Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trend in Dry Eye

Uploaded by

Anonymous tqCuM5rbVUCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trend in Dry Eye

Uploaded by

Anonymous tqCuM5rbVUCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

REVIEW

Trends in Dry Eye Disease Management

Worldwide

This article was published in the following Dove Press journal:

Clinical Ophthalmology

Mohamed Mostafa Hantera Abstract: Dry eye disease (DED) is a condition frequently encountered in ophthalmology

practice worldwide. The purpose of this literature review is to highlight the worldwide

Department of Ophthalmology, Umm AL

Qura University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia trends in DED diagnosis and therapy amongst practitioners and determine if a more

uniform approach to manage this multifactorial condition has developed over the past

two decades. A manual literature search utilizing PubMed was conducted to obtain papers

with survey results relating to ophthalmology and optometry diagnosis and treatment of dry

eye from January 2000 to January 2020. This did not include data from clinical trials as we

were only interested in community clinical practice trends. The terms “dry eye” and

“survey” were searched in combination with one or more of the following words or

phrases: prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, therapy, etiology, risk factors, therapy, and

quality of life. Papers were selected based on their direct applicability to the subject and

were only included if they contained relevant survey data from community practitioners.

The available literature suggests common trends worldwide in the diagnosis and treatment

of DED. These trends have not modified substantially over the past two decades.

Practitioner education on the benefits of measuring tear film homeostasis could increase

its use as a diagnostic tool to complement current tools. Of the results found, 75% of the

papers were published after 2006 and only one paper after 2017. More recent survey

results are required to determine if research into DED pathophysiology is altering the

current trend in DED management.

Keywords: dry eye disease, etiology, prevalence, therapy, survey

Introduction

This paper aims to investigate the trends among practitioners diagnosing and

treating DED around the world over the last two decades. The literature search

found 12 papers with survey results from eye care practitioners determining their

diagnostic and/or therapeutic management of DED. The literature comprises

research between January 2000 and November 2018 from 12 countries around

the world; Australia, Canada, Ghana, Italy, Japan, Korea, New Zealand (NZ),

Philippines, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom (UK) and the United States

(US). The surveys were sent out to community practitioners. We did not inves

tigate data from clinical trials as we felt there may be a bias towards different

diagnostic tools that may not accurately represent the trends amongst community

Correspondence: Mohamed Mostafa practitioners. The understanding of dry eye pathophysiology has advanced in the

Hantera

Medical Reference Center, King Road last decade and we wanted to determine if there has been a modified diagnostic

After Hiraa Crossing, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia and therapeutic approach among community practitioners to reflect this

Tel +966552553322

Email Mohamedhantera30@gmail.com knowledge.

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15 165–173 165

DovePress © 2021 Hantera. This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

http://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S281666

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). By accessing the work

you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For

permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms (https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php).

Hantera Dovepress

Overview of Dry Eye of DED.20 The Japanese Dry Eye Society (JDES) and Asia

The prevalence of dry eye disease in the population ranges Dry Eye Society (ADES) base their diagnostic criteria on this

from 5%-34% with large variations between countries.1–10 concept.20 The TFOD focuses on which part of the tear film

The large discrepancy in prevalence worldwide is pre is abnormal so a' tear-film oriented therapy' (TFOT) can be

sumed to be the result of a combination of factors; geo initiated.20

graphical location, study population variations and lack of

consistent diagnostic criteria.10 Treatment

In mild DED the eye will often respond favourably to

Definition treatment.21 With prolonged damage goblet cell repair

It is now widely understood that the cause for DED is multi mechanisms can fail resulting in irregular mucin produc

factorial and directly affects the interpalpebral ocular surface tion. A so-called “Vicious Circle” will be established and

and tear film, leading to discomfort and disturbance in vision. lead to permanent damage if left untreated.21

The updated report in 2017 from the Tear Film and Ocular The available treatments for DED have advanced over the

Surface Society (TFOS) International Dry Eye Workshop II past couple of decades, despite this, traditional methods of

(DEWS II) defined DED as „a multifactorial disease of the warm compresses and artificial tears remain a universal first

ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the line therapy.22 Second line treatments include tea tree oil

tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which therapy for Demodex, punctal plugs, moisture chamber

tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface devices, ointment overnight, intense pulsed light therapy,

inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities topical corticosteroids, antibiotics, non-glucocorticoid

play etiological roles.„11 The TFOS DEWS II best-practice immunomodulators (cyclosporine), LFA-1 antagonist drugs

guideline is designed to help facilitate a consistent approach (lifitegrast), purinergic P2Y2 receptor agonists (diquafosol),

among practitioners managing DED.12 oral and topical hyaluronic acid (HA) and oral tetracycline

antibiotics.23–25 (Table 1)

Diagnosis

Symptoms Results

There is a poor correlation between DED signs and This paper looks at the current trends in diagnosis and

symptoms.13–16 For this reason a validated patient question management of DED among community eye care practi

naire may be more useful to observe any change in symptoms tioners worldwide. Of the 12 papers we found with relevant

over time rather than as a tool for initial diagnosis.10 survey results, 75% had been published since 2007 when

the TFOS DEWS first reported tear hyperosmolarity as

Signs a central mechanism in DED. The surveys were sent out

Clinical signs are assessed by evaluating the layers of the to community practitioners. In some cases the respondents

tear film, surrounding lids and interpalpebral zone. In 2010 reported an interest in dry eye and/or anterior segment.

