Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Trends and Reported Risk Factors Among.6

National Trends and Reported Risk Factors Among.6

Uploaded by

Karina NathaniaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

National Trends and Reported Risk Factors Among.6

National Trends and Reported Risk Factors Among.6

Uploaded by

Karina NathaniaCopyright:

Available Formats

Infectious Disease: Original Research

National Trends and Reported Risk Factors

Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis in the

United States, 2012–2016

Shivika Trivedi, MD, MSc, Charnetta Williams, MD, Elizabeth Torrone, PhD, and Sarah Kidd, MD, MPH

Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Gamkn0m7hy6RQdEwn41RO+8A2b2lxJ+usZSs/MbJ/W4= on 01/22/2019

OBJECTIVE: To describe recent syphilis trends among ing health care provider awareness of the Centers for

pregnant women and to evaluate the prevalence of Disease Control and Prevention and the American

reported high-risk behaviors in this population. College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommen-

METHODS: We analyzed U.S. national case report data dations, which include screening all pregnant women for

for 2012–2016 to assess trends among pregnant women syphilis at the first prenatal visit and rescreening high-risk

with all stages of syphilis. Risk behavior data collected women during the third trimester and at delivery. Health

through case interviews during routine local health care providers should also consider local syphilis preva-

department investigation of syphilis cases were used to lence in addition to individual reported risk factors when

evaluate the number of pregnant women with syphilis deciding whether to repeat screening.

reporting these behaviors. (Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:27–32)

RESULTS: During 2012–2016, the number of syphilis DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003000

cases among pregnant women increased 61%, from

S

1,561 to 2,508, and this increase was observed across

all races and ethnicities, all women aged 15–45 years, yphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused

and all U.S. regions. Of 15 queried risk factors, including by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Syphilis can

high-risk sexual behaviors and drug use, 49% of pregnant also be spread through mother-to-child transmission

women with syphilis did not report any in the past year. and results in congenital syphilis if untreated in up to

The most commonly reported risk behaviors were a his- 80% of cases.1 Mother-to-child transmission of syphi-

tory of a sexually transmitted disease (43%) and more lis can occur during any trimester of pregnancy and at

than one sex partner in the past year (30%). any stage of syphilis with the highest risk of transmis-

CONCLUSION: Syphilis cases among pregnant women sion during early syphilis (primary, secondary, or

increased from 2012 to 2016, and in half, no traditional early latent stages).1 The sequelae of congenital syph-

behavioral risk factors were reported. Efforts to reduce ilis affect multiple organ systems and can cause pre-

syphilis among pregnant women should involve increas- maturity, stillbirth, and neonatal and infant death.2,3

However, congenital syphilis is preventable with ade-

From the CDC Foundation and the Division of STD Prevention, Centers for

quate and timely screening, diagnosis, and benzathine

Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

penicillin G treatment of maternal syphilis.4,5

Presented as a poster at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’

Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, Austin, Texas, April 27–30, 2018. In the United States, syphilis rates among women

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do and infants have increased dramatically in recent

not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Pre- years. Between 2012 and 2016 the rate of reported

vention. primary and secondary syphilis among women more

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for than doubled (111.1% increase; 0.9–1.9 cases/100,000

authorship.

women) and the congenital syphilis rate increased

Corresponding author: Shivika Trivedi, MD, MSc, 200 Central Park Circle NE, 86.9% (8.4–15.7 cases/100,000 live births).6 Given

Atlanta, GA 30312; email: Shivikatrivedi@gmail.com.

the preventable nature of congenital syphilis, several

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. studies have examined possible missed opportunities

© 2018 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Published

and highlighted the importance of early and adequate

by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. prenatal care, timely identification of pregnant

ISSN: 0029-7844/19 women with syphilis, and, if infected, timely receipt

VOL. 133, NO. 1, JANUARY 2019 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY 27

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

of a stage-appropriate penicillin regimen at least 30 Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Native

days before delivery (Introcaso CE, Bradley H, Grub- American or Alaska Native, and non-Hispanic white),

er D, Markowitz LE. Missed opportunities for pre- and U.S. regions were defined using the U.S. Census

venting congenital syphilis infection [letter]. Sex geographic regions (Midwest, North, South, or

Transm Dis 2013;40:431.).7–12 West).6,17 In addition to demographic data, information

The timely identification of pregnant women with about risk behaviors is collected for cases that are in-

syphilis requires universal screening at the first pre- terviewed or investigated by the local public health

natal care appointment and possible repeat screening department. To evaluate the prevalence of reported

in the third trimester for certain populations. For the risk factors among pregnant women with syphilis, we

latter, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention focused on high-risk sexual behaviors (prior STD;

and the American College of Obstetricians and greater than one sex partner; sex while intoxicated;

Gynecologists recommend repeat syphilis screening anonymous sex partner; sex for drugs or money; sex

in the third trimester and at delivery for pregnant with persons known to inject drugs; sex with gay, bisex-

women who are at high risk for syphilis or who live in ual, or other men who have sex with men), drug-related

areas with high syphilis morbidity.5 risk factors, history of incarceration, and human immu-

Many studies have demonstrated increased rates nodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The timing of each

of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in those who of these risk factors referred to the 12 months before

have a partner in a high-risk sexual network or who the diagnosis of syphilis except for evaluation of prior

themselves have a history of incarceration or sub- STD, which asked about one’s lifetime risk and HIV

stance abuse.13–16 However, it is unclear what propor- status, documented through test result, record search,

tion of pregnant women with syphilis report risk or self-reported at the time of syphilis diagnosis.

