Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The in-school marketing controversy: Balancing corporate funding needs with concerns over commercialization

Uploaded by

Jane DDOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The in-school marketing controversy: Balancing corporate funding needs with concerns over commercialization

Uploaded by

Jane DDCopyright:

Available Formats

The in-school marketing

controversy: Reaching

the teenage segment

Kathryn T. Cort

Assistant Professor of Marketing, Elon University,

Elon, North Carolina (kcort@elon.edu)

Judith H. Pairan

M ore and more, corporations are seeing high

schools as the optimum venue for selling

their goods and services to the growing,

affluent teenage market—a market currently estimated at

$150 billion-plus. After all, during three-fourths of the

Adjunct Faculty, Chapman University, Sacramento, year most teens spend a good part of their day in this

California (educator@cwo.com) controlled environment before scattering throughout the

city or countryside. Even with a wide variety of teen

media and gathering places available, none reach this crit-

John K. Ryans, Jr. ical purchasing segment as completely as do the public

James R. Good Professor of Global Strategy, Bowling and private schools.

Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio Not surprisingly, then, many marketers are constantly

(jryans@cba.bgsu.edu) looking for ways to reach teenagers during the school day.

They are often greeted by schools and educational systems

enthusiastic about the opportunities to bring in outside

funding, and even about the nature of some of the pro-

motions themselves. Whether it is an agreement with a

Consumer marketers are cola company for exclusive beverage rights or a Pizza Hut

program that rewards students for reading books, the

continually attracted to the funds provided by these companies augment an often tat-

tered budget. For many schools, in fact, they permit

large, affluent teenage market. extracurricular activities that otherwise would have to be

curtailed or drastically downsized. For others, the funds

But teens tend to be highly mobile provide much-needed new computers and other high-tech

and difficult to reach through regular equipment.

media. This makes in-school promotions Such a marketing “invasion” of the secondary schools has

especially attractive to companies. Yet come in the face of some strong opposition. As Coca-

Cola, Nabisco, Nike, and so on have increasingly turned

marketing to teens in high school is frowned

their attention to the teen market and in-school promo-

upon by many, even though such promotions tions, notes Farber (1999), a wave of critics has emerged

may offer badly needed funds and equipment to to attack the “commercialization of our nation’s class-

schools. Examining both sides of the in-school rooms.” These critics come from two or three different

camps, ranging from those who feel the schools should

marketing controversy, this article presents the

be an oasis from commercial pressures on teens to those

results of survey research conducted among who believe that corporations want to control the

school superintendents who offer their views on schools, the curricula, and students’ minds.

the topic, and discusses the need for a marketing Of course, some school administrators and secondary

code of conduct to address critics’ concerns. educators see in-school marketing as an intrusion into an

already full schedule, or doubt that the benefits from the

Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (81-85) 81

K.T. Cort et al. / The in-school marketing controversy: Reaching the teenage segment

added funds supplied by marketers can outweigh the neg- in school, at home, or elsewhere. It should not be surpris-

atives. This has led some schools, school districts, county ing, therefore, that Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and other beverage

systems, cities, and states to refuse to accept in-school companies find it highly advantageous to obtain an exclu-

marketing, or even ban it altogether. sive agreement for the sale of their goods in a school sys-

tem. Not only does this bring in immediate sales, it also

provides an opportunity to build long-term brand loyalty.

In effect, the brand becomes “the only game in town”

Beverage agreements represent during the school day. And the companies can reach

agreements with the local school or school system on the

only the tip of the in-school number of beverage machines and their locations, as well

as the use of signs on the school property, which may

marketing iceberg. Like colleges, include anything from sponsoring an athletic field score-

board to posting signboards on buses. The schools, of

many high schools have food course, benefit from such arrangements, receiving not

only funds from the sale of the exclusive agreements but

courts that bring “fast fooders” also a share in the beverage sale proceeds.

on the run to vie for outlets. And Beverage agreements represent only the tip of the in-school

marketing iceberg. For example, many high schools, like

immediate product sales are only colleges, have food courts that bring “fast fooders” on the

run to vie for outlets. And immediate product sales are

one dimension of the marketing only one dimension of their marketing activities there.

