Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Andean Cat

Andean Cat

Uploaded by

Klaudia SíposOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Andean Cat

Andean Cat

Uploaded by

Klaudia SíposCopyright:

Available Formats

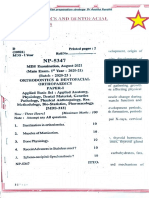

Journal of Mammalogy, 83(1):110–124, 2002

ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CAT, OREAILURUS JACOBITA:

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION AND COMPARISON WITH

OTHER FELINES FROM THE ALTIPLANO

ROSA GARCı́A-PEREA*

Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CL. J. Gutierrez Abascal 2, Madrid 28006, Spain

Recent field surveys searching for the rare Andean mountain cat, Oreailurus jacobita, have

had difficulty in identifying this species from sightings and skins. This is caused by the

paucity of museum specimens (only 3 skulls available to date) and the lack of criteria to

differentiate this species from other small sympatric felines (e.g., Lynchailurus pajeros). In

a study to solve these problems, 3 new skulls of O. jacobita were identified and a total of

5 skulls and 41 skins examined. Skulls of O. jacobita average 12–14% larger than skulls

of L. pajeros, showing a large anterior chamber in the bulla. Andean mountain cats have

vertical series of yellowish-brown blotches on the sides, and a long, bushy tail with wide

dark rings. Two keys to differentiate these felines, based on these and other characters, are

offered.

Key words: Andean altiplano, Andean mountain cat, feral cat, Lynchailurus pajeros, morphological

keys, Oreailurus jacobita, pampas cat, South America

Two species of small wild cat occur in been made. Also, age and sex variations are

and around the Andean altiplano of Peru, unknown.

Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina: Andean The pampas cat has traditionally been

mountain cat (Oreailurus jacobita Cornalia, considered a unique, polymorphic species

1865) and pampas cat (Lynchailurus pajer- (Lynchailurus pajeros, after Allen 1919, or

os (Desmarest, 1816)). The 1st species is a Oncifelis colocolo, after Wozencraft 1993),

poorly known felid, whose morphology and although it has recently been split into 3

biometry have been poorly described on the species (Garcı́a-Perea 1994): Lynchailurus

basis of 3 skulls (Kuhn 1973; Pearson pajeros, L. colocolo, and L. braccatus. The

1957; Philippi 1870), 14 skins (Burmeister amount and nature of morphological vari-

1879; Cabrera 1961; Cornalia 1865; Greer ation within this species group have been

1965; Matschie 1912; Philippi 1870, 1873; described in some detail by Garcı́a-Perea

Pine et al. 1979; Pocock 1941; Scrocchi and (1994).

Halloy 1986; Yepes 1929), and photographs No museum specimens of the pampas cat

of 3 individuals in their natural habitat from the altiplano were found by Garcı́a-

(Sanderson 1999; Scrocchi and Halloy Perea (1994), but recent reports indicate

1986; Ziesler 1992). Moreover, the 3 skulls that altiplano farmers keep skins of both

were subadult specimens, and 1 of them kinds of cat in their homes (A. Iriarte, L.

was lost at the beginning of the 20th cen- Villalba, and N. Bernal, in litt.). Although

tury. Based on such a small sample, no at- recent molecular studies (Johnson et al.

tempt at a detailed description of the mor- 1998) suggest that Oreailurus and Lyn-

phology and biometry of this species has chailurus are not closely related genera,

specimens of both genera can be confused

* Correspondent: mcng310@mncn.csic.es in altiplanic areas because of the external

110

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 111

similarity in their coat patterns. Native

farmers even give them the same name in

many localities (L. Villalba and N. Bernal,

in litt.). Field researchers have found it dif-

ficult to distinguish the 2 species in sight-

ings, skins stuffed by native people, or

skulls found occasionally while conducting

fieldwork. For example, some of the Boli-

vian records of O. jacobita included in Yen-

sen et al. (1994) belong to L. pajeros (see

‘‘Conclusions’’). This situation is caused by

the paucity of museum specimens of O. ja-

cobita available for comparative purposes FIG. 1.—A) Dorsal view of subadult skull of

and the lack of published information pro- Oreailurus jacobita (based on MVZ 116317)

viding field researchers with effective tools showing an unossified interparietal bone (IB)

to identify specimens. and a developing sagittal crest (SC). B) Ventral

Awareness of these difficulties led me to view of a juvenile skull of Lynchailurus pajeros

conduct a study focused on providing a key (based on CBF 2960) showing upper milk den-

for differentiating small wild cats living in tition (dC, dP3, dP4) and unossified sphenooc-

cipital synchondrosis (SS).

the area. The goals of my study were char-

acterization of external and skull morphol-

ogies of O. jacobita and elaboration of a Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. Specimens

key for differentiating altiplanic individuals were identified to species a priori by skull and

of the Andean mountain cat and the pampas skin characters, based on the information pro-

cat. I have included, wherever possible, vided by the few descriptive papers available

some comparisons with the domestic cat (e.g., Cabrera 1961; Garcı́a-Perea 1994) and my

(Felis catus), because feral specimens of own data. Only specimens of pampas cats from

the domestic form of the African wild cat the altiplano and nearby areas were considered,

(Felis silvestris lybica group, after Nowell in order to remove geographic variation from the

and Jackson 1996) seem to be widespread sample (Garcı́a-Perea 1994).

in the altiplano and other remote places of For morphological characterization of O. ja-

cobita and for purposes of comparison among

South America. However, the high amount

species, a relative age was assigned to each in-

of variation in skull and pelage character- dividual. Age was estimated on skulls based on

istics of these feral specimens makes it im- the developmental stages of several morpholog-

possible to treat these differences in depth ical structures (Barone 1976; Garcı́a-Perea 1991,

now. A recent revision of the information 1996; Garcı́a-Perea et al. 1996; Gaunt 1959). Ju-

available on O. jacobita, based on litera- veniles (1st year) can be identified as those hav-

ture, has been released (Yensen and Sey- ing deciduous dentition either erupting, fully

mour 2000). In this article, I am providing erupted, or being replaced by permanent teeth

firsthand data from the largest sample ever (Fig. 1B), and as those lacking sagittal crest or

studied of the rare Andean mountain cat. showing only an incipient structure. Subadults

(2nd year) can be identified as those having per-

MATERIALS AND METHODS manent dentition, unossified sphenooccipital

synchondrosis, and interparietal bone, and a de-

A sample of 44 specimens (3 skulls, 39 skins, veloping sagittal crest (Fig. 1A). Adults are

and 2 skulls plus skins) of O. jacobita, 50 spec- specimens more than 2 years old, showing to-

imens (29 skulls and 38 skins) of L. pajeros, and tally ossified sphenooccipital synchondrosis and

