Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gender and The Metaphorics Lori Chamberlain

Uploaded by

Işıl KeşkülOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gender and The Metaphorics Lori Chamberlain

Uploaded by

Işıl KeşkülCopyright:

Available Formats

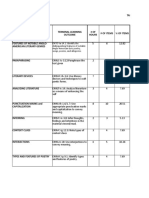

Gender and the Metaphorics of Translation

Author(s): Lori Chamberlain

Source: Signs, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Spring, 1988), pp. 454-472

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174168 .

Accessed: 10/06/2014 00:54

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

GENDER AND THE METAPHORICS

OF TRANSLATION

LORI CHAMBERLAIN

In a letterto the nineteenth-century violinistJoseph Joachim,Clara

Schumann declares, "Bin ich auch nicht producierend, so doch

reproducierend" (Even if I am not a creative artist,still I am re-

creating).' While she played an enormously importantrole repro-

ducing her husband's works, both in concert and later in preparing

editions of his work, she was also a composer in her own right;yet

until recently,historians have focused on only one composer in this

family.Indeed, as feminist scholarship has amply demonstrated,

conventional representations of women-whether artistic, social,

economic, or political-have been guided by a culturalambivalence

about the possibility of a woman artistand about the status of wom-

an's "work." In the case of Clara Schumann, it is ironic that one of

I want to acknowledge and thank the many friendswhose conversations with

me have helped me clarifymythinkingon the subject ofthisessay: Nancy Armstrong,

Michael Davidson, Page duBois, Julie Hemker, Stephanie Jed, Susan Kirkpatrick,

and KathrynShevelow.

Joseph Joachim,Briefe von und an JosephJoachim, ed. Johannes Joachimand

Andreas Moser, 3 vols. (Berlin: Julius Bard, 1911-13), 2:86; cited in Nancy B. Reich,

Clara Schumann: The Artistand the Woman (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell UniversityPress,

1985), 320; the translationis Reich's. See the chapter entitled "Clara Schumann as

Composer and Editor," 225-57.

[Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1988, vol. 13, no. 3]

?1988 by The Universityof Chicago. All rightsreserved. 0097-9740/88/1303-0011$01.00

454

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

the reasons she could notbe a moreproductivecomposeris that

she was keptbusywiththeeightchildrenshe and RobertSchumann

producedtogether.

Fromourvantagepoint,we recognizeclaimsthat"thereare no

greatwomen artists"as expressionsof a gender-basedparadigm

concerningthe dispositionofpowerin the familyand the state.As

feministresearchfroma varietyof disciplineshas shown,the op-

positionbetweenproductiveand reproductive workorganizesthe

waya culturevalues work:thisparadigmdepictsoriginality orcrea-

tivityin termsof paternityand authority, relegatingthe figureof

the femaleto a varietyof secondaryroles. I am interestedin this

oppositionspecifically as itis used to markthedistinction between

writingand translating-marking, thatis, theone to be originaland

"masculine,"the otherto be derivativeand "feminine."The dis-

tinctionis onlysuperficially a problemofaesthetics,forthereare

important consequences in the areas of publishing,royalties,cur-

riculum,and academic tenure.WhatI proposehere is to examine

whatis at stakeforgenderin the representation oftranslation:the

struggleforauthority and the politicsoforiginality informing this

struggle.

"At best an echo,"2translationhas been figuredliterallyand

metaphorically in secondaryterms.Justas Clara Schumann'sper-

formanceofa musicalcompositionis seen as qualitativelydifferent

fromtheoriginalactofcomposingthatpiece, so theactoftranslating

is viewed as somethingqualitativelydifferent fromthe originalact

of writing.Indeed, under currentAmericancopyrightlaw, both

translations and musicalperformances are treatedunderthe same

rubricof"derivativeworks."3 The culturalelaborationofthisview

suggeststhatin the originalabides what is natural,truthful, and

lawful,in the copy,whatis artificial, false,and treasonous.Trans-

lationscan be, forexample,echoes (in musical terms),copies or

portraits(in painterlyterms),or borrowedor ill-fitting clothing(in

sartorialterms).

The sexualizationoftranslation appearsperhapsmostfamiliarly

in the tag les belles infideles-likewomen,the adage goes, trans-

lationsshouldbe eitherbeautifulor faithful. The tag is made pos-

sible bothby the rhymein Frenchand by the factthatthe word

traductionis a feminineone, thusmakingles beaux infidelesim-

possible. This tag owes its longevity-itwas coined in the seven-

2This is the title of an essay by Armando S. Pires, Americas 4, no. 9 (1952):

13-15, cited in On Translation, ed. Reuben A. Brower (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

UniversityPress, 1959), 289.

3United States Code Annotated,Title 17, Sect. 101 (St. Paul, Minn.: West Pub-

lishing Co., 1977).

455

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

teenthcentury4-tomorethanphoneticsimilarity: whatgivesitthe

appearance of truthis thatit has captureda culturalcomplicity

between the issues of fidelityin translationand in marriage.For

les belles infideles,fidelityis definedby an implicitcontractbe-

tween translation(as woman)and original(as husband,father,or

author).However,the infamous"double standard"operateshere

as it mighthave in traditionalmarriages:the "unfaithful"wife/

translationis publiclytriedforcrimesthe husband/original is by

law incapable of committing. This contract,in short,makes it im-

possible forthe originalto be guiltyofinfidelity. Such an attitude

betraysreal anxietyabouttheproblemofpaternity and translation;

it mimicsthe patrilinealkinshipsystemwherepaternity-notma-

ternity-legitimizes an offspring.

It is the strugglefortherightofpaternity, regulatingthe fidelity

oftranslation, whichwe see articulatedby the earl ofRoscommon

in his seventeenth-century In orderto guar-

treatiseon translation.

antee the originality ofthe translator'swork,surelynecessaryin a

paternity case, thetranslatormustusurptheauthor'srole. Roscom-

monbeginsbenignlyenough,advisingthe translator to "Chuse an

authoras you chuse a friend," butthisintimacyservesa potentially

subversivepurpose:

Unitedby thisSympathetick Bond,

You growFamiliar,Intimate,and Fond;

Yourthoughts, yourWords,yourStiles,yourSouls agree,

but He.5

No longerhis Interpreter,

It is an almostsilentdeposition:throughfamiliarity (friendship),

thetranslator becomes,as itwere,partofthefamilyand finallythe

fatherhimself;whateverstruggletheremightbe between author

and translator is veiled by the language of friendship.While the

translator is figuredas a male, the textitselfis figuredas a female

whose chastitymustbe protected:

Withhow muchease is a youngMuse Betray'd

How nice the Reputationofthe Maid!