activities that involve schools. Pizza Hut has had a long-running program that rewards

students with pizza coupons for meeting certain book

reading goals. ZapMe! offers schools free high-speed com-

puters and a network of educational websites—sites that

Here we will take a closer look at various sides of the in- carry advertising targeted toward students—in return for

school marketing issue and attempt to sort out a few of the required use of its computers four hours a day. Many

the ambiguities that exist. Moreover, we will present the other leading companies have school-related promotions,

views of a three-state sample of county school superin- including Nike, Nabisco, Wal-Mart, Domino’s, Apple, and

tendents, who have the final say in many in-school mar- Hershey. In fact, Farber indicates that Cover Concepts Mar-

keting decisions and are well aware of educator, parental, keting Services has given free textbook covers featuring

and public views on the subject. Nike, Calvin Klein, and the Quaker Oats Company to stu-

dents in 31,000 schools.

Perhaps the best known and most controversial in-school

Marketers/marketing marketing program is offered by Channel One. According

to its website, Channel One is an in-school television net-

practices work that broadcasts a 12-minute daily program with two

minutes of commercials. Shown in an estimated 12,000

I

n-school marketing is not a twenty-first century phe-

nomenon. Many of us can recall from years ago local

companies advertising in our high school yearbooks,

automobile companies such as Ford providing the cars for The beverage contract

driver’s training, and beverage-sponsored football score-

boards. But although the companies undoubtedly hoped On September 23, 2002, the Stow-Monroe Falls School

District in Ohio entered into an exclusive 10-year bever-

to receive some benefit from such advertising—perhaps a

age contract with Akron Coca-Cola Company for an esti-

favorable attitude toward the brand or the business— mated $750,000. The agreement specified the number of

rarely did they have a carefully crafted marketing strategy vending machines, their locations, and the array of bever-

designed to achieve immediate sales objectives or longer- ages to be provided. For exclusive promo-

term brand awareness goals. tional rights and beverage availability rights,

Coca-Cola was to pay the school district

An excellent illustration of the former is the “Cola Wars”

$350,000 over the next ten years. The school

fought to win exclusive beverage rights in individual would also get a percentage of the sales, as

schools or school systems. (An example of Coca-Cola’s well as a new scoreboard for its stadium.

agreement with the Stow, Ohio school system is presented

in the sidebar.) US teenagers consume enormous amounts Source: Schuck (2002)

of soft drinks, fruit juices, and bottled water daily, whether

82 Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (81-85)

K.T. Cort et al. / The in-school marketing controversy: Reaching the teenage segment

schools nationwide, the program carries a wide range of 18 percent were negative about the effect of marketing in

news and student interest shows. In return for permitting schools, whereas one-third were positive. Further, more

Channel One to operate in the school and letting the pro- than half of the principals indicated that exclusive vendor

gram be shown during class, the school gets TV sets and agreements were beneficial to extracurricular programs.

television receiving equipment. Naturally, educators vary

If one were to generalize, it appears that the view of a

in their reaction to the overall quality of Channel One

large portion of educators and parents tends to favor in-

programming; some find it very useful in terms of current

school marketing, as long as it remains at its current level.

events and teen-related programs, while others do not.

What they seem to see is a trade-off between a little com-

However, it is clearly original and designed specifically for

mercialization and some badly needed funding. A clearer

its teenage target audience.

From a marketing perspective, then, it is clear that a wide

range of US consumer goods corporations see high schools

as excellent locations to develop brand awareness, to dif-

ferentiate themselves from competitors, and even to build

The view of a large portion of

a long-term customer base. Thus, they will continue to try educators and parents seems to

to find creative ways to enter the classroom realm.

favor in-school marketing, as

long as it remains at its current

The opinions

level. What they likely see is a

A

s noted at the outset, many educators, education

groups, consumer activists (individuals and

groups), legislators, and parents and parent

trade-off between a little

groups actively oppose advertising in the schools. While commercialization and some

they are more adamantly against it in the lower grades

and middle schools, they are also strongly opposed to any badly needed funding.

