Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ansell Collaborative Platforms

Ansell Collaborative Platforms

Uploaded by

Sitta NusapituCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ansell Collaborative Platforms

Ansell Collaborative Platforms

Uploaded by

Sitta NusapituCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Public Administration Research And Theory, 2018, 16–32

doi:10.1093/jopart/mux030

Article

Advance Access publication October 7, 2017

Article

Collaborative Platforms as a Governance

Strategy

Chris Ansell,* Alison Gash†

*University of California; †University of Oregon

Address correspondence to the author at cansell@berkeley.edu.

Abstract

Collaborative governance is increasingly viewed as a proactive policy instrument, one in which

the strategy of collaboration can be deployed on a larger scale and extended from one local con-

text to another. This article suggests that the concept of collaborative platforms provides useful

insights into this strategy of treating collaborative governance as a generic policy instrument.

Building on an organization-theoretic approach, collaborative platforms are defined as organiza-

tions or programs with dedicated competences and resources for facilitating the creation, adapta-

tion and success of multiple or ongoing collaborative projects or networks. Working between the

theoretical literature on platforms and empirical cases of collaborative platforms, the article finds

that strategic intermediation and design rules are important for encouraging the positive feedback

effects that help collaborative platforms adapt and succeed. Collaborative platforms often promote

the scaling-up of collaborative governance by creating modular collaborative units—a strategy of

collaborative franchising.

The term “platform” appears everywhere these days, widening and deepening their sphere of collaboration

popularized by spectacularly successful technology and producing spin-off collaborations? The second

platforms like the Apple iPhone and by closely related is how can collaborative governance be purposefully

concepts like open source innovation or crowdsourc- extended and scaled-up? Drawing on an expanding

ing. The term has now begun to creep into the lexi- literature on platforms, we suggest that the concept

con of governance. What we might once have called of collaborative platforms offers insights that address

a meeting, conference, partnership, clearinghouse or both of these questions.

network may now be branded a platform—as in the A decade and more of scholarship has explored the

case of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform trend toward collaborative modes of governance. As a

on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, the European general term, collaboration refers to a “high intensity”

Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion, or mode of interaction (Keast, Brown, and Mandell 2007,

the FramingNano Governance Platform. Is this mere 12) that nurtures mutual interdependence and joint

fashion or does the term signal a distinctive logic of action while preserving the autonomy of collaborating

governance? parties (Thomson, Perry, and Miller 2009). As a mode

This article explores the intersection between the of collective action for achieving public purposes, col-

platform concept and the better-known concept (at laborative governance refers broadly to “the processes

least in the fields of governance and public administra- and structures of public policy decision making and

tion) of collaborative governance. This exploration is management that engage people constructively across

useful for addressing two questions. The first is why do the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government,

some collaborations become more elaborate over time, and/or the public, private and civic spheres” (Emerson,

© The Author 2017. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Public Management Research Association. 16

All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 17

Nabatchi, and Balogh 2012, 2) or more narrowly to more legible, our goal is to explore the meaning and

the engagement of stakeholders in a “collective deci- applicability of the platform concept itself. The idea

sionmaking process that is formal, consensus-oriented is now widely used in the management, organization

and deliberative” (Ansell and Gash 2008, 2) where par- theory, and computer science literatures (Thomas,

ticipants “co-produce goals and strategies and share Autio, and Gann 2014). However, it has received lit-

responsibilities and resources” (Davies and White tle attention from governance or public administration

2012). In the past, governments, international organi- scholars. Drawing on the concept of web or software

zations, local communities, and foundations have often platforms, a few scholars have begun to focus on

turned to collaborative governance as a last resort when platforms as a strategy of e-government (Janssen and

other strategies have failed. More recently, they have Estevez 2013; Klievink, Bharosa, and Tan 2016; Koch,

begun to envision collaborative governance as a more Füller and Brunswicker 2011; O’Reilly 2011; Ranerup,

proactive policy instrument on a grander scale. For Henriksen, and Hedman 2016). Although very useful,

example, to meet the sustainable development goals of these contributions tend to associate platforms with

the UN’s Agenda 2030, World Vision International and information technology. By contrast, we view them

the Partnering Institute write: “If the bold (and wel- here as a generic organizational logic. Our interest is

come) vision of Agenda 2030 is to be realised, multi- in understanding how this generic organizational logic

stakeholder collaborations, and the platforms that might serve as a governance strategy via the promotion

can catalyse them, need to expand more rapidly than of collaborative governance.

at present” (2016, 4). To achieve “collective impact,” Despite the increasing use of the term platform to

it is argued, deeper and more extensive collaboration describe governance arrangements, few scholars have

must be fostered by strong and independent “backbone yet examined this more human-centered conception of

organizations” (Kania and Kramer 2011, 39). platforms as a strategy of governance. One important

Although we now know a good deal about multi- exception is Nambisan’s (2009) analysis of “collabora-

stakeholder collaborations, the governance literature tive platforms” as a strategy of societal problem-solv-

has scarcely recognized “the platforms that can cata- ing. He distinguishes three distinct types of platforms:

lyze them” or the “backbone organizations” that foster exploration platforms bring problem-solvers together

them. We propose to call such organizations collabora- to frame and investigate problems; experimenta-

tive platforms, which we understand in the broadest tion platforms bring people together to explore and

sense to be structured frameworks for promoting col- evaluate potential solutions; and execution platforms

laborative governance. Sometimes platforms develop encourage collaborative implementation of solutions.

inadvertently. Green (2013), for instance, describes Platforms have also been recognized as a governance

how the Clean Development Mechanism created by strategy in certain policy sectors, such as humani-

the Kyoto Protocol became a “coral reef” attract- tarian relief (Ogelsby and Burke 2012), agricultural

ing private rulemaking bodies to the climate change innovation (Nederlof et al., 2011), regional economic

regime complex. Our focus, however, is on structured development (Cooke 2007; Harmaakorpi 2006) and

frameworks designed to explicitly support and facili- sustainable development (Reid, Hayes, and Stibbe

tate collaborative governance. 2014).

As a strategy for scaling up or deepening collaborative Although this work has begun a conversation about

governance, platforms inherit and in some cases mag- platforms as a governance strategy, more needs to

nify the challenges of the basic approach. Collaborative be done to translate the logic of platforms from the

governance can be fragile, time consuming, and risky domain of technology, software development and even

and can lead to least common denominator outcomes; organization theory to that of governance and public

when it fails, it can accentuate skepticism and con- administration. Collaborative platforms fill a particu-

flict, and when it succeeds, it is often due to contextual lar niche in the world of governance: they specialize

factors such as inspired leadership or conditions that in facilitating, enabling, and to some degree regulat-

promote voice over exit. Yet collaborative platforms ing, “many-to-many” collaborative relationships. The

typically do not mandate collaboration or collaborative phrase “many-to-many” helps to reinforce the sense of

governance, but rather catalyze and facilitate voluntary the distinctiveness of collaborative platforms, which

efforts. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that can be contrasted with now-familiar commercial plat-

scaling up or extending collaborative governance will forms. In both a “multi-sided” market platform like

be a more appropriate and successful strategy where Uber and in collaborative platforms, the platform

contextual conditions already push or pull constituent plays a role of “meta-governance” or “orchestration.”