Yourearly,kind,paternalcare appears,

By chastInstruction ofherTenderYears.

The firstImpressionin her InfantBreast

Will be the deepest and shouldbe the best.

4Roger Zuber, Les "Belles Infideles" et la formation du gout classique (Paris:

Librairie Armand Colin, 1968), 195.

5Earl of Roscommon, "An Essay on Translated Verse," in English Translation

Theory-1650-1800, ed. T. R. Steiner (Amsterdam:Van Gorcum, Assen, 1975), 77.

456

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

Let no Austerity

breed servileFear

No wantonSound offendherVirginEar.6

As the translatorbecomes the author,he incurscertainpaternal

duties in relationto the text,to protectand instruct-orperhaps

structure-it.The languageused echoes the language of conduct

books and reflectsattitudesabout the properdifferencesin edu-

catingmales and females;"chastInstruction"is properforthe fe-

male,whose virginity is an essentialprerequisiteto marriage.The

text,that blank page bearingtheauthor'simprint ("The first

Impres-

sion . . . Will be thedeepest"),is impossiblytwicevirgin-once for

the originalauthor,and again forthe translator who has takenhis

place. It is this"chastity" which resolves-or represses-the strug-

gle forpaternity.7

The genderingoftranslation by thislanguageofpaternalismis

made moreexplicitin theeighteenth-century treatiseon translation

by Thomas Francklin:

Unless an authorlike a mistresswarms,

How shall we hide his faultsor tastehis charms,

How all his modestlatentbeauties find,

How traceeach lovelierfeatureofthe mind,

Softeneach blemish,and each graceimprove,

And treathimwiththe dignityofLove?8

Like the earl ofRoscommon,Francklinrepresentsthetranslator as

a male who usurpsthe role oftheauthor,a usurpationwhichtakes

place at the level ofgrammatical genderand is resolvedthrougha

sex change.The translator is figuredas a male seducer;the author,

conflatedwiththe conventionally "feminine"featuresof his text,

is thenthe "mistress," and themasculinepronounis forcedto refer

to thefeminineattributes ofthetext("his modestlatentbeauties").

In confusingthe genderofthe authorwiththe ascribedgenderof

the text,Francklin"translates"the creativerole ofthe authorinto

the passive role of the text,renderingthe authorrelativelypow-

erless in relationto the translator.The author-text,now a mistress,

is flatteredand seduced by the translator's attentions,becominga

6Ibid., 78.

70n the woman as blank page, see Susan Gubar, "'The Blank Page' and Issues

of Female Creativity,"in Writingand Sexual Difference, ed. Elizabeth Abel (Chi-

cago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 73-94; see also Stephanie Jed, Chaste

Thinking: The Rape of Lucretia and the Birth of Humanism (Bloomington: Indiana

UniversityPress, in press).

8Thomas Francklin, "Translation: A Poem," in Steiner, ed., 113-14.

457

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

willing collaborator in the project to make herself beautiful-and,

no doubt, unfaithful.

This belle infidele, whose blemishes have been softened and

whose beauties have thereforebeen improved, is depicted both as

mistress and as a portraitmodel. In using the popular painting

analogy, Francklin also reveals the gender coding of that mimetic

convention: the translator/painter must seduce the text in order to

"trace" (translate) the features of his subject. We see a more elab-

orate version of this convention, though one arguing a different

position on the subject of improvementthroughtranslation,in Wil-

liam Cowper's "Preface" to Homer's Iliad: "Should a painter,pro-

fessing to draw the likeness of a beautiful woman, give her more

or fewer featuresthan belong to her, and a general cast of counte-

nance of his own invention, he might be said to have produced a

jeu d'esprit, a curiosity perhaps in its way, but by no means the

lady in question."9 Cowper argues forfidelityto the beautifulmodel,

lest the translationdemean her, reducing her to a mere "jeu d'es-

prit," or, to follow the text yet further,make her monstrous ("give

her more or fewer features"). Yet lurkingbehind the phrase "the

lady in question" is the suggestion that she is the other woman-

the beautiful, and potentiallyunfaithful,mistress.In any case, like

the earl of Roscommon and Francklin, Cowper feminizes the text

and makes her reputation-that is, her fidelity-the responsibility

of the male translator/author.

Justas textsare conventionally figuredin feminineterms,so too

is language: our "mother tongue." And when aesthetic debates

shifted the focus in the late eighteenth centuryfromproblems of

mimesis to those of expression-in Abrams's famous terms, from

the mirrorto the lamp-discussions oftranslationfollowed suit. The

translator'srelationship to this motherfigureis outlined in some of

the same terms that we have already seen-fidelity and chastity-

and the fundamental problem remains the same: how to regulate

legitimate sexual (authorial) relationships and their progeny.

A representative example depicting translationas a problem of

fidelityto the "mother tongue" occurs in the work of Schleier-

macher,whose twin interestsin translationand hermeneutics have

been influential in shaping translationtheory in this century.In

discussing the issue of maintaining the essential foreignness of a

text in translation,Schleiermacher outlines what is at stake as fol-

lows: "Who would not like to permit his mother tongue to stand

fortheverywhere in the most universally appealing beauty each

genre is capable of? Who would not rathersire children who are

9William Cowper, "'Preface' to The Iliad of Homer," in Steiner, ed., 135-36.

458

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

theirparents'pure effigy, and notbastards?.. . Who would suffer

being accused, like those parentswho abandon theirchildrento

acrobats,of bendinghis mothertongueto foreignand unnatural

dislocationsinstead of skillfullyexercisingit in its own natural

gymnastics?"'? The translator,as father,

mustbe trueto themother/

language in orderto producelegitimateoffspring; ifhe attemptsto

sire children otherwise, he will produce bastardsfitonly forthe

of

circus.Because the mothertongueis conceived as natural,any

tamperingwith it-any infidelity-isseen as unnatural,impure,

monstrous, and immoral.Thus, it is "natural"law whichrequires

monogamousrelationsin orderto maintainthe "beauty" of the

languageand in orderto insurethatthe worksbe genuineor orig-

inal. Thoughhis referenceto bastardchildrenmakesclear thathe

is concernedoverthe purityofthe mothertongue,he is also con-

cernedwiththe paternity ofthe text."Legitimacy"has littleto do

withmotherhoodand moreto do withthe institutional acknowl-

edgmentoffatherhood. The question,"Whois therealfatherofthe

text?"seems to motivatethese concernsabout boththe fidelityof

the translation and the purityofthe language.

