Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bibliography: Section II

Uploaded by

Didar AkınOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bibliography: Section II

Uploaded by

Didar AkınCopyright:

Available Formats

Akın 1

Contents

1

Abstract

2

Introduction

3

Urban Conservation

4

Gentrification with and against the Local Residents

5

A Thematic Discussion on the Concepts of Conservation and

Gentrification

6

The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City: Inequality

and Crime

7

Conclusion: The Outcomes and the Consequences

Bibliography

Abstract

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 2

With particular regard for drawing a certain borderline

between urban conservation and gentrification, in the first

section, the concept of urban conservation is going to be

taken into consideration to impede a range of implicit

understandings. Parallel to the stated notion, the following

section will be spared for the concept of gentrification in a

focused scope. Intended as a comparison section of the paper,

a thematic discussion on the phenomena of urban conservation

and gentrification is going to be provided. Subsequently, the

selected case study of Brooklyn Heights, NY representing the

issues of inequality and crime discussed in the gentrification

section will be given a part before to finalize the paper by

discussing the outcomes and the consequences in the conclusion

section.

Key words: Urban Conservation. Gentrification. Brooklyn

Heights, NY, Inequality. Crime.

Urban Conservation

A historic urban city is an accumulation of

archeological layers of past and present turning into a

heritage respected as something needed to be conserved that

has been stemmed from the sense of feeling responsible for

both previous and future generations and an enduring

discernment of wonder for the past that is both more

accessible and more vulnerable than ever before according to

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 3

Lowenthal.1 2

Indeed, the very idea of conservation of urban

heritage lies at the basis of the following notion explained

by Orbasli as "the interaction of human beings with the past

and the present, with buildings, spaces and one another

produces an urban dynamism and creates a spirit of place". 3

Apart from the conceptual definition, two types of situations

defined by Chau can be taken into account that "the first is

to conserve historical buildings located in intensively

developing cities, and the second is when it is more feasible

to repurpose rather than redevelop relatively modern

functional buildings that are in good condition, such as

factories, warehouses, and schools".4 Along with, a range of

constituents like international and local regulatory

frameworks, financial arrangements, political forces,

architectural constraints, and innovative ideas influence the

effectiveness of these situations.5

1

Orbasli, Aylin. Tourists in Historic Towns Urban Conservation and

Heritage Management. London, England: E & FN Spon, 2000, 8.

2

Roca, Pere, Lourenc̦

o Paulo B., and Angelo Gaetani. Historic

Construction and Conservation: Materials, Systems and Damage. New

York, NY: Routledge, 2019, 1.

3

Orbasli, Aylin. Tourists in Historic Towns Urban Conservation and Heritage

Management. London, England: E & FN Spon, 2000, 8.

4

Chau K. W., Lennon H. T. Choy, and Ho Yin Lee. “Institutional arrangements

for urban conservation.” J Hous and the Built Environ (2018) 33:455–463

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9609-2,456.

5

Chau K. W., Lennon H. T. Choy, and Ho Yin Lee. “Institutional arrangements

for urban conservation.” J Hous and the Built Environ (2018) 33:455–463

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9609-2,457.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 4

Gentrification with and against the Local Residents

The concept of gentrification, first coined by the British

sociologist Ruth Glass, can be defined as the ostensible

process of “changing a working-class or vacant area into

middle-class residential or commercial use”, which has

economic, cultural, political, social, and institutional

repercussions.6 Had ideological and theoretical value, the

concept of gentrification may have been stemmed from the

notion of ameliorating the existing condition of the subjected

area by offering urban regeneration and alleviating the socio-

economic status of the local residents; yet, the indispensable

ramifications like social exclusion and polarization are

likely to occur because the racial, ethnic, class, gender and

sexual identities generating demographic characteristics of

local residents and gentrifiers diverge.

A Thematic Discussion on the Concepts of Conservation and

Gentrification

It may seem both concepts have been driven by the idea of

giving human being the central place by either protecting the

valued historic heritage or alleviating the existing condition

in an urban extent; nonetheless, as it is delineated in the

previous sections that gentrification managed in the global

market serves to capitals and has resulted in antagonistic

6

Lees, Loretta, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wyly. Gentrification. New York, USA:

Routledge, 2008, 3.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 5

outcomes, which make the concept quite removed from the notion

of being respectful, responsible and prudent. In order to

enhance the clarity, to provide a more extended comparison

between the concepts would be beneficial, since both are quite

complex phenomena differing in reasons, processes, and

outcomes. In the interest of examining the reasons driving the

occurrence of these phenomena, the aspects of conservation and

gentrification are needed to be examined within the light of

the answer to the question of for whom they have proceeded.