16 specimens (15 skulls and 6 skins) of F. catus interparietal bone. The word adult is used here

kept in 14 American and European institutions with an ontogenetic meaning, indicating that

was studied (Appendix I). Specimens were from specimens have ended their growth and have

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

112 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

reached their definitive physical characteristics using a digital caliper accurate to 0.02 mm. De-

(i.e., not related to reproductive condition). scriptive statistics (mean, standard error of

Skulls were classified by age as follows: O. ja- mean, range) were calculated for each variable.

cobita, 2 subadults and 3 adults; L. pajeros, 5 Because I had only 2 subadult and 3 adult spec-

juveniles, 5 subadults, and 19 adults; and F. ca- imens of O. jacobita, no statistical tests were

tus, 15 adults. applied to test differences observed between the

No criteria have been established for estimat- 2 age groups. However, significant differences

ing age from felid skins except relative size, to have been found between subadults and adults

use which we need to know already the size of of other felid species (Andersen and Wiig 1984;

adult specimens, and this was not the case for Garcı́a-Perea et al. 1996); so differences among

the Andean mountain cat. However, the large species were tested only on adult specimens.

sample (n 5 20) of O. jacobita skins studied Thus, the sample used for that purpose consisted

from Catamarca, Argentina, offered a unique op- of 3 O. jacobita, 19 L. pajeros, and 14 F. catus

portunity to analyze age variation. Considering (craniometric data of F. catus were recorded

the fact that these specimens came from a rela- from literature—Pocock 1951—because only

tively small area, I assumed that they represent- qualitative characters were available from the 15

ed a single population. All skins were preserved skulls mentioned earlier). For dental measure-

with the same tanning method, so I assumed that ments, 5 skulls of O. jacobita were considered,

size differences I observed reflected real differ- because carnassials erupt with their definitive di-

ences in size between individuals. Five external mensions. Differences among pairs of species

measurements were recorded wherever avail- were tested by Mann–Whitney U-test and Stu-

able, either from the collection labels or from dent’s t-test, using SPSS software (SPSS Inc.

measurement of specimens of O. jacobita: head 1993).

and body length, tail length, hind foot length, Further, 119 morphological characters were

ear length, and body weight. checked on each skull to record the character

Based on these premises, I used the variables states present in the sample, but only 10 of them

head and body length and tail length on the showed variation when specimens of Oreailurus

skins, searching for differences in global size and Lynchailurus were compared (Figs. 3–5):

that could be attributed to age. A comparison of palate—position of anterior palatine foramina

values obtained allowed me to establish 3 size relative to palatine-maxilla suture; rostrum—

classes. Because males are likely larger than fe- shape of nasal bones; zygomatic arches—size of

males, as in most felids (Garcı́a-Perea 1994, dorsal postorbital process of jugal; basicran-

1996, in litt.; Garcı́a-Perea et al. 1985), some ium—shape of presphenoid body; bullae—po-

differences in size could be attributed to sexual sition of vagina processus hyoideus relative to

dimorphism. However, the 3 size groups identi- stylomastoid foramen; bullae—shape of paroc-

fied showed noticeable differences in spotting cipital processes; teeth—1 ridge between 2

pattern and color, something unusual among grooves in lingual side of upper canine; teeth—

males and females of the same species of wild size of parastyle related to protocone of P4;

felid but linked to growth in many species such teeth—metaconid on m1; and bullae—relative

as the lion, the cougar, or the lynx (Ewer 1973; size of ecto- and entotympanic chambers.

R. Garcı́a-Perea, in litt.). I assumed therefore Seven characters related to body proportions,

that the 3 size groups represented 3 age classes, external anatomy, and coat pattern were exam-

covering age periods perhaps not strictly equiv- ined on each skin wherever possible (Figs. 6 and

alent to those described based on skull (values 7): legs—black, conspicuous rings around fore-

of head and body length and tail length in mil- arms; ears—color of dorsal region; body—spi-

limeters): juveniles (n 5 1, head and body length nal crest (band of long, erectile fur from shoul-

5 500, tail length about 330); subadults (n 5 8, ders to base of tail); body—arrangement and

head and body length 5 640–660, tail length 5 color of blotches or rosettes on sides; face—col-

330–420); and adults (n 5 11, head and body or of rhinarium; tail—number, size, and color of

length 5 740–850, tail length 5 410–480). rings; and tail length—percentage of head and

Twenty skull and teeth variables commonly body length represented.

used for carnivores were measured on each A Spanish summary of the results is available

specimen of O. jacobita and L. pajeros (Fig. 2), at the web site of Cat Action Treasury (CAT),

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 113

FIG. 2.—Variables measured on each skull. P4, m1: upper and lower carnassials, respectively, in

occlusal views. GLS—greatest length of skull, CBL—condylobasal length, BAL—basilar axis length,

ZW—zygomatic width, PL—palatal length, FW—facial width (distance between tips of postorbital

processes), IOW—interorbital width, POW—postorbital width, CH—neurocranial height, RL—ros-

tral length, IBD—interbullae distance, MW—mastoid width, RWC—rostral width across the canines,

SCL—sagittal crest length, ML—mandible length, MRH—height of mandible ramus, P4L—length

of upper P4, P4W—maximum width of P4, Lm1—length of lower m1, Wm1—maximum width of m1.

www.felidae.org. Spanish translations of figure strictions of adults are narrower (lower val-

legends and titles of tables are available from ues of postorbital width). These results are

the author. consistent with those found for other felid

species, such as the Lynx (Andersen and

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Wiig 1984; Garcı́a-Perea 1991) and other

Age-related variation in skulls of O. ja- carnivores (e.g., Genetta genetta—Craw-

cobita.—The youngest specimens of this ford-Cabral 1981).

species studied were 2 subadults (MVZ These ontogenetic changes must be con-

116317, UG D2337). Besides the small size sidered carefully, because several characters

compared with adults (Table 1) and an un- described by Pocock (1941) and Cabrera

ossified sphenooccipital synchondrosis (1940, 1961) to differentiate Oreailurus

(Fig. 1A), subadults have different skull (Colocolo after Pocock) from Lynchailurus

proportions: postorbital processes are less and other South American felids showed

developed, zygomatic arches are narrower, age-related variation, and the skull of O. ja-

and sagittal crest is shorter (i.e., lower val- cobita they based their results on was a sub-

ues of facial width, zygomatic width, and adult (Philippi 1873). For example, Cabrera

sagittal crest length). Also, postorbital con- (1961:203) described the sagittal crest of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

114 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

FIG. 4.—Qualitative characters and propor-

tions differing in skulls of A) Felis catus, B)