factors and which risk factors are most common Most risk factor variables were collected and

among pregnant women with syphilis. To better reported with values of “yes,” “no,” “missing,” or

understand pregnant women with syphilis, we ana- “unknown.” However, in some jurisdictions, variables

lyzed national case report data to describe recent on specific drug use (ie, crack, cocaine, heroin, meth-

trends in syphilis among pregnant women and evalu- amphetamine, “other drug use,” and “no drug use”)

ated the prevalence and trends of reported risk behav- were collected in a “check all that apply” format,

iors in this population. where the absence of a “yes” response indicates

a “no” response, but were reported to the CDC as

METHODS “yes,” “no,” “missing,” or “unknown.” Thus, a re-

Data on all reported female syphilis cases (any stage) ported value of “missing” or “unknown” could indi-

were extracted from the National Notifiable Diseases cate either a “no” response for each of the specific

Surveillance System, which provides the CDC with drugs listed or be truly missing or unknown. To

data about notifiable sexually transmitted infections account for the “check all apply” format for these

from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The specific variables, if a case was reported without data

syphilis case reports are received as deidentified, line- for the specific drug (eg, crack) and also responded

listed data that include demographic information, “yes” to either the variable “no drug use” or one of the

stage of syphilis (primary, secondary, early latent, or other specific drug variables (eg, methamphetamine),

late latent cases), and other variables such as preg- this case was counted as a “no” response for the spe-

nancy status if ascertained. Additional data on demo- cific drug (crack). The proportion of cases reporting

graphics, self-reported risk behaviors and information each risk factor was calculated using a denominator

about sexual partners in the past 12 months, and self- made up of those with a yes or no response for that

reported lifetime history of previous STDs are col- risk factor. When calculating the proportion of preg-

lected by local health department staff and included in nant women with syphilis reporting any risk factor,

this system. Data on prenatal care, treatment, and the total number of pregnant women with syphilis

pregnancy outcomes are not included in these reports. from 2012 to 2016 was used as the denominator.

In this study, we analyzed the case reports for all We also applied this same method to focus

pregnant women with any stage of syphilis, from all 50 specifically on pregnant females with early syphilis,

states and the District of Columbia, from 2012 to 2016 because this group is at higher risk for congenital

by maternal characteristics, including age, race and syphilis and may represent a higher risk population.

Hispanic ethnicity, and census region. Race and When calculating the proportion of pregnant women

Hispanic ethnicity were defined using National Center with early syphilis reporting any risk factor, the total

for Health Statistics bridged-race categories (Asian or number of pregnant women with primary and

28 Trivedi et al Trends Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

secondary or early latent syphilis from 2012 to 2016 Overall, most (59%) pregnant women with syph-

was used as the denominator. ilis were in their 20s and the greatest number of cases

Trends in the proportion of cases reporting each was consistently among non-Hispanic blacks, averag-

risk factor were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage ing 49% of reported syphilis cases among pregnant

trend test; a two-sided P value ,.05 was considered women per year. Most (56%) pregnant women with

statistically significant. All data were analyzed using syphilis were from the South (Table 1). Reported

SAS 9.4. This study used data that are routinely col- cases of syphilis among pregnant women increased

lected as a part of public health surveillance for the in those aged 15–45 years, in every race and ethnicity

purpose of guiding public health disease control ef- group, and in every region during 2012–2016. By age,

forts and was therefore not subject to institutional the greatest increase in cases was seen in women aged

review board approval for human subjects’ protection. 30–34 years (90%). By race and ethnicity, the greatest

increase in cases was among Native Americans or

RESULTS Alaskan Natives (420%). By region, the greatest

During 2012–2016, the number of reported cases of increase was seen in the West (292%) followed by

syphilis among females increased 55%, from 9,551 to the North (44%), the Midwest (35%), and the South

14,838, and the number of cases among pregnant (29%).

women increased 61%, from 1,561 to 2,508 (Fig. 1). Combining data from 2012 to 2016, the overall

The percentage of reported female syphilis cases prevalence of any reported risk factor was 51%

known to be pregnant was relatively stable during this (4,997/9,883) (Table 2). Stated differently, 49% of

time period, ranging from 16% to 18% of all reported pregnant women with syphilis did not report having

female syphilis cases. The percentage of female syph- any high-risk behaviors. The most commonly re-

ilis cases with “missing” or “unknown” pregnancy sta- ported risk behaviors, in pregnant women with any

tus decreased from 27% in 2012 to 20% in 2016. stage of syphilis, were prior STD (43%) and more than

During 2012–2016, the increase in early syphilis one sex partner in the past 12 months (30%). When

cases (primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis) the analysis was restricted to pregnant women with

among pregnant women exceeded the increase in late early syphilis, representing women with a recent infec-

latent syphilis cases so that the proportion of pregnant tion, the overall prevalence of any reported risk factor

syphilis cases that were late latent decreased from 65% was slightly higher at 63% (2,434/3,850) (Table 3).

to 42% over the same time period (P,.001) (Fig. 1). These women reported the same risk behaviors most

Early syphilis cases among pregnant women increased commonly, but again in higher proportions, with 50%

52% from 553 cases in 2012 to 1,065 cases in 2016. reporting a prior STD and 38% reporting more than

Late latent syphilis cases among pregnant women one sex partner. Of the specific drugs surveyed, the

increased 43%, from 1,008 to 1,443 cases. highest overall prevalence was for methamphetamine

use in pregnant women with all stages (4.5%) and in

pregnant women with early syphilis (6.3%).

