Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Paulsen 2014

Uploaded by

MOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERACopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Paulsen 2014

Uploaded by

MOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERACopyright:

Available Formats

VOLUME 32 䡠 NUMBER 29 䡠 OCTOBER 10 2014

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY O R I G I N A L R E P O R T

Efficacy of Methylprednisolone on Pain, Fatigue, and Appetite

Loss in Patients With Advanced Cancer Using Opioids:

A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial

Ørnulf Paulsen, Pål Klepstad, Jan Henrik Rosland, Nina Aass, Eva Albert, Peter Fayers, and Stein Kaasa

See accompanying editorial on page 3210; listen to the podcast by Drs Vardy and Agar at

Ørnulf Paulsen, Telemark Hospital www.jco.org/podcasts

Trust, Skien; Ørnulf Paulsen, Pål Klep-

stad, Peter Fayers, and Stein Kaasa, A B S T R A C T

Norwegian University of Science and

Technology; Pål Klepstad and Stein

Purpose

Kaasa, St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim

Corticosteroids are frequently used in cancer pain management despite limited evidence. This

University Hospital, Trondheim; Jan

Henrik Rosland, Haraldsplass Deacon-

study compares the analgesic efficacy of corticosteroid therapy with placebo.

ess Hospital and University of Bergen,

Bergen; Nina Aass, Oslo University

Patients and Methods

Hospital and University of Oslo, Oslo;

Adult patients with cancer receiving opioids with average pain intensity ⱖ 4 (numeric rating scale

Eva Albert, Sørlandet Hospital Kris- [NRS], 0 to 10) in the last 24 hours were eligible. Patients were randomly assigned to methylpred-

tiansand, Kristiansand, Norway; and nisolone (MP) 16 mg twice daily or placebo (PL) for 7 days. Primary outcome was average pain

Peter Fayers, University of Aberdeen, intensity measured at day 7 (NRS, 0 to 10); secondary outcomes were analgesic consumption (oral

Aberdeen, United Kingdom. morphine equivalents), fatigue and appetite loss (European Organisation for Research and Treatment

Published online ahead of print at of Cancer–Quality of Life Questionnaire C30, 0 to 100), and patient satisfaction (NRS, 0 to 10).

www.jco.org on July 7, 2014.

Results

Supported by unrestricted grants from

A total of 592 patients were screened; 50 were randomly assigned, and 47 were analyzed. Baseline opioid

the Telemark Hospital Trust and the

South-Eastern Norway Regional Health

level was 269.9 mg in the MP arm and 160.4 mg in the PL arm. At day-7 evaluation, there was no difference

Authority. between the groups in pain intensity (MP, 3.60 v PL, 3.68; P ⫽ .88) or relative analgesic consumption (MP,

1.19 v PL, 1.20; P ⫽ .95). Clinically and statistically significant improvements were found in fatigue (⫺17 v

Presented in abstract form and orally at

the 13th World Congress of the Euro-

3 points; P .003), appetite loss (⫺24 v 2 points; P ⫽ .003), and patient satisfaction (5.4 v 2.0 points; P ⫽ .001)

pean Association for Palliative Care, in favor of the MP compared with the PL group, respectively. There were no differences in adverse effects

Prague, Czech Republic, May 30-June between the groups.

2, 2013, and as a poster at the 2013

European Cancer Congress, Amster- Conclusion

dam, the Netherlands, September MP 32 mg daily did not provide additional analgesia in patients with cancer receiving opioids, but

28-October 1, 2013. it improved fatigue, appetite loss, and patient satisfaction. Clinical benefit beyond a short-term

The study sponsors had no role in the effect must be examined in a future study.

planning of the study, study design,

collection of data, analysis or interpreta- J Clin Oncol 32:3221-3228. © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology

tion of data, writing of the report, or deci-

sion to submit the report for publication.

the adjuvant pain medications, according to the

Terms in blue are defined in the glos- INTRODUCTION

sary, found at the end of this article

treatment guidelines.4-7

and online at www.jco.org. Pain is a prevalent symptom in patients with can- Inflammation is a significant pain-modulating

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts cer,1 and providing pain relief is a challenge. Cancer factor. Proinflammatory cytokines and chemo-

of interest and author contributions are pain is complex, involving inflammatory, neuro- kines can directly modulate neuronal activity in

found at the end of this article.

pathic, ischemic, and compression mechanisms.2 both the peripheral and CNSs.8 Glia cells play a

Clinical trial information: NCT00676936;

Pain may be caused by a mixture of these mecha- major role in pain regulation, in part by releasing

EudraCT 2007-005617-19.

nisms in the individual patient, occurring at multi- proinflammatory cytokines.9 Corticosteroids are

Corresponding author: Ørnulf Paulsen,

MD, Telemark Hospital Trust, Palliative

ple sites and changing over time.2 potentanti-inflammatorydrugs,inhibitarangeofpro-

Care Unit, Ulefossveien, N-3710 Skien, Careful assessment of pain and titration of inflammatory molecules,10 and are recommended

Norway; e-mail: ornulf.paulsen@sthf.no. nonopioid and opioid analgesics comprise the basis therapy as an adjunct for postoperative pain.11 In

© 2014 by American Society of Clinical of cancer pain treatment. In addition, the WHO and two randomized trials, analgesic effect in patients

Oncology

European Association for Palliative Care pain man- with cancer was reported.12,13 Corticosteroids can

0732-183X/14/3229w-3221w/$20.00

agement recommendations state that adjuvant pain also mediate pain relief by reducing tumor-related

DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.3926 medications should be considered at each step of the edema in brain metastases14 or by directly reducing

WHO analgesic ladder.3 Corticosteroids are one of tumor burden (eg, in prostate cancer).15