In themetaphorics oftranslation,thestruggleforauthorialrights

takesplace bothin the realmof the family, as we have seen, and

in the state,fortranslationhas also been figuredas the literary

equivalentofcolonization,a meansofenrichingboththelanguage

and the literatureappropriateto the politicalneeds of expanding

nations.A typicaltranslator's prefacefromthe Englisheighteenth

centurymakesthisexplicit:"You, myLord,knowhow the works

ofgeniusliftup thehead ofa nationabove herneighbors,and give

as much honoras success in arms;amongthese we mustreckon

ourtranslations oftheclassics;by whichwhenwe havenaturalized

all Greece and Rome,we shall be so muchricherthantheyby so

manyoriginalproductions as we haveofourown."1 Because literary

is

success equated with militarysuccess, translationcan expand

both literaryand politicalborders.A similarattitudetowardthe

enterpriseof translation maybe foundin the GermanRomantics,

whoused ubersetzen(totranslate) and verdeutschen(toGermanize)

interchangeably: translationwas literallya strategyof linguistic

incorporation. The greatmodelforthisuse oftranslation is,ofcourse,

theRomanEmpire,whichso dramatically incorporated Greekcul-

'lFriedrich Schleiermacher, "Uber die verschiedenen Methoden des Ueber-

setzen," trans. Andre Lefevere, in Translating Literature: The German Tradition

from Luther to Rosenzweig, ed. Andre Lefevere (Amsterdam:Van Gorcum, Assen,

1977), 79.

"Cited in Flora Ross Amos, Early Theories of Translation (1920; reprint,New

York: Octagon Books, 1973), 138-39.

459

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

tureintoits own. For the Romans,Nietzscheasserts,"translation

was a formofconquest."12

Then, too,the politicsofcolonialismoverlapsignificantly

with

the politicsof genderwe have seen so far.Flora Amos shows,for

example,thatduringthe sixteenthcenturyin England,translation

is seen as "public duty."The most stunningexample of what is

construedas "public duty" is articulatedby a sixteenth-century

English translatorof Horace named Thomas Drant,who, in the

prefaceto his translation

ofthe Romanauthor,boldlyannounces,

FirstI havenowdone as thepeople ofGod werecommanded

to do with theircaptive women thatwere handsome and

beautiful:I have shavedoffhis hairand pared offhis nails,

thatis, I have wiped away all his vanityand superfluity

of

matter... I have Englishedthingsnotaccordingto thevein

of the Latin propriety,but of his own vulgar tongue. ... I

have pieced his reason,eked and mended his similitudes,

mollifiedhis hardness,prolongedhis cortallkindofspeeches,

changedand muchalteredhis words,but not his sentence,

or at least (I dare say) nothis purpose.13

Drantis freeto takethe libertieshe here describes,for,as a cler-

gymantranslating a secularauthor,he mustmake Horace morally

suitable:he musttransform himfromthe foreignor alien into,sig-

a

nificantly, member of the family.For the passage fromthe Bible

to whichDrantalludes (Deut. 21:12-14) concernsthe properway

to make a captivewomana wife:"Then you shall bringher home

to yourhouse; and she shall shave her head and pare her nails"

(Deut. 21:12, Revised StandardVersion).Aftergivingher a month

in whichto mourn,thecaptorcan thentakeheras a wife;butifhe

findsin herno "delight,"the passage forbidshimsubsequentlyto

sell herbecause he has alreadyhumiliatedher.In makingHorace

suitableto becomea wife,Drantmusttransform himintoa woman,

the uneasy effectsof which remainin the tensionof pronominal

reference,where "his" seems to referto "women." In addition,

Drant'sparaphrasemakesit the husband-translator's dutyto shave

and pare ratherthanthedutyofthecaptiveHorace. Unfortunately,

captorsoftendid muchmorethanshavetheheads ofcaptivewomen

(see Num. 31:17-18); the sexual violence alluded to in this de-

scriptionof translationprovidesan analogue to the politicaland

economicrapes implicitin a colonializingmetaphor.

'2Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. Walter Kauffmann(New York:

Random House, 1974), 90.

'3Cited in Amos, 112-13.

460

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

Clearly,the meaningof the word "fidelity"in the contextof

translation changesaccordingto the purposetranslation is seen to

servein a largeraestheticor culturalcontext.In its genderedver-

sion,fidelitysometimesdefinesthe (female)translation's relation

to the original,particularlyto the original'sauthor(male),deposed

and replaced by the author(male) of the translation. In thiscase,

thetext,ifit is a good and beautifulone, mustbe regulatedagainst

its propensityforinfidelity in orderto authorizethe originality of

this production.Or, fidelitymightalso define a (male) author-

translator's relationto his (female) mothertongue,the language

intowhichsomethingis beingtranslated.In thiscase, the(female)

languagemustbe protectedagainstvilification. It is, paradoxically,

thissortof fidelitythatcan justifythe rape and pillage of another

languageand text,as we have seen in Drant.But again,thissortof

fidelityis designedto enrichthe "host"languageby certifying the

originalityof translation;the conquests,made captive,are incor-

poratedintothe "worksofgenius" ofa particularlanguage.

It shouldby now be obviousthatthismetaphorics oftranslation

revealsbothan anxietyaboutthemythsofpaternity (or authorship

and authority) and a profoundambivalenceabout the role of ma-

ternity-ranging fromthe condemnationof les belles infidelesto

the adulationaccordedto the "mothertongue."In one ofthe few

attempts todeal withboththepracticeand themetaphorics oftrans-

lation,Serge Gavronsky argues that the source of this anxietyand

ambivalencelies in the oedipal structure whichinforms the trans-

lator'soptions.Gavronskydivides the world of translationmeta-

phorsintotwocamps.The first grouphe labels pietistic:metaphors

based on thecoincidenceofcourtly and Christian traditions, wherein

the conventionalknightpledges fidelityto the unravishedlady,as

the Christianto theVirgin.In thiscase, thetranslator (as knightor

Christian)takesvows ofhumility, poverty-andchastity. In secular

terms,this is called "positional"translation, forit depends on a

well-known hierarchizationoftheparticipants. The verticalrelation

(author/translator)has thusbeen overlaidwithbothmetaphysical

and ethicalimplications,and in thismissionaryposition,submis-

sivenessis nextto godliness.

