Professional Documents

Culture Documents

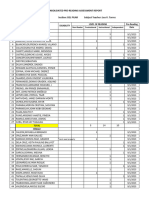

Allen Adrian G. Acosta Bpa 3A

Uploaded by

Allen AcostaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Allen Adrian G. Acosta Bpa 3A

Uploaded by

Allen AcostaCopyright:

Available Formats

Allen Adrian G.

Acosta

BPA 3A

For me traditionally, public officials have been somewhat nervous about

discussing corruption openly. Over the past several years, however, I have been struck by the extent to

which world leaders are now willing to talk candidly about this problem. It is not just that the economic

costs have become self-evident. It is also because there is an increasing demand for change. I would like

to make three main points. First, while the direct economic costs of corruption are well known, the

indirect costs may be even more substantial and debilitating, leading to low growth and greater income

inequality. Corruption also has a broader corrosive impact on society. It undermines trust in government

and erodes the ethical standards of private citizens.Second, although corruption is an extraordinarily

complex phenomenon, I do not accept the proposition or the myth that it is primarily a “cultural”

problem that will always take generations to address. There are examples of countries that have

managed to make significant progress in addressing it in a relatively short time.Third, experience

demonstrates that a holistic, multi-faceted approach is needed—one that establishes appropriate

incentives and the rule of law, promotes transparency, and introduces economic reforms that reduce

opportunities for illicit behavior. Perhaps the most important ingredient for a successful anti-corruption

approach is the development of strong institutions, centered on a professional civil service that is

sufficiently independent from both private influence and political interference.

corruption undercuts savings. The illegal use of public funds to acquire assets abroad shrinks the

economy’s pool of savings that could otherwise be used for investment. corruption can perpetuate

inefficiency. Because an over-regulated economy provides opportunities for regulators to demand

bribes, corruption creates a strong incentive to delay economic liberalization and innovation.

The impact of corruption on social outclomes is also consequential. Social spending on education and

health is typically lower in corrupt systems. This, in turn, leads to higher child and infant mortality rates,

lower birth-weights, less access to education, and higher school dropout rate in the philippines. These

outcomes disproportionately affect the poor, since they rely more heavily on government services,

which become costlier due to corruption. Moreover, corruption reduces the income-earning potential of

the poor as they are less well-positioned to take advantage of it. For all these reasons, corruption

exacerbates income inequality and poverty care should be taken to ensure that an anti-corruption

campaign does not create such fear that public officials are reluctant to perform their duties. For

example, in circumstances where state-owned banks have extended a loan to a company that has

become insolvent, it is often in the interest of the bank, the debtor, and the economy more generally to

restructure the loan (which might include principal write-downs) in a manner that enables the company

to return to viability. Yet the Fund’s experience has been that, in some countries, the managers of state-

owned banks are simply afraid to engage in such negotiations. They fear that, if they agree to any debt

write-down, they will be prosecuted under the country’s corruption law for having wasted state assets—

even though a restructuring might actually enhance the value of the bank’s claim relative to the

alternative, the liquidation of the company.

Finally, although regulatory reform can promote simplicity and automaticity, there are certain functions,

such as bank supervision, where discretion will always be essential. For these reasons, regulatory reform

cannot be a substitute for the development of effective institutions.

You might also like

- Uncovering the Dirty Truth: The Devastating Impact of Corruption on American Politics"From EverandUncovering the Dirty Truth: The Devastating Impact of Corruption on American Politics"No ratings yet

- Unveiling Corruption Exposing the Hidden Forces That Shape Our WorldFrom EverandUnveiling Corruption Exposing the Hidden Forces That Shape Our WorldNo ratings yet

- Governance, Corruption, and Public Finance: An OverviewDocument18 pagesGovernance, Corruption, and Public Finance: An OverviewAbu Naira HarizNo ratings yet

- How Government Corruptions Can Affect The Program of DevelopmentDocument5 pagesHow Government Corruptions Can Affect The Program of DevelopmentJeremiah NayosanNo ratings yet