Oreailurus jacobita, and C) Lynchailurus pajer-

os. EC: ectotympanic chamber of bulla, EN: en-

totympanic chamber of bulla, PPJ: postorbital

process of jugal, PP: paroccipital process, P2:

upper 2nd premolar. Black arrows highlight cer-

tain anatomical differences mentioned in text.

from the ventral parts, which are chocolate

over a creamy background. Markings from

the sides are rosette-like, reddish-brown in-

side with darker borders. Tail rings are nar-

FIG. 3.—Qualitative characters and propor- rower, closer to each other, and darker

tions differing in skulls of A) and B) Oreailurus brown than those of adults. Head is gray,

jacobita and C) and D) Lynchailurus pajeros. as in adults, but also darker. Black markings

NB: nasal bones, SC: sagittal crest, PB: pre- on front legs are more conspicuous in the

sphenoid body, EC: ectotympanic chamber of kitten, but not forming rings.

bulla, EN: entotympanic chamber of bulla, APF: In subadults, the general color becomes

anterior palatine foramina, C: upper canine, P3: lighter. Compared with adults, the ground

3rd upper premolar, P4: upper carnassial, M1:

color is creamy instead of gray, and blotch-

1st upper molar.

es look reddish. As in the juvenile, blotches

are smaller and more numerous in subadults

Oreailurus as ‘‘only well developed in its than in adults and are distributed irregular-

occipital tip,’’ and this is true for all sub- ly. There is a blackish band along the back

adults and 1 adult of small skull size (nonerectile), lacking the reddish tinge of

(MUSM 6015), but not for 2 other adults that in adults. Some subadults show con-

(CBF 445, CGECM 027), which have long spicuous black markings on the front legs,

sagittal crests. It must be noted that values but these never form rings. Belly spots are

of sagittal crest length increase with age in darker than those of adults. Tail rings are

other felids, sometimes remarkably so, and more like those of adults than those of the

that sagittal crest length is positively cor- juvenile, but still narrower.

related with skull size (Garcı́a-Perea 1996). From the previous descriptions, data pre-

Age-related variation in skins of O. ja- viously published (Garcı́a-Perea 1994), and

cobita.—The only juvenile examined information provided subsequently (under

(MACN 37.34) had a higher number of ‘‘Coat characteristics of O. jacobita’’), it

blotches, smaller than those of adults and follows that subadults of O. jacobita could

of markedly darker color, especially those be mistaken for adult Lynchailurus from the

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 115

FIG. 7.—Main external differences observed

between A) Oreailurus jacobita and B) Lyn-

FIG. 5.—Qualitative differences between up- chailurus pajeros from the altiplano. Black ar-

per carnassials (P4) of A) Lynchailurus pajeros rows indicate characters differentiating the 2

and B) Oreailurus jacobita. Pr: protocone, Pa: species.

parastyle, Ec: ectostyle.

ual dimorphism of this species. However,

altiplano (especially in sightings), unless the relatively small size of specimen

the details of tail rings, front leg stripes, and MUSM 6015, an old adult with totally os-

spinal crest are identified. sified sutures and rough braincase surface

Skull and body measurements of O. ja- (Table 1), suggests that MUSM 6015 could

cobita.—Values for skull and teeth variables be a female. This pattern of females being

measured on specimens of O. jacobita are smaller than males occurs in other felid spe-

summarized in Table 1. Because the only cies (e.g., Lynx pardinus—Garcı́a-Perea et

skull of known sex studied was a male (Ta- al. 1985).

ble 1), it is risky to say anything about sex- Data suggest that, although some large

FIG. 6.—External appearance of adult Oreailurus jacobita. Based on pictures of a living individual

and on museum specimens (see Appendix I).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

116 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

TABLE 1.—Values (in millimeters) of 20 skull and teeth variables measured on 2 subadult and 3

adult specimens of O. jacobita. Sex is indicated where known. Additional data from 1 skull from

the literature are included. Specimen numbers refer to museums listed in Appendix I.

MVZ UG MUSM CBF CGECM From

Variable 116317 D2337 6015 445 027 literaturea

Age class Subadult Subadult Adult Adult Adult Subadult

Sex Male

Greatest length of skull 99.9 104.4 100.4 114.8 108.4 105.0

Condylobasal length 95.8 98.2 94.4 107.3 102.6 99.0

Rostral length 34.8 37.0 35.0 37.2 37.2

Rostral width across

the canines 24.8 25.0 24.8 27.3

Mastoid width 45.9 47.7 44.8 47.3

Palatal length 38.1 40.2 38.5 44.7 43.5

Interorbital width 20.6 23.2 23.8 26.7 24.1

Facial width 41.8 46.3 48.1 51.2 47.1

Postorbital width 29.0 29.9 29.1 28.4 25.9

Zygomatic width 69.1 72.9 71.2 79.7 78.5 71.0

Basilar axis length 33.8 33.5 31.7 35.3

Neurocranial height 34.9 35.5 36.0 38.4 35.6

Interbullae distance 15.0 12.8 13.5 13.0 13.5

Sagittal crest length 6.7 11.8 10.8 43.5 43.7

Length of P4 13.9 13.2 12.8 14.0 12.5 14.0

Maximum width of P4 7.1 6.9 6.9 7.2 7.1

Mandible length 66.9 70.2 65.1 75.5 72.6

Height of mandible ramus 29.6 30.6 28.7 34.2 34.4

Length of ml 11.0 10.3 9.8 11.4 11.3

Maximum width of ml 4.6 4.5 4.5 4.7 5.0

a

Skull illustrated by Philippi (1873) and measured by Cabrera (1961).

specimens of the pampas cat have skull di- and more flat in O. jacobita than in L. pa-

mensions similar to those of O. jacobita, jeros; adult specimens of O. jacobita usu-

the latter species is significantly larger ally show a long sagittal crest, which is

(greatest length of skull 12% larger, con- never so well developed in adult specimens

dylobasal length 14% larger) than altiplanic of L. pajeros from the altiplano; and audi-

specimens of L. pajeros and F. catus (great- tory bullae are relatively smaller and more

est length of skull 19% larger, condylobasal separate in O. jacobita (Figs. 3 and 4) than

length 21% larger; Table 2). Carnassial in L. pajeros (interbullae distance; Table 2).

teeth (P4 and m1) are also significantly An elongated muzzle places postorbital pro-

more massive in O. jacobita than in L. pa- cesses of O. jacobita closer to the middle

jeros and in F. catus (P4 length, m1 length; of the skull (Figs. 3A and 4B), as Yensen