Gavronsky arguesthatthe master/slave schemaunderlyingthis

metaphoric model oftranslation is preciselythe foundationofthe

oedipal triangle:

Here, in typicallyeuphemisticterms,the slave is a willing

one (a hyperbolicservant,a faithful):

thetranslatorconsiders

himselfas the child ofthefather-creator,

his rival,while the

textbecomes the objectofdesire,thatwhichhas been com-

461

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

pletelydefinedby the paternalfigure,the phallus-pen.Tra-

ditions(taboos)imposeuponthetranslator a highlyrestricted

ritualrole. He is forcedto curtailhimself(strictlyspeaking)

in ordertorespecttheinterdictions on incest.To tamperwith

thetextwouldtotantamount to eliminating,in partortotally,

the dominantpresent.14

the father-author(ity),

Thus, the "paternalcare" ofwhichthe earl ofRoscommonspeaks

is one manifestation ofthisrepressedincestuousrelationwiththe

text,a second being the concernforthe purityof "mother"(ma-

donna) tongues.

The otherside of the oedipal trianglemaybe seen in a desire

to killthe symbolicfathertext/author. Accordingto Gavronsky, the

alternative tothepietistictranslatoris thecannibalistic, "aggressive

translator who seizes possession of the 'original,'who savorsthe

text,thatis,whotrulyfeedsuponthewords,whoingurgitates them,

and who, thereafter, enunciatesthemin his own tongue,thereby

havingexplicitlyridhimselfofthe'original'creator."5 Whereasthe

"pietistic"modelrepresentstranslators as completelysecondaryto

what is pure and original,the "cannibalistic"model, Gavronsky

claims,liberatestranslators fromservility to "culturaland ideolog-

ical restrictions." WhatGavronskydesires is to freethe translator/

translation fromthe signsofculturalsecondariness,but his model

is unfortunately inscribedwithinthe same set ofbinarytermsand

either/or logic that we have seen in the metaphoricsoftranslation.

Indeed, we can see theextentto whichGavronsky's metaphorsare

still inscribedwithinthatideologyin the followingdescription:

"The originalhas been captured,raped,and incestperformed. Here,

once again,the son is fatherofthe man.The originalis mutilated

beyond recognition;the slave-master dialectic reversed."16 In re-

peatingthe sortofviolence we have already seen so remarkably in

Drant,Gavronsky of

betraysthedynamics power in this"paternal"

system.Whetherthetranslator quietlyusurpstheroleoftheauthor,

thewaytheearlofRoscommonadvocates,ortakesauthority through

moreviolentmeans,power is stillfiguredas a male privilegeex-

ercisedin familyand statepoliticalarenas.The translator, forGav-

ronsky, is a male who repeatson the sexual level the kinds ofcrimes

any colonizingcountry commits on its colonies.

As Gavronsky himselfacknowledges,thecannibalistictranslator

is based on the hermeneuticist model ofGeorge Steiner,the most

14Serge Gavronsky,"The Translator: From Piety to Cannibalism," Sub-stance

16 (1977): 53-62, esp. 55.

15Ibid., 60.

16Ibid.

462

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

prominent contemporary theorist oftranslation;Steiner'sinfluential

model illustratesthe persistenceofwhatI have called the politics

of originalityand its logic ofviolence in contemporary translation

theory. In his After Babel, Steiner a

proposes four-part process of

translation.The firststep,thatof "initiativetrust,"describes the

translator'swillingnessto take a gamble on the text,trustingthat

thetextwill yield something. As a second step,thetranslator takes

an overtlyaggressivestep,"penetrating"and "capturing"the text

(Steinercalls this "appropriativepenetration"),an act explicitly

comparedto eroticpossession. Duringthe thirdstep,the impris-

onedtextmustbe "naturalized," mustbecomepartofthetranslator's

language,literallyincorporated or embodied. Finally,to compen-

sate forthis "appropriative'rapture,'"the translator mustrestore

thebalance,attemptsomeactofreciprocity to makeamendsforthe

act of aggression.His model forthisact of restitution is, he says,

"thatofLevi-Strauss's Anthropologie structurale which regardsso-

cial structuresas attemptsatdynamicequilibriumachievedthrough

an exchangeofwords,women,and materialgoods."Steinerthereby

makestheconnectionexplicitbetweentheexchangeofwomen,for

example,and the exchangeofwordsin one languageforwordsin

another.'7

Steinermakesthe sexual politicsofhis argumentquite clear in

the openingchapterofhis book,wherehe outlinesthe model for

"totalreading."Translation, as an act ofinterpretation,is a special

case of communication, and communication is a sexual act: "Eros

and languagemeshat everypoint.Intercourseand discourse,cop-

ula and copulation,are sub-classesof the dominantfactof com-

munication.... Sex is a profoundly semanticact."18Steinermakes

note of a culturaltendencyto see thisact of communication from

themale pointofviewand thustovalorizethepositionofthefather/

author/original, but at the same time,he himselfrepeatsthismale

focusin, forexample,the followingdescriptionofthe relationbe-

tween sexual intercourseand communication: "There is evidence

thatthe sexual dischargein male onanismis greaterthan it is in

intercourse. I suspectthatthe determining factoris articulateness,

theabilitytoconceptualizewithespecial vividness.... Ejaculation

is at once a physiologicaland a linguisticconcept.Impotenceand

speech-blocks, premature emissionand stuttering, involuntary ejac-

ulationand the word-river ofdreamsare phenomenawhose inter-

relationsseem to lead back to the centralknotof our humanity.

Semen,excreta,and wordsare communicative products."'9 The al-

17George Steiner, After Babel (London: Oxford University Press, 1975), 296,

298, 300, 302.

18Ibid., 38.

9Ibid., 44, 39.

463

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

lusion here to Levi-Strauss, echoed later in the book in the passage

we have already noted ("an exchange ofwords,women, and material

goods"), provides the narrativeconnecting discourse, intercourse,

and translation,and it does so fromthe point of view of a male

translator.Indeed, we note that when communication is at issue,

that which can be exchanged is depicted at least partially in male

terms ("semen, excreta, and words"), while when "restitution" is

at issue, thatwhich can be exchanged is depicted in female terms.

