Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EC Chicken

Uploaded by

Thư Huỳnh Trầm MinhCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EC Chicken

Uploaded by

Thư Huỳnh Trầm MinhCopyright:

Available Formats

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

ITL Compendium

International Trade Law (O.P. Jindal University)

StuDocu is not sponsored or endorsed by any college or university

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Contents

I. Tariffs and Quantitative Restrictions:............................................................................................2

Tariffs:..............................................................................................................................................2

Quantitative Restrictions:...............................................................................................................4

II.SPS and TBT....................................................................................................................................5

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (“SPS”) - Specific Agreement.........................................5

Technical Barriers to Trade............................................................................................................7

III.WTO Dispute Resolution System..................................................................................................9

IV. Trade Remedies............................................................................................................................13

Anti-Dumping................................................................................................................................13

Subsidies:........................................................................................................................................14

A. Non-Discrimination under WTO law:......................................................................................16

I. Most Favoured Nation...............................................................................................................16

II. National Treatment..................................................................................................................19

B. EXCEPTIONS...........................................................................................................................26

I. General Exceptions................................................................................................................26

II. Security exceptions under the GATT 1994 and the GATS..................................................33

III. Economic Exceptions.........................................................................................................33

IV. Regional Trade Exceptions................................................................................................33

V. Special and Different Treatment...........................................................................................34

C. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................36

D.HISTORY AND WTO AGREEMENT:........................................................................................36

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

I. Tariffs and Quantitative Restrictions:

Two conventional ways in governments have sought to control the import of commodities into their

territories, and sometimes, the export of commodities, are (a) tariffs, meaning that a ‘duty’ must be

paid to import/export a commodity, and (b) quantitative restrictions, determining the amount of a

commodity that can imported/exported, if at all. The WTO bans, in principle, all quantitative

restrictions, but allows for the imposition of tariffs. It then attempts to reduce the barrier posed by

tariffs in “tariff negotiations” among member countries.

Kinds of barriers- tariff barriers and non-tariff barriers

Tariff Barriers: Duty paid at entry at border (non-traders) (Also called border measures) custom

dutiesother duties and charges.

Non-Tariff Barriers: Border measures and non-border measures, quantitative restrictions (restriction

on quantity), anti-dumping duties, counter-veiling duties, residual category

Tariffs:

Custom duties allowed by WTO. Tax to be paid on imports or sometimes on exports.

Types of duties:

1. Specific: imposed on the quantity of the good. eg. per unit. You don’t have to calculate the

value of the good.

2. Ad Valorem: imposed on the value of the good. Most popular because works according to

market forces. No need to continuously revise.

3. Mixed: mixture of both.

Why do we impose tariffs?- protectionism, revenue (easy to collect tax as opposed to other taxes),

Sensitive Sector- no comparative advantage. No benefit by free trade. To remedy trade distortions

(anti-dumping).

Three components of Tariffs- (1) Rate (Schedule of concessions under Article 2) (2) Classification

(most countries now following the Harmonized system, document prepared by World Customs

Organization) and (3) the valuation of goods for tariff purposes.

Legal Framework

GATT Article 2 obligates Member countries to apply tariff rates that are no higher than their bound

rates (highest allowable tariff rate). Article II (1) (b) Any “other duties or charges” that belong to other

residual category- financial charges e.g. processing fee are to be mentioned in the schedule.

Article 2 (2) (a)- Members can impose a charge equivalent to internal tax not mentioned in the

schedule but this charge has to comply with provisions of paragraph 2 of Article III in respect of the

like domestic product. Article II(2)(b)- can apply anti-dumping or countervailing duty. Article II (2)

(c)-Fees or other charges commensurate with the cost of services rendered can be imposed. This has

to read with Article 8 (para 1)- which states that these charges must be the approximate cost of

services rendered and shall not represent an indirect protection to domestic products or a taxation of

imports or exports for fiscal purposes. Further Article 8 para 4 lays down fees, charges, formalities

and requirements imposed by governmental authorities in connection with importation and

exportation

GATT Article 28 specifies that when Members wish to raise their bound rates or withdraw tariff

concessions, they must negotiate and reach agreements with other Members with whom they had

initially negotiated and enter into consultations with major supplying countries that have a substantial

interest in any change in the bound rate. Article 28 (bis)- reduce custom duty.

Case Law Tariff:

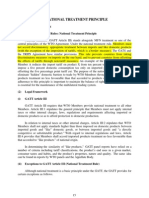

1. EC–Chicken Cuts case

Facts: In this case, the European Communities (the ‘EC’) departed from an established practice of

classifying imported chicken cuts that had been treated with salt under a lower-tariff heading (02.10,

covering ‘meat _ salted _’) and began to classify the increasing volume of such imports under a

higher-tariff heading (02.07, covering ‘ fresh, chilled or frozen’ poultry). EC argued that the

interpretation of “salted” category is for preservation but this chicken is not salted for preservation.

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Hence the general category of meat cuts. The complainants claimed violation of Article 2(1)(a) and

2(1)(b) against EC for applying duties and charges higher than the bound rates in schedule.

Issue: The parties, the Panel and the Appellate Body (AB) all dealt with this issue as a question of

treaty interpretation: the central task was to decide the meaning of “salted” in accordance with the

canons of treaty interpretation to be found in Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law

of Treaties (VCLT).

Analysis: The Panel and AB interpreted the norms in the Art. 31 and 32 VCLT as intended to be

applied sequentially: thus, it began with “ordinary meaning” in Art. 31(1), and having found that the

ordinary meaning of “salted” did not exclusively refer to salting for long term preservation then

proceeded to examine whether, in light of the other interpretative considerations in Art. 31 VCLT

(object, purpose and context), this was the proper meaning to attribute to tariff item 02.10. The AB

noted that it is appropriate to apply the VCLT in a holistic manner and that the factual considerations

in question could be taken into account either in considering “ordinary meaning” or in considering

“context”.

The AB reversed the Panel’s finding under VCLT Article 31(3)(b). It cannot be said that that the

consistent practice of the EC in classifying the products in question under 2.10 prior to 2002

constituted relevant “subsequent practice” establishing the common intent of the parties because

silence concerning one Member’s tariff classification practice does not constitutes assent to that

practice when other treaty parties that themselves have not engaged in a particular practice.

Since Schedules are annexed to GATT, they also looked at other schedules of other countries to

determine if salted means preservation. Dictionary meaning indicative but not determinative.

Although the Panel solicited advice from the WCO on the interpretation of 02.07 and 02.10, neither

the Panel nor the AB suggested that the WTO dispute settlement organs must, as a matter of law, defer

to WCO interpretations or practice with respect to HS classifications.

2. EC – LAN

Facts: In EC – Computer Equipment (1998), at issue was a dispute between the United States and the

European Communities on whether the EC’s tariff concessions regarding automatic data-processing

equipment applied to local area network (LAN) computer equipment.

Holding: The panel based its interpretation of the EC’s tariff concessions on the ‘legitimate

expectations’ of the exporting Member, in casu, the United States. On appeal, the AB rejected this

approach to the interpretation of tariff concessions, ruling as follows:

The purpose of treaty interpretation under Article 31 of the Vienna Convention is to ascertain

the common intentions of the parties. These common intentions cannot be ascertained on the basis of

the subjective and unilaterally determined ‘expectations’ of one of the parties to a treaty. Tariff

concessions provided for in a Member's Schedule – the interpretation of which is at issue here – are

reciprocal and result from a mutually advantageous negotiation between importing and exporting

Members. A Schedule is made an integral part of the GATT 1994 by Article II:7 of the GATT 1994.