Authenticity and integrity appear as the most important

aspects of conservation, concomitantly a value-based approach

is given a crucial place beside the concepts of 'assortment in

cultural identities' and 'sense of place'. On the other hand,

gentrification which is a sort of alteration in an urban scale

that as a displacement of so-called 'hackneyed' buildings

occupied by low-income households with the luxurious ones

offering an improved neighborhood. When the approach in the

conservation process is declared in Burra Charter as "changing

as much as necessary but as little as possible", in

gentrification a measureless changing procedure, on which

embellishment has based, is the case. Moreover, it must be no

harm to state that in this embellishment based changing

'values', 'assortment in cultural identities' and 'the sense

of place' are disregarded since rather than to respect and to

protect, the observed actions in gentrification are to despise

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 6

and to dispel.7 In this concern, the question ‘for whom ?’ can

be given an answer as for the past, present, and future

generations when the concept of conservation is taken into

consideration, for the wealthier is the answer for

gentrification. To move on with the comparison of the

processes, to have a comprehensive understanding about how

sophisticated conservation process is, The Burra Charter can

be taken into account as the reference in which the steps of

the process are categorized under seven subtitles which are in

respect to order i) "to understand the place", ii) "to assess

cultural significance", iii)"to identify all factors and

issues", iv)" to develop policy", v) "to prepare a management

plan", vi) "to implement the management plan" and vii) "to

monitor the results and to review the plan". 8 Conversely, the

process of gentrification is managed by capitals having an

economic-based policy by disregarding the significance of the

place, and the present and future condition of the local

residents. Ultimately, before to finalize the section, the

outcomes of conservation and gentrification can be mentioned

in a general context since both concepts have a quite complex

process varying in results one case to another. Resulted from

a range of different influences, the outcome of a long

7

“Burra Charter-The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural

Significance.” Australia ICOMOS Incorporated International Council on

Monuments and Sites, 2013, 3.

8

“Burra Charter-The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural

Significance.” Australia ICOMOS Incorporated International Council on

Monuments and Sites, 2013, 10.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 7

development of conservation is stated as the consciousness of

the significance of the common heritage.9 On the contrary,

"moved into very different urban contexts like rapidly

urbanizing, post-colonial, post-communist, or

communo/capitalist that all overlaid by a diversity of

cultural and religious forms"; gentrification, in this regard,

has various outcomes having social, cultural, economic,

political dimensions besides substantial physical

alterations.10 Hence, in consideration of discussing

gentrification's relation to the concept of urban

conservation, and the outcomes of it in a more focused scope,

the selected case study is to be reckoned under the subsequent

heading.

The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City:

Inequality and Crime

To start with the gentrification in the case of Brooklyn

Heights and its relation to urban conservation, there must be

no harm to state that the examples of the traditional or

classic form renewed by individual gentrifiers through

extravagant interior renovation and adding of new paving,

9

Jokilehto, Jukka. “A History of Architectural Conservation.” Oxford, UK:

Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999,301.

10

Atkinson, Rowland, and Gary Bridge, eds. Gentrification in a Global

Context: The New Urban Colonialism. Firsted. New York, USA: Routledge,

2005, 12.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 8

ramps, lighting, recreational areas, and gardens are likely to

be observed in the case of Brooklyn Heights.11

Figure.1. A four-bedroom,

five and a half bathroom,

two family rowhouse, built

in 1899 on 0.05 acres,

listed for $4.35 million.

R

12

etrived from “Fort Greene, Brooklyn: Riding the Wave of Gentrification.”

While the competition for land uses and concomitantly

preservation of the common good are concerned by urban

conservation; in addition to conserving historic heritage and

repurposing it; a completely reverse approach is likely to be

perceived in the Brooklyn Heights case since the main concern

is to serve to the richest rather than to preserve, although

11

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. The Gentrification Debates: a Reader. London:

Taylor and Francis, 2013, 48.

12

Lasky, Julie. “Fort Greene, Brooklyn: Riding the Wave of Gentrification.”