© 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology 3221

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Paulsen et al

Corticosteroids are used in a large proportion of patients with metastases. Production of study drugs was performed at the hospital pharmacy

cancer pain. A European survey of 3,030 patients admitted to palliative at the Telemark Hospital Trust. Randomization was blinded for all parties

until the completion of data collection.

care programs showed that 39% used corticosteroids.1 A Swedish

survey showed that 50% of patients with cancer in palliative care Intervention

received corticosteroids, and pain was the indication for treatment in After baseline assessment, patients received identical-looking capsules of

the study drug containing either methylprednisolone 16 mg or placebo twice

25% of the cases.16 However, in a recently published systematic liter- daily for 7 days. Patients were contacted daily by a study nurse during the

ature review, we found little evidence for an analgesic effect of corti- treatment period to ensure compliance with the protocol.

costeroids in the treatment of cancer pain.17 This review calls into

Instruments

question the widespread use of corticosteroids for cancer pain.17 Medical and sociodemographic data. Patient demographics, medica-

The most common indications for starting corticosteroids in the tions, clinical characteristics, and pain categories, as judged by clinical evalua-

Swedish survey were appetite loss (37%), fatigue (36%), and poor tion, were recorded at baseline (Table 1). Daily analgesic consumption, which

well-being (33%).16 An expert working group of the European Asso- was a secondary outcome in the trial, was recorded in a diary and converted to

oral morphine equivalents.20

ciation for Palliative Care stated that steroids might be effective in Symptom assessment. Primary end point was average pain intensity

relieving fatigue for a short period of time, but the documentation was (NRS, 0 [no pain] to 10 [worst imaginable pain]), as measured by the Brief

weak.18 A systematic review of the treatment of cancer-associated Pain Inventory21 at day 7. Secondary outcomes were daily pain intensity at rest

anorexia and weight loss reported evidence to support the use of measured by the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (NRS, 0 to 10),

corticosteroids in short courses as an appetite stimulant.19 reported as area under the curve22; change in fatigue and appetite loss from

Against this background, we performed a randomized controlled

trial with the primary aim of comparing the analgesic effects of oral

methylprednisolone 32 mg with placebo administrated for 7 days in Table 1. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Inclusion (N ⫽ 49)

patients with cancer pain using opioids. Secondary aims were to eval- Methylprednisolone Placebo

(n ⫽ 26) (n ⫽ 23)

uate the effects of corticosteroids regarding fatigue, appetite loss, sat-

isfaction with treatment, and tolerance of this medication. Characteristic No. % No. %

Sex

Female 13 11

PATIENTS AND METHODS Male 13 12

Age, years

Mean 62.5 66.0

Study Design

95% CI 59.0 to 65.9 60.8 to 71.2

The study was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-

Karnofsky score (0 to 100)

group, multicenter phase III trial of oral corticosteroids in patients with cancer

Mean 66.4 65.7

experiencing pain. The trial was conducted according to Good Clinical Prac-

95% CI 60.8 to 72.2 59.7 to 71.6

tice guidelines, monitored independently by staff members from Oslo Univer-

Cancer diagnosis

sity Hospital, and registered in ClinicalTrial.gov on May 8, 2008. The study was

Breast 1 4 1 5

approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and Nor-

Prostate 3 12 3 14

wegian Directorate of Health. The procedures were conducted in accordance

GI 6 23 5 23

with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 1983. The technical appendix,

Lung 6 23 5 23

statistical code, and complete anonymized data set are available from the

Gynecologic 5 19 5 23

corresponding author.

Other 7 27 4 18

Patients Metastasis

Patients with cancer, age ⱖ 18 years with average pain ⱖ 4 (numeric No 1 4 1 5

rating scale [NRS], 0 to 10) in the last 24 hours, with ⬎ 4 weeks expected Liver 11 42 6 27

survival and receiving an opioid for moderate or severe cancer pain, were CNS 2 8 0 0

eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: excruciating pain Bone 9 35 6 27

(average pain NRS ⱖ 8 in last 24 hours), use of corticosteroids in the last 4 Lung 4 16 3 14

weeks, diabetes mellitus, peptic ulcer disease, concurrent medication with Other 15 58 18 82

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, radiotherapy or systemic cancer treat- Mini Mental State Examination score

ment started ⬍ 4 weeks before entering the study or planned to start within the Mean 27.1 27.0

study period, spinal cord compression or need of bone surgery, and severe Concomitant disease

cognitive impairment. No changes in the current scheduled opioid medication Total 16 62 13 59

were allowed for the last 48 hours before inclusion or throughout the study Cardiac 4 16 4 18

period. Patients could use additional opioid for breakthrough pain. In- and Vascular 5 19 8 36

outpatients were screened for participation at five palliative care units and Lung 3 12 4 18

outpatient oncology services in Norway: Telemark Hospital, Haraldsplass GI/hepatic 4 16 1 5

Deaconess Hospital, Sørlandet Hospital, St Olav’s University Hospital, and Other 8 31 10 43

Oslo University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained before any Ongoing cancer treatment

study-related procedures were performed. Radiotherapy 0 0 0 0

Chemotherapy 4 16 3 14

Randomization and Masking Hormonal therapy 3 12 3 14

Computerized randomization was provided by Norwegian University of None 19 73 17 77

Science and Technology by personnel not otherwise involved in the study.