Sullivan et al found the diagnostic tools most commonly Some survey respondents were affiliated with a University

used in grading severity were symptomatology, tear break but the majority were in private community practice. For

up time (TBUT), fluorescein or lissamine green staining of this reason we did not obtain a grade or rank for the respon

the cornea and conjunctiva, meibomian secretion scoring dents. We did not want to include data from clinical trials

and the Schirmer test.17 As early as 2006, Tomlinson et al where there may be a bias towards specific diagnostic tools.

concluded that the measurement of tear film osmolarity The survey results over the past two decades provide

arguably offers the best means of capturing, in a single a summary of clinical practice preferences among practi

parameter, the balance of input and output of the lacrimal tioners in the community across 12 countries. (Table 2).

system.18 In April 2007 the TFOS DEWS report regarded

tear hyperosmolarity as the central mechanism causing Discussion

ocular surface inflammation and the initiation of compen At the beginning of this century practitioner survey results

satory events in dry eye, this was corroborated in 2017.11,19 indicated the use of multiple tools to evaluate DED.26

This research supports a ‘tear-film oriented diagnosis’ Largely there was poor satisfaction with the available

(TFOD) that looks at the tear secretion volume, tear stability, diagnostic and therapeutic options for dry eye and research

lipid layer thickness and vital staining to evaluate the cause in 2005 recommended a systematic review into dry eye

166 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15

DovePress

Dovepress Hantera

Table 1 Summary of Therapies for Dry Eye Disease22–25 A systematic review in 2018 of dry eye-specific ques

Treatment Therapies tionnaires was conducted and despite identifying 13 vali

Strategy dated questionnaires, they all had limitations and there was

not one standardized DED-specific questionnaire.37

First line therapy Warm compresses, lid hygiene

Artificial tear supplements Consequently future research is required to formulate

Patient education a DED questionnaire that focuses on normative data and

Modification of environment can detect clinically significant changes in response to

Dietary modification treatment.37

Second line Tea tree oil therapy for Demodex

therapy Punctal plugs Survey Results

Moisture chamber devices Patient history is an imperative diagnostic tool and our

Ointment overnight review confirms the majority of practitioners surveyed under

Intense pulsed light therapy stand this and routinely use it for diagnosis.12,27,28,30–35

Topical corticosteroids

Perhaps education around the use of a DED questionnaire

Topical Antibiotics

Oral secretagogues

to document and more easily evaluate disease progression

Serum eye drops and management is warranted. Further research into a “gold

Therapeutic contact lens options standard” questionnaire that is routinely used around the

Non-glucocorticoid immunomodulators world will likely provide a consistent approach to under

(cyclosporine) standing symptoms and treatment response.

LFA-1 antagonist drugs (lifitegrast)

Oral tetracycline antibiotics

Oral and topical hyaluronic acid Investigations

Purinergic P2Y2 receptor agonist (diquafosol) The most appropriate diagnostic tools currently recom

Amniotic membrane grafts mended by the TFOS DEWS II are symptoms, NIBUT,

In office Intense pulsed light therapy osmolarity and ocular surface staining.36 In contrast the

procedures Vectored thermal pulsation JDES/ADES diagnosis of dry eye relies on patient symp

Meibomian gland probing toms and a reduction in TBUT without the inclusion of the

BlephEx™

Schirmer’s value or the presence of epithelial damage.20,38

The new concept of TFOD and TFOT adopted in Asian

countries is based on the dynamics of the precorneal tear

tools and their validity.27 Reinforcing this in 2007 Kim film. This concept implies the use of FBUT is all that is

et al found 39.8% practitioners felt the need for a new needed to classify DED and to propose appropriate therapy

diagnostic method to evaluate the stability of the tear film based on the instability of the tear film.38 This view is very

and its layers.28 More recently there remains consensus useful and practical for clinicians.

among practitioners that DED is multifactorial in nature

and no one diagnostic tool suits all patients.12,29–31 Tear Film Stability

The three-layer physiology of the tear film first described

last century by Wolff is still utilized: a mucin layer cover

History and Symptoms ing the epithelial cells of the cornea; an aqueous layer to

Over the past two decades, we found an overwhelming provide lubrication and nutrients to maintain osmolarity;

diagnostic trend that placed clear emphasis on patient and a lipid layer to prevent evaporation.39

history and symptoms.12,27,28,30–35 A validated symptom

questionnaire can be administered at the beginning of Tear Layer Evaluation

each examination to monitor the progression and effi The aqueous layer quantity can be evaluated using the

cacy of treatment.36 The Ocular Surface Disease Index Schirmer test, the strip meniscometry and anterior segment

(OSDI) is the most widely used questionnaire for DED optical coherence tomography.20 Lipid interferometry is

clinical trials.36 The JDES/ADES consensus also con available to evaluate the lipid layer.20 There is no simple

firms symptom assessment as a fundamental tool for evaluation method readily available to evaluate mucins on

diagnosis.37 the ocular surface.20 Vital staining using fluorescein and

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15 167

DovePress

Hantera Dovepress

Table 2 Summary of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Trends Among Community Eye Care Practitioners Surveyed in the Past Two

Decades

Countries Clinical Paper (Year) Countries Diagnostic Tools Most Frequently Used Mainstay of Treatment (% of

as First Choice (% of Respondents) Respondents)

Australia, Canada, Korb. Survey of Preferred Tests for Diagnosis Dry eye questionnaires (and/or history) (28%)

Italy, Japan, of the Tear Film and Dry Eye (2000)26 Fluorescein break up time (FBUT) (19%)

Switzerland, Ocular surface stain (13%)

United Kingdom, Schirmer test (9%)

United States

Australia, United Turner et al Survey of eye practitioners’ History – rated 8.5/10 for diagnosis

Kingdom attitudes towards diagnostic tests and FBUT – rated 7/10 for diagnosis

therapies for dry eye disease (2005)27

Korea Kim et al Status of diagnosis and treatment of Decreased FBUT (42.6%) Top three treatments for each level of

patients with dry eye in Korea by survey Symptoms (37.1%) severity:

(2007)28 Schirmer test (13.2%) Level 1 – preserved artificial tear substitutes

(35.9%); environmental management (31.3%);

lid hygiene (12.5%);

Level 2 - non-preserved artificial tear

substitutes (19.1%); gels and ointments

(17.6%); environmental management (17.5%);

Level 3: non-preserved artificial tears

(17.5%); gels and ointments (15.4%); anti-

inflammatory agent (13.1%);

Level 4: – non-preserved artificial tears

(13.5%); gels and ointments (13.4%); punctal

plug (12.1%)

United States Asbell et al Ophthalmologist perceptions Primarily lubrication with artificial tears

regarding treatment of moderate to severe For more moderate to severe use of multiple

dry eye: results of a physician survey (2009)29 therapies

Spain Carona et al Knowledge and Use of Tear Film Preference #1: TBUT – optometrists (56.4%)