advertising at the high school level. Henry Giroux (1999),

one of the more outspoken of these critics, states that

“schools have condoned a transformation to commercial

spheres.…Their students become subjects to the whims picture of educational attitudes toward in-school market-

and practices of marketers.” Alex Molnar (1996) notes ing is provided by the results of our three-state survey of

that the “exploitation of our schools by corporate huck- county superintendents.

sters willing to put their short-term profit ahead of the

Superintendents’ views

public’s long-term well-being makes the already difficult

task of school improvement harder.” A third nationally During 2002, we surveyed a sample of county superin-

recognized critic, Alfie Kohn (2002), speaking specifically tendents from Oregon, Iowa, and North Carolina. The

of Channel One, maintains that rationale for selecting three widely separated and diverg-

ing states was to obtain broader (and more representa-

the advertisers seem to be getting their money’s

tive) results. Some of the findings were as follows:

worth; researchers have found that Channel One

viewers, as contrasted with a comparable group of 1. Most believe that by careful screening of corporate in-

students, not only thought more highly of the school messages/programs, schools can reap the bene-

products advertised on the program but were more fits of added funds without exploiting students.

likely to agree with statements such as “A nice car is

2. Most believe that selling the “naming rights” for

more important than schools” and “I want what I

libraries, auditoriums, and other physical facilities to

see advertised.”

corporate sponsors is inappropriate and cheapens pub-

Despite such strident comments, much of the education lic education.

community sees in-school marketing as positive. Their

3. Roughly two-thirds believe it is difficult to keep up with

views tend to range from those who feel that high school

computer technology without corporate marketing or

students in particular have been accustomed to judging

similar external funds.

commercials virtually from birth and are able to distin-

guish them from the news, to others who believe the ben- 4. Most believe that parents are not opposed to corporate

efits of the external funding far outweigh any negatives. advertising at the secondary school level, but are op-

In fact, an extensive study by Feuerstein (2001) of high posed to it at the elementary level.

school principals in Pennsylvania found that only about

Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (81-85) 83

K.T. Cort et al. / The in-school marketing controversy: Reaching the teenage segment

5. Marketers should be aware of a growing backlash to in- divided on the issue. However, marketers should be cau-

school marketing. tioned on two of the findings. First, roughly two-thirds of

the superintendents in each state believe that corporate

One surprise from the survey was the similarity in views

marketing research does not have important educational

among the superintendents across the three states. Consid-

value to students and should not be conducted in schools.

ering the geographic distances and different economies

Second, most believe there is a growing backlash against

and local cultures, we had expected much more variation

in-school marketing. This may be taken as a warning of

on the issues. Table 1 indicates that the only real disagree-

some resentment for having to depend heavily on market-

ment occurred over whether external funds were needed

ing resources to support ongoing programs. Moreover,

to keep up with technological advances. The North Car-

both of these responses suggest that companies should be

olina and Iowa county superintendents felt that such funds

careful in their promotions and must not try to exploit the

were needed, while the Oregon respondents were equally

current base of support for marketing in high schools.

Table 1

Superintendents’ views on several “in-school marketing” issues

Issue

1. Corporate marketing arrangements

State

N. Carolina

Agree (%)

88.0

Disagree (%)

12.0

D espite the growing number

of vocal critics, marketers

should expect to find con-

tinued opportunities to use certain

types of in-school marketing, at least

often provide public schools with badly Iowa 90.0 10.0 in the near term. This is especially

needed sources. Oregon 87.5 12.5 true given the limited tax funds avail-

Average 88.5 11.5 able to provide for the total academic

2. Schools need external funds to help N. Carolina 77.0 23.0 and extracurricular needs of second-

keep up with new technology for the Iowa 68.0 32.0 ary schools today. In particular, it is

classroom. Oregon 50.0 50.0 the extracurricular activities—every-

Average 65.0 35.0 thing from athletics to bands to

school plays—that have especially

3. Most parents are opposed to in-school N. Carolina 28.0 72.0

marketing at the high school level. Iowa 23.0 77.0 suffered, as school levy issues have

Oregon 25.0 75.0 mounted in recent years.