Writingwithin the hierarchyof gender, Steiner seems to argue

furtherthatthe paradigm is universal and thatthe male and female

roles he describes are essential ratherthan accidental. On the other

hand, he notes that the rules for discourse (and, presumably, for

intercourse) are social, and he outlines some of the consequent

differencesbetween male and female language use:

At a rough guess, women's speech is richer than men's in

those shadings of desire and futurityknown in Greek and

Sanskritas optative; women seem to verbalize a wider range

of qualified resolve and masked promise. ... I do not say

they lie about the obtuse, resistantfabric of the world: they

multiply the facets of reality,they strengthenthe adjective

to allow it an alternativenominal status,in a way which men

often find unnerving. There is a strain of ultimatum,a sep-

aratiststance, in the masculine intonationof the first-person

pronoun; the "I" of women intimatesa more patient bearing,

or did until Women's Liberation. The two language models

follow on Robert Graves's dictum that men do but women

are.20

But, while acknowledging the social and economic forces which

prescribe differences,he wants to believe as well in a basic bio-

logical cause: "Certain linguistic differences do point towards a

physiological basis or, to be exact, towards the intermediaryzone

between the biological and the social."21 Steiner is careful not to

insist on the biological premises, but there is in his own rhetorica

tendency to treateven the socialized differencesbetween male and

female language use as immutable. If the sexual basis of commu-

nication as the basis for translationis to be taken as a universal,

then Steiner would seem to be arguing firmlyin the traditionwe

have here been examining, one in which "men do" but "women

are." This traditionis not, of course, confined to the area of trans-

lation studies, and, given the influence of both Steiner and Levi-

20Ibid., 41.

21

Ibid., 43.

464

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

Strauss,it is notsurprising

to see genderas the framing

conceptof

communicationin adjacent fields such as semioticsor literary

criticism.22

The metaphorics oftranslation,as theprecedingdiscussionsug-

is a

gests, symptom largerof issues ofwesternculture:ofthepower

relationsas theydivide in termsofgender;ofa persistent(though

notalwayshegemonic)desire to equate languageor languageuse

withmorality;ofa quest fororiginality or unity,and a consequent

intoleranceof duplicity,of what cannotbe decided. The funda-

mentalquestion is, why have the two realms of translationand

genderbeen metaphorically linked?What,in Eco's terms,is the

metonymic code or narrativeunderlyingthese two realms?23

This surveyofthe metaphorsoftranslation would suggestthat

the implied narrativeconcernsthe relationbetween the value of

productionversusthe value ofreproduction. Whatproclaimsitself

to be an aestheticproblemis representedin termsof sex, family,

and the state,and whatis consistently at issue is power.We have

already seen the way the of

concept fidelity is used to regulatesex

and/inthe family, to guaranteethatthe child is the productionof

the father, reproducedby the mother.This regulationis a sign of

the father'sauthority and power; it is a way ofmakingvisible the

paternity of the child-otherwise a fictionof sorts-and thereby

claiming the child as legitimate progeny.It is also,therefore, related

to the owningand bequeathal of property. As in marriage,so in

translation, thereis a legal dimensionto the conceptoffidelity. It

is notlegal (shall I say,legitimate)to publisha translation ofworks

not in the public domain,forexample,withoutthe author's(or

appropriateproxy's)consent;one must,in short,enterthe proper

contractbeforeannouncingthebirthofthe translation, so thatthe

parentage will be clear. The of and

coding production reproduction

marksthe formeras a morevaluable activityby referenceto the

divisionoflaborestablishedforthe marketplace, whichprivileges

maleactivity and paysaccordingly. The transformation oftranslation

froma reproductive activityintoa productiveone,froma secondary

workintoan originalwork,indicatesthecodingoftranslation rights

as property rights-signsofriches,signsofpower.

22In her incisive

critique ofsemiotics argued along these lines, Christine Brooke-

Rose makes a similar point about Steiner's use of Levi-Strauss; see "Woman as

Semiotic Object," Poetics Today 6, nos. 1-2 (1985): 9-20; reprintedin The Female

Body in WesternCulture: Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Susan Rubin Suleiman

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UniversityPress, 1986), 305-16.

23 Umberto Eco, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics

of Texts

(Bloomington: Indiana UniversityPress, 1979), 68.

465

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

I would furtherargue thatthe reason translationis so overcoded,

so overregulated,is thatit threatensto erase the differencebetween

productionand reproductionwhich is essential to the establishment

of power. Translationscan, in short,masquerade as originals,thereby

short-circuiting the system.That the differenceis essential to main-

tain is argued in terms of life and death: "Every saddened reader

knows that what a poem is most in danger of losing in translation

is its life."24The danger posed by infidelityis here represented in

terms of mortality;in a comment on the Loeb Library translations

ofthe classics, Rolfe Humphries articulatesthe riskin more specific

terms:"They emasculate theiroriginals."25The sexual violence im-

plicit in Drant's figurationof translation,then, can be seen as di-

rected not simply against the female material of the text ("captive

women") but against the sign of male authorityas well; for,as we

know fromthe storyof Samson and Delilah, Drant's cuttingof hair

("I have shaved offhis hair and pared offhis nails, that is, I have

wiped away all his vanity and superfluityof matter") can signify

loss of male power, a symbolic castration.This, then, is what one

criticcalls the manque inevitable: what the original risks losing, in

short,is its phallus, the sign ofpaternity,authority,and originality.26

* * *

In the metaphoric system examined here, what the translator

claims for"himself" is precisely the rightof paternity;he claims a

phallus because this is the only way, in a patriarchalcode, to claim

legitimacyforthe text.To claim thattranslatingis like writing,then,

is to make it a creative-rather than merely re-creative-activity.

But the claims for originalityand authority,made in reference to

acts of artisticand biological creation, exist in sharp contrastto the

place of translationin a literaryor economic hierarchy.For, while

writing and translatingmay share the same figuresof gender di-

vision and power-a concern with the rightsof authorship or au-

thority-translatingdoes not share the redemptive mythsof nobility

or triumph we associate with writing. Thus, despite metaphoric

claims for equality with writers, translatorsare often reviled or

ignored: it is not uncommon to find a review of a translationin a

24JacksonMatthews, "Third Thoughts on Translating Poetry,"in Brower,ed. (n.

2 above), 69.

25Rolfe Humphries, "Latin and English Verse-Some Practical Considerations,"

in Brower, ed., 65.

2Philip Lewis, "Vers la traductionabusive," in Les fins de l'homme: A partir

du travail de Jacques Derrida, ed. Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy

(Paris: Editions Galilee, 1981), 253-61, esp. 255.

466

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

majorperiodicalthatfailsto mentionthe translator or the process

oftranslation. Translationprojectsin today'suniversitiesare gen-

erallyconsideredonlymarginally appropriateas topicsfordoctoral

dissertationsor as supportfortenure,unless the originalauthor's

statureis sufficient to authorizethe project.While organizations

suchas PEN and ALTA(AmericanLiteraryTranslators Association)

are workingto improvethetranslator's economicstatus,organizing

translators and advisingthemoftheirlegal rightsand responsibil-

ities,even thebest translators are stillpoorlypaid. The academy's

general scorn fortranslationcontrasts sharplywithits relianceon

translation in thestudyofthe"classics" ofworldliterature, ofmajor

philosophical and critical

texts, and of previouslyunread master-

pieces ofthe "third"world.While the metaphorswe have looked

atattempt tocloakthesecondarystatusoftranslation inthelanguage

ofthe phallus,westerncultureenforcesthissecondarinesswitha

vengeance,insistingon the feminizedstatusof translation. Thus,

thoughobviouslybothmen and womenengage in translation, the

binarylogic which encouragesus to definenursesas femaleand

doctorsas male,teachersas femaleand professorsas male, secre-

tariesas femaleand corporateexecutivesas male also definestrans-

lationas, in manyways,an archetypalfeminineactivity.