Evaluation Tests by Spanish Practitioners and ophthalmologist (41.8%)

(2011)33 OR Schirmer test – optometrists (21.4%) and

ophthalmologists (26.2%)

Preference #2: TBUT – optometrists (39.3%)

and ophthalmologists Schirmer test (35%)

Philippines Echavez et al Survey on the Knowledge, Most valuable tests ranked: Most valuable treatments ranked:

Attitudes, and Practice Patterns of 1 TBUT (90%) 1 Artificial tear substitutes (100%)

Ophthalmologists in the Philippines on the 2 Fluorescein corneal stain (91%) 2 Lid hygiene (88%)

Diagnosis and Management of Dry Eye 3 Schirmer test (70%)

Disease (2013)34 4 Meibomian gland evaluation (84%)

5 Patient symptoms (99%)

12 Tear osmolarity (6%)

Australia Downie LE, Keller PR, Vingrys AJ. An Most valuable tests ranked: Artificial tear substitutes – non-preserved

Evidence-Based Analysis of Australian 1 Symptom assessment (62.6%) Lid hygiene

Optometrists’ Dry Eye Practices (2013)30 2 FBUT (35.3%)

3 Meibomian gland evaluation (27.5%)

Tear osmolarity (<10%)

United States Williamson et al Perceptions of Dry Eye History and symptoms (69.7%) (measure of Artificial tear substitutes – non-preserved

(North Carolina) Disease Management in Current Clinical therapeutic effect) (80.8%)

Practice (2014)35 FBUT (47%) Lid hygiene (15.2%)

Ocular surface stain – fluorescein (39%)

Tear osmolarity (2%)

(Continued)

168 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15

DovePress

Dovepress Hantera

Table 2 (Continued).

Countries Clinical Paper (Year) Countries Diagnostic Tools Most Frequently Used Mainstay of Treatment (% of

as First Choice (% of Respondents) Respondents)

Australia and the Downie et al Comparing self-reported Results averaged across countries: Patient Mild – non-preserved artificial tear

United Kingdom optometric dry eye clinical practices in symptoms (61%) substitutes (74.5%) and lid hygiene (70%)

Australia and the United Kingdom: is there Meibomian gland evaluation (59.6%) Moderate to severe – first two treatments

scope for practice improvement? (2016)31 FBUT (56.2%) remain non-preserved artificial tear

Conjunctival stain (49.9%) substitutes and lid hygiene with additional

Tear osmolarity (<8%) non-preserved gels being the third choice

Ghana Asiedu et al Survey of Eye Practitioners’ TBUT – optometrist (62%); ophthalmologist Aqueous based artificial tears optometrists

Preference of Diagnostic Tests and Treatment (65%) (66.2%) ophthalmologist (85%) and lipid

Modalities for Dry Eye in Ghana (2016)32 Patient history – optometrist (31%); based artificial tears optometrists (21.8%)

ophthalmologist (35%) and ophthalmologists (15%)

Tear osmolarity (0%)

New Zealand Xue AL, Downie LE, Ormonde SE & Craig JP. Patient symptoms Mild: Non-preserved artificial tear

A comparison of the self-reported dry eye Meibomian gland evaluation substitutes optometrists (74%)

practices of New Zealand optometrists and Corneal and conjunctival fluorescein stain ophthalmologists (72%) and lid hygiene

ophthalmologists (2017)12 FBUT optometrists (74%) and ophthalmologists

Tear osmolarity (<5%) (62%)

Moderate: eyelid hygiene

optometrists (90%) ophthalmologists (76%)

and non-preserved lubricant drops

optometrists (86%) ophthalmologists (86%)

and gels optometrists (71%) and

ophthalmologists (45%).

-Severe: addition of oral tetracyclines,

corticosteroids, oral omega-3 fatty acid

supplements

United States Bunya et al A Survey of Ophthalmologists Corneal stain – fluorescein (62%)

Regarding Practice Patterns for Dry Eye and TBUT (49%)

Sjogren’s Syndrome (2018)41 Schirmer’s test (32%)

Tear osmolarity (18%)

lissamine green can be used to evaluate the epithelial breakup pattern can also be used to confirm the abnorm

layer.20 alities in each component of the tear film.20 FBUT is easy

In addition, lid wiper epitheliopathy (LWE) is observed to perform but due to the potential introduction of water to

as vital staining of the upper and lower lid margin directly the ocular surface at the time of measurement, lipid layer

in contact with the ocular surface. The primary cause for interferometry, grid xeroscope, and tear stability analysis

lid wiper epitheliopathy is thought to be friction between systems may result in a more accurate tear film

the ocular surface and the lid wiper related to inadequate assessment.20

lubrication.40 The presence of LWE in conjunction with

reduced FBUT indicate a reduction in tear film quantity. Tear Osmolarity

Research indicates tear osmolarity demonstrates the high

Tear Break Up Time est correlation to disease severity of all clinical DED

Measurement of the tear break up time with a non-invasive tools.36 In six out of seven papers published since 2012

technique (NIBUT) is considered preferable to fluorescein tear osmolarity was included as a diagnostic tool but less

break up time (FBUT). The JDES/ADES consensus con than 10% of respondents used it to aid their

cludes FBUT is a useful tool for evaluating tear film diagnosis.12,30–32,34,35 In 2018 Bunya et al confirmed

stability and can easily be performed.20 Fluorescein 18% of surveyed practitioners reported evaluating tear

break up time can be used to analyse the aqueous layer, osmolarity for diagnosis.41 However corroborating with

lipid layer, and epithelial layer, and the fluorescein Korb in 2000 they found that practitioners still preferred

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15 169

DovePress

Hantera Dovepress

traditional dry eye tests.41 Technology for assessing tear DED then step 4 of the guidelines indicates topical corti

osmolarity is becoming widely available and we may see costeroids for longer duration, amniotic membrane grafts,

practitioners adopting this modality for in-office diagnosis. surgical punctal occlusion or other surgical approaches.43

