Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Association of Systemic Inflammation and Sarcopenia

Uploaded by

Tícia RanessaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Association of Systemic Inflammation and Sarcopenia

Uploaded by

Tícia RanessaCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Oncology | Original Investigation

Association of Systemic Inflammation and Sarcopenia

With Survival in Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer

Results From the C SCANS Study

Elizabeth M. Cespedes Feliciano, ScD, MSc; Candyce H. Kroenke, ScD, MPH; Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, MD, MPH;

Carla M. Prado, PhD; Patrick T. Bradshaw, PhD, MS; Marilyn L. Kwan, PhD; Jingjie Xiao, MSc; Stacey Alexeeff, PhD;

Douglas Corley, MD, PhD; Erin Weltzien; Adrienne L. Castillo, RD; Bette J. Caan, DrPH

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE Systemic inflammation and sarcopenia are easily evaluated, predict mortality in

many cancers, and are potentially modifiable. The combination of inflammation and

sarcopenia may be able to identify patients with early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC) with poor

prognosis.

OBJECTIVE To examine associations of prediagnostic systemic inflammation with at-diagnosis

sarcopenia, and determine whether these factors interact to predict CRC survival, adjusting

for age, ethnicity, sex, body mass index, stage, and cancer site.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A prospective cohort of 2470 Kaiser Permanente

patients with stage I to III CRC diagnosed from 2006 through 2011.

EXPOSURES Our primary measure of inflammation was the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

(NLR). We averaged NLR in the 24 months before diagnosis (mean count = 3 measures; mean

time before diagnosis = 7 mo). The reference group was NLR of less than 3, indicating low or

no inflammation.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Using computed tomography scans, we calculated skeletal

muscle index (muscle area at the third lumbar vertebra divided by squared height). Sarcopenia

was defined as less than 52 cm2/m2 and less than 38 cm2/m2 for normal or overweight men

and women, respectively, and less than 54 cm2/m2 and less than 47 cm2/m2 for obese men

and women, respectively. The main outcome was death (overall or CRC related).

RESULTS Among 2470 patients, 1219 (49%) were female; mean (SD) age was 63 (12) years.

An NLR of 3 or greater and sarcopenia were common (1133 [46%] and 1078 [44%],

respectively). Over a median of 6 years of follow-up, we observed 656 deaths, 357 from CRC.

Increasing NLR was associated with sarcopenia in a dose-response manner (compared with

NLR < 3, odds ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.10-1.67 for NLR 3 to <5; 1.47; 95% CI, 1.16-1.85 for NLR ⱖ 5;

P for trend < .001). An NLR of 3 or greater and sarcopenia independently predicted overall Author Affiliations: Division of

Research, Kaiser Permanente

(hazard ratio [HR], 1.64; 95% CI, 1.40-1.91 and HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10-1.53, respectively) and Northern California, Oakland,

CRC-related death (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.39-2.12 and HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.13-1.78, respectively). California (Cespedes Feliciano,

Patients with both sarcopenia and NLR of 3 or greater (vs neither) had double the risk of Kroenke, Kwan, Alexeeff, Corley,

Weltzien, Castillo, Caan); Department

death, overall (HR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.70-2.65) and CRC related (HR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.79-3.29).

of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber

Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Prediagnosis inflammation was associated with at-diagnosis School, Boston, Massachusetts

sarcopenia. Sarcopenia combined with inflammation nearly doubled risk of death, suggesting (Meyerhardt); Department of

Agricultural, Food, and Nutritional

that these commonly collected biomarkers could enhance prognostication. A better Sciences, University of Alberta,

understanding of how the host inflammatory/immune response influences changes in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada (Prado,

skeletal muscle may open new therapeutic avenues to improve cancer outcomes. Xiao); Division of Epidemiology,

School of Public Health, University

of California–Berkeley (Bradshaw).

Corresponding Author: Elizabeth M.

Cespedes Feliciano, ScD, MSc, Division

of Research, Kaiser Permanente

Northern California, 2000 Broadway,

JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2319 5th Floor, Oakland, CA 94612

Published online August 10, 2017. (elizabeth.m.cespedes@kp.org).

(Reprinted) E1

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Research Original Investigation Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer

I

dentifying which patients with early-stage cancer are at high

risk of adverse treatment outcomes and premature mortal- Key Points

ity is a clinical priority. Two novel prognostic indicators

Question Is systemic inflammation (manifest as elevated

receiving increasing attention across cancer types are sarco- neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio) associated with sarcopenia

penia (low skeletal muscle mass)1 and an elevated neutrophil- (reduced skeletal muscle mass), and are these 2 risk factors

to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR, a measure of systemic inflam- combined associated with survival after colorectal cancer (CRC)

mation).2 Sarcopenia predicts poor surgical outcomes,3 treatment diagnosis?

toxic effects,4-6 and reduced survival.1,7 Routine diagnostic Findings In a cohort of 2470 patients with nonmetastatic CRC,

imaging using computed tomography (CT) can be used to ac- elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio before diagnosis was

curately quantify muscle mass, revealing sarcopenia that might associated with at-diagnosis sarcopenia in a dose-response

otherwise go undetected. Similarly, pretreatment values manner; patients with both sarcopenia and neutrophil to

of NLR 2 and related blood biomarkers (eg, platelet-to- lymphocyte ratio of 3 or greater (vs neither) had double the risk of

death overall and from CRC.

lymphocyte ratio [PLR]8 and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

[LMR]9) are commonly measured and predict treatment re- Meaning Sarcopenia and inflammation predicted worse CRC

sponse and survival. Whereas both sarcopenia and inflamma- prognosis regardless of stage. Because these 2 biomarkers are

tion can be evaluated with existing clinical data and may be commonly collected and potentially modifiable, they have high

potential for clinical use in prognostication and possibly in guiding

modifiable, the relationship between these 2 factors and their

intervention.

independent associations with survival are not well studied.