groups in this direction. But multi-sided market platforms bring together a

In addition to making how collaborative governance willing buyer and seller to facilitate a bilateral market

is being promoted as a proactive policy instrument exchange while collaborative platforms orchestrate a

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

18 Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1

multilateral (as opposed to bilateral) collaborative an international environmental NGO—the Nature

relationship (as opposed to market exchange). Conservancy—and the Indonesian government, the

CTC’s work focuses on creating Marine Protected

Areas (MPAs). Its ultimate goal is to create a “net-

Examples of Collaborative Platforms

worked system” of MPAs in the coral triangle (Coral

Since the idea of collaborative platforms is not widely Triangle Center 2016). Since its formation in 2010, the

appreciated, we begin by providing three concrete CTC has been actively involved in providing training

examples representing different policy sectors and on the concept of MPAs and in fostering “learning net-

regions of the world. These examples will be used to works” to share knowledge and best practices.

motivate our subsequent theoretical analysis. At the core of the MPA concept is a strategy of build-

ing local partnerships for protecting marine resources.

Together Let’s Prevent Childhood Obesity (EPODE) As a CTC staffer describes it: “CTC’s role is to bring

EPODE (Ensemble Prévenons l’Obésité Des Enfants actors together...[and it] strongly advocates a collab-

or Together Let’s Prevent Childhood Obesity) is a plat- orative approach’ (quoted by Berdej and Armitage

form that aims to prevent obesity in children. Started 2016, 10). For example, on the Indonesian island of

in France in 2004, it has since become the largest glo- Nusa Penida, the CTC has sought “to catalyze new

bal obesity prevention program (Borys et al. 2012; Van institutions and forums for interaction” and had spon-

Koperen et al. 2013). EPODE works by mobilizing sored over 60 forums with local stakeholders by 2014

stakeholders on a national and local basis to organ- (Berdej and Armitage 2016, 13). This effort includes

ize local obesity campaigns. On the national level, the helping groups like ecotourism operators organize so

program first brings high-level stakeholders together that they can participate more productively in mar-

to generate political commitment for a national pro- ine protection activities. Consequently, Berdej and

gram. It then recruits and trains local project managers Armitage (2016) find that the CTC is at the center

to organize local steering committees that will develop of the island’s collaboration, knowledge-sharing, and

local obesity prevention campaigns. funding networks related to marine protection.

In mobilizing for local obesity campaigns, EPODE

program managers identify those already actively East Africa Dairy Development Program

involved in the issue and build on existing efforts. East Africa Dairy Development (EADD) has been

Borys et al. describe their role: described as an “agricultural innovation platform”

The local project manager takes responsibility that aims to promote smallholder dairy production

for managing the multidisciplinary local steer- in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (Kilelu et al. 2013).

ing committee of professionals in order to foster The program is a consortium composed of Heifer

positive peer-to-peer dynamics and accelerate the International, the International Livestock Research

implementation of local actions by a wide variety Institute (ILRI), Technoserve, the African Breeders

of local stakeholders (Borys et al. 2012, 303). Services Total Cattle Management Limited, and the

World Agroforestry Centre, with major funding from

Obesity campaigns are tailored to local conditions, but the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The consor-

they draw on a methodology that EPODE has devel- tium organizes dairy farmers and other key stakehold-

oped over time. This methodology stresses the use of ers to expand the dairy market in East Africa with the

social marketing techniques to raise awareness and ultimate goal of enhancing farmer livelihoods.

change cultural attitudes about obesity. Advancing the At the heart of the EADD strategy is what the con-

EPODE brand is also a strong element of its organiz- sortium calls the “hub model,” which has four basic

ing philosophy and is used to help diverse local stake- components: (1) organizing farmers and strengthening

holders feel part of a positive shared project. By 2011, their associations; (2) facilitating access to improved

more than 500 communities in six countries (France, production technologies; (3) improving access to mar-

Belgium, Spain, Greece, Australia, and Mexico) had kets; and (4) stimulating business development services

organized EPODE campaigns (Borys et al. 2012). (Bisagaya 2014). Hubs are groups of local dairy farm-

ers who join together to create business associations

The Coral Triangle Center and limited liability companies that provide shared

The coral triangle is an area of exceptional marine support services. At the heart of this cooperation is typ-

diversity situated between Indonesia, Malaysia, the ically the establishment of a milk chilling facility that

Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste and the allows smallholders to store their product so that they

Solomon Islands. The Coral Triangle Center (CTC) can achieve greater market access and higher returns.

was established in 2010 to help protect this rich but Since 2008, the program has created 27 hubs and

fragile resource. Created through the cooperation of strengthened 10 existing hubs (Heifer International

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 19

2016). These hubs were initially organized by mobiliz- discussion of the architecture of software code (Evans,

ing relevant political stakeholders and then conducting Hagiu, and Schmalensee 2008). A more useful place

public meetings where local communities were invited to begin is with the literatures on “platform organi-

to establish interim boards of directors. EADD then zations” and “innovation platforms.” Ciborra (1996)

works with these boards to establish governance struc- was the first to analyze organizations as platforms,

tures and business plans for these local hubs. Once the using the concept to describe the innovation strategy

local dairy companies are established, EADD works of the Italian firm Olivetti. He described a platform

with them to link them to a range of support services as a “…a formative context that molds structures, and

(e.g., veterinary, marketing, etc.) that farmers can routines shaping them into well-known forms, such as

access using a credit-based system. the hierarchy, the matrix and even the network, but

Although our focus is on the organizational logic on a highly volatile basis” (Ciborra 1996, 103). From

of these collaborative platforms, we acknowledge at this definition, we can draw out several characteristics

the outset that platforms are not apolitical technolo- of platforms. First, platforms provide a framework

gies. An evaluation of a collaborative platform called upon which and through which other activities may be

Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) offers a vivid example of organized; second, this framework is relatively stable

its political character: through time, but the activities that take place upon

it may be easily and flexibly organized and reorgan-

SUN’s engagement with corporate business is

ized. In Ciborra’s terms, they are easily “reconfigur-

anathema for some, while others see SUN as

able” (Ciborra 1996, 115). Third, the platform is not

not taking a sufficiently rights-based approach,

merely a passive support structure; it facilitates this

ignoring the underlying food system causes of

reconfigurability.

hunger and malnutrition, and also undermining

The literatures on product and innovation plat-

the UN governmental forums, including the CFS

forms make similar types of arguments, noting that

and WHA, that they regard as the proper source

platforms foster both stability and flexibility. These

of guidance on nutrition policy (Mokoro 2015,

literatures also describe the way platforms allow for

585–6).

a large variety of product extensions based on either

Like all other governance institutions, collabora- creating products that complement or plug in to a core

tive platforms are established with agendas that have product or based on the recombination of component

admirers and detractors. parts. Nearly all uses of the platform concept empha-

In the remainder of the article, we take on three size that platforms create either a space or an interface

tasks. The first is to clarify the basic concept of a plat- to facilitate the interaction of different skills, resources,

form, illuminating how it is distinctive and what it knowledge or needs. A platform may do this by facili-

may contribute to our understanding of collaborative tating the matching of interests, by creating standard-

governance. The second task is to deepen our under- ized technological interfaces or communication forums

standing of the organizational logics underlying col- or by creating cross-functional teams.