It is hoped that survey data in the years to come will

determine if practitioners are now routinely including tear Drug Therapy

osmolarity measurements in their battery of diagnostic Topical corticosteroids have been used for years to treat

tests. the inflammation associated with dry eye.44 Topical

cyclosporine A is a common second line therapy for

Ocular Staining those that have had little success with the first line more

Ocular surface staining may be considered a late sign of conservative measures.22 In July 2016, lifitegrast 5%

DED and an indication of disease severity in severe DED. became the second FDA approved topical ocular anti-

The current TFOS DEWS II recommendation is to use inflammatory drug for the treatment of DED.

a combination of fluorescein and lissamine green to indi Although there has been a link between low dietary

cate ocular surface damage in severe DED. More recent intake of omega-3 essential fatty acids and DED, there are

papers found Lissamine green staining was rarely used for only a limited number of random controlled trials confirm

DED severity detection despite the fact that it is part of the ing supplementation improves tear break up times and

TFOS DEWS II severity grading scale.12,41 Schirmer scores.44

Hyaluronic acid has been proven to promote corneal

Survey Results epithelial wound healing.45 A pilot study by Kim et al in

Our review highlights patient symptoms, a combination of 2019 indicated both oral and topical HA were effective at

FBUT, meibomian gland evaluation and ocular surface reducing corneal fluorescein staining especially when used in

stain continue to be the predominant clinical tools used combination.24

to diagnose dry eye.12,28,30–35,41,42 This aligns with TFOS Aqueous secretagogue eye drops, topical 3% diquafo

DEWS II and JDES/ADES guidelines. However assess sol have become widely available for dry eye patients.25

ment of tear performance in its natural state was not They have been found to improve tear production, tear

frequently utilized with practitioner responses from break up time, and reduce corneal fluorescein and rose

a survey in 2017 in New Zealand reporting only 2% bengal staining and subjective symptoms.25

used LWE, corneal topography mire quality and non-

invasive TBUT.12 Procedures

Alongside drug therapies in-office procedures have

Treatment evolved targeting meibomian gland expression and

Effective treatment of dry eye is reliant on an accurate restoration of the natural flow of meibum (intense pulse

diagnosis. Targeting each abnormality in the TFOD light, vectored thermal pulsation, meibomian gland prob

approach will enhance treatment. The 2017 TFOS DEWS ing, BlephEx™).22

II provides guidelines for a stepped management and treat

ment protocol for dry eye.43 Survey Results

Step one involves patient education, modification of envir Given the extensive research and development into new

onment, dietary modification, ocular lubricants (if MGD therapeutic options for the treatment of DED we antici

then lipid containing supplements) and lid hygiene.43 If pated a modified treatment approach among practitioners.

these first line treatments are inadequate then in step two Where the more traditional treatments work to address the

non-preserved lubricants, tea tree oil for Demodex, punctal symptoms and restore the ocular surface, the newer ther

occlusion, moisture chamber googles, in-office physical apeutic modalities endeavour to reverse the primary cause

heating and expression of the meibomian glands, IPL, of the DED (such as inflammation).

topical antibiotic and/or corticosteroids, secretagogues, In this literature review the general trend among practi

immunomodulatory drugs, oral tetracyclines and topical tioners did follow a stepwise treatment approach. Mild dry eye

LFA-1 antagonist drugs should be considered.43 Step was treated with non-preserved artificial tear substitutes com

three includes oral secretagogues, serum eye drops and bined with lid hygiene.12,28,30,31,34,35 Therapeutics for moder

therapeutic contact lens options. In severe unresponsive ate to severe dry eye meant the addition of non-preserved gels

170 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15

DovePress

Dovepress Hantera

or ointments and topical anti-inflammatories.12,28,30,31, In advice from the TFOS DEWS II and JDES/ADES reports.

addition, it was found that the proportion of anti- Latest research is focusing on tear film biomarkers for dry

inflammatory drugs used increased with the treatment of eye disease, with tear osmolarity being one such biomar

moderate to dry eye.28 There seems to be consensus over the ker. It is thought that this may give a more quantitative

last twenty years that therapeutic management is based on measure of disease severity and therapeutic effectivity.

disease severity.12,28,31,34 Successful management can be Enhanced education about these newer diagnostic tools

determined by improvement of patient-reported symptoms identifying an imbalance in the tear film may alter DED

and a reduction in ocular signs. management over time.

Further tools measuring tear film quality such as LWE

Conclusion and non-invasive TBUT may become common practice as

Our literature search identified 12 published papers sur education continues to signify the importance of the

veying eye care practitioners in clinical practice about assessment of tear film performance in its natural state.

their diagnostic and/or therapeutic approach to dry eye. Therapeutic advancements in the treatment of DED

This limited number highlights the need for additional have not necessarily correlated with a modified treatment

worldwide research to determine practitioner trends. regime. Artificial tear supplements and lid hygiene con

Furthermore all but two of the surveys were extracted

tinue to be the first line treatment strategy, followed by

from research conducted prior to 2017 indicating a need

anti-inflammatory therapy for more moderate to severe

for current worldwide practitioner survey responses to

DED. In office treatments for meibomian gland expression

accurately determine trends in the coming years.

and restoration were not commonly reported in the man

The definition and classification of DED has advanced

agement strategy among surveyed respondents.

considerably over the past two decades due to an enhanced

Practitioner surveys are a sound way to gauge trends in

understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease. The

the professional population. Our literature review confirms

TFOS DEWS II and JDES/ADES provide definitions and

that the majority of community practitioners surveyed

guidelines for practitioners to follow. Both definitions

understand the multifactorial nature of DED and because

share the similar concept that disruption of the tears and

of this use multiple tools to form an accurate diagnosis.

ocular surface epithelia results in the development of

DED. The TFOS DEWS II definition included multiple The more recent literature also indicates an overall under

pathogeneses including ocular surface inflammation, tear standing that inflammation plays a critical role in DED and

film instability, hyperosmolarity and neurosensory the therapy for moderate to severe dry eye reflects this.

abnormalities. It focuses on the pathophysiology of But the reliable assessment of DED severity remains pro

DED. In contrast the JDES/ADES report highlights the blematic with often limited correlation between disease

importance of observations made by the practitioner. severity and clinical signs.

