Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Faal Paru T.yusfan

Uploaded by

nina purnamasariCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal Faal Paru T.yusfan

Uploaded by

nina purnamasariCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Women’s Health Dovepress

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Evaluation of Pulmonary Function Tests Among

Pregnant Women of Different Trimesters in

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, Shoa, Ethiopia

This article was published in the following Dove Press journal:

International Journal of Women’s Health

1

Yosef Eshetie Amare Introduction: Pregnancy is characterized by a sequence of dynamic physiological changes

Diresibachew Haile 2 that impact multiple organ system functions and is associated with various changes in

1

pulmonary anatomy and physiology. Precise knowledge of the pulmonary function test

Department of Biomedical Sciences,

Institute of Medicine and Health Sciences, parameters helps to understand and manage the course and outcome of pregnancy leading

For personal use only.

Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, to safe delivery. It also helps to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary interventions. The aim

Ethiopia; 2Department of Physiology,

of this study was to evaluate the effect of normal pregnancy on pulmonary function tests

College of Medicine and Health Sciences,

Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, among pregnant women in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, Ethiopia.

Ethiopia Methods: A total of 176 study participants (first, second, and third trimester; and control)

were involved under a comparative cross-sectional study design and convenience sampling

technique. Anthropometric data, oxygen saturation of arterial blood, and pulmonary function

tests were measured. Data were tabulated and statistically analyzed using SPSS version 20.0

statistical software. Means of all parameters were compared using one-way ANOVA fol

lowed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison test. Statistical significance was preset at a

p-value of less than 0.05.

Results: Mean of FVC for the controls, first, second, and third trimesters was 2.59 ± 0.26,

2.13 ± 0.15, 1.93 ± 0.27, and 1.90 ± 0.11 liters, respectively. Except for FEV1%, the mean

values of FVC, FEV1, PEFR, and FEF 25–75% in the pregnant group (all the three trimesters)

were significantly decreased from the controls (P<0.05). Strong negative correlation was

seen between SaO2 and RR (r= −0.865; P <0.01). As the pregnancy progressed from first to

the third trimester, dynamic pulmonary function tests (FVC, FEV1, FEF25-75%, and PEFR)

were dropped and the respiratory rate increased.

Conclusion: The results had shown the tendency of obstructive pattern while pregnancy

becoming advanced. We have observed also a remarkable decline of SaO2 in pregnant

women that might be counterbalanced by raised respiratory rate.

Keywords: pregnancy, high altitude, FVC, trimester, oxygen saturation

Background

Pregnancy causes physiological and anatomical changes in different body systems.1–3

The physiological changes occurring in a pregnant woman are vast and widespread.

These include changes in genital organs, an increase in breast size, weight gain, and

other systemic alterations including respiratory, cardiovascular, body water metabo

Correspondence: Yosef Eshetie Amare lism, hematological, and metabolic changes.4 These adaptations are necessary to meet

Department of Biomedical Sciences,

Institute of Medicine and Health Sciences, the increased metabolic demands of the mother and the fetus.

Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia

Tel +251910966364

The combination of hormonal changes and mechanical effects of the enlarging

Email yophy2006@gmail.com uterus leads to a change in the pulmonary physiology of a mother.1,5 Progressively

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12 1135–1143 1135

DovePress © 2020 Amare and Haile. This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/

http://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S275742

terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). By accessing

the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed.

For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms (https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php).

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Amare and Haile Dovepress

enlarging uterus causes a diaphragm position to rise Ventilatory studies at high altitudes have shown decreased

approximately 4 cm above its usual resting position that forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1

favors the lung to hold less air.6 As a result, lung volumes second (FEV1), and maximal mid expiratory flow rate

are compromised including functional residual capacity (FEF25-75%).16,18

(FRC), total lung capacity (TLC), and vital capacity Over breathing is one of the many physiological adap

(VC).7,8 Dynamic pulmonary function tests like FVC, tations of pregnancy which is made considerably in the

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

FEV1, FEV1%, and FEF25-75% also decrease due to the progress of maternal and fetal possible needs. The increase

gravid state of advanced pregnancy.1,2 in minute ventilation that accompanies pregnancy is often

Besides the size of the gravid uterus, many of the perceived as shortness of breath. About 75% of pregnant

physiological changes in the respiratory system are women have exertional dyspnea by 30 weeks of gestation.

mediated by increased progesterone levels.9 Progesterone Shortness of breath at rest or with mild exertion is so

is a known stimulant of breathing, and its level in the common that it is often referred to as physiologic dyspnea

blood gradually rises approximately from 25 ng/mL at and is completely reversible once pregnancy is over.4,15

six weeks of gestation to 150 ng/mL at term.10,11 This Understanding of the changes is critical in distinguishing

progressive increment is responsible for the raised respira the common dyspnea that occurs during normal pregnancy

tory depth and rate.12,13 Progesterone increases tidal from pathophysiologic states associated with cardiopul

volume by 200mL (from 500mL to 700mL) and minute- monary diseases seen in pregnancy and anticipating dis

ventilation approximately by 40%. This is by increasing ease worsening conditions during pregnancy in those