- How Corruption Exacerbates and Promotes PovertyDocument22 pagesHow Corruption Exacerbates and Promotes PovertyLeonardo GarzonNo ratings yet

- Examples of Thesis Statements On CorruptionDocument7 pagesExamples of Thesis Statements On CorruptionPayingSomeoneToWriteAPaperUK100% (2)

- Corruption and Economic Development: Stephen J. H. DeardenDocument14 pagesCorruption and Economic Development: Stephen J. H. DeardenKapil DandeNo ratings yet

- Cost of CorruptionDocument4 pagesCost of CorruptionharyaniNo ratings yet

- Economic Development by Combating Corruption 22Document4 pagesEconomic Development by Combating Corruption 22Uzair Khan YousAfzaiNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument64 pagesCorruptionHamna AnisNo ratings yet

- DA1 - Graft and CorruptionDocument8 pagesDA1 - Graft and CorruptionShaneBattierNo ratings yet

- Expose Anglais La CorruptionDocument8 pagesExpose Anglais La Corruptionkonekadjatou1996No ratings yet

- Corruption Speeds Development But Undermines DemocracyDocument3 pagesCorruption Speeds Development But Undermines DemocracyranasohailiqbalNo ratings yet

- EMPA 113 - Assignment IVDocument4 pagesEMPA 113 - Assignment IVKNo ratings yet

- Corruption: Causes, Consequences, and Agenda For Further ResearchDocument4 pagesCorruption: Causes, Consequences, and Agenda For Further ResearchSU MatiNo ratings yet

- Ethic and AccountabilityDocument3 pagesEthic and AccountabilityShahril BudimanNo ratings yet

- Summary ReportDocument3 pagesSummary ReportFloraine RocaNo ratings yet

- Arvin JainDocument51 pagesArvin Jainsaiful deniNo ratings yet

- Business Social Responsibility & Reducing CorruptionDocument2 pagesBusiness Social Responsibility & Reducing CorruptionJure Grace RomoNo ratings yet

- Myths About Governance and Corruption: Back ToDocument3 pagesMyths About Governance and Corruption: Back ToAkin AuzanNo ratings yet

- Bribery in BusinessDocument7 pagesBribery in BusinessJohn KiranNo ratings yet

- Corruption Bibliography Focuses on AsiaDocument15 pagesCorruption Bibliography Focuses on AsiaTaposh Owayez MahdeenNo ratings yet

- Corruption's Impact on Income Inequality in BangladeshDocument6 pagesCorruption's Impact on Income Inequality in BangladeshIkramul HoqueNo ratings yet

- Psychology of CorruptionDocument4 pagesPsychology of CorruptionLiezel LopegaNo ratings yet

- How corruption impacts work practicesDocument5 pagesHow corruption impacts work practicesStacy LieutierNo ratings yet

- Factors That Cause Corruption in Business, Government and EducationDocument4 pagesFactors That Cause Corruption in Business, Government and EducationGabriel KoresyNo ratings yet

- Corruption and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Growth in CameroonDocument24 pagesCorruption and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Growth in CameroonBeteck LiamNo ratings yet

- Running Head: BUSINESS CORRUPTION 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: BUSINESS CORRUPTION 1api-283803035No ratings yet

- Literaturereview rws2Document9 pagesLiteraturereview rws2api-283803035No ratings yet

- Anti Corruption CommissionsDocument22 pagesAnti Corruption CommissionsGaurav SinghNo ratings yet

- Corruption Beyond The Post Washington Consensus KhanDocument22 pagesCorruption Beyond The Post Washington Consensus KhanAditya SanyalNo ratings yet

- Empowerment: P IIIDocument19 pagesEmpowerment: P IIIJanry SimanungkalitNo ratings yet

- Causes and Effects of CorruptionDocument8 pagesCauses and Effects of CorruptionKashif KashiNo ratings yet

- Aquino - Comprehensive ExamDocument12 pagesAquino - Comprehensive ExamMa Antonetta Pilar SetiasNo ratings yet

- The Inside Job Post Viewing Questions - COMPLETEDocument9 pagesThe Inside Job Post Viewing Questions - COMPLETEDavid KaranuNo ratings yet