Despite differences, the consensus remains that careful Future practitioner surveys will determine if DED

consideration of symptoms and tear film status is required management is changing with time. Education on the

to accurately diagnose DED. importance of widespread use of the TFOS DEWS II and

Internationally there seems to be a common trend for JDES/ADES guidelines and algorithms in clinical practice

practitioners to routinely use the more traditional methods along with advancements in clinical research into tear film

of diagnosis. Subjectively patient symptoms remain biomarkers will further enhance the management strategy

a critical tool for diagnosis and assessment of treatment for dry eye disease.

effectivity. Research and education into the use of a “gold

standard” patient questionnaire will likely provide

Acknowledgments

a consistent approach to understanding symptoms and

I wish to acknowledge the assistance provided by Louise

response to treatment.

Wood, of EyeWrite Communications, in writing and edit

Objectively corneal staining with fluorescein and fluor

ing this paper.

escein tear break up time are the mainstay tools used

among the majority of practitioners surveyed worldwide.

Less consistency is seen with the use of non-invasive Disclosure

procedures to assess tear quality and osmolarity despite The author reports no conflicts of interest for this work.

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15 171

DovePress

Hantera Dovepress

21. Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G, Rolando M, Irkeç M.

References Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm.

Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(9):1168–1176. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-

1. Bakkar MM, Shihadeh WA, Haddad MF, Khader YS. Epidemiology 2013-304619

of symptoms of dry eye disease (DED) in Jordan: a cross-sectional 22. O’Neil E, Henderson M, Massaro-Giordano M, Bunya VY. Advances

non-clinical population-based study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. in dry eye disease treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30

2016;39(3):197–202. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2016.01.003 (3):166–178. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000569

2. Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Kheirkhah A, et al. Prevalence of dry 23. Şimşek C, Doğru M, Kojima T, Current Management TK. Treatment

eye syndrome in an adult population. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42 of dry eye disease. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2018;48(6):309-313.

(3):242–248. doi:10.1111/ceo.12183 doi:10.4274/tjo.69320

3. Lee AJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with dry eye 24. Kim Y, Moon CH, Kim B-Y, Jang SY. Oral hyaluronic acid supple

symptoms: a population based study in Indonesia. Br J Ophthalmol. mentation for the treatment of dry eye disease: a pilot study.

2002;86(12):1347–1351. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.12.1347 J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:5491626. doi:10.1155/2019/5491626

4. Moss SE. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch 25. Nam K, Kim H, Yoo A. A: efficacy and safety of topical 3%

Ophthalmol. 2000;118(9):1264–1268. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.9.1264 diquafosol ophthalmic solution for the treatment of multifactorial

5. Onwubiko SN, Eze BI, Udeh NN, Arinze OC, Onwasigwe EN, dry eye disease: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials.

Umeh RE. Dry eye disease: prevalence, distribution and determinants Ophthalmic Res. 2019;61(4):188–198. doi:10.1159/000492896

in a hospital-based population. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37 26. Korb DR. Survey of preferred tests for diagnosis of the tear film and

(3):157–161. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2013.09.009 dry eye. Cornea. 2000;19(4):483–486. doi:10.1097/00003226-

6. Sendecka M, Baryluk A, Polz-Dacewicz M. Prevalence and risk

200007000-00016

factors of dry eye syndrome. Przegl Epidemiol. 2004;58:227–233.

27. Turner AW, Layton CJ, Bron AJ. Survey of eye practitioners‘ atti

7. Uchino M, Nishiwaki Y, Michikawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk

tudes towards diagnostic tests and therapies for dry eye disease.

factors of dry eye disease in Japan: koumi study. Ophthalmology.

Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2005;33(4):351–355.

2011;118(12):2361–2367. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.029

doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01026.x

8. Vehof J, Kozareva D, Hysi PG, Hammond CJ. Prevalence and risk

28. Kim WJ, Kim HS, Kim MS. Current trends in the recognition and

factors of dry eye disease in a British female cohort. Br

treatment of dry eye: a survey of ophthalmologists. J Korean

J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(12):1712–1717. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-

Ophthalmological Soc. 2007;48(12):1614–1622. doi:10.3341/

2014-305201

jkos.2007.48.12.1614

9. Asbell P, Messmer E, Chan C, et al. Defining the needs and prefer

29. Asbell PA, Spiegel S. Ophthalmologist perceptions regarding treat

ences of patients with dry eye disease. BMJ Open Ophthalmol.

ment of moderate to severe dry eye: results of a physician survey.

2019;4(1):e000315. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2019-000315

Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2009;107:205-210.

10. Shanti Y, Shehada R, Bakkar MM, et al. Prevalence and associated

30. Downie LE, Keller PR, Vingrys AJ. An evidence-based analysis of

risk factors of dry eye disease in 16 northern West bank towns in

australian optometrists’ dry eye practices. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90

Palestine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):26.

(12):1385–1395. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000087

doi:10.1186/s12886-019-1290-z

31. Downie LE, Rumney N, Gad A, Keller PR, Purslow C, Vingrys AJ.

11. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition

Comparing self-reported optometric dry eye clinical practices in

and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276–283.

doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008 Australia and the United Kingdom: is there scope for practice

12. Xue AL, Downie LE, Ormonde SE, Craig JP. A comparison of the improvement? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36(2):140–151.

self-reported dry eye practices of New Zealand optometrists and doi:10.1111/opo.12280

ophthalmologists. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2017;37(2):191–201. 32. Asiedu K, Kyei S, Ayobi B, Agyemang FO, Ablordeppey RK. Survey

doi:10.1111/opo.12349 of eye practitioners’ preference of diagnostic tests and treatment

13. Nichols KK, Nichols JJ, Mph GL, Mitchell GL. The lack of associa modalities for dry eye in ghana. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39

tion between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. (6):411–415. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2016.08.001

Cornea. 2004;23(8):762-770. doi:10.1097/01. 33. Cardona G, Serés C, Quevedo L, Augé AM. Knowledge and use of

ico.0000133997.07144.9e tear film evaluation tests by spanish practitioners. Optom Vis Sci.