Randomization was stratified for study center and pain related to verified bone

3222 © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Methylprednisolone RCT for Cancer Pain, Fatigue, and Appetite Loss

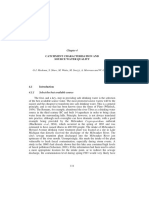

Assessed for eligibility

(N = 592)

Not eligible (n = 542)

Not meeting inclusion criteria (n = 60)

Declined to participate (n = 13)

Exclusion criteria (n = 462)

Receiving corticosteroids (n = 169)

Systemic cancer treatment (n = 125)

Pain ≥ 8 (n = 33)

Opioid dose change last 48 hours (n = 19)

Diabetes mellitus (n = 30)

Cognitive impairment (n = 11)

Other exclusion criteria (n = 75)

Other reasons (n = 7)

Randomly allocated

(n = 50)

Allocated to methylprednisolone (n = 26) Allocated to placebo (n = 24)

Received methylprednisolone (n = 26) Received placebo (n = 23)

Did not receive methylprednisolone (n = 0) Did not receive placebo (n = 1)

(patient withdrew consent before any study

procedures were done)

Lost to follow-up (n = 0) Lost to follow-up (n = 0)

Discontinued methylprednisolone (n = 1) Discontinued placebo (n = 1)

(SAE, withdrawn day 5 as a result of malignant (SAE, patient died day 4 as a result of

bowel obstruction) disease progression)

Analyzed (n = 25) Analyzed (n = 22)

Excluded from analysis (n = 0) Excluded from analysis (n = 0)

(1 patient SAE, withdrawn day 5, received

methylprednisolone, kept in analysis)

Fig 1. CONSORT flow diagram. SAE, serious adverse effect.

baseline to day 7, both measured by the European Organisation for Research SPSS statistical software (versions 15.0 and 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used

and Treatment of Cancer–Quality of Life Questionnaire C3023; and overall for all statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed according to

satisfaction with the intervention (NRS, 0 [no benefit] to 10 [major benefit]) intention-to-treat principles.

measured at day 7. Fatigue and appetite loss scores were calculated according

to guidelines,24 with scores ranging from 0 to 100; a higher score represented a

higher level of symptoms (ie, worse). A difference of 10, corresponding to 1 on RESULTS

the NRS (0 to 10) scales, was considered clinically significant.25

Adverse effects. The presence of adverse effects (AEs) was assessed by the Study Population

investigator at day 7 through semistructured interviews (presence of edema, A total of 592 patients with cancer and average pain intensity ⱖ 4

sleeplessness, restlessness, anxiety, muscle weakness, psychological changes, in the last 24 hours were identified and screened for eligibility at five

dyspepsia, mouth symptoms, and other [yes v no]). The complete protocol is

available at http://www.ntnu.edu/prc/projects.

outpatient oncology services and palliative care programs. Fifty pa-

tients were recruited during the period from April 2008 to January

Statistical Analysis 2012. The reasons for excluding patients are shown in Figure 1. The

The trial was designed to detect a difference in average pain intensity of

two treatment groups had some minor differences in characteristics at

1.5 (NRS, 0 to 10) between the intervention and placebo groups measured at

day-7 evaluation.26 With a standard deviation of 1.5,12 two-sided t test, baseline (Tables 1 and 2). These were corrected for in the data analyses.

power of 0.90, and significance level of .05, the estimated sample size was 22 Three patients did not complete the study period: one withdrew con-

evaluable patients in each group. A total of 50 patients were recruited to sent before any study procedures were performed, one died as a result

allow for dropouts. of disease progression, and one was withdrawn because of malignant

All data are reported as means, 95% CIs, ranges, medians, or frequencies bowel obstruction. In addition, one patient was withdrawn because of

as appropriate. In the comparison between the two groups, the independent rapidly increasing back pain at day 5. This patient received methyl-

student’s t test was used for continuous variables. In addition, regression and

covariate analyses were performed to adjust for pain intensity and other

prednisolone 48 mg daily on an open basis because of clinical suspi-

differences between the groups at baseline, with the stratification factor of pain cion of spinal cord compression. The patient remained in the analysis,

related to verified bone metastasis and study center. Mann-Whitney U test was according to the principles of the intention-to-treat analysis. No pa-

used for noncontinuous variables. A P value ⱕ .05 was defined as significant. tients were withdrawn or discontinued the study because of AEs.

www.jco.org © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology 3223

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Paulsen et al

Treatment effect on fatigue, appetite loss, and overall satisfaction.

Table 2. Pain Characteristics and Pain Medication at Inclusion (N ⫽ 49)

At day 7, there were significant improvements in fatigue and appetite

Methylprednisolone Placebo loss in the corticosteroid group compared with the placebo group.

(n ⫽ 26) (n ⫽ 23)

Reported as change from baseline, fatigue improved 17 points (95%

Characteristic No. % No. % CI, ⫺27 to ⫺6) in the corticosteroid arm versus a deterioration of 3

Pain category points (95% CI, ⫺5 to 11) in the placebo group (P ⫽ .003). Appetite

Bone 6 23 5 23 improved 24 points (95% CI, ⫺38 to ⫺11) in the corticosteroid group

Visceral 11 42 9 41

versus a deterioration of 2 points (95% CI, ⫺8 to 11) in the placebo

Soft tissue 1 4 6 27

Neuropathic 5 19 1 5

group (P ⫽ .003). Regression analyses using the same variables as for

Mixed 3 12 2 9 pain intensity did not change the results (data not shown). Overall

Breakthrough pain 14 54 17 77 satisfaction with treatment was significantly higher in the corticoste-

Opioids roid group compared with the placebo group (5.4; 95% CI, 4.1 to 6.7 v

Morphine 8 31 7 32 2.0; 95% CI, 0.7 to 3.3; P ⫽ .001; Table 3; Fig 2).