laborative platforms. The third task is to conceptually Modularity—an architecture that allows the easy

locate collaborative platforms in a wider family of gov- recombination of component parts—facilitates recon-

ernance platforms. figurability by creating opportunities for mass cus-

tomization or for massively customized products. In

a platform context, modularity is understood to allow

The Platform Concept interorganizational coordination while lessening the

To be sure, the platform concept poses challenges. Used need for overt managerial control (Furlan, Cabigiosu,

without critical reflection, it can become an evocative and Camuffo 2014). Such coordination is facilitated

umbrella concept that attracts attention while being by “design rules” that often standardize interfaces and

devoid of meaning. The term may simply trade on the communication protocols (Baldwin and Clark 2000).

reflected glory of powerful platforms like Apple with- Modularity and reconfigurability, in turn, create the

out providing real analytical insight. To make the term potential for an “ecosystem” of complementary prod-

concrete and to demonstrate its potential, we need to ucts, processes, and people (Gawer and Cusumano

be clear about what it entails and how it can be dis- 2014). Many studies suggest that platform ecosys-

tinguished from related ideas. Building on a growing tems are generated by positive feedbacks or “network

body of theoretical work on platforms, our goal is to effects.” These positive feedbacks are often created

adapt this work to the governance context. when the platform facilitates “open innovation” that

Although it is now common to talk about software allows third parties to utilize the platform for their

platforms such as JAVA, LINUX, or Mac OS, begin- own purposes. To generate a critical mass of inter-

ning our discussion here would quickly lead us into a est, successful platforms must be robust in the face of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

20 Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1

different agendas and combinations of skills, know- Collaborative platforms are often collaborative or

ledge, or interests. networked in form, but not necessarily so. This dis-

Collaborative platforms may be used to replicate tinction between collaborative platforms and collab-

collaborative governance on a wider scale, but they orative governance is important because these terms

may also be used to expand the scope of a single col- can otherwise become loosely interchangeable. For

laboration over time. We observe that in some cases example, a literature in natural resource management

collaborations become more elaborated over time, defines a “multi-stakeholder platform” as:

spawning multiple projects and spinoff collaborations,

producing a collaborative ecosystem as a result. Innes A negotiating and/or decision-making body

and Booher’s (2010) case study of the Sacramento Area (voluntary or statutory), comprising different

Water Forum provides a good example. To confront stakeholders who perceive the same resource

the region’s politically conflictual water management management problem, realize their interdepend-

issues, the Forum had to sustain itself through time, ence in solving it, and come together to agree on

adapting itself to a complex array of interlocking chal- action strategies for solving the problem (Steins

and Edwards 1999, 244).

lenges. Success entailed the creation of many teams,

entities, and agreements along the way. The success of This use of the term platform reflects the sense that it is

the Forum also had spin-off effects that came to “per- a foundation that intermediates between stakeholders

vade the governance culture in other policy arenas” and upon which collaboration can be built. However,

(Innes and Booher 2010, 50). The platform concept the definition is not easily distinguishable from what

helps us to see that the Forum is not a single collabor- the literature now calls collaborative governance. The

ation, but rather a foundation for the elaboration of a value-added of a concept like collaborative platform

wider collaborative ecosystem. comes from seeing the platform as the nexus of mul-

Drawing on this brief discussion, we can now pro- tiple collaborations or networks.

vide a basic definition of a collaborative platform: The platform concept complements, but also

A collaborative platform is an organization or extends, the idea of collaborative governance regimes

program with dedicated competences, institu- (CGRs) developed by Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh

tions and resources for facilitating the creation, (2012) and Emerson and Nabatchi (2015). They define

adaptation and success of multiple or ongoing CGRs as a “type of public governance system in which

collaborative projects or networks.1 cross-boundary collaboration represents the predom-

inant mode for conduct, decision making, and activ-

Each of the examples described in the introduction fits ity between autonomous participants who have come

this definition of a collaborative platform. EPODE cre- together to achieve some collective purpose defined

ates collaborative local campaigns for the prevention by one or more target goals” (Emerson and Nabatchi

of childhood obesity built on a basic social marketing 2015, 18). The concept of a regime, they argue, helps to

technology. The CTC catalyzes local stakeholder part- distinguish different types of collaborative governance

nerships around the basic institutional framework of and their typology of CGRs emphasizes how regimes

MPAs. The East African Dairy Development platform are formed—specifically, whether they are self-initi-

creates local hubs that link small farmers together in ated, independently convened or externally-directed

business associations around the shared technology (Emerson and Nabatchi 2015, 163). A platform may be

of a milk chilling facility. In each case, promoting col- considered a key component of an independently-con-

laboration is a basic policy instrument used to achieve vened or externally-directed regime. However, whereas

general ends. And in each case, distributed collabor- the regime typology takes the perspective of the result-

ation is facilitated by allowing stakeholders to plug ing collaboration, the platform concept focuses on the

into modular institutional frameworks or interfaces organization convening or directing the collaboration.

configured to local needs and contexts. Table 1 pro- Emerson and Nabatchi rightly express caution

vides a diverse range of examples that fit our basic def- about “externally-directed” collaborations, noting that

inition of a collaborative platform. mandated or preset forms of collaboration can fail to

produce on-the-ground collaboration (Emerson and

1 A collaborative platform is often a stand-alone organization, but may Nabatchi 2015, 174–5). This concern certainly carries

also be a program or a subunit of an organization. A “project” is a over to collaborative platforms. The concept of collab-

temporary organization formed to carry out a delimited agenda (Lundin orative platform, however, helps to call attention to the

and Söderholm 1995). A “network” is a “stable articulation of mutually way that “preset” conditions do or do not encourage

dependent, but operationally autonomous actors” (Sørensen and

Torfing 2009, 236). A collaborative project is typically a network, but a

on-the-ground collaboration. It also calls attention to

network (which implies collaboration) is not necessarily designed to be the platform’s facilitative as opposed to merely direct-

temporary or to carry out a delimited agenda. ive role in encouraging collaboration. Finally, while

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 21

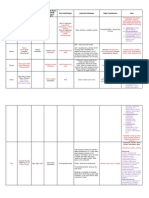

Table 1. Additional Examples of Collaborative Platforms

Platform Description

Innovation and economic development

Development Trusts Association Scotland (www.dtascot. DTAS facilitates the creation of locally-owned and managed

org.uk) development trusts by providing information, resources,

training and assistance to interested communities.

New Vision for Agriculture (www.wereform.org) A project of the World Economic Forum, NVA promotes

food security, environmental sustainability and economic

opportunity by catalyzing, brokering and facilitating

investment in regional and country-level agricultural

partnerships.

German National Platform for Electromobility (http:// GNPEM encourages regional and multi-sectoral collaborations

nationale-plattform-elektromobilitaet.de/en/) to encourage innovations that will allow Germany to become

the leading global supplier of electrical mobility by 2020.

