Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ccorredor Thoma

Uploaded by

numb25Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ccorredor Thoma

Uploaded by

numb25Copyright:

Available Formats

BOOK REVIEWS 311

with both minimalists and contextualists. With contextualists such as Recanati and

Relevance Theorists, they hold that there is a clear dividing line between the explicit

content of an utterance (i.e. ‘enriched what is said’ or ‘explicature’) and its implica-

tures, even if pragmatic reasoning is involved in the derivation of both. However,

K&P also hold that the various minimal propositions expressed by an utterance (viz.

various utterance-bound propositions) may have a role to play in its interpretation, a

position which K&P see as aligning them with authors such as Cappelen and Lepore

(Insensitive semantics: A defense of semantic minimalism and speech act pluralism. Oxford:

Blackwell, 2005) and Borg (Minimal Semantics. Oxford: OUP, 2004). K&P differ from

the semantic minimalists, however, in that they seek to examine how these minimal

propositions are employed by speakers and hearers in the communication of utterance

content. The book ends with an interesting chapter that seeks to tie together the au-

thors’ views on content with their view of utterance interpretation.

Written in a jaunty and engaging style, this book is well suited to those who want a

relatively straightforward introduction to ideas developed in Perry’s Reference and Reflex-

ivity (2001), and K&P’s “Three demonstrations and a funeral” (2006). However, the

book is much more than an introductory text. It is also an argument for a shift in the-

oretical perspective. Despite the influence of Austin and Grice, the figures of Russell

and Frege loom large in contemporary theorising about language. As K&P note (p.

162), these authors were largely concerned with removing ambiguity and nuance from

natural language, so that the pursuit of knowledge could be facilitated by the ability to

make precise, transparent statements. Although not working towards the same end,

much modern pragmatic theorising nevertheless mirrors this project in that it sees the

process of utterance interpretation as being, in no small part, geared towards specify-

ing the precise content of the explicit component of the speaker’s meaning, which

then serves as the basis for the calculation of implicatures (or for the rational recon-

struction of that process). K&P, by contrast, see the identification, by the hearer, of

the speaker’s intentions as being possible without identifying the explicit content of

her utterance. This is a very welcome move, as it encourages us to think about linguis-

tic encoding in different terms: not as a way of directing the hearer to the speaker’s

explicit content, but as a means of directing him towards the implicatures she intends

to communicate, so that he might thereby grasp the intended significance of her utter-

ance.

Mark Jary

University of Roehampton

m.jary@roehampton.ac.uk

DOI: 10.1387/theoria.11404

IAN JARVIE & JESÚS ZAMORA-BONILLA, eds. 2011. The SAGE Handbook of the Philoso-

phy of Social Sciences. London: SAGE Publications.

For the SAGE Handbook of the Philosophy of Social Sciences, editors Ian Jarvie and Jesús

Zamora-Bonilla assembled 39 contributions from some of the leading scholars of the

field. A remarkable number of contributions are from practicing scientists. This is tes-

Theoria 80 (2014): 309-318

312 BOOK REVIEWS

tament to a commitment to keeping philosophy of science close to practice that is also

apparent in most of the individual contributions. However this doesn’t mean that the

Handbook restricts itself to methodological work (which is often contiguous to deba-

tes within the sciences). In fact it distinguishes itself from similar volumes, such as the

2012 Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Social Science (Oxford University Press, edited by

Harold Kincaid) through its emphasis on the history of social science and its philoso-

phy on the one hand, and on the ontological commitments of the social sciences on

the other.