Therefore, the concessions provided for in that Schedule are part of the terms of the treaty. As such,

the only rules which may be applied in interpreting the meaning of a concession are the general rules

of treaty interpretation set out in the Vienna Convention.

For the reasons stated above, we conclude that the Panel erred in finding that ‘the United States was

not required to clarify the scope of the European Communities’ tariff concessions on LAN

equipment’. We consider that any clarification of the scope of tariff concessions that may be required

during the negotiations is a task for all interested parties.

India – Additional Import Duties Cases

Facts: India imposed additional import duties on alcohol and called it internal tax (exception under

Article 2, para 2).

Holding: Appellate Body held that the custom duties are legitimate means to protect domestic

producers recognized by WTO as opposed to panel finding that the custom duties are inherently

discriminatory (WTO foundation erase all barriers). The internal taxes should be equal in amount and

nature. Just because they are equal in function does not help. India violated the WTO obligations.

Further India argued that it can refund the excess amount, but Appellate body did not find any refund

mechanism. Trend- India losing cases because of lack of evidence.

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Argentina – Textiles and Apparel (1998)- the application of a type of duty different from the type

provided for in a Member's Schedule is only inconsistent with Article II:1(b) to the extent that it

results in customs duties being imposed in excess of those set forth in that Member's Schedule.

Quantitative Restrictions:

There are different types of quantitative restriction: (1) a prohibition, on the importation or

exportation of a product; such a prohibition may be absolute or conditional, i.e. only applicable when

certain defined conditions are not fulfilled; (2) an import or export quota, (3) import or

export licensing, (4) other quantitative restrictions, such as a quantitative restriction made effective

through State trading operations; a mixing regulation; a minimum price, triggering a quantitative

restriction; and a voluntary export restraint.

Reasons for prohibition of Quantitative Restrictions:

(1) One reason for this prohibition is that quantitative restrictions are considered to have a greater

protective effect than do tariff measures and are more likely to distort the free flow of trade. When a

trading partner uses tariffs to restrict imports, it is still possible to increase exports as long as foreign

products become price-competitive enough to overcome the barriers created by the tariff. When a

trading partner uses quantitative restrictions, however, it is impossible to export in excess of the quota

no matter how price competitive foreign products may be. Thus, quantitative restrictions are

considered to have such a distortional effect on trade that their prohibition is one of the fundamental

principles of the GATT. (2) In addition, import quotas may not always be administered fairly. Tariffs

are more transparent.(3) Tariff better for the state as they generate revenue. (4) Tariff easier to

negotiate.

Legal Framework:

Article 11 of the GATT generally prohibits quantitative restrictions on the importation or the

exportation of any product by stating that “No prohibitions or restrictions other than duties, taxes or

other charges shall be instituted or maintained by any Member . . ..”

Exceptions to Article 11

Exceptions Provided in GATT Article 11: (1) Export prohibitions or restrictions temporarily applied

to prevent or relieve critical shortages of foodstuffs essential to the exporting WTO Member

(Paragraph 2 (a)); (2) Import and export prohibitions or restrictions necessary to the application of

standards or regulations for the classification, grading or marketing of commodities in international

trade (Paragraph 2 (b)); and (3) Import restrictions on any agricultural or fisheries product, necessary

to the enforcement of governmental measures which operate to restrict production of the domestic

product or for certain other purposes (Paragraph 2 (c)).

Other Articles: (1) General exceptions for measures such as those necessary to protect public morals

or protect human, animal, or plant life or health (Article XX); (2) Exceptions for security reasons

(Article XXI). (3) Restrictions to safeguard the balance of payments 1(Article XII regarding all WTO

Members; Article XVIII:B regarding developing WTO Members in the early stages of economic

development); (4) Quantitative restrictions necessary to the development of a particular industry by a

WTO Member in the early stages of economic development or in certain other situations (Article

XVIII:C, D).

Article 13

What Article XIII:1 requires is that, if a Member imposes a quantitative restriction on products to or

from another Member, products to or from all other countries are ‘similarly prohibited or restricted’.

This requirement of Article XIII:1 is an MFN-like obligation. As the Appellate Body noted in EC –

Bananas III (1997), the essence of the non-discrimination obligations of Articles I:1 and XIII of the

GATT 1994 is that:like products should be treated equally, irrespective of their origin.

1 The balance of payments is the record of all international financial transactions made by a country's residents.

A country's balance of payments tells you whether it saves enough to pay for its imports. A balance of

payments deficit means the country imports more goods, services and capital than it exports. It must borrow

from other countries to pay for its imports.

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Case Law:

Argentina – Hides and Leather (2001)

Issue: The issue arose whether Argentina violated Article XI:1 by authorising the presence of

domestic tanners’ representatives in the customs inspection procedures for hides destined for export

operations. According to the European Communities, the complainant in this case, Argentina, imposed

a de facto restriction on the exportation of hides inconsistent with Article XI:1. The panel ruled:

Analysis: However, the panel concluded with respect to the Argentinian regulation providing for the

presence of the domestic tanners’ representatives in the customs inspection procedures that there was

insufficient evidence that this regulation actually operated as an export restriction inconsistent with

Article XI:1 of the GATT 1994. According to the panel, there was ‘no persuasive explanation of

precisely how the measure at issue causes or contributes to the low level of exports.

Colombia – Ports of Entry (2009)

Taking a different from Argentina case, the panel in Colombia – Ports of Entry (2009) stated,

however, that: to the extent Panama were able to demonstrate a violation of Article XI:1 based on the

measure's design, structure, and architecture, the Panel is of the view that it would not be necessary to

consider trade volumes or a causal link between the measure and its effects on trade volumes.

EEC – Apples (Chile I) (1980)- The panel in EEC – Apples (Chile I) (1980) found that the measure

applied to apple imports from Chile were not a restriction similar to the voluntary restraint

agreements negotiated with the other apple-exporting countries and therefore was inconsistent with

Article XIII:1. The import restriction was unilateral and mandatory in case of Chile while the for

other countries it was voluntary and negotiated.

II.SPS and TBT

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (“SPS”) - Specific Agreement

Why do these exist? The negotiators of the WTO agreements considered that these measures merited

special attention for two reasons: (1) because the preservation of domestic regulatory autonomy was,

and still is, considered of particular importance where health risks are at issue; and, (2) because of the

close link between SPS measures and agricultural trade, a sector that is notoriously difficult to

liberalise. However, in recent years SPS measures are increasingly used as instruments of ‘trade

protectionism’ (think of an exacting standard that only a domestic producer can meet).

SPS and TBT: specific over general

SPS and GATT: SPS and GATT can hardly conflict

Legal Framework:

Preamble: Chapeau of Article 20 of GATT, multilateralism instead of bilateralism- as the former

ensures more equality, harmonizing international standards, members may choose any level of

protection-subject to Article 5 requirement of risk assessment.

Article 1.1- for a measure to be subject to the SPS Agreement, it must be: (1) a sanitary or

phytosanitary measure; and (2) a measure that may affect international trade. SPS measure’, is defined

in paragraph 1 of Annex A. The aim of the measure must be looked at- protect human, animal, plant

life or health, scope of the measure, no extra-territorial application.

In broad terms, an ‘SPS measure’ is one that: (1) aims at the protection of human or animal life or

health from food-borne risks; or (2) aims at the protection of human, animal or plant life or health

from risks from pests or diseases; or (3) aims at the prevention or limitation of other damage from

risks from pests.