Sustainability

Global Environmental Facility (www.thegef.org) A partnership of 18 international organizations, the GEF

catalyzes and supports multi-stakeholder alliances and

collaborative projects to preserve threatened ecosystems.

Water framework directive (www.ec.europa.eu) The WFD is an EU policy framework for integrated river basin

management that requires the development of local river basin

districts and collaborative basin planning.

Roundtable on the crown of the continents (http:// The Roundtable encourages collaboration at multiple scales to

crownroundtable.org) sustainably manage the Crown of the Continents—a region of

the Rocky Mountains straddling both the U.S. and Canada.

Health

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health A multi-sector coalition of more than 700 organizations in

(who.int/pmnch/en/) over 75 countries that promotes multi-stakeholder action to

improve the health of mothers, newborns and children and

adolescents.

LiveWell Colorado (livewellcolorado.org) A “bi-directional platform” that promotes local multi-sector

community coalitions to address obesity.

Forum for Action on A multisector platform sponsored by the Pan American Health

Non-Communicable Disease (www. Organization that catalyzes collaborative action at the

paho.org/panamericanforum) regional, subregional, and country level to address non-

communicable diseases.

Poverty and disaster relief

Vibrant Communities Canada (www.vibrantcanada.ca) A network of Canadian cities that promotes local multi-sector

collaborations to address urban poverty.

FT Kilimanjaro (www.ftkilimanjaro.org) Tanzanian NGO that has created nearly 40 collaborative

partnerships to develop an integrated approach to poverty

reduction in the Lower Moshi region of Tanzania.

Global Platform for Disaster Biennial forum for information sharing and multi-sector coalition

Risk Reduction (www.unisdr. building to improve communication and coordination in

org/we/coordinate/global-platform) disaster reduction.

the regime idea envisions the compound and sustained (Provan and Kenis 2008), or what the Collective

nature of collaborative governance, the platform con- Impact literature calls “backbone organizations”

cept directs our attention to the specialized task of (Kania and Kramer 2011). The network governance

facilitating and adaptively managing a bundle of col- literature has also been attuned to the importance of

laborative projects or networks. managing networks (Koppenjan and Klijn 2004) and

The platform concept can also be related to ideas has developed the concept of network metagovernance

developed in the literature on network governance. to describe how the state can engage in the “govern-

Provan and Milward (1995) found that networks with ance of governance” (Sørensen and Torfing 2009). This

central coordinating bodies offered better integration work calls attention to idea that the role of facilitat-

of mental health services. Subsequent research found ing or managing networks is often a specialized one

that many networks are managed by “lead organi- that provides strategic direction for the formation and

zations” or “network administrative organizations” management of networks. A platform is much like a

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

22 Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1

lead or network administrative organization that gen- deeper exploration of the basic logics of collaborative

erates and metagoverns a portfolio of collaborative platforms.

projects and networks.

Although our definition of collaborative platforms

A Deeper Dive: The Logics of Collaborative

stresses its organizational dimensions and distin-

Platforms

guishes the platform itself from the collaborations it

fosters, we note that it may often be difficult to dis- In this section, we work back and forth between

tinguish them in practice. Platforms facilitate multiple, the theoretical literature on platforms and concrete

on-going collaborations. In doing so, the collabora- examples that meet our definition of a collaborative

tions may simply appear to be extensions of the plat- platform. Our goal is to isolate distinctive logics of col-

form. For example, local obesity campaigns organized laborative platforms, by which we mean their charac-

under the aegis of EPODE are branded as EPODE teristic modes of operation.

campaigns. Even where there is a sharper demarca- A first point is that collaborative platforms tend

tion between the platform organization and its affili- to have high-level or open-ended goals or strategies

ated collaborations, elements of the platform may be that are given meaning and substance through specific

embedded in a distributed fashion into the collabora- collaborations (Selsky and Parker 2005, 2010). For

example, Oxford House Inc., is a collaborative plat-

tions it helps to organize. For example, the CTC is an

form that helps recovering alcoholics create coopera-

active participant in the many local collaborations it

tive housing arrangements. The overarching goal of

facilitates. Thus, although we have noted the similari-

Oxford House is to help sustain sober living. However,

ties here between platforms and network administra-

each individual Oxford House has the freedom to

tive or backbone organizations, the boundary between

develop its own specific approach as long as the prin-

platforms and the collaborations they promote may

ciples and values of the Oxford House framework are

often be fuzzy.

followed (Jason et al. 2001).

An important value of the platform concept is that

One implication of maintaining broad goals that

it offers a useful framework for distinguishing one-off

are then given substance by configuring specific

or short-term instances of collaborative governance

modular frameworks is that platforms are described

from more adaptive or sustained efforts. Platforms

as being “evolvable” (Baldwin and Woodard 2009).

generate collaborations or networks and help modify The relationship between open-ended goals and the

them as conditions change. There is thus a temporal evolvability of a platform can be seen in the case of

dimension to the platform concept. Inherent in the the adaptation over time of community health part-

concept of platform as developed by Ciborra is the nerships. Cheadle et al. (2005) distinguish between

idea that platforms create a stable framework to facili- issue-specific health partnerships and partnerships

tate a more flexible mode of governance that adapts with broader and less focused goals (e.g., improv-

over time to new opportunities or changing condi- ing community health). They find that partnerships

tions. Thus, collaborative platforms may serve as a with broader and less focused goals tend to expand

strategy of adaptive governance, helping to generate over time, incorporating multiple stakeholders and

or reorganize projects and networks as new opportu- elaborating new projects, whereas partnerships who

nities or challenges arise. Here again, the usefulness set out to address specific issues tend to narrow and

of the term depends on being able to distinguish a professionalize.

relatively enduring set of organizational competences, Evolvability is an important property because

institutions and resources for generating and adapting platforms often have to discover their value-added

collaboration from the specific projects or networks in role adaptively. For example, a Ugandan agricultural

question. Drawing this distinction is probably easier innovation platform had “…to go through a trajectory

where the platform and its collaborative projects or of discussion and turbulence before it discover[ed] its

networks operate at different scales (e.g., EPODE, proper function” by “finding complementarities and

EADD) and somewhat more difficult where a single synergies with on-going value chain interventions”

collaborative (e.g., Sacramento Water Forum) grad- (Nederlof et al. 2011, 121). This relationship between

ually becomes more differentiated. open-ended goals and evolvability poses a challenge

In defining collaborative platforms, this section has for platform design, as O’Reilly observes: “How do

argued that the concept is useful when we wish to you design a system in which all of the outcomes aren’t

describe a distinctive institutional framework for pro- specified beforehand, but instead evolve through inter-

moting multiple collaborations or for facilitating the actions between government and its citizens, as a ser-

adaptation of many collaborative projects over time. vice provider enabling its user community?” (Nederlof

Having defined the basic concept, we now go on a et al. 2011, 15). Although platform goals may be broad

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 23

and open-ended, we should not mistake this for ad hoc intermediaries.” One of the strategic intermediaries they

informality. Platforms strive to provide a stable and describe, the Merseyside Basin Campaign (MBC), fits

structured framework in which more dynamic and well with our definition of collaborative platforms; this

adaptable processes can evolve. regional water coalition advances its agenda by promot-