As Jarvie points out in his introduction to the 749-page volume, the philosophy of

social science is “wide-ranging, untidy, interdisciplinary and constantly being reconfi-

gured in response to new problems thrown up by developments in the social sciences”

(p.1). This can make it hard for scholars and students who are new to the field, or new

to some specific area therein, to find their way in. A good handbook can greatly facili-

tate this: its entries will provide accessible and concise statements of the central ques-

tions that arise with regard to a particular topic, the necessary amount of historical ba-

ckground to make sense of a debate, and a well-organised review of the literature most

relevant to the state of the art. Most of the contributions to the SAGE Handbook of the

Philosophy of Social Sciences do a very good job at this, which should make it a great re-

source both for philosophers with an interest in social science, and scientists with an

interest in the philosophical underpinnings of their subjects.

The Handbook is divided into four parts, and an introduction and an epilogue by

the editors. Part 1 is focused on the history of the field, part 2 deals with social onto-

logy, part 3 introduces the paradigms of social science, and part 4 exhibits some of the

most important methodological debates in the social sciences. Part 1 contains only

three articles, which, due to their narrative character, are best appreciated in their enti-

rety. What stands out in this part is David Teira’s wonderfully clear exposition of

‘Continental’ philosophies of science (which he provides after asserting that there is

no such thing as ‘Continental’ philosophy). Though Teira is selective in the material

covered, the entry is a helpful resource to go back to when reading some of the later

articles in the volume, especially the second half of part 3, which covers a number of

social science paradigms commonly classed as ‘Continental’.

Two themes run through the second part of the Handbook, on ‘Central Issues in

Social Ontology’. The first is the question in how far the subject matter of the social

sciences makes it distinct from the natural sciences. For instance, Frank Hindrik’s en-

try on language critically discusses the idea that language plays a central role in the

construction of the social (focusing especially on Searle), which may be seen as setting

the social apart from the natural. Don Ross’ entry on naturalism contains some fasci-

nating explorations of the relation between biology and social science, examining both

the biological and evolutionary roots of sociality, and the idea that the biological is

pervaded with the social.

The second major theme of part 2 is methodological individualism, and the rela-

tion of ‘macro’ and ‘micro’ levels of analysis. In fact, this cluster is relevant to nearly

all the entries in this part, so that a lot of common ground is covered. Nevertheless,

the diversity of viewpoints the reader is thereby offered on this issue is itself fascina-

Theoria 80 (2014): 309-318

BOOK REVIEWS 313

ting and informative. For instance, Ross’ contribution claims that no social science

presupposes individualism, while a number of other articles suggest that insofar as

economics is committed to rational choice theory, it is wedded to methodological in-

dividualism. Alban Bouvier’s piece on individualism and the micro-macro relation

contains a number of useful conceptual clarifications that throw light on such debates.

Part 2 also contains Daniel Little’s compelling and refreshingly political paper on

social class and power in contemporary North America, arguing that these notions

should still be very relevant to social scientific research today. Fred D’Agostino’s entry

on rational agency, and Fabienne Peter and Kai Spiekermann’s entry on ‘Rules, Norms

and Commitments’ are two wonderful examples of what excellent handbook articles

can do: They are accessible and clear in style and in organisation, locate their topics in

the historical and wider philosophical context, throw light on the terminology used in

different strands of the literature, and offer a comprehensive overview of the current

debate. D’Agostino’s article offers a very instructive overview of debates around ra-

tional agency in general philosophy, and then discusses Weber’s work, methodological

individualism, and ‘Homo oeconomicus’. Peter and Spiekermann discuss the questions

of what rules and norms are, what motives people have to act according to them, and

how they emerge (with a special focus on the last, which is a topic that has gained

much recent attention).