Oxycodone 9 35 10 45

AEs. There were no differences between number of AEs in the

Fentanyl 7 27 6 27

Other 2 8 0 0

corticosteroid group compared with the placebo group (average number,

Oral morphine equivalents 1.08; 95% CI, 0.52 to 1.64 v 1.55; 95% CI, 0.85 to 2.24, respectively; P ⫽

(mg per day) .28; Table 4). The most frequent AEs were oral symptoms, restlessness,

Mean 269.9 160.3 and sleeplessness. The two latter were more frequent in the corticosteroid

95% CI 168.0 to 371.8 90.2 to 230.5 group (restlessness, six v three; sleeplessness, four v three). Three serious

Nonopioids

AEs were reported during the treatment period: one in the placebo group,

Paracetamol 22 85 22 100

Pregabalin 3 12 3 14

whereapatientdiedatday4becauseofdiseaseprogression,andtwointhe

Gabapentin 6 23 0 0 corticosteroid group, where one patient was withdrawn on day 5 because

Amitriptyline 1 4 2 9 of malignant bowel obstruction, and another was withdrawn on day 5

Ketamine 1 4 0 0 because of clinical suspected spinal cord compression. None of these were

suspected to have been caused by the study medication.

DISCUSSION

Twenty-five patients were evaluable in the corticosteroid group, and

22 patients in the placebo group (Fig 1). This study found no evidence of any additional analgesic effect of meth-

ylprednisolone 32 mg daily for 7 days in patients with advanced cancer

Efficacy Analyses treated with opioids. Patients receiving corticosteroids reported less fa-

Treatment effect on pain relief. At day 7, there were no differences tigue, better appetite, and better overall satisfaction with the treatment

in average pain intensity (mean difference, ⫺0.08; 95% CI, ⫺0.97 to compared with the placebo group. The medication was well tolerated.

1.13; corticosteroid arm, 3.6; 95% CI, 2.8 to 4.4; placebo arm, 3.7; 95% The evidence for analgesic effects of corticosteroids in patients

CI, 3.0 to 4.4; P ⫽ .88). Similarly, there were no significant differences with cancer was recently evaluated in a systematic literature review

in pain intensity between the groups when measured as change from published by our research group.17 Four randomized controlled trials

baseline (⫺0.48; 95% CI, ⫺1.43 to 0.47; corticosteroid arm, ⫺1.16; were identified, but only one of these performed an adequate assess-

95% CI, ⫺1.96 to ⫺0.35; placebo group, ⫺0.68; 95% CI, ⫺1.28 to ment of outcomes,12 and the quality of evidence was rated low. Ac-

⫺0.08; P ⫽ .50; Table 3; Fig 2). Correcting for differences between cordingly, only a weak recommendation was made: “Evidence

groups in baseline pain intensity, allowing for covariates, reduced the supports that a moderate dose of corticosteroid, such as methylpred-

difference between the groups to ⫺0.33 (95% CI, ⫺1.33 to 0.67). nisolone 32 mg, may contribute to analgesia and seems to be well

There were no differences between the groups concerning opioid tolerated.”17(p104) In addition, concern about serious AEs associated

consumption. The opioid dose increased similarly in both groups with continued high-dose treatment with corticosteroids was raised.

(relative consumption day 7 v day 0: corticosteroid arm, 1.19; 95% CI, In a cross-over study by Bruera et al,12 a difference in pain inten-

1.00 to 1.38; placebo arm, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.51; P ⫽ .95; Table 3; sity of 13 (visual analog scale, 0 to 100) in favor of the corticosteroid

Fig 3). Daily registrations of pain intensity at rest (area under curve) period compared with the placebo period was found (CIs not pro-

were also similar between the study groups (Table 3). vided). The intervention was similar to that in our study: methylpred-

Regression analyses were also performed adjusting for differ- nisolone 16 mg twice daily. However, the two studies differ in some

ences in baseline characteristics between the groups (Tables 1 and 2): respects. In our study, patients used on average 222 mg oral morphine

baseline opioid dose, presence of breakthrough pain, use of gabapen- equivalents at baseline, had advanced cancer disease, and a mean

tin or pregabalin, soft tissue pain, liver metastases, and other metasta- Karnofsky performance score of 66, approximately equal to an Eastern

ses. Regression analyses did not change the results. Interactions of Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2.27 In the study

treatment with pain categories and cancer type were explored using by Bruera et al, the 28 evaluated patients used propoxyphene equaling

linear regression analyses and showed no evidence of important inter- approximately 36 mg of oral morphine equivalents,28 and patients had

actions; the  coefficients for medication and for the main effects of a mean Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of

the prognostic factors were substantially unchanged when the inter- 3.5. This indicates that the two studies represent two different cancer

action terms were included and excluded from the model. pain populations.

3224 © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Methylprednisolone RCT for Cancer Pain, Fatigue, and Appetite Loss

Table 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Methylprednisolone Placebo

(n ⫽ 25) (n ⫽ 22)

Outcome Mean 95% CI Mean 95% CI Pⴱ

Average pain intensity†‡

Day 0 4.76 4.33 to 5.19 4.36 3.88 to 4.85 .21

Day 7 3.60 2.79 to 4.41 3.68 2.99 to 4.37 .88

Mean difference ⫺1.16 ⫺1.96 to ⫺0.35 ⫺0.68 ⫺1.28 to ⫺0.08 .50

Morphine consumption (OMEs), mg§

Day 0 273.8 167.8 to 379.8 165.8 93.1 to 238.5 .09

Day 7 318.6 192.3 to 444.8 188.2 103.2 to 273.2 .08

Mean difference 44.8 ⫺16.0 to 105.6 22.4 ⫺5.6 to 50.4 .51

Relative difference (day 7/day 0) 1.19 1.00 to 1.38 1.20 0.90 to 1.51 .95

Pain intensity at rest (day 1 to 7)‡§储

AUC 19.9 14.4 to 25.4 17.9 12.2 to 23.6 .60

Fatigue§储¶

Day 0 77.1 68.3 to 85.9 67.2 56.3 to 78.1 .15

Day 7 60.4 49.7 to 71.2 70.5 61.4 to 79.6 .16

Mean difference ⫺16.7 ⫺27.0 to ⫺6.3 3.3 ⫺4.5 to 11.1 .003

Appetite loss§储¶

Day 0 73.3 60.2 to 86.5 63.6 50.8 to 76.5 .28

Day 7 49.3 34.9 to 63.7 65.2 51.9 to 78.4 .10

Mean difference -24.0 ⫺37.5 to ⫺10.5 1.5 ⫺8.1 to 11.2 .003

Patient satisfaction with treatmentठ5.4 4.05 to 6.70 2.0 0.71 to 3.29 .001

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; OME, oral morphine equivalent.