Recent trials treating cachexia with ω-3 fatty acid supple-

mentation and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs10,11 un- cluded 3276 Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC)

derscore the importance of systemic inflammation as a driver health plan members who received a diagnosis of stage I to III

of muscle degradation in patients with late-stage disease.12,13 CRC between 2006 and 2011 who underwent surgical resection

Proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors released as part and had an abdominal CT scan at diagnosis of sufficient image

of the systemic inflammatory response to the tumor have pro- quality to analyze. We further restricted the sample to those with

found catabolic effects on host metabolism, which lead to prediagnostic NLR values available from clinically acquired labo-

muscle breakdown.14 Low muscularity could contribute to lo- ratory data (n = 2470). Patients included and excluded due to

cal inflammation in the muscle, leading to further breakdown insufficient data were similar with respect to BMI, race/ethnicity,

and driving systemic inflammation.15 In turn, this inflamma- sex, age, stage, and survival duration. The study was approved

tory cycle could enhance tumor aggressiveness or reduce treat- by the KPNC Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was

ment response, impairing the transition into survivorship.16,17 waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Whereas lower muscle mass also has deleterious conse-

quences for morbidity and/or mortality in patients with early- Body Composition and BMI

stage disease,1,7 little research examines whether systemic in- We selected the height and weight obtained closest to the CT

flammation predicts muscle mass in early-stage cancer. scan measured by KPNC medical assistants and computed BMI,

To our knowledge, no prior study examines combined as- categorized as less than 20, 20 to less than 25, 25 to less than

sociations of the host systemic inflammatory response and sar- 30, 30 to less than 35, or at least 35. “At-diagnosis” muscle mass

copenia with colorectal cancer (CRC) survival. Not only are these was assessed from a CT scan taken before chemotherapy or ra-

factors important as prognostic indicators, they are also poten- diation therapy (if received). On average, scans were 2 days be-

tially modifiable. Colorectal cancer, a leading cause of cancer fore diagnosis (range, −2 to 4 months; 1951 [79%] presurgical).

death,18 is an ideal setting in which to evaluate this relation- A single, trained researcher at the University of Alberta (J.X.)

ship because of the availability of CT images and laboratory selected the third lumbar vertebra and analyzed the cross-

blood biomarkers. Among 2470 patients with a diagnosis of sectional area of muscle in centimeters squared according to pre-

American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I to III CRC, we ex- defined tissue-specific Hounsfield units ranges using Slice-O-

amined the association of prediagnostic NLR with at- Matic Software, version 5.0 (Tomovision).22 Single-slice muscle

diagnosis sarcopenia. Subsequently, we assessed the indepen- area at the third lumbar vertebra is strongly correlated with

dent and combined associations of these risk factors with whole-body volume of muscle tissue23 and has been exten-

survival. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to examine sively used in oncology settings.24,25 As in prior publications,7,26

whether associations were consistent across other inflamma- we used optimal stratification to select BMI and sex-specific cut-

tory biomarkers and subgroups defined by body mass index offs for skeletal muscle index (muscle area in centimeters

(BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in me- squared divided by squared height in meters squared) to de-

ters squared), stage, age, and sex. fine sarcopenia: for normal or overweight patients (BMI < 30),

these were less than 52 cm2/m2 for men and less than 38 cm2/m2

for women, while for obese patients (BMI ≥ 30), these were less

than 54 cm2/m2 for men and less than 47 cm2/m2 for women.

Methods

Study Population Markers of Systemic Inflammation

The “C SCANS” (Colorectal Cancer: Sarcopenia, Cancer, and Near- Our primary measure of systemic inflammation was NLR from

term Survival) cohort, described in detail elsewhere,7,19-21 in- laboratory values obtained as part of routine blood tests (all

E2 JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaoncology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer Original Investigation Research

measurements were prior to the diagnostic scan, surgery, or other Finally, given the existing literature suggesting associa-

treatment). We averaged all available NLR measures in the 24 tions of BMI category, sex, age, and stage at diagnosis with CRC

months prior to diagnosis (mean number of NLR measures was survival, we evaluated the main associations of each variable

3; mean interval before diagnosis was 7 months) and categorized with survival, as well as possible interactions of these vari-

this average using standard cutoffs to define “normal” (<3), ables with NLR and/or sarcopenia using stratified analyses and

“moderate” (3 to <5), and “high” (≥5) inflammation.2 Second- LRTs.

ary biomarkers of inflammation (eTable 1 in the Supplement) Two-sided P < .05 was considered significant. We used Sta-

were available at the same time point; we averaged and catego- tistical Analysis Software, version 9.3 (SAS, Inc) for all statis-

rized available measures using clinically relevant cutoffs (PLR tical analyses.

of <150, 150 to <300, or ≥300 and LMR of <2, 2 to <3, 3 to <4, or

≥4 wherein higher PLR and lower LMR indicate more severe

inflammation).8,9 Serum albumin level, of particular interest as

a marker not only of nutritional status but also of systemic in-

Results

flammation, was available for a subset of 716 participants, and Table 1 presents the characteristics of 2470 patients with non-

dichotomized at less than 3.5 g/dL (the cutoff for hypoalbumin- metastatic CRC by category of prediagnostic NLR. Patients with

emia; to convert to grams per liter, multiply by 10).14 a higher NLR in the 24 months prior to diagnosis had less fa-

vorable values for all other markers of systemic inflamma-

Other Covariates and End Points tion: higher PLR, lower LMR, and lower serum albumin level.