For personal use only.

the sensitivity of the respiratory center to carbon dioxide. women with cardiopulmonary diseases.1

Progesterone-mediated hypersensitivity to CO2 increases Therefore, accurate knowledge of the physiological

the respiratory rate by 10% which attributes to the raised changes in pulmonary functions during normal pregnancy

oxygen consumption during pregnancy.13 It also causes a is necessary. In Ethiopia, there are few published findings

fall in the functional residual capacity that comprises resi on pulmonary function tests among pregnant women at

dual and expiratory reserve volume. As a consequence, altitude. Knowledge of predicted changes in the respira

alveolar ventilation increases.3 Total lung capacity is mini tory system associated with pregnancy helps clinicians to

mally decreased because of the reduction in residual prevent misdiagnosis of physiological changes as patholo

volume.13 Moreover, pregnancy-induced elevated proges gical. Thus, the present study focused on the evaluation of

terone causes bronchial and tracheal smooth muscle pulmonary function tests among pregnant women of the

relaxation. Therefore, the upward displacement of the dia different trimesters in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital,

phragm along with reduced strength of expiratory muscles Shoa, Ethiopia.

may hamper forceful expiration.5 Progesterone increases

respiratory rate and tidal volume which in turn drives an

Materials and Methods

increment of both alveolar and minute ventilation and

hence a fall in PaCO2.7,9,14 PaCO2 might reach to a

Study Area

This study was carried out at Debre Berhan Referral

mean of 20–30 mmHg in the last 12 weeks of pregnancy,6

Hospital. Debre Berhan is located in the North Shoa

resulting in constriction of bronchial smooth muscle.5

Zone of the Amhara Region, about 130 kilometers North

Even, progesterone accompanies reduced chest wall com

East of Addis Ababa at an average altitude of 2840 meters

pliance through structural changes in the ribcage and

above sea level.

abdominal compartments.15

At high altitude, PaO2 in the atmosphere falls thereby

the number of molecules of O2 present per breath Study Design and Period

decreases that leads to hypobaric hypoxia and this would The comparative cross-sectional study design was

be more pronounced during pregnancy.16,17 Moreover, employed to assess the effect of normal pregnancy on

ventilation has a positive correlation with the consumed pulmonary function outcomes among pregnant women

energy cost and also, the power and endurance of respira who visited the ANC clinic of Debre Berhan Referral

tory muscles which have basic roles for ventilation Hospital from January to March 2019. Non-pregnant

activity.16 This has been shown by the fatigue of diaphrag women who came for family planning services were

matic muscle that may affect breathing at high altitude. taken as controls. One hundred and seventy-six study

1136 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Amare and Haile

participants were recruited and divided equally into four Sample Size Determination

groups, each comprising 44 women. The groups include The sample size was determined by considering the fol

those in their first, second, and third trimesters, and also lowing assumptions: α (two-sided) = 0.05; power = 0.80;

the non-pregnant women as controls. effect size = 2.6; SD = 8.7, and the total sample size was

becoming 176 mothers. These 176 mothers were purposely

Source Population allocated into four groups each containing 44 mothers

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

All pregnant and non-pregnant women in Debre Berhan (first trimester, second trimester, third trimester, and

town, North Shoa Zone, Amara region, Ethiopia. controls).

Study Population Sampling Procedure and Technique

All pregnant women who visited the ANC clinic, and non-

All the women who visit the ANC and family planning

pregnant women who visited the family planning clinic of

clinic of Debre Berhan referral Hospital were considered.

Debre Berhan referral Hospital.

Those pregnant and non-pregnant women that fulfilling

inclusion criteria were included through convince

Inclusion Criteria sampling.

Healthy pregnant women who were volunteered to parti

cipate in the study. And, those clients came to use either of

any family planning method. Data Collection Tools and Process

For personal use only.

Height and weight measuring scale, Spiropro handheld

Exclusion Criteria spirometer with extra pneumotachometer with mouthpiece

Those participants who had a history of (smoking, general (Jaeger, digital Spiropro, 150×9×40 mm, 0.2kg, recharge

debility, recurrent or persistent expectoration, asthma or able, and touch sensitive display), and pulse oximetry

recurrent bronchitis, occupational exposure to lung toxins, (Oxi-Max N-65) were used. The height was taken in

having diabetes mellitus, any current or past cardiovascu centimeters (nearest to 0.1 cm) without shoes, feet

lar or respiratory disorder) and with the sign of any bone together, standing as tall as possible with the eye level

deformity of the thoracic cage were excluded from the and looking straight ahead, and using an accurate measur

study. ing device. Weight was also measured in kilograms (near

est to 0.1 kg) of the subject wearing light clothing and

barefooted on the weighing scale. The PFTs were mea

Operational Definition

First Trimester sured with a spirometer under recommendations of the

Designates gestational age from 1–12 weeks; Second American Thoracic Society (ATS) at room temperature