Average 25.3 74.7 Given the overall climate, however, it

4. Corporate naming rights for high N. Carolina 40.0 60.0 might be wise for the companies tar-

schools would not necessarily com- Iowa 36.0 64.0 geting teens to begin to build the sort

promise the schools’ academic integrity. Oregon 42.0 58.0 of goodwill that could maintain in-

Average 39.3 60.7 school marketing beyond periods of

5. School administrators are more apt N. Carolina 91.0 9.0 budget emergencies. Most high

to allow in-school marketing programs Iowa 93.0 7.0 school constituencies seem to have

in grades 9–12 than for lower grades. Oregon 96.0 4.0 accepted the exclusive beverage con-

Average 93.3 6.7 tracts and sports-related program-

6. School administrators should permit N. Carolina 35.0 65.0 ming. The major criticisms are di-

marketing research to be conducted in Iowa 28.0 72.0 rected toward companies that are

class to acquaint students with the process Oregon 29.0 71.0 providing book jackets and academic

(i.e., provide an educational experience). Average 30.7 69.3 content-related contests and promo-

tions. Farber describes one school

7. Marketers should be aware of a growing N. Carolina 88.0 12.0 that was forced to change textbooks

backlash against in-school marketing. Iowa 73.0 27.0 because the books were found to

Oregon 87.0 13.0

contain many product-specific exam-

Average 82.7 17.3

—————————

ples and illustrations. Moreover, mar-

keters should take note of critics’

Research note: During January–May 2002, the authors conducted a highly struc-

charges that companies want to alter

tured mail survey of a random sample of 100 county superintendents in each of

three states (North Carolina, Iowa, and Oregon). Responses were received from high school curricula to fit their own

123 participants (North Carolina 43, Iowa 55, and Oregon 23) for an overall 41 needs.

percent response rate. All the data are presented here by individual state, due to

the response rate differences. The Stapel Technique, a forced-choice instrument, To counter such charges, marketing

was employed for the survey; the scale ranged from –3 to –1 on the negative and advertising associations should

scale and 1 to 3 on the positive scale. perhaps voluntarily establish a code of

conduct for in-school marketing. With

84 Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (81-85)

K.T. Cort et al. / The in-school marketing controversy: Reaching the teenage segment

a number of groups seeking state and federal legislation Finally, the development of such a code would be espe-

to ban this activity, such a code could be a very appropri- cially valuable to the many school administrators who

ate response for businesses to take. It could establish have long been proponents of in-school marketing. It

parameters for everything from Channel One-like adver- would signal to critics that the corporate world’s objec-

tising to Pizza Hut contests to book jackets. In that way, tives are not inconsistent with the secondary education

marketers would indicate to school officials and oppo- community. ❍

nent groups alike that their concerns are recognized (and

shared) and that their in-school marketing practices

would be consistent with student and school interests and References and selected bibliography

needs. For example, by agreeing to limit marketing to stu-

Brand, Jeffrey E., and Bradley S. Greenberg. 1994. Commercials

dents in grades 9–12, companies would be responding to

in the classroom: The impact of Channel One advertising.

the school administrators’ concerns noted in Number 5 in Journal of Advertising Research 34/1 (January-February): 18-27.

Table 1. Farber, Peggy. 1999. Schools for sale. Advertising Age (25 Octo-

Similarly, corporate and advertising representatives could ber): 22ff.

meet with a sample of school administrators and county Feuerstein, Abe. 2001. Selling our schools? Principals’ views on

schoolhouse commercialism and school-business instructions.

superintendents to determine why nearly three-fourths of

Educational Administration Quarterly 37/3 (August): 322-371.

our respondents were opposed to having marketing Giroux, Henry A. 1999. Schools for sale: Public education, cor-

research conducted in schools and why there appears to porate culture, and the citizen-consumer. The Educational

be a growing backlash against in-school marketing. Such Forum 63/2 (Winter): 140-148.

efforts could result in actions to ensure that the code of Kohn, Alfie. 2002. The 500-pound gorilla. Phi Delta Kappan

conduct (or set of guidelines) would address the types or (October):113-119.

forms of advertising that are felt to be appropriate and Molnar, Alex. 1996. Giving kids the business. Boulder, CO: West-

inappropriate, as well as the degree of “hard sell” that view Press:.

seems acceptable. The code could then be voluntarily Schuck, Andrew. 2002. Contract with Coke hikes school revenue.

signed and adopted by the trade association(s) as well as Stow (Ohio) Sentry (27 October): 1.

by individual corporations.

Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (81-85) 85

You might also like

- The Open Banking StandardDocument148 pagesThe Open Banking StandardOpen Data Institute95% (21)

- Developmental AssessmentDocument15 pagesDevelopmental AssessmentShailesh MehtaNo ratings yet

- 4.1 Simple Harmonic Motion - WorksheetDocument12 pages4.1 Simple Harmonic Motion - Worksheetkoelia100% (1)

- Marketing of Educational ServicesDocument6 pagesMarketing of Educational ServicesDrisya K DineshNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Marketing Management Global Edition 15th Edition Philip Kotler Kevin Lane KellerDocument16 pagesSolution Manual For Marketing Management Global Edition 15th Edition Philip Kotler Kevin Lane Kellervennedrict7yvno100% (21)

- Cace 00 02 Exec SummaryDocument3 pagesCace 00 02 Exec SummaryNational Education Policy CenterNo ratings yet

- CommercializationDocument2 pagesCommercializationAnna Bruzon-RafalloNo ratings yet

- Branding CollegeDocument2 pagesBranding CollegePuneet BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Marketing of CollegesDocument5 pagesMarketing of CollegesairtravinstituteNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document9 pagesChapter 2karylle jhane tanguinNo ratings yet

- ReadingDocument2 pagesReadingDaisyNo ratings yet

- 2011-Marketing The Institution To Perspective Student-A ReviDocument17 pages2011-Marketing The Institution To Perspective Student-A Revisiti mafulaNo ratings yet

- School Commercialism, Student Health, and The Pressure To Do More With LessDocument41 pagesSchool Commercialism, Student Health, and The Pressure To Do More With LessNational Education Policy CenterNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument1 pageEssayGregory MarcosNo ratings yet

- The Innovative University: Changing The DNA of Higher EducationDocument7 pagesThe Innovative University: Changing The DNA of Higher Educationfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Scope of Marketing For Schools in 21st Century in IndiaBy Students at Universal Business School, MumbaiDocument6 pagesScope of Marketing For Schools in 21st Century in IndiaBy Students at Universal Business School, MumbaiInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Cace 00 02 Press ReleaseDocument3 pagesCace 00 02 Press ReleaseNational Education Policy CenterNo ratings yet

- Education As Business: Some Musings in The Context of Higher Education in GoaDocument6 pagesEducation As Business: Some Musings in The Context of Higher Education in GoaBabu GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Universities in The MarketplaceDocument7 pagesUniversities in The MarketplacejdliboroNo ratings yet

- Tsiros 2021 JRDocument18 pagesTsiros 2021 JRevlin mrgNo ratings yet

- Epsl 0409 103 CeruDocument106 pagesEpsl 0409 103 CeruNational Education Policy CenterNo ratings yet

- 2003 Spring NairDocument3 pages2003 Spring Nairjharney4709No ratings yet

- Creating Brand Value in Higher EducationDocument7 pagesCreating Brand Value in Higher EducationcrisseveroNo ratings yet

- 4 QuestionsDocument9 pages4 QuestionsAsadulla KhanNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About 4psDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About 4pswopugemep0h3100% (1)

- Commerce ProjectDocument16 pagesCommerce ProjectParth WayneNo ratings yet

- Paying For CollegeDocument12 pagesPaying For CollegeResumeBearNo ratings yet

- Online Education Startup for All StudentsDocument2 pagesOnline Education Startup for All StudentsDanNo ratings yet

- Student Advantage Captures The College Market Through An Integration of Their Off and Online BusinessesDocument17 pagesStudent Advantage Captures The College Market Through An Integration of Their Off and Online BusinessesMrx QuyetNo ratings yet