The New York Times. New York USA: November 6, 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/realestate/fort-greene-brooklyn-riding-

the-wave-of-gentrification.html.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 9

historic buildings are kept in a good situation as part of

subject gentrification.13

Figure.2. Income Change in Brooklyn Heights, 1970-2000.Retrived from

Gentrification by Loretta Lees and Tom Slater.14

To emphasize the situation of intensified gentrification,

named by Lees with a new conceptual phenomenon, super

gentrification, the case of Brooklyn Heights can be regarded

as a model of "intense investment and conspicuous

consumption".15 Not only a higher level of gentrification but

also superimposed on an already gentrified neighborhood is

indicated with the term.16 Supplementarily, “a dramatic increase

in income and the progressive displacement of lower-income

families by higher-income families” have been demonstrated in

13

Chau K. W., Lennon H. T. Choy, and Ho Yin Lee. “Institutional

arrangements for urban conservation.” J Hous and the Built Environ (2018)

33:455–463 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9609-2,456.

14

Lees, Loretta, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wyly. Gentrification. New York, USA:

Routledge, 2008,152.

15

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. The Gentrification Debates: a Reader. London:

Taylor and Francis, 2013, 31.

16

Lees, Loretta, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wyly. Gentrification. New York, USA:

Routledge, 2008,152.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 10

census data from 1970 to 2000 provided in Lees's analysis (See

Figure 1.).17 Class segregation perpetuating the system of

social stratification has been created by gentrifiers, which

consequently has been creating social inequality according to

DeSena.18 In this connection, the status of a substantial income

difference between gentrifiers and local residents, which has

been given birth by the waves of densified gentrification,

demonstrates an indisputable inequality in the socio-economic

condition that has a penchant to lead an increment in the

crime rate of the region. As an attempt for being more

expository, to provide the relevant section from the article

entitled “Gentrification and Violent Crime in New York City”

seems like a plausible step that "gentrification should be

positively associated with crime as the process introduced

young, middle-class professionals into disadvantaged

neighborhoods populated by impoverished residents who were

often resentful that gentrification was occurring in their

neighborhood".19

Bibliography

17

Lees, Loretta, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wyly. Gentrification. New York, USA:

Routledge, 2008,154.

18

DeSena, N., Judith. Gentrification and Inequality in Brooklyn: The New

Kids on the Block. New York, USA: Lexington Books, 2009,57.

19

Barton S. Michael. “Gentrification and Violent Crime in New York City.”

Crime & Delinquency 2016, Vol. 62(9) 1180 –1202.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128714549652,5.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 11

Atkinson, Rowland, and Gary Bridge, eds. Gentrification in a Global

Context: The New Urban Colonialism. Firsted. New York, USA:

Routledge, 2005.

Barton S. Michael. “Gentrification and Violent Crime in New York

City.” Crime & Delinquency 2016, Vol. 62(9) 1180 –1202.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128714549652

“Burra Charter-The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural

Significance.” Australia ICOMOS Incorporated International Council

on Monuments and Sites, 2013.

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. The Gentrification Debates: a Reader.

London: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

Capps, Kriston, and Kriston Capps. “Study: No Link between

Gentrification and Displacement in NYC.” CityLab, August 14, 2019.

https://www.citylab.com/equity/2019/07/gentrification-displacement-

link-children-nyc-medicaid-data/594250/.

Chau K. W., Lennon H. T. Choy, and Ho Yin Lee. “Institutional

arrangements for urban conservation.” J Hous and the Built Environ

(2018) 33:455–463 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9609-2.

DeSena, N., Judith. Gentrification and Inequality in Brooklyn: The

New Kids on the Block. New York, USA: Lexington Books, 2009.

Huynh, M., and A. R. Maroko. “Gentrification and Preterm Birth in

New York City, 2008–2010.” Journal of Urban Health 91, no. 1

(November 2013): 211–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-013-9823-x.

Jokilehto, Jukka. “A History of Architectural Conservation.” Oxford, UK:

Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

ARCH 411_ Section II

Akın 12

Lasky, Julie. “Fort Greene, Brooklyn: Riding the Wave of

Gentrification.” The New York Times. New York USA: November 6, 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/realestate/fort-greene-brooklyn-

riding-the-wave-of-gentrification.html.