Trimester: Designates gestational age from 13–26 weeks; by the same investigator to ensure its validity. Before

Third Trimester: Designates gestational age from 27–40+ each measurement, the spirometer was calibrated by a

weeks; Control: Non-pregnant women they came for uti volume of 1 liter syringe. Following receipt of consent,

lization of family planning service. the study participants rested for 15 minutes before mea

surements and the investigator informed study participants

High Altitude about the whole procedure and allowed to do multiple

It is an elevation of between 1500m to 3500m above sea trials before the start of the experiment to familiarize the

level.19 subjects with the test procedures. The study participants

FVC: The volume of air that can forcibly be blown out were asked to sit comfortably in a chair. After appropriate

after maximum inspiration; FEV1: This is the speed of air placement of the nose clip, they were instructed to seal the

forcibly expelled from the lungs in the first one second lips around the sterile mouthpiece. The study participant

from maximal inspiration; FEV1%: The percentage of the was asked to breathe in maximally and then forcefully

FVC expired in the first one second of maximal forced expire the air, as fast and as far as possible. Each partici

expiration following full inspiration; FEF25-75%: Indicates pant performed the test at least three times, as per the

expiratory flow in the middle portion of the FVC; PEFR: requirement of ATS so that at least two of the maneuvers

The highest flow achieved from maximal lung inflation were reproducible. In some cases, the tests were made

and forced expiration.20 more than three times, when the participant failed to

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12 1137

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Amare and Haile Dovepress

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

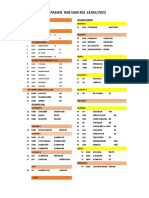

Figure 1 Mean age of study participants in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, January to March 2019.

produce reliable value. Maternal SaO2 is also measured in and it was conducted in accordance with the declaration of

the sitting position at the dominant index finger. Helsinki.32

Respiratory rate was recorded by inspection and palpation

on the chest and abdomen. Result

For personal use only.

Characteristics of Study Participants

Data Quality Control A total of 176 study participants were involved in this

To assure the quality of the data, the following measures study. Out of these, 132 were pregnant women correspond

were undertaken. Training has been given to data collec ingly allocated to each trimester and the rest were 44

tors about the objective of the study, data collection pro controls. Anthropometric measurements, respiratory rate,

cedures, and relevance of the study before actual data oxygen saturation of arterial blood, and dynamic pulmon

collection. The principal investigator was actively ary function tests were measured for all 176 individuals.

involved in supervising data collection and checking the The mean age of first, second, third trimesters; and

control were (24.41 ± 2.34, 25.02 ± 2.31, 25.07 ± 3.17,

completeness of the sheet daily. The collected data were

and 24.36 ± 1.57 years) respectively (Figure 1). An insig

reviewed before entry. The spirometer was regularly

nificant difference of age was seen in all groups.

checked for ambient conditions (temperature of 17–20°C,

When comparing the anthropometric measurements of

65–74% humidity, and a barometric pressure of 1018–

each group; the height of third-trimester women was sig

1025 hPa).

nificantly (P < 0.01) higher than the control group. The

weight of all trimesters increased significantly (P < 0.01)

Data Processing and Analysis when compared to the control group. The BMI of the first-

Data were coded, entered, and cleaned after checking for trimester group did not show significant variation when

completeness and consistencies. SPSS version 20.0 statis compared to the control group. But, it was increased sub

tical software package was used for analysis. Mean ± SD stantially in the second and third trimesters (P < 0.01).

of all study groups were compared for statistical signifi BMI across all study groups lied within a normal range.

cance by independent “t” test and one-way ANOVA.

Statistical significance was preset at P< 0.05. Assessing Arterial Blood Oxygen

Saturation and Respiratory Rate of Study

Ethical Considerations Participants

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review The mean respiratory rate was significantly increased in all

Committee of the Department of Physiology, Addis Ababa trimesters as compared to the control group. Likewise, arter

University. Full information was given to participants on ial blood oxygen saturation of pregnant women was signifi

the purpose and significance of the study. The informed cantly decreased when compared to the control group (Table

and written consent was then obtained from all participants 2). The respiratory rate of pregnant women was showing

1138 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Amare and Haile

increasing pattern as gestational age rises. However, arterial Discussion

blood oxygen saturation was significantly dropping as gesta In this study, the mean difference in age and height of

tional age upsurges. The arterial blood oxygen saturation and pregnant women were statistically insignificant as com

respiratory rate of study participants have revealed a strong pared to the control group. This is in agreement with

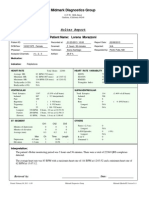

negative correlation (p<0.01, r = - 0.865) (Figure 2). previous finding.1,5,7,21,22 Hence, possible variation in

indices of PFTs due to age and height would not be a

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

factor for this study. The difference in mean weight and

Assessing Dynamic Pulmonary Function

BMI was statistically significant amongst pregnant and

Testes control groups. The present study showed that both weight

As presented in Table 3, the parameters of PFTs were com

and BMI were increased significantly per the rising of

pared across each group. Comparing first trimester and sec

gestational age (Table 1). Other studies revealed the

ond-trimester pregnant women, the mean of FEV1%, FEF25- same result.1 This might be because of the normal weight

75%, and PEFR did not show a significant difference. gain, and uterine enlargement which occurs in pregnancy.