- The Ninth Annual Report On Schoolhouse Commercialism Trends: 2005-2006Document57 pagesThe Ninth Annual Report On Schoolhouse Commercialism Trends: 2005-2006National Education Policy CenterNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About College TuitionDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About College Tuitionefdkhd4e100% (1)

- Kristina Saha Capstone-PitchDeckDocument23 pagesKristina Saha Capstone-PitchDeckKristina SahaNo ratings yet

- Palos Verdes Presentation Final RevisedDocument39 pagesPalos Verdes Presentation Final RevisedLeonie HaimsonNo ratings yet

- Black Saa 7620 Issue PaperDocument7 pagesBlack Saa 7620 Issue Paperapi-255493839No ratings yet

- Opportunies and Threats AnalysisDocument7 pagesOpportunies and Threats AnalysisKisseah Claire EnclonarNo ratings yet

- Food Cart ThesisDocument5 pagesFood Cart Thesisafjrooeyv100% (2)

- Creative Ads Don't Always Increase SalesDocument5 pagesCreative Ads Don't Always Increase SalesJefaradocsNo ratings yet

- Case Study: First Class Trading Corporatio N: Team 4Document32 pagesCase Study: First Class Trading Corporatio N: Team 4Daliya Manuel0% (1)

- University of The East - Shs - Abm Caloocan Campus PageDocument5 pagesUniversity of The East - Shs - Abm Caloocan Campus PageJPIA-UE Caloocan '19-20 AcademicsNo ratings yet

- Economists Skeptical of Free Market Approach to EducationDocument2 pagesEconomists Skeptical of Free Market Approach to EducationcarminNo ratings yet

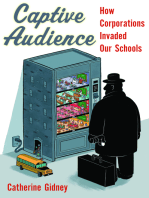

- Captive Audience: How Corporations Invaded Our SchoolsFrom EverandCaptive Audience: How Corporations Invaded Our SchoolsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- 1969kotler LevyDocument7 pages1969kotler LevyLuCyNo ratings yet

- Secondary ResearchDocument33 pagesSecondary Researchapi-524118899No ratings yet

- Higher Education Business ModelDocument11 pagesHigher Education Business ModelTogar SimatupangNo ratings yet

- Epsl 0511 103 Ceru ExecDocument6 pagesEpsl 0511 103 Ceru ExecNational Education Policy CenterNo ratings yet

- Rethinking 101 A New Agenda For University and Higher Education System LeadersDocument14 pagesRethinking 101 A New Agenda For University and Higher Education System LeadersJason PriceNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis: A Simple Strategy at Costco: Informative Background InformationDocument15 pagesCase Analysis: A Simple Strategy at Costco: Informative Background InformationFred Nazareno CerezoNo ratings yet

- Colorado State University PHD DissertationDocument10 pagesColorado State University PHD DissertationBuyLiteratureReviewPaperPaterson100% (1)

- Integrated and Communications Plan: MarketingDocument33 pagesIntegrated and Communications Plan: MarketingSherbaz MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Teaching Global Citizenship Through FashionDocument5 pagesTeaching Global Citizenship Through Fashionmarketing84comNo ratings yet

- College Tuition ThesisDocument5 pagesCollege Tuition Thesismaggiecavanaughmadison100% (2)

- International Trade LawDocument22 pagesInternational Trade LawLeonard TemboNo ratings yet

- Unhealthy-Food-Marketing-on-Commercial-Educational-_2021_American-Journal-ofDocument5 pagesUnhealthy-Food-Marketing-on-Commercial-Educational-_2021_American-Journal-ofEstreLLA ValenciaNo ratings yet

- WertyuDocument35 pagesWertyugayuh aji pNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Marketing To ChildrenDocument11 pagesEthics in Marketing To ChildrenYusuf BhanpurawalaNo ratings yet

- Systems Model for Integrated Marketing CommunicationsDocument17 pagesSystems Model for Integrated Marketing CommunicationsJessica SellersNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Contemporary Business-Wiley (2016)Document29 pagesChapter 2 Contemporary Business-Wiley (2016)Putu DenyNo ratings yet