Platforms tend to operate in a context of distrib- ing local “river initiatives.” The innovation literature also

uted action, which means they serve as an umbrella calls attention to the importance of “systemic interme-

for many diverse and semi-independent activities and diaries” operating at a strategic level between networks

actors. Baldwin and Woodard (2009) describe this in and systems (Van Lente et al. 2003). These systemic

evolutionary terms, arguing that platforms promote intermediaries act as a catalyst for system innovation by

variation. However, platforms also promote integra- intermediating between subsystems, in part by creating

tion by creating interfaces that integrate diverse and “platforms for experimentation and learning” (Klerkx

semi-independent activities into an interacting system. and Leeuwis 2009, 855). As these descriptions of inter-

In doing this, they serve as “boundary objects” (Star mediation suggest, intermediaries operate as a nexus of

and Griesemer 1989) or “boundary organizations” networks or collaborative efforts.2

(Guston 2001). Platforms often provide multi-level intermediation

Integrating distributed action may sound entirely between local collaborative projects and national or

unexceptional. All organizations do this. Platforms, international resources and political authority. This

however, push the limits on the distributed action side of vertical intermediation can be challenging. Desportes

the equation. As noted earlier, collaborative platforms et al. (2016) describe the political and institutional

facilitate, enable and regulate many-to-many ties. They limits encountered by a collaborative platform created

do this by promoting parallel and semi-autonomous in Cape Town, South Africa to deal with the issue of

organizing, on the one hand, and aggregating or coor- flooding. The platform successfully mobilized collab-

dinating these organizing efforts on the other. Oxford oration among local residents, but “could not get the

House, Inc., for example, offers individuals interested flooding issue on the agenda of officials and politi-

in forming an Oxford House with resources and guid- cians beyond the Task Team” (Desportes et al. 2016,

ance for setting up their home and navigating local 79). Some platforms explicitly address this challenge.

zoning procedures or funding obstacles but provides EPODE first organizes high-level political support in

ample space for each home to develop its own initia- a country before committing to building a local obes-

tives and operate according to its own rules. ity campaign. Agriculture innovation platforms often

One of the ways that platforms achieve a working operate on a national level to build political support

balance between distributed action and integration is and on a local level to engage with farmers and other

through extensive use of intermediation. Kilelu et al. stakeholders (Nederlof et al. 2011).

describe the intermediary role played by EADD: Intermediation is a more prominent logic of action

for platforms than control (e.g., via authority or regu-

“…[A]n important intermediation role of EADD lation), though control is not absent. Since platforms

at the early stages was to mobilize farmers, sup- typically build on the voluntary contributions of inde-

port the interim leadership of the DFBAs to pendent or semi-independent stakeholders, they rarely

draw up business plans, facilitate the set-up of exercise a sufficient degree of power over stakehold-

governance structures, and bring on board other ers to directly control their interactions. Yet they must

relevant actors as collaborators, broker their ensure some degree of integration or at least effect-

interactions and support the interim leadership ive adjudication. To some degree, platform control

to raise capital” (Kilelu et al. 2013, 70). is ecological; it is achieved indirectly by designing

The important role of intermediaries has been increas- the institutional framework in which many-to-many

ingly noted in the literature on economic development interaction is orchestrated. The literature on modu-

and environmental protection (Geels and Deuten 2006; larity emphasizes that control is achieved via “design

Hargreaves et al. 2013; Medd and Marvin 2007; Moss rules” (Baldwin and Clark 2000; Tiwana, Konsynski,

2009). Geels and Deuten (2006) describe how indus- and Bush 2010), particularly the design of “interfaces”

trial intermediaries may evolve over time from serving a (Hagiu and Wright 2015).

knowledge “aggregating” role to a more “orchestrating” Getting the balance right between intermediation

role. Hargreaves et al. (2013) build on this model, but and control is important for what has been referred to

argue that the energy-related intermediaries go beyond as the “generativity” of platforms (O’Reilly 2011). A

this orchestration role to take a direct role in creating

networks and thus acting very much like the platforms 2 As Consoli and Patrucco describe for innovation platforms, a platform

described here. Collaborative platforms often assume becomes “the coordination of a bundle of inter-firms and inter-

the role of what Medd and Marvin (2007) call “strategic organizations linkages” (Consoli and Patrucco 2008, 703).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

24 Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1

generative technology creates easily masterable “levers” First, responding to voluntarism, platforms must build

that make jobs easier, are easily adapted to new pur- on existing motivations for action; they must then

poses, and easily accessible to wide audiences (Zittrain spot where intermediation is likely to create value that

2006). Recall the core institutional interfaces of the can feedback to deepen subsequent commitment and

three platform examples presented in the introduc- investment. By this logic, platforms are likely to do

tion. EPODE’s social marketing techniques, the CTC’s well where opportunities for value creation via inter-

concept of MPAs, and the EADD’s use of hubs are all mediation are rich. We identify four types of positive

potentially generative in the sense that they facilitate feedbacks that collaborative platforms might strategic-

the task of collaboration, are configurable to local con- ally target to build success.

texts, and are made accessible to wide audiences.

A key design issue related to intermediation, control Attractor Effects

and generativity is the relative openness of the platform. The literature on commercial platforms talks about

Platforms are often associated with open innovation, their positive network effects—the idea that the more

which allows users to freely access and utilize the basic developers and users affiliate with the platform, the

resources and infrastructure of the platform for their own more that others will want to affiliate. Success begets

purposes. Boudreau (2010) distinguishes at least two dif- success. We refer to this type of positive feedback as

ferent modes of opening a platform. One is to grant open an “attractor effect.” In the context of collaborative

access to the platform, which remains under the control governance, stakeholders may become more willing

of the platform owners; the other is to devolve a degree to invest time, energy and resources in collaborations

of control over the platform. He finds that the later strat- that appear to be producing tangible and successful

egy produces positive innovation effects. EPODE cam- outcomes. For example, Weber describes the long-

paigns, EADD diary hubs, and Coral Triangle MPAs term evolution of the Blackfoot Challenge, a successful

seem to reflect this later strategy of devolving a large watershed collaboration in Montana. Over time, this

measure of control over the platform. As Jansen and group has helped to organize over 100 projects. Weber

Estevez note, “The whole idea of platform is to create a describes this collaboration as building on an attractor

community, and by doing so lowering transaction costs, effect “…the overall character of the Blackfoot

increase reach and enable some level of control by users” Challenge was a magnet that drew stakeholders to the

(Janssen and Estevez 2013, S5). Herein lies a challenge. group” (Weber 2012, 41).