- Deepika ReportDocument51 pagesDeepika ReportMohit PacharNo ratings yet

- Fighting CorruptionDocument3 pagesFighting CorruptionVia Maria Malapote100% (1)

- Institution and Issues - Case StudyDocument4 pagesInstitution and Issues - Case StudyMarianne Fe AlzonaNo ratings yet

- Corruption in USDocument2 pagesCorruption in USabuumaiyoNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and Corruption: A Cross-Country AnalysisDocument31 pagesCorporate Governance and Corruption: A Cross-Country AnalysisAbrahamNo ratings yet

- 6335 - B-221 - Laurice Rose Isabel ADocument4 pages6335 - B-221 - Laurice Rose Isabel ALauitskieNo ratings yet

- Corruption in International BusinessDocument20 pagesCorruption in International BusinessZawad ZawadNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Corruption and Poverty: EconomyDocument2 pagesRelationship Between Corruption and Poverty: EconomyManuel Alejandro Zarabanda GomezNo ratings yet

- Causes of Corruption in Civil Services and Solutions to Overcome ItDocument9 pagesCauses of Corruption in Civil Services and Solutions to Overcome ItJeremy KohNo ratings yet

- How Officials Abuse Positions for Personal GainDocument3 pagesHow Officials Abuse Positions for Personal GainKing Rommel DavidNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument13 pagesCorruptionTieraKhairulzaffriNo ratings yet

- Causes and Consequences of CorruptionDocument21 pagesCauses and Consequences of CorruptionlebanesefreeNo ratings yet

- Individual Activit 7 - ZACARIA PDFDocument3 pagesIndividual Activit 7 - ZACARIA PDFNajerah ZacariaNo ratings yet

- Transparency and accountability critical for good governance and economic growthDocument3 pagesTransparency and accountability critical for good governance and economic growthErnest PaulNo ratings yet

- First Draft Foun 1013 Documented EssayDocument7 pagesFirst Draft Foun 1013 Documented EssayTiffany DunkleyNo ratings yet

- The Role of Business in Social and Economic DevelopmentDocument17 pagesThe Role of Business in Social and Economic DevelopmentWillyn Joy PastoleroNo ratings yet

- 4 - Many Shades of CorruptionDocument3 pages4 - Many Shades of CorruptionAliah MagumparaNo ratings yet

- Resolving Ethical Dilemmas and Corruption in the PhilippinesDocument15 pagesResolving Ethical Dilemmas and Corruption in the PhilippinesdesblahNo ratings yet

- Ethics: Introduction: Crack Ias Sample Notes For Gs Mains-IvDocument106 pagesEthics: Introduction: Crack Ias Sample Notes For Gs Mains-IvSrinivas MurthyNo ratings yet

- Procurement Research ProposalDocument17 pagesProcurement Research ProposalHellen Bernard Ikuyumba90% (21)

- Corrupion and Economic GrowthDocument12 pagesCorrupion and Economic GrowthMeshack MateNo ratings yet

- Corruption, Institutions and Economic Development: Toke S. Aidt April 6, 2009Document28 pagesCorruption, Institutions and Economic Development: Toke S. Aidt April 6, 2009Indriati TsaniyahNo ratings yet

- Sfarc Iftimi Robert Gabriel Anul II Examen Engleza Juridica IVDocument8 pagesSfarc Iftimi Robert Gabriel Anul II Examen Engleza Juridica IVSirgNo ratings yet

- 1.1. Why This Book?: More InformationDocument10 pages1.1. Why This Book?: More Informationkashifkhan38No ratings yet

- Exercise Chapter 2 IBM530Document3 pagesExercise Chapter 2 IBM530PATRICIA PAWANo ratings yet

- End of Schooling at the Village SchoolDocument7 pagesEnd of Schooling at the Village SchoolHelna CachilaNo ratings yet

- (Cont'd) : Human Resource ManagementDocument14 pages(Cont'd) : Human Resource ManagementMohammed Saber Ibrahim Ramadan ITL World KSANo ratings yet