Whatis also interesting is that,even when the termsof com-

parisonare reversed-whenwritingis said to be like translating-

in ordertostressthere-creative aspectsofbothactivities, thegender

bias does not disappear.For example,in a shortessay by Terry

Eagleton discussingthe relationbetween translationand some

strandsofcurrentcriticaltheory, Eagletonarguesas follows:

It maybe, then,thattranslation fromone languageintoan-

othermaylay bare forus somethingof the veryproductive

mechanismsoftextuality itself... The eccentricyetsugges-

tivecriticaltheoriesofHaroldBloom ... contendthatevery

poeticproduceris locked in Oedipal rivalrywitha "strong"

patriarchal precursor-thatliterary "creation"... is in reality

a matterofstruggle, anxiety,aggression,envyand repression.

The "creator"cannotabolishtheunwelcomefactthat. . his

poem lurksin the shadows of a previouspoem or poetic

tradition,againstthe authority of whichit mustlabourinto

itsown"autonomy." On Bloom'sreading,all poemsaretrans-

lations,or "creativemisreadings," ofothers;and itis perhaps

onlytheliteraltranslatorwhoknowsmostkeenlythepsychic

cost and enthrallment whichall writinginvolves.27

27TerryEagleton, "Translation and Transformation,"Stand 19, no. 3 (1977):

72-77, esp. 73-74.

467

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

Eagleton's point, throughBloom, is thatthe productive or creative

mechanism of writingis not original, that is, texts do not emerge

ex nihilo; rather,both writingand translatingdepend on previous

texts. Reversing the conventional hierarchy,he invokes the sec-

ondary status of translation as a model for writing. In equating

translationand "misreading," however, Eagleton (throughBloom)

"

findstheircommon denominatorto be the strugglewith a 'strong'

patriarchal precursor"; the productive or creative mechanism is,

again, entirely male. The attemptby either Eagleton or Bloom to

replace the concept of originalitywith the concept of creative mis-

reading or translationis a sleight of hand, a change in name only

with respect to gender and the metaphorics of translation,forthe

concept oftranslationhas here been defined in the same patriarchal

terms we have seen used to define originalityand production.

At the same time, however, much of recent critical theory has

called into question the mythsof authorityand originalitywhich

engender this privilegingofwritingover translatingand make writ-

ing a male activity.Theories of intertextuality, for example, make

it difficultto determine the precise boundaries of a text and, as a

consequence, disperse the notion of "origins"; no longer simply

the product of an autonomous (male?) individual, the text rather

findsits sources in history,that is, within social and literarycodes,

as articulated by an author. Feminist scholarship has drawn atten-

tion to the considerable body of writingby women, writing pre-

viously marginalized or repressed in the academic canon; thus this

scholarship brings to focus the conflictbetween theories of writing

coded in male terms and the reality of the female writer. Such

scholarship, in articulatingthe role gender has played in our con-

cepts of writingand production, forces us to reexamine the hier-

archies thathave subordinatedtranslationto a concept oforiginality.

The resultantrevisioningof translationhas consequences, of course,

formeaning-makingactivities of all kinds, fortranslationhas itself

served as a conventional metaphor or model fora varietyof acts of

reading, writing,and interpretation;indeed, the analogy between

translationand interpretationmightprofitablybe examined in terms

of gender,forits use in these discourses surelybelies similar issues

concerning authority,violence, and power.

The most influentialrevisionist theoryof translationis offered

by Jacques Derrida, whose project has been to subvert the very

concept of differencewhich produces the binary opposition be-

tween an original and its reproduction-and finallyto make this

difference undecidable. By drawing many of his terms fromthe

lexicon of sexual difference-dissemination, invagination,hymen-

Derrida exposes gender as a conceptual frameworkfordefinitions

of mimesis and fidelity,definitionscentral to the "classical" way of

468

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

viewingtranslation. The problemof translation, implicitin all of

his work,has become increasingly explicitsince his essay "Living

On /BorderLines," thepretextsforwhichare Shelley's "Triumph

ofLife" and Blanchot'sL'arretde mort.28 In suggestingthe "inter-

translatability"of thesetexts,he violates conventional attitudesnot

only toward translation,but also toward influence and authoring.

The essay is on translationin manysenses: appearingfirstin

English-that is, in translation-itcontainsa runningfootnoteon

the problemsof translating his own ambiguoustermsas well as

thoseof Shelley and Blanchot.In the process,he exposes the im-

possibilityof the "dream of translationwithoutremnants";there

is, he argues,always somethingleftover whichblursthe distinc-

tionsbetween originaland translation. There is no "silent" trans-

lation.For example,he notes the importanceof the words ecrit,

recit,and seriein Blanchot'stextand asks: "Note to thetranslators:

How are you going to translatethat,recit,forexample? Not as

nouvelle,'novella, noras 'shortstory.'Perhapsit will be betterto

leave the 'French' wordrecit.It is alreadyhardenoughto under-

stand,in Blanchot'stext,in French."29

The impossibility oftranslatinga wordsuchas recitis,according

to Derrida,a functionofthe law oftranslation, nota matterofthe

translation'sinfidelityor secondariness.Translationis governedby

a double bindtypified bythecommand,"Do notreadme": thetext

bothrequiresand forbidsitstranslation. Derridarefersto thisdou-

ble bind of translation as a hymen,the sign of bothvirginity and

consummation ofa marriage.Thus, in attempting to overthrow the

binaryoppositionswe have seen in otherdiscussionsofthe prob-

lem,Derridaimpliesthattranslation is bothoriginaland secondary,

uncontaminated and transgressed ortransgressive. Recognizingtoo

thatthetranslator is frequently

a woman-so thatsexand thegender-

ascribed secondarinessof the task frequentlycoincide-Derrida

goes on toarguein The Ear oftheOtherthat"thewomantranslator

in thiscase is notsimplysubordinated, she is notthe author'ssec-

retary.She is also theone who is loved bytheauthorand on whose

basis alone writingis possible. Translationis writing;thatis, it is

nottranslation onlyin the sense oftranscription. It is a productive

writingcalled forthby the originaltext."30 By arguingthe inter-

dependenceofwritingand translating, Derridasubvertstheauton-

28JacquesDerrida, "Living On /Border Lines," trans.James Hulbert, in Decon-

struction and Criticism, ed. Harold Bloom et al. (New York: Seabury Press, 1979),

75-176.