- Is education too commercializedDocument3 pagesIs education too commercializedhussnain zaffarNo ratings yet

- ReflectionOnAdvertisingDiscussion_AdProDimDocument3 pagesReflectionOnAdvertisingDiscussion_AdProDimchild BornNo ratings yet

- Who Participates? An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Two Voucher Programs in The United StatesDocument16 pagesWho Participates? An Analysis of School Participation Decisions in Two Voucher Programs in The United StatesCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- The New Marketing RealitiesDocument15 pagesThe New Marketing RealitiesRammohanreddy RajidiNo ratings yet

- MinigasmDocument1 pageMinigasmmustafa27No ratings yet

- Grading Higher EducationDocument34 pagesGrading Higher EducationCenter for American Progress100% (1)

- Item 14Document17 pagesItem 14Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Ie1c03863 Si 001Document9 pagesIe1c03863 Si 001Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Fnins 05 00079Document15 pagesFnins 05 00079Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Association of Diarrhea With Anemia Among Children Under Age Five Living in Rural Areas of IndonesiaDocument7 pagesAssociation of Diarrhea With Anemia Among Children Under Age Five Living in Rural Areas of IndonesiaJane DDNo ratings yet

- ItsyourFuneralReport 15may17Document45 pagesItsyourFuneralReport 15may17Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Innovation Effectuation and UncertaintyDocument22 pagesInnovation Effectuation and UncertaintyJane DDNo ratings yet

- Burnett2017Document16 pagesBurnett2017Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Item 10Document14 pagesItem 10Jane DDNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0099133321000380 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0099133321000380 MainJane DDNo ratings yet

- Paper 3Document17 pagesPaper 3Jane DDNo ratings yet

- The Risk Factors For Child Anemia Are Consistent Across 3 National Surveys in NepalDocument15 pagesThe Risk Factors For Child Anemia Are Consistent Across 3 National Surveys in NepalJane DDNo ratings yet

- Art 2Document22 pagesArt 2Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Branding For The Public Sector Creating Building A... - (BRANDING FOR THE PUBLIC SECTOR)Document4 pagesBranding For The Public Sector Creating Building A... - (BRANDING FOR THE PUBLIC SECTOR)Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Paper 2Document12 pagesPaper 2Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Fine Root Dynamics Across Pantropical Rainforest eDocument24 pagesFine Root Dynamics Across Pantropical Rainforest eJane DDNo ratings yet

- Logistics Management in Practice-Towards Theories of Complex LogisticsDocument19 pagesLogistics Management in Practice-Towards Theories of Complex LogisticsLê Bảo TrânNo ratings yet

- Zaman 2021Document14 pagesZaman 2021Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Research On Agricultural ProduDocument8 pagesResearch On Agricultural ProduJane DDNo ratings yet

- 4D BIM For Construction LogistDocument25 pages4D BIM For Construction LogistJane DDNo ratings yet

- Considerations Regarding The IDocument7 pagesConsiderations Regarding The IJane DDNo ratings yet

- Rosier 2022Document9 pagesRosier 2022Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Greening The Guest Bedroom Exploring Hosts Perspectives On Environmental Certification For AirbnbDocument12 pagesGreening The Guest Bedroom Exploring Hosts Perspectives On Environmental Certification For AirbnbJane DDNo ratings yet

- Logistics and Supply Chain ManDocument26 pagesLogistics and Supply Chain ManJane DDNo ratings yet

- Logistics Management in PractiDocument18 pagesLogistics Management in PractiJane DDNo ratings yet

- 1-Perceived Transformational LeadershipDocument3 pages1-Perceived Transformational LeadershipJane DDNo ratings yet

- Reliability Analysis and LifetDocument9 pagesReliability Analysis and LifetJane DDNo ratings yet

- Destination Net-Zero: What Does The International Energy Agency Roadmap Mean For Tourism?Document19 pagesDestination Net-Zero: What Does The International Energy Agency Roadmap Mean For Tourism?Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Journal of Sustainable TourismDocument16 pagesJournal of Sustainable TourismJane DDNo ratings yet