Referring to e-government platforms, Jansen and Estevez Ideally, platforms promote value-creating collabo-

note that: “[t]oo tight control might scare developers, rations, which then feedback to motivate wider par-

too loose might result in anarchy” (Janssen and Estevez ticipation. In their study of agricultural innovation

2013, S6). With respect to collaborative platforms, platforms, Nederlof et al. note that the “[t]he challenge

greater control over access and participation can reduce is to find a match between quick wins, showing the

transaction costs and facilitate negotiation and coordin- relevance of a platform and joint action” (Nederlof

ation; it can also undermine legitimacy, discourage fresh et al. 2011, 122). We noted earlier that in the context

ideas, and limit possibilities for synergy. of community health partnerships, broad-based goals

The advantages of opening up platforms can be seen tended to attract more collaborators over time, whereas

in an example from crowdsourcing platforms. Roth et narrower goals did not. However, overly broad goals

al. (2013) describe two regional crowdsourcing plat- may discourage concrete value creation and hence

forms with varying degrees of openness. One of them fail to attract participation. Genskow (2009) investi-

allows only those from within the region to submit ideas, gated Wisconsin’s efforts to “catalyze” watershed-level

whereas the other is open to submissions from beyond collaboration on a statewide basis. Some watershed

the region. Roth et al. argue that the greater openness organizations developed well and became institution-

of the later region makes it more likely to break out alized; others never developed a clear focus or became

of “regional lock-in.” A number of platform discus- firmly established. He concluded that: “Agencies ini-

sions suggest that platforms can become more closed tiating collaborative resource management efforts are

as incumbent stakeholders take control. Stakeholders more likely to succeed by providing a specific purpose

may only be incentivized to make investments in plat- and focusing on specific issues and areas” (Genskow

form activities when they feel like they have a sense of 2009, 422).

control over the fate of their investment. As a result,

greater openness may undermine their desire to invest Learning

in the platform. Generativity may hang on the precise A number of scholars have explored the links between

balance struck between an open and a closed platform. collaborative governance and learning (Gerlak and

The ideas developed in this section point to how Heikkila 2011; Leach et al. 2013; Pahl-Wostl 2007).

collaborative platforms must act in a strategic manner. Here we focus on learning something in the course of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 25

collaboration—typically about collaboration itself— the importance of “‘starting where the people are’—

that then positively feedbacks to reinforce the vitality that is identifying issues that are of immediate con-

of the platform. For example, stakeholders working cern to community residents” (Cheadle et al. 2005,

together may learn over time how to collaborate suc- 649). In the context of agricultural innovation plat-

cessfully; these lessons can then become the basis for forms, Nederloff et al. point to the value of identifying

extending collaboration to new issues. “…‘farmer “champions’ who are highly motivated and

We can identify several scenarios for how learning therefore used to help mobilise farmers in their com-

may serve as a positive feedback. First, stakeholders munity, and to co-ordinate activities including input

working collaboratively might learn something about distribution and reporting on progress” (Nederlof

the nature of the issue that leads them to expand or et al. 2011, 126).

adapt their collaborative effort. A good example of this A closely related strategy of generating leverage on

type of learning can be seen in the institutional adap- collaborative platforms is customizing different activi-

tation of an estuary partnership described by Emerson ties for different stakeholders. Ton and Vellema argue

and Gerlak (2014)—the Piscataqua Region Estuaries that “Platform facilitators need to maximize the pos-

Partnership (PREP). Over time, PREP expanded its sibilities for spin-off activities with sub-sets of mem-

geographical scope, bringing in new stakeholders as it bers in the early stages of platform development, even

did so. The trigger for this expansion was a recogni- when these may not be the most important activities

tion of the limits of addressing estuary problems from in the long term for the group as a whole” (Ton and

a narrow geographic base. Vellema 2010, 1). In their study of EPODE, Borys et al.

Second, collaborative knowledge acquisition can observe the strategic importance of the “ability to gen-

deepen the commitment of stakeholders to participate erate social multiplier effects (e.g., through the involve-

and has been found to be related to belief change (Leach ment of stakeholders in ‘different forms of dialogue

et al. 2013). Third, positive learning feedback can and partnerships’ and ‘effective channels of communi-

occur when stakeholders learn how to work together cation’) and a combination of multiple interventions”

in fruitful ways and build upon this knowledge in their (Borys et al. 2012, 312).

subsequent interaction. Crona and Parker’s (2012)

example of an environmental bridging organization, Synergy

the Decision Center for a Desert City (DCDC), illus- Platforms can produce positive feedback effects by

trates both of these processes. This organization’s cre- bringing stakeholders together with synergistic know-

ation of a “politically neutral” space for joint learning ledge, skills, resources, and perspectives.3 Nederlof

reduced the cultural barriers to increased networking et al., describe successful momentum on a Ugandan

among stakeholders. Collaborative knowledge acqui- agricultural innovation platform:

sition through the development of a regional water

model fed back to improve the model, which in turn “Although literature may suggest otherwise,

reinforced collaboration. namely that diversity within a group impairs

joint action and strategising, the diversity within

this platform turned out to be a valuable asset.

Leverage

To be able to represent the diverse perspectives in

Thomas et al. (2014) argue that platforms are suc- a fair way depended on good (external) facilita-

cessful when they exercise “architectural leverage.” tion as well as on finding complementarities and

By leverage, they mean that the platform creates synergies with on-going value chain interven-

multiplier effects: “leverage refers to a process of gen- tions, such as contract farming or group-based

erating an impact that is disproportionately larger bulking” (Nederlof et al. 2011, 121).

than the input” or “exercising an influence dispro-

portionate to one’s size” (Thomas et al. 2014, 206). The EADD adopted a strategy of building synergies

They argue that “leverage is achieved through devel- around local hubs by enabling “…the formation of dif-

oping shared assets, designs, and standards that can ferent lateral networks to address a variety of emerg-

be recombined, thereby facilitating coordination and ing issues relevant to the overall innovation process…”

governance…” (Thomas et al. 2014, 206). As this (Kilelu, Klerkx, and Leeuwis 2013, 75).

statement suggests, modularity can facilitate platform We summarize the key points made in this section

leverage. EADD’s promotion of diary hubs offers a about collaborative platforms in table 2.

good example of how collaborative platforms might

achieve architectural leverage.

3 Pitsis, Kornberger and Clegg argue that in the context of

One key strategy for achieving leverage is to build interorganizational collaboration, synthesis means “something new

on pre-existing efforts and motivations. In their study and different is created from the combination of the two parts” (Pitsis,

of community health partnerships, Cheadle et al. note Kornberger, and Clegg 2004, 47).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

26 Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1

Table 2. The Concept of Collaborative Platforms

Agenda Scale and scope: Extend scale and scope of collaborative governance

Adaptive governance: Adapt to changing conditions and contexts by creating and reconfiguring

collaborative efforts as needed

Institutional nexus: Catalyze and orchestrate multiple or ongoing collaborative governance projects

Distinctive logics Strategic Intermediation: Prioritizes intermediation (over control) as a way of mobilizing and integrating

distributed action

Design rules: collaboration facilitated and managed through design of modules or platform interfaces,

access rules and participation eligibility and requirements

Structure Modularity: Manages the tension between centralized intermediation and decentralized action through

modular structures

High variation and integration: Extends the capacity to mobilize distributed action while providing a

framework for integrated action

Strategy Generative: Manage the balance between open and closed participation in order to encourage both

commitment and diversity

Positive feedback: Invest in and expand existing energies with an eye toward producing positive value-

creating feedbacks (via attraction, learning, leverage and/or synergy)

Collaborative Platforms In Wider Platforms have responsibilities for managing both

Perspective vertical and horizontal interdependence. When hori-

The platform concept has the potential to describe a zontal interdependence is pooled, the role of the inter-

family of governance strategies—a potential some- mediary is to aggregate or pool the separate inputs

times obscured by a narrow association of the concept of different constituents (Geels and Deuten 2006).