ⴱ

t test.

†Primary outcome.

‡Numeric rating scale, 0 to 10.

§Secondary outcome.

储Higher score in symptom assessment represents higher level of symptom (ie, worse).

¶Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, 0 to 100.

We observed a beneficial effect from corticosteroids on appetite with fatigue as the primary end point. Participants were outpa-

loss and fatigue. A Cochrane review from 2010 found no research tients with advanced cancer. The study demonstrated a significant

on corticosteroids with fatigue as the primary outcome.29 In 2013, improvement of 5.9 points (Functional Assessment of Chronic

Yennurajalingam et al30 published a randomized controlled trial Illness Therapy–Fatigue subscale, range, 0 to 52) in the corticosteroid

10 100 10

Day 0 Day 0 Day 0

Day 7 Day 7 Day 7

9 90 9

P = .50 P = .003 P = .003 P = .001

8 80 8

7 70 7

No. of Patients

No. of Patients

No. of Patients

6 60 6

5 50 5

4 40 4

3 30 3

2 20 2

1 10 1

0 0 0

CS PL CS PL CS PL CS PL

Average Pain Intensity Fatigue Appetite Patient Satisfaction

Fig 2. Main results: average pain intensity in last 24 hours (numeric rating scale [NRS], 0 to 10), fatigue and appetite (European Organisation for Research and

Treatment of Cancer–Quality of Life Questionnaire C30, 0 to 100) on days 0 and 7, and patient satisfaction (NRS, 0 to 10) on day 7. CS, corticosteroid; PL, placebo.

www.jco.org © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology 3225

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Paulsen et al

These effects may, in long-term use, counteract the positive effects on

Analgesic consumption CS Analgesic consumption PL

fatigue and appetite. Indeed, the trial by Bruera et al indicated that the

Pain now CS Pain now PL

appetite-stimulating effect of corticosteroids diminishes over time.

350 10 This underlines the need for larger long-term studies. Nevertheless,

(mean oral morphine equivalents)

9 the reported results support a short-term trial of corticosteroids in

Mean Analgesic Consumption

300

8

patients with cancer-related fatigue or loss of appetite.

Pain Intensity at Rest

To our knowledge, ours is the first randomized, controlled,

250 7

double-blind study investigating the analgesic properties of corticoste-

200

6 roids in a population of patients with advanced cancer using opioids.

5 Although the majority of patients included had metastatic disease, the

150 number of dropouts and amount of missing data were low. All out-

4

comes for pain intensity and analgesic consumption showed in a

100 3 consistent way that there were no differences between the intervention

2 and control groups. It was known that a large proportion of the patient

50 group screened already used corticosteroids or had received systemic

1

cancer treatment. Therefore, it was necessary to screen a large number

0 0 of patients to reach the target of 50 eligible patients. The recruitment

0

period was 45 months. This may have introduced a possible selection

ay

ay

ay

ay

ay

ay

ay

ay

D

bias. The corticosteroid group had higher levels of pain intensity,

Fig 3. Mean analgesic consumption and pain intensity at rest (numeric rating morphine consumption, fatigue, and loss of appetite at baseline com-

scale, 0 to 10) as measured day by day. CS, corticosteroid; PL, placebo.

pared with the placebo group, although none of these differences were

statistically significant. Regression analyses did not change the results.

Our trial did not show any analgesic effects from corticosteroids.

group receiving dexamethasone 4 mg twice daily compared with the

The small sample size is reflected by the wide 95% confidence limits.

placebo group. The improvements were significant after both 8 and 15

However, the clinical difference of interest was above the upper bound

days. Both the corticosteroid doses used as well as the results demon-

of the 95% CI, which confirms that there is unlikely to have been a

strated are comparable to the findings in our study. Several randomized

clinically useful effect. The outcomes of fatigue and appetite loss showed

controlled trials have demonstrated a short-term positive effect on appe-

bothclinicallyandstatisticallysignificantimprovement.Thissuggeststhat

tite loss12,13,30-33; only one study did not demonstrate this effect.34

the lack of analgesic effect in the study was not a small-sample effect and

The number of AEs was low in our study, with no difference

supports the main conclusion. However, the sample size was too small to

between the two groups. This finding coincides with the studies by

perform a subgroup analysis, which could have been of clinical interest.

Bruera et al12 and Yennurajalingam.30,34 It is generally agreed that

Lack of analgesic effect in the this study should not preclude the

corticosteroid toxicity is related to the total cumulative dose of corti-

use of corticosteroids in cancer pain syndromes where specific mech-

costeroids as well as the duration of their use.7,35 AEs accumulate with

anisms of action from these drugs are effective. Examples of such

long-term use, and development of cushingoid habitus with moon

mechanisms are reduction of edema in patients with cerebral metas-

face and skin atrophy, osteoporosis, hyperglycaemia, increased risk of

tases and tumor reduction in patients with lymphoma.

infection, and neuropsychological effects36 may interfere with health-

In conclusion, our study found no evidence of an analgesic effect

related quality of life in this patient group. Furthermore, corticoste-

of methylprednisolone 32 mg daily in patients with advanced cancer

roids are known to promote muscle atrophy37,38 and myopathy.39

treated with opioids. Thus, this study provides no support for cancer

pain in general as an indication for starting treatment with corticoste-

roids. Patients who received corticosteroids had clinically significant

Table 4. AEs reduced fatigue and increased appetite, as well as a significantly higher

Methylprednisolone Placebo level of treatment satisfaction, suggesting a symptomatic benefit from

(n ⫽ 25) (n ⫽ 22) the treatment. Clinical benefit beyond short-term effects must be

Predefined AE Category No. % No. % examined in a future study.