We reviewed the KPNC electronic medical record and Cancer Patients with greater systemic inflammation prior to diagno-

Registry for information on disease stage, tumor characteris- sis were older, more likely to be female, to be non-Hispanic

tics, surgery, treatment (chemotherapy or radiation therapy), white, to have colon (vs rectal) cancer, and to have stage II or

and demographic (eg, age, race/ethnicity, and sex) and health III (vs I) cancer. A majority were overweight (864 [35%]) or

characteristics (Charlson comorbidity index). We obtained data obese (786 [32%]). The prevalence of sarcopenia and prediag-

on overall and CRC-specific mortality from the KPNC mortal- nosis NLR of 3 or greater were 46% (n = 1133) and 44%

ity file, composed of data from the California Department of (n = 1078), respectively.

Vital Statistics, US Social Security Administration, and KPNC A higher prediagnostic NLR was associated in a dose-

health care utilization data. response manner with the odds of sarcopenia independent of

race/ethnicity, cancer site, age, stage, and BMI: compared with

Statistical Analysis patients with NLR of less than 3, the odds ratios (ORs) for sar-

In exploratory analyses, we tabulated descriptive statistics copenia were 1.35 (95% CI, 1.10-1.67) for NLR of 3 to less than

(mean [SD] and percentages). Next, we conducted logistic re- 5 and 1.47 (95% CI, 1.16-1.85) for NLR of 5 or greater (P for trend

gression for categorical NLR (<3, 3-5, ≥5) as a predictor of sar- across categories, <.001). Results were consistent across other

copenia (yes or no), with the P value for a linear trend evalu- markers of systemic inflammation, with higher PLR, lower

ated by treating the median of each NLR category in LMR, and hypoalbuminemia all associated with higher odds

multivariable models as a continuous predictor. Using multi- of sarcopenia (eTable 1 in the Supplement), and, in continu-

variable-adjusted linear regression, we evaluated differences ous analyses, with lower skeletal muscle index (eTable 2 in the

in muscle in centimeters squared by category of NLR and sec- Supplement). Furthermore, the association of elevated NLR

ondary biomarkers. Models were adjusted for race/ethnicity, with increased odds of sarcopenia was consistent across stage,

sex, cancer site, and at-diagnosis values of age, BMI category, age, and sex (no evidence of interaction) (eTable 3 in the

and cancer stage. Supplement).

In analyses in which survival was the outcome, we cross- As observed in the Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure), patients

classified NLR of 3 or greater and sarcopenia in 4 categories (in- with NLR of 3 or greater and sarcopenia had the worst sur-

flammation only, sarcopenia only, both, or neither [reference]) vival, whereas patients with NLR of less than 3 and no sarco-

and calculated Kaplan-Meier curves. Next, we examined NLR penia survived the longest (log-rank P < .001) (Figure). eFig-

of 3 or greater and sarcopenia as independent (mutually ad- ure 1 in the Supplement shows the multivariable-adjusted results

justed) predictors of survival in multivariable-adjusted Cox pro- for overall survival in each category defined by the presence (or

portional hazards models. Models were adjusted for race/ absence) of NLR of 3 or greater and/or sarcopenia. These risks

ethnicity, sex, cancer site, and at-diagnosis values of age, BMI are overlaid on the distribution of the categories according to

category, and cancer stage. We further adjusted for treatment age at diagnosis, illustrating that although sarcopenia and in-

(chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy) and Charlson comor- flammation were more common in older patients, both condi-

bidity index. Participants were observed from diagnosis until tions occurred across age groups and were associated with sur-

death from any cause, death from CRC, or the end of follow-up vival: for example, 200 (16%) of patients younger than 65 years

(December 31, 2015). For overall mortality, individuals alive at at diagnosis had both sarcopenia and inflammation. Survival

the end of follow-up were censored at that time. For CRC mor- probabilities for NLR of 3 or greater and sarcopenia are shown

tality, individuals who died of other causes during follow-up separately in eFigures 2 and 3 in the Supplement, respectively.

were censored at that time. Evaluations for the presence of mul- In multivariable analyses, the interaction of sarcopenia with

tiplicative interaction between NLR of 3 or greater and sarco- NLR was nonsignificant. Thus, we report the independent (mu-

penia used the likelihood ratio test (LRT). tually adjusted) associations of each risk factor with overall and

jamaoncology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 E3

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Research Original Investigation Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer

Table 1. Characteristics by Level of Systemic Inflammation Prior to Diagnosis in 2470 Patients

With Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

NLR Prior to CRC Diagnosis

<3 3 to <5 ≥5

a

Characteristic (n = 1337) (n = 646) (n = 487)

NLR, median (IQR) 2.0 (1.6-2.4) 3.8 (3.4-4.3) 6.9 (5.8-9.9)

Other inflammatory markers, median (IQR)

Platelet to lymphocyte ratio 129 (103-166) 185 (150-236) 273 (205-370)

Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio 3.6 (3.0-4.6) 2.5 (2.0-3.1) 1.8 (1.3-2.4)

Albumin level, g/dLb 4.2 (3.8-4.4) 3.9 (3.5-4.2) 3.7 (3.1-4.2)

Time from NLR to scan, mean (SD), mo −6 (6) −5 (6) −5 (6)

Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y 62 (11) 63 (12) 65 (12)

Charlson comorbidity score, mean (SD) 0.8 (1.3) 1.0 (1.6) 1.4 (1.8)

Body mass index, mean (SD) 28 (6) 28 (6) 28 (7)

Race/ethnicity, No. (%)

Non-Hispanic white 842 (63) 433 (67) 346 (71)

Black 120 (9) 45 (7) 24 (5)

Hispanic 160 (12) 84 (13) 34 (7)

Asian/Pacific islander 214 (16) 84 (13) 78 (16)

Other 13 (1) 6 (1) 5 (1)

Sex, No. (%)

Female 615 (46) 336 (52) 268 (55)

Male 722 (54) 310 (48) 219 (45) Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile

Cancer stage, No. (%) range; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte

ratio.