Meanwhile, the mean FVC (P <0.05) and FEV1 (P < 0.01) Our study showed that the mean RR was significantly

of first trimester women have shown significant increment increased from the first trimester to the third trimester

when compared to second-trimester women. Except for which is in agreement with several studies.11,21,23

unchanged FEV1% mean value, other PFTs parameters were Likewise, the mean RR of the control group was markedly

significantly (P < 0.01) decreased in third-trimester women decreased when compared to all the three trimesters (Table

For personal use only.

when compared to first trimester women. Mean values of 1). Other studies also reported a 10%,9 and borderline

PFTs parameters of the control group were significantly (P < increment of RR during pregnancy.4 This might be due

0.01) increased when compared to all the groups of pregnant to the increasing pattern of progesterone; from 25 ng/mL

women; except, FEV1% remained insignificant. at 6 weeks of gestation to 150 ng/mL at term thereby

Figure 2 Correlation between mean arterial blood oxygen saturation and respiratory rate of study participants in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, January to March 2019.

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12 1139

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Amare and Haile Dovepress

Table 1 Comparison of Anthropometric Measurements of Study This study found a strong negative correlation between

Participants in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, January to March RR and SaO2 (P< 0.01; r = - 0.865). This can be due to the

2019

considerable reduction in the partial pressure of oxygen in

Gestational Height (m) Weight (kg) BMI (kg/m2) Debre Berhan as compared to sea level which can trigger a

Age compensatory rise in respiratory rate.

T1 1.57 ± 0.01 58.57 ± 3.81 a*

19.77 ± 1.02 In the present study, the mean arterial blood oxygen

a* a*

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

T2 1.58 ± 0.02 60.80 ± 3.82 20.87 ± 1.08 saturation was significantly dropped as gestational age

a* a* a*

T3 1.59 ± 0.03 66.02 ± 3.87 21.69 ± 1.22 increased while the mean SaO2 of the control group

Control 1.58 ± 0.02 55.43 ± 4.27 20.03 ± 1.08

became higher (Table 2). Previous studies have shown

Notes: Values are expressed as mean ± SD; n=44; aCompared to control; *P< 0.01.

similar findings.25 However, increased SaO2 with

Abbreviations: T1, first trimester; T2, second trimester; T3, third trimester; BMI,

body mass index. advanced gestation,23 and unchanged mean SaO2

(~97%),7,26 were reported. The reduced SaO2 for Debre

Table 2 Mean of Arterial Blood Oxygen Saturation and Berhan pregnant women might be due to diminished par

Respiratory Rate of Study Participants in Debre Berhan tial pressure of oxygen which reduces alveolar oxygen

Referral Hospital, January to March 2019 tension. Other possible reasons could also due to the

Gestational Age RR (Breath/Minute) SaO2 (%) increment of maternal plasma volume by 45%, and red

a* a* blood cell mass by 20–30% during pregnancy. In the

T1 17.77 ± 1.93 95.50 ± 1.50

T2 19.80 ± 1.29 a*

94.23 ± 1.13 a* meantime, this disproportionate increment of plasma

For personal use only.

T3 21.50 ± 1.44 a**

91.23 ± 1.14 a** volume with red blood cell mass might cause arterial

Control 13.66 ± 1.08 97.14 ± 1.81 oxygen to be dissolved more and then unable to be

Notes: Values are expressed as mean ± SD; n=44; aCompared to control; *P<0.05, detected by pulse oximetry easily.27

**

P< 0.01.

Abbreviations: T1, first trimester; T2, second trimester; T3, third trimester; RR,

The Mean FEV1 of all the three trimesters was found to

respiratory rate; SaO2, oxygen saturation of arterial blood. be significantly decreased as compared to the control

group. Previous studies support our findings.1,2,5,7,11 In

other studies, however, FEV1 was significantly reduced

triggering the primary respiratory center by increasing the only in the third trimester while it was showing an insig

sensitivity of the respiratory center to carbon dioxide.10,11 nificant difference between the first and second trimester