Article 2- This section discusses the following basic principles of the SPS Agreement: (1) the

sovereign right of WTO Members to take SPS measures; (2) the obligation to take or maintain only

SPS measures necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health (the ‘necessity

requirement’); (3) the obligation to take or maintain only SPS measures based on scientific principles

and on sufficient scientific evidence (the ‘scientific disciplines’). The EC Hormones case held that

while determining sufficient evidence- bear in mind that responsible, representative governments

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

commonly act from perspectives of prudence and precaution where risks of irreversible, e.g. life-

terminating, damage to human health are concerned; and (4) the obligation not to adopt or maintain

SPS measures that arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate or constitute a disguised restriction on trade

(the ‘non-discrimination’ requirement).

Article 3- Members may choose to: (1) base their SPS measures on international standards according

to Article 3.1; (2) conform their SPS measures to international standards under Article 3.2; or (3)

impose SPS measures resulting in a higher level of protection than would be achieved by the relevant

international standard in terms of Article 3.3. EC Hormones- Base is looser standard than ‘conform

to’.

For Article 3.3: This right to choose measures that deviate from international standards is not an

‘absolute or unqualified right’, as confirmed by the AB in EC – Hormones (1998). Two

alternative conditions are laid down in Article 3.3, namely, that: (1) either there must be a scientific

justification for the SPS measure (defined in a footnote as a scientific examination and evaluation in

accordance with the rules of the SPS Agreement); or (2) the measure must be a result of the level of

protection chosen by the Member in accordance with Articles 5.1 to 5.8. The difference between these

two conditions is not clear and the Appellate Body noted, in EC – Hormones (1998) what is clear,

however, is that under both alternative conditions a risk assessment in terms of Article 5.1 is required.

Therefore, the Appellate Body held in EC – Hormones (1998) that, given that the European

Communities had established for itself a level of protection higher than that implied in the relevant

Codex standards, it was bound to comply with the requirements established in Article 5.1

Article 5

Article 5.1.- whether the SPS measure at issue is ‘based on’ this risk assessment. The meaning of

‘based on’ was clarified in EC – Hormones (1998). It held that, for an SPS measure to be ‘based on’ a

risk assessment, there must be a ‘rational relationship’ between the measure and the risk assessment,

and the risk assessment must ‘reasonably support’ the measure. Paragraph 4 of Annex A defines risk

assessment- 2 types: (1) aimed at risks from pests or diseases and (2) aimed at food-borne risks.

Article 5.2, however, lists, in a non-exhaustive manner, certain factors to be taken into account like

scientific data. Article 5.3 identifies the economic factors that Members shall take into account.

Article 5.4.- good faith obligation to minimize negative trade effects of SPS measure. Article 5.5- To

establish whether an SPS measure is inconsistent with Article 5.5, three questions need to be

answered: (1) whether there are different levels of protection in different situations; (2) whether these

different levels of protection show arbitrary or unjustifiable differences in their treatment of different

situations; and (3) whether these arbitrary or unjustifiable differences lead to discrimination or

disguised restrictions on trade [EC Hormones]. Article 5.6 (read with 2.2)- an SPS measure may be

found to be WTO-inconsistent if an alternative, significantly less trade-restrictive measure which

would achieve the Member's ALOP is reasonably available, taking into account technical and

economic feasibility. Article 5.7- Precautionary Principle- in cases where relevant scientific evidence

is insufficient, a Member may provisionally adopt sanitary or phytosanitary measures on the basis of

available pertinent information, including that from the relevant international organizations as well as

from sanitary or phytosanitary measures applied by other Members. EC Hormones: precautionary

principle specific to Article 5.7 situation- cannot be used for pan SPS agreement to add flexibility to

scientific disciplines of Article 5.1 and Article 2.2.

Article 6- para 1- take into account the territorial context of the measure.

Article 7- Members to notify changes in their SPS measures and to provide information on their SPS

measures according to Annex B to the SPS Agreement.

Article 9, para 2:technical assistance to adjust or comply with SPS measures.

Article 10- special and differential treatment for developing countries. Para 1 ‘shall take into account’

difficulties in implementation (time relaxations) and in complying with SPS measures. EC –

Approval and Marketing of Biotech Products- Argentina argued that 10.1 was of mandatory nature

and due to special needs of developing country, EC should provide ‘preferential market access’ for

developing-country products. The Panel held that the obligation to ‘take account’ of developing-

country needs merely requires Members ‘to consider’ the needs of developing countries. This

obligation, according to the panel, does not prescribe a particular result to be achieved, and notably

does not provide that the importing Member must invariably accord special and differential treatment.

Article 11- Dispute Settlement- para 3- alternate methods .

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Article 12- para 1 and 2 read with Annex A para 2 (definition of harmonization).

EC Hormones: Facts: Synthetic hormones can be naturally occurring or in may be injected in bovine

meat- EC banned products with these hormones- unless they are naturally occurring or if backed by a

specific reason. Holding: The Appellate Body submitted its report, finding that the EU measures were

not to be regarded as discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade and therefore not

inconsistent with Article 5.5 of the SPS Agreement. On the other hand, it upheld the panel's findings

that the EU measures were not based on sufficient assessment of risk, and therefore found it to be in

violation of Article 5.1 of the SPS Agreement. AB found the burden of proof to meet requirements to

be incumbent on the complaining country (in this case, the United States).

Technical Barriers to Trade

Has three components: a) Technical Regulations: A legal instrument that lays down certain

characteristics for an identifiable product for which compliance is mandatory, b) Standard: A legal

instruments that lays down certain characteristics for an identifiable product for which compliance is

not mandatory, c) conformity assessment procedure-any procedure used to determine that relevant

requirements in technical regulations or standards are fulfilled. See Annex 1.

Agreement applies to member central government must ensure that regional governments and

provisional local governments must adhere to the agreement

Relationship between TBT agreement and SPS agreement: TBT is general and SPS is specific and

therefore application of SPS. EC-Hormones: panel found, that, since the measures were SPS

measures, the TBT Agreement did not apply.

Relationship between TBT and GATT: TBT will prevail over GATT because specific prevails over

TBT. The panel in EC – Asbestos (2001) held that, in a case where both the GATT 1994 and the TBT

Agreement appear to apply to a given measure, a panel must first examine whether the measure at

issue is consistent with the TBT Agreement since this agreement deals ‘specifically and in detail’ with

technical barriers to trade.

TBT also has some additional provisions relating to the spirit of TBT- recognition of members’ right

to take measures regarding technical barriers and they can choose the level of such measures

Obstacles for exporters- additional cost for producers as different importers may have different

criteria- technical regulations should be harmonised so that exporters comply with fewer regulations-

hence these standards should be based on international standard.

Members right to choose level of protection will prevail over the obligation to base the technical

regulation on the international standard. Level of protection, technology and climatic impact- these

are used to justified lack of adherence to international standard in drafting domestic regulation.

Legal Framework

Preamble: recognizes that TB can be an obstacle to trade and therefore permits TBs only to extent

that it doesn’t cause unnecessary obstacles, TBT is an enabling provision not a mandatory obligation,

technical regulations can be for imports as well as exports, environment is explicitly mentioned unlike

in Article 20, “subject to the requirement that they are not applied in a manner which would

constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination” Chapeau of Article 20, “at the levels

it considers appropriate” members can choose the level

Difference between Article 20 GATT and TBT: TBT is more scientific, less ambiguous, cannot be

misused, TBT is used more by developed countries like EC, TBT has specific components as

discussed above.