Oral symptoms 6 24 7 32

Restlessness 6 24 3 14

Psychic change 2 8 3 14 AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS

Anxiety 2 8 3 14 OF INTEREST

Edema 1 4 5 23

Muscle weakness 1 4 3 14 The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Sleeplessness 4 16 3 14

Dyspepsia 3 12 4 18

Other 2 8 3 14 AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Total 27 34

Mean No. of AEs 1.08 1.55

P .28

Conception and design: Ørnulf Paulsen, Pål Klepstad, Peter Fayers,

Stein Kaasa

Abbreviation: AE, adverse effect. Financial support: Ørnulf Paulsen

Administrative support: Ørnulf Paulsen, Stein Kaasa

3226 © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Methylprednisolone RCT for Cancer Pain, Fatigue, and Appetite Loss

Provision of study materials or patients: Ørnulf Paulsen, Jan Henrik Data analysis and interpretation: Ørnulf Paulsen, Pål Klepstad, Peter

Rosland, Nina Aass, Eva Albert Fayers, Stein Kaasa

Collection and assembly of data: Ørnulf Paulsen, Jan Henrik Rosland, Manuscript writing: All authors

Nina Aass, Eva Albert Final approval of manuscript: All authors

controlled, multicenter study—The Methylpred- 27. Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M: Karnof-

REFERENCES nisolone Preterminal Cancer Study Group. Eur J sky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung

Cancer Clin Oncol 25:1817-1821, 1989 cancer: A prospective, longitudinal study of 536

1. Klepstad P, Kaasa S, Cherny N, et al: Pain and 14. Ryan R, Booth S, Price S: Corticosteroid-use patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer

pain treatments in European palliative care units: A in primary and secondary brain tumour patients: A 32A:1135-1141, 1996

cross sectional survey from the European Associa- review. J Neurooncol 106:449-459, 2012 28. Twycross R, Wilcock A: Dextropropoxyphene:

tion for Palliative Care Research Network. Palliat 15. Tannock I, Gospodarowicz M, Meakin W, et Palliative Care Formulary. Nottingham, United King-

Med 19:477-484, 2005 al: Treatment of metastatic prostatic cancer with dom, Palliativedrugs.com, 2011, pp 337-340

2. Raphael J, Ahmedzai S, Hester J, et al: Cancer low-dose prednisone: Evaluation of pain and quality 29. Peuckmann V, Elsner F, Krumm N, et al:

pain: Part 1—Pathophysiology; oncological, pharma- of life as pragmatic indices of response. J Clin Oncol Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated

cological, and psychological treatments: A perspec- 7:590-597, 1989

with palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

tive from the British Pain Society endorsed by the 16. Lundström SH, Fürst CJ: The use of cortico-

11:CD006788, 2010

UK Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal steroids in Swedish palliative care. Acta Oncol 45:

30. Yennurajalingam S, Frisbee-Hume S, Palmer JL,

College of General Practitioners. Pain Med 11:742- 430-437, 2006

et al: Reduction of cancer-related fatigue with dexa-

764, 2010 17. Paulsen Ø, Aass N, Kaasa S, et al: Do cortico-

methasone: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-

3. World Health Organization: WHO’s cancer steroids provide analgesic effects in cancer pa-

pain ladder for adults. http://www.who.int/cancer/ tients? A systematic literature review. J Pain controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin

palliative/painladder/en/ Symptom Manage 46:96-105, 2013 Oncol 31:3076-3082, 2013

4. Knotkova H, Pappagallo M: Adjuvant analge- 18. Radbruch L, Strasser F, Elsner F, et al: Fatigue 31. Moertel CG, Schutt AJ, Reitemeier RJ, et al:

sics. Anesthesiol Clin 25:775-786, vi, 2007 in palliative care patients: An EAPC approach. Palliat Corticosteroid therapy of preterminal gastrointesti-

5. Fallon M, Hanks G, Cherny N: Principles of Med 22:13-32, 2008 nal cancer. Cancer 33:1607-1609, 1974

control of cancer pain. BMJ 332:1022-1024, 2006 19. Yavuzsen T, Davis MP, Walsh D, et al: Sys- 32. Popiela T, Lucchi R, Giongo F: Methylpred-

6. Swarm RA, Abernethy AP, Anghelescu DL, et tematic review of the treatment of cancer- nisolone as palliative therapy for female terminal

al: Adult cancer pain. J Natl Compr Canc Netw associated anorexia and weight loss. J Clin Oncol cancer patients: The Methylprednisolone Female

11:992-1022, 2013 23:8500-8511, 2005 Preterminal Cancer Study Group. Eur J Cancer Clin

7. Lussier D, Portenoy RK: Adjuvant analgesics 20. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, et al: Use of Oncol 25:1823-1829, 1989

in pain management, in Hanks G, Cherny NI, Christa- opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: 33. Willox JC, Corr J, Shaw J, et al: Prednisolone

kis NA, et al (eds): Oxford Textbook of Palliative Evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. as an appetite stimulant in patients with cancer. Br