- SociologyDocument3 pagesSociologyMuxammil ArshNo ratings yet

- Krishna Grameena BankDocument101 pagesKrishna Grameena BankSuresh Babu ReddyNo ratings yet

- On Insider TradingDocument17 pagesOn Insider TradingPranjal BagrechaNo ratings yet

- Acr-Emergency HotlinesDocument2 pagesAcr-Emergency HotlinesRA CastroNo ratings yet

- Jaiib Made Simple Legal & Regulatory Aspects of BankingDocument8 pagesJaiib Made Simple Legal & Regulatory Aspects of BankingChatur ReddyNo ratings yet

- Family Nursing Care Plan: NAME: CASTILLO, Nina Beleen F. CHN Section: 2nu03Document3 pagesFamily Nursing Care Plan: NAME: CASTILLO, Nina Beleen F. CHN Section: 2nu03NinaNo ratings yet

- Mastodon - A Social Media Platform For PedophilesDocument17 pagesMastodon - A Social Media Platform For Pedophileshansley cookNo ratings yet

- Psyche Arzadon Ans Key DrillsDocument11 pagesPsyche Arzadon Ans Key Drillsjon elle100% (1)

- UntitledDocument22 pagesUntitledArjun kumar ShresthaNo ratings yet

- PCL LT 1 Application and Agreement - A A - FormDocument6 pagesPCL LT 1 Application and Agreement - A A - FormAmrit Pal SIngh0% (1)

- The Main Departments in A HotelDocument20 pagesThe Main Departments in A HotelMichael GudoNo ratings yet

- Answers To Gospel QuestionsDocument4 pagesAnswers To Gospel QuestionsCarlos Andrés ValverdeNo ratings yet

- House of Mango Street - Han Jade NgoDocument2 pagesHouse of Mango Street - Han Jade Ngoapi-330328331No ratings yet

- Meezan BankDocument40 pagesMeezan BankShahid Abdul100% (1)

- Cymar International, Inc. v. Farling Industrial Co., Ltd.Document29 pagesCymar International, Inc. v. Farling Industrial Co., Ltd.Shienna Divina GordoNo ratings yet

- Dealey Field Day 10 FlyerDocument1 pageDealey Field Day 10 FlyercooperrebeccaNo ratings yet

- GSCR Report China KoreaDocument313 pagesGSCR Report China KoreaD.j. DXNo ratings yet

- Sap Erp Integration of Business ProcessesDocument4 pagesSap Erp Integration of Business ProcessesShaik Shoeb AbdullahNo ratings yet

- New Ford Endeavour Brochure Mobile PDFDocument13 pagesNew Ford Endeavour Brochure Mobile PDFAnurag JhaNo ratings yet

- Reading Report G9Document50 pagesReading Report G9Grade9 2023No ratings yet

- TNB Electricity System Voltages, Frequencies, Earthing Systems and Supply OptionsDocument4 pagesTNB Electricity System Voltages, Frequencies, Earthing Systems and Supply OptionsSaiful RizamNo ratings yet

- Sri Aurobindo's Guidance on Sadhana and the MindDocument8 pagesSri Aurobindo's Guidance on Sadhana and the MindShiyama SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- Mindmap: English Grade 5Document19 pagesMindmap: English Grade 5Phương HoàngNo ratings yet

- Darwin Route10 Pocket Maps/TimetableDocument2 pagesDarwin Route10 Pocket Maps/TimetableLachlanNo ratings yet

- An Inscribed Nabataean Bronze Object DedDocument15 pagesAn Inscribed Nabataean Bronze Object Dedejc1717No ratings yet

- Au L 1637113412 Poem Analysis of Matilda by Hilaire Belloc - Ver - 2Document5 pagesAu L 1637113412 Poem Analysis of Matilda by Hilaire Belloc - Ver - 2Manha abdellahNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Template: DirectionsDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Template: Directionsapi-612420884No ratings yet

- Romblon Site Evaluation WorksheetDocument4 pagesRomblon Site Evaluation WorksheetMariel TrinidadNo ratings yet