- 10 1016j Ijhm 2020 102498Document11 pages10 1016j Ijhm 2020 102498Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Foods 11 00382 v2Document37 pagesFoods 11 00382 v2Jane DDNo ratings yet

- Ali, B.H., Al Wabel, N., Blunden, G., 2005Document8 pagesAli, B.H., Al Wabel, N., Blunden, G., 2005Herzan MarjawanNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Different Grains Used For ProductionDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Different Grains Used For ProductionAmin TaleghaniNo ratings yet

- Ms - 1294 - Part3 - 1993 - WALL AND FLOOR TILING PART 3 - CODE OF PRACTICE FOR THE DESIGN AND INSTALLATION OF CERAMIC FLOOR AND MOSAICSDocument7 pagesMs - 1294 - Part3 - 1993 - WALL AND FLOOR TILING PART 3 - CODE OF PRACTICE FOR THE DESIGN AND INSTALLATION OF CERAMIC FLOOR AND MOSAICSeirenatanNo ratings yet

- American Cows in Antarctica R. ByrdDocument28 pagesAmerican Cows in Antarctica R. ByrdBlaze CNo ratings yet

- Quantum Dot PDFDocument22 pagesQuantum Dot PDFALI ASHRAFNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4 - Animated Data VisualizationDocument35 pagesLecture 4 - Animated Data VisualizationAnurag LaddhaNo ratings yet

- Coding and Decoding Practice TestDocument13 pagesCoding and Decoding Practice TestRaja SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Ant Amb452000 1502 Datasheet PDFDocument2 pagesAnt Amb452000 1502 Datasheet PDFIwan Arinta100% (1)

- Final Research Dossier - Joey KassenoffDocument11 pagesFinal Research Dossier - Joey Kassenoffapi-438481986No ratings yet

- Robert Frost BiographyDocument3 pagesRobert Frost Biographypkali18No ratings yet

- Bringing Class to Mass: L'Oreal's Plénitude Line Struggles in the USDocument36 pagesBringing Class to Mass: L'Oreal's Plénitude Line Struggles in the USLeejat Kumar PradhanNo ratings yet

- MDD FormatDocument6 pagesMDD FormatEngineeri TadiyosNo ratings yet

- Soal Bing XiDocument9 pagesSoal Bing XiRhya GomangNo ratings yet

- 2016 Practical Theory Questions SolutionDocument36 pages2016 Practical Theory Questions Solutionsheeess gaadaNo ratings yet

- Why I Am Not A Primitivist - Jason McQuinnDocument9 pagesWhy I Am Not A Primitivist - Jason McQuinnfabio.coltroNo ratings yet

- Generator Honda EP2500CX1Document50 pagesGenerator Honda EP2500CX1Syamsul Bahry HarahapNo ratings yet

- ECN 202 Final AssignmentDocument10 pagesECN 202 Final AssignmentFarhan Eshraq JeshanNo ratings yet

- PDMS JauharManualDocument13 pagesPDMS JauharManualarifhisam100% (2)

- CHE135 - Ch1 Intro To Hazard - MII - L1.1Document26 pagesCHE135 - Ch1 Intro To Hazard - MII - L1.1SyafiyatulMunawarahNo ratings yet

- Xray Order FormDocument1 pageXray Order FormSN Malenadu CreationNo ratings yet

- February 2023Document2 pagesFebruary 2023rohitchanakya76No ratings yet

- Nursing Health History SummaryDocument1 pageNursing Health History SummaryHarvey T. Dato-onNo ratings yet

- MiscDocument23 pagesMisccp2489No ratings yet

- Makalah KesehatanDocument9 pagesMakalah KesehatanKUCLUK GamingNo ratings yet

- Cost MGMT Accounting U4Document74 pagesCost MGMT Accounting U4Kai KeatNo ratings yet

- 0000 0000 0335Document40 pages0000 0000 0335Hari SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Rizal's Extensive Travels Abroad for Education and Revolution (1882-1887Document6 pagesRizal's Extensive Travels Abroad for Education and Revolution (1882-1887Diana JeonNo ratings yet