29Ibid., 119, 86.

30Ibid., 145; Jacques Derrida, The Ear

of the Other: Otobiography,Transference,

Translation, ed. Christie V. McDonald, trans. Peggy Kamuf (New York: Schocken

Books, 1985), 153.

469

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

omyand privilegeofthe"original"text,bindingittoan impossible

but necessarycontractwiththe translationand makingeach the

debtorofthe other.

In emphasizingboththereproductive and productiveaspectsof

translation,Derrida'sproject-and,ironically, thetranslation ofhis

works-provides a basis for a necessaryexploration of the contra-

dictionsoftranslation and gender.Alreadyhis workhas generated

a collectionof essays focusingon translationas a way of talking

about philosophy,interpretation, and literaryhistory.31 These es-

says, while notexplicitlyaddressingquestions gender,build on

of

his ideas about the doubleness oftranslation withouteitherideal-

or

izing subordinating translationto conventionallyprivilegedterms.

Derrida's own work,however,does not attendclosely to the his-

toricalorculturalcircumstances ofspecifictexts,circumstances that

cannotbe ignoredin investigating theproblematicsoftranslation.32

For example,in some historicalperiods women were allowed to

translatepreciselybecause it was definedas a secondaryactivity.33

Our taskas scholars,then,is to learn to listento the "silent" dis-

course-of women,as translators-inorderto betterarticulatethe

relationshipbetween whathas been coded as "authoritative" dis-

courseand whatis silenced in thefearofdisruption or subversion.

Beyondthiskindofscholarship,whatis requiredfora feminist

theoryof translationis a practicegovernedby what Derrida calls

the double bind-not the double standard.Such a theorymight

rely,noton thefamilymodelofoedipal struggle, buton thedouble-

edged razoroftranslation as collaboration,whereauthorand trans-

latorare seen as workingtogether, bothin the cooperativeand the

subversivesense. This is a model thatrespondsto the concerns

voiced by an increasinglyaudible numberof women translators

whoarebeginningtoask,as SuzanneJillLevinedoes,whatitmeans

to be a womantranslator in and ofa male tradition.Speakingspe-

cificallyof her recenttranslationof CabreraInfante'sLa Habana

31JosephF. Graham, ed., Difference in Translation (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Uni-

versityPress, 1985).

32 For a

critique of Derrida's "Living On /Border Lines" along these lines, see

Jeffrey Mehlman's essays, "Deconstruction, Literature,History:The Case ofL'Arret

de mort," in Literary History: Theory and Practice, ed. Herbert L. Sussman, Pro-

ceedings of the NortheasternUniversityCenter forLiteraryStudies (Boston, 1984),

and "Writingand Deference: The Politics of LiteraryAdulation," in Representations

15 (Summer 1986): 1-14.

33Margaret P. Hannay, ed., Silent But for the Word: Tudor Women as Patrons,

Translators, and Writers of Religious Works (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University

Press, 1985).

470

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1988 / SIGNS

para un infantedifunto,a textthat"mockswomenand theirwords,"

she asks, "Where does thisleave a womanas translator of such a

book? Is she nota double betrayer, to play Echo to thisNarcissus,

repeatingthearchetype once again?All who use themother'sfather-

tongue, who echo the ideas and discourseof greatmen are, in a

sense, betrayers: this is the contradiction and compromiseof dis-

sidence."34The verychoice of textsto workwith,then,poses an

initial dilemma forthe feministtranslator:while a textsuch as

CabreraInfante'smaybe ideologicallyoffensive, notto translateit

would capitulateto thatlogic whichascribesall powerto the orig-

inal. Levine chooses insteadto subvertthe text,to play infidelity

againstinfidelity, and to followout the text'sparodiclogic. Carol

in

Maier, discussingthe contradictions of her relationshipto the

Cuban poet OctavioArmand,makes a similarpoint,arguingthat

"the translator's quest is notto silence but to give voice, to make

availabletextsthatraise difficult questionsand open perspectives.

It is essentialthatas translators womenget underthe skinofboth

antagonisticand sympathetic works.They mustbecome indepen-

dent, 'resisting'interpreters who not only let antagonisticworks

speak ... butalso speak with them and place themina largercontext

bydiscussingthemand theprocessoftheirtranslation."35 Her essay

recountsher struggleto translatethe silencingof the motherin

Armand'spoetryand how,by "resisting"her own silencingas a

translator, she is able togivevoice tothecontradictions in Armand's

work.By refusingto repressherown voice while speakingfor the

voice ofthe"master," Maier,likeLevine,speaksthrough and against

translation. Bothofthesetranslators' workillustrates theimportance

notonlyoftranslating butofwritingaboutit,makingtheprinciples

of a practicepartof the dialogue about revisingtranslation.It is

onlywhenwomentranslators beginto discusstheirwork-andwhen

enoughhistoricalscholarshipon previouslysilencedwomentrans-

latorshas been done-that we will be able to delineatealternatives

to the oedipal strugglesforthe rightsofproduction.

For feminists workingon translation, muchor even mostofthe

terrainis stilluncharted. Wecan,forexample,examinethehistorical

role oftranslation in women'swritingin different periodsand cul-

tures;the special problemsoftranslating explicitlyfeministtexts,

as forexample,in MyriamDiaz-Diocaretz'sdiscussionoftheprob-

34Suzanne Jill Levine, "Translation as (Sub)Version: On Translating Infante's

Inferno," Sub-stance 42 (1984): 92.

35Carol Maier, "A Woman in Translation, Reflecting,"Translation Review, no.

17 (1985), 4-8, esp. 4.