Article 1.1 and 1.2: linkage of WTO law with non-WTO law- when TBT doesn’t define anything we

look at UN

Article 1.3 and 1.5: 1.3-product coverage and 1.5- TBT and SPS are mutually exclusive agreements.

Article 2: Technical Regulations and standards:

2.1: national treatment and MFN, 2.2: aim and effect test, article 20 jurisprudence- necessity of

regulation, non-exhaustive list of legitimate objectives, relevant elements of consideration for risks of

not fulfilling the legitimate objectives- scientific and technical information- this measure introduces

science to WTO. 2.3- Article 20 jurisprudence. Article 2.4: relevant technical regulations should be

used as a basis for technical regulation unless the technical regulation will not be appropriate or

effective in fulfilling the legitimate objective. The panel in EC – Sardines (2002) found that the

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

international standard ‘Codex Stan 94’, developed by an international food-standard-setting body, the

Codex Alimentarius Commission, and the EC’s technical regulation at issue both covered the same

product (Sardina pilchardus). They both also included similar types of requirements as regards this

product, such as those relating to labelling, presentation and packing medium. The panel, therefore,

concluded that the Codex Stan 94 was a relevant international standard for the EC’s technical

regulation at issue. Further, the relevant international standard need not adopted by consensus in the

relevant international standardising body. AB in EC – Sardines (2002) ruled that it is for the

complainant to demonstrate that the international standard in question is both an effective and an

appropriate means to fulfil the legitimate objective.

Article 2.9- procedure before adoption, 2.10- procedure after adoption in exceptional cases where 2.9

cannot be followed- very wide import- could be very restrictive of trade, 2.12- takes into account

developing countries- usually 6 months (US-cloves case).

Article 3.4 and 3.5- Central government obligations to ensure compliance with Article 2. Article 4.1-

Code of Good Practice- basic principles have been enshrined in Annex 3. Article 5.6- Transparency

requirements for conformity assessment procedure. Article 5.7- similar to 2.10 for conformity

assessment procedure. Article 5.8 and 5.9- similar to 2.11 and 2.12 for conformity assessment

procedure. Article 10: Specific provisions to help developing countries: Information About Technical

Regulations, Standards and Conformity Assessment Procedures: Making other members aware, if you

abstain that is in violation of TBT. Article 11-Technical Assistance to Other Members, Article 12:

Special and Differential Treatment of Developing Country Members. Article 13: The Committee on

Technical Barriers to Trade. Article 14 Consultation and Dispute Settlement: 14.2 – technical

assistance as specified in Article 13 of DSU.

Case Law:

EC – Asbestos 2001

Facts: The measure at issue consisted of, on the one hand, a general ban on asbestos and asbestos-

containing products and, on the other hand, some exceptions referring to situations in which asbestos-

containing products would be allowed.

Issue: whether the measure at issue was a ‘technical regulation?

Holding: The panel concluded that the ban itself was not a technical regulation, whereas the

exceptions to the ban were. On appeal, the Appellate Body first firmly rejected the panel's approach

of considering separately the ban and the exceptions to the ban. According to the Appellate Body, the

‘proper legal character’ of the measure cannot be determined unless the measure is looked at as a

whole, including both the prohibitive and the permissive elements that are part of it. The Appellate

Body then examined whether the measure at issue, considered as a whole, was a technical regulation

within the meaning of the TBT Agreement. On the basis of the definition of a ‘technical regulation’ of

Annex 1.1, quoted above, the Appellate Body set out a number of considerations for

determining whether a measure is a technical regulation.

First, for a measure to be a ‘technical regulation’, it must ‘lay down’ – i.e. set forth, stipulate or

provide – ‘product characteristics’ that include objectively definable ‘features’, ‘qualities’,

‘attributes’, or other ‘distinguishing mark’ of a product. The second sentence of Annex 1 also includes

related extrinsic ‘characteristics’, such as the means of identification, the presentation and the

appearance of a product. Second, ‘technical regulation’ has the effect of prescribing or imposing one

or more ‘characteristics’. The product characteristics may be prescribed or imposed in either

a positive or a negative form. Third, held that a ‘technical regulation’ must ‘be applicable to

an identifiable product, or group of products. No need to expressly identify products by name, but

simply makes them identifiable – for instance, through the ‘characteristic’ that is the subject of

regulation. Based on these 3 considerations, it held measure constituted a technical regulation.

EC-Sardines (2002)

Facts: The measure at issue in EC – Sardines (2002) was an EC regulation setting out a number of

prescriptions for the sale of ‘preserved sardines’, including a requirement that a product sold under the

name ‘preserved sardines’ contained only one species of sardines (namely, the Sardina pilchardus

Walbaum), to the exclusion of other species (such as the Sardinops sagax).

Issue: Whether the measure is a technical regulation?

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Holding: Confirmed the EC Asbestos ruling. established a three-tier test for determining whether a

measure is a ‘technical regulation’ under the TBT Agreement: • the measure must apply to

an identifiable product or group of products;• the measure must lay down product characteristics; and

•compliance with the product characteristics laid down in the measure must be mandatory.

Analysis: As the enforcement of the EC Regulation had led to a prohibition against

labelling Sardinops sagax as ‘preserved sardines’, this product was considered to be ‘identifiable’.

With regard to the second element of the three-tier test, the question arose as to whether a ‘naming’

rule, such as the rule that only Sardina pilchardus could be named ‘preserved sardines’, laid down

product characteristics. The Appellate Body held in this respect that product characteristics include

means of identification and that, therefore, the naming rule at issue definitely met the requirement of

the second element of the test. As the European Communities did not contest that compliance with the

Regulation at issue was mandatory, the Appellate Body found that the third element of the three-tier

test was also met, and the measure was therefore a ‘technical regulation’ for purposes of the TBT

Agreement.

With respect to the issue of application- Panel and AB held that it can be concluded that the TBT

Agreement applies to technical regulations, which, although adopted prior to 1995, are still in force.

US – Clove Cigarettes

Facts: In US – Clove Cigarettes (2012), concerned a US ban on clove cigarettes and other flavoured

cigarettes, with the exception of menthol cigarettes. Menthol is domestically produced but clove was

imported from Indonesia- Claim of violation of national treatment clause in TBT.

Issue: There was no contention between the parties whether it’s a technical regulation. Whether there

is a violation of MFN treatment obligation of Article 2.1.?

Holding: Appellate Body ruled that:[f]or a violation of the national treatment obligation in Article 2.1

to be established, three elements must be satisfied: (i) the measure at issue must be a technical

regulation; (ii) the imported and domestic products at issue must be like products; and (iii) the

treatment accorded to imported products must be less favourable than that accorded to like domestic

products. The Appellate Body in US – Clove Cigarettes (2012) unmistakably opted for a competition-

based approach to the determination of ‘likeness’ under Article 2.1. It stated that the determination of

‘likeness’ under Article 2.1 of the TBT Agreement is, as under Article III:4 of the GATT 1994: a

determination about the nature and extent of a competitive relationship between and among the

products at issue.

The United States did not appeal the panel's findings regarding ‘physical characteristics’ or ‘customs

classification’. It did appeal the panel's findings regarding ‘end-uses’ and ‘consumers’ tastes and

habits’. While the Appellate Body disagreed with certain aspects of the panel's analysis, it did agree

with the panel that the ‘likeness’ criteria it examined supported its overall conclusion that clove

cigarettes and menthol cigarettes are ‘like’ products within the meaning of Article 2.1 of the TBT

Agreement.