Medicine (ed 4). New York, NY, Oxford University Lancet Oncol 13:e58-e68, 2012 Med J (Clin Res Ed) 288:27, 1984

Press, 2010, pp 706-734 21. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM: Pain assessment: 34. Bruera E, Moyano JR, Sala R, et al: Dexameth-

8. Zhang JM, An J: Cytokines, inflammation, and Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad asone in addition to metoclopramide for chronic

pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 45:27-37, 2007 Med Singapore 23:129-138, 1994 nausea in patients with advanced cancer: A random-

9. Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Milligan ED, et 22. Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al: The ized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 28:

al: “Listening” and “talking” to neurons: Implications Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): 381-388, 2004

of immune activation for pain control and increasing A simple method for the assessment of palliative 35. Stanbury RM, Graham EM: Systemic cortico-

the efficacy of opioids. Brain Res Rev 56:148-169, care patients. J Palliat Care 7:6-9, 1991

steroid therapy: Side effects and their management.

2007 23. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al:

Br J Ophthalmol 82:704-708, 1998

10. Mensah-Nyagan AG, Meyer L, Schaeffer V, et The European Organisation for Research and Treat-

36. Fardet L, Kassar A, Cabane J, et al:

al: Evidence for a key role of steroids in the modu- ment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instru-

Corticosteroid-induced adverse events in adults:

lation of pain. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34:S169- ment for use in international clinical trials in

Frequency, screening and prevention. Drug Saf 30:

S177, 2009 (suppl 1) oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365-376, 1993

861-881, 2007

11. Salerno A, Hermann R: Efficacy and safety of 24. Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al: EORTC

steroid use for postoperative pain relief: Update and QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. http://groups.eortc.be/ 37. Braun TP, Zhu X, Szumowski M, et al: Central

review of the medical literature. J Bone Joint Surg qol/manuals nervous system inflammation induces muscle atro-

Am 88:1361-1372, 2006 25. Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al: Inter- phy via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-

12. Bruera E, Roca E, Cedaro L, et al: Action of preting the significance of changes in health-related adrenal axis. J Exp Med 208:2449-2463, 2011

oral methylprednisolone in terminal cancer patients: quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16:139-144, 1998 38. Schakman O, Gilson H, Kalista S, et al: Mech-

A prospective randomized double-blind study. Can- 26. Kaasa S, Apolone G, Klepstad P, et al: Expert anisms of muscle atrophy induced by glucocorti-

cer Treat Rep 69:751-754, 1985 conference on cancer pain assessment and classifi- coids. Horm Res 72:36-41, 2009 (suppl 1)

13. Della Cuna GR, Pellegrini A, Piazzi M: Effect of cation: The need for international consensus— 39. Dietrich J, Rao K, Pastorino S, et al: Cortico-

methylprednisolone sodium succinate on quality of Working proposals on international standards. BMJ steroids in brain cancer patients: Benefits and pit-

life in preterminal cancer patients: A placebo- Support Palliat Care 1:281-287, 2011 falls. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 4:233-242, 2011

■ ■ ■

www.jco.org © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology 3227

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Paulsen et al

GLOSSARY TERMS

chemokines: cytokines that are responsible for chemotactic Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance sta-

responses. Chemokines are heparin-binding proteins, which play tus: criteria used by doctors and researchers to define the progression

a role in a variety of biologic processes, the most important being of a patient’s disease, assessing how the disease affects daily living habits,

leukocyte chemotaxis. Their classification as C, CC, CXC, and and to assist in the determination of the appropriate treatment and

CX3C is based on the position of cysteine residues that form two prognosis.

disulfide bonds. Typically, chemokines mediate their effects

through G protein– coupled seven-transmembrane domain re- Karnofsky performance score: a standard way of measuring the

ceptors, which belong to four families on the basis of their affin- ability of patients with cancer to perform ordinary tasks. Karnofsky per-

ity for a given chemokine–CXCR1 to CXCR5, CCR1 to CCR9, formance scores range from 0 to 100. A higher score means the patient

XCR1, and CX3CR1. is better able to carry out daily activities. The Karnofsky performance

score may be used to determine a patient’s prognosis, measure changes

in a patient’s ability to function, or decide whether a patient could be

included in a clinical trial.

cytokines: cell communication molecules that are secreted in stratification factor: a factor used to separate data into subgroups

response to external stimuli. to determine whether that factor is significant.

ASCO’s Cancer Genetics Program

ASCO University has developed a comprehensive eLearning program that is focused on hereditary cancer genetics. Take

this expert-led program to gain greater competence in recording and interpreting family history and to know when to refer

for counseling and testing. Members save 20% at asco.org/store.

3228 © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

Methylprednisolone RCT for Cancer Pain, Fatigue, and Appetite Loss

Acknowledgment

We thank Sebastian von Hofacker, Arve Nordbø, Frode Skanke, Erik Hellem, Katrin Rut Sigurdardottir, and Morten Thronæs (site

investigators who recruited patients and gathered data); Marianne Aamand and Ragnhild Thormodsrød (coordinating study nurses who

performed follow-up at study centers); Grethe Skorpen Iversen, Bente Elisabeth Marum, Bente Miriam Christiansen, Cinzia Marini, Torbjørn

Øvreness, and Ingunn Eriksen (study nurses); Karin Tulluan and Marianne Bjelkåsen (randomization); Gunnhild Jacobsen (assistance with

database design and SPSS statistical software); Lone Nielsen (pharmacist); and staff and patients for participation.

www.jco.org © 2014 by American Society of Clinical Oncology

Information downloaded from jco.ascopubs.org and provided by at Univ of Chicago Library on October 9, 2014 from