For trends in reported risk behaviors over time,

the proportion of pregnant women, with any stage of

syphilis, reporting a prior STD increased (P,.001) as

did the proportion of women reporting having sex

with a known injection drug user (P,.001) and the

proportion reporting having sex with a partner known

to be a man who has sex with men (P5.0076)

(Table 2). The proportion of pregnant women with

syphilis reporting crack, cocaine, or heroin use in

the past 12 months decreased or remained stable over

time as did the proportion reporting having sex in

exchange for drugs or money. The proportion report-

ing injection drug use was stable. Of the drugs sur-

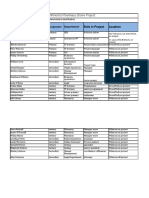

Fig. 1. Reported cases of early and late latent syphilis

among pregnant women. The increase in the proportion of veyed, the largest increase was in methamphetamine

cases that were early syphilis cases was statistically signif- use reported by pregnant women with syphilis. From

icant (P,.001). 2012 to 2016, the proportion reporting methamphet-

Trivedi. Trends Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis. Obstet amine use more than doubled from 2.2% to 7.1%

Gynecol 2019. (P,.001).

VOL. 133, NO. 1, JANUARY 2019 Trivedi et al Trends Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis 29

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Pregnant Women With Reported Syphilis Cases (All Stages),

2012–2016*

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2012–2016*

Demographic (n51,561) (n51,633) (n51,955) (n52,226) (n52,508) (n59,883)

Age (y)

Younger than 15 1 (0.1) 5 (0.3) 6 (0.3) 3 (0.1) 1 (0.04) 16 (0.2)

15–19 227 (14.5) 212 (13.0) 253 (12.9) 235 (10.6) 307 (12.2) 1,234 (12.5)

20–24 522 (33.4) 560 (34.3) 626 (32.0) 748 (33.6) 772 (30.8) 3,228 (32.7)

25–29 378 (24.2) 375 (23.0) 524 (26.8) 594 (26.7) 689 (27.5) 2,560 (25.9)

30–34 238 (15.3) 268 (16.4) 326 (16.7) 396 (17.8) 451 (18.0) 1,679 (17.0)

35–39 140 (9.0) 166 (10.2) 165 (8.4) 188 (8.5) 212 (8.5) 871 (8.8)

40–44 44 (2.8) 43 (2.6) 53 (2.7) 54 (2.4) 66 (2.6) 260 (2.6)

Older than 45 11 (0.7) 3 (0.2) 2 (0.1) 8 (0.4) 9 (0.4) 33 (0.3)

Race and Hispanic ethnicity

Native American or Alaskan 5 (0.3) 12 (0.8) 15 (0.8) 15 (0.7) 26 (1.1) 73 (0.7)

Native

Asian or Pacific Islander 47 (3.2) 59 (3.8) 63 (3.5) 93 (4.5) 78 (3.3) 340 (3.4)

Hispanic 394 (26.4) 460 (29.7) 555 (30.4) 625 (30.0) 755 (31.8) 2,789 (28.2)

Non-Hispanic black 833 (55.8) 781 (50.5) 876 (48.0) 946 (45.4) 1,070 (45.0) 4,506 (45.6)

Non-Hispanic white 215 (14.4) 236 (15.3) 316 (17.3) 405 (19.4) 448 (18.9) 1,620 (16.4)

Region

Midwest 235 (15.1) 203 (12.4) 234 (12.0) 294 (13.2) 316 (12.6) 1,282 (13.0)

Northeast 187 (12.0) 195 (11.9) 234 (12.0) 228 (10.2) 270 (10.8) 1,114 (11.3)

South 965 (61.8) 969 (59.3) 1,132 (57.9) 1,212 (54.5) 1,240 (49.4) 5,518 (55.8)

West 174 (11.2) 266 (16.3) 355 (18.2) 492 (22.1) 682 (27.2) 1,969 (19.9)

Data are n (%).

* Column totals may not add up to total number of cases or 100% because of cases reported with missing or unknown data.

DISCUSSION Although identification of risk behaviors may

Syphilis cases among pregnant women increased only detect less than half of the pregnant women with

among all demographic groups from 2012 to 2016. syphilis, women who do report risk factors, particu-

Of these cases, the proportion that was early syphilis larly drug use, likely require special attention and

also rose, which is concerning because these represent additional efforts to prevent congenital syphilis.

more recent infections with higher titers and a greater Socioeconomic factors and risk behaviors such as

risk of mother-to-child transmission. Our data dem- drug use are intimately related and both have been

shown to affect the uptake of prenatal care, which in

onstrate that screening relying solely on behavioral

turn affects timely syphilis screening and treat-

risk factors would miss approximately half of preg-

ment.18,19 Moreover, even when these women are

nant women with any stage of syphilis and approxi-

adequately screened and offered treatment, they likely

mately one third of pregnant women with recently

remain at a higher risk for being lost to follow-up, for

acquired syphilis.

not receiving adequate treatment, and for having rein-

These findings support current recommendations

fection after treatment.

for universal syphilis screening at the first prenatal visit

These data and this analysis have limitations. As

and indicate that it may be necessary to include a result of the lack of current data on the number of

population context when determining whether to pregnancies in the United States, we were unable to

implement repeat screening during pregnancy. The calculate syphilis rates per 100,000 pregnant women.

CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Therefore, trend data or comparisons between demo-

Gynecologists both recommend repeat screening graphic groups might be affected by changes in the

between 28 0/7 weeks and 32 0/7 weeks of estimated pregnancy rates over time or differences in pregnancy

gestation and again at delivery for pregnant women in rates in different demographic groups. We considered

communities and populations with a high prevalence of using the number of live births per year to calculate

syphilis.5 Health departments, particularly in areas with a ratio of pregnant women with syphilis per 1,000 live

a high burden of female syphilis, should ensure that births. However, given that pregnancies complicated

health care providers are aware of local syphilis prev- by maternal syphilis can result in miscarriage or

alence and regulations for prenatal syphilis screening. stillbirth, these cases would not have been included

30 Trivedi et al Trends Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 2. Reported Risk Factors Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis (All Stages), 2012–2016

Reported Risk 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2012–2016*†

Factor* (n51,561) (n51,633) (n51,955) (n52,226) (n52,508) (n59,883)

Prior STDठ452/1,135 (39.8) 512/1,196 (42.8) 581/1,410 (41.2) 673/1,544 (43.6) 831/1,740 (47.8) 3,049/7,025 (43.4)

More than 1 sex 387/1,258 (30.8) 421/1,301 (32.4) 457/1,570 (29.1) 495/1,784 (27.8) 656/2,063 (31.8) 2,416/7,976 (30.3)

partner

Sex while 177/1,165 (15.2) 178/1,200 (14.8) 212/1,455 (14.6) 272/1,629 (16.7) 301/1,873 (16.1) 1,140/7,322 (15.6)

intoxicated

Anonymous sex 98/1,152 (8.5) 94/1,187 (7.9) 117/1,466 (8.0) 157/1,622 (9.7) 177/1,873 (9.5) 643/7,300 (8.7)

partner

Incarceration 87/1,157 (7.5) 86/1,198 (7.2) 104/1,463 (7.1) 114/1,627 (7.0) 171/1,865 (9.2) 562/7,310 (7.7)

Sex for drugs or 49/1,173 (4.2) 48/1,213 (4.0) 52/1,460 (3.6) 62/1,651 (3.8) 61/1,907 (3.2) 272/7,404 (3.7)

money

Sex with persons 21/1,122 (1.9) 32/1,149 (2.8) 35/1,394 (2.5) 65/1,575 (4.1) 79/1,771 (4.5) 232/7,011 (3.3)

known to inject

drugs§

HIV-positive‡ 13/1,071 (1.2) 18/1,080 (1.7) 13/1,330 (1.0) 26/1,420 (1.8) 31/1,877 (1.7) 101/6,788 (1.5)

Sex with MSMk 11/1,106 (1.0) 11/1,121 (1.0) 11/1,344 (0.8) 19/1,539 (1.2) 35/1,727 (2.0) 87/6,837 (1.3)

Methamphetamine 24/1,081 (2.2) 22/1,147 (1.9) 47/1,411 (3.3) 94/1,523 (6.2) 129/1,827 (7.1) 316/6,986 (4.5)

usek

Cocaine use 30/1,083 (2.8) 22/1,147 (1.9) 41/1,409 (2.9) 37/1,524 (2.4) 43/1,812 (2.4) 173/6,975 (2.5)

Crack use 25/1,083 (2.3) 14/1,146 (1.2) 21/1,408 (1.5) 18/1,522 (1.2) 25/1,809 (1.4) 103/6,968 (1.5)

Heroin use 17/1,082 (1.6) 18/1,146 (1.6) 18/1,407 (1.3) 30/1,524 (2.0) 26/1,816 (1.4) 109/6,975 (1.6)

Injection drug use 24/1,136 (2.1) 29/1,155 (2.5) 27/1,434 (1.9) 51/1,567 (3.3) 50/1,733 (2.9) 181/7,025 (2.6)

Nitrates or poppers 2/1,066 (0.2) 1/1,144 (0.1) 4/1,406 (0.3) 6/1,519 (0.4) 7/1,772 (0.4) 20/6,907 (0.3)

use

Other drug use 115/1,080 (10.7) 138/1,146 (12.0) 198/1,407 (14.1) 198/1,531 (12.9) 226/1,826 (12.4) 875/6,990 (12.5)

Any risk factor§k 747/1,561 (47.9) 828/1,633 (50.7) 987/1,955 (50.5) 1,095/2,226 (49.2) 1,340/2,508 (53.4) 4,997/9,883 (50.6)

STD, sexually transmitted disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Data are n/N (%).

* Timing of risk factors referred to the last 12 months before diagnosis of syphilis except: prior STD (lifetime risk); HIV-positive (documented

or self-reported at the time of syphilis diagnosis).

†

Values are a sum of data from 2012 to 2016. Denominators vary because number missing or unknown (excluded) varies by risk factor.

‡

Timing of risk factors referred to the last 12 months before diagnosis of syphilis except: prior STD (lifetime risk); HIV-positive (documented

or self-reported at the time of syphilis diagnosis).

§

Change in proportion was statistically significant (P,.05).

k

Combines all risk factors.

in the denominator of live births. The sample we ported risk factors among pregnant women. Analysis

described included any pregnant woman with syphi- of reported behavioral risk data is also limited given

lis, regardless of pregnancy outcome. Moreover, the these data are collected in an interview format and the

number of live births from 2012 to 2016 was relatively completion of the report form is performed at the

stable and did not fluctuate more than 1.5% over this interpretation and discretion of a local health officer.

time period.20 In addition, STD surveillance data Moreover, the personal nature of some of the behav-

have inherent limitations. Case-based surveillance ioral questions, along with a fear of legal repercussions

data likely underestimate the true number of syphilitic including the possible loss of custody of children, may

infections among pregnant women in the country as also contribute to underreporting of risk factors.

a result of underascertainment and underreporting of Finally, our data did not include information about

syphilitic infections and pregnancy status. For pregnancy outcome, and we were unable to link preg-

instance, if all women with syphilis with unknown nant syphilis cases to reported congenital syphilis

pregnancy status were pregnant, the estimated num- cases. Thus, we were not able to examine whether

ber of pregnant women with syphilis in 2016 would be certain risk behaviors were associated with congenital

more than double our estimate (from 2,508 to 5,523); syphilis or adverse pregnancy outcomes.

however, it is unlikely that all or most women with Despite these limitations, this study adds to the

unknown pregnancy status were truly pregnant. It is limited information on national trends in demo-

possible that women with unknown pregnancy status graphic data and reported behavioral risk factor data

are more likely to have risk factors, so exclusion from among pregnant women with syphilis. Through an

our analysis could underestimate prevalence of re- increased awareness of the rising syphilis cases among

VOL. 133, NO. 1, JANUARY 2019 Trivedi et al Trends Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis 31

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 3. Reported Risk Factors Among Pregnant 5. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and

Women With Early Syphilis, 2012–2016 Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines,

2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64:1–137.

(n53,850)

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmit-

† ted disease surveillance 2016. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of

Reported Risk Factor* n/N* (%) Health and Human Services; 2017.

Prior STD‡ 1,524/3,021 (50.4) 7. Biswas HH, Chew Ng RA, Murray EL, Chow JM, Stoltey JE,

Greater than 1 sex partner 1,317/3,436 (38.3) Watt JP, et al. Characteristics associated with delivery of an

Sex while intoxicated 628/3,215 (19.5) infant with congenital syphilis and missed opportunities for

prevention—California, 2012–2014. Sex Transm Dis 2018;

Anonymous sex partner 337/3,193 (10.6)

45:435–41.

Incarceration 304/3,212 (9.5)

Sex for drugs or money 154/3,245 (4.7) 8. Matthias JM, Rahman MM, Newman DR, Peterman TA. Effec-

Sex with persons known to inject drugs 132/3,047 (4.3) tiveness of prenatal screening and treatment to prevent congen-

ital syphilis, Louisiana and Florida, 2013–2014. Sex Transm Dis

HIV-positive‡ 53/2,863 (1.9)

2017;44:498–502.

Sex with MSM 61/2,933 (2.1)

Methamphetamine use 192/3,052 (6.3) 9. Kidd S, Bowen VB, Torrone EA, Bolan G. Use of national syphilis

Cocaine use 81/3,043 (2.7) surveillance data to develop a congenital syphilis prevention cas-

Crack use 47/3,038 (1.5) cade and estimate the number of potential congenital syphilis cases

averted. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45(suppl 1):S23–8.

Heroin use 63/3,044 (2.1)

Injection drug use 101/3,050 (3.3) 10. Patel SJ, Klinger EJ, O’Toole D, Schillinger JA. Missed oppor-

Nitrates or poppers use 13/3,010 (0.4) tunities for preventing congenital syphilis infection in New

Other drug use 481/3,053 (15.8) York City. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:882–8.

Any risk factor§ 2,434/3,850 (63.2) 11. Taylor MM, Mickey T, Browne K, Kenney K, England B,

Blasini-Alcivar L. Opportunities for the prevention of congen-

STD, sexually transmitted disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency ital syphilis in Maricopa County, Arizona. Sex Transm Dis

virus; MSM, men who have sex with men. 2008;35:341–3.

* Timing of risk factors referred to the last 12 months before

diagnosis of syphilis except: prior STD (lifetime risk); HIV- 12. Warner L, Rochat RW, Fichtner RR, Stoll BJ, Nathan L, Too-

positive (documented or self-reported at the time of syphilis mey KE. Missed opportunities for congenital syphilis preven-

diagnosis). tion in an urban southeastern hospital. Sex Transm Dis 2001;

† 28:92–8.

Values are a sum of data from 2012 to 2016. Denominators vary

because number missing or unknown (excluded) varies by risk 13. Healthy People 2020. Sexually transmitted diseases—social, eco-

factor. nomic, and behavioral factors. Available at: https://www.

‡

Timing of risk factors referred to the last 12 months before healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/sexually-trans-

diagnosis of syphilis except: prior STD (lifetime risk); HIV- mitted-diseases. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

positive (documented or self-reported at the time of syphilis

diagnosis). 14. Marx R, Aral SO, Rolfs RT, Sterk CE, Kahn JG. Crack, sex,

§

Combines all risk factors. and STD. Sex Transm Dis 1991;18:92–101.

15. Eng TR, Butler WT, editors. The hidden epidemic: confronting

pregnant women as well as these trend data, health sexually transmitted diseases: summary. Washington, DC:

care providers can be better informed to ensure they National Academies Press; 1997.

are following national guidelines and state policies for 16. Kirkcaldy RD, Su JR, Taylor MM, Koumans E, Mickey T,

Winscott M, et al. Epidemiology of syphilis among Hispanic

syphilis screening in pregnancy. Lastly, we hope that women and associations with congenital syphilis, Maricopa

these data and the continued collection of surveillance County, Arizona. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:598–602.

data, including risk factors, may help guide the 17. National Vital Statistics System. United States census 2000 pop-

evolution of future public health interventions so they ulation with bridged race categories. In: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics.

are tailored to the socioeconomic factors and behav- Hyattsville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Serv-

iors of this population. ices; 2003.

18. Funkhouser AW, Butz AM, Feng TI, McCaul ME, Rosenstein

REFERENCES BJ. Prenatal care and drug use in pregnant women. Drug Alco-

hol Depend 1993;33:1–9.