The Appellate Body noted, however, that regulatory concerns underlying a measure, such as the

health risks associated with a given product, may be relevant to an analysis of the ‘likeness’ criteria

under Article III:4 of the GATT 1994, as well as under Article 2.1 of the TBT Agreement, to the extent

they have an impact on the competitive relationship between and among the products concerned.

The Appellate Body interpreted the ‘treatment no less favourable’ requirement of Article 2.1 as:

prohibiting both de jure and de facto discrimination against imported products (Similar to

jurisprudence on Article III:4 GATT), while at the same time permitting detrimental impact on

competitive opportunities for imports that stems exclusively from legitimate regulatory distinctions

(no Article XX like GATT). The Appellate Body held that the design, architecture, revealing structure,

operation and application of the measure at issue (a US ban on clove cigarettes and other flavoured

cigarettes, with the exception of menthol cigarettes) strongly suggested that the detrimental impact on

competitive opportunities for clove cigarettes reflects discrimination against the group of like

products imported from Indonesia. Note that the ‘vast majority’ of clove cigarettes consumed in the

United States came from Indonesia, while almost all menthol cigarettes consumed in the United States

were produced in the United States. Moreover, the Appellate Body was not persuaded that the

detrimental impact of the measure at issue on competitive opportunities for imported clove cigarettes

stemmed from a legitimate regulatory distinction.

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

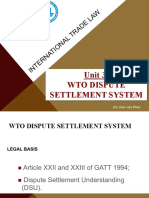

III.WTO Dispute Resolution System

A defining feature of the WTO legal system is its binding, and often effective, dispute resolution

system, which marks a clean break from the ‘weak’ enforcement regimes in international law

generally. This often makes WTO law, appear more ‘law’ like when compared to public international

generally. DSU negotiated during the Uruguay Round.

WTO compared with other International Dispute Resolution Bodies: (1) The WTO dispute

settlement system has been operational for eighteen years now. (2) Between 1 January 1995 and 31

December 2012, a total of 454 disputes have been brought to the WTO for resolution. In more than a

fifth of the disputes brought to the WTO, the parties were able to reach an amicable solution through

consultations, or the dispute was otherwise resolved without recourse to adjudication. In other

disputes, parties have resorted to adjudication. (3) During the same period, the International Court of

Justice (ICJ) in The Hague rendered fifty-four judgments and six advisory opinions, and the

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in Hamburg rendered sixteen judgments and

one advisory opinion. (4) Most importantly, however, in more than eight out of ten disputes in which

the respondent had to withdraw (or amend) a WTO-inconsistent measure, it did so in a timely manner.

(5) The WTO dispute settlement system has been used by developed-country Members and

developing-country Members alike. In 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2008, 2010 and 2012, developing-

country Members brought more disputes to the WTO for resolution than developed-country Members.

(6) Some disputes have triggered considerable controversy and public debate and have attracted much

media attention.

GATT to WTO: Shift from GATT to WTO. Creation of a formalist body. Juridification.

Under GATT no defined procedure- consent of the parties to start and execute the solution. More

diplomacy rather than a dispute settlement unit. (1)Internal nature of dispute: GATT closed knit

environment, nothing spills over another dimension. Homogenous membership. Most people from

trade ministries. Area of low politics, not much media attention. (2) Discreet nature of dispute: Choice

of panel acceptable to parties (3) diplomats and ex-diplomats belonging to the WTO network. Less

emphasis on expertise and knowledge. (4) Government is the state, no third-party participation or

third-party consequence-Tuna Dolphin case. (5) Confidentiality of dispute: Inherent to diplomacy.

Proceedings, only parties concerned participated, no third parties. Many cases never came out,

delayed reporting.

Legal culture of WTO: (1) legal dispute- winning or losing rather than settling-gets media attention.

(2) everyone is equal in court- power is shifted to the lawyers from might of the state on the

negotiating table under GATT. lawyers advise whether to sue or not. Empowerment of the role of

lawyer within the state and at WTO. (3) Reports of panel used to be worded in amicable manner, not

indicative of finality of adjudication but an appeal to parties. Now the rulings are opinionated, final

and strong. (4) private counsels could appear- third parties can appear, submit briefs..

Dissonance because of transition. Internal (how internal actors see it, GATT preferable by state

because of diplomacy) and External (how the institution is looked at from outside, eg. GATT looked

like a weak institution) legitimacy. There is a conflict between law and diplomacy. Confidentiality of

diplomacy v. objectivity and transparency of law. In the psychology of the people working at WTO it

is still of diplomacy even if the WTO has become a legalised body.

Negotiation or Adjudication- Thomas J. Dillon: Ultimately comes down to negotiation because of

inability to enforce. Increased efforts to judicialise the proceeding might backfire if the loosing parties

rebuff the WTO’s attempt to enforcement. Can lead to hostilities between the disputing parties

Negotiation could be undermined by adjudication when adjudication proves ineffective. Problematic

when the party in violation is one of the powerful economies and is unwilling to accept the decision.

Article 23 is very meticulously drafted to avoid any such disregard for WTO. It doesn’t provided for a

redress through the dispute mechanism but through cross-retaliation. Remains to be a negotiating

institution.

Legal Framework:

10

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

GATT

Article 22- Consultation for matters affecting the operation of the agreement.

Article 23(1)- If any Member should consider that any benefit accruing to it directly or indirectly

under this Agreement is being nullified or impaired or that the attainment of any objective of the

Agreement is being impeded as the result of (a) the failure of another Member to carry out its

obligations under this Agreement, or (b) the application by another Member of any measure, whether

or not it conflicts with the provisions of this Agreement, or (c)the existence of any other situation, the

Member may, with a view to the satisfactory adjustment of the matter, make written representations or

proposals to the other Member or Members which it considers to be concerned. According to the

panel in EC – Asbestos (2001), nullification or impairment would exist, in the case before it, if the

measure ha[s] the effect of upsetting the competitive relationship between Canadian asbestos and

products containing it, on the one hand, and substitute fibres and products containing them, on the

other. Further, the non-violation nullification or impairment] remedy … ‘should be approached with

caution and should remain an exceptional remedy’. Note: None of the non-violation

complaints brought to the WTO to date has been successful.

Article XXIII, GATS,

Article 64, TRIPS

DSU

Article 23.1- Exclusive jurisdiction of WTO dispute settlement under the covered agreements. Article

23.2(a)- Members may not make a unilateral determination that a violation of WTO law has occurred

and may not take retaliation measures unilaterally in the case of a violation of WTO law.

Arbitration related provisions: Pursuant to Article 25 of the DSU, parties to a dispute arising under

a covered agreement may decide to resort to arbitration as an alternative means of binding dispute

settlement, rather than have the dispute adjudicated by a panel and the Appellate Body. When parties

opt for arbitration, they must agree on the procedural rules that will apply to the arbitration process;

and they must explicitly agree to abide by the arbitration award. Arbitration awards need to be

consistent with WTO law, and must be notified to the DSB where any Member may raise any point

relating thereto. To date, Members have resorted only once to arbitration under Article 25 of the DSU.

The DSU also provides for arbitration in Articles 21.3(c) and Article 22.6. As discussed below, these

arbitration procedures concern specific issues that may arise in the context of a dispute, such as the

determination of the reasonable period of time for implementation (Article 21.3(c) of the DSU) and

the appropriate level of retaliation (Article 22.6 of the DSU). Members frequently resort to arbitration

under Article 21.3(c) or 22.6.

Article 3.2- clarify existing provisions-use customary rules of interpretation of public international

law. Japan Alcoholics Beverages II- Vienna convention- customary rule.