with software or internet platforms. Building on the A crowdsourcing platform, for example, typically uses

ideas about intermediation and design rules developed a web portal to aggregate the ideas from a wide variety

in the previous discussion, this final section surveys a of individuals or groups. The platform plays little role

range of platform types, not all which are collaborative in trying to orchestrate such activity. However, as the

platforms as we have defined them. Thus, this section interdependence of constituent groups becomes more

suggests the wider applicability of the platform con- reciprocal, intermediaries must engage in more “rela-

cept for governance and public administration, while tional work” to help coordinate them (Moss 2009).

locating how collaborative platforms fit within this The intermediary must often play a more catalytic

family of platforms. role to enact interdependence. Hanleybrown, Kania,

A common feature of all platform organizations is and Kramer’s (2012), for instance, find that “back-

that their purpose is to create a basis upon which a bone organizations” must facilitate dialogue between

distributed set of activities can develop. However, the partners.

intermediary role of platforms and their role in estab- Vertically, the focus is on the kind of relationship

lishing and managing the “design rules” of platform that must exist between the platform and its constit-

participation may vary considerably. This variation uents in order to properly align inputs and outputs.

reflects underlying conditions of interdependence. When the interdependence between the platform and

Platforms exhibit two types of interdependence. participating groups is pooled, each may have their

Vertical interdependence refers to the interdependence respective roles and they may interact in a limited fash-

between the platform and its constituents (members, ion to achieve those roles. However, as interdepend-

allies, suppliers, participants, etc.). Horizontal inter- ence becomes more reciprocal, tighter coordination

dependence refers to the interdependence between the between the platform and its participants becomes

constituents themselves. Both dimensions run from a important. Much of the literature that focuses on the

more limited form of interdependence that Thompson relationship between a core technological platform

(1967) called “pooled” to a more intense form he (e.g., an automobile chassis) and its modular compo-

referred to as “reciprocal.”4 nents is concerned with this vertical relationship. In

such cases, the platform owners tend to set out very

precise “design rules” specifying the design of modules

4 Interdependence is both a condition and a choice. People or groups and the interface for plugging in to the platform.

face a condition of interdependence when they find themselves Figure 1 focuses on the two institutional axes of

dependent upon others to achieve their goals. They can also decide to this discussion—design rules and intermediation. Our

enter into a relationship of deeper interdependence with others. This

discussion begins in the lower right cell of figure 1,

distinction is useful for keeping in mind that interdependence is both an

exogenous and an exogeneous factor and also that interdependence is where design rules are minimal and intermediation

both a functional and a political situation. is primarily aggregative. Crowdsourcing platforms

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 27

Figure 1. Logics of Platform Governance.

generally require pooled intermediation and limited platforms can be used to facilitate cross-organizational

control over distributed inputs (though the web por- collaboration.

tal interface is standardized). The UN’s refugee agency, Like crowdsourcing and knowledge platforms,

UNHCR, for example, created a crowdsourcing plat- benchmarking platforms aggregate performance infor-

form called “UNHCR Ideas” to encourage “open mation from a set of distributed participants (e.g.,

innovation” around its practices (Bloom 2014). In a “information pooling”). However, the vertical rela-

pilot run, the platform posted the following challenge: tionship between the platform and its participants

“how can access to information and services provided tends to exhibit more reciprocal interdependence.

by UNHCR and partners be improved for refugees Benchmarking platforms often create reporting require-

and people of concern residing in urban areas?” The ments for their participants. And once the platform has

Web site allowed these participants to submit and vote pooled this information, it often provides feedback to

on ideas and to post comments on online discussions. participants about their individual and collective per-

Although crowdsourcing can be more interactive than formance. They may also provide central knowledge

many traditional consultation techniques, creating and support to help participants improve their per-

some opportunity for collaboration, crowdsourcing formance over time. The Organization for Economic

interactions do not generally represent full-fledged Co-operation and Development (OECD) has exten-

collaborative governance (e.g., collective decision- sively used benchmarking as a strategy for encouraging

making processes that are formal, deliberative and improvements in national performance (Groenendijk

consensus-oriented). 2009). Benchmarking platforms are not necessarily

Knowledge and benchmarking platforms suggest forms of collaborative governance either, though they

somewhat greater vertical interdependence between often have more elements of collaboration than know-

platforms and their constituents than does crowd- ledge or crowdsourcing platforms. For example, the

sourcing. Knowledge platforms exercise a clearing- concept of “democratic experimentalism,” as devel-

house function, collecting relevant knowledge from oped by Sabel and Zeitlin (2010), combines bench-

constituents and disseminating it back to those same marking with elements of collaborative governance.

constituents. The International Atomic Energy Agency The process of establishing goals, specifying reporting

(IAEA), for example, fosters the creation of web-based requirements, and evaluating performance is under-

National Nuclear Safety Knowledge Platforms “for stood to be a multilateral and deliberative process.

sharing reference information”; these platforms “can Figure 1 describes crowdsourcing, knowledge and

serve national, regional, and global stakeholders as benchmarking platforms as representing increasingly

an authoritative source of information, maintained stronger design rules. The intermediary role of all

directly by the respective Member State.”5 Although three, however is often limited to pooling or aggregat-

this clearinghouse role does not require elaborate ing constituent inputs. A network-of-networks plays a

collaborative intermediation between participating more extensive intermediating role without imposing

groups, the IAEA does envision that these knowledge extensive design rules. The meta-network intermedi-

ates between existing networks while limiting interven-

5 https://gnssn.iaea.org/main/Pages/NationalPlatforms.aspx/ accessed tion into member networks. The World Social Forum,

November 30, 2016. for example, creates a neutral space for a variety of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

28 Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1

anti-globalization social movements (Patomäki and standards themselves and the certification process can

Teivainen 2004). To prevent divisiveness, however, the be understood as well-articulated design rules specify-

Forum scrupulously avoids taking any collective pos- ing what participants must do in order to participate

ition itself. This neutrality is a critical design rule, but in the platform. Collaboration may enter in two ways.

few other rules are imposed. Another example is the First, the standards themselves are often set through a

United Kingdom’s Communities and Climate Action collaborative process. Second, stakeholders must often

Alliance Network (CCAA), which explicitly describes engage in a collaborative process to meet the stand-

itself as a “network of networks.”6 The Network fos- ards. For example, the Marine Stewardship Council

ters collaboration among a number of networks work- (MSC) is a program that certifies sustainable fisher-

ing on climate change and energy issues, including ies. It has established a sustainable fisheries standard

networks like the Low Carbon Communities Network, that includes three core principles and 28 performance

the Transition Network, and the Scottish Communities indicators. These standards are understood by MSC to

Climate Action Network. CCAA describes itself as an be benchmarks that represent international best prac-

“informal grouping of representatives from networks tices for sustainable fisheries management. However,

that support grass roots action” with a “light touch the MSC goes beyond voluntary reporting and pool-

secretariat” and where “[e]ach network member takes ing of performance information, since participants

responsibility to communicate with its own network.” receive the MSC “blue label” only if they are certified

As this description suggests, the CCAA is a collabora- by a third-party certifier. The MSC itself is a non-profit

tive platform, but its role in promoting is restricted to international organization governed with collaborative

intermediating between the component networks. input provided through a formal stakeholder council.