I 428 (32) 155 (24) 107 (22)

SI conversion factor: To convert

II 388 (29) 233 (36) 185 (38) albumin to grams per liter, multiply

III 508 (38) 258 (40) 200 (41) by 10.

a

Cancer site, No. (%) Percentages may not total 100

because of rounding.

Colon 936 (70) 491 (76) 394 (81)

b

Albumin level was only available on

Rectum 401 (30) 155 (24) 93 (19)

a subset of 716 patients.

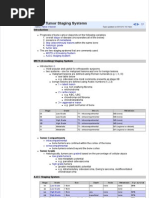

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Survivorship Function According to Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio

and Sarcopenia Status in 2470 Patients With Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer

1.0

0.9

Overall Survival Probability

0.8

NLR <3; no sarcopenia

0.7

NLR <3; sarcopenia

NLR ≥3; no sarcopenia

0.6

NLR ≥3; sarcopenia

0.5

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Time Since Diagnosis, y

No. at risk

NLR <3; no sarcopenia 819 789 743 516 225 20

NLR <3; sarcopenia 560 481 435 282 118 14

NLR ≥3; no sarcopenia 517 511 456 321 149 15

NLR ≥3; sarcopenia 561 478 412 277 137 13 NLR indicates neutrophil to

lymphocyte ratio.

CRC-specific survival (Table 2) in the form of hazard ratios (HRs). CI, 1.13-1.78, respectively). Under the model of independent

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio of 3 or greater and sarcopenia effects (Table 2), a patient with both sarcopenia and NLR of 3

independently predicted overall survival (HR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.40- or greater was estimated to have much worse overall (HR, 2.12;

1.91 and HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10-1.53, respectively), as well as CRC- 95% CI, 1.70-2.65) and CRC-specific survival (HR, 2.43; 95% CI,

specific survival (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.39-2.12 and HR, 1.42; 95% 1.79-3.29) than a patient with neither risk factor.

E4 JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaoncology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer Original Investigation Research

Table 2. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Sarcopenia, Table 3. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Sarcopenia,

and Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Survival in 2470 Patients and Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Survival Stratified by Body Mass Index,

With Nonmetastatic CRCa Stage, Age, and Sex (n = 2470)a

HR (95% CI)b HR (95% CI)b

Independent, Mutually Overall Survival CRC Survival Stratification Variable Overall Survival CRC Survival

Adjusted Associations (674 Events) (357 Events)

BMI

Sarcopenia

<20 1.63 (0.48-5.59) 4.02 (0.60-27.06)

Yes 1.28 (1.10-1.53) 1.42 (1.13-1.78)

20 to <25 2.53 (1.66-3.87) 3.24 (1.81-5.81)

No [1 Reference] [1 Reference]

25 to <30 1.81 (1.22-2.70) 2.01 (1.14-3.53)

NLR

30 to <35 2.30 (1.38-3.82) 2.07 (1.08-4.04)

≥3 1.64 (1.40-1.91) 1.71 (1.39-2.12)

≥35 2.95 (1.58-5.54) 2.78 (1.13-6.85)

<3 [1 Reference] [1 Reference]

Cancer stage

NLR ≥ 3 and sarcopenia

I 1.81 (1.07-3.09) 4.21 (1.45-12.23)

Both 2.12 (1.70-2.65) 2.43 (1.79-3.29)

II 1.54 (1.02-2.31) 1.79 (0.96-3.33)

Neither [1 Reference] [1 Reference]

III 2.79 (2.05-3.81) 2.56 (1.77-3.73)

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. Age at diagnosis, y

a

Cox proportional hazards models adjust for race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, <65 1.65 (1.15-2.37) 1.70 (1.09-2.68)

Asian/Pacific islander, other, or non-Hispanic white), cancer site (colon or

rectum), and at-diagnosis values of age (years), body mass index category (<20, ≥65 2.32 (1.75-3.08) 3.15 (2.05 4.84)

20 to <25, 25 to <30, 30 to <35, or ⱖ35; calculated as weight in kilograms Sex

divided by height in meters squared), sex (male or female), and stage (I, II, or III). Male 2.05 (1.49-2.83) 2.16 (1.39-3.35)

b

All HR estimates are from the same model in which sarcopenia and NLR of 3 or

Female 2.30 (1.67-3.17) 2.71 (1.74-4.23)

greater are mutually adjusted, assuming independent effects.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided

by height in meters squared); HR, hazard ratio.

As in previous studies, older age, later stage, and BMI of a

Cox proportional hazards models adjust for race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic,

greater than 35 were associated with lower overall survival (data Asian/Pacific islander, other, or non-Hispanic white), cancer site (colon or

not shown).19 However, there was no statistical evidence that rectum), and at-diagnosis values of age (years), BMI category (<20, 20 to <25,

25 to <30, 30 to <35, or ⱖ35), sex (male or female), and stage (I, II, or III),

BMI, stage, age, or sex modified the associations of NLR of 3 or unless stratified by those variables.

greater or sarcopenia with overall or CRC survival. Indeed, even b

All HRs compare patients with NLR of 3 or greater and sarcopenia vs patients

stage I (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.07-3.09) and younger patients (<65 with NLR less than 3 and no sarcopenia. All HR estimates are from the same

years, HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.15-2.37) with NLR of 3 or greater and model in which sarcopenia and NLR of 3 or greater are mutually adjusted,

assuming independent effects.

sarcopenia had nearly 2-fold increased risk of death from any

cause compared with patients of similar age and stage but with

neither condition (Table 3). cancers,1-5,8,9,14 most studies addressed them individually and