1. Ingraham NR Jr. The value of penicillin alone in the preven-

tion and treatment of congenital syphilis. Acta Derm Venereol 19. Maupin R Jr, Lyman R, Fatsis J, Prystowiski E, Nguyen A,

Suppl (Stockh) 1950;31(suppl 24):60–87. Wright C, et al. Characteristics of women who deliver with

no prenatal care. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2004;16:45–50.

2. Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, Mark J, Broutet N,

Hawkes SJ. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes 20. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake

of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull P. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2018;67:1–55.

World Health Organ 2013;91:217–26.

3. Cooper JM, Sánchez PJ. Congenital syphilis. Semin Perinatol

2018;42:176–84. PEER REVIEW HISTORY

4. Alexander JM, Sheffield JS, Sanchez PJ, Mayfield J, Wendel Received July 30, 2018. Received in revised form September 20,

GD Jr. Efficacy of treatment for syphilis in pregnancy. Obstet 2018. Accepted September 27, 2018. Peer reviews and author cor-

Gynecol 1999;93:5–8. respondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B210.

32 Trivedi et al Trends Among Pregnant Women With Syphilis OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- Pregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsFrom EverandPregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsNo ratings yet

- Accounting I ModuleDocument92 pagesAccounting I ModuleJay Githuku100% (1)

- DPP 1-7 Gravitation JA Nurture LiveDocument44 pagesDPP 1-7 Gravitation JA Nurture LiveTejaswi JhaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology in A Nutshell NCI BenchmarksDocument8 pagesEpidemiology in A Nutshell NCI BenchmarksThe Nutrition CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Project Stakeholder register-DroneTechDocument4 pagesProject Stakeholder register-DroneTechfrank100% (2)

- Health Belief Model On The Determinants of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination in Women of Reproductive Age in Surakarta, Central JavaDocument11 pagesHealth Belief Model On The Determinants of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination in Women of Reproductive Age in Surakarta, Central Javaadilla kusumaNo ratings yet

- Day 33 Practice TestsDocument16 pagesDay 33 Practice TestsTUYẾN KIMTUYẾN0% (6)

- Syphilis in Pregnancy: Clinical Expert SeriesDocument15 pagesSyphilis in Pregnancy: Clinical Expert SeriesWindy MuldianiNo ratings yet

- Syphilis in PregnancyDocument17 pagesSyphilis in PregnancyKevin Stanley HalimNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Risk Factors in Antenatal Women at Ishaka Adventist Hospital, UgandaDocument9 pagesAssessment of Risk Factors in Antenatal Women at Ishaka Adventist Hospital, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- SphilisDocument17 pagesSphilisKharisma AstiNo ratings yet

- BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019Document8 pagesBMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019cdsaludNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer - An Overview of Pathophysiology and ManagementDocument9 pagesCervical Cancer - An Overview of Pathophysiology and ManagementIndah 15No ratings yet

- Prevalence and Determinants of Anemia in Pregnancy, Sana'a, YemenDocument8 pagesPrevalence and Determinants of Anemia in Pregnancy, Sana'a, YemenIJPHSNo ratings yet

- 17 Listeriosis in PregnancyA ReviewDocument7 pages17 Listeriosis in PregnancyA ReviewRaul A UrbinaNo ratings yet

- Abel Man 2020Document6 pagesAbel Man 2020Redouane idrissiNo ratings yet

- Ped Infect Disease Jr. 2023Document4 pagesPed Infect Disease Jr. 2023cdsaludNo ratings yet

- Hiv Sul InglesDocument7 pagesHiv Sul Inglesandrea azevedoNo ratings yet

- Seminars in Oncology NursingDocument9 pagesSeminars in Oncology NursingangelitostorresitosNo ratings yet

- Costa de Macedo, 2017 - Risk Factors For Syphilis in WomenDocument12 pagesCosta de Macedo, 2017 - Risk Factors For Syphilis in WomenRima Carolina Bahsas ZakyNo ratings yet

- Syphilis During Pregnancy A Preventable Threat To Maternal-Fetal Health.Document12 pagesSyphilis During Pregnancy A Preventable Threat To Maternal-Fetal Health.Andrés Felipe Jaramillo TorresNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Mandatory HIV Testing During Pregnancy in Areas With High HIV Prevalence Rates: Ethical and Policy IssuesDocument5 pagesRethinking Mandatory HIV Testing During Pregnancy in Areas With High HIV Prevalence Rates: Ethical and Policy IssuesChristie ChungNo ratings yet

- E20201433 FullDocument15 pagesE20201433 FullcdsaludNo ratings yet

- Eff Ectiveness of Interventions To Improve Screening For Syphilis in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument8 pagesEff Ectiveness of Interventions To Improve Screening For Syphilis in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisRocky.84No ratings yet

- Fonc 14 1386167Document6 pagesFonc 14 1386167epidemiojsmhNo ratings yet

- Original Article Vaginal Discharge: Perceptions and Health Seeking Behavior Among Nepalese WomenDocument5 pagesOriginal Article Vaginal Discharge: Perceptions and Health Seeking Behavior Among Nepalese WomennovywardanaNo ratings yet

- Predicting Adherence To Antiretroviral Therapy Among Pregnant Women in Guyana: Utility of The Health Belief ModelDocument10 pagesPredicting Adherence To Antiretroviral Therapy Among Pregnant Women in Guyana: Utility of The Health Belief ModelRiska Resty WasitaNo ratings yet

- Management of Newly Diagnosed HIV InfectionDocument16 pagesManagement of Newly Diagnosed HIV InfectionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Contraception Counseling and Use Among AdolescentDocument6 pagesContraception Counseling and Use Among AdolescentAbdulrahman Al-otaibiNo ratings yet