Matching platforms exhibit limits on collaboration Although the MSC provides technical and institu-

in a different sense. Air BnB has popularized the idea tional support to fisheries that wish to be certified and

of platforms that promote peer-to-peer sharing. Such encourages them to work in a collaborative fashion, it

platforms help match people who have something to does not play a major role in intermediating collabor-

sell or contribute with someone who is looking to buy ation at the fishery level.7

or is in need of something. Whether self-interested Bridging organizations typically play a strong cata-

or gifted, these relationships tend to be bilateral lytic role in promoting collaboration while imposing

exchanges. They depend upon the platform to identify minimal design rules on participating stakeholders

and facilitate the exchange, but vertical coordination (Brown 1991). A good example is the Ecomuseum

with the platform is otherwise quite limited. The plat- Kristianstads Vattenrike (EKV), a Swedish organiza-

form’s role is to intermediate the bilateral exchange. tion that serves as an important bridging organization

Matching platforms are now being experimented with in an effort to preserve environmental and cultural val-

as a governance strategy. For example, Global Hand ues associated with a large wetland. The organization

describes itself as “a matching service” for aligning is the center node in a wider network of “collabora-

available donor resources with humanitarian and tive learning projects” encouraged or initiated but not

development needs. Run by a Hong Kong-based inter- administered by EKV (Hahn et al. 2006, 581). EKV

national NGO, the Crossroads Foundation, Global does exert some control over these projects through

Hand actually goes beyond a narrow matching role the initiation of projects and the selection of partici-

to play a more significant role in promoting collab- pants. However, most of EKV’s energy is spent on

oration, describing itself as “…a non-profit brokerage strategically identifying “win-win” strategies, on trust

facilitating public/ private partnership” (http://www. and consensus-building, and on linking local projects

globalhand.org/, accessed December 3, 2016; see also to extra-local institutions and funders. In other words,

Ogelsby and Burke 2012 and Lee and Restrepo 2015). EKV is actively engaged in projects, but its role can be

Standardization or certification platforms tend described as primarily intermediation rather than con-

to create strong design rules while playing a modest trol. Nevertheless, it has successfully initiated over 200

intermediating role. These platforms establish stand- local projects.

ards that participants then adopt—typically volun- We find that many of the platforms that best fit

tarily. In some cases, these platforms also certify that our description of collaborative platforms exert more

participants have adequately met the standards in control over the design rules than does the EKV. We

question, often by relying on third-party certifiers. The call one version of these institutions franchise plat-

forms because they tend to create a basic framework

or technology for collaborative governance and then

6 https://ccaanet.wordpress.com/current-activities/ accessed Nove replicate this in different places in a manner similar to

mber 8, 2016. The Roundtable on the Crown of the Continent (table 1)

has also been described as a “network of networks” (Wyborn and

Bixler 2013). 7 https://www.msc.org/ accessed December 3, 2016.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/28/1/16/4372135

by Adam Ellsworth, Adam Ellsworth

on 14 December 2017

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2018, Vol. 28, No. 1 29

commercial franchises. By controlling the design of the they sought to break political stalemates and man-

basic collaborative framework and then replicating it, age pressing problems. The first generation of schol-

these collaborative platforms facilitate the scaling up arship on collaborative governance focused on how

of collaboration. The three examples that we began the these local and reactive efforts have worked in prac-

article by describing all appear to be, to a greater or tice. Increasingly, however, collaborative governance

lesser degree, franchise platforms: EPODE promotes is being viewed as a more global and proactive pol-

a basic social marketing technology around which icy instrument, one that can be deployed on a larger

local collaborative anti-obesity campaigns are organ- scale and extended from one local context to another.

ized; the CTC promotes local collaboration around the Although we know a good deal about specific instances

basic module of a marine reserve; and EADD replicates of collaborative governance, we know much less about

its basic “hub” concept in different farm communities. treating collaborative governance as a generic policy

Local anti-obesity campaigns, marine reserves, and instrument.

dairy hubs are franchises that establish or promote We have argued that the concept of platforms is

certain basic design principles while allowing for local one way to think about how collaborative governance

customization via collaborative governance. is being promoted and facilitated as a generic policy

Finally, functional modular platforms exercise both instrument. Building on an organization-theoretic

a strong intermediary role and strong design control understanding of platforms, the concept is used here

and are understood here to be analogous to what the to refer to a relatively stable organizational framework

platform literature calls technological platforms, such upon which multiple shorter-term or more specialized

as those characterizing automotive platforms. The projects or networks can be built. These collaborative

modular components of this kind of platform must be platforms help to facilitate “many-to-many” (multilat-

able to easily interface with the platform and then work eral) collaborative relationships.

as part of a functional whole. This systemic functional- Beyond describing how collaborative platforms are

ity requires a strong degree of design control over the being used to scale up or deepen collaborative gov-

modular units. We found few examples of collabora- ernance, the theoretical goal of the article has been

tive platforms with this type of functional modularity. to expand the use of the platform concept beyond

However, the California water collaborative known as IT and into public administration and governance.

CALFED comes close. Although it has been superseded Platforms exhibit organizational properties that are as

by new initiatives, while it existed CALFED estab- yet poorly understood, but which are potentially valu-

lished a collaborative platform that facilitated and able for understanding how the public sector copes

guided many different smaller collaborative projects. with demands to balance stability and change. As sta-

As described by Booher and Innes, CALFED consisted ble frameworks upon which more flexible organizing

of a “shifting set of diverse ad hoc task groups” organ- frameworks can be built, platforms are seen as recon-

ized under the auspices of a central policy committee figurable—that is, they may be flexibly organized and

(Booher and Innes 2010, 5). According to Booher and reorganized to meet changing needs. Reconfigurability

Innes, these groups understood that they were part of is often facilitated by the modularity of platforms,

a larger functioning system: which allows peripheral “modules” to be plugged in to

the core platform in a customized way. Platforms are

Participants understood that there must be bal-

often designed to enable heterogenous and highly dis-

ance and linkages among projects to keep all

tributed action and to integrate highly variable com-

stakeholders at the table. Most understood that

ponent parts. When these ideas of reconfigurability,

they needed to support the whole package and,

modularity, and high variability are combined, plat-

thus, the whole system, if they were to get what

forms are said to be evolvable, meaning that they are

they needed (Booher and Innes 2010, 6).

adaptable to changing external conditions and respon-

Booher and Innes describe how this water planning sive to feedback from their own activities. Positive

and management institution was coordinated by “col- feedback effects are regarded as critical mechanisms of

laborative interaction heuristics” that they refer to col- platform evolution.

lectively as the “CALFED way.” In exploring how these general ideas might apply

to collaborative platforms, we have been struck by the

importance of intermediation for managing many-to-

Conclusion many collaborative relationships. Collaborative plat-

Much of the early development of collaborative gov- forms typically have limited coercive authority and this

ernance has been local and reactive in nature. Public capacity to align and arbitrate the action of different