Furthermore, gestational hyperventilation is attributed to when compared to the control group.28

upward displacement of the diaphragm, hypervolemia, Our study found an insignificant difference in mean

increased cardiac output, and increased demand a growing FEV1% between pregnant and non-pregnant control

fetus.21 However, another study reported no change in groups which is consistent with other similar studies.29

respiratory rate during pregnancy.24 This is probably, Unlike our results, a substantial decline of FEV1% was

because, sometimes increase in ventilation occurs without reported by numerous studies.2,11,28 Other findings also

an increase in respiratory rate; and accomplished mainly stated that raised FEV1% in all trimesters as compared to

by a rise in tidal volume only. non-pregnant counterparts.7 The mean FEV1% of second

Table 3 Comparison of Mean PFTs Across Pregnant Women of Each Trimester and Control in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital,

January to March 2019

Parameters T1 T2 T3 Control

a** a** b* a** b**

FVC(L) 2.13 ± 0.15 1.93 ± 0.27 1.90 ± 0.11 2.59 ± 0.26

a** a** b** a** b** c*

FEV1 (L) 1.87 ± 0.08 1.73 ± 0.22 1.60 ± 0.07 2.29 ± 0.22

FEV1% (%) 86.50 ± 4.10 86.11 ± 3.99 86.73 ± 3.49 86.73 ± 3.70

a** a** a** b** c*

FEF25-75% (L/s) 1.80 ± 0.06 1.74 ± 0.22 1.59 ± 0.12 2.07 ± 0.11

a** a** a** b** c*

PEFR (L/s) 4.30 ± 0.58 4.43 ± 0.52 3.78 ± 0.34 4.75 ± 0.38

a b c **

Notes: Values are expressed as mean ± SD; n=44; Compared to control; Compared to T1; Compared to T2; *P<0.05, P< 0.01.

Abbreviations: T1, first trimester; T2, second trimester; T3, third trimester.

1140 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Amare and Haile

and third-trimester pregnant women was slightly attributable to hormonal changes.11 However, in this

decreased as compared to non-pregnant women.1 The study, PEFR was highly dropped in the third trimester.

present study revealed that mean FVC in the third trime This is probably because the PEFR maneuver involves a

ster significantly reduced when compared to the control muscular element that is negatively affected due to the

group; which was in agreement with others.5,7,22 The downward displacement of the diaphragm around full-

decrease in FVC is attributable to the mechanical pressure term pregnancy.31

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

of enlarging gravid uterus, elevating the diaphragm, and

restricting the movements of lungs that hamper the force

Conclusion

ful expiration. The current study implied a significant

During pregnancy, the mean of respiratory parameters

decrease in mean FEF25-75% in all the trimesters of preg

declines as gestational age progresses from first to the

nancy as compared to the control group, and a similar

third trimester. Moreover, mean PFTs of each trimester

result was reported.2 The reductions in FEF25-75% might

of pregnancy significantly reduced when compared to

be due to reduced lung volumes as the pregnancy is get

non-pregnant controls. Except for FEV1% other pulmon

ting advanced.9

ary function tests including FVC, FEV1, PEFR, and

In our study, the mean FVC, FEV1, and FEF25%-75% of

FEF25-75% decreased significantly. Thus the present study

the third-trimester pregnant women significantly decreased

concluded PFTs of pregnant women would show a ten

as compared to the control group. This finding was compar

dency of restrictive pattern. These outcomes might arise

able with other studies.1,21,22 The present study revealed that

For personal use only.

from a combination of hormonal changes and mechanical

persistent mean FEV1% throughout pregnancy. This might

adjustments of the enlarging uterus that has a significant

be due to a proportional decrement of FEV1 and FVC

effect on the pulmonary physiology of the pregnant

thereby the ratio of FEV1/FVC has appeared like unity. In

mother. It was also concluded that the raised respiratory

contrast, the sustained mean values of FVC, FEV1, and

rate would happen when gestational age increased. On the

FEV1% were presented from first to the third trimester.7

other hand, oxygen saturation of arterial blood declined as

However, another study described a definite increase of

pregnancy advances. These alterations are compulsory to

FEV1% due to less drop in FEV1 as compared to FVC.22

meet the increased metabolic demands of the mother and

In line with ours, studies reported a significant fall in

fetus. Therefore, the present study concluded that preg

FEV1 of the third trimester as compared to the first

nancy at altitude can bring about compensatory changes to

trimester.5,28 However, other studies found a highly sig

balance with the changes occurring in dynamic pulmonary

nificant decrease in FEV1 and FEF25-75% in the first trime

function tests. However, longitudinal studies may reveal

ster than the third trimester.2,11

better results with larger sample sizes; therefore, future

We found that significantly lower mean PEFR values

studies need to be done with large sample size and long

in pregnant women as compared to the non-pregnant

itudinal studies taking parity, chest size, type of preg

control which is in agreement with several studies.1,5,7,11

nancy, and other socioeconomic factors into

Other findings, however, accounted for no substantial

consideration.