Lees, Loretta Conway. A Pluralistic and Comparative Analysis of

Gentrification in London and New York. Great Britain: University of

Edinburgh, 1995.

Lees, Loretta, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wyly. Gentrification. New York,

USA: Routledge, 2008.

“Mapping Displacement and Gentrification in the New York

Metropolitan Area.” Mapping Displacement and Gentrification in the

New York Metropolitan Area | Urban Displacement Project. Accessed

November 26, 2019. https://www.urbandisplacement.org/maps/ny.

Orbasli, Aylin. Tourists in Historic Towns Urban Conservation and

Heritage Management. London, England: E & FN Spon, 2000.

Roca, Pere, Lourenc̦

o Paulo B., and Angelo Gaetani. Historic

Construction and Conservation: Materials, Systems and Damage. New

York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

ARCH 411_ Section II

You might also like

- DISC LeadershipDocument55 pagesDISC LeadershipHado ReemNo ratings yet

- Reexamining Cultural Resource ManagementDocument15 pagesReexamining Cultural Resource ManagementAngel CebrerosNo ratings yet

- PGS Lecture Materials (Updates)Document30 pagesPGS Lecture Materials (Updates)emer_halili100% (2)

- Hamlet Essay Grade 12 EngDocument5 pagesHamlet Essay Grade 12 Engapi-390744685No ratings yet

- NCM 109 Aug. 21, 2018Document10 pagesNCM 109 Aug. 21, 2018rimeoznekNo ratings yet

- Japanese Vernacular ArchitectureDocument86 pagesJapanese Vernacular Architecturefcharaf100% (3)

- Zones of Tradition - Places of Identity: Cities and Their HeritageFrom EverandZones of Tradition - Places of Identity: Cities and Their HeritageNo ratings yet

- Stop Loss Placement &managementDocument14 pagesStop Loss Placement &managementanass ouajarNo ratings yet

- Beyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner CitiesFrom EverandBeyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner CitiesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Importance of Vernacular ArchitectureDocument23 pagesImportance of Vernacular ArchitectureRavnish Batth94% (16)

- World Heritage: Defining The Outstanding Universal ValueDocument10 pagesWorld Heritage: Defining The Outstanding Universal Valuelafitte81No ratings yet

- Full Paper ID103Document10 pagesFull Paper ID103Mariane MeshakaNo ratings yet

- Historicizing Early Modernity - Decolonizing Heritage: Conservation Design Strategies in Postwar BeirutDocument19 pagesHistoricizing Early Modernity - Decolonizing Heritage: Conservation Design Strategies in Postwar BeirutGeorges KhawamNo ratings yet

- SUVREMENItrendovi KONZERVACIJADocument11 pagesSUVREMENItrendovi KONZERVACIJApostiraNo ratings yet

- Urbansci 04 00059 v2Document15 pagesUrbansci 04 00059 v2mohamedr55104No ratings yet

- 2687-Article Text-7590-1-10-20181027Document9 pages2687-Article Text-7590-1-10-20181027angélicaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Genius Loc I On Urban Renewal PoliciesDocument21 pagesThe Impact of Genius Loc I On Urban Renewal Policiestaqwa alhasaniNo ratings yet

- The Uses of Reconstructing Heritage in China: Tourism, Heritage Authorization, and Spatial Transformation of The Shaolin TempleDocument21 pagesThe Uses of Reconstructing Heritage in China: Tourism, Heritage Authorization, and Spatial Transformation of The Shaolin TempleakshayaNo ratings yet

- Towards A Holistic Narration of Place: Conserving Natural and Built Heritage at The Humble Administrator's Garden, ChinaDocument15 pagesTowards A Holistic Narration of Place: Conserving Natural and Built Heritage at The Humble Administrator's Garden, Chinaldelosreyes122No ratings yet

- City, Culture and Society: Lachlan B. BarberDocument7 pagesCity, Culture and Society: Lachlan B. BarberChun Man Dixon LEONGNo ratings yet

- MASON Fixing Historic PreservationDocument9 pagesMASON Fixing Historic PreservationAna Raquel MenesesNo ratings yet

- H Planning Urban Tourism Conservation Nasser 2003Document13 pagesH Planning Urban Tourism Conservation Nasser 2003Mohammed Younus AL-BjariNo ratings yet