Article 5: the DSU also provides for good offices, conciliation and mediation as methods of dispute

settlement. They may begin at any time and be terminated at any time. Their use requires the

agreement of all parties to the dispute.

Article 24 – Special Procedures for Least Developed Countries:

Article 24 (1)- Members shall exercise due restraint in raising matters under these DSU procedures

involving a least-developed country Member. If nullification or impairment is found to result from a

measure taken by a least-developed country Member, complaining parties shall exercise due restraint

in asking for compensation or seeking authorization to suspend the application of concessions or other

obligations pursuant to these procedures. Mediation, conciliation and good offices available under

Article 24(2).

Flow Chart of process followed once DSB has adopted panel/AB report:

11

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Remedies: The DSU provides for three types of remedy for breach of WTO law: one final remedy,

namely, the withdrawal (or modification) of the WTO-inconsistent measure (Article 3.7); and two

temporary remedies which can be applied pending the withdrawal (or modification) of the WTO-

inconsistent measure, namely, compensation (Article 22) and suspension of concessions or other

obligations (commonly referred to as ‘retaliation’). The DSU Article 22.1 makes clear that

compensation and/or the suspension of concessions or other obligations are not alternative remedies,

which Members may want to apply instead of withdrawing (or modifying) the WTO-inconsistent

measure.

The retaliation remedy- Need authorisation from DSB. With regard to the concessions or other

obligations that may be suspended, Article 22.3 of the DSU provides that: (1) the complaining party

should first seek to suspend concessions or other obligations with respect to the same sector(s) as that

in which a violation was found; (2) if that is not practicable or effective, the complaining party may

seek to suspend concessions or other obligations in other sectors under the same agreement; and (3) if

also that is not practicable or effective, the complaining party may seek to suspend concessions or

other obligations under another covered agreement. Article 22.4- retaliation of the same level as the

amount of impairment/nullification, not punitive. Pursuant to Article 22.6 of the DSU, disputes

between the parties on the level of nullification or impairment, and thus on the appropriate level of

retaliation, are to be resolved through arbitration by the original panel.

Implementation of Ruling: Article 22.1- Prompt compliance with recommendations or rulings of the

DSB. However, if it is impracticable to comply immediately with the recommendations and rulings,

and this may often be the case, the Member concerned has, pursuant to Article 21.3 of the DSU, a

reasonable period of time in which to do so. The ‘reasonable period of time for implementation’ may

be: (1) agreed on by the parties to the dispute; or (2) determined through binding arbitration at the

request of either party. Article 21.3(c) of the DSU-the reasonable period of time to implement panel

or Appellate Body recommendations should not exceed 15 months from the date of adoption of a

panel or Appellate Body report. EC Hormones (1998)- the fifteen-month period mentioned in Article

21.3(c) of the DSU is a mere guideline for the arbitrator and that it is neither an ‘outer limit’ nor, of

course, a floor or ‘inner limit’ for a ‘reasonable period of time for implementation’. The arbitrator

ruled that the ‘reasonable period of time for implementation’, as determined under Article 21.3(c),

should be: the shortest period possible within the legal system of the Member to implement the

recommendations and rulings of the DSB. The arbitrator also noted that, when implementation does

not require changes in legislation but can be effected by administrative means, the reasonable period

of time ‘should be considerably less than 15 months. Article 21.2 of the DSU requires that, in

determining the ‘reasonable period of time for implementation’, particular attention should be paid to

matters affecting the interests of developing-country Members (maybe provide additional period).

Article 21.5 (compliance proceeding)- any disagreement as to (1) the existence of measures taken to

comply with the recommendations and rulings or (2) the WTO consistency of these measures, shall be

settled through proceedings which are provided for in Article 21.5 of the DSU.

Amicus Curiae Briefs: On the basis of Articles 11 (objective assessment of matter), 12 (panel can

develop its own working procedures) and 13 (panel can seek’ information and technical advice from

‘any individual or body’) of the DSU, the Appellate Body thus came to the conclusion in US –

Shrimp (1998) that panels have the authority to accept and consider amicus curiae briefs. EC

Asbestos (2001)- adopted an Additional Procedure to deal with amicus curiae briefs which the

12

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

division expected to receive in great numbers in that dispute. This Additional Procedure set out

substantive and procedural requirements to be met by any person or entity, other than a party or a third

party to this dispute, wishing to file a written brief with the Appellate Body. The Additional Procedure

provided, for example, for a requirement to apply for leave to file, and for a maximum page limit

(twenty) on the amicus curiae briefs that would be allowed to be filed.

Case Law:

Australia – Automotive Leather II Article 21.5

Facts: In WTO subsidies are prohibited. Australia gave a subsidy to some company, US challenged it.

Ruling- removal of the offending measure. Australian government asked the company to pay back the

subsidy, there was some conflict over the interest rate.US felt the implementation was incorrect.

Issue: execution litigation (Art. 21.5).

Holding: WTO rulings are prospective in nature. This does not work in the case of subsidies. The way

to remedy the subsidy is to refund the subsidy, retrospective remedies are allowed.

Analysis: This amounted to making inroad into domestic constituencies, making them unhappy.

However, the WTO not concerned with domestic constituencies.

Lead Acid Batteries Case:

Facts: The dumping allegation brought by U.S., India and Brazil against Bangladesh exporters.

Bangladesh objected to these allegations. Readymade garment, frozen food, lead batteries were being

exported. Selling a product at a lower price in the importer’s market damaging the domestic business

is called dumping. If the export is below than 3% then the export is negligible and difficult to classify

as dumping. India imposed on a duty on the weight of the batteries.

Result: Bangladesh, LDC, difficulties in accessing WTO dispute resolution- resource crunch.

Exporting/interested Company provided for financial support and advisory centre for legal support.

Some weak links in India’s case as well. All these factors led them to pursue WTO dispute resolution.

Political consideration- WTO dispute resolution process usually pursued. India will still find

Bangladesh to be a lucrative trading partner. India agreed to settle the issue during WTO consultation

because of the weak legal position. Bangladesh withdrew the case.

Analysis: The reading highlights difficulties faced by LDC in pursuing such cases- financial, political

will (Art. 3 DSU- cases should not be considered as contentious) yet LDCs are scared. Bangladesh

minister met Indian minister, trying to settle the issue at government level. But then these government

level negotiations become side lined in view of the WTO mechanism, which has an overbearing

presence. Having the consultation mechanism helped Bangladesh and the weak legal position of India

helped Bangladesh in settling the issue before the adjudication stage. They came to a mutual

agreement where India admitted that Bangladesh has not dumped at all. This shows the power of the

dispute resolution system. However, if the case had reached the adjudication stage and Bangladesh

had won the case and if India refused to follow the ruling, Bangladesh as LDC would not be able to

retaliate against India. A solution is proposed that all LDC retaliate, but difficult to build such

consensus. First LDC country to become a complainant. India also wanted to protect its reputation as

a champion of the poor countries.

IV. Trade Remedies

Anti-Dumping

History- (1) WTO law on dumping and anti-dumping measures is set out in Article VI of the GATT

1994 and in the WTO Agreement on Implementation of Article VI of the GATT 1994, commonly

referred to as the Anti-Dumping Agreement. (2) When the GATT was negotiated in 1947, participants

initially failed to agree on whether a provision allowing countries to impose anti-dumping measures in

response to dumping should even be included. However, largely at the insistence of the United States,

Article VI was included to provide a basic framework as to how countries could respond to

dumping. (3) In the years following its negotiation, Article VI alone proved to be inadequate in

addressing the anti-dumping measures. Its language was particularly vague and was therefore

interpreted and applied in an inconsistent manner. (4) At the end of the Uruguay Round, a

compromise was reached that was ultimately reflected in the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement and

which, together with Article VI of the GATT 1994, sets out the current rules on dumping and anti-

dumping measures. (5) Developing countries are against the idea. The export price is lower of the

13

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

dumped goods. because of factors like low demand in local market and lack of economies of scale. (6)

These are not retaliatory measures. It is an act of protecting domestic industry. Hence, regulated. But

why allow protectionism? Political reason- US made proposals for liberalization but US domestic

industry was against it. The countervailing duty served as a mechanism to pacify them. If you are

unable to compete with imports, we have the anti-dumping duty to help you.