Copyright © 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

128.135.12.127

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Magic Frequencies: Excerpted From The Mixing Engineer's HandbookDocument5 pagesMagic Frequencies: Excerpted From The Mixing Engineer's HandbookmehmetkurtulusNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Moors Sovereign Dollarium 500 Gold Backed Dollarium PicautoDocument2 pagesMoors Sovereign Dollarium 500 Gold Backed Dollarium Picautoakil kemnebi easley elNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Permaculture - Plants Suitable For Ground Cover (P) - Plants For A FutureDocument2 pagesPermaculture - Plants Suitable For Ground Cover (P) - Plants For A Futurecontadino_impazzitoNo ratings yet

- Blood Physiology 2022Document116 pagesBlood Physiology 2022Gurmessa FekaduNo ratings yet

- A. A. Allen The Price of Gods Miracle Working PowerDocument52 pagesA. A. Allen The Price of Gods Miracle Working Powerprijiv86% (7)

- Training Sinal PDFDocument15 pagesTraining Sinal PDFlobitoferoz81No ratings yet

- Graha YuddhaDocument10 pagesGraha YuddhaHeather WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Mary Szybist On Visual Poetry Compressed PDFDocument5 pagesMary Szybist On Visual Poetry Compressed PDFcarlos.enrique.fonseca1440No ratings yet

- Lymphatic System PowerpointDocument20 pagesLymphatic System Powerpointabisantiago6131No ratings yet

- Consideration of Some Other Specific Indications: BacteremiaDocument18 pagesConsideration of Some Other Specific Indications: BacteremiaMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Management of Hypoparathyroidism: Summary Statement and GuidelinesDocument11 pagesManagement of Hypoparathyroidism: Summary Statement and GuidelinesMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Pengantar Reproduksi Menstruasi: Fisiologi DR - Susy OliviaDocument34 pagesPengantar Reproduksi Menstruasi: Fisiologi DR - Susy OliviaMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Pharmacology: Management of Acute Agitation in The Emergency DepartmentDocument13 pagesPharmacology: Management of Acute Agitation in The Emergency DepartmentMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Diagnosis: Systemic Inflamatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) : Assess Haematological & Metabolic StateDocument10 pagesDiagnosis: Systemic Inflamatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) : Assess Haematological & Metabolic StateMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Seizure Focal SeizuresDocument8 pagesSeizure Focal SeizuresMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Gangguan Akibat Kekurangan Iodium: Dr. Idawati Karjadidjaja Ms. SPGKDocument22 pagesGangguan Akibat Kekurangan Iodium: Dr. Idawati Karjadidjaja Ms. SPGKMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Tachycardia Ventricular: - 3 or More Consecutive Ectopic Ventricular ComplexesDocument2 pagesTachycardia Ventricular: - 3 or More Consecutive Ectopic Ventricular ComplexesMOHAMMAD JOFA RACHMAN PUTERANo ratings yet

- Concept Paper Group 1Document9 pagesConcept Paper Group 1Kaime KeilarNo ratings yet

- Catchment CharacterisationDocument48 pagesCatchment CharacterisationSherlock BaileyNo ratings yet

- EngineeringDocument107 pagesEngineeringSuezakumeNo ratings yet

- Cramers Rule 3 by 3 Notes PDFDocument4 pagesCramers Rule 3 by 3 Notes PDFIsabella LagboNo ratings yet

- 2005 Removing Aland RegeneratingDocument6 pages2005 Removing Aland RegeneratingHebron DawitNo ratings yet

- Ix T7AM-CAN - Beijer ElectronicsDocument1 pageIx T7AM-CAN - Beijer ElectronicsKen VikstromNo ratings yet

- The Laws of Motion ¿ ¿ Cengage LearningDocument57 pagesThe Laws of Motion ¿ ¿ Cengage LearningNguyễn Khắc HuyNo ratings yet

- QuizBowl QuestionsDocument84 pagesQuizBowl QuestionsJowel MercadoNo ratings yet

- Scientific Approaches For Impurity Profiling in New Pharmaceutical Substances and Its Products-An OverviewDocument18 pagesScientific Approaches For Impurity Profiling in New Pharmaceutical Substances and Its Products-An OverviewsrichainuluNo ratings yet

- CekocideDocument1 pageCekocideKaren Claire HorcaNo ratings yet

- WBMDocument90 pagesWBMMiguel RegisNo ratings yet

- Design and Fabrication of Single Cylinder Solenoid EngineDocument7 pagesDesign and Fabrication of Single Cylinder Solenoid EngineVIVA-TECH IJRINo ratings yet

- NUTRACEUTICALDocument8 pagesNUTRACEUTICALShubham GuptaNo ratings yet

- International StandardDocument8 pagesInternational Standardnazrul islamNo ratings yet

- Hemiplegia Case 18.12.21Document5 pagesHemiplegia Case 18.12.21Beedhan KandelNo ratings yet

- BCA 5005 Minor Project Synopsis Format & GuidelinesDocument7 pagesBCA 5005 Minor Project Synopsis Format & GuidelinesAnu VermaNo ratings yet

- Case Report - Anemia Ec Cervical Cancer Stages 2bDocument71 pagesCase Report - Anemia Ec Cervical Cancer Stages 2bAnna ListianaNo ratings yet

- 5754 Aluminum CircleDocument2 pages5754 Aluminum Circlewei huaNo ratings yet

- J-20 Stealth Fighter Design Balances Speed and Agility - Defense Content From Aviation WeekDocument9 pagesJ-20 Stealth Fighter Design Balances Speed and Agility - Defense Content From Aviation WeekMahesNo ratings yet

- A Novel Wastewater Derived BiodieselDocument13 pagesA Novel Wastewater Derived BiodieselYuri ClaroNo ratings yet

- Coord Angle and BearingDocument18 pagesCoord Angle and BearingvNo ratings yet