In sensitivity analyses, further adjustment for cancer treat- in patients with metastatic disease. Our study newly sug-

ment and Charlson comorbidity index did not alter the HRs; gests that similar processes occur in nonmetastatic CRC: el-

these variables were excluded from models. evated NLR in the months prior to diagnosis and other aber-

rations in inflammatory markers were present in nearly half

of patients, were associated with sarcopenia, and were pre-

dictive of survival. Furthermore, we observed similar results

Discussion regardless of stage at diagnosis, suggesting that muscle break-

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the re- down is not solely an artifact of increasing stage of disease;

lationship of markers of systemic inflammation to muscle mass some of the same mechanisms implicated in cancer cachexia

in CRC, and the only one to examine independent and com- may be operating earlier on in the cancer trajectory and lead-

bined associations with survival. In our cohort of 2470 pa- ing to relatively lower muscle mass long before the extreme

tients with stage I to III CRC, we found that greater NLR in the muscle loss that is the hallmark of cachexia. Our findings that

months prior to diagnosis was associated with sarcopenia at di- measures of inflammation were associated with sarcopenia and

agnosis. In addition, we found that the co-occurrence of high that the co-occurrence of inflammation and sarcopenia were

NLR and sarcopenia was associated with double the mortality associated with a high mortality risk are consistent with the

risk among patients with nonmetastatic CRC. Whereas both NLR limited prior literature on this topic. For example, a cross-

and sarcopenia increase with age and stage, they identify high- sectional study of 763 patients with stage I to IV CRC found that

risk subgroups of patients across the spectrum of age and stage. preoperative NLR and serum albumin levels were associated

Measures of inflammation and sarcopenia are easily obtain- with compromised muscle mass.29,30 With respect to sur-

able in the clinical setting and are each independently, and in vival, 1 prior study conducted in 117 men with small-cell lung

combination, powerful prognostic indicators in patients with cancer compared patients classified according to the co-

nonmetastatic cancer. occurrence of NLR and sarcopenia31; consistent with our re-

Although sarcopenia27 and systemic inflammation28 have sults, overall and progression-free survival were worse in the

previously been associated with prognosis in CRC and other group with both sarcopenia and elevated NLR.

jamaoncology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 E5

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Research Original Investigation Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer

We hypothesize that inflammation both underlies and is were independently associated with survival, we do not know

enhanced by muscle breakdown, part of a mutually reinforc- to what extent inflammation or sarcopenia are consequences

ing cycle conducive to cancer progression. Markers of sys- of a more aggressive tumor or a shared pathologic mecha-

temic inflammation such as NLR are correlated with elevated nism vs conditions that enhance tumor growth.

circulating concentrations of various cytokines in CRC,32 and We called the condition of low muscle “sarcopenia” in our

these are implicated in the activation of several catabolic path- study because patients had nonmetastatic disease and did not

ways. For example, cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and exhibit the degree of weight loss characteristic of cachexia.

interleukin 6 are produced by the tumor or surrounding cells However, we cannot truly distinguish whether patients (1) have

and promote protein degradation and decreased synthesis.33 low muscle because of normal aging (sarcopenia) and sarco-

Tumor necrosis factor inhibits skeletal myocyte differentia- penia exacerbates their mortality risk once they have cancer,

tion, promotes muscle atrophy,13,34 and contributes to insu- (2) are precachexic, although early in the trajectory, or (3) both.

lin resistance by impairing the insulin signaling pathway.35 In- Inflammation underlies both sarcopenia and cachexia, but re-

terleukin 6 can further reduce muscle protein synthesis.16 cent reviews43 suggest that the pathogenesis of muscle loss in

Increases in inflammatory cytokines can also lead to insulin normal aging differs from cancer cachexia, in which activa-

resistance and muscle wasting by activation of the ubiquitin- tion of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and nuclear fac-

proteasome proteolytic pathway,36 while muscle loss itself fur- tor–κB signaling result in rapid atrophy.44 Further research is

ther exacerbates insulin resistance.37,38 Low-grade, systemic needed to elucidate the biological sequence of inflammation,

inflammation caused by the tumor (and exacerbated possi- changes in body composition, and cancer progression.

bly by obesity or insulin resistance) could drive local inflam-

mation in the muscle. This, in turn, contributes further to sys- Limitations

temic inflammation and muscle degradation (through both To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the re-

increased proteolysis, manifesting in decreased muscle mass lationship between biomarkers of systemic inflammation and

[sarcopenia], and increased lipid deposition in skeletal muscle sarcopenia in CRC, and the only study to examine whether NLR

[measured via CT muscle radiodensity]).15 Although outside and sarcopenia are independently associated with CRC sur-

the scope of this analysis, excess fat may also play a role in this vival. The use of clinically acquired CT scans makes our ap-

vicious cycle: most of our patients were overweight or obese. proach replicable at low cost in clinical practice. This link to

Intramuscular lipid levels, increased in obesity, can promote clinical practice also presents a limitation: markers of sys-

lipotoxicity and insulin resistance, as well as enhancing se- temic inflammation were obtained opportunistically through

cretion of some proinflammatory myokines capable of both in- routine laboratory test results available in the electronic medi-

ducing muscle dysfunction and exacerbating chronic, low- cal record. C-reactive protein level was available for few pa-

grade systemic inflammation.15 tients (<10%) and was therefore not used. However, results

Importantly, low BMI is not sufficient to identify low were largely consistent regardless of the metric of systemic in-

muscle mass in an inflammatory and catabolic disease such flammation examined, as well as across subgroups defined by

as CRC,7 particularly because obesity is common. Among the age, BMI, sex, and stage. As in any observational study, re-

patients with nonmetastatic disease in this study, fewer than sidual confounding is possible; for example, physical activity