14. Aggarwal S, Galor A. What’s new in dry eye disease diagnosis? 2011;88(9):1106–1111. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182231b1a

Current advances and challenges. Faculty Rev. 2018;7:1952. 34. Echavez M. Lim bon siong r. survey on the knowledge, attitudes, and

15. Holland EJ, Darvish M, Nichols KK, Jones L, Karpecki PM. Efficacy practice patterns of ophthalmologists in the philippines on the diag

of topical ophthalmic drugs in the treatment of dry eye disease: nosis and management of dry eye disease. Philip J of Ophthal.

A systematic literature review. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(3):412–423. 2013;44:2.

doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2019.02.012 35. Williamson JF, Huynh K, Weaver MA, Davis RM. Perceptions of

16. Messmer EM. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry dry eye disease management in current clinical practice.

eye disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(5):71-82. doi:10.3238/ Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40(2):111–115. doi:10.1097/

arztebl.2015.0071 ICL.0000000000000020

17. Sullivan BD, Whitmer D, Nichols KK, et al. An Objective Approach 36. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic

to Dry Eye Disease Severity. Invest Opthalmology Visual Sci. Methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;544–579.

2010;51(12):6125–6130. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-5390 37. Shiraishi A, Sakane Y. Assessment of dry eye symptoms: current

18. Tomlinson A, Khanal S, Ramaesh K, Diaper C, McFadyen A. Tear trends and issues of dry eye questionnaires in Japan. Invest

film osmolarity: determination of a referent for dry eye diagnosis. Opthalmology Visual Sci. 2018;59(14):DES23–DES28. doi:10.1167/

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(10):4309–4315. doi:10.1167/ iovs.18-24570

iovs.05-1504 38. Shimazaki J. Definition and diagnostic criteria of dry eye disease:

19. Avialble from: https://www.tearfilm.org/dewsreport/pdfs/TOS-0502- historical overview and future directions. Invest Opthalmology Visual

DEWS-noAds.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2020. Sci. 2018;59(14):DES7–DES12. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-23475

20. Kojima T, Dogru M, Kawashima M, Nakamura S, Tsubota K. 39. Willcox MDP, Argüeso P, Georgiev GA, et al. TFOS DEWS II tear

Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of dry eye. Prog Retin Eye film report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):366–403. doi:10.1016/j.

Res. 2020;78:100842. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100842 jtos.2017.03.006

172 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15

DovePress

Dovepress Hantera

40. Efron N, Brennan N, Morgan P, Wilson T. Lid wiper epitheliopathy. 43. Jones L, Downie L, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and

Progress Retinal Eye Res. 2016;53:140–174. doi:10.1016/j. therapy report. Ocular Surface. 2017;15(3):575–628. doi:10.1016/j.

preteyeres.2016.04.004 jtos.2017.05.006

41. Bunya VY, Fernandez KB, Ying G-S, et al. Survey of 44. Buckley R. Assessment and management of dry eye disease. Eye.

Ophthalmologists Regarding Practice Patterns for Dry Eye and 2018;32(2):200–203. doi:10.1038/eye.2017.289

Sjogren Syndrome. Eye Contact Lens. 2018;44(2):196–201. 45. Ho W, Chiang T, Chang S, Chen Y, Hu F, Wang I. Enhanced corneal

doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000448 wound healing with hyaluronic acid and high-potassium artificial

42. Nichols KK, Nichols JJ, Zadnik K. Frequency of dry eye diagnostic tears. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2013;96(6):536–541.

test procedures used in various modes of ophthalmic practice. doi:10.1111/cxo.12073

Cornea. 2000;19(4):477-482. doi:10.1097/00003226-200007000-

00015

Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress

Publish your work in this journal

Clinical Ophthalmology is an international, peer-reviewed journal cover Central and CAS, and is the official journal of The Society of

ing all subspecialties within ophthalmology. Key topics include: Clinical Ophthalmology (SCO). The manuscript management system

Optometry; Visual science; Pharmacology and drug therapy in eye dis is completely online and includes a very quick and fair peer-review

eases; Basic Sciences; Primary and Secondary eye care; Patient Safety system, which is all easy to use. Visit http://www.dovepress.com/

and Quality of Care Improvements. This journal is indexed on PubMed testimonials.php to read real quotes from published authors.

Submit your manuscript here: https://www.dovepress.com/clinical-ophthalmology-journal

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Clinical Ophthalmology 2021:15 173

DovePress

You might also like

- Stapleton 2017Document32 pagesStapleton 2017Anggia BungaNo ratings yet

- Treatment Satisfaction Among Patients Using Anti-In Ammatory Topical Medications For Dry Eye DiseaseDocument9 pagesTreatment Satisfaction Among Patients Using Anti-In Ammatory Topical Medications For Dry Eye DiseaseAndrés QueupumilNo ratings yet

- Antibióticos y EndodonciaDocument8 pagesAntibióticos y EndodonciaPaola AndreaNo ratings yet

- Opth 9 1719Document12 pagesOpth 9 1719Anggia BungaNo ratings yet

- DM de 4Document8 pagesDM de 4Peer TutorNo ratings yet

- Current Management and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: ReviewDocument5 pagesCurrent Management and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: ReviewtriNo ratings yet

- Treatment Outcomes in The DRy Eye Amniotic MembraneDocument5 pagesTreatment Outcomes in The DRy Eye Amniotic MembraneDiny SuprianaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Advances in Dry Eye Disease TreatmentDocument25 pagesHHS Public Access: Advances in Dry Eye Disease TreatmentjojdoNo ratings yet

- Admin,+044+ +998+ +Anthea+Casey+ +galleyDocument5 pagesAdmin,+044+ +998+ +Anthea+Casey+ +galleysavitageraNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated With Symptomatic Dry Eye in Nurses in Palestine During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument7 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors Associated With Symptomatic Dry Eye in Nurses in Palestine During The COVID-19 Pandemicاحمد العايديNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Dry Eye Disease Treatment On Patient Satisfaction and QualityDocument11 pagesThe Impact of Dry Eye Disease Treatment On Patient Satisfaction and QualityribkaNo ratings yet