- Factors of Effective Conservation and Management of Historic Buildings Gerryshom Munala, Bernard Otoki Moirongo, & Paul Mwangi Maringa Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, P.O. Box 62000 – 00200, Nairobi, Kenya,Email: : munalag@yahoo.com, bmoirongo@yahoo.com, pmmaringa@yahoo.co.uk, published vol 1 (1) 2006 of the African Journal of Design & Construction (AJDC)Document15 pagesFactors of Effective Conservation and Management of Historic Buildings Gerryshom Munala, Bernard Otoki Moirongo, & Paul Mwangi Maringa Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, P.O. Box 62000 – 00200, Nairobi, Kenya,Email: : munalag@yahoo.com, bmoirongo@yahoo.com, pmmaringa@yahoo.co.uk, published vol 1 (1) 2006 of the African Journal of Design & Construction (AJDC)Paul Mwangi MaringaNo ratings yet

- Imageability SilvaCHS2009FinalDocument10 pagesImageability SilvaCHS2009Finalpatricia de roxasNo ratings yet

- H Planning - Urban - Tourism - Conservation - Nasser 2003 PDFDocument13 pagesH Planning - Urban - Tourism - Conservation - Nasser 2003 PDFDewangga Putra AdiwenaNo ratings yet

- Linking Intangible and Tangible HeritageDocument8 pagesLinking Intangible and Tangible HeritageBhumika YadavNo ratings yet

- Chapter3 9781138482555 Proofs ArchitecturalExcellenceinIslamicSocieties Salama El-AshmouniDocument7 pagesChapter3 9781138482555 Proofs ArchitecturalExcellenceinIslamicSocieties Salama El-AshmouniAbdouhNo ratings yet

- EN - Cultural MappingTooklit - UpdatedDocument14 pagesEN - Cultural MappingTooklit - UpdatedCandy LawNo ratings yet

- Conservation of The Urban Heritage To Conserve The Sense of Place, A Case Study Misurata City, LibyaDocument12 pagesConservation of The Urban Heritage To Conserve The Sense of Place, A Case Study Misurata City, LibyaBoonsap WitchayangkoonNo ratings yet

- Urban Empty Spaces. Contentious Places For Consensus-BuildingDocument16 pagesUrban Empty Spaces. Contentious Places For Consensus-BuildingStephenson MagalhãesNo ratings yet

- Unpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and TypologDocument20 pagesUnpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and Typologtamara.alshaweesh55No ratings yet

- TEX 8 - Avrami Et Al 2000 Solo ReportDocument16 pagesTEX 8 - Avrami Et Al 2000 Solo ReportmarcelanabusimakecpaNo ratings yet

- Langfield - Logan - Cultural Diversity and Human RigthsDocument247 pagesLangfield - Logan - Cultural Diversity and Human Rigthsgabriel.pnnNo ratings yet

- Salvador ViñasDocument4 pagesSalvador ViñasJuliana BragançaNo ratings yet

- Historic Area AssessmentDocument41 pagesHistoric Area AssessmentMythili MadhuNo ratings yet

- The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) As A New Approach To The Conservation of Historic CitiesDocument7 pagesThe Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) As A New Approach To The Conservation of Historic CitiesbramNo ratings yet

- On The Sustainability of LocalDocument32 pagesOn The Sustainability of LocalAnanya MishraNo ratings yet

- Emulating VernacularDocument15 pagesEmulating VernacularBilly 'EnNo ratings yet

- Innovative Multidisciplinary Methodology For The Analysis of Traditional Marginal ArchitectureDocument31 pagesInnovative Multidisciplinary Methodology For The Analysis of Traditional Marginal ArchitectureDaniaNo ratings yet

- Sustainability-14-00191-V4 - Scugnizzo Liberato FAVADocument16 pagesSustainability-14-00191-V4 - Scugnizzo Liberato FAVAFrancesco ChiacchieraNo ratings yet

- The Right To Landscape: Social Sustainability and The Conservation of The State Theatre, Hong KongDocument16 pagesThe Right To Landscape: Social Sustainability and The Conservation of The State Theatre, Hong KongEduardo PortugalNo ratings yet

- Heritage and CivicismDocument13 pagesHeritage and CivicismSangeeta MittalNo ratings yet