471

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamberlain / TRANSLATION

lems oftranslating AdrienneRich intoSpanish;36the effectsofthe

canonand themarketplaceon decisionsconcerningwhichtextsare

translated, by whom,and how thesetranslations are marketed;the

effectsoftranslationson canonand genre;theroleof"silent"forms

of writingsuch as translationin articulating woman's speech and

subvertinghegemonic forms of expression.Feministand post-

structuralisttheory encouragedus to read between or outside

has

the lines ofthe dominantdiscourseforinformation about cultural

formation and authority;translationcan providea wealth of such

information about practicesof dominationand subversion.In ad-

dition,as both Levine's and Maier's commentsindicate,one ofthe

challenges forfeminist is to move beyondquestionsof

translators

the sex oftheauthorortranslator. Workingwithintheconventional

hierarchieswe have alreadyseen, the femaletranslator ofa female

author'stextand the male translator ofa male author'stextwill be

bound by the same powerrelations:whatmustbe subvertedis the

processby whichtranslation complieswithgenderconstructs.In

thissense,a feminist theory translation

of will finallybe utopic.As

women writetheirown metaphors of cultural production,it may

be possible to considerthe acts of authoring,creating,or legiti-

mizinga textoutsideofthegenderbinariesthathavemade women,

mistressesofthesortofworkthatkeptClara Schu-

like translations,

mannfromhercomposing.

Boalt Hall School of Law

of California,Berkeley

University

36Myriam Diaz-Diocaretz, Translating Poetic Discourse: Questions on Feminist

Strategies in Adrienne Rich (Amsterdam/Philadelphia:John Benjamins Publishing

Co., 1985). For otherworkthatbegins to address the specific problem of gender and

translation,see also the special issue ofTranslation Review on women in translation,

no. 17 (1985); and Ronald Christ,"The Translator'sVoice: An Interview with Helen

R. Lane," Translation Review, no. 5 (1980), 6-17.

472

This content downloaded from 62.122.73.229 on Tue, 10 Jun 2014 00:54:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- I Wandered Lonely As A Cloud Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesI Wandered Lonely As A Cloud Lesson PlanMinard A. Saladino80% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Una Hembra Argentina - Carlota Fainberg - Marta Ferrari - UNMDPDocument9 pagesUna Hembra Argentina - Carlota Fainberg - Marta Ferrari - UNMDPVictoria GiselleNo ratings yet

- Sabrina Riva - Identidades en ConflictoDocument36 pagesSabrina Riva - Identidades en ConflictoVictoria GiselleNo ratings yet

- La Razón Heroica de Juan Ramón Jiménez - Luis García MonteroDocument18 pagesLa Razón Heroica de Juan Ramón Jiménez - Luis García MonteroVictoria GiselleNo ratings yet

- Culler, J. - Poetics of The Lyric (In Structuralist Poetics)Document33 pagesCuller, J. - Poetics of The Lyric (In Structuralist Poetics)Victoria GiselleNo ratings yet

- Sarva Mangale Song Lyrics55 PDFDocument4 pagesSarva Mangale Song Lyrics55 PDFMalati KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Shaw George Bernard Dramatic Opinions and Essays Vol 1Document376 pagesShaw George Bernard Dramatic Opinions and Essays Vol 1Anonymous I78Rzn6rSNo ratings yet

- William ShakespeareDocument6 pagesWilliam ShakespeareRadu DascăluNo ratings yet

- Srila Prabhupada On 64 Rounds - 0Document4 pagesSrila Prabhupada On 64 Rounds - 0Anton ArsenNo ratings yet

- William SheakspearDocument4 pagesWilliam SheakspearMohamed AlhamdaniNo ratings yet

- Literature Through Time ReadingDocument8 pagesLiterature Through Time ReadingAnonymous NbKeZIGDVM50% (4)

- Modern African Literature and Cultural Identity: Tanure OjaideDocument3 pagesModern African Literature and Cultural Identity: Tanure OjaideHanisahNo ratings yet

- The Iliad and Odyssey CharactersDocument5 pagesThe Iliad and Odyssey CharactersJCNo ratings yet

- Harbinger of Grace and MercyDocument4 pagesHarbinger of Grace and Mercyliber(the poet);No ratings yet

- EN7LT-Ia-14.1: Identify The Distinguishing Features of Notable Anglo-American Lyric Poetry, Songs, Poems, and AllegoriesDocument6 pagesEN7LT-Ia-14.1: Identify The Distinguishing Features of Notable Anglo-American Lyric Poetry, Songs, Poems, and AllegoriesJayden EnzoNo ratings yet

- Buchta and Schweig Rasa Theory-Libre PDFDocument7 pagesBuchta and Schweig Rasa Theory-Libre PDFPeabyru PuitãNo ratings yet

- Magsino Acrostic PoemDocument1 pageMagsino Acrostic PoemLhiam Genesis S. Magsino3180927No ratings yet

- A Poison TreeDocument2 pagesA Poison TreeNORITA AHMADNo ratings yet

- Saptakoṭibuddhamātṛ Cundī Dhāraṇī SūtraDocument4 pagesSaptakoṭibuddhamātṛ Cundī Dhāraṇī SūtraZacGoNo ratings yet

- Modern English Literature Solved MCQs (Set-2)Document4 pagesModern English Literature Solved MCQs (Set-2)Gg ChNo ratings yet

- Klimenko & Stanyukovich 2018-Interference in Hudhud PDFDocument52 pagesKlimenko & Stanyukovich 2018-Interference in Hudhud PDFSergey KlimenkoNo ratings yet

- All Summer in A Day. Lesson - AnthologyDocument18 pagesAll Summer in A Day. Lesson - Anthologyrevert2007No ratings yet

- Hamel FadhilaDocument217 pagesHamel FadhilaAbdi ShukuruNo ratings yet

- Persuasive WritingDocument1 pagePersuasive Writingapi-260642329No ratings yet

- Essay 1 On RC Final DraftDocument7 pagesEssay 1 On RC Final DraftAnonymous dHzDvINo ratings yet

- Tpcastt Poetry AnalysisDocument4 pagesTpcastt Poetry Analysisapi-520867331No ratings yet

- Direct and Indirect SpeechDocument28 pagesDirect and Indirect SpeechAira PeloniaNo ratings yet

- Kenneth J. Dover ObituariesDocument7 pagesKenneth J. Dover ObituariesschediasmataNo ratings yet

- Highlights of English and American Literature: M. OchinangDocument77 pagesHighlights of English and American Literature: M. OchinangMelvin OchinangNo ratings yet

- Shahnama 08 FirduoftDocument472 pagesShahnama 08 FirduoftBranko VranešNo ratings yet

- Chapter-Wise Test Series: Class: IX Subject: EnglishDocument1 pageChapter-Wise Test Series: Class: IX Subject: EnglishBahawalpur 24/7No ratings yet

- Bernheimer OlympiaDocument24 pagesBernheimer OlympiaAlan JinsangNo ratings yet

- Taifas Literary Magazine No 12Document48 pagesTaifas Literary Magazine No 12Ioan MunteanNo ratings yet

- Lectures On Sanatana Dharma2Document42 pagesLectures On Sanatana Dharma2annsaralondeNo ratings yet