Table 2). Note that average values and rang- and Seymour (2000) mention, but not as

es of skull measurements of adult O. jacob- much as Pocock (1941) indicates. As I not-

ita given in Table 2 are larger that those ed above, Pocock and Cabrera based their

offered by Yensen and Seymour (2000:2), descriptions on the subadult specimen illus-

because their sample included subadult trated by Philippi (1873).

specimens. Values of external measurements ob-

Observation of skulls also shows other tained on tanned skins from Catamarca

differences: dorsal profile of skull is more were useful for establishing age classes, but

flat and elongated in O. jacobita than in L. they could not be used for descriptive pur-

pajeros; dorsal profile of rostrum is lower poses because they were likely overesti-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 117

mated. In fact, specimen MVZ 116317 general view of an adult O. jacobita show-

(Pearson 1957), a subadult male, shows ing the most conspicuous features charac-

lower values of body measurements (on the terizing the coat pattern of this species is

flesh) than those measured on subadult Ca- shown in Fig. 6—based on photographs of

tamarca specimens (Table 3). These differ- living individuals and on museum study

ences are likely a consequence of change in skins. Former illustrations of O. jacobita

size due to the tanning method. Average shown by Cabrera and Yepes (1940:plate

values given by Yensen and Seymour 29), by Seidensticker and Lumpkin (1991:

(2000), based on the five specimens record- 48), and by Redford and Eisenberg (1992:

ed in the literature (also given in Table 3), plate 9h) fail to reflect accurately external

are just suggestive, because age of speci- characters such as shape and distribution of

mens is unknown, except for 1 subadult, body markings, tail proportions, and tail

and subadult felids are significantly smaller rings of the species.

than adults (e.g., Garcı́a-Perea 1996; The ground color of an adult O. jacobita

Garcı́a-Perea et al. 1996). is ashy-gray, with yellowish-brown, irreg-

Regarding the 10 qualitative traits show- ular blotches arranged in vertical series on

ing variation in skulls of O. jacobita and L. the flanks (transverse lines, when observed

pajeros, character states observed on the from the top). The head and face are gray,

sample are shown in Table 4. These char- with cheeks and areas around the lips white.

acters confirm that, as Kuhn (1973) men- As in many other felids, 2 dark brown lines

tioned, the relative sizes of ecto- and ento- run across the cheeks, converging laterally.

tympanic chambers of auditory bulla are di- In some specimens, 2 dark gray lines start

agnostic for O. jacobita in the altiplano, not above the eyes, running up to the space be-

the presence of external groove, or sulcus, tween the ears. From there, 2 wide yellow-

separating both chambers (Pocock 1941), ish-brown bars run laterally down to the

which is not always obvious, as the sulcus base of the neck, sometimes with 1 or 2

bars of the same color between them. Ears

does not appear better developed in all old

are gray, with darker borders. There is a

individuals, as Seymour (1999) claims. In

rusty-black band (nonerectile fur) along the

O. jacobita, the ectotympanic chamber is

back. Some black spots occur in the ulnar

equal to or larger than the entotympanic

region of forelegs, but never forming com-

(Table 4), representing more than 50% of

plete rings like those in L. pajeros. How-

bullar volume. However, this character is

ever, hind limbs may have 1 or 2 narrow,

not unique to O. jacobita, because L. colo- dark rings, dorsally black and ventrally red-

colo from central Chile, and some species dish. Belly is white or creamy with light

of Felis (e.g., F. manul, F. margarita) also brown spots laterally and black spots me-

have an ectotympanic chamber equal to or dially. One or 2 dark brown, transverse

larger than the entotympanic chamber stripes occur in the ventral part of the neck,

(Garcı́a-Perea 1994; Pocock 1916). sometimes incomplete.

As Cabrera (1961) suspected, the 5 skulls Tail is long (around 66–75% of head and

of O. jacobita lack P2 (similar to L. paje- body length in fresh specimens), bushy, and

ros). Its dental formula is then I 3/3, C 1/ cylindrical, showing 6–9 rings varying

1, P 2/2, M 1/1, total 28. from black to dark brown. The 3 or 4 distal

Feral cats show a high amount of varia- rings are remarkably wider (up to 60 mm

tion in qualitative characters of skull. For wide) than those of the proximal half.

this reason, I am providing in Table 5 some Two adult females had well-developed

typical, although not exclusive, skull char- mammae with no fur around them, sug-

acters that, if restricted to the altiplano, can gesting that they were rearing kittens when

help to identify F. catus (Fig. 4A). captured. Both females had 2 pairs of mam-

Coat characteristics of O. jacobita.—A mae located in abdominal position, and

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

118 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

TABLE 2.—Descriptive statistics for 20 cranial variables of adult O. jacobita and L. pajeros and

of 8 variables of adult F. catus (after Pocock 1951); n 5 sample size. Level of significance is indicated

for Mann–Whitney U-test (comparing O. jacobita with each of the other species) and Student’s t-

test (comparing L. pajeros with F. catus). Symbols: *, P # 0.05; **, P # 0.005; and ***, P # 0.001;

ns, not significant (P . 0.05).

Skull size (mm)

n X̄ SE Range L. pajeros F. catus

Greatest length of skull

O. jacobita 3 107.9 4.165 100.4—114.8 * **

L. pajeros 19 96.6 0.795 89.2—103.2 **

F. catus 14 90.9 1.734 81.0—99.0

Condylobasal length

O. jacobita 3 101.4 3.769 94.4—107.3 ** **

L. pajeros 19 89.0 0.690 82.3—94.4 **

F. catus 14 83.8 1.726 73.0—92.0

Rostral length

O. jacobita 3 36.5 0.733 35.0—37.2 ns

L. pajeros 19 32.9 0.447 29.1—37.0

Rostral width across the canines

O. jacobita 2 26.1 1.250 24.8—27.3 ns

L. pajeros 19 23.4 0.439 20.3—28.9

Mastoid width

O. jacobita 2 46.1 1.250 44.8—47.3 *

L. pajeros 19 41.8 0.418 38.9—45.6

Palatal length

O. jacobita 3 42.2 1.899 38.5—44.7 **

L. pajeros 18 34.7 0.388 31.3—37.7

Interorbital width

O. jacobita 3 24.9 0.921 23.8—26.7 ** **

L. pajeros 19 18.4 0.258 16.6—21.0 *

F. catus 14 17.2 0.422 15.0—19.0

Facial width

O. jacobita 3 48.8 1.234 47.1—51.2 *

L. pajeros 19 44.4 0.576 38.5—47.6

Postorbital width

O. jacobita 3 27.8 0.971 25.9—29.1 ns ns

L. pajeros 19 27.7 0.320 25.2—30.2 ***

F. catus 14 31.1 0.601 27.0—34.0

Zygomatic width

O. jacobita 3 76.5 2.656 71.2—79.7 * *

L. pajeros 17 68.7 0.859 60.1—73.3 ns

F. catus 14 65.1 1.664 56.0—73.0

Basilar axis length

O. jacobita 2 33.5 1.800 31.7—35.3 ns

L. pajeros 19 31.5 0.349 29.1—34.3

Neurocranical height

O. jacobita 3 36.7 0.874 35.6—38.4 ns

L. pajeros 19 36.5 0.349 34.4—40.3

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 119

TABLE 2.—Continued.