change in PEFR in the first and second trimester except

that a significant decrease in the third trimester.4 Other

complementary studies found a significant decrease in Abbreviations

PEFR only in the third trimester.21,22 Our findings showed AAU, Addis Ababa University; ANC, Antenatal Care;

an extensive drop in PEFR for each trimester as compared ANOVA, Analysis of Variance; ATS, American Thoracic

to the control group. The decrease in mean PEFR may be Society; BMI, Body Mass Index; CI, Confidence Interval;

attributed to the lesser force of contraction of main expira cm, Centimeter; CO2, Carbon Dioxide; COPD, Chronic

tory muscles or could be due to the mechanical effect of Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; FEF25-75%, Forced

enlarging gravid uterus affecting the vertical dimension Expiratory Flow Rate at the Middle Part of FVC; FEV1,

by restricting the diaphragmatic movement. In line with Forced Expiratory Volume in one Second; FEV1%, FEV1 to

the current study, several researchers reported a progres FVC ratio x 100; FVC, Forced Vital Capacity; L/s, Liter per

sive decline in PEFR as gestation advanced from the first Second; PaCO2, Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide; PaO2,

to third trimester.4,5,7,30 A maximum decrease of PEFR Partial Pressure of Oxygen; PEFR, Peak Expiratory Flow

was documented in the first trimester which may be Rate; PFTs, Pulmonary Function Tests; RR, Respiratory

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12 1141

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Amare and Haile Dovepress

Rate; SaO2, Oxygen Saturation of Arterial Blood; SD, 7. Richlin S, Cusick W, Sullivan C, et al. Normative oxygen saturation

values for pregnant women at sea level. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns.

Standard Deviation. 1998;5(4):154–155. doi:10.1016/S1068-607X(98)00042-0

8. Pandey D, Garg D, Tripathi B, et al. Case report: dyspnea in preg

Data Sharing Statement nancy: an unusual cause. J Basic Clin Reproductive Sci. 2014;3

(1):68–70. doi:10.4103/2278-960X.129290

All used raw data are available and can be accessed when 9. Heidemann BH, McClure JH. Changes in maternal physiology during

reasonably requested. pregnancy. BJA CEPD Rev. 2003;3(3):65–68. doi:10.1093/bjacepd/

mkg065

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

10. LoMauro A, Aliverti A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy: phy

Ethical Approval siology masterclass. Breathe. 2015;11(4):297–301. doi:10.1183/

The proposal was approved by the Ethical Review 20734735.008615

11. Teli A, Dharwadkar A, Aithala M. A study of pulmonary functions of

Committee of the Department of Physiology, Addis women at different trimesters of pregnancy in Bldeu’s Shri Bm Patil

Ababa University before the beginning of the study. Medical College Hospital. Analytica Medica. 2010;13:28.

12. Cebakulu S. From Dyspnoea to Respiratory Failure in Pregnancy. In

Obstetrics and Gynaecology Forum. House Publications; 2014.

Acknowledgment 13. Yeomans ER, Gilstrap LC. Physiologic changes in pregnancy and

The authors express thanks to all participants who will their impact on critical care. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10):S256–S258.

doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000183540.69405.90

ingly helped us. We would also like to thank the College 14. Bhatia P, Bhatia K. Pregnancy and the lungs. Postgrad Med J.

of Medicine and Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University 2000;76(901):683–689. doi:10.1136/pmj.76.901.683

15. Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Respiratory physiology in pregnancy. Clin

for financial support.

Chest Med. 2011;32(1):1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2010.11.001

16. Chawla S, Saxena S. Physiology of high-altitude acclimatization.

For personal use only.

Author Contributions Resonance. 2014;19(6):538–548. doi:10.1007/s12045-014-00

57-3

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and 17. San T, Polat S, Cingi C, et al. Effects of high altitude on sleep and

design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of respiratory system and theirs adaptations. Scientific World J.

2013;2013. doi:10.1155/2013/241569

data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for

18. Zada W, Aydin, Framushi. Comparison of pulmonary function para

important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current meters changes at different altitudes in female athletes. Available

journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; from: https://repository.uma.ac.ir/id/eprint/7943. 2009.

19. Taylor AT. High-altitude illnesses: physiology, risk factors, preven

and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. tion, and treatment. Rambam Maimonides Med j. 2011;2:1.

doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10022

20. West JB. Respiratory Physiology: The Essentials. Lippincott

Funding Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

This study was sponsored by Addis Ababa University, 21. Panchal V, Dodiya D. Comparative study of dynamic lung function

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. tests between third trimester of pregnancy and non-pregnant women.

Int J Res Med. 2014;3(2):158–169.

22. Kaur V. Effect of advanced uncomplicated pregnancy on pulmonary

Disclosure function parameters of North Indian subjects. Indian J Physiol

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work, Pharmacol. 2010;54(1):69–72.

23. Haile D, Abebe Y. Trends of lung function indices, arterial blood

the authorship, and publication of this article. oxygen saturation and pulse rate among the first and third trimester

pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian JReproductive

Health. 2016;8:1.

