Versus Automatic Keyword ExtractionDocument12 pagesFolksonomies Versus Automatic Keyword ExtractiontfnkNo ratings yet

- Entity Identification For Heterogeneous Database Integration A Multiple Classifier System Approach and Empirical EvaluationDocument14 pagesEntity Identification For Heterogeneous Database Integration A Multiple Classifier System Approach and Empirical EvaluationBruno VieiraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Survey SummaryDocument6 pagesThesis Survey SummaryminmenmNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document15 pagesModule 4MALLUPEDDI SAI LOHITH MALLUPEDDI SAI LOHITHNo ratings yet

- JurisprudenceDocument10 pagesJurisprudenceLmaoNo ratings yet

- Tools and Techniques of Data Collection in Legal ResearchDocument9 pagesTools and Techniques of Data Collection in Legal ResearchKashish ChhabraNo ratings yet

- Case Study Research in Software Engineering: Guidelines and ExamplesFrom EverandCase Study Research in Software Engineering: Guidelines and ExamplesNo ratings yet

- NHAI Updated ResearchDocument1 pageNHAI Updated Researchkumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Hydrographic Surveying in Exclusive Economic Zones: Jurisdictional IssuesDocument10 pagesHydrographic Surveying in Exclusive Economic Zones: Jurisdictional Issueskumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Kluwer International Tax Blog: "Global Minimum Tax: A Game Changer?"Document11 pagesKluwer International Tax Blog: "Global Minimum Tax: A Game Changer?"kumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1546242Document42 pagesSSRN Id1546242kumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Tax Sace 1Document13 pagesTax Sace 1kumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- SemIII-C 87 CG-I Kumarkartikeya ProjectDocument18 pagesSemIII-C 87 CG-I Kumarkartikeya Projectkumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Company Law 1Document3 pagesCompany Law 1kumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Tax Computation FY 2020-21Document9 pagesTax Computation FY 2020-21kumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Election Method of The PresidentDocument5 pagesElection Method of The Presidentkumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Modes of Acquisition Under International LawDocument12 pagesModes of Acquisition Under International Lawkumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Index: SEMESTER VI - B.A.LL.B. (Hons.) Syllabus (Session: Jan-June)Document48 pagesIndex: SEMESTER VI - B.A.LL.B. (Hons.) Syllabus (Session: Jan-June)kumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- The Indian Legal SystemDocument5 pagesThe Indian Legal Systemkumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- LLP Agreement - Shreya SinghDocument20 pagesLLP Agreement - Shreya Singhkumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Richard F. Caverly, at No. 17002, and James S. Rizek, at No. 17001 (Two Cases), 408 F.2d 1313, 3rd Cir. (1969)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Richard F. Caverly, at No. 17002, and James S. Rizek, at No. 17001 (Two Cases), 408 F.2d 1313, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument110 pages08 - Chapter 2 PDFIshaan HarshNo ratings yet

- What Are Checks and Balances? - The Constitution Unit - UCL - University CollegeDocument3 pagesWhat Are Checks and Balances? - The Constitution Unit - UCL - University CollegeJD PCUNo ratings yet

- Exemptions: Top 10 Points To Remember About From The California Public Records ActDocument3 pagesExemptions: Top 10 Points To Remember About From The California Public Records ActSamantha SmithNo ratings yet

- Test 1 PreguntasDocument45 pagesTest 1 PreguntasSebastian BarriaNo ratings yet

- N Limitation Act 1963 2417 Cnluacin 20210903 032644 1 42Document42 pagesN Limitation Act 1963 2417 Cnluacin 20210903 032644 1 42HJ ManviNo ratings yet

- Legcounsel © Michelle Duguil 1Document4 pagesLegcounsel © Michelle Duguil 1michelledugsNo ratings yet

- 4.cruz v. Gruspe - DigestDocument2 pages4.cruz v. Gruspe - DigestMarichu Castillo HernandezNo ratings yet

- The Maharashtra Shops and Establishments (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Rules, 2018Document2 pagesThe Maharashtra Shops and Establishments (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Rules, 2018Gopinath hNo ratings yet

- Hersel A. Willey v. Ira M. Coiner, Warden of The West Virginia State Penitentiary, 464 F.2d 525, 4th Cir. (1972)Document3 pagesHersel A. Willey v. Ira M. Coiner, Warden of The West Virginia State Penitentiary, 464 F.2d 525, 4th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Role of Banking in India Economic For Devlopment With Reference To Icici BankDocument116 pagesRole of Banking in India Economic For Devlopment With Reference To Icici BankMayankJainNo ratings yet

- Hall vs. PiccioDocument1 pageHall vs. Picciochester paul gawaranNo ratings yet

- Police RRDocument17 pagesPolice RRindrajitdhadhal400No ratings yet

- Future Link Systems v. AppleDocument14 pagesFuture Link Systems v. AppleMikey CampbellNo ratings yet

- Doctrine: The Lawyer's Oath Is NOT A Mere Ceremony or Formality For Practicing Law. Every Lawyer ShouldDocument1 pageDoctrine: The Lawyer's Oath Is NOT A Mere Ceremony or Formality For Practicing Law. Every Lawyer ShoulddadcansancioNo ratings yet

- Political Reform in BelizeDocument2 pagesPolitical Reform in BelizePup BelizeNo ratings yet

- Mens ReaDocument17 pagesMens ReaMenshova BogdanaNo ratings yet

- Consti2Digest - Tiu Vs CA 37 SCRA 99, GR 127410 (20 Jan. 1999)Document2 pagesConsti2Digest - Tiu Vs CA 37 SCRA 99, GR 127410 (20 Jan. 1999)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- 2014-05-15 Urging Rabbi Laura Owens To Dissociate Herself From Bet Tzedek - A Los Angeles Jewish Racket Headed by Sandor SamuelsDocument6 pages2014-05-15 Urging Rabbi Laura Owens To Dissociate Herself From Bet Tzedek - A Los Angeles Jewish Racket Headed by Sandor SamuelsHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet