Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brand Anthropomorphism

Uploaded by

Tanu GuptaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brand Anthropomorphism

Uploaded by

Tanu GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wrong: The Detrimental Effect of Brand

Anthropomorphization Amid Product Wrongdoings

Author(s): Marina Puzakova, Hyokjin Kwak and Joseph F. Rocereto

Source: Journal of Marketing , May 2013, Vol. 77, No. 3 (May 2013), pp. 81-100

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of American Marketing Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23487435

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23487435?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Marketing Association and Sage Publications, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Marketing

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Marina Puzakova, Hyokjin Kwak, & Joseph F. Rocereto

When Humanizing Brands Goes

Wrong: The Detrimental Effect of

Brand Anthropomorphization Amid

Product Wrongdoings

The brand relationship literature shows that the humanizing of brands and products generates more favorable

consumer attitudes and thus enhances brand performance. However, the authors propose negative downstream

consequences of brand humanization; that is, the anthropomorphization of a brand can negatively affect

consumers' brand evaluations when the brand faces negative publicity caused by product wrongdoings. They find

that consumers who believe in personality stability (i.e., entity theorists) view anthropomorphized brands that

undergo negative publicity less favorably than nonanthropomorphized brands. In contrast, consumers who

advocate personality malleability (i.e., incremental theorists) are less likely to devalue an anthropomorphized brand

from a single instance of negative publicity. Finally, the authors explore three firm response strategies (i.e., denial,

apology, and compensation) that can affect the evaluations of anthropomorphized brands for consumers with

different implicit theory perspectives. They find that entity theorists have more difficulty in combating the adverse

effects of brand anthropomorphization than incremental theorists. Furthermore, they demonstrate that

compensation (vs. denial or apology) is the only effective response among entity theorists.

Keywords: brand anthropomorphization, implicit theory, negative publicity, product wrongdoings, response strategies

phism as a positioning strategy for their brands. In baere, McQuarrie, and Phillips 2011).

Marketing

general, practitioners frequently

this marketing communication use anthropomor-

technique However, anthropomorphization

the awareness of intentions triggers the per (Aggarwal and McGill 2007; Del

creates favorable consumer reactions, such as increased ception of intentional action, as well as responsibility for

product likability, enhanced positive emotions, and more this action (Waytz, Gray, et al. 2010). As such, an anthropo

favorable attributions of brand personality (Delbaere, morphic positioning of a brand can have negative repercus

McQuarrie, and Phillips 2011). Such anthropomorphic rep- sions if the brand is perceived as responsible for its wrong

resentations trigger consumers' perceptions of brands as liv- doings. Given the potential negative repercussions of brand

ing entities with their own humanlike motivations, charac- anthropomorphization in these instances, it is critical to

teristics, conscious will, emotions, and intentions (Epley understand whether humanizing a brand can backfire when

and Waytz 2009; Kim and McGill 2011). Overall, prior product failure occurs and which factors may facilitate or

research has largely focused on the positive sides of brand inhibit these negative sides of brand anthropomorphization.

In the marketplace, brands positioned with anthropomor

phic features can receive negative publicity caused by their

Marina Puzakova is Assistant Professor of Marketing, College of Business, product wrongdoings. For example, in 2006, M&M

Oregon State University (e-mail: marina.puzakova@bus.oregonstate. hranded men0rahs were recalled because of a notential fire

edu). Hyokjin Kwak is Associate Professor of Marketing, LeBow College branded menorahs were recalled because ot a potential tire

of Business, Drexel University (e-mail: hkwak@drexel.edu). Joseph F. hazard. Later, m 2008, M&M s received additional negative

Rocereto is Assistant Professor of Marketing, Leon Hess Business publicity when traces of melamine, a poisonous substance,

School, Monmouth University (e-mail: jroceret@monmouth.edu).This arti- were found in M&M candies. Do consumers respond to

cle is based on the first author's doctoral dissertation, which was the run- negative publicity of product wrongdoings less favorably

ner-up for the 2012 Mary Kay Doctoral Dissertation Competition award by when a brand is humanized9

the Academy of Marketing Science. The authors are grateful to the three failures ^ pervasive. For example, according

anonymous JM reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive . , t „ „ j , „ . , . . . ®

suggestions. Many thanks go to Rolph E. Anderson (Drexel University), t0 the U,S- Fo° and g Administration, the number of

Trina Larsen Andras (Drexel University), and Charles R. Taylor (Villanova product recalls in 2011 increased nearly 14% compared

University) for their invaluable input during the various stages of the devel- with that in 2010, from 2,081 to 2,363 (Doering 2012).

opment of this article. In particular, the authors are grateful to Ji Kyung However, academic research is silent as to whether such

Park (University of Delaware) for her enormous effort and time directed product wrongdoings are more harmful to the image of

toward the methodological portion of this article. Barbara Kahn served as anthropomorphized brands. With this research, we attempt

area editor for this article. to m ^ gap ¡n ±t in ^ ways First> we

© 2013, American Marketing Association Journal of Marketing

ISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic) 81 Volume 77 (May 2013), 81-100

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

demonstrate that negative publicity caused by product ing on the application of certain social beliefs (i.e., implicit

wrongdoings has a more detrimental impact on consumers' theories of personality) to humanized brands (Experiments

brand impressions when the brand is humanized than when 2a, 2b, and 3). Third, our conceptualization of the moderat

it is not. The theoretical premise is that consumers perceive ing impact of implicit theories enables us to theoretically

brands endowed with human features as being mindful and and managerially explore which firm response strategies

possessing intentions. People have a fundamental tendency marketers can use to reduce the adverse effects of negative

to attribute others' behaviors to stable traits rather than to publicity for anthropomorphized brands (Experiment 3).

unstable contextual influences (Gawronski 2004); therefore,

consumers may attribute product wrongdoings to stable » . ■■ ... .

traits of humanized brands and consider them responsible. AnthrO

The extent to which people perceive an entity as responsi- AntnrO

ble for an action directly drives their willingness to punish Anthropomorphism invo

this entity for its negative behavior (Epley and Waytz effortful thinking, emot

2009). Thus, if consumers view anthropomorphized brands to nonhuman objects

as performing actions intentionally, their evaluations of the Waytz, and Cacioppo 200

brands' wrongdoings should be more negative than those of theorizes the facto

nonhumanized brands. anthropomorphize nonhuman entities (Epley, Waytz, and

Second, we demonstrate that, when a brand is anthropo- Cacioppo 2007; Waytz, Morewedge, et al.

morphized, the adverse effects of negative publicity depend tors include cognitive aspects, such as the ac

on a significant consumer-based factor—namely, implicit human knowledge at the moment of judgm

theory of personality—which determines the extent to 2008), and motivations, such as the need

which people attribute behaviors to stable traits rather than environment and satisfy belongingne

to contextual factors (Levy, Stroessner, and Dweck 1998; Morewedge, et al. 2010). Research, howe

Molden, Plaks, and Dweck 2006). That is, we show that investigating how anthropomorphization

consumers who believe in the stability of personality traits changes in attitudes and shifts in beliefs. The

(i.e., entity theorists) are more likely to devalue a brand that changes occur mainly for three reasons. Fir

performs negatively when the brand is anthropomorphized. phizing nonhuman entities leads to the attrib

This is because entity theorists consider a single wrongdoing fulness to these entities, which renders the

a manifestation of an underlying negative trait and a reli- agents who have their own conscious goa

able indicator of ongoing future transgressions. Conversely, (Epley and Waytz 2009). For example, the res

consumers who view personality traits as more malleable computer-generated agent to a human evo

(i.e., incremental theorists) do not form impressions based ceptions of intelligence, trustworthiness

on a single transgression and do not deem a single misbe- ness of this agent (Nass, Isbister, and Le

havior a predictor of a future pattern of action. Thus, they the attribution of mindfulness in nonhuman

are less likely to modify their evaluations of an anthropo- people to perceive them as capable of ex

morphized brand's product wrongdoings. tions and to grant them moral value (Waytz, G

Third, an understanding of the consumer side of the 2010). For example, Gray, Gray, and Wegn

negative effect of brand anthropomorphization leads us to that greater attributions of mindfulness to no

explore the firm side. We provide initial exploratory evi- ties correlate with liking for the entity an

dence of the role of firms' strategic responses to the adverse tect it and make it happy. Finally, anthropo

effects of a humanized brand's product wrongdoing. To human agents drives people to perceive th

make this incremental contribution, we theorize and test forming impressions and being able to

three strategic firm responses: denial, apology, and compen- (Epley and Waytz 2009). For example, a

sation. The differences between entity and incremental the- puter agent increases people's beliefs th

orists in their perceptions of the stability of a negative brand scrutinized and leads them to respond in a

performance suggest that not all firm response strategies are desirable manner (Waytz, Gray, et al. 2010)

equally effective in managing consumers' negative évalua- Researchers have further conceptualiz

tions of humanized brands' product wrongdoings (Chen, nisms underlying the effects of anthro

Ganesan, and Liu 2009; Dawar and Pilluda 2000; Dutta and evaluations. In particular, the extent of th

Pullig 2011). human schémas (i.e., cognitive knowledge about an

In summary, five experiments provide important theo- attribute formed on the basis

retical and managerial contributions to the brand anthropo- human features of a nonhuman en

morphism and negative publicity literature. First, to our of the entity (Aggarwal and Mc

knowledge, this research is the first to demonstrate the thought to occur due to (1) a greater s

negative downstream consequences of humanizing a brand from the perceived congruity betwee

when consumers are exposed to negative brand perfor- activated human schémas and (2

manee caused by product wrongdoings (Experiments la affect from a human schema to

and lb). Second, this research enriches the theoretical and McGill 2007). Furthermore, the

understanding of anthropomorphism by providing insights product (e.g., the shape of a bottle)

into how the effect of anthropomorphism can differ depend- by personal pronouns, or mention

82 / Journal of Marketing, May 2013

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

(vs. third) person all affect brand liking (Aggarwal and with high social power because they tend to perceive it as

McGill 2007; Landwehr, McGill, and Herrmann 2011). less risky and thus expose themselves to more risk. How

Along the same lines, when people are exposed to personi- ever, our research is conceptually different from this work

fication metaphors—that is, images that portray a product on the negative role of brand anthropomorphism; we derive

involved in human behavior—they access their human our underpinnings of the negative aspects of brand anthro

schemas to comprehend the images (Delbaere, McQuarrie, pomorphization from an external factor that is not inherent

and Phillips 2011). In turn, they experience perceptual flu- to brand humanization per se—that is, negative publicity,

ency (i.e., the ease of processing humanized stimuli), result- For example, Aggarwal and McGill (2007) investigate the

ing in greater product liking. effects of different types of brand humanization (e.g., good

twins humanization, evil twins humanization) on product

evaluations, whereas the current research investigates the

Brand Anthropomorphization on effects of neutral brand humanization on the processing of

Product Wrongdoings negative publicity.

We propose that the anthropomorphization of a branded Factors that augment consumers' perceptions o

product activates human schémas. Furthermore, this brand's intentionality should affect their brand evaluation

process occurs spontaneously. The activated knowledge of Thus, if humanizing a brand leads to perceptions of th

human schémas connects with a brand's representations brand as more responsible for its actions, negative publici

through associative networks and affects what people think caused by product wrongdoing is likely to lead to le

of a brand. For example, repetitive exposure to a branded favorable consumer evaluations when a brand is anthrop

product infused with features morphologically similar to a morphized than when it is not anthropomorphized,

human (e.g., the humanlike shape of the Mrs. Butterworth's

bottle of syrup) consistently activates human schémas and, H>: ?e.gative ^rand ¡nfonnation caused by a product wrong

.i. ,iL t i fL L j . . , r doing results in less favorable attitudes toward an anthro

through the network of human-brand associations, transfers pomorphized brand than

to an anthropomorphic impression of a brand.

The anthropomorphization of agents leads consumers to

perceive them as capable of having reasoned thoughts and Exp6

intentional actions. The intentional nature of an action cre

We conducted two experiments to explore Hj. Experi

ates the perception that an entity is responsible for its

la investigates an existing brand in the health supplem

actions and thus deserves punishment for wrongdoings

product category, Airborne. This brand recently exper

(Gray, Gray, and Wegner 2007). This tendency is explained

a backlash of negative publicity on the validity of its

by the notion that intentional agents behave according to

benefit claims. In Experiment lb, we replicate our fin

thoughtful underlying reasons that are under their control

with a fictitious brand of an orange juice beverage, O

(Caruso, Waytz, and Epley 2010). Such sensitivity to inten Vie.

tional actions also explains why people get angry with

mindless technological devices when they perceive them Participants, Design, and Procedure

as "intentionally performing" such behaviors (Waytz,

Morewedge et al 2010) In exchange for extra credit, 39 (40) undergraduate students

Prior research has established that a brand's wrongdoings enrolled in marketing courses at a private East Coast un

determined to be intentional are perceived more negatively versity participated in Experiment la (Experiment lb). At

than actions categorized as accidental (Folkes 1984; Klein beginning of Experiment la, participants received a

and Dawar 2004). That is, consumers may perceive the questionnaire and were asked to indicate their level of

locus of responsibility for a failure as internal and brand familiarity with the brand and prior attitude toward the

related or external and context related (Laufer and Gillespie brand. Next, they were exposed to an Airborne advertise

2004). For example, Klein and Dawar (2004) demonstrate ment. At the beginning of Experiment lb, participants

that consumers lowered their brand evaluations when they immediately viewed an advertisement for a product and then

blamed the firm for a product failure. Similarly, Monga and were exPosed t0 negative information about the brand pre

John (2008) show that when consumers attributed Mercedes- sented in a report from consumerist.com (see Web Appen

Benz's manufacturing problems to contextual rather than d'x W1 at www.marketingpower.com/jm_webappendix).

brand-related factors, their attitudes toward the brand Next, participants were asked to provide their evaluations

increased. In essence, attributions of responsibility to a °f Airborne (Orange Vie). Finally, participants answered

brand negatively affect consumers' evaluations of that several questions to ensure that the manipulations held and

bran(j then completed a brief demographic questionnaire section.

Recent work in marketing has documented adverse After both experiments, participants w

downstream effects of anthropomorphism. For example, suspicion probe. None of the particip

Aggarwal and McGill (2007) posit that anthropomorphiza- nature of the research question.

tion of a product based on a primed human schema may

Anthropomorphism Manipulation and Pretest

generate either worse or better product evaluations, depend

ing on the valence of the schema. Furthermore, Kim and We developed two color print adv

McGill (2011) argue that anthropomorphizing an entity that experiment. In Experiment la, th

bears risk might have negative repercussions for consumers brand advertisement depicted the

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wrong 18

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

legs and arms, and the ad copy was written in the first per- same items as in the pretest; aExp la = .91, otExp lb = .93).

son (e.g., "I am Airborne. My focus is to support your We then measured trust in the brand (rExp la = .91,/? < .05;

immune system.") The nonanthropomorphized brand adver- rExp lb = .96, p < .05) on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 =

tisement contained a package of the brand without human- "strongly disagree," and 7 = "strongly agree") with two

like limbs, and the copy was in the third person. In Experi- items (i.e., dependable and reliable). Participants also rated

ment lb, we achieved brand anthropomorphization by the extent to which they perceived the information in the

creating a brand with humanlike behavior. For the stimuli in article as negative (1 = "strongly disagree," and 7 =

Experiment lb, we constructed two advertisements, each "strongly agree"). We assessed involvement with the infor

portraying an image of a bottle of orange juice in a beach mation with two items (i.e., 1 = "very uninvolved, paid very

setting. Specifically, in the anthropomorphized brand condi- little attention," and 7 = "very involved, paid a lot of atten

tion, the bottle was depicted as sitting on a beach chair and tion"; rExp la = .73,p < .05; rExp lb = .86,p < .05).

wearing a human hat (Figure 1). The nonanthropomor

phized brand advertisement presented the same bottle on a Results

table next to a beach chair. Manipulation checks. One-sample t-tests revealed that

In a pretest (nExp la = 26, nExp lb = 44), participants saw consumers perceived the article as providing negative infor

the advertisements and then responded to a two-item mea- ma[10n (M u = 5.97. t(38)diff from 4 = 8.45, p < .05;

sure on the degree to which the Airborne (Orange Vie) M ib = 5 95; t(39)diff from 4 = 9.35, p < .05). Participants'

brand had a mind of its own and its own beliefs and desires invoïvement did not differ statistically across ad types for

(e.g., 1 = "not at all appear to have mind of its own," and 7 = both experiments (ps > ,10). Finally, in Experiment la, all

"definitely appears to have a mind of its own" [Waytz, participants indicated that they were not familiar with the

Morewedge, et al. 2010]; rExp la - .85, p < .05; rExp lb - negative news they had read in the report about the Air

.45, p < .05). Participants in the anthropomorphized brand borne brand

condition perceived Airborne (Orange Vie) as having more

of a mind of its own and its own beliefs than those in the Hypothesis test. In Experiment la, we entered familiar

nonanthropomorphized brand condition (Airborne: Manth = ity with and prior attitude toward the Airborne brand in the

4.71, Mnonanth = 3.71; F(l, 24) = 4.37,p < .05; Orange Vie: data analysis as covariates. However, their effects were

Manth = 4.29, Mnonanth = 3.30; F(l, 41) = 5.71,p < .05). To insignificant, and thus, we dropped them from further

rule out the alternative explanation that the humanized analysis. As H] predicted, the results of both Experiments

advertisement might lead to greater brand liking, we col- la and lb revealed that participants had less favorable atti

lected an additional measure of brand attitude (four items tudes toward and less trust in the anthropomorphized (vs.

on a seven-point scale; 1 = "unfavorable, bad, unpleasant, nonanthropomorphized) brand after exposure to the nega

dislike," and 7 = "favorable, good, pleasant, like"; aExp la = live consumerist.com report. In a multivariate analysis of

•91, aExp. ib = .94). The results of the pretest showed that no variance, with attitude toward and trust in the Airborne

significant differences in brand attitudes emerged across the (Orange Vie) brand as the dependent variable, the effect of

two types of advertisements for both experiments (p > .10). anthropomorphization was significant (Wilks's A,Exp la = .84,

F(2, 36) = 3.41, p < .05; Wilks's kExp. Ib = .83, F(2, 37) =

Measures 3.90, p < .05). That is, brand anthropomorphization led to

We asked participants to indicate their attitudes toward and less favorable attitudes towar

trust in the Airborne (Orange Vie) brand (measured with the 3.04, MExp la nonanth = 3.84; F(1,

FIGURE 1

Manipulations of Anthropomorphized Versus Nonanthropomorphized Brands: Experiment 1b

Nonanthropomorphized Anthropomorphized

841 Journal of Marketing, May 2013

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ib anth = 2.48, MExp lb nonanth = 3.35; F(l, 38) = 5.65, p < theory view (Dweck, Chiu, and Hong 1995; Levy, Chiu,

.05) and less trust in the brand (MExp la anth = 2.52, MExp la and Hong 2006). For example, Hong et al. (1999) find that

nonanth = 3.39; F(l, 37) = 6.07,p < .05; MExp lb anth = 2.15, increased exposure to mass media images that emphasize

MExp lb nonanth = 3.00; F(l, 38) = 6.16, p < .05). individual differences between citizens of Hong Kong and

mainland China during the political turnover in 1997

Discussion resulted in more people becoming entity theorists.

Experiments la and lb consistently demonstrate that the In general, people rely on implicit theories to e

marketing tactics of brand anthropomorphization combined interpret, and predict human behavior (Dweck and Mo

with negative publicity on these brands harmfully affect 2008). Implicit theories affect the way people (1)

consumers' brand attitudes and trust. As such, the negative sonality trait information to make inferences ab

effect of brand humanization differs from the positive role causes of behaviors (Dweck, Chiu, and Hong 1995; Hon

of anthropomorphism documented in previous research. al. 2004) and (2) form judgments of others from a p

Although in general, brand humanization boosts con- instance of behavior (Plaks, Levy, and Dweck 2009).

sumers' brand liking and familiarity, it also increases con- researchers suggest that entity theorists believe

sumers' perceptions of intentionality of a brand's negative behavior observed in a certain situation is a reliab

actions. Moreover, in our experiments, the negative effect tor a corresponding personality trait (Chiu, Hon

of brand anthropomorphization on consumers' processing Dweck 1997). In contrast, incremental theorists foc

of negative publicity held when we manipulated anthropo- on contextual information because they believe th

morphism with both a direct ascription of human features to change and cannot be relied on when making judgme

a package (i.e., humanlike limbs), coupled with a brand's <Dweck and Molden 2008kIn essence' Molden> Plak

message written in first person, and a more subtle represen- Dweck (200b)establish that after initially categorizing

tation of a humanlike behavior (i.e., sitting on a beach chair W* of behavior is Performed, incremental theorists f

and wearing a hat) characterize behaviors in terms of the person's situati

demands, whereas entity theorists explicate behaviors in

terms of the person's traits. Second, additional streams of

The Role of Implicit Theory of research stress that entity theorists expect behaviors

Personality consistent over time and across situations, because peop

.»i ,. , ... . i . . actions are stable manifestations of their underlying traits

Attributing humanlike mental states to an anthropomor- . . , J ,fc

, . , , , , . , ., . . ,. f (Ross and Nisbett 1991). That is, entity theorists make more

phized brand prompts consumers to apply their beliefs _. ... ' . .... , , ,

confident predictions of the stability of an acto

about the social world when judging them. For example,

based on a single act (Chiu, Hong, and Dwec

social psychology researchers have found that people who

... ... , ..... , . contrast, incremental theorists require more examples of

attribute humanlike mental capabilities to nonhuman enti- . , , . , t .

, , . . , , behavior to render a robust judgment of a person (Plaks et

ties are likely to grant these entities moral worth and value. , ,. . ., , . , ,, . .. .. ,

„ , „ , JTTr r. , , , al. 2001). That is, they do not hold static conceptions of

For example, Epley and Waytz.(2009) find that people were le and do not e ec{ a beh

more hesitant to destroy IBM s legendary computer, Big (Levy and Dweck 1999)

Blue when they perceived it as mindfuL in marketing, Kim In ^ wit

and McGill (2011) demonstrate that consumers apply their ¡ncreases ^ {endency tQ a

feelings of social power only when an object (e.g., a slot anthropomorphized agent, w

machine) is anthropomorphized but not when the device different theories of personal

lacks humanlike features. In this research, we examine performance of an anthropom

whether consumers attributions of responsibility to the morphized brand in different

anthropomorphized brand confronting negative media cov- orists are likely t0 view a

erage are qualified by the application of implicit theories of anthropomorphized brand as an

personality that is, lay beliefs about the malleability of brand characteristics. They

traits and attributes related to the self and the environment single wrongdoing a stable and

(Poon and Koehler 2008; Skowronski 2002). As we men- which they can rely to make p

tioned previously, entity theorists believe that personality tjve brand performance. T

traits are fixed and expect a high degree of consistency in sumers perceive an anthro

behavior, whereas incremental theorists believe that person- responsible for its negativ

ality is malleable and view behavior as varying, either over reliable and stable manifestation

time or across situations (Dweck, Chiu, and Hong 1995). tics, entity theorists are likel

Prior research has suggested that these implicit theories tudes toward an anthropomo

develop as a result of socialization practices (e.g., parental morphized brand. In contrast

feedback), accumulated personal experiences that highlight focus on trait information

trait versus situational forces, and everyday contextual cues behaviors after being ex

(Dweck, Chiu, and Hong 1995; Poon and Koehler 2008). (Dweck, Chiu, and Hong 1995;

However, implicit theories can be activated by use of they are likely to view a bran

changes in real-life occurrences, exposure to persuasive unstable and temporal. Thus

arguments, or media evidence that advocates a particular anthropomorphized brand as

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wron

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

not likely to rely on a single, negative act to form an overall reach significance for attitudes toward the brand (measured

judgment of the brand and, as a result, are not likely to with the same items as in Experiments la and lb; a = .91;

judge its wrongdoing more negatively than that of a nonan- Manth = 4.44, Mnonanth = 4.64; p >.10) or for perceptions of

thropomorphized brand. Here, note that we do not expect ad believability (measured on a seven-point scale with three

implicit theory to affect the way consumers view a nonan- items: "not at all believable/highly believable," "unconvinc

thropomorphized brand's negative performance. This is due ing/convincing," and "untrustworthy/trustworthy"; a = .90;

to our theoretical assumption that consumers are likely to Manth = 4.56, Mnonanth = 4.55; p > .10). Negative information

apply their implicit theory views only to anthropomor- about the SuperAct brand appeared in a consumerist.com

phized brands. This assumption is driven by prior research report (see Web Appendix W2 at www.marketingpower.com/

that demonstrates that consumers apply beliefs about the jm_webappendix).

social world to nonhuman entities (e.g., slot machines, dis

ease, brands) only when these entities are anthropomor Implicit Theory Manipulation

phized. For example, Aggarwal and McGill (2012) find no Following prior research (Chiu, Hong, and Dweck 1997;

effect of brand priming on behavior when a brand is repre- Park and John 2010), we induced implicit theories of per

sented as an object. However, they find that consumers sonality by having participants read an article that presented

behave in a manner consistent with a brand's image when views that corresponded with either incremental or entity

they view it in human terms. theory. This is consistent with the idea that implicit theories

IT „ . r . ,, can be situationally activated by exposure to persuasive evi

H2: For entity theorists, negative brand information caused by , , . -i f . r

a product wrongdoing results in less favorable attitudes dence (Hong> Lev7> and Chlu 2001)-

toward an anthropomorphized brand than a nonanthropo- c'e' participants were told that the

morphized brand. In contrast, for incremental theorists, to understand how people compreh

negative brand information caused by a product wrongdoing relevant information. In addition,

results in no differences in attitudes toward either an cate the three most important sente

anthropomorphized or a nonanthropomorphized brand. supported the authors' viewpoint (Pa

entity article informed participants that scientists, th

program of rigorous research, had concluded that

Experiment 2a possess a finite number of traits that do not chang

Participants, Design, and Procedure time-In contrast, the article aiming to

_ , , , , , , • tal theory view stated that scientific research revealed that

One hundred three undergraduate students at a private East nalit traits are d a

Coast university participated in Experiment 2a. As a cover research findi were c

story, participants were told that they would take part in two |es and cas

unrelated studies that were grouped together for efficiency. ^

The first study contained an implicit theory manipulation.

In the second study, participants were asked to form an (Entity theory)

impression of a newly introduced brand of smoothie maker, In his talk at the Americ

Super Act, based on the advertisement and a report from annual convention held at W

consumerist.com. An anthropomorphic representation of a George Medin argued that

brand was induced through the ad copy. Finally, participants ten, our character has set

were administered a suspicion probe; none of the partici- again. He reported num

pants reported awareness of a link between the two studies. showing that people "age

the foundation or enduring dispositions.

Stimulus Materials

(Incremental theory)

We manipulated brand anthropomorphization in two ways:

by representing a product with humanlike elements and by 'n his talk at the American Psychological Associati

using first person to describe the product (Figure 2, Panel annual convention held at Washington D.C. in August, Dr

^ , . , , ,. George Medin argued that no one s character is as'hard

A). For the manipulation check on anthropomorphism, we as a ^

conducted a pretest (n — 57). Participants first provided greater eff

their degree of agreement with the following statements: "It changes." H

seems almost as if SuperAct has (1) its own beliefs and ies showing th

desires, (2) consciousness, (3) a mind of its own" (1 = acter- He also

"strongly disagree," and 7 = "strongly agree"). The last people s perso

thpir líítf* sixtipi

item then required participants to rate the extent to which

SuperAct had come alive (like a human). We summed the After reading the article, participants indicated their opin

responses to these items. As we expected, participants in the ions on a seven-point scale with two items that best

anthropomorphized brand condition indicated that the brand reflected their views of the article, to ensure that the article

seemed more like a human than those in the nonanthropo- in both conditions was equally persuasive and clear. We

morphized brand condition (a = .90; Mamh = 4.17, Mnonanth = averaged the responses to these two items (r = .54, p < .05)

3.06; F(l, 55) = 8.57, p < .05). Differences between the and found no statistical differences across conditions (F <

humanized and the nonhumanized brand conditions did not 1). To check whether reading the article induced the appro

86 / Journal of Marketing, May 2013

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FIGURE 2

Manipulations of Anthropomorphized Versus Nonanthropomorphized Brands

A: Experiment 2a

It is the most reliable and leading brand of „ j am t^e nwst rejjable and leading brand of

smoothie maker on the market. Superiorly ■ smoothie maker on the market. I am superiorly

equipped with 500 watts of power, Super ACT equipped with 500 watts of power to efficiently

smoothie maker efficiently turns ice cubes turn ice cubes and frozen fruit into creamy

and frozen fruit into creamy smoothies and j I f smoothies and pureed soups. I hare a

pureed soups. Its revolutionary CycloneCreator m revolutionary CycloneCreator blending system that

blending system continuously pushes any mix- JL continuously pushes any mixture down to the

tore down to the blade level, resulting in jjfAt blade level, resulting in chunk-free smoothies

chunk-free smoothies every time. Supper Act's every time. Iffy innovative RazorTech stainless

innovative RazorTech stainless-steel blades steel blades slice through the thickest fruits and

slice through the thickest fruits and vegeta- vegetables and are guaranteed for life,

bies and are guaranteed for life.

www.snperact.com

www.saperact.com

Nonanthropomorphized Anthropomorphized

B: Experiment 2b

Zelt! Hey, my name is Zelt!

I am the most reliable and leading brand of steam

It is the most reliable and leading brand of steam

irons on the market. I have a very high, continuous

irons on the market. It has a very high, continuous

steam output, an extra powerful shot of

steam output, an extra powerful shot of

concentrated steam, elongated steam slots, as well

concentrated steam, elongated steam slots, as well

as special safety features. My electronic safety

as special safety features. The electronic safety

shut-off will activate when I am left unattended. I

shut-off will activate when it is left unattended. It

also have changeable anti-calcium steam iron

also has changeable anti-calcium steam iron

cartridges. My cord is 9 feet long and allows for

cartridges. Its cord is 9 feet long and allows for

maximum reach. You will also enjoy my soft handle

maximum reach. You will also enjoy its soft handle

for lasting ironing comfort!

for lasting ironing comfort!

Zelt

Zelt

www.zelt.com

www.zelt.com

Nonanthropomorphized Anthropomorphized

priate theory view, we asked participants to make predic- who read the

tions about four target people's behaviors in a particular sit- 78.21, Min

uation on a probability scale from 0 to 100. Chiu, Hong,

Measures

and Dweck (1997) find that people induced with the entity

theory mind-set make stronger predictions of behaviors We measured attitude toward the brand w

across situations given a specific trait. As expected, we (a = .94) as in Experiments la and lb. We

found that participants who read the article about stable per- brand responsibility on a seven-point Lik

sonality traits attributed higher probabilities of future three items (a = .67). After completing t

behaviors that were consistent with a given trait than those sures, participants reported their inv

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wrong 18

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

information from the report and the extent to which the -2.84, p < .05). In the same regression equation as in the

information was negative. third step, the moderation effect of implicit theory dropped

to nonsignificance when we introduced the mediator (i.e.,

Results

brand responsibility) into the model ((3 = -.59, t(4, 98) =

Manipulation checks. Participants viewed the con- -1.29,/? > .10). Thus, brand responsibility fully m

sumerist.com report as providing negative information the effect of the interaction between brand anth

about the brand (M = 5.17; 1(102)^from 4 = 8.53,p < .05). phization and implicit theory. The Sobel test also c

Their involvement with the information in the article (r = that brand responsibility fully mediates the m

.69, p < .05) was not statistically different across ad types effect of implicit theory (z = -2.14, p < .05).

(p > .10).

Hypothesis tests. We performed a 2 (implicit theory Experiment 2b

manipulation: entity, incremental) x 2 (brand anthropomor- T r • .n. • . •

... , . : In Experiment 2b, we aim to increase the external validity

phization: anthropomorphized brand, nonanthropomor- ^ .. ., ,. c c

. , , „ , . r ■ , , , of our findings by replicating the results of Experiment 2a

phized brand) analysis of variance on attitude toward the ^ a direct measure of i

brand. The results revealed a significant interaction between ^ ^ {h In addl

implicit theory and brand anthropomorphization (F(l, 99) = underlying process of why e

4.19,/? < .05). We followed up with an analysis of planned mental theorists> have more

contrasts. Participants who were induced with an entity anthropomorphized brand t

theory stance had less favorable brand attitudes when they caused by ^ product wrongd

were exposed to the anthropomorphized brand advertise- ousl>, because entity theorist

ment and later read the negative brand report than those factors (Dweck and Molden

who were exposed to the nonanthropomorphized brand attribute the cause of negati

advertisement (Manth - 3.46, Mnonanth - 4.14, F(l, 99) - rather than to external factor

4.34, p < .05). In contrast, participants who were induced directly measure the extent t

with incremental theory exhibited no statistical differences mental theorists attribute the c

in brand attitude regardless of whether they were exposed to t0 a brand rather than to exte

the anthropomorphized or the nonanthropomorphized brand empirically test whether entity

fy? > 10). As we expected, no statistical differences emerged ca]dy and stability of a ne

between entity and incremental theorists for the nonanthropo- higher than those of incremen

morphized brand (p > .10). Table 1 provides a complete set our theorizing regarding what ma

of results. A graphic representation appears in Web Appen- theorists different. Finally, we

dix W3 (www.marketingpower.com/jm_webappendix). bility that the results are driv

Process variables. An analysis based on Baron and ceived diagnosticity of negative in

Kenny (1986) revealed (1) a significant moderating effect and incremental theorists. Fig

of implicit theory on the relationship between brand anthro- ceptual model for Experiment

pomorphization and brand responsibility (F(l, 99) = 7.55,/?

< .05), (2) a significant effect of brand responsibility on

Participants, Design, and Procedure

attitude toward the brand (F(l, 101) = 11.66, p < .05), and One hundred forty-six underg

(3) a significant effect of brand responsibility on attitude East Coast university participated

toward the brand when we included the interaction among participants viewed one of tw

brand anthropomorphization (independent variable), (i.e., an anthropomorphized and

implicit theory (moderator variable), and brand responsibil- brand). This was followed by a n

ity (mediation variable) in the model ((3 = -.29, t(4, 98) = wrongdoing. Second, participan

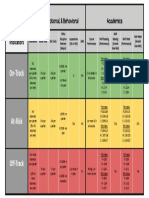

TABLE 1

Cell Means and Standard Deviations in Experiments 1a, 1b, and 2a

Experiment 2a

Experiment 1a Experiment 1b Entity Theorists Incremental Theorists

AB NAB AB NAB AB NAB AB NAB

(n = 21) (n = 18) (n = 20) (n = 20) (n = 28) c; II CM

C, II CM

(n = 26)

Attitude toward the brand 3.04 3.84 2.48 3.35 3.46 4.14 4.04 3.79

(.93) (1.02) (.91) (1.37) (1.07) (1.24) (1.13) (1.17)

Brand trust 2.52 3.39 2.15 3.00

(1.01) (1.18) (.76) (1.33)

Brand responsibility 5.05 3.94 4.58 4.65

(.89) (.95) (1.14) (1.31)

Notes: AB = anthropomorphized brand; NAB = nonanthropomorphized brand. Standard deviations are in parentheses.

88 / Journal of Marketing, May 2013

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FIGURE 3

Conceptual Model for Experiments 2a and 2b: A Mediated Moderation

Brand Responsibility

Attributions of the cause of a negative brand performance

Stability of a negative brand performance

Typicality of a negative brand performance

Brand anthropomorphization

(anthropomorphized vs.

nonanthropomorphized) x Attitudes toward the brand

implicit theory

(entity vs. incremental)

with dependent, process, and manipulation check variables. to which participants viewed the negative incident as typi

After completing the main dependent and process variables, cal of the brand. We assessed belief in implicit versus incre

participants answered filler questions on their interests and mental theories of personality using the implicit persons

activities. Embedded in this portion of the survey were theory measure (Levy, Stroessner, and Dweck 1998; Park

items measuring the implicit theories about the malleability and John 2010). That is, participants indicated their agree

of human characteristics. The study concluded with a brief ment with eight statements, four of which were representa

demographic section and an open-ended suspicion probe; tive of entity theory (reverse coded in computing the index

none of the participants guessed the true nature of the study. of implicit theory) and four of which were representative of

incremental theory, on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 =

Stimulus Materials and Pretest

'strongly disagree," and 7 = "strongly agree"). We averaged

We used a fictitious brand of steam irons, Zelt. We manipu- the responses to these eight items to create an imp

lated brand anthropomorphization with the combination of son theory index for each participant (a = .8

visual and verbal humanlike elements similar to that of scores indicated a stronger belief in incremen

Experiment 2a (Figure 2, Panel B). For the manipulation (Park and John 2010). We assessed the first m

check on anthropomorphism, we conducted a pretest (n = diagnosticity (Ahluwalia, Burnkrant, and Unnav

46), in which participants in the anthropomorphized brand percentages of high- and low-quality steam i

condition perceived the brand to be a human to a greater to ^ave a problem with the target attribute (i.e.,

extent than those in the nonanthropomorphized brand con- ^e adapted the second measure of diagnost

dition (a = .81; Manth = 4.39, Mnonanth = 3.55; F(l, 44) = Ahluwalia (2002), with a three-item, seven-point

6.43, p < .05). No differences emerged in participants' atti- differential scale (a = .76; for details, see the Ap

tudes toward the brand (a = .93; Manth = 4.67, Mnonanth =

Results

4.33) or in their perceptions of ad believability (a = .91;

M^th = 5.20, Mnonan,h = 4-88) between the two types of Manipulation checks. One-sample t-tests show

brand positioning (ps > .10). Negative information about participants viewed the consumerist.com report

the Zelt brand's performance appeared in a consumerist. ing negative information about the Zelt brand (

com report (Web Appendix W2 at www.marketingpower. t(145)d¡ff from 4 = 10.80, p < .05). Participants' in

com/jm webappendix). with the information in the article did not differ stat

across ad types (p > .10). As we intended, participants per

Measures ceived the Zelt brand as more humanized in the anthropo

We measured attitude toward the brand (a = .94), brand morphized brand condition

responsibility (a = .76), perceptions of a brand as anthropo- ^44) = ®-74, P <

morphized (a = .93), and involvement with the information Brand attitude. We co

in the article (r = .71, p < .05) with the same items as in analysis to test our predict

Experiment 2a. We gauged attributions of the cause of a ates the negative effect of

negative brand performance by asking participants to alio- consumers' brand attitudes. T

cate the percentage of the problem that was due to the brand mental condition (0 = bran

rather than to other external factors (Klein and Dawar brand anthropomorphizat

2004). Next, we measured the stability of a negative brand (continuous variable), and

performance with two items on a seven-point Likert-type theory and brand anthr

scale (r = .28,p < .05; Klein and Dawar 2004). We assessed variables (Park and John 2

the typicality of a negative brand performance as the extent the implicit theory scale b

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wro

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

person's score to eliminate multicollinearity (Aiken and manee ((3 = .06, t(142) = 2.17, p < .05), the perceptions of

West 1991). Consistent with the results of the previous typicality ((3 = .38, t(142) = 2.55, p < .05), and the stability

experiments, the analysis showed a significant effect of of a negative brand performance (¡3 = .28, t( 142) = 2.17,p <

brand anthropomorphization ((3 = .36, t(142) = 2.07, p < .05). Entity theorists attributed a higher percentage of the

.05). The interaction between brand anthropomorphization problem to the anthropomorphized brand than their incre

and implicit theory was also significant ((3 = -.32, t(142) = mental counterparts ((3 = -.05, t(142) = -2.42, p < .05).

-2.05,p < .05). Web Appendix W3 (www.marketingpower. They also viewed the anthropomorphized brand's negative

com/jm_webappendix) presents the interaction graph plot- performance as more typical of the brand (P = -.21, t(142) =

ted at one standard deviation below the mean of the implicit -2.23,p < .05) and as more stable (P = -.16, t(142) = -1.98,

theory measure (-1 SD; entity theorists) and one standard p < .05) than incremental theorists. Entity theorists also

deviation above the mean of the measure (+1 SD; incre- attributed the cause of the negative performance to a brand

mental theorists) by substituting these values into the to a greater extent when it was humanized than when it was

regression equation (Cohen and Cohen 1983). To gain addi- not (-1 SD; P = -.13, t(142) = -2.78,p < .05) and perceived

tional insight into the nature of this interaction, we tested an anthropomorphized brand's negative performance as

simple slopes at values one standard deviation above and more typical (-1 SD; P = -.67, t(142) = -2.81, p < .05) and

below the mean score of the implicit theory measure (Aiken more stable (-1 SD; P = -.72, t(142) = -3.54, p < .05) than

and West 1991; Park and John 2010). We found that partici- that of a nonanthropomorphized brand. Furthermore, no

pants with an entity theory view had less favorable attitudes significant interaction occurred between brand anthropo

toward the brand when they saw the anthropomorphized morphization and implicit theory for both diagnosticity

brand advertisement and later read the negative brand report measures (ps > .10). This ruled out an alternative explana

tion those who were exposed to the nonanthropomorphized tion that entity theorists viewed information about a nega

brand advertisement (-1 SD; P = .72, t( 142) = 2.93, p < tive performance of an anthropomorphized brand as more

.05). However, no significant differences emerged for diagnostic than incremental theorists,

respondents with an incremental theory belief (+1 SD; p = jn addition, participants' attributions of the cause of a

-.01, t(142) = -.03,p > .10). negative performance predicted their attitudes toward the

Brand responsibility as a process. An analysis based on brand (P = -1.32, t( 144) = -3.06, p < .05). When we

Baron and Kenny (1986) showed that brand responsibility regressed attitude toward the brand on brand anthropomor

fully mediates the moderating effect of implicit theory of phization, implicit theory, the interaction between them,

personality, as evidenced by (1) a significant effect of the and the attributions of the cause, the interaction term

interaction between brand anthropomorphization and became nonsignificant. The attributions of the cause of a

implicit theory on brand responsibility (P = .42, t(142) = negative brand performance served as a full mediator for

2.51,p < .05); (2) a significant effect of brand responsibility attitudes toward the brand (Sobel's z = -1.79, p < .05). In

on attitude toward the brand (F(l, 144) = 10.26, p < .05); addition, our analysis indicated that stability and typicality

(3) brand responsibility emerging as a significant factor that of a negative brand performance did not mediate the inter

affects brand attitude when we included brand anthropo- action effect of brand anthropomorphization and implicit

morphization, implicit theory, the interaction between brand theory on attitudes toward the brand,

anthropomorphization and implicit theory, and brand

responsibility (as a mediation variable) in the model (P = Discussion

-.17, t( 141 ) = -2.25,p < .05); and (4) the moderation effect Taken together, the results of Experiments 2a and 2b pro

of implicit theory dropping to nonsignificance when we vide convergent evidence that implicit theory of personality

included brand responsibility in the model (P = -.25, t(141) = moderates the effect of brand anthropomorphization. As we

-1.57, p > .10). The Sobel test also confirmed that brand hypothesized, for entity theorists, negative publicity caused

responsibility fully mediates the effect of the interaction by a product wrongdoing leads to less favorable attitudes

between brand anthropomoiphization and implicit theory (z = when a brand is anthropomorphized than when it is not.

-1.98; p < .05). In addition, brand responsibility fully medi- However, for incremental theorists, negative brand informa

ates the main negative effect of brand anthropomorphiza- t¡on ^oes not jeacj t0 more detrimental evaluations of an

tion (Sobel s z - 1.78,p < .05). anthropomorphized brand than a nonanthropomorphized

Exploring the underlying process further. We conducted brand. In addition, consistent with our theoretical argument

a series of multiple regression analyses to test whether par- that an anthropomorphized entity is perceived as intentional

ticipants' attributions of the cause of a negative brand per- and mindful and therefore is attributed greater responsibil

formance, typicality of a negative brand performance, sta- ity for its behaviors, our results show that brand responsibil

bility, and diagnosticity of a negative brand performance ity serves as a mediator for the effect of the interaction

underlie the differences in brand attitudes across anthropo- between brand anthropomorphization and implicit theory of

morphized and nonanthropomorphized brand conditions. personality. Experiment 2b adds additional empirical sup

We expected support for our predictions to emerge in the port for our theorizing, such that entity theorists perceive a

form of a significant interaction between implicit theory product wrongdoing as more typical of a brand than incre

and brand anthropomorphization for these dependent mental theorists. Entity theorists also endorse more internal

variables. The interaction terms were significant for partici- attributions and attribute the negative publicity to more sta

pants' attributions of the cause of a negative brand perfor- ble causes than their incremental counterparts.

90 / Journal of Marketing, May 2013

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Th© Role Of Firm Rosponso contrast. both apology and compensation responses

QtratPfliPQ convey the intent to avoid wrongdoings in the future (Ferrin

9 et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2004). Because people generally

The idea that entity and incremental theorists form different have more favorable impressions of a wrongdoer after

beliefs about the stability of a negative brand performance receiving an apology (Kim et al. 2004) or compensation

suggests that firms' strategic responses to product wrong- (Bottom et al. 2002), we expect both entity and incremental

doings may be more or less effective in combating negative theorists to have more positive evaluations of a nonanthro

brand information. Although firms can respond to product pomorphized brand after they receive an apology or com

wrongdoings in various ways (Dawar and Pilluda 2000; pensation. Because incremental theorists believe in positive

Kim et al. 2004; Siomkos and Kurzbard 1994), we focus on change, the apology and the compensation should lead to

three particular firm responses: denial, apology, and com- more favorable evaluations of an anthropomorphized brand

pensation. We define a denial response as a strategy in as well. Thus, we expect no differences in incremental theo

which a firm forsakes any responsibility of wrongdoing by rists' postapology and postcompensation attitudes toward and

declaring the untrue nature of an allegation (Kim et al. purchase intentions of either a humanized or a nonhumanized

2004). Thus, the denial does not ensure that that the wrong- brand. Yet we expect a different pattern of results for entity

doing will not happen again (Dutta and Pullig 2011). An theorists exposed to anthropomorphized brands. Entity the

apology response reflects a strategy in which a firm accepts orists are likely to be more insensitive to the apology

responsibility and expresses remorse; this involves a state- response when a brand is humanized because they believe

ment that ensures the prevention of a future wrongdoing that things do not change (Haselhuhn, Schweitzer, and

(Kim et al. 2004). Finally, a compensation response refers Wood 2010). Thus, they are likely to retain their less favor

to a firm strategy that includes all elements of the apology able attitudes toward and purchase intentions of an anthro

response but also adds a monetary reward and/or product pomorphized (vs. a nonanthropomorphized) brand on receiv

replacement for a product wrongdoing (Coombs and Holla- 'n8 the apology.

day 2008). Prior research has established that substantive However, we anticipate that compensation alters entity

amends (e.g., monetary reward) that complement a promise theorists' post-firm response attitudes toward and purchase

to avoid future wrongdoings provide a stronger indication intentions of an anthropomorphized brand. This outcome is

of an intent to prevent future violations (Bottom et al. anticipated because entity theorists are able to revise their

2002). Thus, compensation is a stronger response than an initial impressions in the face of overwhelming counterfac

apology in terms of providing assurance of avoiding a tua' information (Plaks et al. 2001). Plaks et al. (2001)

future product wrongdoing show that entity theorists who initially formed poor expec

Prior research has also established that denial does not tations of a target (i.e., poor academic performance) were

effectively restore attitudes toward the wrongdoer, because insensitive to a moderate amount of counterfactual informa

it signals an unwillingness to initiate a problem resolution tion (i e" Sood Performance on a test). However, when

(Kim et al. 2004; Raju and Rajagopal 2008). In this regard, ffced with excellent Performance on a test, they changed

denial of a wrongdoing can be harmful to a firm, because it tdeir Perceptions of the target and even made predictions of

c -, . • . . . . . .. , , . the target s outstanding performance in the future. These

tails to convey an intent to prevent a potential wrongdoing & ■ u , . „ .

findings suggest that entity theorists do not inflexib

in the future (Ferrin et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2004; Raju and

to their initial trait-based impressions but rather revise

Rajagopal 2008), and thus, both entity and incremental con

. . . , , . . . when confronted with a significant amount of counterinfor

sumers attitudes toward and purchase intentions of a T . , ....

, , . , mation. In this regard, prior research suggests that a com

nonanthropomorphized brand are likely to decrease ,n the ion se constitutes rel

face of such a response. Incremental theorists are also more a commitment t0 avoid wrongdoi

likely to be negatively affected by an anthropomorphized (Dirks gt a| 2m) Therefore, we posit th

brand s denial response because they expect the brand to ^ ^ t0 change their perceptions of a

perform better in the future. However, instead, they do not more posltive> sta51e state, which leads t

receive any indication of future change. Thus, because postcompensation attitudes toward and p

incremental theorists postdenial attitudes toward and pur- 0f an anthropomorphized brand. Thus,

chase intentions of both an anthropomorphized and a postcompensation attitudes toward and

nonanthropomorphized brand are likely to decrease, we Df bodl an anthropomorphized and a n

expect no differences in their post-firm response attitudes and phized brand increase compared with t

purchase intentions between humanized and nonhumanized evaluations, their less favorable pr

brands. In contrast, entity theorists view an anthropomor- toward and purchase intentions of an

phized brand's negative performance as stable. Because the (vs. a nonanthropomorphized) brand ar

denial indicates no change in a brand's future performance, For entity theorists, we hypothesize

entity theorists' attitudes toward and purchase intentions of .... . , ,. ,

....J i-... • ... h Hi- Denial and apology responses to negative brand ínforma

a humanized brand are likely to remain the same. Overall, tion cau$ed £ a

we expect entity theorists postdenial attitudes toward and abje attitudes to

purchase intentions of an anthropomorphized brand to be pomorphized bra

less favorable than their attitudes toward and purchase H3b: A compensation

intentions of a nonanthropomorphized brand. caused by a product wrongdoing results in no differences

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wrong 191

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

in attitudes toward and purchase intentions of either an ing participants to complete a short filler survey that lasted

anthropomorphized or a nonanthropomorphized brand. approximately ten minutes. We did so to rule out the possi

bly: A denial response to negative brand information caused bility that the negative brand information following imme

by a product wrongdoing results in no change (compared diately after the stimulus advertisement would prime a

with preresponse) in attitudes toward and purchase inten- , , n .. . < -j

r 5. ,. ,, , T negative human schema. Participants were asked to provide

tions of anthropomorphized brands. In contrast, a denial ® r . . .

response to negative brand information caused by a prod- their overall atti

uct wrongdoing results in less favorable attitudes toward brand (i.e., pre-

and purchase intentions of (compared with preresponse) to manipulation c

nonanthropomorphized brands. consumerist.com report tha

H3d: An apology response to negative brand information to the product

caused by a product wrongdoing results in no change marketingpower.com

(compared with preresponse) in attitudes toward and pur- of n tjve brand

chase intentions of anthropomorphized brands. In con- , . , .... ., .. .

trast, an apology response to negative brand information same t0 fVOld

caused by a product wrongdoing results in more favor- reported their at

able attitudes toward and purchase intentions of (com- the brand (i.e.,

pared with preresponse) nonanthropomorphized brands. cated their perce

il^: A compensation response to negative brand information formance and a

caused by a product wrongdoing results in more favor- the end of the su

able attitudes toward and purchase intentions of (com- embedded among o

pated with preresponse) both anthropomorphized and completed a d

nonanthropomorphized brands. r , . . , . . . .. . . .

were administered a suspicion

For incremental theorists, we hypothesize the followin

H4a: Denial, apology, and compensation responses to negative

Stimulus Materials and Pretests

brand information caused by a product wrongdoing result

in no differences in attitudes toward and purchase inten- We used a fictitious brand of a three-dimensiona

tions of either an anthropomorphized or a nonanthropo- digital camera, Zook. We manipulated brand anthr

morphized brand. phization in the same way as in Experiments 2a an

H4b: A denial response to negative brand information caused (R 4) Qur manipulation of negatiVe brand inform

by a product wrongdoing results in less favorable atti- . _ . . , . , ,

tudes toward and purchase intentions of (compared with aPPears ln Web A

preresponse) both anthropomorphized and nonanthropo- on anthropomorp

morphized brands. Participants in the anthropomorphized brand condition per

H4c: Apology and compensation responses to negative brand ceived the brand to be human to a greater extent than

information caused by a product wrongdoing result in in the nonanthropomorphized brand condition (a

more favorable attitudes toward and purchase intentions = 4.09, Mnonanth = 2.65; F(1,51) = 11.70,p < .0

of (compared with preresponse) both anthropomorphized differences emerged in participants' attitudes toward the

and nonanthropomorphized brands. (a = ^ ^ = ^ = ^ jn ^ percep_

tions of ad believability (a = .85; Manth = 4.18, Mnonanth =

Experiment 3 4.44) between a humanized and a nonhumanized brand

We conducted Experiment 3 with two objectives in mind. positioning {ps> .10).

First, we wanted to replicate the results of Experiments 2a Measures

and 2b in a different product category (i.e., a digital camera)

and to increase the managerial relevance of the study by measured preresponse (a = .92) and postresponse (ot =

adding a new brand performance measure that is closer to -^7) attitudes toward the brand, stability of a negative brand

actual buying behavior (i.e., purchase intentions). Second, performance (postresponse), involvement with the negative

Experiment 3 explores which response strategies firms can information in the article (r = .75, p < .05), and perceptions

use to reduce the adverse effects of negative brand publicity. °f a brand as anthropomorphized (a = .82) with the same

items as in Experiment 2b. We measured preresponse (r =

Participants, Procedure, and Measures .55, p < .05) and postresponse (r = .73, p < .05) purchase

Three hundred seventeen undergraduate students at a pri- intentions with two items on a seven-point Likert-type

vate East Coast university participated in this study. We scale- We also combined the implicit person theory (Levy,

employed a 2 (brand anthropomorphization: anthropomor- Stroessner, and Dweck 1998) measures into the scale (a =

phized, nonanthropomorphized brand) x 3 (firm responses: -^)- AH measures appear in the Appendix.

denial, apology, compensation) x 2 (pre-, post-firm

Results

response measures) factorial design; we also included a

scale to measure implicit theory. The experiment consisted Manipulation checks. Participants perceived the artic

of two parts. In the first part, the procedure was similar to providing negative information (M = 5.14; t(315)diff from

that of Experiment 2b; the only difference was that we sep- 15.44,p < .05). Their involvement while reading the negati

arated the presentation of the advertisement in time from consumerist.com report did not differ across ad types (p >

the presentation of the negative brand information by ask- .10). They viewed an anthropomorphized brand as a human

92 / Journal of Marketing, May 2013

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FIGURE 4

Manipulations of Anthropomorphized Versus Nonanthropomorphized Brands: Experiment 3

ZOOK! Hey, my name is ZOOK!