Definition: ‘Dumping’ is a situation of international price discrimination involving the price and cost

of a product in the exporting country in relation to its price in the importing country. Article VI of the

GATT 1994 and Article 2.1 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement define dumping as the introduction of a

product into the commerce of another country at less than its ‘normal value’. Thus, a product can be

considered ‘dumped’ where the export price of that product is less than its normal value, that is, the

comparable price, in the ordinary course of trade, for the ‘like product’ destined for consumption in

the exporting country.

Triggering of the Anti-Dumping Measure: Pursuant to Article VI of the GATT 1994 and the Anti-

Dumping Agreement, WTO Members are entitled to impose anti-dumping measures if, after an

investigation initiated and conducted in accordance with the Agreement, on the basis of pre-existing

legislation that has been properly notified to the WTO, a determination is made that: (1) there is

dumping; (2) the domestic industry producing the like product in the importing country is suffering

injury (or threat thereof) Article 3; and (3) there is a causal link between the dumping and the injury

(Article 3.5).

Anti-Dumping Measures: Article VI, and in particular Article VI:2, read in conjunction with

the Anti-Dumping Agreement, limits the permissible responses to dumping to: (1) provisional

measures (provisional duty or, preferably, a security, by cash deposit or bond, equal to the amount of

the preliminarily determined margin of dumping Article 7); (2) price undertakings (Undertakings to

revise prices or cease exports at the dumped price Article 8); and (3) definitive anti-dumping duties (It

is desirable’ that the duty imposed be less than the margin of dumping if such lesser duty would

be adequate to remove the injury to the domestic industry Article 9).

Article 9.2 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement requires Members to collect anti-dumping duties on

a non-discriminatory basis on imports from ‘all sources’ found to be dumped and causing injury. The

MFN treatment obligation thus applies to the collection of anti-dumping duties.

Article 11 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement establishes rules governing the duration of anti-dumping

duties and a requirement for the periodic review of any continuing necessity for the imposition of

anti-dumping duties.

Investigation: The Anti-Dumping Agreement sets out, in considerable detail, how investigating

authorities of WTO Members have to initiate and conduct an anti-dumping investigation. Article 5-

initiation of an anti-dumping investigation; and Article 6 the conduct of an investigation.

Committee of Anti-Dumping Practices: Article 16.4 requires Members to report all preliminary or

definitive anti-dumping actions taken. They also have to submit, on a half-yearly basis, reports on any

anti-dumping actions taken within the preceding six months. In accordance with Article 16.5, each

Member has to notify the Committee which of its authorities are competent to initiate and conduct

investigations and domestic procedures governing such investigations.

Case Law:

US – Continued Dumping and Subsidy Offset Act, 2000

In US – Offset Act (Byrd Amendment) (2003), the measure at issue was the United States Continued

Dumping and Subsidy Offset Act of 2000 (CDSOA). This Act provided, in relevant part, that United

States Customs shall distribute duties assessed pursuant to an anti-dumping duty order to ‘affected

domestic producers’ for ‘qualifying expenditures’. Recalling its ruling in US – 1916 Act (2000) that

Article VI:2, read in conjunction with the Anti-Dumping Agreement, limits the permissible responses

to dumping to definitive anti-dumping duties, provisional measures and price undertakings. The

14

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

Appellate Body concluded in US – Offset Act (Byrd Amendment) (2003) is inconsistent with Article

18.1 of Anti-Dumping Agreement. Article 18.1 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement provides: No specific

action against dumping of exports from another Member can be taken except in accordance with the

provisions of GATT 1994, as interpreted by this Agreement.

Subsidies:

Debate: On the one hand, subsidies are evidently used by governments to pursue and promote

important and fully legitimate objectives of economic and social policy. On the other hand, subsidies

may have adverse effects on the interests of trading partners whose industry may suffer, in its

domestic or export markets, from unfair competition with subsidised products.

History: (1) The WTO rules on subsidies and subsidised trade are set out in Articles VI and XVI of

the GATT 1994 but also, and more importantly, in the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and

Countervailing Measures, commonly referred to as the SCM Agreement. (2) The GATT 1947 did not

contain clear and comprehensive rules on subsidies. In fact, Article XVI of the GATT 1947, entitled

‘Subsidies’, did not even define the concept of ‘subsidies’. (3) Moreover, with regard to subsidies in

general, Article XVI merely provided that Contracting Parties to the GATT should notify subsidies

that have an effect on trade and should be prepared to discuss limiting such subsidies if they cause

serious damage to the interests of other CONTRACTING PARTIES. (4) With regard to export

subsidies, Article XVI provided that CONTRACTING PARTIES were to ‘seek to avoid’ using

subsidies on exports of primary products. In 1962, Article XVI was amended to add a provision

prohibiting CONTRACTING PARTIES from granting export subsidies to non-primary products

which would reduce the sales price on the export market below the sales price on the domestic

market. Note, however, that this amendment did not apply to developing countries. (5) In addition,

Article VI of the GATT 1947, which dealt with measures taken to offset any subsidy granted to an

imported product (i.e. countervailing duties), did not provide for clear and comprehensive rules. (6)

The Uruguay Round negotiations eventually resulted in the SCM Agreement.

Definition: Article 1.1 of the SCM Agreement defines a subsidy as a financial contribution by a

government or public body which confers a benefit. Furthermore, Article 1.2 of the SCM

Agreement provides that the WTO rules on subsidies and subsidised trade only apply to ‘specific’

subsidies, i.e. subsidies granted to an enterprise or industry, or a group of enterprises or industries.

Subsidies v. Dumping: WTO law permits the imposition of anti-dumping measures if dumping

causes injury. The WTO law on subsidies is different. Article XVI of the GATT 1994 and Articles 3 to

9 of the SCM Agreement impose disciplines on the use of subsidies. Certain subsidies are prohibited,

and many other subsidies, at least when they are specific, rather than generally available, may be

challenged when they cause adverse effects to the interests of other Members. WTO law distinguishes

between prohibited subsidies, actionable subsidies and non-actionable subsidies. Each of these kinds

of subsidy has its own substantive and procedural rules. Moreover, subsidies on agricultural products

are subject to specific rules set out in the Agreement on Agriculture.

Response to Dumping: Members may, pursuant to Article VI of the GATT 1994 and Articles 10 to 23

of the SCM Agreement, respond to subsidised trade which causes injury to the domestic industry

producing the like product by imposing countervailing duties on subsidised imports. These

countervailing duties are to offset the subsidisation. However, comparable to the anti-dumping

measures discussed above, countervailing duties may only be imposed when the relevant investigating

authority properly establishes that there are subsidised imports, that there is injury to a domestic

industry and that there is a causal link between the subsidised imports and the injury. As with the

conduct of anti-dumping investigations, the conduct of countervailing investigations is subject to

relatively strict procedural requirements. Note that the substantive and procedural rules on the

imposition and maintenance of countervailing measures are similar to (albeit somewhat less detailed

than) the equivalent rules on anti-dumping measures).