- HIV and Pregnancy: How To Manage Conflicting Recommendations From Evidence-Based GuidelinesDocument6 pagesHIV and Pregnancy: How To Manage Conflicting Recommendations From Evidence-Based GuidelinesIsmaelJoséGonzálezGuzmánNo ratings yet

- Inborn Errors of Metabolism - Feb2011Document54 pagesInborn Errors of Metabolism - Feb2011Manuel Alvarado100% (1)

- Journal Pone 0253373Document17 pagesJournal Pone 0253373ElormNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Research 1Document9 pagesCervical Cancer Research 1tivaNo ratings yet

- Recommendations For Human Immunodeficiency Virus Screening, Prophylaxis, and Treatment For Pregnant Women in The United StatesDocument14 pagesRecommendations For Human Immunodeficiency Virus Screening, Prophylaxis, and Treatment For Pregnant Women in The United StateselaNo ratings yet

- SOFA ObstetricoDocument14 pagesSOFA ObstetricoKarla DominguezNo ratings yet

- Maternal & Perinatal Outcome of Fever in Pregnancy in The Context of DengueDocument5 pagesMaternal & Perinatal Outcome of Fever in Pregnancy in The Context of DengueLola del carmen RojasNo ratings yet

- 43 FullDocument9 pages43 Fullnayeta levi syahdanaNo ratings yet

- HPV ObsosDocument5 pagesHPV ObsosRyan SadonoNo ratings yet

- Efecto de Hiv1 en Mujeres Embarazadas de RwandaDocument8 pagesEfecto de Hiv1 en Mujeres Embarazadas de RwandaIsmaelJoséGonzálezGuzmánNo ratings yet

- Syphilis in PregnancyDocument38 pagesSyphilis in PregnancydrirrazabalNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 394 - Articles - 168216 - Submission - Proof - 168216 4693 432812 1 10 20180314Document6 pagesAjol File Journals - 394 - Articles - 168216 - Submission - Proof - 168216 4693 432812 1 10 20180314God'stime OgeNo ratings yet

- PresusDocument6 pagesPresusFrishia DidaNo ratings yet

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis - Prevalence and Analysis of Associated Risk Factors Among Women of Reproductive Age Group in Vindhya RegionDocument8 pagesVulvovaginal Candidiasis - Prevalence and Analysis of Associated Risk Factors Among Women of Reproductive Age Group in Vindhya RegionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- The Burden of HIV Infection Among Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in A Semi-Urban Nigerian TownDocument6 pagesThe Burden of HIV Infection Among Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in A Semi-Urban Nigerian TownDavid MorgNo ratings yet

- Syphilis in Pregnancy - UpToDateDocument33 pagesSyphilis in Pregnancy - UpToDateGiuliana FloresNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Cervical Cancer: Results From A Hospital-Based Case-Control StudyDocument7 pagesRisk Factors For Cervical Cancer: Results From A Hospital-Based Case-Control StudyIntania RosatiNo ratings yet

- Acute Pyelonephritis in Pregnancy: An 18-Year Retrospective AnalysisDocument6 pagesAcute Pyelonephritis in Pregnancy: An 18-Year Retrospective AnalysisIntan Wahyu CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Awareness, Screening and Vaccination Among Female Nursing Students of University of GhanaDocument7 pagesCervical Cancer Awareness, Screening and Vaccination Among Female Nursing Students of University of GhanaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Management of Vaginal Discharge Syndrome: How Effective Is Our Strategy?Document4 pagesManagement of Vaginal Discharge Syndrome: How Effective Is Our Strategy?Epi PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- Piis258953702200061x PDFDocument11 pagesPiis258953702200061x PDFRong LiuNo ratings yet

- 1 Infants HIV ArticleDocument14 pages1 Infants HIV ArticleSarah MoffattNo ratings yet

- HIV Retesting of HIV-Negative Pregnant Women in The Context of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Primary Health Centers in Rural Zambia: What Did We Learn?Document6 pagesHIV Retesting of HIV-Negative Pregnant Women in The Context of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Primary Health Centers in Rural Zambia: What Did We Learn?nabilahbilqisNo ratings yet

- 718-1519-1-SM 2Document6 pages718-1519-1-SM 2NicoleNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer Awareness Among Health ProfessionalsDocument3 pagesBreast Cancer Awareness Among Health ProfessionalsWac GunarathnaNo ratings yet

- Cervical CA Proposal Jan152010Document21 pagesCervical CA Proposal Jan152010redblade_88100% (2)

- Nursing Open - 2022 - Mukosha - Knowledge Attitude and Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women Living WithDocument10 pagesNursing Open - 2022 - Mukosha - Knowledge Attitude and Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women Living Withluwi mwanguNo ratings yet

- Predictores Tempranos Del Síndrome de Guillain-Barré en El Curso de La Vida de Las MujeresDocument9 pagesPredictores Tempranos Del Síndrome de Guillain-Barré en El Curso de La Vida de Las Mujeresfrancisco bacaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Interventions in Reducing The Rate of Infection After Cesarean DeliveryDocument6 pagesEffect of Interventions in Reducing The Rate of Infection After Cesarean DeliveryEdwin mudumiNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Infections and Clinical Characteristics of Maternal Sepsis: A Hospital Based Retrospective Cohort StudyDocument12 pagesObstetric Infections and Clinical Characteristics of Maternal Sepsis: A Hospital Based Retrospective Cohort StudyblanquishemNo ratings yet