Skull size (mm)

n X̄ SE Range L. pajeros F. catus

Inter-bullar distance

O. jacobita 3 13.3 0.167 13.0—13.5 **

L. pajeros 19 11.0 0.228 9.1—12.8

Sagittal crest length

O. jacobita 3 32.7 10.933 10.8—43.7 ns

L. pajeros 19 18.5 1.176 10.0—29.6

Length of P4

O. jacobita 5 13.2 0.296 12.5—14.0 *** ***

L. pajeros 19 11.6 0.104 11.0—12.6 ***

F. catus 14 10.1 0.152 9.0—11.0

Maximum width of P4

O. jacobita 5 7.0 0.060 6.9—7.2 ***

L. pajeros 19 5.5 0.086 4.6—6.2

Mandible length

O. jacobita 3 71.1 3.099 65.1—75.5 ** *

L. pajeros 18 61.8 0.695 54.2—65.5 ns

F. catus 14 60.5 1.455 51.0—66.0

Height of ramus of mandible

O. jacobita 3 32.4 1.868 28.7—34.4 ns

L. pajeros 19 27.8 0.505 21.6—30.9

Length of ml

O. jacobita 5 10.8 0.308 9.8—11.4 *** ***

L. pajeros 11 9.1 0.132 8.3—9.6 ***

F. catus 14 7.5 0.111 7.0—8.0

Maximum width of ml

O. jacobita 5 4.7 0.093 4.5—5.0 ***

L. pajeros 11 4.1 0.060 3.8—4.4

both were captured in December. Taking Regarding O. jacobita, data recorded from

into account that weaning usually occurs in literature (fresh specimens, n 5 5), indicate

small felids about 2 months after birth that its tail length is about 66–75% of head

(Ewer 1973; Kitchener 1991), birth of both and body length, whereas data recorded

litters could have occurred around October, from collection specimens (n 5 11) give a

during austral spring. figure of 52–65%. Similarly, data on fresh

Pelage of both O. jacobita and L. pajeros specimens of L. pajeros recorded from

differ conspicuously in 7 external charac- specimen labels (n 5 9) indicate that tail

ters, illustrated in Fig. 7 and described in length is about 40–50% of head and body

Table 4. Characteristics described are con- length, whereas these variables measured

sistent with those observed by L. Villalba on collection specimens yield values that

and N. Bernal (in litt.) are 34–38% of the length (n 5 9). My data

Tail of L. pajeros is shorter than that of on fresh specimens of O. jacobita agree

O. jacobita. It is necessary to be careful with those given by Yensen and Seymour

when checking tail proportions, because (2000)—60–75% of length—but data on L.

measurements taken on fresh specimens pajeros given by these authors (ca. 30%)

differ from those taken on collection skins. seem to refer to collection specimens.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

120 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

TABLE 3.—Values of 5 external measurements for O. jacobita, either found in the literature or measured on tanned collection skins for this

A great amount of variation is observed

Pine et al. 1979

in coat pattern of feral cats, too large to be

Matschie 1912

Cornalia 1865

Pearson 1957a

Cabrera 1961

Reference

treated here. However, I include in Table 5

This study

This study

the most striking characters of feral cats to

be considered when comparing with the 2

other wild genera, Oreailurus and Lynchail-

urus, occurring in the altiplanic area.

Body weight

CONCLUSIONS

4000

(g)

Felids are especially difficult to assess

morphologically. Usually, individual varia-

tion is moderate, and often odd character

states are found at very low frequencies. For

Length of

hind foot

this reason, finding diagnostic characters for

(mm)

133

110

115

closely related species is very difficult, and

it is safer to look for sets of traits character-

istic of a species, with a high probability of

finding them all together. Based on this pre-

Ear length

mise, a dichotomous key alone would not be

(mm)

63

53

enough for my purposes; so I am providing

sets of characters (Tables 4 and 5) that are

likely to occur together in a species, and if

one fails, we can confirm our identification

Tail length

330–420

410–485

by looking for a match with the others. From

(mm)

my experience, 1 or 2 characters are ex-

413

430

410

480

480

pected to be missing together. For F. catus,

only typical characters are provided, but we

must remember that they are not exclusive

body length

to F. catus and may not be present in some

Head and

640–660

740–850

(mm)

specimens. The following keys are only use-

ful within the limits of the altiplanic region,

577

600

850

640

640

because L. pajeros shows a certain amount

of geographic variation.

Key for skulls.—It is necessary to deter-

1

1

1

1

1

8

11

n

mine first whether the skull is from an adult

(with sphenooccipital synchondrosis ossi-

fied). If it is not, the key may not be useful.

After using the following keys, confirm

Subadult

Subadult

Age

identification using characters in Tables 4

Adult

Adult

and 5, especially for individuals with con-

study. n 5 sample size.

dylobasal length close to 94 mm (as certain

domestic cats could also have similar con-

Males and females

Males and females

dylobasal length).

MVZ 116317.

DICHOTOMOUS KEY FOR SKULLS

Sex

1a. Condylobasal length . 94 mm, lower

m1 length . 9.8 mm, dorsal profile of

Male

Male

skull flat and low, anterior chamber of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 121

TABLE 4.—Character states observed on skulls of O. jacobita and L. pajeros, and external traits

characterizing skins of both species.

Characters Oreailurus jacobita Lynchailurs pajeros

Skull

Location of anterior palatine At palatine-maxilla suture Posterior to palatine-maxilla suture

foramina

Shape of nasal bones Slowly narrowing posteriorly Strongly narrowing posterior half

Length of postorbital process of Short Long

jugal

Shape of body of presphenoid Widened medially No medial widening

Position of vagina processus hy- Posterior to stylomastoid foramen Medial to stylomastoid foramen

oideus

Shape of paroccipital processes Long, separate, protruding Short, not protruding, cupped

ventrally around bulla

Presence of lingual ridge in up- Absent Present

per canine

Relative size of parastyle and About the same size Larger than protocone or no proto-

protocone of P4 cone

Presence of metaconid on m1 Present (80%) Absent

Relative size of ectotympanic and Ectotympanic equal to or larger Ectotympanic smaller

entotympanic

Skin

Black rings on forelegs Absent, only large spots Present, complete rings

Color of ears dorsally Uniformly gray Black and cream and reddish

Spinal crest of erectile fur Absent Present

Pattern and color of body mark- Vertical series of yellowish-brown Oblique series or rusty rosettes

ings blotches

Color of rhinarium Black Pink to coffee or dark mahogany

Tail rings 6–9 dark brown-to-black rings, Around 8 reddish rings, up to 20

some of them reaching up to 60 mm wide each

mm wide

Tail length as percentage of head Tail length about 66–75% of head Tail length about 40–50% of head

and body length and body length and body length

bulla equal to or larger than posterior mend checking characters in Tables 4 and

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . O. jacobita 5 carefully.