Conditions for Imposing Countervailing Measures: It follows from Article VI of the GATT 1994

and Articles 10 and 32.1 of the SCM Agreement that WTO Members may impose countervailing

15

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

duties when three conditions are fulfilled, namely: (1) there are subsidised imports, i.e. imports of

products from producers who benefited or benefit from specific subsidies within the meaning of

Articles 1, 2 and 14 of the SCM Agreement; (2) there is injury to the domestic industry of the like

products within the meaning of Articles 15 and 16 of the SCM Agreement; and (3) there is a causal

link between the subsidised imports and the injury to the domestic industry and injury caused by other

factors is not attributed to the subsidised imports.

Subsidies Committee: Article 25.11 provides that Members shall report without delay to the

Subsidies Committee all preliminary or final actions taken with respect to countervailing duties as

well as submit semi-annual reports on any countervailing duty actions taken within the preceding six

months.

Case Law:

US – Large Civil Aircraft (2nd complaint) (2012)

Issue: In US – Large Civil Aircraft (2nd complaint) (2012), the Appellate Body addressed the

question of whether the reduction in the Washington State business-and-occupation tax rate applicable

to commercial aircraft and component manufacturers constitutes the foregoing of revenue otherwise

due within the meaning of Article 1.1(a)(1)(ii) that would constitute subsidy.

Holding: The Panel must be aware of the limitations inherent in identifying and comparing a general

rule of taxation, and an exception from that rule. For instance, we noted that it could be misleading to

identify a benchmark within a domestic tax regime solely by reference to historical tax rates.The

Appellate Body concluded in US – Large Civil Aircraft (2nd complaint) (2012) that it was satisfied

the panel had a proper basis for selecting as the benchmark the tax treatment generally applicable in

Washington State to businesses engaged in manufacturing, wholesaling, and retailing activities. In

addition, the Appellate Body considered that the panel properly concluded that a comparison of these

general tax rates to the lower tax rate that was applied to the gross income of commercial aircraft and

component manufacturers indicated the foregoing of government revenue otherwise due within the

meaning of Article 1.1(a)(1)(ii) of the SCM Agreement.

US-Carbon Steel (India)

AB held that PSUs do not constitute public body under Article 1.1 capable of providing subsidy

merely for reasons that the government has a majority shareholding in them and directors to the

Boards of PSUs are appointed by the government. AB held that cumulation of non-subsidized imports

(dumped products) with subsidized imposts while determining injury in countervailing duty

investigation is inconsistent with the WTO law (Article 15). The AB Report is also relevant with

regard to a number of other systemic issues concerning the implementation of ASCM. (1) For

instance, on the aspect of determining an appropriate benchmark to determine benefit, it has now been

clarified that investigating authorities cannot presumptively reject government-related prices as

relevant benchmarks as indicators of prevailing market conditions; (2) in applying adverse inferences

against non-cooperating parties, investigating authorities cannot arbitrarily choose to apply any

inference, but instead account for all substantiated facts; and (3)in selecting one fact over another in

such cases, the finding is to be supported by reasoning and evaluation.

US – Carbon Steel (Germany)

Article 11. 9 does not reflect a concept that subsidization at less than a de minimis (i.e. less than 1 per

cent ad valorem) threshold can never cause injury. For us, the de minimis standard in Article 11.9 does

no more than lay down an agreed rule that if de minimis subsidization is found to exist in an original

investigation, authorities are obliged to terminate their investigation, with the result that no

countervailing duty can be imposed in such cases.

A. Non-Discrimination under WTO law:

Why non-discrimination:

1) Discrimination in matters relating to trade breeds resentment and poisons the economic and

political relations between countries.

2) Discrimination makes scant economic sense as, generally speaking, it distorts the market in

favour of goods and services that are more expensive and/or of lower quality.

Non-discrimination in WTO law and Policy:

16

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

- Preamble of WTO agreement: The concept of non-discrimination is enshrined in the WTO

agreement as one among two of the means of achieving the objectives of WTO. It states,

‘elimination of discriminatory treatment in international trade relations’ contributes to the

achievement of the objects stated in the preamble of WTO agreement.

- Two Forms of Discrimination- MFN and National Treatment

I. Most Favoured Nation

- Legal Provisions: Article I para 1 of GATT and Article II para 1 of GATS

- There are multiple MFN like obligations in other articles of GATT- example chapeau of

article XX, TBT, SPS etc.- this shows the pervasive nature of MFN obligations.

Article I para 1 of GATT:

- Principle obligation under WTO- EC – Tariff Preferences (2004).

- Do not discriminate between your trading partners with regard to like products- equality of

opportunity

- Imports+Exports

- Apply at the border and inside the border

- Determination of likeness is essential to the MFN doctrine

- Discrimination can be: a) de jure or b) de facto-origin neutral measures

- Three elements of Article I para 1: 1) Advantage, 2) are the products like and 3) immediately

and unconditionally

De jure v. De facto discrimination:

- In Canada – Autos (2000), the Appellate Body rejected, as the panel had done, Canada's

argument that Article I:1 does not apply to measures which appear, on their face, to be

‘origin-neutral’ vis-à-vis like products. According to the Appellate Body, measures which

appear, on their face, to be ‘origin-neutral’ can still give certain countries more opportunity to

trade than others and can, therefore, be in violation of the non-discrimination obligation of

Article I:1. The measure at issue in Canada – Autos (2000) was a customs duty exemption

accorded by Canada to imports of motor vehicles by certain manufacturers. Formally

speaking, there were no restrictions on the origin of the motor vehicles that were eligible for

this exemption. In practice, however, the manufacturers imported only their own make of

motor vehicle and those of related companies. As a result, only motor vehicles originating in a

small number of countries benefited de facto from the exemption.

- De facto more popular than de jure due to crafty drafting of legislations and regulations.

Advantage:

- Advantage= favour, privilege or immunity (mentioned in Article 1: para 1.

- Includes: (1) customs duties; (2) charges of any kind imposed on importation or exportation;

(3) charges imposed on the international transfer of payments for imports or exports; (4) the

method of levying such duties and charges; (5) all rules and formalities in connection with

importation and exportation; (6) internal taxes or other internal charges (Article III:2); and (7)

laws, regulations and requirements affecting internal sale, (Article III:4).

- The panel and AB in EC – Bananas III (1997) considered that a measure granting an

‘advantage’ within the meaning of Article I:1 is a measure that creates ‘ more favourable

competitive opportunities’ or affects the commercial relationship between products of

different origins.

- Canada – Autos (2000)- The term ‘advantage’ in Article I:1 refers to any advantage granted

by a Member to any like product from or for another country.

- No balancing possible i.e. cant give advantage in one and disadvantage in other- US footwear

case.

Like Product:

- Not defined in GATT

- The Appellate Body in EC – Asbestos (2001) considered that the dictionary meaning of ‘like’

suggests that ‘like products’ are products that share a number of identical or similar

characteristics.

17

Downloaded by Liza (huynhtramminhthu@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5931387

- Test laid down in Canada- Aircraft case: (1) which characteristics or qualities are important

in assessing ‘likeness’; (2) to what degree or extent must products share qualities or

characteristics in order to be ‘like products’; and (3) from whose perspective ‘likeness’ should

be judged.

- The term like is not uniform in all GATT provisions- the context in which it is used must be

examined.

- It is reasonable to expect that this case law regarding Article III will inform the interpretation

of the concept of ‘like products’ in Article I:1.