- Bronquiolite Amam.Document13 pagesBronquiolite Amam.gabibarbozaNo ratings yet

- Gynecologic Cancer Types Causes and Therapeutic ApproachesDocument4 pagesGynecologic Cancer Types Causes and Therapeutic ApproachesVuong Xuan Hong QuangNo ratings yet

- Routine Screening in A California Jail: Effect of Local Policy On Identification of Syphilis in A High-Incidence Area, 2016-2017Document8 pagesRoutine Screening in A California Jail: Effect of Local Policy On Identification of Syphilis in A High-Incidence Area, 2016-2017Siti Mediana ShakilaNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Sepsis in S Asia - A Huge Burden and Spiralling AMRDocument5 pagesNeonatal Sepsis in S Asia - A Huge Burden and Spiralling AMRdrdrNo ratings yet

- Vaccines 08 00124 PDFDocument21 pagesVaccines 08 00124 PDFSaúl Alberto Kohan BocNo ratings yet

- YogaDocument13 pagesYogaKarina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Trauma and Aging-Related Genitourinary Dysfunction in A National Sample of Older WomenDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Trauma and Aging-Related Genitourinary Dysfunction in A National Sample of Older WomenKarina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Influenza and Pregnancy No Time For Complacency.5Document4 pagesInfluenza and Pregnancy No Time For Complacency.5Karina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Five Year Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety of A.11Document8 pagesFive Year Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety of A.11Karina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Correlation Between Body Mass Index and Intraocular Pressure at Eye Clinic Mangusada Hospital, BaliDocument3 pagesCorrelation Between Body Mass Index and Intraocular Pressure at Eye Clinic Mangusada Hospital, BaliKarina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Diagnostic Performance of A Novel Noninvasive Workup in The Setting of Dry Eye DiseaseDocument6 pagesResearch Article: Diagnostic Performance of A Novel Noninvasive Workup in The Setting of Dry Eye DiseaseKarina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Retinal Structural and Microvascular Alterations in Different Acute Ischemic Stroke SubtypesDocument10 pagesResearch Article: Retinal Structural and Microvascular Alterations in Different Acute Ischemic Stroke SubtypesKarina NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Heat Treatment Training ManualDocument118 pagesHeat Treatment Training ManualPravin VisputeNo ratings yet

- Bergeron - Process 12345Document3 pagesBergeron - Process 12345SOUTH HINDI DOUBBED NEW MOVIESNo ratings yet

- 3D Numerical Modeling of A Landslide in SwitzerlandDocument6 pages3D Numerical Modeling of A Landslide in Switzerlandadela2012No ratings yet

- DAA ProfileDocument50 pagesDAA ProfileFarixxa AszNo ratings yet

- A Brief Study On Market Sructure and Demand Analysis of Hindustan Unilever LimitedDocument65 pagesA Brief Study On Market Sructure and Demand Analysis of Hindustan Unilever LimitedShivangi AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan MiraDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Miraika pratamaNo ratings yet

- A Step by Step Guide To Creating A Media StrategyDocument8 pagesA Step by Step Guide To Creating A Media StrategyAaron LifordNo ratings yet

- 03 - Baritone Saxophone (E Flat) - UntitledDocument3 pages03 - Baritone Saxophone (E Flat) - UntitledFuNo ratings yet

- What Is Hologram Technology?Document4 pagesWhat Is Hologram Technology?Fathi Elrahman AgilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - Work Measurements and StandardsDocument72 pagesChapter 10 - Work Measurements and StandardsTGTrindadeNo ratings yet

- A Study On Applications of Wavelets To Data MiningDocument11 pagesA Study On Applications of Wavelets To Data MiningAziz Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Essay - DluceDocument3 pagesSynthesis Essay - Dluceapi-550300197No ratings yet

- Fringe Finds Focus - Developments and Strategies in Aboriginal Writing in En... - EBSCOhostDocument11 pagesFringe Finds Focus - Developments and Strategies in Aboriginal Writing in En... - EBSCOhostKarima AssaslaNo ratings yet

- Gunn-The and The Individual: Ross ScientistDocument7 pagesGunn-The and The Individual: Ross ScientistDoor URNo ratings yet

- ClassVI - EPA SummaryDocument14 pagesClassVI - EPA SummarySakshi SinghNo ratings yet

- Topographic Map of Higgins SouthDocument1 pageTopographic Map of Higgins SouthHistoricalMapsNo ratings yet

- Meeting 1: A Past Time To RememberDocument12 pagesMeeting 1: A Past Time To RememberAmyunJun CottonNo ratings yet

- TMobile Call Center PlansDocument16 pagesTMobile Call Center PlansNews10NBCNo ratings yet

- Palm Oil-External Analysis, Competitive & Strategic Group MapDocument4 pagesPalm Oil-External Analysis, Competitive & Strategic Group Mapfaatin880% (1)

- Java Technology Concept MapDocument1 pageJava Technology Concept Mapkostas.karis100% (2)

- Segno Ceramics Glaze Line G.VT Extension LayoutDocument1 pageSegno Ceramics Glaze Line G.VT Extension LayoutNarsing Ramesh BabuNo ratings yet

- Sep 1314-1990Document1 pageSep 1314-1990amit gajbhiyeNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Pension FundDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Pension Funddhjiiorif100% (1)

- Java Crud CodeDocument26 pagesJava Crud CodeleinadmofficialNo ratings yet

- HP Care Services Definitions: GuideDocument2 pagesHP Care Services Definitions: Guideamxrpm1570No ratings yet

- ASTM B179-11 Standard Specification For Aluminum Alloys IngotsDocument12 pagesASTM B179-11 Standard Specification For Aluminum Alloys IngotsDemian LópezNo ratings yet