1b. Condylobasal length # 94 mm, lower

m1 length , 9.6, dorsal profile high and DICHOTOMOUS KEY FOR SKINS

convex, anterior chamber of bulla small- 1a. Medium-sized body; tail length around

er than posterior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 66–75% of head and body length; no

2a. Presence of lingual ridges on upper ca- spinal crest; no complete rings in fore-

nines, lower m1 length . 8.0 mm, an- legs; body sides with blotches arranged

terior chamber of bulla medially ex- in vertical series . . . . . . . . . . . O. jacobita

panded and inflated . . . . . . . . . . L. pajeros 1b. Small-sized body; tail length ,50% of

2b. Absence of ridges on upper canines, head and body length; spinal crest pre-

lower m1 length , 8.0 mm, anterior

sent; complete rings in forelegs; body

chamber of bulla medially expanded but

sides not marked or with rosettes ar-

not inflated . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . F. catus

ranged in oblique series . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Dichotomous key for skins.—Because of 2a. Ears black and cream and reddish; body

the high amount of variation exhibited by sides with rusty rosettes arranged in

feral cats, this key may not be as effective oblique series . . . . . . . . . . . . . . L. pajeros

as the previous one for skulls; so I recom- 2b. Ears uniformly colored; body sides not

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

122 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

TABLE 5.—Skull and skin characters typical of ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F. catus, absent in O. jacobita and L. pajeros.

K. Nowell (Director, Cat Action Treasury)

Skull characters and P. Jackson (former Chairman, Cat Specialist

P2 present Group, IUCN) gave me the opportunity to con-

Unossified interparietal bone in adults duct this study. Funding was provided by Cat

Posterior border of palate W-shaped Action Treasury, supported by the Leonard X.

Ectotympanic expanded but no inflated Bosack and Bette M. Kruger Foundation. J. Gis-

Skin characters bert (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales,

Plain color, no body markings MNCN, Madrid) drew Figs. 1–5 and 7. M. An-

Medium-sized, slender tail, 2–5 black distal rings, tón drew Fig. 6, using pictures generously pro-

black tip vided by J. Sanderson. I am indebted to the peo-

Ears of reddish color, or another color matching ple in charge of the collections listed in Appen-

body dix I, who kindly provided access to them: E.

Vivar, N. Bernal, L. Villalba, M. Lucherini, E.

Luengos, J. L. Patton, H. J. Kuhn, A. Iriarte, J.

marked or with another pattern different Yañez, J. C. Torres-Mura, R. Kraft, M. Piantan-

from that described in 2a . . . . . . F. catus ida, O. Vaccaro, P. Jenkins, D. M. Hills, L. Gor-

don, M. Carleton, M. Rutzmosser, S. Anderson,

Based on skull and skin characteristics G. Musser, and B. Patterson. This study has also

described earlier and from a detailed com- benefited from grant DGICYT PB95-0114

parison with O. jacobita and L. pajeros ma- (Spain, 1999), a Large Scale Facilities grant un-

terials, specimens CBF 2224, CBF 2960, der the Training and Mobility of Researchers

and CBF 2229, previously identified as O. Programme (European Union, 1999), and from

jacobita (Yensen et al. 1994) were identi- a grant under the Agreement CSIC-Deutsche

fied as L. pajeros in this study. Forschungsgemeinschaft (Spain–Germany,

RESUMEN 1995). These funds were made available thanks

to J. Morales (MNCN, Madrid), P. Jenkins (The

Recientes expediciones en busca del des- Natural History Museum, London, United King-

conocido gato andino, Oreailurus jacobita, dom), and G. Peters (Museum Alexander Ko-

se han encontrado con dificultades para enig, Bonn, Germany). Valuable comments of an

identificar esta especie a partir de avista- anonymous reviewer improved this article.

mientos y pieles. Esto se debe a la escasez

de ejemplares en las colecciones (sólo se LITERATURE CITED

conocı́an 3 cráneos hasta ahora) y a la au- ALLEN, J. A. 1919. Notes on the synonymy and no-

menclature of the smaller spotted cats of tropical

sencia de criterios para diferenciar esta es- America. Bulletin of the American Museum of Nat-

pecie de otros felinos simpátricos (por ural History 41:341–419.

ejemplo, Lynchailurus pajeros). Con el ob- ANDERSEN, T., AND O. WIIG. 1984. Growth of the skull

of Norwegian lynx. Acta Theriologica 29:89–100.

jeto de resolver estos problemas, se ha reali- BARONE, R. 1976. Anatomie comparée des mammifèr-

zado un estudio en el que se han identifi- es domestiques. Tome I. Ostéologie. Fascicle 1

cado 3 nuevos cráneos de O. jacobita, ha- (texte). Vigot Frères, Paris, France.

BURMEISTER, H. 1879. Description physique de la Re-

biéndose examinado en total 5 cráneos y 41 públique Argentine. 3:1–126.

pieles. Los cráneos de O. jacobita son un CABRERA, A. 1940. Notas sobre carnı́voros sudameri-

12–14% más grandes que los de L. pajeros, canos. Notas del Museo de La Plata (Zoologia) 5:

1–22.

mostrando una gran cámara anterior en la CABRERA, A. 1961. Los félidos vivientes de la Repúb-

bula timpánica. El gato andino presenta se- lica Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de

ries verticales de manchas pardo-amarillen- Ciencias Naturales (Zoologia) 6:161–247.

CABRERA, A., AND J. YEPES. 1940. Historia natural

tas en los flancos, ası́ como una larga cola Ediar. Mamı́feros Sud-Americanos. Compañı́a Ar-

con abundante pelo y anchos anillos oscu- gentina de Editores, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

ros. Se ofrecen dos claves para diferenciar CORNALIA, E. 1865. Descrizione di una nuova specie

del genere Felis, Felis jacobita (Corn.). Memorie

estas especies de felinos basadas en estos y della Societá Italiana di Scienze Naturali 1:1–9.

otros caracteres. CRAWFORD-CABRAL, J. 1981. Análise de dados cran-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

February 2002 GARCÍA-PEREA—MORPHOLOGY OF ANDEAN MOUNTAIN CATS 123

iométricos no género Genetta G. Cuvier (Carnivora, POCOCK, R. I. 1951. Catalogue of the genus Felis. Brit-

Viverridae). Memórias da Junta de Investigações do ish Museum (Natural History), London, United

Ultramar 66:1–329. Kingdom.