5% had a BMI of less than 20, yet 44% had sarcopenia and 46% is not well measured in the electronic medical record and pa-

had a prediagnosis NLR of 3 or greater. These factors may help tients with higher NLR may experience fatigue leading to in-

identify patients with an elevated mortality risk where BMI activity and therefore to compromised muscle mass. Further-

and/or weight change cannot.7,19-21 Using clinically acquired more, socioeconomic status, diet, and alcohol consumption

CT images to aid in the early identification of sarcopenia could were not captured and could plausibly influence NLR, sarco-

facilitate therapeutic intervention to ensure a successful tran- penia, and cancer death.

sition into survivorship. Treatments might include anti-

inflammatory drugs10,11 and/or resistance training, which is

proven to be safe and effective in maintaining and/or increas-

ing muscle mass and function in patients with cancer, im-

Conclusions

proves quality of life, and is associated with longer survival.39-42 Both sarcopenia and high NLR were independent prognostic

This study cannot disentangle the web of bidirectional re- indicators in nonmetastatic CRC. If our findings are con-

lationships among inflammation, body composition, and can- firmed by additional studies, these 2 biomarkers are already

cer progression. Although there was a temporal order to our collected in routine care and thus have high potential for use

data—patients who presented with sarcopenia at diagnosis had in clinical prognostication. We also found that the co-

elevated levels of NLR over the 24 months prior to diagno- occurrence of sarcopenia and inflammation at diagnosis iden-

sis—we cannot determine whether this consistently inflamed tified patients with a more than 2-fold risk of mortality com-

state precipitated sarcopenia or whether these are concur- pared with patients with neither condition; before this

rent conditions. Cancer begins years before diagnosis, yet the information can be used to influence treatment decisions or

appearance of sarcopenia was evaluated once, for the first time, tailor interventions, future research must clarify whether

at diagnosis; thus, we cannot determine how muscle mass reducing systemic inflammation or increasing muscle mass

changes in relation to cancer initiation or the onset of inflam- can enhance progression-free survival and through what

mation. Furthermore, whereas sarcopenia and elevated NLR mechanisms.

E6 JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaoncology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer Original Investigation Research

ARTICLE INFORMATION 2017]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. doi:10 estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional

Accepted for Publication: June 5, 2017. .1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0200 image. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004;97(6):2333-2338.

Published Online: August 10, 2017. 8. Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, et al. 24. Mourtzakis M, Prado CM, Lieffers JR, Reiman T,

doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2319 Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in McCargar LJ, Baracos VE. A practical and precise

solid tumors: a systematic review and approach to quantification of body composition in

Author Contributions: Drs Cespedes Feliciano and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. cancer patients using computed tomography

Caan had full access to all the data in the study and 2014;23(7):1204-1212. images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol

take responsibility for the integrity of the data and Nutr Metab. 2008;33(5):997-1006.

the accuracy of the data analysis. 9. Gu L, Li H, Chen L, et al. Prognostic role of

Study concept and design: Cespedes Feliciano, lymphocyte to monocyte ratio for patients with 25. Prado CM, Birdsell LA, Baracos VE. The

Prado, Kroenke, Alexeeff, Caan. cancer: evidence from a systematic review and emerging role of computerized tomography in

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(22):31926-31942. assessing cancer cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat

authors. 10. Ewaschuk JB, Almasud A, Mazurak VC. Role of Care. 2009;3(4):269-275.

Drafting of the manuscript: Cespedes Feliciano. n-3 fatty acids in muscle loss and myosteatosis. 26. Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, et al. Cancer

Critical revision of the manuscript for important Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(6):654-662. cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle

intellectual content: All authors. 11. Multimodal Intervention for Cachexia in depletion is a powerful prognostic factor,

Statistical analysis: Cespedes Feliciano, Bradshaw, Advanced Cancer Patients Undergoing independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;

Alexeeff, Weltzien. Chemotherapy (MENAC). 2016. https://clinicaltrials 31(12):1539-1547.

Obtained funding: Prado, Caan. .gov/ct2/show/NCT02330926. Accessed 27. Miyamoto Y, Baba Y, Sakamoto Y, et al.

Administrative, technical, or material support: November 10, 2016. Sarcopenia is a negative prognostic factor after

Cespedes Feliciano, Prado, Castillo. curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg

Supervision: Cespedes Feliciano, Prado, Corley, 12. Baracos VE. Cancer-associated cachexia and

underlying biological mechanisms. Annu Rev Nutr. Oncol. 2015;22(8):2663-2668.

Caan.

2006;26:435-461. 28. Haram A, Boland MR, Kelly ME, Bolger JC,

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. Waldron RM, Kerin MJ. The prognostic value of

13. Fearon KC, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC. Cancer

Funding/Support: This work was supported by cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer:

grant R01 CA175011-01 from the National Cancer pathways. Cell Metab. 2012;16(2):153-166. a systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(4):470-

Institute of the National Institutes of Health. 479.

14. Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic 29. Malietzis G, Johns N, Al-Hassi HO, et al. Low

had no role in the design and conduct of the study; review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. muscularity and myosteatosis is related to the host

collection, management, analysis, and 2010;9:69. systemic inflammatory response in patients

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg.

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit 15. Kalinkovich A, Livshits G. Sarcopenic obesity or 2016;263(2):320-325.

the manuscript for publication. obese sarcopenia: a cross talk between

age-associated adipose tissue and skeletal muscle 30. Richards CH, Roxburgh CS, MacMillan MT, et al.