- Land 09 00264 v2Document16 pagesLand 09 00264 v2Irene RamosNo ratings yet

- A Review of Definition and Classification of Heritage Buildings and Framework For TheirDocument6 pagesA Review of Definition and Classification of Heritage Buildings and Framework For TheirFarah ChedidNo ratings yet

- 220 Landzelius Contested Representations Signification in The Built Environment PDFDocument24 pages220 Landzelius Contested Representations Signification in The Built Environment PDFJavier LuisNo ratings yet

- Foreign Objects: Architectural History in The Age of GlobalizationDocument5 pagesForeign Objects: Architectural History in The Age of GlobalizationAlexander MesaNo ratings yet

- 002-Conflict, Reconstruction and IDocument4 pages002-Conflict, Reconstruction and IhajijojonNo ratings yet

- ArchitectureDocument1 pageArchitectureAhir NikhilNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Site Management Theory STDocument34 pagesArchaeological Site Management Theory STdvfbckqfwqNo ratings yet

- Contextualism and SustainabilityDocument20 pagesContextualism and SustainabilityYoungjk KimNo ratings yet

- The Role of Spatial Networks in The HistoryDocument25 pagesThe Role of Spatial Networks in The HistoryMaryNo ratings yet

- Journal of Urban Development and Management Integrating The Biophilia Concept Into Urban Planning: A Case Study of Kufa City, IraqDocument11 pagesJournal of Urban Development and Management Integrating The Biophilia Concept Into Urban Planning: A Case Study of Kufa City, Iraqعلي حسين عليNo ratings yet

- A Sense of Place in Public HousingDocument19 pagesA Sense of Place in Public Housingnurhikmahpaddiyatu100% (1)

- House Form & Culture: Amos RapoportDocument11 pagesHouse Form & Culture: Amos RapoportSneha PeriwalNo ratings yet

- Buildings As History: The Place of Collective Memory in The Study of Historic PreservationDocument20 pagesBuildings As History: The Place of Collective Memory in The Study of Historic PreservationjoyNo ratings yet

- ARCH 411 - Assignment I I - Sümeyra Didar AkınDocument5 pagesARCH 411 - Assignment I I - Sümeyra Didar AkınDidar AkınNo ratings yet

- The Meanings of Historic Urban Landscape PDFDocument2 pagesThe Meanings of Historic Urban Landscape PDFAliaa Ahmed ShemariNo ratings yet

- Thesis Design Research Process: Reviving Culture Through ArchitectureDocument17 pagesThesis Design Research Process: Reviving Culture Through ArchitectureRAFIA IMRANNo ratings yet

- A Structural Project: Redevelopment of The Historic Center of WuhuDocument19 pagesA Structural Project: Redevelopment of The Historic Center of Wuhuradhika goelNo ratings yet

- 77 425S 203 PDFDocument21 pages77 425S 203 PDFvigneshNo ratings yet

- USICOMOSSymposium Keynote Speech PrintversionDocument15 pagesUSICOMOSSymposium Keynote Speech PrintversionFroilan CelestialNo ratings yet

- A Geography of Big Things - Jane JacobsDocument27 pagesA Geography of Big Things - Jane JacobsFranco Martín LópezNo ratings yet

- Veldpausetal - Urban Heritage Putting The Past Into Future - 2013Document17 pagesVeldpausetal - Urban Heritage Putting The Past Into Future - 2013graditeljskoNo ratings yet

- Essay The Idea of DesignDocument3 pagesEssay The Idea of DesignBob Peniel InapanuriNo ratings yet

- Can We Afford Urban Conservation? - Lahore Walled City: Author: Ar./Plnr Azhar M. SualehiDocument17 pagesCan We Afford Urban Conservation? - Lahore Walled City: Author: Ar./Plnr Azhar M. SualehiAzhar M. SualehiNo ratings yet

- RC Axial MembersDocument25 pagesRC Axial MembersDidar AkınNo ratings yet

- Shear forces and bending moments usually co-exist on beams.: normal stress (σ) shear stress (τ)Document23 pagesShear forces and bending moments usually co-exist on beams.: normal stress (σ) shear stress (τ)Didar AkınNo ratings yet

- Cross Section: ARCH 332 - Bilkent University - İsmail Ozan DemirelDocument48 pagesCross Section: ARCH 332 - Bilkent University - İsmail Ozan DemirelDidar AkınNo ratings yet