References 24. Shailaja D, Srikanth D. Lung function tests in different trimesters of

1. Biswas D, Kulsange S. Effect of normal pregnancy on pulmonary pregnancy. Indian J Basic Appl Med Res. 2013;3(1):285–292.

function tests in a rural setting. Int J Physiol. 2013;1(2):27–32. 25. Yanamandra N, Chandraharan E. Anatomical and physiological

doi:10.5958/j.2320-608X.1.2.006 changes in pregnancy and their implications. Obstetric Intrapartum

2. Teli A, Doddamani P, Ghatnatti R, et al. Physiological alternation in Emergencies. 2012;1.

small airway parameters during pregnancy: its application in clinical 26. Van Hook J, Harvey CJ, Anderson GD. Effect of pregnancy on

scenario. Int J Biomed Res. 2013;4(4):173–178. doi:10.7439/ijbr. maternal oxygen saturation values: use of reflectance pulse oximetry

v4i4.239 during pregnancy. South Med J. 1996;89(12):1188–1192.

3. Carlin A, Alfirevic Z. Physiological changes of pregnancy and mon doi:10.1097/00007611-199612000-00011

itoring. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(5):801–823. 27. Branch DW, Wong LF. Normal Pregnancy, Pregnancy

doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.06.005 Complications, and Obstetric Management, in Contraception and

4. Omorogiuwa A, Iyawe V. Effect of parity on FVC and FEV1 during Pregnancy in Patients with Rheumatic Disease. Springer; 2014:31–

pregnancy. J Adv Med Med Res. 2015;1–9. 62.

5. Jadhav S, et al. Comparative study of pulmonary function tests on 28. Sunyal DK, et al. Study of forced expiratory volume in first second

different trimesters of pregnancy. Int J Current Res Rev. 2013;5 (FEV1) and ratio of forced expiratory volume in first second and

(2):118. forced vital capacity in percentage (FEV1/FVC%) in pregnant

6. Ratigan T. Anatomic and physiologic changes of pregnancy: anesthetic women. J Enam Med College. 2012;2(1):29–32. doi:10.3329/jemc.

considerations. AANA J. 1983;51(1):38–42. v2i1.11926

1142 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Amare and Haile

29. Phatak MS, Kurhade G. Short communication a longitudinal study of 31. Pradhan G, et al. Evaluation and comparison of lung function para

antenatal changes in lung function tests and importance of postpar meters during pregnancy. Int J Current Res Rev. 2014;6(7):35.

tum exercises in their recovery. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47 32. World Medical Association. World Medical Association declaration

(3):352–356. of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human

30. Bansal M, et al. Longitudinal study of peak expiratory flow rate in subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(4):373–374. World

pregnant women. NJIRM. 2012;3(1):34–38. Health Organization.

International Journal of Women's Health downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 182.3.4.247 on 02-Nov-2021

For personal use only.

International Journal of Women’s Health Dovepress

Publish your work in this journal

The International Journal of Women’s Health is an international, peer- manuscript management system is completely online and includes a

reviewed open-access journal publishing original research, reports, very quick and fair peer-review system, which is all easy to use.

editorials, reviews and commentaries on all aspects of women’s Visit http://www.dovepress.com/testimonials.php to read real quotes

healthcare including gynecology, obstetrics, and breast cancer. The from published authors.

Submit your manuscript here: https://www.dovepress.com/international-journal-of-womens-health-journal

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Women’s Health 2020:12 1143

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- 1 s2.0 S2666084921008056 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S2666084921008056 Mainnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- MR Tn. D EditDocument18 pagesMR Tn. D Editnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Mapping DR Irma 10-12-2022Document1 pageMapping DR Irma 10-12-2022nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Mapping Dr. Nurrahmah 10-12Document2 pagesMapping Dr. Nurrahmah 10-12nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Case of DeathDocument37 pagesCase of Deathnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Shafa 17 MeiDocument1 pageShafa 17 Meinina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- MARWAH Mikhwan-1Document1 pageMARWAH Mikhwan-1nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Mapping DR Herry P 10-12-2022Document1 pageMapping DR Herry P 10-12-2022nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- List RSB DAN RSL 14 MEI FUDocument1 pageList RSB DAN RSL 14 MEI FUnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Mapping Dr. Shilvanna SP.P 10-12-2022Document1 pageMapping Dr. Shilvanna SP.P 10-12-2022nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- JEJARING DR - Rahma, DR - Dewi, DR - Herry 10-10-2021Document1 pageJEJARING DR - Rahma, DR - Dewi, DR - Herry 10-10-2021nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Serum PCT and CRP Levels in Patients Infected by Different Pathogenic MicroorganismsDocument8 pagesComparison of Serum PCT and CRP Levels in Patients Infected by Different Pathogenic Microorganismsnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Ateletaksis Case ReportDocument17 pagesAteletaksis Case Reportnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Ape CopdDocument6 pagesApe Copdnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- WHO 2019 NCoV Therapeutics 2021.3 EngDocument71 pagesWHO 2019 NCoV Therapeutics 2021.3 Engnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Sars-Cov-2 Positivity Rates Associated With Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D LevelsDocument10 pagesSars-Cov-2 Positivity Rates Associated With Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levelsnina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Shafa 10.10.2021Document5 pagesShafa 10.10.2021nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Mapping Marwah 081021Document2 pagesMapping Marwah 081021nina purnamasariNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Nasogastric Gastrostomy Tube Feedling Guidelines v1.4Document45 pagesNasogastric Gastrostomy Tube Feedling Guidelines v1.4bandarascbNo ratings yet