Previous Presentation: An earlier version of this inflammation as a main mechanism of the The relationships between body composition and

analysis was presented as a poster at the American pathogenesis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;35:200-221. the systemic inflammatory response in patients

Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting; with primary operable colorectal cancer. PLoS One.

April 3, 2017; Washington, DC. 16. Durham WJ, Dillon EL, Sheffield-Moore M. 2012;7(8):e41883.

Inflammatory burden and amino acid metabolism in

cancer cachexia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 31. Go SI, Park MJ, Song HN, et al. Sarcopenia and

REFERENCES inflammation are independent predictors of

2009;12(1):72-77.

1. Shachar SS, Williams GR, Muss HB, Nishijima TF. survival in male patients newly diagnosed with

Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid 17. Müller MJ, Baracos V, Bosy-Westphal A, et al. small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24

tumours: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Functional body composition and related aspects in (5):2075-2084.

Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:58-67. research on obesity and cachexia: report on the

12th Stock Conference held on 6 and 7 September 32. Kantola T, Klintrup K, Väyrynen JP, et al.

2. Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, et al. 2013 in Hamburg, Germany. Obes Rev. 2014;15 Stage-dependent alterations of the serum cytokine

Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in (8):640-656. pattern in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012;

solid tumors: a systematic review and 107(10):1729-1736.

meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124. 18. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics,

2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7-30. 33. Baracos VE. Regulation of skeletal-muscle-

3. Joglekar S, Nau PN, Mezhir JJ. The impact of protein turnover in cancer-associated cachexia.

sarcopenia on survival and complications in surgical 19. Kroenke CH, Neugebauer R, Meyerhardt J, et al. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):1015-1018.

oncology: a review of the current literature. J Surg Analysis of body mass index and mortality in

patients with colorectal cancer using causal 34. Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Madrid LV, Wang CY,

Oncol. 2015;112(5):503-509. Baldwin AS Jr. NF-kappaB-induced loss of MyoD

diagrams. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1137-1145.

4. Ali R, Baracos VE, Sawyer MB, et al. Lean body messenger RNA: possible role in muscle decay and

mass as an independent determinant of 20. Meyerhardt JA, Kroenke CH, Prado CM, et al. cachexia. Science. 2000;289(5488):2363-2366.

dose-limiting toxicity and neuropathy in patients Association of weight change after colorectal

cancer diagnosis and outcomes in the Kaiser 35. Hotamisligil GS. The role of TNFalpha and TNF

with colon cancer treated with FOLFOX regimens. receptors in obesity and insulin resistance. J Intern

Cancer Med. 2016;5(4):607-616. Permanente Northern California Population. Cancer

Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(1):30-37. Med. 1999;245(6):621-625.

5. Barret M, Antoun S, Dalban C, et al. Sarcopenia is 36. Wang X, Hu Z, Hu J, Du J, Mitch WE. Insulin

linked to treatment toxicity in patients with 21. Cespedes Feliciano EM, Kroenke CH,

Meyerhardt JA, et al. Metabolic dysfunction, resistance accelerates muscle protein degradation:

metastatic colorectal cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66 activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by

(4):583-589. obesity, and survival among patients with

early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 defects in muscle cell signaling. Endocrinology.

6. Jung HW, Kim JW, Kim JY, et al. Effect of muscle (30):3664-3671. 2006;147(9):4160-4168.

mass on toxicity and survival in patients with colon 37. Srikanthan P, Hevener AL, Karlamangla AS.

cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. 22. Prado CM, Cushen SJ, Orsso CE, Ryan AM.

Sarcopenia and cachexia in the era of obesity: Sarcopenia exacerbates obesity-associated insulin

Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(3):687-694. resistance and dysglycemia: findings from the

clinical and nutritional impact. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;

7. Caan BJ, Meyerhardt JA, Kroenke CH, et al. 75(2):188-198. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Explaining the obesity paradox: the association III. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10805.

between body composition and colorectal cancer 23. Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, et al. Total

body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: 38. Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, et al.

survival (C-SCANS Study) [published online May 15, Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic

jamaoncology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 E7

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

Research Original Investigation Systemic Inflammation, Sarcopenia, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer

obesity in patients with solid tumours of the survivors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 43. Peterson SJ, Mozer M. Differentiating

respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: 2013;45(11):2080-2090. sarcopenia and cachexia among patients with

a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7): 41. Padilha CS, Marinello PC, Galvão DA, et al. cancer. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32(1):30-39.

629-635. Evaluation of resistance training to improve 44. Sakuma K, Aoi W, Yamaguchi A. Molecular

39. Focht BC, Clinton SK, Devor ST, et al. muscular strength and body composition in cancer mechanism of sarcopenia and cachexia: recent

Resistance exercise interventions during and patients undergoing neoadjuvant and adjuvant research advances. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469(5-6):

following cancer treatment: a systematic review. therapy: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(3): 573-591.

J Support Oncol. 2013;11(2):45-60. 339-349.

40. Strasser B, Steindorf K, Wiskemann J, Ulrich 42. Hardee JP, Porter RR, Sui X, et al. The effect of

CM. Impact of resistance training in cancer resistance exercise on all-cause mortality in cancer

survivors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(8):1108-1115.