While most articles in part 2 are square on the topic of social ontology, the place-

ment of some in this part is more surprising: Andreas Pickel’s entry on ‘Systems

Theory’ claims that systems theory could be considered as “philosophy of (social)

science, paradigm, or heuristic, on the one hand, and [...] substantive explanatory

theory, on the other” (p. 240), which invites the question why this entry is not in

either the part on paradigms, or the part on methodology. As Jarvie acknowledges in

the introduction, causality may be seen both as an important topic in ontology, as well

as one in methodology. But Daniel Steel’s entry on ‘Causality, Causal Models, and So-

cial Mechanisms’ leans heavily on the methodology side: it is mostly concerned with

different methods and models of causal inference. Steel distinguishes between varia-

ble-, case- and mechanism-oriented research, and argues that variable- and case-based

methods, which typically use linear equations and Boolean logic respectively for their

causal models, have a common underlying logic. In particular, both can be represented

as different parameterisations of Bayes nets. Mechanism-oriented research often pro-

ceeds by process-tracing, which, as an indirect form of causal inference, can help

overcome some of the problems of variable- and case-based approaches. Steel thus

expresses a distinct point of view in the literature on causal inference. Furthermore,

using simple examples, he provides some of the most straight-forward introductions

to the various models of causal inference he discusses, including Bayes nets, that I

have seen.

Part 3 of the Handbook aims to provide ‘A Philosopher’s Guide to Social Science

Paradigms’. I must admit that the selection of articles in this part left me unsure of

what a social science paradigm is supposed to be, and the introduction provides little

clarification. Peter Hedström and Petri Ylikoski depict Analytical Sociology as charac-

terised by a shared epistemic goal, namely causal explanation. This is probably closest to

Theoria 80 (2014): 309-318

314 BOOK REVIEWS

what most people intuitively think of as a research paradigm. But this part of the book

starts with entries on rational choice theory, game theory and social choice theory,

which present their subjects either as research tools or theories. Sun-Ki Chai’s article on

‘Theories of Culture, Cognition, and Action’ looks at a number of theories about concepts

that are relevant for the social sciences. Grouping all these entries together under the

heading of ‘paradigms’ is somewhat confusing.

Having said that, this part of the book not only presents the most important

theories/research tools/schools of thought/paradigms that were relevant to social

science in the 20th century, such as structuralism, functionalism, critical theory, prag-

matism and rational choice theory. It also gives equal space to relatively new develop-

ments, such as the study of social networks (Joan de Marti and Yves Zenou). Cédric

Paternotte’s entry on rational choice theory is an excellent introduction to the basics

of mainstream decision theory, and the major criticisms that have been launched

against it, both pertaining to its structure and its application in social science. It also

briefly touches on some of the major recent developments. To those unfamiliar with

rational choice theory, this entry makes excellent prior reading to and connects very

well with many other articles in the Handbook, such as the entries on methodological

individualism, evolutionary approaches and game theory. Giacomo Bonanno’s entry

on game theory is much more technical and focuses on questions of rationality rather

than applications in social science. Bonanno’s article also exhibits a commitment to

the ‘epistemic programme’ in game theory, which, despite its philosophical merits, is

not mainstream amongst economists. Another very helpful article in part 3 is Geoffrey

Hodgson’s entry on evolutionary approaches in the social sciences, which is admirably

sensitive to the ambiguity of the term ‘evolution’, and does a great job at dispelling

myths of evolutionary models importing the ideas of ‘Social Darwinism’ or biologism

into social science.

Part 4, finally, provides a comprehensive and up-to-date picture of methodological

issues in the social sciences. It starts with an article by Heather Douglas, who systema-

tically explores where values enter social scientific research, and how, despite the va-

lue-laden and social aspects of social science, we may still be able to claim objectivity

for it. From this general perspective, we zoom in to more specific aspects of social

scientific methodology, which are all excellently treated, with a wealth of examples

from the social sciences: theoretical models (Tarja Knuuttila and Jaakko Kuorikoski),

the sources and role of evidence (Julian Reiss), laboratory experiments (Francesco

Guala), the use of mathematics and statistics (Stephan Hartmann and Jan Sprenger),

agent-based simulation (Till Grüne-Yanoff), and expert judgement (Maria Jiménez-

Buedo and Jesús Zamora-Bonilla).