- Kjo 28 197Document10 pagesKjo 28 197Bassam Al-HimiariNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma 9Document13 pagesGlaucoma 9Sheila Kussler TalgattiNo ratings yet

- The Ocular Surface: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesThe Ocular Surface: SciencedirectMakmur SejatiNo ratings yet

- Dry Eye Disease: Consideration For Women's HealthDocument13 pagesDry Eye Disease: Consideration For Women's HealthIntan N HNo ratings yet

- False Myths Versus Medical Facts: Ten Common Misconceptions Related To Dry Eye DiseaseDocument10 pagesFalse Myths Versus Medical Facts: Ten Common Misconceptions Related To Dry Eye DiseaseEduardo PiresNo ratings yet

- Wong ICODiabetic Eye Care Guidelines Ophthalmology 2018Document16 pagesWong ICODiabetic Eye Care Guidelines Ophthalmology 2018Nakamura AsukaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document5 pagesJurnal 2Asniar RNo ratings yet

- The Toyos Dry Eye Diet: What to eat to heal your Dry Eye DiseaseFrom EverandThe Toyos Dry Eye Diet: What to eat to heal your Dry Eye DiseaseNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutics 14 00134Document21 pagesPharmaceutics 14 00134Aldialam RudiNo ratings yet

- The Ocular Surface: SciencedirectDocument11 pagesThe Ocular Surface: SciencedirectHenry LaksmanaNo ratings yet

- Sum - Clinical DR and DMEDocument2 pagesSum - Clinical DR and DMEsolihaNo ratings yet

- Considerations and Concepts of Case Selection in The Mangement of Post Treatment Endo. DiseaseDocument25 pagesConsiderations and Concepts of Case Selection in The Mangement of Post Treatment Endo. DiseaseWatinee WanichwetinNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Eye DiseaseFrom EverandThyroid Eye DiseaseRaymond S. DouglasNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Pain: Diagnosis, Causes, Prevention and TreatmentFrom EverandEndodontic Pain: Diagnosis, Causes, Prevention and TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Endofta CandidaDocument5 pagesEndofta CandidamorelaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing The Severity of Dry Eye: A Clear and Practical AlgorithmDocument11 pagesDiagnosing The Severity of Dry Eye: A Clear and Practical AlgorithmAsyiqin RamdanNo ratings yet

- A 4-Week, Randomized, Double-Masked Study To Evaluate Efficacy of Deproteinized Calf Blood Extract Eye Drops Versus Sodium Hyaluronate 0.3% Eye Drops in Dry Eye Patients With Ocular PainDocument9 pagesA 4-Week, Randomized, Double-Masked Study To Evaluate Efficacy of Deproteinized Calf Blood Extract Eye Drops Versus Sodium Hyaluronate 0.3% Eye Drops in Dry Eye Patients With Ocular PainnevaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal MtaDocument7 pagesJurnal MtaRizka utariNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Prevalence and Risk Factors of Dry Eye Disease Among Study GroupDocument4 pagesAssessment of Prevalence and Risk Factors of Dry Eye Disease Among Study GroupjellyNo ratings yet

- Intervention For Myopia in ChildrenDocument5 pagesIntervention For Myopia in Childrennana khrisnaNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Visual Display Terminal UsDocument19 pagesThe Association Between Visual Display Terminal Usheni ariniNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Management of Symptomatic Dry Eye Related To Lasik For Myopia, With Topical Cyclosporine ADocument8 pagesIncidence and Management of Symptomatic Dry Eye Related To Lasik For Myopia, With Topical Cyclosporine Aamirah sinumNo ratings yet

- Opth 8 581 OsmolaridadDocument10 pagesOpth 8 581 Osmolaridadmono1144No ratings yet

- Upper Eyelid Blepharoplasty Improved The Overall Periorbital Aesthetics Ratio by Enhancing Harmony Between The Eyes and EyebrowsDocument10 pagesUpper Eyelid Blepharoplasty Improved The Overall Periorbital Aesthetics Ratio by Enhancing Harmony Between The Eyes and Eyebrowstephy1394No ratings yet

- Optimizing Glaucoma Care A Holistic ApproachDocument2 pagesOptimizing Glaucoma Care A Holistic ApproachIca Melinda PratiwiNo ratings yet

- New Approaches For Diagnosis of Dry Eye DiseaseDocument11 pagesNew Approaches For Diagnosis of Dry Eye DiseaseElison J PanggaloNo ratings yet

- Ijcp 14665Document15 pagesIjcp 14665郑子豪No ratings yet

- The Columbia Guide to Basic Elements of Eye Care: A Manual for Healthcare ProfessionalsFrom EverandThe Columbia Guide to Basic Elements of Eye Care: A Manual for Healthcare ProfessionalsDaniel S. CasperNo ratings yet

- Radiation Retinopathy Detection and Management StrategiesDocument14 pagesRadiation Retinopathy Detection and Management StrategiesayminayilikNo ratings yet

- OA Recommendations For The Non-Pharmacological Core Management of Hip and Knee OsteoarthritisDocument11 pagesOA Recommendations For The Non-Pharmacological Core Management of Hip and Knee OsteoarthritisaugustinafinnaNo ratings yet

- Choroidal NeovascularizationFrom EverandChoroidal NeovascularizationJay ChhablaniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Baru 2Document6 pagesJurnal Baru 2FIRDA RIDHAYANINo ratings yet

- Public Health and Epidemiology: Aurthor (S)Document6 pagesPublic Health and Epidemiology: Aurthor (S)Sucheta MitraNo ratings yet

- 67 1427640213 PDFDocument5 pages67 1427640213 PDFIene Dhiitta PramudNo ratings yet

- Results of Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant (Ozurdex) in Diabetic Macular Edema Patients: Early Versus Late SwitchDocument11 pagesResults of Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant (Ozurdex) in Diabetic Macular Edema Patients: Early Versus Late SwitchPutri kartiniNo ratings yet