It is the most reliable and leading

I am the most reliable and leading

brand of 3D HD digital cameras on

brand of 3D HD digital cameras on

the market. It provides you with a

the market. I provide you with a total

total 3D HD imaging system that will

3D HD imaging system that will

change the way you take and enjoy

change the way you take and enjoy

photos, from the advanced 3D HD

photos, from my advanced 3D HD

digital camera to the stunning 3D

digital camera to my stunning 3D HD

HD digital viewer and breakthrough

digital viewer and breakthrough 3D

3D HD printing technology. These 3D

HD printing technology. My 3D

images capture breathtaking

images capture breathtaking

moment and natural beauty. It

moment and natural beauty. I make

makes images that once were only a

images that once were only a dream

dream now a reality™.

now a reality™.

ZOOK

ZOOK

www.ZOOK.com

www.ZOOK.com

Nonanthropomorphized Anthropomorphized

to a greater extent than a nonanthropomorphized brand -.02, t(313)

(Manth = 3.89, Mnonanth = 3.36; F(1, 315) = 10.99, p < .05). a nonanthr

In the denial, apology, and compensation response condi- Explorator

tions, 103 (of 117), 81 (of 91), and 99 (of 108) participants, more, we r

respectively, indicated that Zook denied, apologized for, postresponse

and provided compensation for the quality issues of its 3D variables (i

photos. centered), brand anthropomorphization, firm response type,

Hypothesis tests. As an indication of the robustness of and their interactions as predic

the negative effect of brand anthropomorphization, the P^e sl°Pe analysis showed that

results for the preresponse attitude toward and purchase response, entity theorists had le

intentions of the brand confirmed the pattern consistent H SD' P = -72' l(306) = 24

with the predictions of H2. That is, compared with the intentions of (-1 SD; (3 = .7

, . , , , . , . , anthropomorphized than a nonanthropomorphized brand,

nonanthropomorphized brand, the anthropomorphized v 1

, , ... , ,a ,, .. „„ The same pattern occurred when a firm responded with the

brand led to less favorable attitudes (p = .56, t(313) = 5.09, , 1 , , . , . , . .r . , __ a

... . . ,n cn apology, such that entity theonsts attitudes (-1 SD; p =

p < 05) and lower purchase intentions ((3 = ^59, t(3

4.10, p < .05) when participants were exposed to negative SD; p = , 37> t(306) = 3.44

publicity. The effect of the interaction between brand bmnd was human¡zed Howe

anthropomorphization and implicit theory was also sigmfi- ¿n attUudes (_j SD; p =

cant for both attitudes (|3 = -.39, t(313) = ^1.06, p < .05) chase intentions (_j S

and purchase intentions (¡3 = -.53, t(313) = -4.22,p < .05). between the two types of

Simple slope tests confirmed that entity theorists had lower entity theorists when a bran

attitudes toward (-1 SD; (3 = 1.15, t(313) = 6.28, p < .05) ¡ts product wrongdoing. W

and lower purchase intentions of (-1 SD; |3 = 1.41, t(313) = attitudes toward (denial:

5.81, p < .05) an anthropomorphized than a nonanthropo- .10; apology: +1 SD; (3 = .1

morphized brand. For incremental theorists, no significant pensation: +1 SD; p = -.38

differences emerged in attitudes toward (+1 SD; P = .11, chase intentions of (denial

t(313) = .72,/? > .10) or purchase intentions of (+1 SD; P = .10; apology: +1 SD; P = .2

When Humanizing Brands Goes Wron

This content downloaded from

122.176.241.192 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 15:24:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

pensation: +1 SD; (3 = -.03, t(305) = -.01, p > .10) either a purchase intentions (i.e., calculated as the difference

humanized or a nonhumanized brand for incremental theo- between pre- and postresponse attitudes/purchase inten

rists for all three responses. tions) as the dependent variable. The results indicated that

Next, to test our hypotheses regarding pre- and post- the interaction contrast was significant for entity theor

response changes in attitudes and purchase intentions, we (attitudes: F(l, 305) = 4.36, p < .05; purchase intention

performed a series of three-way repeated measures analyses F(l, 305) = 4.04, p < .05); brand humanization led to l

of variance with the median split of the implicit theory mea- attitude change in the apology response. However, changes

sure. As we predicted, for entity theorists, when a firm occurred in attitudes and purchase intentions for bo

responded with either a denial or an apology, no significant anthropomorphized and nonanthropomorphized brand

changes occurred in either postresponse attitudes toward the compensation response. Conversely, the interaction c

(F(l, 305)denial = 2.00, p > .10; F(1, 305)apo,ogy = 2.94, p > trast for incremental theorists was nonsignificant (attitudes:

.08) or postresponse purchase intentions of (F(l, 305)denial = F(F 305) = 1.27, p > .10; purchase intentions: F(l, 305)

.16,p > .10; F(l, 305)apology = 1.31,p > .10) a humanized .05,p> .10).

brand. However, when a firm responded with a denial, we Supplementary analysis. A series of multiple regressio

observed a significant decrease in incremental theorists analyses showed that for entity theorists, postresponse

attitudes (F(l, 305) = 6.75,p < .05) and purchase intentions bility perceptions were not significantly different betw

(F(l, 305) = 5.13, p < .05) when they were exposed to an an anthropomorphized and a nonanthropomorphized bran

anthropomorphized brand. We observed a similar pattern when the firm used the denial response (-1 SD; |3 = -.09

for both entity theorists (attitude: F(1, 305) = 4.52, p < .05; t(306) = -.99, p > .10). There were also no significant

purchase intentions: F(l, 305) = 5.14, p < .05) and incre- ferences between entity and incremental theorists in ter

mental theorists (attitude: F(l, 305) = 9.16, p < .05; pur- 0f stability perceptions (-1 SD; [3 = .23, t(305) = 1.58,p

chase intentions: F(l, 305) = 6.62,p < .05) when they were .10), which is in contrast to the preresponse stability pe

exposed to a nonhumanized brand. In contrast, when incre- ceptions; entity theorists had higher perceptions of stability

mental theorists were exposed to either a humanized or a 0f a brand's negative performance than their incremen

nonhumanized brand, the apology response increased their counterparts. This result supports our theoretical argument

attitudes (F(l, 305)anth = 10.73, p < .05; F(l, 305)nonanth = that denial does not affect perceptions of stability for entity

6.40,p < .05) and purchase intentions (F(l, 305)anth = 4.67, theorists who are exposed to an anthropomorphized bran

p < .05; F(l, 305)nonanth = 5.37, p < .05). Entity theorists' however, denial increases incremental theorists' view

postapology attitudes (F(l, 305) = 10.82, p < .05) and pur- stability. Furthermore, when a firm responded with

chase intentions (F(l, 305) = 4.03, p < .05) also increased apology, we found that stability of a negative brand perf

when they were exposed to a nonanthropomorphized brand. manee followed the same pattern as in Experiment 2b. That

For both entity and incremental theorists, the compensation is, for entity theorists, stability perceptions were higher f

response led to more favorable postresponse attitudes an anthropomorphized than a nonanthropomorphized bran

toward (F(l, 305)entity anth = 66.76, p < .05; F(l, 305)entity (-1 SD; (3 = -.73, t(305) = 2.26,p < .05). Their perception

nonanth = 31.58, p < .05; F(1, 305)incremental anth = 40.37, p < of stability of an anthropomorphized brand were also hig

.05; F(l, 305)incremental nonanth = 12.03, p < .05) and higher than those of incremental theorists (|3 = -.32, t(305

postresponse purchase intentions of (F(l, 305)entity anth = -2.39, p < .05). Finally, entity theorists' perceptions of

34.37, p < .05; F(l, 305)entity nonanth = 6.91, p < .05; F(l, bility of a brand's wrongdoing significantly decreased wh

305)incremental anth = 10.59, p < .05; F(l, 305)incremental a fi1™ used the compensation response (-1 SD; (3 = -.76

nonanth = 10.00, p < .05) both anthropomorphized and t(305) = -2.42, p < .05). This result is in accord with our

nonanthropomorphized brands. To empirically support our argument that when faced with strong countervailing