Knuuttila and Kuorikoski do a good job at providing an overview of one of the

untidier debates in the philosophy of science. Philosophers have asked many different

questions about models, concerning, for instance, their relation to theories, their role

in scientific representation, the consequences of idealisation in models, and whether

and how we can learn from models. In addition, there is a growing, more applied lite-

rature that focuses on how and for what purposes scientists use models. Knuuttila and

Kuorikoski cover this diverse terrain comprehensively in a very dense discussion.

Theoria 80 (2014): 309-318

BOOK REVIEWS 315

Till Grüne-Yanoff’s entry on agent-based simulation and Jiménez-Buedo and Za-

mora-Bonilla’s entry on expert judgement again show a dedication to giving space to

more recent developments in the philosophy of social science. While Grüne-Yanoff

discusses the novelty of agent-based simulation in social science critically, this very

debate, and the attention philosophers have paid to agent-based simulation, are quite

recent. Discussions of expertise have been around for a while, but till recently have

been conducted in various disjoint branches of philosophy. Drawing together these

strings, and presenting the study of expert judgement as the coherent, independent re-

search project that it is now considered to be, is a special achievement of Jiménez-

Buedo and Zamora-Bonilla’s contribution.

Part 4 also contains entries on explanation and prediction, which are often consi-

dered the two most important goals of science. Jeroen Van Bouwel and Erik Weber’s

clear and well-argued article on explanation focuses on how debates in general philo-

sophy of science may illuminate the philosophy of social science and vice-versa. After

a concise presentation of the standard general theories of explanation, they use these

theories to make sense of debates within the philosophy of social science: So, for ins-

tance, whether there is explanatory virtue in unification is relevant for debates about

the ideal level of explanation (which relates to the debates about the macro-micro rela-

tionship in part 2). At the same time, the variety of explanations and epistemic inter-

ests that are served by these explanations in social science puts into question the ex-

tent to which the ‘winner’ should ‘take it all’ with regard to general theories of expla-

nation. Finally, Gregor Betz’s contribution on prediction is one of the most fascina-

ting in the volume, and contains both a critical discussion of whether and why predic-

tion should be a goal of science, and a sobering review of the longterm performance

of macroeconomic forecasts of GDP and inflation. Of special interest to economic

methodologists should be the observation that there are no significant differences in

predictive performance between the different forecasting methods that are currently

used in macroeconomic forecasting.

Altogether, the Handbook covers an impressively wide range of issues. The few

prominent topics in the philosophy of social science that have not been given separate

entries (such as feminist approaches in social science and its philosophy, or the ques-

tion of whether there are laws in the social realm) can be read up on using the extensi-

ve index. While a large number of articles are excellent in terms of organisation, wri-

ting, clarity and selection of material, the high quality of the contributions in these

respects does not run through the entire volume. And (especially with an eye to the

next edition) it should be noted that all too often, poor copy-editing gets in the way of

readability, as too many articles contain too many mistakes. Still, these deficiencies,

and the problems in the organisation of the volume I mentioned above, should not

distract from the Handbook’s many virtues: its aim is ambitious, and it should serve its

purpose extremely well.

Johanna Thoma

University of Toronto

johanna.thoma@mail.utoronto.ca

DOI: 10.1387/theoria.11406

Theoria 80 (2014): 309-318

You might also like

- Biosemiosis, Technocognition, and Sociogenesis: December 2012Document31 pagesBiosemiosis, Technocognition, and Sociogenesis: December 2012Ardilla BlancaNo ratings yet

- APSSDocument231 pagesAPSSArdilla BlancaNo ratings yet

- Diaz de Rada Angel The Concept of CultureDocument22 pagesDiaz de Rada Angel The Concept of CultureArdilla BlancaNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Philosophical Logic. Vol.10Document353 pagesHandbook of Philosophical Logic. Vol.10Ardilla BlancaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sample 3Document6 pagesSample 3Jhon Jhon OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Defining and Measuring Electronic Commerce.Document15 pagesDefining and Measuring Electronic Commerce.Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- GOV350K2019937555Document4 pagesGOV350K2019937555ashraf shalghoumNo ratings yet