EWER, R. F. 1973. The carnivores. Cornell University REDFORD, K. H., AND J. F. EISENBERG. 1992. Mammals

Press, New York. of the Neotropics. The southern cone: Chile, Argen-

GARCı́A-PEREA, R. 1991. Variabilidad morfológica del tina, Uruguay, Paraguay. University of Chicago

género Lynx Kerr, 1792 (Carnivora, Felidae). Ph.D. Press, Chicago, Illinois 2:1–430.

dissertation, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, SANDERSON, J. G. 1999. Andean mountain cats (Or-

Spain. eailurus jacobita) in northern Chile. Cat News 30:

GARCı́A-PEREA, R. 1994. The pampas cat group (Genus 25–26.

Lynchailurus Severtzov, 1858) (Carnivora: Felidae), SCROCCHI, G. J., AND S. P. HALLOY. 1986. Notas sis-

a systematic and biogeographic review. American temáticas, ecológicas, etológicas y biogeográficas

Museum Novitates 3096:1–36. sobre el gato andino, Felis jacobita Cornalia (Feli-

GARCı́A-PEREA, R. 1996. Patterns of postnatal devel- dae, Carnivora). Acta Zoologica Lilloana 38:157–

opment in skulls of lynxes, genus Lynx (Mammalia, 170.

Carnivora). Journal of Morphology 229:241–254. SEIDENSTICKER, J., AND S. LUMPKIN (EDS.). 1991. Great

GARCı́A-PEREA, R., R. BAQUERO, R. FERNÁNDEZ-SAL- cats. Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press,

VADOR, AND J. GISBERT. 1996. Desarrollo juvenil del Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

cráneo en las poblaciones ibéricas de gato montés, SEVERTZOW, M. N. 1858. Notice sur la classification

Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777. Doñana, Acta Ver- multisériale des carnivores, spécialement des félidés,

tebrata 23:153–164. et les études de zoologie générale qui s’y rattachent.

GARCı́A-PEREA, R., J. GISBERT, AND F. PALACIOS. 1985. Revue et Magazine de Zoologie, 2nd Series 10:385–

Review of the biometrical and morphological fea- 393.

tures of the skull of the Iberian Lynx, Lynx pardina SEYMOUR, K. L. 1999. Taxonomy, morphology, pale-

(Temminck, 1824). Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen ontology and phylogeny of the South American

32:249–259. small cats (Mammalia: Felidae). Ph.D. dissertation,

GAUNT, W. A. 1959. The development of the deciduous University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

cheek teeth of the cat. Acta Anatomica 38:187–212. SPSS INC. 1993. SPSS for Windows. Version 6.0.

GREER, J. K. 1965. Another record of the Andean high- SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois.

land cat from Chile. Journal of Mammalogy 46:507. WOZENCRAFT, C. W. 1993. Order Carnivora. Pp. 279–

JOHNSON, W. E., M. CULVER, J. A. IRIARTE, E. EIZIRIK, 348 in Mammal species of the world. (D. E. Wilson

K. L. SEYMOUR, AND S. J. O’BRIEN. 1998. Tracking and D. M. Reeder, eds.). 2nd ed. Smithsonian Insti-

the evolution of the elusive Andean Mountain cat tution Press, Washington, D.C.

(Oreailurus jacobita) from mitochondrial DNA. YENSEN, E., AND K. L. SEYMOUR. 2000. Oreailurus ja-

Journal of Heredity 89:227–232. cobita. Mammalian Species 644:1–6.

KITCHENER, A. 1991. The natural history of the wild YENSEN, E., T. TARIFA, AND S. ANDERSON. 1994. New

cats. Cornell University Press, New York. distributional records of some Bolivian mammals.

KUHN, H. J. 1973. Zur Kenntnis der Andenkatze, Felis Mammalia 58:405–413.

(Oreailurus) jacobita Cornalia, 1865. Säugetierkun- YEPES, J. 1929. Notas sobre algunos de los mamı́feros

dliche Mitteilungen 21:359–364. descriptos por Molina, con distribución geográfica

MATSCHIE, P. 1912. Über Felis jacobita, colocola und en Chile y Argentina. Revista Chilena de Historia

zwei ihnen ähnliche Katzen. Sitzungsberichten der Natural 33:468–472.

Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde (Berlin) 4: ZIESLER, G. 1992. Souvenir d’un chat des Andes. An-

255–259. iman, Nature et Civilisations 50:68–79.

NOWELL, K., AND P. JACKSON (EDS.). 1996. Wildcats,

status survey and conservation action plan. Cat Spe- Submitted 4 May 2000. Accepted 9 May 2001.

cialist Group (SSC, IUCN), Gland, Switzerland.

PEARSON, O. P. 1957. Additions to the mammalian fau- Associate Editor was Meredith J. Hamilton.

na of Peru and notes on some other Peruvian mam-

mals. Breviora 73:1–7. APPENDIX I

PHILIPPI, R. A. 1870. Ueber Felis colocolo Molina. Ar-

chiv für Naturgeschichte 36:41–45. Collections consulted for this study.—Ameri-

PHILIPPI, R. A. 1873. Ueber Felis guiña Molina und can Museum of Natural History, New York

über die Schädelbildung bei Felis pajeros und Felis (AMNH); The Natural History Museum, Lon-

colocolo. Archiv für Naturgeschichte 39:8–15. don, United Kingdom (BM); Colección Bolivi-

PINE, R. H., S. D. MILLER, AND M. L. SCHAMBERGER.

1979. Contributions to the mammalogy of Chile.

ana de Fauna, Mastozoologı́a, La Paz, Bolivia

Mammalia 43:339–376. (CBF); Collection of the Grupo de Ecologı́a

POCOCK, R. I. 1916. The structure of the auditory bulla Comportamental de Mamı́feros, Universidad

in existing species of Felidae. Annals and Magazine Nacional del Sur, Bahı́a Blanca, Argentina

of Natural History, Series 8 18:326–334. (CGECM); Field Museum of Natural History,

POCOCK, R. I. 1941. The examples of the Colocolo and

of the Pampas cat in the British Museum. Annals Chicago, Illinois (FMNH); Museo Argentino de

and Magazine of Natural History, Series 11 7:257– Ciencias Naturales, Buenos Aires, Argentine

274. (MACN); Museum of Comparative Zoology,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

124 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY Vol. 83, No. 1

Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 37.142; 37.143; 42.113; 9 uncataloged. MNHN:

(MCZ); Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, 1 uncataloged. MUSM: 6015; 1 uncataloged.