E8 JAMA Oncology Published online August 10, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaoncology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/ by a UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE LIBRARY User on 08/10/2017

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- NCCN Guideline RC v3 2022Document20 pagesNCCN Guideline RC v3 2022dony hendrawanNo ratings yet

- Bone Tumour Staging - PathologyDocument2 pagesBone Tumour Staging - Pathologyo7113No ratings yet

- Psycho-Oncology - 2018 - Holland - Psycho Oncology Overview Obstacles and OpportunitiesDocument13 pagesPsycho-Oncology - 2018 - Holland - Psycho Oncology Overview Obstacles and OpportunitiesRegina100% (1)

- PSA Testing For Prostate Cancer Information For Well MenDocument2 pagesPSA Testing For Prostate Cancer Information For Well MenkernowsebNo ratings yet

- Intolerância A Lactose Artigo IIDocument8 pagesIntolerância A Lactose Artigo IITícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Different Methods For Diagnostic of Sarcopenia and Its AssociationDocument17 pagesDifferent Methods For Diagnostic of Sarcopenia and Its AssociationTícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Fatores Determinantes Da Sarcopenia em Indivíduos Com Doença de Parkinson - LUZ, Marcella Campos Lima, 2020Document7 pagesFatores Determinantes Da Sarcopenia em Indivíduos Com Doença de Parkinson - LUZ, Marcella Campos Lima, 2020Tícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med-2018-Marino-A031286 - Mieloma Multiplo e OssoDocument22 pagesCold Spring Harb Perspect Med-2018-Marino-A031286 - Mieloma Multiplo e OssoTícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Gait Speed, Grip Strength, and Clinical Outcomes in Older Patients With Hematologic MalignanciesDocument9 pagesGait Speed, Grip Strength, and Clinical Outcomes in Older Patients With Hematologic MalignanciesTícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Biology and Treatment of Myeloma RelatedDocument11 pagesBiology and Treatment of Myeloma RelatedTícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Bard Magnum Manual de UsuarioDocument144 pagesBard Magnum Manual de UsuarioNelson LebronNo ratings yet

- Ef Ficacy and Safety of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy For Pediatric Malignancies: The LITE-SABR Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesEf Ficacy and Safety of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy For Pediatric Malignancies: The LITE-SABR Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisRaul Matute MartinNo ratings yet

- Role of Imaging in OncologyDocument30 pagesRole of Imaging in OncologyAnshul VarshneyNo ratings yet

- 65 - Approach To Patients With CancerDocument1 page65 - Approach To Patients With CancerRica Alyssa PepitoNo ratings yet

- Ref - Medscape - Cervical Cancer Treatment Protocols - Treatment ProtocolsDocument4 pagesRef - Medscape - Cervical Cancer Treatment Protocols - Treatment Protocolsapoteker intanNo ratings yet

- Umang Previous Activities - BriefDocument1 pageUmang Previous Activities - BriefDipesh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Imrt, Igrt, SBRT Advances in The Treatment Planning and Delivery of RadiotherapyDocument1 pageImrt, Igrt, SBRT Advances in The Treatment Planning and Delivery of RadiotherapyPrasanth PNo ratings yet

- Open - Oregonstate.education-Foundations of EpidemiologyDocument11 pagesOpen - Oregonstate.education-Foundations of EpidemiologyAMANE COTTAGE HOSPITALNo ratings yet

- Colorectal Cancer DissertationDocument6 pagesColorectal Cancer DissertationBestPaperWritingServicesSingapore100% (1)

- Uncinate Process First-A Novel Approach For Pancreatic Head Resection - 2010Document4 pagesUncinate Process First-A Novel Approach For Pancreatic Head Resection - 2010Jaldo Santos FreireNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument7 pagesUntitledmandla simelaneNo ratings yet

- 4 5881784375581870090Document6 pages4 5881784375581870090Ahmed noor Ahmed noorNo ratings yet

- Journal of Dermatology ResearchDocument5 pagesJournal of Dermatology ResearchAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Case 3 Reproductive Block PBLDocument16 pagesCase 3 Reproductive Block PBLFarisNo ratings yet

- Sponsorship Proposal For MasterChef Denning EDIT VERSIONDocument2 pagesSponsorship Proposal For MasterChef Denning EDIT VERSIONSimran Pamela ShahaniNo ratings yet

- Inflammatory Breast Cancer A Literature ReviewDocument1 pageInflammatory Breast Cancer A Literature ReviewCarlos AcevedoNo ratings yet

- All Program 240423Document26 pagesAll Program 240423NoneNo ratings yet

- Hydro CatalystDocument3 pagesHydro CatalystKenneth SyNo ratings yet

- Health 6 Quarter 1 Module4Document13 pagesHealth 6 Quarter 1 Module4Cindy EsperanzateNo ratings yet

- Cancer Pain HomeopathyDocument50 pagesCancer Pain HomeopathyKaran PurohitNo ratings yet

- Retraction Retracted: Apoptosis and Molecular Targeting Therapy in CancerDocument24 pagesRetraction Retracted: Apoptosis and Molecular Targeting Therapy in CancerMARIA ANGGIE CANTIKA DEWANINo ratings yet

- Initial Mammography Training Course: 40-48 Category A Credits - 5 or 6 Day Course in The ClassroomDocument2 pagesInitial Mammography Training Course: 40-48 Category A Credits - 5 or 6 Day Course in The Classroomahmed_galal_waly1056No ratings yet

- NCM106 - M11CaseStudy (NU202-Group2)Document3 pagesNCM106 - M11CaseStudy (NU202-Group2)AinaB ManaloNo ratings yet

- Risiko Terjadinya Limfedema Pada Pasien Kanker Payudara Yang Mengalami Infeksi Setelah Menjalani Operasi Terkait Usia Di Rumah Sakit DharmaisDocument7 pagesRisiko Terjadinya Limfedema Pada Pasien Kanker Payudara Yang Mengalami Infeksi Setelah Menjalani Operasi Terkait Usia Di Rumah Sakit DharmaisWawaNo ratings yet

- The Present and Future of Bispecific Antibodies For Cancer TherapyDocument19 pagesThe Present and Future of Bispecific Antibodies For Cancer Therapyvignezh1No ratings yet

- Clinical Considerations Guide - ALLDocument4 pagesClinical Considerations Guide - ALLnenitaNo ratings yet