- Action Research Method of Inquiry in Education: PGC 402 Lissy Yu Wang EDUDocument36 pagesAction Research Method of Inquiry in Education: PGC 402 Lissy Yu Wang EDUKatherine ChenNo ratings yet

- Nurwana 2023 (Tjiptono)Document10 pagesNurwana 2023 (Tjiptono)Christopher OswariNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Kajian KesDocument3 pagesTutorial Kajian KesWong Lee KeongNo ratings yet

- Correlation and Regression AnalysisDocument13 pagesCorrelation and Regression AnalysisManoj Mudiraj100% (2)

- SM6611Document2 pagesSM6611PrinceNo ratings yet

- Personalised and Adaptive LearningDocument4 pagesPersonalised and Adaptive LearningShreemoyee BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Lkti Efektifitas Pengenalan Pariwisata Melalui Aplikasi Geoguessr Terhadap Pembangkitan Ekonomi Kreatif Jawa TimurDocument8 pagesLkti Efektifitas Pengenalan Pariwisata Melalui Aplikasi Geoguessr Terhadap Pembangkitan Ekonomi Kreatif Jawa Timurcecilia angelinaNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument20 pagesResearchcassandraolson.kya07No ratings yet

- June 2010: ArticleDocument20 pagesJune 2010: ArticleMohammed Abu shawishNo ratings yet

- D - Anas Bin AriffinDocument15 pagesD - Anas Bin AriffinAiman HaiqalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Action ResearchDocument32 pagesIntroduction To Action ResearchAnglophile123No ratings yet

- Hypothesis TestingDocument30 pagesHypothesis TestingtemedebereNo ratings yet

- Combinepdf PDFDocument620 pagesCombinepdf PDFsophia lizarondoNo ratings yet

- Answers To Exercises and Review Questions: T-TestDocument27 pagesAnswers To Exercises and Review Questions: T-TestAdriano ZanluchiNo ratings yet

- Doctrinal and Non-Doctrinal ResearchDocument13 pagesDoctrinal and Non-Doctrinal ResearchFahim KhanNo ratings yet

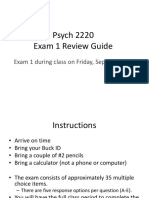

- Psych 2220 Exam 1 Review GuideDocument16 pagesPsych 2220 Exam 1 Review GuideSalil MahajanNo ratings yet

- Article Review ofDocument2 pagesArticle Review ofPutri anjjarwati100% (1)

- Book ReviewDocument11 pagesBook ReviewANGELYN TI-ADNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 1 5Document5 pagesUnit 3 1 5Athul KNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 SummaryDocument9 pagesChapter 5 SummaryMr DamphaNo ratings yet

- Final ThesisDocument41 pagesFinal ThesisseveralchanceNo ratings yet

- Ahmad's ProjectDocument41 pagesAhmad's ProjectToyeeb AbdulyakeenNo ratings yet

- Formulating The Research ProblemDocument20 pagesFormulating The Research ProblemMaris Medida DlsNo ratings yet

- Experimental Psychology ReviewerDocument26 pagesExperimental Psychology ReviewerOkiek Alegna PabilanNo ratings yet

- Analisis Aspek Bias Dalam Pengambilan Keputusan Pembelian Asuransi Jiwa Di IndonesiaDocument24 pagesAnalisis Aspek Bias Dalam Pengambilan Keputusan Pembelian Asuransi Jiwa Di IndonesiaSri NingsihNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Thinking Critically With Psychological Science, Myers 8e PsychologyDocument26 pagesChapter 1 Thinking Critically With Psychological Science, Myers 8e Psychologymrchubs100% (7)

- LAS 3 PR2 Quarter 2 Week 4Document8 pagesLAS 3 PR2 Quarter 2 Week 4Nathaniel TumanguilNo ratings yet