- Arch 290Document5 pagesArch 290Didar AkınNo ratings yet

- ARCH 411 - Assignment I I - Sümeyra Didar AkınDocument5 pagesARCH 411 - Assignment I I - Sümeyra Didar AkınDidar AkınNo ratings yet

- Architecture Poster Arch418Document1 pageArchitecture Poster Arch418Didar AkınNo ratings yet

- Arch 342 Project IDocument9 pagesArch 342 Project IDidar AkınNo ratings yet

- Lack of Civic SenseDocument7 pagesLack of Civic SenseRam CharanNo ratings yet

- LP Moral IssueDocument5 pagesLP Moral IssueDaryll Jade PoscabloNo ratings yet

- 2021 - PHS Form 1Document4 pages2021 - PHS Form 1Nile UyNo ratings yet

- 02 - Cornelia MUNTEANU Inconvenientele Anormalei VecinatatiDocument30 pages02 - Cornelia MUNTEANU Inconvenientele Anormalei VecinatatiAdina SimonaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Law of ContractsDocument15 pagesIslamic Law of ContractsWajid MuradNo ratings yet

- Module 3.2 - The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesDocument10 pagesModule 3.2 - The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesMarkhill Veran TiosanNo ratings yet

- La Liga Humanitaria 1891-1919Document64 pagesLa Liga Humanitaria 1891-1919Almirante211No ratings yet

- The Ethics of Artificial IntelligenceDocument2 pagesThe Ethics of Artificial IntelligenceGalih PutraNo ratings yet

- Nursing Shortages A Paper On The Reasons Ethics How To Fix This DevelopmentDocument10 pagesNursing Shortages A Paper On The Reasons Ethics How To Fix This Developmentapi-608672872No ratings yet

- Confidentiality Undertaking StudentDocument1 pageConfidentiality Undertaking StudentTzuNaMiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 BGN352Document4 pagesAssignment 2 BGN352Syamimi HanaNo ratings yet

- Work Values: Firly Dina Arofah Yuniatri Intan Kusuma NingrumDocument17 pagesWork Values: Firly Dina Arofah Yuniatri Intan Kusuma NingrumFirly Dina ArofahNo ratings yet

- A Leader's ValuesDocument20 pagesA Leader's ValuesAndroids17No ratings yet

- Faculty of Communication & Media StudiesDocument5 pagesFaculty of Communication & Media StudiesShamimie syahidaNo ratings yet

- Schaefer-Foundationaless Human N RightsDocument25 pagesSchaefer-Foundationaless Human N RightsJesúsNo ratings yet

- Assingment On Law of Labour 2Document5 pagesAssingment On Law of Labour 2Proshad BiswasNo ratings yet

- Guaranteed AcceptanceDocument15 pagesGuaranteed AcceptanceRizalman JoharNo ratings yet

- Abdul Kalam On Youth and EducationDocument7 pagesAbdul Kalam On Youth and EducationThomas Kuzhinapurath100% (2)

- Purposive Communication & Ethics ExaminationDocument4 pagesPurposive Communication & Ethics ExaminationNovie Jane LodiomonNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Human Need: Len Doyal and Ian GoughDocument5 pagesA Theory of Human Need: Len Doyal and Ian GoughJesica ortizNo ratings yet

- Applied Epistemology: Prospects and Problems: by Søren Harnow Klausen, University of Southern DenmarkDocument38 pagesApplied Epistemology: Prospects and Problems: by Søren Harnow Klausen, University of Southern DenmarkFelipe ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

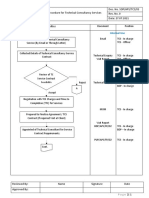

- SOP APS TCS 03 Procedure For Technical Consultancy ServicesDocument2 pagesSOP APS TCS 03 Procedure For Technical Consultancy ServicesPrakash PatelNo ratings yet

- Ge6075 Professional Ethics in Engineering Unit 2Document51 pagesGe6075 Professional Ethics in Engineering Unit 2sathya priyaNo ratings yet

- Citizen Advancement TrainingDocument4 pagesCitizen Advancement TrainingJp Coquia100% (6)

- Mr. Moktan Delivering Speech On Dashain Celebration DayDocument2 pagesMr. Moktan Delivering Speech On Dashain Celebration DayDeependra SilwalNo ratings yet