- Awareness and Knowledge Towards Common Eye Diseases of Citizens in Medina City, Saudi ArabiaDocument7 pagesAwareness and Knowledge Towards Common Eye Diseases of Citizens in Medina City, Saudi ArabiaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Eyes On Eyecare - 2021 - Dry Eye ReportDocument28 pagesEyes On Eyecare - 2021 - Dry Eye ReportEsther AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in TheDocument15 pagesDexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in TheMadalena AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Pone 0270268Document23 pagesPone 0270268Raisa BahafdullahNo ratings yet

- J Clinic Periodontology - 2023 - Herrera - Association Between Periodontal Diseases and Cardiovascular Diseases DiabetesDocument23 pagesJ Clinic Periodontology - 2023 - Herrera - Association Between Periodontal Diseases and Cardiovascular Diseases DiabetesPablo González CalviñoNo ratings yet

- Types of Sedation Used in Pediatric DentistryDocument5 pagesTypes of Sedation Used in Pediatric DentistryIna VetrilaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in OphthalmologyDocument9 pagesArtificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in OphthalmologySilvia Rossa MuisNo ratings yet

- A Survey of Dry Eye Symptoms inDocument5 pagesA Survey of Dry Eye Symptoms inJaTi NurwigatiNo ratings yet

- Whole Face Approach With Hyaluronic Acid FillersDocument11 pagesWhole Face Approach With Hyaluronic Acid Fillersalh basharNo ratings yet

- Opth 16 1641Document12 pagesOpth 16 1641Sergi BlancafortNo ratings yet

- Retrospective Study of The Pattern of Eye Disorders Among Patients in Delta State University Teaching Hospital, OgharaDocument6 pagesRetrospective Study of The Pattern of Eye Disorders Among Patients in Delta State University Teaching Hospital, OgharaHello PtaiNo ratings yet

- Asymmetric Diabetic Retinopathy.18Document9 pagesAsymmetric Diabetic Retinopathy.18Syeda F AmbreenNo ratings yet

- Delayed Inflammatory Reactions To Hyaluronic Acid 2020Document8 pagesDelayed Inflammatory Reactions To Hyaluronic Acid 2020maat1No ratings yet

- SATB All Glory Laud and HonorDocument1 pageSATB All Glory Laud and HonorGeorge Orillo BaclayNo ratings yet

- Retaining Talent: Replacing Misconceptions With Evidence-Based StrategiesDocument18 pagesRetaining Talent: Replacing Misconceptions With Evidence-Based StrategiesShams Ul HayatNo ratings yet

- Background Essay LSA Skills (Speaking)Document12 pagesBackground Essay LSA Skills (Speaking)Zeynep BeydeşNo ratings yet

- Filters SlideDocument17 pagesFilters SlideEmmanuel OkoroNo ratings yet

- Veep 4x10 - Election Night PDFDocument54 pagesVeep 4x10 - Election Night PDFagxz0% (1)

- Credit Transactions Case Digestpdf PDFDocument241 pagesCredit Transactions Case Digestpdf PDFLexa L. DotyalNo ratings yet

- Maintenance ManagerDocument4 pagesMaintenance Managerapi-121382389No ratings yet

- Hindu Dharma Parichayam - Swami Parameswarananda SaraswatiDocument376 pagesHindu Dharma Parichayam - Swami Parameswarananda SaraswatiSudarsana Kumar VadasserikkaraNo ratings yet

- Cranial Deformity in The Pueblo AreaDocument3 pagesCranial Deformity in The Pueblo AreaSlavica JovanovicNo ratings yet

- Coursera Qs-Ans For Financial AidDocument2 pagesCoursera Qs-Ans For Financial AidMarno03No ratings yet

- NyirabahireS Chapter5 PDFDocument7 pagesNyirabahireS Chapter5 PDFAndrew AsimNo ratings yet

- SDS SheetDocument8 pagesSDS SheetΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣΠΑΝΑΓΟΣNo ratings yet

- DragonflyDocument65 pagesDragonflyDavidNo ratings yet

- Derivative Analysis HW1Document3 pagesDerivative Analysis HW1RahulSatijaNo ratings yet

- AVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDocument16 pagesAVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDejan MitreaNo ratings yet

- Current Technique in The Audiologic Evaluation of Infants: Todd B. Sauter, M.A., CCC-ADocument35 pagesCurrent Technique in The Audiologic Evaluation of Infants: Todd B. Sauter, M.A., CCC-AGoesti YudistiraNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument5 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Final Exam1-Afternoon SessionDocument40 pagesFinal Exam1-Afternoon SessionJoshua Wright0% (1)

- Joshua MooreDocument2 pagesJoshua Mooreapi-302837592No ratings yet

- Bca NotesDocument3 pagesBca NotesYogesh Gupta50% (2)

- Architectural Design I: SyllabusDocument3 pagesArchitectural Design I: SyllabusSrilakshmi PriyaNo ratings yet

- Beed 3a-Group 2 ResearchDocument65 pagesBeed 3a-Group 2 ResearchRose GilaNo ratings yet

- Compilation 2Document28 pagesCompilation 2Smit KhambholjaNo ratings yet

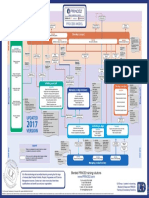

- p2 Process Model 2017Document1 pagep2 Process Model 2017Miguel Fernandes0% (1)

- Redemption and The Relief Work RevisedDocument234 pagesRedemption and The Relief Work RevisedYewo Humphrey MhangoNo ratings yet

- Per User Guide and Logbook2Document76 pagesPer User Guide and Logbook2Anthony LawNo ratings yet

- Brand Management Assignment (Project)Document9 pagesBrand Management Assignment (Project)Haider AliNo ratings yet

- Simonkucher Case Interview Prep 2015Document23 pagesSimonkucher Case Interview Prep 2015Jorge Torrente100% (1)

- Calderon de La Barca - Life Is A DreamDocument121 pagesCalderon de La Barca - Life Is A DreamAlexandra PopoviciNo ratings yet

- Selvanathan-7e 17Document92 pagesSelvanathan-7e 17Linh ChiNo ratings yet