Santiago de Chile, Chile (MNHN); Museo de MVZ: 116317. SAG: 1 uncataloged. UG:

Historia Natural Javier Prado, Lima, Peru D2337. ZSM: 1984/12.

(MUSM); Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Uni- Lynchailurus pajeros.—BM: 26.5.3.6;

versity of California, Berkeley, California 27.11.1.66; 27.11.1.67; 34.9.2.31; 34.11.4.5;

(MVZ); Servicio Agrı́cola y Ganadero, Ministry 42.57. CBF: 02224; 02229; 02274; 02960;

of Agriculture, Chile (SAG); University of Got- 06142; 06144; 06145; 06146. CGECM: 001;

tingen, Gottingen, Germany (UG); National Mu- 022. FMNH: 21677; 25350; 49735; 52488;

seum of Natural History, Washington D.C. 68318. MACN: 14086; 17816; 25.33; 26186;

(USNM); Zoologisches Staatssammlung Mün- 26187; 29765; 30103; 34322; 34326; 34565;

chen, Munich, Germany (ZSM). 36230; 41163; 50446. MUSM: 01 J.O.; 415;

417; 418; 420; 421; 2150; 2151; 8467; 8468.

Catalog numbers.—Oreailurus jacobita.— MVZ: 114777; 114942; 114943; 139613. ZSM:

BM: 23.11.18.1; 23.11.18.2; 40.851. CBF: 1916/38; 1974/1.

00445; 02018; 02227; 02230. CGECM: 027. Felis catus.—AMNH: 14079; 41557; 133972;

MACN: 15.586; 29.200; 37.31; 37.32; 37.33; 248700. CBF: 4 uncataloged. CGECM: 028; 1

37.34; 37.36; 37.37; 37.38; 37.106; 37.107; uncataloged. MCZ: 51093. MVZ: 116007;

37.108; 37.109; 37.111; 37.112; 37.114; 37.116; 141633. USNM: 173336; 200285; 201072.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/83/1/110/2372706

by guest

on 15 April 2018

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Assignment #1Document2 pagesAssignment #1Rylee SimthNo ratings yet

- Oral Physiology and Occlusion ReviewerDocument100 pagesOral Physiology and Occlusion ReviewerNUELLAELYSSE DELCASTILLO100% (3)

- ENDO Lec FINALSDocument6 pagesENDO Lec FINALSDarryl Bermudez De Jesus100% (2)

- WHO OHS Form Adults 2013 PDFDocument2 pagesWHO OHS Form Adults 2013 PDFHana Fauziyah SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Fixed Functional Appliances For Treatment of Class II Malocclusions Effects and LimitationsDocument35 pagesFixed Functional Appliances For Treatment of Class II Malocclusions Effects and LimitationsAya ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Tooth EruptionDocument12 pagesTooth EruptionibrahimNo ratings yet

- Restorative Package $449 Ti - $499 ZR: Tooth #Document1 pageRestorative Package $449 Ti - $499 ZR: Tooth #Jean-Christophe PopeNo ratings yet

- Linguistics IPA and PronunciationDocument2 pagesLinguistics IPA and PronunciationRussell KatzNo ratings yet

- Ujian ObDocument2 pagesUjian ObElsha ZaskiaNo ratings yet

- Adhesion of Root Canal Selaers To DentinDocument6 pagesAdhesion of Root Canal Selaers To Dentinfun timesNo ratings yet

- Kim Tae Woo - Contemporary Multiloop Edgewise Archwire MEAW Technique - Old Fashioned But UsefulDocument20 pagesKim Tae Woo - Contemporary Multiloop Edgewise Archwire MEAW Technique - Old Fashioned But UsefulRodrigo my100% (1)

- Sefalo 3Document6 pagesSefalo 3Aisha DewiNo ratings yet

- Basic Life Support: 1St AssingnmentDocument2 pagesBasic Life Support: 1St AssingnmentHessa AloliwiNo ratings yet

- 2020 Dental-CertificateDocument1 page2020 Dental-Certificateคามาร์ คามาร์No ratings yet

- Prosthetic Management of Edentulous Mandibulectomy Patients - Part I. Anatomic, Physiologic, and Psychol PDFDocument12 pagesProsthetic Management of Edentulous Mandibulectomy Patients - Part I. Anatomic, Physiologic, and Psychol PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- The Speech Chain The Speech Mechanism and The Organs or SpeechDocument18 pagesThe Speech Chain The Speech Mechanism and The Organs or SpeechfrankyNo ratings yet

- Seminar - Supportive Periodontal TherapyDocument31 pagesSeminar - Supportive Periodontal Therapypalak sharmaNo ratings yet

- OralDocument3 pagesOralShaii Whomewhat GuyguyonNo ratings yet

- De Jongh - 2011 - A Test of Berggren S Model of Dental Fear and AnxietyDocument5 pagesDe Jongh - 2011 - A Test of Berggren S Model of Dental Fear and AnxietyENo ratings yet

- FluoriosisDocument73 pagesFluoriosisnathanielge19No ratings yet

- An Overview of Orthodontic Wires: Trends in Biomaterials and Artificial Organs March 2014Document6 pagesAn Overview of Orthodontic Wires: Trends in Biomaterials and Artificial Organs March 2014DrRohan DasNo ratings yet

- ITI Study Club-May EventDocument2 pagesITI Study Club-May EventS. BenzaquenNo ratings yet

- Tooth Implant Supported Prosthesis - A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesTooth Implant Supported Prosthesis - A Literature Reviewali almutrafiNo ratings yet

- Brachycephalic Dolichocephalic and Mesocephalic IsDocument6 pagesBrachycephalic Dolichocephalic and Mesocephalic IsDian PuspitaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Jaw MaxxingDocument14 pagesJaw MaxxingPavan JayaprakashNo ratings yet

- Oral Myofunctional and Articulation Disorders in Children With Malocclusions - A Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesOral Myofunctional and Articulation Disorders in Children With Malocclusions - A Systematic Reviewalba farran martiNo ratings yet

- 1st YearDocument8 pages1st YearPrakher SainiNo ratings yet

- Single Denture - II-Combination SyndromeDocument30 pagesSingle Denture - II-Combination SyndromeIsmail HamadaNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and Palate Seminar Ed PDFDocument100 pagesCleft Lip and Palate Seminar Ed PDFsaranyaazz100% (2)

- 13 Bergamo2022Document10 pages13 Bergamo2022jessicajacovetti1No ratings yet