- Physicswallah Mediclaim BenefitDocument17 pagesPhysicswallah Mediclaim BenefitᎷᏒ ᏗᏕᏂᎥᏕᏂ ᎶᏬᎮᏖᏗNo ratings yet

- WBC Usmle QuestionsDocument17 pagesWBC Usmle Questionssplinter594100% (1)

- Explore Style, Books, and More!: InterpersonalDocument1 pageExplore Style, Books, and More!: InterpersonalMuhammad YusufNo ratings yet

- Purpura Fulminans: Mechanism and Management of Dysregulated HemostasisDocument21 pagesPurpura Fulminans: Mechanism and Management of Dysregulated HemostasisntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Apa - Tehnologii MedicaleDocument125 pagesApa - Tehnologii MedicaleNick OviciNo ratings yet

- Application For The Post of Assistant Professor in DentistryDocument5 pagesApplication For The Post of Assistant Professor in DentistryVenkata Ramana Murthy VasupilliNo ratings yet

- Infection Control in ORDocument10 pagesInfection Control in ORaaminah tariqNo ratings yet

- Prometric SoalDocument42 pagesPrometric SoalSandra IrhamNo ratings yet

- What Is Moxibustion Acupuncturedrcmt PDFDocument3 pagesWhat Is Moxibustion Acupuncturedrcmt PDFStillingKruse2No ratings yet

- Full Report Holter Lorena M 1-23-13Document36 pagesFull Report Holter Lorena M 1-23-13traja_vlrNo ratings yet

- Theragran (Multiple Vitamins)Document3 pagesTheragran (Multiple Vitamins)ENo ratings yet

- Addiction CaseDocument8 pagesAddiction CasePooja varmaNo ratings yet

- Compulsive Sexual Behavior PDFDocument2 pagesCompulsive Sexual Behavior PDFmaya sofianaNo ratings yet

- Uworld Charts PDFDocument162 pagesUworld Charts PDFMaryam Fadah100% (3)

- First AidDocument71 pagesFirst AidprakashNo ratings yet

- Değişim Sınavı 2020Document29 pagesDeğişim Sınavı 2020Mustafa CinNo ratings yet

- Roru Exoendo - PancreasDocument13 pagesRoru Exoendo - PancreasRitz CelsoNo ratings yet

- Hospital Review 2017Document32 pagesHospital Review 2017NM Atif100% (5)

- Essential - Health - Packages - Docx Filename - UTF-8''essential Health PackagesDocument10 pagesEssential - Health - Packages - Docx Filename - UTF-8''essential Health PackagesYvonne Carmel Aguilar SunigaNo ratings yet

- ECMO, Adults BJA 2011Document5 pagesECMO, Adults BJA 2011RAGHAVENDRA VAGYANNAVARNo ratings yet

- Therapy ModuleDocument39 pagesTherapy ModuleSuruchi Jagdish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Akeem Cohall 11L Cancer in The CaribbeanDocument3 pagesAkeem Cohall 11L Cancer in The CaribbeanswashniggaNo ratings yet

- Generic Name: Frequent (10%) Baseline Assessment Antiemetic (Assess Intervention/EvaluationDocument11 pagesGeneric Name: Frequent (10%) Baseline Assessment Antiemetic (Assess Intervention/EvaluationIrene Soriano BayubayNo ratings yet

- IFU NormaCont3+ EDocument1 pageIFU NormaCont3+ Ethuy dinhNo ratings yet

- 3-Month UFABB With FA 2019sdsdDocument76 pages3-Month UFABB With FA 2019sdsdขายหนังสือเตรียมสอบ เข้ามหาลัย ราคาถูกNo ratings yet

- BrochureDocument2 pagesBrochureJFK100% (2)

- Clinical Services Plan TTM SamoaDocument69 pagesClinical Services Plan TTM SamoajohnkornieNo ratings yet

- Wan Et Al 2019 PDFDocument8 pagesWan Et Al 2019 PDFEdgar Huerta CardenasNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Blue Light Inactivation of Pathogenic Microbes - State of The ArtDocument44 pagesAntimicrobial Blue Light Inactivation of Pathogenic Microbes - State of The ArtJohn KibuukaNo ratings yet